Abstract

Background: Health authorities are near universal in their recommendation to replace sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) with water. Non-nutritive sweetened beverages (NSBs) are not as widely recommended as a replacement strategy due to a lack of established benefits and concerns they may induce glucose intolerance through changes in the gut microbiome. The STOP Sugars NOW trial aims to assess the effect of the substitution of NSBs (the “intended substitution”) versus water (the “standard of care substitution”) for SSBs on glucose tolerance and microbiota diversity. Design and Methods: The STOP Sugars NOW trial (NCT03543644) is a pragmatic, “head-to-head”, open-label, crossover, randomized controlled trial conducted in an outpatient setting. Participants were overweight or obese adults with a high waist circumference who regularly consumed ≥1 SSBs daily. Each participant completed three 4-week treatment phases (usual SSBs, matched NSBs, or water) in random order, which were separated by ≥4-week washout. Blocked randomization was performed centrally by computer with allocation concealment. Outcome assessment was blinded; however, blinding of participants and trial personnel was not possible. The two primary outcomes are oral glucose tolerance (incremental area under the curve) and gut microbiota beta-diversity (weighted UniFrac distance). Secondary outcomes include related markers of adiposity and glucose and insulin regulation. Adherence was assessed by objective biomarkers of added sugars and non-nutritive sweeteners and self-report intake. A subset of participants was included in an Ectopic Fat sub-study in which the primary outcome is intrahepatocellular lipid (IHCL) by 1H-MRS. Analyses will be according to the intention to treat principle. Baseline results: Recruitment began on 1 June 2018, and the last participant completed the trial on 15 October 2020. We screened 1086 participants, of whom 80 were enrolled and randomized in the main trial and 32 of these were enrolled and randomized in the Ectopic Fat sub-study. The participants were predominantly middle-aged (mean age 41.8 ± SD 13.0 y) and had obesity (BMI of 33.7 ± 6.8 kg/m2) with a near equal ratio of female: male (51%:49%). The average baseline SSB intake was 1.9 servings/day. SSBs were replaced with matched NSB brands, sweetened with either a blend of aspartame and acesulfame-potassium (95%) or sucralose (5%). Conclusions: Baseline characteristics for both the main and Ectopic Fat sub-study meet our inclusion criteria and represent a group with overweight or obesity, with characteristics putting them at risk for type 2 diabetes. Findings will be published in peer-reviewed open-access medical journals and provide high-level evidence to inform clinical practice guidelines and public health policy for the use NSBs in sugars reduction strategies. Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT03543644.

1. Introduction

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the single largest contributor of added sugars in the diet [1,2]. Health authorities are universal in discouraging the consumption of SSBs [2,3,4,5] as excess intake is associated with weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [6,7,8,9,10]. Non-nutritive sweetened beverages (NSBs), the greatest largest source of non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS) [11], provide a sweet alternative to SSBs without the calories. Health authorities are near universal in their recommendation that water preferentially replace SSBs. However, these health authorities are mixed in their recommendations regarding NSBs as a replacement strategy for SSBs with some recommending their use [12] and others, including Health Canada and the World Health Organization (WHO), recommending against their use over due to concerns that they have not demonstrated the intended benefits [5,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Whether NSBs are comparable to water as a replacement strategy for SSBs and reduce adiposity and adiposity-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is unclear. NNS mimic the taste of sugar, but are used in much smaller quantities [19], as they are much sweeter than sucrose [20]. The NNS that sweeten NSBs have been shown to be safe [20,21,22,23] and are approved for use in Canada [24] and regulatory authorities globally [25]. NSBs may be sweetened by a single NNS or NNS blends. For example, in Canada, Coke Zero, Diet Coke, Diet Pepsi, and Diet 7UP are sweetened by aspartame and acesulfame-potassium (ace-k), while Diet Orange Crush is sweetened by sucralose alone.

Recent comprehensive syntheses of the evidence of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies have contributed to the uncertainty regarding NNS. A WHO-commissioned systematic review and meta-analysis of NNS concluded that most health outcomes showed no difference, meaning they failed to show the expected re-ductions in body mass index (BMI), body weight, plasma insulin levels, insulin resistance and β-cell function in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or associations with lower risk of NCDs [26]. A second comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs showed that NNS did not result in the expected weight loss and were associated with higher risk of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in prospective cohort studies [27]. An important criticism of these systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs has been their failure to account for the nature of the comparator and the calories displaced by NSBs, as caloric and noncaloric comparators were pooled together or non-caloric comparators were used as the sole comparator, which would lead to an underestimation of the effect of NSBs in their intended substitution for SSBs [28,29,30,31,32]. When analyses were restricted to comparisons with SSBs (allowing for caloric displacement), there were the expected decreases in blood glucose levels and blood pressure in these same syntheses [26,27]. These evidence syntheses also did not differentiate between the food sources that contain NNS, in which it can be difficult to achieve differences in energy as gram amounts of sugars are replaced with milligram amount of NNS with starches and fats as fillers making up the difference by weight [26]. Epidemiologic analyses have proven equally problematic, as baseline or prevalent exposure of NNS and NCD outcomes is well recognized to be at high risk of reverse causality and residual confounding from behavioral clustering [29,31,32,33]. More recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses designed to address these criticisms by looking specifically at the substitution of NSBs for SSBs as a comparison of a single food matrix and the most important source of NNS (i.e., NSBs) and free sugars (i.e., SSBs) in the diet. These systematic reviews and meta-analyses showed the expected differences in adiposity and adiposity-related markers in both the randomized controlled trials [16,34,35,36,37] and prospective cohort studies [38]. These syn-theses reinforced the importance of energy displacement and food matrix and support the shift in dietary guidelines from a focus on single nutrients towards a focus on foods, in recognition that focus on single nutrients may miss important interactions related to the food matrix in which the nutrients are contained [39].

Various biological mechanisms have been invoked to support the signals for concern regarding NNS consumption (e.g., through the brain’s reward center [40], and/or through gastrointestinal sweet-taste receptors [41]), but there is a particular concern that NNSs may induce and promote glucose intolerance through changes to the composition and diversity of the gut microbiome [30,42]. A single study showed a worsening of glucose tolerance and changes in gut microbiota beta-diversity in a post-hoc “responder” group after six days of saccharin capsules administration at the maximum acceptable daily intake (ADI) dose (5 mg/kg of body weight/day) [43]. Despite this study’s methodological weaknesses (short duration, small sample size, before-and-after design etc.), it reinforced a negative view of NNSs in the media [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. More recent intervention trials designed to address the gaps described have failed to confirm these initial results [42,52,53,54], using various single NNS (aspartame, sucralose, and saccharin) in healthy normal weight adults on markers of glycemic control and gut microbiota beta-diversity. However, there is still controversy in this field, as a 2022 study showed a worsening of glucose tolerance and changes in gut microbiota beta-diversity in a different post-hoc “responder” group after 14 days of saccharin and sucralose sachet administration at 34 and 20% of the ADI dose, respectively [55]. These studies still leave many pragmatic questions unanswered such as, dose- and time-dependent effects, the effect of the most commonly consumed NNS and NNS blends (which is the most common way that blends being the most common way NNS are consumed worldwide [25], especially since different NNS may have different physio-logical effects) and in the food sources which they are mostly found (i.e., NSBs) [56,57]. More importantly, none of these studies answered the question of the intended use of NNS, which is to displace calories from sugars, particularly from SSBs for disease prevention.

There is an urgent need to address the remaining uncertainties related to NSBs. Health Canada, in particular, has indicated that studies of sugar reduction strategies that use NNSs with microbiome outcomes are an important research priority [58]. We undertook the Strategies To OPpose SUGARS with Non-nutritive sweeteners Or Water (STOP Sugars NOW) trial, a Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR)-funded randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of a “real world” strategy of SSBs reduction using NSBs on glucose tolerance and gut microbiota changes as well as intermediate cardiometabolic risk factors and mediators. We also undertook a sub-study on liver fat and related ectopic muscle fat and intermediate NAFLD outcomes (Ectopic Fat sub-study), given the recognition of NAFLD as an early metabolic lesion in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and an increasingly common public health problem [59]. To address the issue of the nature of the comparator, we designed a study to assess NSBs in the context of three prespecified substitutions of clinical and public health concern: NSBs for SSBs (“intended substitution” with caloric displacement), water for SSBs (“standard of care substitution” with caloric displacement) and NSBs for water (“reference substitution” without caloric displacement).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

The STOP Sugars NOW trial is a four-week single-center, open label, randomized controlled crossover trial with three arms (SSB, NSB, water) comparing the effect of replacing SSBs with NSBs (“intended replacement”) versus water (“standard of care”) on the gut microbiota diversity and glucose tolerance. After a two-week run-in phase, each participant acted as their own control receiving the three interventions for four-weeks each in a random order, with intervention phases separated by a minimum of a four-week washout phase. All trial visits were conducted at Unity Health Toronto, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON. Canada. The trial protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 [60], and the study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the research ethics board of St. Michael’s Hospital (protocol code: 17-292, 16 February 2018). All participants provided written informed consent to the main trial, and separately but optional, to the Ectopic Fat sub-study. The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03543644), and Supplemental File S1 includes the full trial protocol. All methods described here apply for the Ectopic Fat sub-study except where indicated.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Table 1 shows the detailed list of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants were included if they were consuming at least one 355 mL serving of SSB per day. Additional inclusion criteria include: between the ages of 18 and 75 years, BMI that is classified as overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 for Asian individuals and ≥25 kg/m2 for other individuals), and high waist circumference (using ethnic specific cut-offs [61,62,63,64]) but otherwise healthy with no antibiotic use in the last three months [65,66,67,68,69]. Main exclusion criteria were if they were pregnant or breastfeeding or planning on becoming pregnant during the trial and if they had any disease, among others. The Ectopic Fat sub-study followed the same inclusion and exclusion criteria with the addition of one factor for exclusion: any condition or circumstance which would prevent from having an 1H-MRS scan (e.g., having prostheses or metal implants, tattoos, or claustrophobia).

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

2.3. Randomization and Allocation Concealment

Table 2 shows the Latin square randomization table. Randomization was performed after successful completion of the run-in phase and first visit. Randomization, with no stratification, was conducted centrally by an offsite statistician at the Applied Health Research Centre (AHRC) at St. Michael’s Hospital using the Research Data Capture (REDCap) program. Participants were randomly allocated to six possible sequences using blocked (Latin squares) randomization with a similar number of participants allocated to each treatment sequence. Allocation concealment was achieved by the secured electronic delivery of a single sequence for each consecutive participant. RedCap was chosen as it exceeds privacy and security standards which enables anonymization, secure information storage, retrieval, and sharing of data.

Table 2.

Latin Square Randomization Table.

2.4. Interventions

Table 3 shows the list of intervention beverages and types of NNS sweeteners available for the trial. There were three interventions: SSBs (355 mL, 140 kcal, 42 g sugars per serving); NSBs (355 mL, 0 kcal, 0 g sugars per serving); and water (still or carbonated) (355 mL, 0 kcal, 0 g sugars per serving). To allow for pragmatic substitutions using available market products, the calories of the intervention groups were not matched, and the dose prescription of each intervention (number of 355 mL servings) for each participant was matched to their baseline SSB intake. Participants were provided with the SSB of their choice, equivalent NSB that was sweetened by either acesulfame-potassium (ace-k) or sucralose, as these will be measured objectively as markers of adherence (see below) [71], or water. If participants were consuming NSBs in addition to SSBs, they forwent their NSBs. The beverages given to participants during the trial were not necessarily selected to be in the same lot.

Table 3.

List of the Intervention Beverages and Types of NNS Sweeteners.

2.5. Blinding

Blinding of the participants and trial personnel was not possible due to the nature of the intervention. However, outcome assessors and statisticians were blinded to the identity of the treatments.

2.6. Trial Flow

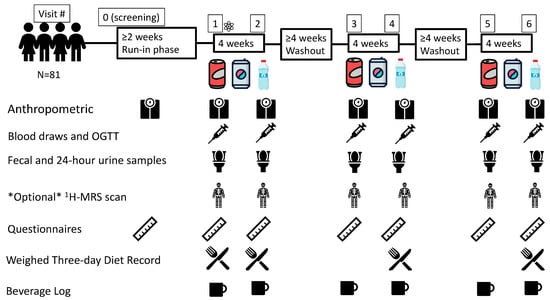

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial and the data collection schedule. Participants were recruited through postings and flyer handouts, transit advertisements, online listings (Craigslist and Kijiji) and through a digital marketing group (Trialfacts). After informed consent review and in-person screening, eligible participants who consented to participate in the trial were instructed on data collection procedures and were enrolled in a minimum two-week run-in phase.

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants through the Trial and the Data Collection Schedule. Questionnaires include Personal Information, Demographic Data and Medical History Questionnaires, Symptoms and Craving/Hunger/Satiety Questionnaires and Case Report Forms.  = Randomization event: AHRC-REDCap program; Blocked (Latin squares) randomization; Allocation concealment; 1H-MRS = proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy;

= Randomization event: AHRC-REDCap program; Blocked (Latin squares) randomization; Allocation concealment; 1H-MRS = proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy;  = Water;

= Water;  = sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB);

= sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB);  = non-nutritive sweetened beverage (NSB); N = number; OGTT = 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test.

= non-nutritive sweetened beverage (NSB); N = number; OGTT = 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test.

= Randomization event: AHRC-REDCap program; Blocked (Latin squares) randomization; Allocation concealment; 1H-MRS = proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy;

= Randomization event: AHRC-REDCap program; Blocked (Latin squares) randomization; Allocation concealment; 1H-MRS = proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy;  = Water;

= Water;  = sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB);

= sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB);  = non-nutritive sweetened beverage (NSB); N = number; OGTT = 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test.

= non-nutritive sweetened beverage (NSB); N = number; OGTT = 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test.

After randomization and for the trial duration, participants were asked to maintain their usual background diet and exercise regimen. Before every visit, participants were instructed to collect a whole stool sample, a 24 h urine sample, and a weighed three-day diet record (3DDR); to consume a minimum of 150 g of carbohydrate for each of the three days prior; and to arrive fasted for 10–12 h [72,73]. Common examples of 150 g of carbohydrates were shared with participants prior to their visit (e.g., 2–3 slices of bread, 1 cup of cooked rice/pasta, 1 medium potato, etc.). At each trial visit, if participants were enrolled in the Ectopic Fat sub-study, they complete an 1H-MRS scan. Then, the standard protocol was followed for the administration of a 2 h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (time points −30, 0, 30, 60, 90, 120) [74], which was followed by breakfast prepared by the study staff.

Once all measures were collected, participants were provided the intervention beverages and beverage log sheets, urine and stool containers and instructions for their next visit. After successful randomization, participants were compensated for their travel expenses and for their time. Participants who were lost to follow-up were compensated for each trial visit that was completed.

The four-week duration of each intervention phase was chosen to allow changes in our family of primary outcomes (glucose tolerance and gut microbiota diversity), as previous studies have seen changes in microbiota diversity with seven days to two weeks intervention [43,55]. To control for any carry-over effects of one beverage type over another, each of the three intervention phases was separated by a minimum four-week washout phase where participants reverted to their regular SSB intake. Participants were given beverage logs to complete over the washout. Antibiotic use during a washout or intervention phase required either prolongation of the washout period or stoppage of the intervention phase followed by a minimum 30-day washout period measured from the time of completion of the antibiotic course [69].

To promote adherence, all intervention beverages were provided either by pick-up by the participant or by home delivery; participants completed beverage log sheets and motivational phone calls and emails were made every two weeks.

2.7. Primary Outcomes

The family of primary outcomes of the main trial includes changes from baseline in oral glucose tolerance, as measured by the glucose incremental area under the curve (iAUC), and the gut microbial beta-diversity, as measured by the weighted UniFrac distance matrix. The weighted UniFrac distance matrix was chosen as it was found to be more accurate [75]. This will be computed using the QIIME2 [76] pipeline with DNA sequences (sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform) from the 16S rRNA gene, with primers targeting the V3–V4 region. The QIIME2 pipeline will be available on GitHub upon request.

The primary outcome of the Ectopic Fat sub-study is changes from baseline in intrahepatocellular lipid (IHCL), as measured by 1H-MRS.

2.8. Secondary Outcomes

The secondary outcomes of the main trial are changes from baseline in waist circumference, body weight, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 2 h plasma glucose (2 h-PG) and the Matsuda whole body insulin sensitivity index (Matsuda ISIOGTT) [77].

The secondary outcomes of the Ectopic Fat sub-study are change from baseline in intramyocellular lipid (IMCL), fatty liver index (FLI) [78], alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), glutamyl transferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

2.9. Adherence Outcomes

Adherence outcomes are changes from baseline in self-reported beverage intake from beverage logs, returned beverage containers, and objective biomarkers of SSBs (increased 13C/12C ratios in serum fatty acids [79] and increased urinary fructose [80]), water (decreased 13C/12C ratios in serum fatty acids [79] and decreased urinary fructose [80]), and NSB (increased urinary acesulfame potassium and/or sucralose [71]) intake.

2.10. Exploratory Outcomes

Exploratory outcomes of the main trial include changes from baseline in blood pressure, fasting blood lipid profile, fasting plasma insulin, 75 g OGTT derived indices (iAUC plasma insulin, maximum concentrations (Cmax) and time to maximum concentrations (Tmax)) of plasma glucose and insulin, mean incremental plasma glucose and insulin, the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) [81,82], beta-cell function as measured by the insulin secretion-sensitivity index-2 (ISSI-2) [83,84], early insulin secretion index [85,86], satiety, hunger, and food cravings, diet quality, alpha-diversity, other beta-diversity indexes and metagenomic inference from compositional data in silico from whole stool [87].

2.11. Power Calculation

Table 4 shows the power (sample size) calculation for the main trial and the Ectopic Fat sub-study, using the “power” package in STATA17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The main trial has over 89% power and the Ectopic Fat sub-study has over 80% power to show a difference between the NSB, water and SSB arms in 60 participants in the two primary outcomes of glucose tolerance and gut microbiota beta-diversity in the main trial and 25 participants in the primary outcome of IHCL in the Ectopic Fat sub-study. Assuming a drop-out rate of 20%, we planned to recruit 75 and 32 participants, respectively.

Table 4.

Power (Sample Size) Calculation for Main Trial and Ectopic Fat Sub-Study.

The main trial is powered to detect a difference of 44.81 mmol/L/min (standard de-viation (SD) = 113 mmol/L/min) (i.e., 20%) in iAUC glucose [88,89] and 0.04 (SD = 0.07) in microbiota beta-diversity [43]. Considering it is a cross-over trial with a within-person correlation of 0.7, these differences were chosen based on effects smaller than the be-ta-diversity and glycemic response effect observed in the study of Suez et al. (2014) [43], which was the only study available at the time. The trial is also powered to detect clinically meaningful differences in all secondary outcomes except the adiposity outcomes (body weight and waist circumference) between the three interventions [35,90,91]. To control for false discovery, the truncated Benjamini-Hochberg method with parallel gatekeeping for control of false discovery will be implemented [93,94,95,96]. By this method the unused portion of the alpha from the primary outcomes is passed onto the secondary family of outcomes if either one of the primary outcomes is statistically significant. The sample size calculations were based on the most conservative alpha estimates from this method. If none of the primary endpoints reaches significance, then the secondary outcomes will be analyzed as exploratory variables without adjustment for false discovery rate. All exploratory out-comes will be assessed without adjustment for false discovery rate.

The Ectopic Fat sub-study is powered to detect a difference of 5% (SD = 10%) in IHCL [92], using a within-person correlation of 0.67. The truncated Benjamini-Hochberg method with parallel gatekeeping procedure will not be used for the Ectopic Fat sub-study, as it is considered exploratory in nature.

2.12. Outcome Assessment

Supplementary File S1 presents the methods for the assessment of the primary, secondary, adherence, and exploratory outcomes.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Data will be analyzed in STATA 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Primary analyses will be according to intention-to-treat (ITT) principle with multiple imputations or other appropriate statistics. Additional prespecified analyses will be undertaken that include completers and the per-protocol analyses. Repeated measures mixed effect models will be used to assess changes in the family of primary outcomes (gut microbiota beta-diversity (weighed UniFrac distance) and mean glucose iAUC (75 g OGTT)) between the groups and in our secondary outcomes (waist circumference, body weight, FPG, 2 h-PG and Matsuda ISIOGTT) with adjustment for sequence effects, trial completion during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, withdrawal/drop-out during the COVID-19 pandemic, and antibiotic use during the trial. Other adjustments will be considered based upon an assessment of any imbalances during the trial. Pairwise comparisons will be performed using Tukey–Kramer adjustment to assess differences for the three prespecified substitutions: SSBs for NSBs (“intended substitution” with caloric displacement), SSBs for water (“standard of care substitution” with caloric displacement) and NSBs for water (“reference substitution” without caloric displacement). We will use the truncated Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate controlling method with a parallel gatekeeping procedure to correct for multiple outcomes for all the primary and secondary endpoint comparisons in the main analysis as described above [93,96]. To assess effect modification, a priori subgroup analysis will be conducted by age, sex, ethnicity, antibiotic use during the trial, baseline BMI, baseline waist circumference, baseline FPG, baseline 2 h-PG, baseline iAUC, medication use, NNS blend consumed from trial beverages in the NSB arm, SSB type and background NNS use. Subgroup analyses by baseline SSB dose (as number of 355 mL serving per day and percent energy from sugars), consumption patterns, energy compensation, trial completion during the COVID-19 pandemic and caffeine intake (cola vs. non-cola beverages) that have emerged as relevant prior to data analyses will also be considered.

3. Results

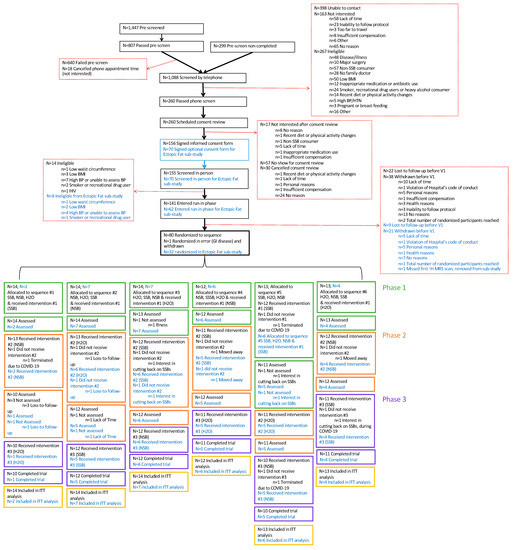

3.1. CONSORT Statement

Figure 2 shows the CONSORT statement for the main trial and the Ectopic Fat sub-study. Enrollment began on 1 June 2018, with the first participant undergoing randomization on 22 November 2018. The last participant finished the Ectopic Fat sub-study on 18 February 2020 (prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic). The main trial was interrupted owing to research closures at St. Michael’s Hospital due to the COVID-19 pandemic between March 2020 and September 2020, which resulted in visits being halted for 10 participants. During this time, participants were placed on a washout period pending the restart of research; any intervention that needed to be stopped prior to completion was restarted from baseline. The trial resumed with the permission of the Research Ethics Board in September 2020 with completion of the last trial participant on 15 October 2020.

Figure 2.

Flow of Participants through the Trial and the Data Collection Schedule. Text in blue refers to the Ectopic Fat sub-study. 1H-MRS= proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; GI = gastrointestinal; H2O = water; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HTN = hypertension; ITT = intention-to-treat; N = number; NSB = non-nutritive sweetened beverage; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage; V = visit; WC = waist circumference.

The planned recruitment was expanded from 75 to 81 participants for the main trial and from 25 to 32 for the Ectopic Fat sub-study to increase the power for the planned analyses. The increase in power was approved before the COVID-19 pandemic and was completed to allow participants already enrolled in the run-in phase to have a chance to participate.

A total of 1088 individuals completed the telephone screening questionnaire, of which 260 were eligible for in-person screening and 156 provided written informed consent. Main reasons for the failed screening included failure to contact (n = 398), lack of interest (n = 163) and ineligibility (n = 267) mainly due to non-consumption of SSBs (n = 57) or the presence of disease (n = 48). After the in-person screening, 141 individuals were eligible for the main trial, of which 62 individuals consented to the Ectopic Fat sub-study. Due to dropouts (main trial = 38; Ectopic Fat sub-study = 21) and loss-to-follow up (main trial = 22; Ectopic Fat sub-study = 9) during the screening and run-in phases, a total of 81 eligible participants (Ectopic Fat sub-study = 32) were randomized to a treatment sequence. One participant met the exclusion criterion for the presence of gastrointestinal disease, was randomized in error to the main trial and was withdrawn shortly after randomization. Their randomization sequence was not reused, and the participant was not counted among the randomized participants and will not be included in any analyses. A total of 66 participants out of 80 completed the main trial (83% retention), and 26 out of 32 participants completed the Ectopic Fat sub-study (81% retention). Of the 10 participants who were enrolled in the main trial during the COVID-19 pandemic, one participant dropped out during the pandemic (due to changes in lifestyle (interest in cutting back on SSB consumption)), three participants who had more than one phase to complete were withdrawn by the investigators (as it was determined there was no reasonable prospect of their completion during the projected subsequent waves of COVID-19), and the remaining six participants who had only a single phase to complete were able to return and finish the trial. The reasons for attrition unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic ranged from lack of time to participate, moving away, change in lifestyle (cutting back on SSB consumption) or loss-to-follow-up.

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

Table 5 shows the baseline characteristics of the 80 randomized participants in the main trial and the 32 participants randomized in the Ectopic Fat sub-study participants. Baseline characteristics are descriptively described here: Mean (SD) age was 42.34 years (12.99 years) (Ectopic Fat sub-study: 42.16 years (12.91 years)), with approximately even sex distribution (main trial, female = 51%; Ectopic Fat sub-study, female = 50%). BMI and waist circumference were 33.71 kg/m2 (6.75 kg/m2) (Ectopic Fat sub-study, 33.70 kg/m2 (6.03 kg/m2)) and 108.69 cm (13.50 cm) (Ectopic Fat sub-study, 110.31 cm (13.67 cm)), respectively. The mean baseline (SD) systolic and diastolic blood pressure were 116.37 mmHg (12.49 mmHg) (Ectopic Fat sub-study: 76.68 mmHg (9.12 mmHg)) and 76.24 mmHg (9.03 mmHg) (Ectopic Fat sub-study, 72.34 mmHg (9.76 mmHg)), respectively. Mean baseline (SD) FPG was 5.57 mmol/L (1.19 mmol/L) (Ectopic Fat sub-study: 5.77 mmol/L (1.75 mmol/L)) and 2 h-PG were 7.26 mmol/L (3.11 mmol/L) (Ectopic Fat sub-study: 7.99 mmol/L (4.05 mmol/L)). Mean baseline (SD) IHCL for the participants in the Ectopic Fat sub-study was 9.7% (9.2%). Most trial participants are of European (main trial: 45%; Ectopic Fat sub-study, 56%) descent. About one-third of participants in the main trial had achieved an undergraduate education (34%), whereas a similar proportion of participants in the Ectopic Fat sub-study had a high school diploma (31%). About half of the participants worked full-time (main trial: 50%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 44%), and one-quarter of participants in the main trial reported drinking no alcohol (26%), with only 4% drinking alcohol daily. Among the Ectopic Fat sub-study, a similar proportion reported drinking alcohol once every 2–3 months (28%) with only 6% drinking alcohol daily.

Table 5.

Baseline Characteristics for the Main Trial and Ectopic Fat Sub-Study.

Overall, 29% and 38% of participants in the main trial and Ectopic Fat sub-study, respectively, reported being on regular medications. Some participants reported taking supplements (main trial: 29%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 25%). Two participants (9%) included in the main trial (one (13%) in the Ectopic Fat sub-study) used marijuana regularly without a medical prescription.

Most participants did not regularly consume NNS in the past six months before baseline (main trial: 55%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 63%), while some participants reported background NNS intake from beverages (main trial: 26%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 31%), table-top added sweeteners (main trial: 6%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 3%), foods (main trial: 5%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 0%), or a mix of these sources (main trial: 8%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 3%). Baseline SSB preference revealed Coca-Cola (main trial: 44%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 53%) as the most popular SSB consumed, with an overall average of 1.84 servings (355 mL) per day (total intake: 653.2 mL/d) in the main trial and 2.02 servings (355 mL) (total intake: 717.1 mL/d) per day in the Ectopic Fat sub-study. From this information, projected NSB equivalent intake indicated that an overwhelming majority of participants consumed a blend of aspartame and ace-k (main trial: 95%; Ectopic Fat sub-study: 94%) during the NSB phase. Overall, baseline characteristics in the Ectopic Fat sub-study were descriptively similar to those in the main trial.

4. Discussion

The STOP Sugars NOW Trial is a pragmatic, single-center, open label, randomized controlled multiple crossover trial with three four-week treatment phases (SSB, NSB, water) comparing the effect of the substitution of NSBs (“intended substitution”) versus water (“standard of care substitution”) for SSBs on the gut microbiota and glucose tolerance as well as other intermediate cardiometabolic outcomes in adults who consume ≥1 SSBs daily and are overweight or obese with a high waist circumference. The Ectopic Fat sub-study uses the same design to assess the effect on ectopic fat in liver (IHCL) by 1H-MRS as well as other ectopic fat in muscle (IMCL) and related intermediate markers of NAFLD. This trial will be the first to investigate the effect of the intended use of NSBs to replace SSBs, compared with the “standard of care” water, in a pragmatic and controlled manner in those who are regular consumers of SSBs and at high risk of the sequelae of overconsumption of SSBs.

Baseline characteristics for both the main and Ectopic Fat sub-study were not different. Overall, the study participants in both the main trial and the Ectopic Fat sub-study represent an overweight or obese group with characteristics putting them at risk for type 2 diabetes and other NCDs.

The NNS tested in the present trial are representative of those available on the market in Canada and globally [97]. Consumption of NSBs has been increasing [11,98] with approximately 10% of Canadians consuming NSBs [99]. Canadian market share data show that Diet Pepsi, Diet Coke and Coke Zero are the leading NSB brands in Canada [100]. As NSBs are the most important food source of NNS, it can be inferred that the blend of aspartame and ace-k, followed by sucralose alone, are the most common NNS in foods in Canada, and this data reflects the global market [97].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The present trial overcomes several limitations of previous trials of the use of NSBs as a replacement strategy for SSBs. First, it uses a “real-world” fully pragmatic design with NSBs products available on the Canadian and global markets [56,100], compared with previous work that mostly administered single NNS in capsule form and often in greater amounts than products available on the market, which limits the generalizability of conclusions [42,43,52,53,54]. Second, comparing the effect of NSBs to SSBs (“intended sub-stitution”) and the standard of care water (“reference substitution”) allows for the dis-entanglement of the effect of energy from that of the NNS, as it has been hypothesized that NNS may have consequences for health independent of energy content that result from the chemical compounds themselves [41,56,101]. The substitution of NSBs for SSBs allows for the displacement of energy, which is often overlooked in controlled trial syntheses, including a recent WHO-commissioned review [26]. The substitution of water for SSBs (“standard of care substitution”) and comparison of water with NSBs (“reference substitution”), will clarify whether NSBs are like water in their effect on gut microbiota and attributing metabolic disease risk. Third, unlike many studies that have investigated changes in the gut microbiota beta-diversity as an outcome [102], the STOP Sugars NOW trial is powered to detect a change in both primary outcomes of glucose tolerance and change in the beta-diversity of the gut microbiota, using Food and Drug Administration recommended statistical analyses [96]. Fourth, our use of objective urinary and serum biomarker analysis to assess adherence to all interventions overcomes many reporting or recall biases. Fifth, our sample population that includes participants who are overweight or obese with a high waist circumference represents an at-risk population for type 2 diabetes. This makes the results of the trial relevant to guidelines and policies for type 2 diabetes prevention. Sixth, the results from this trial will contribute to the development of clinical trial methodologies, especially related to the integration of microbiota data with clinical data, which is an emerging area of research [103]. Finally, our results will be directly translatable to most areas of the world which share similar NNS and NSB availability.

Some limitations remain. First, the multiple crossover design with three treatment phases, two washout periods, and multiple measurements may have contributed to a reduction in retention. Our retention of 82.5% for the main trial and 81.3% for the Ectopic Fat sub-study, however, would meet criteria for good retention [104]. We also anticipated this level of retention in our sample size calculation and have been able to maintain adequate statistical power for our primary and secondary outcomes with good balance in the treatment sequences. Second, as with any intervention trial, participants may un-consciously compensate for the reduced energy and caffeine intake from NSBs or water interventions by consuming additional calories in their background diet [34]. Despite instructions to maintain usual background diets and activity levels throughout the trial, the inventions may also have engendered other health behaviors leading participants to change their diets and activity levels consciously or unconsciously [105]. As part of the ITT principle, any changes resulting from the interventions would be considered an effect of the interventions and will be captured in our analysis of the participant’s 3DDRs, activity logs, and case report forms, and assessed by subgroup analyses. The design which included both negative (SSBs) and positive (water) controls will also help us to isolate the effect of the change in NSBs from other changes which may attenuate or enhance the effects of the interventions. Further, we will be conducting subgroup analysis to explore the effects of caffeine on our outcomes. Third, as most of the participants in the NSB phase consumed a blend of aspartame and ace-k, we will not be able to isolate the effect of a single NNS on glucose tolerance and the gut microbiota. Related to this limitation, our results will not inform the effect of other less-common NNS, such as neotame or saccharin, as these NNS are not used to sweeten commercially available NSBs in Canada. These results, however, will be representative of the product availability in the Canadian, North American, and global market [56,97,100]. Fourth, although our trial sample shows traits akin to the general population of Canada where the prevalence of overweight and obesity is now 63% [106,107] and akin to average SSB consumers in North America [10,11,108], we do acknowledge that there is some evidence of volunteer bias in our sample, as most of our participants represent higher socioeconomic background (higher education and full-time work status). Therefore, we are potentially neglecting inclusion of people who are at higher risk for type 2 diabetes and other NCDs, and who have less access to resources to manage the disease [109,110]. Fifth, the COVID-19 pan-demic posed some challenges. Ten participants were enrolled in the trial during the COVID-19 pandemic, of which six completed the last phase of the trial after a prolonged washout period, three were withdrawn by the investigators for no reasonable prospect of completion, and one dropped out during the pandemic due to changes in lifestyle. It is reasonable to expect that the background diet and lifestyle of these participants and their ability to adhere to the interventions and trial protocol were directly affected by the pandemic. It was decided to adjust for study participation during the pandemic in our primary models and conduct sensitivity analyses in which these participants were excluded in modified ITT, completers, and per protocol analyses. Sixth, the washout period may have been of insufficient duration and may result in carry-over effects from previous the intervention, especially for changes in the gut microbiota. However, the microbiome is very resilient; acute changes in diet or lifestyle revert to baseline within 48 hours [111]. Short-term dietary changes, especially of only one component of the diet, is often not sufficient to majorly perturb the gut microbiome in a permanent way [112]. The STOP Sugars NOW Trial is changing only one aspect in our participant’s diets for a short-term intervention: sugar-sweetened beverage intake for four weeks. During the washout phases, participants were instructed to revert to their usual sugar-sweetened beverage intake, and we believe that the resiliency of the gut microbiome will overcome the short-term dietary changes. Finally, as we are using 16S rRNA gene sequencing to assess gut microbiota outcomes, we will not have species level resolution, and we will not be able to directly infer gut microbiota functions. However, previous research done on the effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on the gut microbiota and the risk for diabetes [42,43,52,53,54], have also sequenced the 16S rRNA gene. Therefore, our results will be directly comparable to the current literature on this topic.

4.2. Implications

The role of NSBs in modifying the risk for type 2 diabetes from SSBs and the extent to which the human gut microbiota might mediate this process is of great importance in understanding chronic disease pathogenesis, prevention, and management for guideline and policy makers. Excess intake of calories from sugars, particularly from SSBs, has been linked to the rise in NCDs [6,7,8,9]. Public health agencies in Canada and around the world have responded by urging the public to reduce their consumption of SSBs [2,113,114,115]. Replacement strategies for SSBs that leverage beverages with the same sweet taste, like NSBs, may be more appealing than water and thus may facilitate a reduction in SSB intake. Although the NNSs used to sweeten NSBs are considered safe by regulatory authorities [22,23], public health recommendations are conflicting [2,18,114,116]. Some research suggests that NNS may increase the risk for type 2 diabetes through changes in the microbiota in humans, but this finding needs confirmation [42,88]. The proposed STOP Sugars NOW trial will provide important data to address this concern using representative NSBs and NNS blends in a representative sample of at-risk obese individuals.

5. Conclusions

The STOP Sugars NOW trial is the first to pragmatically investigate the effect of the intended use of NSBs to replace SSBs compared with the “standard of care” water in those who are regular consumers of SSBs and at high risk of the sequelae of overconsumption of SSBs. We successfully recruited and randomized 80 participants in the main trial and 32 participants in the Ectopic Fat sub-study. Baseline characteristics for both the main and Ectopic Fat sub-study were similar and meet our eligibility criteria. Overall, the study participants in both the main trial and the Ectopic Fat sub-study represent an overweight or obese group with characteristics putting them at risk for type 2 diabetes and other NCDs. Additionally, the study sample is representative of the average SSB consumer in Canada, making the study’s results applicable to disease prevention in target population for public health interventions to reduce SSB intake. The results of this unique trial will be presented at scientific meetings, published in peer-reviewed academic journals, and included in updated systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The results will inform guidelines for NSBs as a replacement strategy for SSBs, compared with “standard of care” (water), aiding in knowledge translation related to the health effects of NSBs in their intended substitution for SSBs; improving health outcomes by educating healthcare providers and patients, stimulating industry innovation; and guiding future research design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/5/1238/s1, File S1: STOP Sugars NOW Study Protocol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.S., T.A.K. and E.M.C.; methodology, J.L.S., T.A.K., A.T., C.T.C., Y.-T.C., R.P.B., D.D.R., E.M.C. and C.L.; software, T.A.K., J.L.S., S.A.-C., N.D.M., D.L. and S.B.M.; validation, T.A.K., J.L.S. and S.B.M.; formal analysis, S.A.-C., D.L. and T.A.K.; investigation, S.A.-C., N.D.M., D.L., S.B.M., L.C., M.E.K., M.S., A.A., R.A., M.E., Y.-T.C., E.M.C. and J.L.S.; resources, J.L.S.; data curation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.-C.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, S.A.-C.; supervision, J.L.S.; project administration, M.S., M.E.K., L.C. and S.B.M.; funding acquisition, J.L.S., T.A.K., E.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through the “Operating Grant: Sugar and Health” program (funding reference number, 152807); Province of Ontario, Ministry of Research and Innovation and Science, Early Research Award (ERA)—Round 13 and the Nutrition Trialist Research Fund at the University of Toronto (a fund established by an inaugural donation from the Calorie Control Council). The Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) and the Ministry of Research, and Innovation’s Ontario Research Fund (ORF) (funding reference numbers, 37544 and 492343 provided the infrastructure for the conduct of this project. S.A.-C. was funded by a CIHR Canadian Graduate Scholarships Master’s Award, the Loblaw Food as Medicine Graduate Award, the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS), and the CIHR Canadian Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award (funding reference number 476251). N.D.M. was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)- Master’s Award, a St. Michael’s Hospital Research Training Centre Scholarship and a Toronto 3D Internship during the conduct of the trial. D.L. was funded by the University of Toronto Department of Nutritional Sciences Graduate Student Fellowship, University of Toronto Fellowship in Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto Supervisor’s Research Grant-Early Researcher Awards, and Dairy Farmers of Canada Graduate Student Fellowships; a scholarship from St. Michael’s Hospital Research Training Centre, and a University of Toronto School of Graduate Studies Conference Grant during the conduct of the trial. T.A.K. by a Toronto 3D Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Award. L.C. was a Mitacs-Elevate post-doctoral fellow jointly funded by the Government of Canada and the Canadian Sugar Institute (Feb 2019–Aug 2021). A.A. and Y.T.C. were funded by an undergraduate research opportunity program (UROP) Summer student position. R.A. was funded by a Toronto 3D Internship during the conduct of the trial. J.L.S. was funded by the PSI Graham Farquharson Knowledge Translation Fellowship, Canadian Diabetes Association Clinician Scientist award, CIHR INMD/CNS New Investigator Partnership Prize, and Banting & Best Diabetes Centre Sun Life Financial New Investigator Award. None of the sponsors have a role in any aspect of the present trial, including the design and conduct of the trial; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript or decision to publish.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of St. Michael’s Hospital (protocol code: 17-292, 16 February 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Aspects of this work were presented at the St. Michael’s Hospital Annual Elevator Pitch Competition (2019 and 2020), Toronto, Canada, the University of Toronto Three-Minute Thesis Competition (2020), Toronto, Canada, the Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group (DNSG)’s 37, 38 and 39 International Symposium on Diabetes and Nutrition, Kerkrade, Netherlands (37; 2019), Online (38; 2021), and Anavyssos, Greece (39; 2022), the 2021 Canadian Student Health Research Forum (online), the American Society for Nutrition Live Online 2021 Conference, the Canadian Nutrition Society’s Thematic 2021 Online Conference and the Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences Science Innovation Showcase (2022). We would like to thank the Guelph Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (Aileen Hawke, Andrea Arjoon-Mohabir; Aishwarya Krishnaraj; Gregory Fougere; Xinye Qi), Government of Canada, The Center for the Analysis of Genome Evolution and Function (CAGEF) and Mount Sinai Services for conducting the analysis. We would also like to thank the many student volunteers (Al-Amin Ahamed, Amanda Beck, Bavina Sivayogeswaran, Bersabhe Solomon, Cassandra Busuttil, Duha Alnadvi, Gabrielle Has-Ellison, Haneen Youssef, Jennifer Halteh, Joeie Schwartz, Larissa Chomka, Linda Lin, Megha Patel, Natalie Amlin, Ophelia Fong, Stephanie Robayo, Veronica Lazebnik, Yasemin Sandirli) who have helped in the conduct of this trial.

Conflicts of Interest

S.A.-C. avoids consuming NSBs and SSBs and has received an honorarium from the international food information council (IFIC) for a talk on artificial sweeteners, the gut microbiome, and the risk for diabetes. N.D.M. was a former employee of Loblaw Companies Limited and current employee of Enhanced Medical Nutrition. She has completed consulting work for contract research organizations, restaurants, start-ups, the International Food Information Council, and the American Beverage Association, all of which occurred outside of the submitted work. T.A.K. has taken honorarium for lectures from International Food Information Council (IFIC) and Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS; formerly ILSI North America). LC was previously employed as a casual clinical coordinator at INQUIS Clinical Research, Ltd. (formerly Glycemic Index Laboratories, Inc.), a contract research organization. M.E.K. has received funding from a Toronto 3D PhD Scholarship award and the CIHR Canadian Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award and is a part-time employee at INQUIS Clinical Research, Ltd., a contract research organization. R.A. has received funding from the CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarships Master’s Award and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS). M.E. has received funding from the United Soybean Board (the United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] Soy “Check-off” Program) and a CIHR Canadian Graduate Scholarships Master’s Award. V.S.M. has received funding from the Government of Canada through the Canada Research Chair Endowment, Connaught New Researcher Award, The Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition, University of Toronto; Temerty Faculty of Medicine Pathway Grant, University of Toronto; Canada Foundation for Innovation; Ontario Research Fund. She has served as a consultant for the City and County of San Francisco for litigation related to health warning labels on soda. R.P.B. has received industrial grants, including those matched by the Government of Canada through the Canada Research Chair Endowment, and/or travel support or consulting fees largely related to work on brain fatty acid metabolism from Arctic Nutrition, Bunge Ltd., DSM, Fonterra Inc, Mead Johnson, Natures Crops International, Nestec Inc. Pharmavite, and Sancero Inc. He is on the executive of the International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids and held a meeting on behalf of Fatty Acids and Cell Signaling, both of which rely on corporate sponsorship. Dr. Bazinet has given expert testimony in relation to supplements and the brain. D.D.R. has received research support from Pulse Canada, the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers Association, and the Ontario Bean Growers Association. He has no other conflict of interest to declare. A.J.H. holds investigator-initiated research funds from Dairy Farmers of Canada. C.W.C.K. has received grants or research support from the Advanced Food Materials Network, Agriculture and Agri-Foods Canada, Almond Board of California, American Pistachio Growers, Barilla, Calorie Control Council, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canola Council of Canada, International Nut and Dried Fruit Council, International Tree Nut Council Research and Education Foundation, Loblaw Brands, Pulse Canada, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers and Unilever; has received in-kind research support from the Almond Board of California, American Peanut Council, Barilla, California Walnut Commission, Kellogg Canada, Loblaw Companies, Quaker (PepsiCo), Primo, Unico, Unilever, WhiteWave Foods; has received travel support or honorariums from the American Peanut Council, American Pistachio Growers, Barilla, California Walnut Commission, Canola Council of Canada, General Mills, International Nut and Dried Fruit Council, International Pasta Organization, Loblaw Brands Ltd., Nutrition Foundation of Italy, Oldways Preservation Trust, Paramount Farms, Peanut Institute, Pulse Canada, Sabra Dipping, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Sun-Maid, Tate & Lyle, Unilever and White Wave Foods; has served on the scientific advisory board for the International Tree Nut Council, International Pasta Organization, Lantmannen, McCormick Science Institute, Oldways Preservation Trust, Paramount Farms and Pulse Canada; is a member of the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium, executive board member of the Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes; is on the Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee for Nutrition Therapy of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes; and is a director of the Toronto 3D Knowledge Synthesis and Clinical Trials Foundation. E.M.C. has received research support from Ocean Spray Cranberries and Lallemand Health Solutions; and has received consultant fees or speaker and travel support from Danone and Lallemand Health Solutions. She held the Lawson Family Chair in Microbiome Nutrition Research at The University of Toronto. J.L.S. has received research support from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Ontario Research Fund, Province of Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation and Science, Canadian Institutes of health Research (CIHR), Diabetes Canada, American Society for Nutrition (ASN), International Nut and Dried Fruit Council (INC) Foundation, National Honey Board (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA] honey “Checkoff” program), Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS; formerly ILSI North America), Pulse Canada, Quaker Oats Center of Excellence, The United Soybean Board (USDA soy “Checkoff” program), The Tate and Lyle Nutritional Research Fund at the University of Toronto, The Glycemic Control and Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Fund at the University of Toronto (a fund established by the Alberta Pulse Growers), The Plant Protein Fund at the University of Toronto (a fund which has received contributions from IFF), and The Nutrition Trialists Network Research Fund at the University of Toronto (a fund established by an inaugural donation from the Calorie Control Council). He has received food donations to support randomized controlled trials from the Almond Board of California, California Walnut Commission, Peanut Institute, Barilla, Unilever/Upfield, Unico/Primo, Loblaw Companies, Quaker, Kellogg Canada, Danone, Nutrartis, Soylent, and Dairy Farmers of Canada. He has received travel support, speaker fees and/or honoraria from ASN, Danone, Dairy Farmers of Canada, FoodMinds LLC, Nestlé, Abbott, General Mills, Nutrition Communications, International Food Information Council (IFIC), Calorie Control Council, International Sweeteners Association, International Glutamate Technical Committee, Phynova, and Brightseed. He has or has had ad hoc consulting arrangements with Perkins Coie LLP, Tate & Lyle, and Inquis Clinical Research. He is a former member of the European Fruit Juice Association Scientific Expert Panel and former member of the Soy Nutrition Institute (SNI) Scientific Advisory Committee. He is on the Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committees of Diabetes Canada, European Association for the study of Diabetes (EASD), Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS), and Obesity Canada/Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons. He serves or has served as an unpaid member of the Board of Trustees and an unpaid scientific advisor for the Carbohydrates Committee of IAFNS. He is a member of the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC), Executive Board Member of the Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group (DNSG) of the EASD, and Director of the Toronto 3D Knowledge Synthesis and Clinical Trials foundation. His spouse is an employee of AB InBev. D.L., S.B.M., M.S., A.T., C.T.C., A.A., Y.T.C., C.L., and L.A.L. reports no relevant competing interests.

References

- Brisbois, T.D.; Marsden, S.L.; Anderson, G.H.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Estimated intakes and sources of total and added sugars in the Canadian diet. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1899–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Sugar, Heart Disease and Stroke. Available online: https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/2017-position-statements/sugar-ps-eng.ashx (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Diabetes Canada. Sugar & Diabetes. Available online: https://www.diabetes.ca/en-CA/advocacy---policies/our-policy-positions/sugar---diabetes (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Cut down on Added Sugars. Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/DGA_Cut-Down-On-Added-Sugars.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Health Canada. Canada’s Dietary Guidelines for Health Professionals and Policy Makers. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/static/assets/pdf/CDG-EN-2018.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; O’Connor, L.; Ye, Z.; Mursu, J.; Hayashino, Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Forouhi, N.G. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ 2015, 315, h3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalath, V.H.; de Souza, R.J.; Ha, V.; Mirrahimi, A.; Blanco-Mejia, S.; Di Buono, M.; Jenkins, A.L.; Leiter, L.A.; Wolever, T.M.; Beyene, J.; et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and incident hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; Huang, Y.; Reilly, K.H.; Li, S.; Zheng, R.; Barrio-Lopez, M.T.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Zhou, D. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of hypertension and CVD: A dose-response meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Li, Y.; Pan, A.; De Koning, L.; Schernhammer, E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Long-term consumption of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of mortality in US adults. Circulation 2019, 139, 2113–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Rother, K.I. Trends in the consumption of low-calorie sweeteners. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/ScientificReport_of_the_2020DietaryGuidelinesAdvisoryCommittee_first-print.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Johnson, R.K.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Carson, J.A.; Després, J.-P.; Hu, F.B.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Otten, J.J.; Towfighi, A.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Low-calorie sweetened beverages and cardiometabolic health: A science advisory from the american heart association. Circulation 2018, 138, e126–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Available online: https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/suppl/2019/12/20/43.Supplement_1.DC1/Standards_of_Care_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Diabetes UK. Evidence-Based Nutrition Guidelines for the Prevention and Management Of Diabetes. Available online: https://diabetes-resources-production.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/resources-s3/2018-03/1373_Nutrition%20guidelines_0.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Rios-Leyvraz, M.; Montez, J. Health Effects of the Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 10–174.

- World Health Organization. Launch Event for the Public Consultation on the Draft WHO Guideline on Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2022/07/15/default-calendar/launch-event-for-the-public-consultation-on-the-draft-who-guideline-on-use-of-non-sugar-sweeteners (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Sievenpiper, J.L.; Chan, C.B.; Dworatzek, P.D.; Freeze, C.; Williams, S.L. Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee—Chapter 11: Nutrition Therapy. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Sweeteners. Available online: http://www.inspection.gc.ca/food/labelling/food-labelling-for-industry/sweeteners/eng/1387749708758/1387750396304?chap=0 (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Kroger, M.; Meister, K.; Kava, R. Low-calorie sweeteners and other sugar substitutes: A review of the safety issues. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2006, 5, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, B.A.; Roberts, A.; Nestmann, E.R. Critical review of the current literature on the safety of sucralose. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 106, 324–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. American Heart Association/American Diabetes Association Scientific Statement:Non-nutritive Sweeteners: A Potentially Useful Option—with Caveats. Available online: http://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/2012/ada-aha-sweetener-statement.html (accessed on 9 November 2018).

- Fitch, C.; Keim, K.S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Use of nutritive and nonnutritive sweeteners. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. 9. List of Permitted Sweeteners (Lists of Permitted Food Additives). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/food-additives/lists-permitted/9-sweeteners.html (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Russell, C.; Baker, P.; Grimes, C.; Lindberg, R.; Lawrence, M.A. Global trends in added sugars and non-nutritive sweetener use in the packaged food supply: Drivers and implications for public health. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toews, I.; Lohner, S.; de Gaudry, D.K.; Sommer, H.; Meerpohl, J.J. Association between intake of non-sugar sweeteners and health outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ 2019, 364, k4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.B.; Abou-Setta, A.M.; Chauhan, B.F.; Rabbani, R.; Lys, J.; Copstein, L.; Mann, A.; Jeyaraman, M.M.; Reid, A.E.; Fiander, M.; et al. Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. CMAJ 2017, 189, E929–E939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S. Non-sugar sweeteners and health. BMJ 2019, 364, k5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Low-energy sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: Is there method in the madness? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mela, D.J.; McLaughlin, J.; Rogers, P.J. Perspective: Standards for research and reporting on low-energy (“artificial”) sweeteners. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwell, M.; Gibson, S.; Bellisle, F.; Buttriss, J.; Drewnowski, A.; Fantino, M.; Gallagher, A.M.; De Graaf, K.; Goscinny, S.; Hardman, C.A. Expert consensus on low-calorie sweeteners: Facts, research gaps and suggested actions. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2020, 33, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievenpiper, J.L.; Khan, T.A.; Ha, V.; Viguiliouk, E.; Auyeung, R. The importance of study design in the assessment of nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2017, 189, E1424–E1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Malik, V.S.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Letter by Khan et al. regarding article, “Artificially sweetened beverages and stroke, coronary heart disease, and all-cause mortality in the women’s health initiative”. Stroke 2019, 50, e167–e168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.; Hogenkamp, P.; De Graaf, C.; Higgs, S.; Lluch, A.; Ness, A.; Penfold, C.; Perry, R.; Putz, P.; Yeomans, M. Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, N.D.; Khan, T.A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.; Chiavaroli, L.; Au-Yeung, F.; Lee, J.J.; Noronha, J.C.; Comelli, E.M.; Blanco Mejia, S.; et al. Association of Low- and No-Calorie Sweetened Beverages as a Replacement for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages with Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e222092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laviada-Molina, H.; Molina-Segui, F.; Pérez-Gaxiola, G.; Cuello-García, C.; Arjona-Villicaña, R.; Espinosa-Marrón, A.; Martinez-Portilla, R.J. Effects of nonnutritive sweeteners on body weight and BMI in diverse clinical contexts: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Khan, T.; Malik, V.; Hill, J.; Jeppesen, P.; Rahelic, D.; Kahleova, H.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Kendall, C.W.; Sievenpiper, J. Relation of Change or Substitution of Low Calorie Sweetened Beverages with Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Khan, T.A.; McGlynn, N.; Malik, V.S.; Hill, J.O.; Leiter, L.A.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Rahelić, D.; Kahleová, H.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Relation of Change or Substitution of Low-and No-Calorie Sweetened Beverages with Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievenpiper, J.L.; Dworatzek, P.D. Food and dietary pattern-based recommendations: An emerging approach to clinical practice guidelines for nutrition therapy in diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes. 2013, 37, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.R.; Reister, E.J.; Cheon, E.; Mattes, R.D. Low calorie sweeteners differ in their physiological effects in humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.V.; Small, D.M. Physiological mechanisms by which non-nutritive sweeteners may impact body weight and metabolism. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Santibanez, R.; Aguirre, C.; Galgani, J.E.; Garrido, D. Short-term impact of sucralose consumption on the metabolic response and gut microbiome of healthy adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A.; et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. Artificial Sweeteners May Disrupt Body’s Blood Sugar Controls. Available online: https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/09/17/artificial-sweeteners-may-disrupt-bodys-blood-sugar-controls/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Kirkey, S. Fake Sugars Linked to Obesity, Heart Disease. Available online: http://nationalpost.com/news/0717-na-sugar (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Faherty, S. Artificial Sweeteners May Have Despicable Impacts on Gut Microbes. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/artificial-sweeteners-may-have-despicable-impacts-on-gut-microbes/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Sifferlin, A. Artificial Sweeteners are Linked to Weight Gain —Not Weight Loss. Available online: http://time.com/4859012/artificial-sweeteners-weight-loss/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Vergano, D. Artificial Sweeteners May Trigger Blood Sugar Risks. Available online: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/09/140917-sweeteners-artificial-blood-sugar-diabetes-health-ngfood/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Leung, W. Sugar Substitutes Associated with Weight Gain and Health Problems, Study Says. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/sugar-substitutes-linked-to-weight-gain-and-health-problems-study-says/article35704562/ (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Brait, E. More Research Needed into the Effects Sugar Substitutes Have on Health. Available online: https://www.thestar.com/life/2017/07/17/more-research-needed-into-the-effects-sugar-substitutes-have-on-health.html (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Thompson, D. Do Artificial Sweeteners Raise Odds for Obesity? Available online: http://www.webmd.com/food-recipes/news/20170717/do-artificial-sweeteners-raise-odds-for-obesity#1 (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Serrano, J.; Smith, K.R.; Crouch, A.L.; Sharma, V.; Yi, F.; Vargova, V.; LaMoia, T.E.; Dupont, L.M.; Serna, V.; Tang, F. High-dose saccharin supplementation does not induce gut microbiota changes or glucose intolerance in healthy humans and mice. Microbiome 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Y.; Friel, J.; Mackay, D. The Effects of Non-Nutritive Artificial Sweeteners, Aspartame and Sucralose, on the Gut Microbiome in Healthy Adults: Secondary Outcomes of a Randomized Double-Blinded Crossover Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Y.; Friel, J.K.; MacKay, D.S. The effect of the artificial sweeteners on glucose metabolism in healthy adults: A randomized, double-blinded, crossover clinical trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Cohen, Y.; Valdés-Mas, R.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Federici, S.; Zmora, N.; Leshem, A.; Heinemann, M.; Linevsky, R. Personalized microbiome-driven effects of non-nutritive sweeteners on human glucose tolerance. Cell 2022, 185, 3307–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, B.A.; Carakostas, M.C.; Moore, N.H.; Poulos, S.P.; Renwick, A.G.J.N.r. Biological fate of low-calorie sweeteners. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, O.-J.M.; Wang, D.D.; Shams-White, M.; Bleich, S.N.; Foreyt, J.; Franz, M.; Johnson, G.; Manning, B.T.; Mattes, R.; Pi-Sunyer, X. Research priorities for studies linking intake of low-calorie sweeteners and potentially related health outcomes: Research methodology and study design. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e000547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research in Partnership with Health Canada. Operating Grant: Sugar and Health ARCHIVED. Available online: https://www.researchnet-recherchenet.ca/rnr16/vwOpprtntyDtls.do?prog=2554&printfriendly=true (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Taylor, R.; Al-Mrabeh, A.; Sattar, N. Understanding the mechanisms of reversal of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2018. Available online: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/documents/tcps2-2018-en-interactive-final.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Alberti, K.G.M.; Zimmet, P.; Shaw, J. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005, 366, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.; Eckel, R.; Grundy, S.; Zimmet, P.; Cleeman, J.; Donato, K.; Fruchart, J.; James, W.; Loria, C.; Smith Jr, S. A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 8–31.

- Lear, S.; James, P.; Ko, G.; Kumanyika, S. Appropriateness of waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio cutoffs for different ethnic groups. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zmora, N.; Weissbrod, O.; Bar, N.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Kosower, N.; Malka, G.; Rein, M. Bread affects clinical parameters and induces gut microbiome-associated personal glycemic responses. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huaman, J.-W.; Mego, M.; Manichanh, C.; Cañellas, N.; Cañueto, D.; Segurola, H.; Jansana, M.; Malagelada, C.; Accarino, A.; Vulevic, J. Effects of prebiotics vs a diet low in FODMAPs in patients with functional gut disorders. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrügger, S.; Gøbel, R.J.; Vestergaard, H.; Licht, T.R.; Frøkiær, H.; Linneberg, A.; Hansen, T.; Gupta, R.; Pedersen, O.; Kristensen, M. Two randomized cross-over trials assessing the impact of dietary gluten or wholegrain on the gut microbiome and host metabolic health. J. Clin. Trials. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roager, H.M.; Vogt, J.K.; Kristensen, M.; Hansen, L.B.S.; Ibrügger, S.; Mærkedahl, R.B.; Bahl, M.I.; Lind, M.V.; Nielsen, R.L.; Frøkiær, H. Whole grain-rich diet reduces body weight and systemic low-grade inflammation without inducing major changes of the gut microbiome: A randomised cross-over trial. Gut 2019, 68, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvers, K.T.; Wilson, V.J.; Hammond, A.; Duncan, L.; Huntley, A.L.; Hay, A.D.; Van Der Werf, E.T. Antibiotic-induced changes in the human gut microbiota for the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in primary care in the UK: A systematic review. BMJ open 2020, 10, e035677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Daskaklopoulou, S.; Dasgupta, K.; McBrien, K.; Butalia, S.; Zarnke, K.; Nerenberg, K.; Harris, K.; Nakhla, M.; Cloutier, L.; et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logue, C.; Dowey, L.R.C.; Strain, J.J.; Verhagen, H.; McClean, S.; Gallagher, A.M. Application of Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry To Determine Urinary Concentrations of Five Commonly Used Low-Calorie Sweeteners: A Novel Biomarker Approach for Assessing Recent Intakes? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4516–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, C.; Randle, P. Effects of low-carbohydrate diet and diabetes mellitus on plasma concentrations of glucose, non-esterified fatty acid, and insulin during oral glucose-tolerance tests. Lancet 1963, 1, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, H.L.; Butler, F.K.; Francis, J.O.S. The effect of prior carbohydrate intake on the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes 1960, 9, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Study Group on Diabetes Mellitus & World Health Organization. Diabetes Mellitus: Report of a WHO Study Group [meeting held in Geneva from 11 to 16 February 1985]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985; pp. 7–93.

- Lozupone, C.; Knight, R. UniFrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, M.; DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: Comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]