Christian Orthodox Fasting as a Traditional Diet with Low Content of Refined Carbohydrates That Promotes Human Health: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

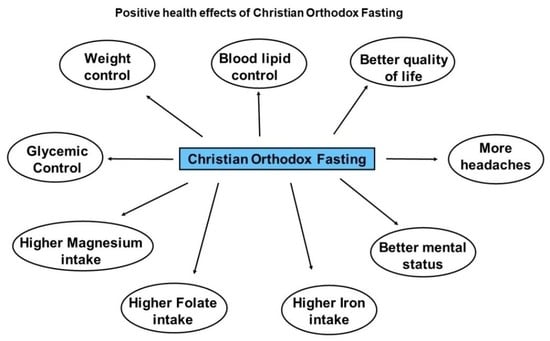

3. Results

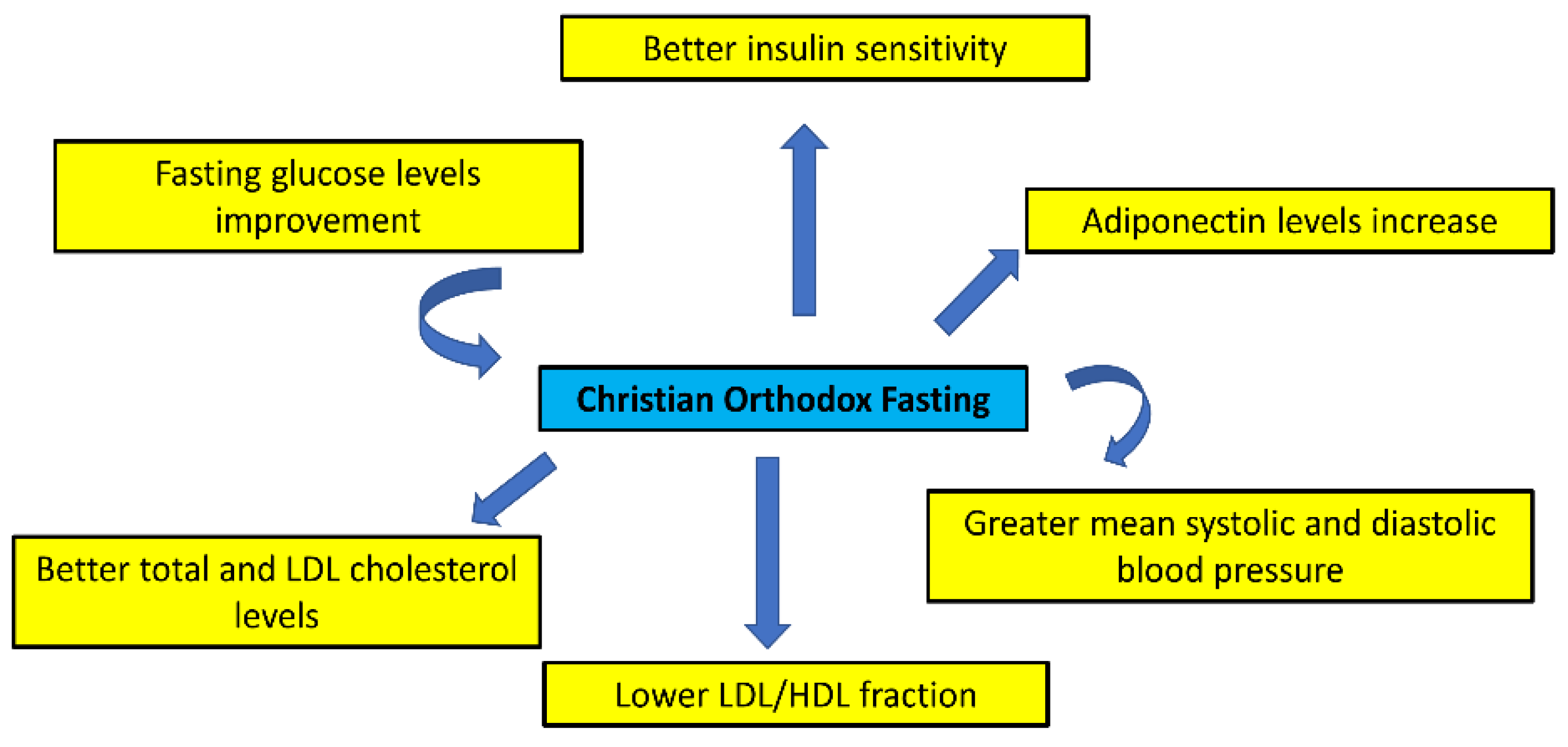

3.1. Cardiometabolic Health Status

| Cardiometabolic Factor | Study Population | Study Period | Main Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Control | Cross-sectional study in 50 Athonian monks (mean age: 38.7 ± 10.6 years) | Restrictive and non-restrictive fasting days | Glucose indices and HOMA-IR in normal levels | [15] |

| 43 males from the general population that regularly fast (20–45 y of age) and 57 age-matched Athonian monks | Restrictive and non-restrictive days | Monks had better HOMA-IR than the general population | [16] | |

| 37 strict fasters (18 males, 19 females, mean age 43.0 ± 13.1 years), vs. 48 age-and sex-matched controls (21 males, 27 females; mean age 38.6 ± 9.6 years) | 40 days | Significant decrease in glucose levels after the fasting period | [5] | |

| 120 Greek adults were followed longitudinally (60 fasters, 60 non-fasters) | 1 year | No changes in fasting glucose of fasters | [17] | |

| 36 (25 women & 11 men) monks from 5 Greek monasteries | 40 days | No changes in fasting glucose | [18] | |

| Blood Lipid Control | 10 Greek Christian Orthodox monks aged 25–65 years, with BMI >30 kg/m2 | 1 fasting week vs. non-fasting week (Measurements on Palm Sunday week (fasting) and the week following Pentecost Sunday (non-fasting) | End of the non-fasting week: ↑* total and LDL cholesterol NS ↑ HDL cholesterol During the fasting week: ↓ total: HDL cholesterol ↑ serum triglycerides | [19] |

| 120 Greek adults were followed longitudinally (60 fasters, 60 non-fasters) | 1 year | ↓** 12.5% total cholesterol & ↓ 15.9% LDL cholesterol in faster than non-fasters. ↓ LDL/HDL in fasters, NS change on HDL cholesterol in fasters Similar results were found when the pre- and after-fasting values of fasters were compared | [17] | |

| 36 (25 women & 11 men) monks from 5 Greek monasteries | 40 days | ↓ dietary and plasma cholesterol ↑ triglycerides ↓ LDL/HDL during fasting | [18] | |

| 37 overweight but healthy adults followed a hypocaloric diet based on Orthodox fasting 23 BMI-matched healthy adults followed a hypocaloric, time-restricted eating plan | 7 weeks | Lower total cholesterol after Orthodox fasting than time-restricted fasting (178.40 ± 34.14 vs. 197.09 ± 29.61 mg/dL, p = 0.028) Lower HDL cholesterol after Orthodox fasting than time-restricted fasting (51.01 ± 11.66 vs. 60.13 ± 15.93 mg/dL, p = 0.013) | [21] | |

| 29 overweight but healthy adults followed a hypocaloric diet based on Orthodox fasting 16 age- and weight-matched healthy adults followed a hypocaloric, time-restricted eating plan | 7 weeks and 6 weeks follow up after the intervention | Total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol were reduced at 7 weeks and increased at 6 weeks after Orthodox fasting cessation | [22] | |

| 60 Greek Orthodox participants, 30 with dyslipidemia and 30 without dyslipidemia who followed the Greek Orthodox fasting | 7 weeks | In both groups: ↓ fasting glucose, ↓ HDL, ↓ LDL and ↓ triglyceride levels ↑ Hemoglobin, ↑ hematocrit, ↑ iron and ↑ ferritin levels ↓ vitamin B12 and calcium levels Better cholesterol levels improvements on people with dyslipidemia | [20] | |

| Blood Pressure Control | 38 devout Christian Orthodox fasters and 29 matched controls living in Crete | 1 year (measurements before and at the end of the three major fasting periods) | Fasters had ↑ mean SBP and SBP than controls. ↓ BP during the non-fasting period Blood lipids were significantly associated with SBP/DBP at most measurements | [24] |

| 10 Greek Christian Orthodox monks aged 25–65 years, with BMI >30 kg/m2 | 1 fasting week vs. non-fasting week (Measurements on Palm Sunday week (fasting) and the week following Pentecost Sunday (non-fasting) | ↑ SBP while fasting | [10] |

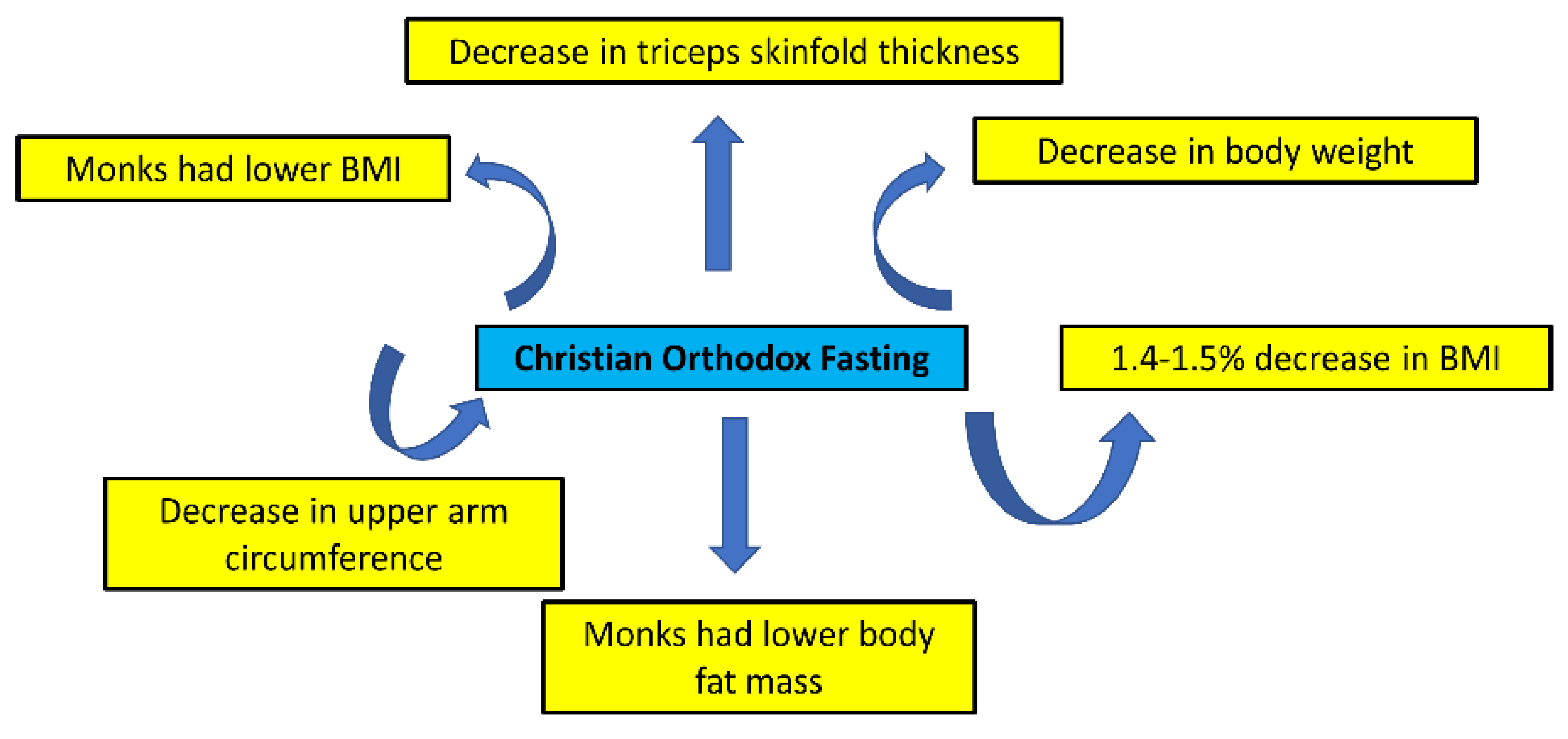

3.2. Weight Control

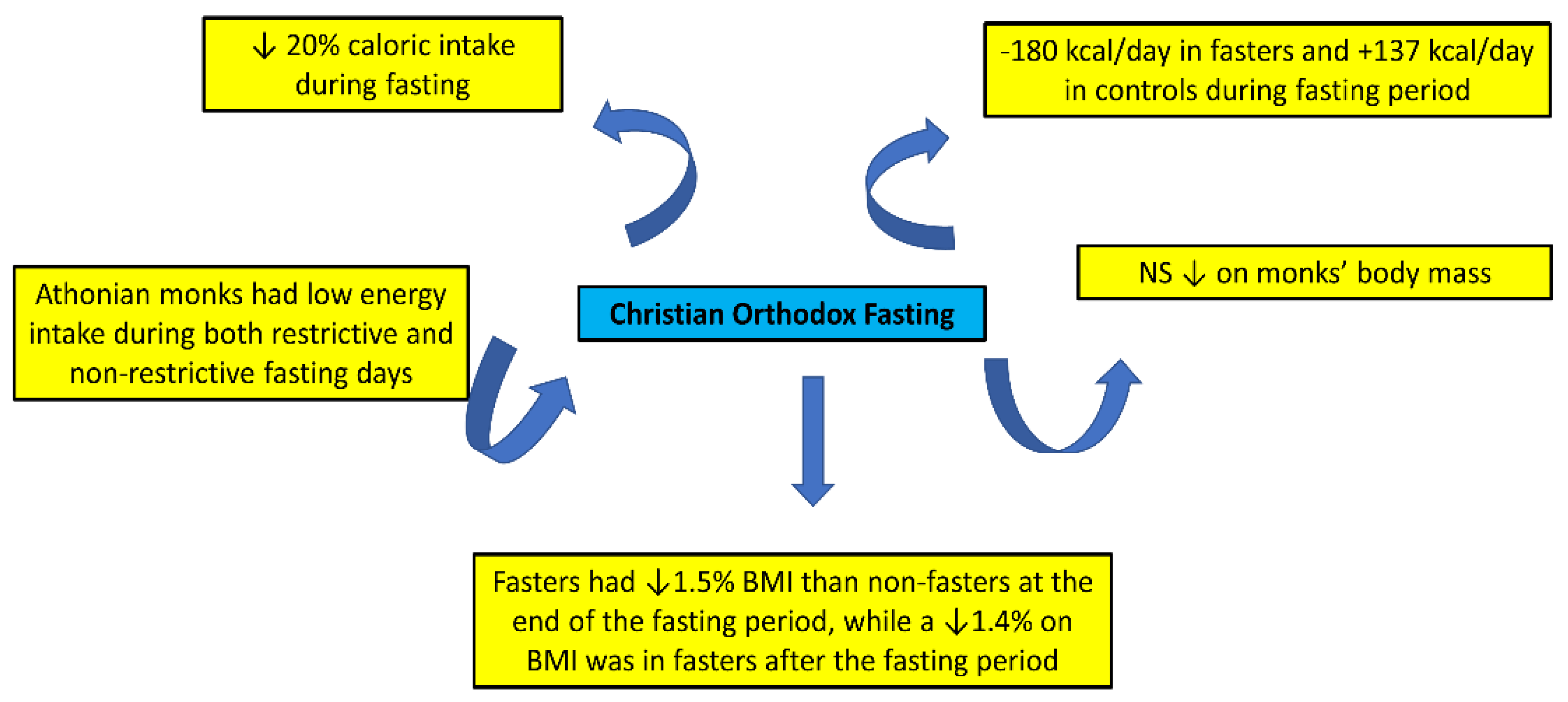

3.3. Nutrient Intakes and Sufficiency Status

| Nutrients | Study Population | Study Period | Main Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 36 (25 women and 11 men) monks from 5 Greek monasteries | 40 days | ↓* 20% caloric intake during fasting | [18] |

| 120 Greek adults were followed longitudinally (60 fasters, 60 non-fasters) | 1 year | −180 kcal/day in fasters and +137 kcal/day in controls during fasting period | [4] | |

| 50 Athonian monks (mean age: 38.7 ± 10.6 years) and 43 males from the general population that regularly fast (20–45 y of age) and 57 age-matched Athonian monks | Restrictive and non-restrictive fasting days | Athonian monks had low energy intake during both restrictive and non-restrictive fasting days | [15,16] | |

| Macronutrients and foods | 50 Athonian monks (mean age = 38.7 ± 10.6 years) | Restrictive and non-restrictive fasting days | ↓* carbohydrate and saturated fat intakes ↑** protein during the “restrictive days” | [15] |

| 10 Greek Christian Orthodox monks aged 25–65 years, with BMI >30 kg/m2 | 1 fasting week vs. non-fasting week | ↓ intakes of total and saturated and trans fats ↑ fiber during fasting ↑ legumes and fish/seafood during fasting, ↑ dairy products, meat and eggs after the fasting week | [19] | |

| 120 Greek adults were followed longitudinally (60 fasters, 60 non-fasters) | 1 year | Fasters (vs. controls) ↓ dietary cholesterol, total fat, saturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids and protein, and ↑ fiber at the end of the fast | [4] | |

| 35 Greek Christian Orthodox strict fasters (n = 17 male, n = 18 female; mean age: 43.6 ± 13.2 years) and 24 controls (n = 11 male, n = 13 female; mean age 39.8 ± 7.6 years) | 40 days Measurements before and near completion of the Christmas fasting | ↑ fiber intake | [26] | |

| 38 devout Christian Orthodox fasters and 29 matched controls living in Crete | 1 year (measurements before and at the end of the three major fasting periods) | ↑ fruit and vegetable consumption during the fasting periods | [24] | |

| Micronutrients | 38 devout Christian Orthodox fasters and 29 matched controls living in Crete | 1 year (measurements before and at the end of the three major fasting periods) | ↓ sodium intake ↑ magnesium intake ↑ folate intake ↓ calcium intake during fasting | [24] |

| 10 Greek Christian Orthodox monks aged 25–65 years, with BMI >30 kg/m2 | 1 fasting week vs. non-fasting week | ↑ folate intake ↑ iron intake | [19] | |

| 35 Greek Christian Orthodox strict fasters (n = 17 male, n = 18 female; mean age: 43.6 ± 13.2 years) and 24 controls (n = 11 male, n = 13 female; mean age: 39.8 ± 7.6 years) | 40 days Measurements before and near completion of the Christmas fasting | longterm religious fasting did not negatively affect iron status fasters ↑ ferritin levels and ↓ total iron-binding capacity, especially females | [26] | |

| 120 Greek adults were followed longitudinally (60 fasters, 60 non-fasters) | 1 year | no differences for other vitamins or minerals, before and after fasting, except for vitamin B2 ↓ calcium intake during fasting | [4] | |

| 50 Athonian monks (mean age: 38.7 ± 10.6 years) and 43 males from the general population that regularly fast (20–45 y of age) and 57 age-matched Athonian monks | Restrictive and non-restrictive fasting days | ↓ vitamin D levels and ↑ PTH with normal serum calcium levels | [15,16] | |

| 37 strict fasters (18 males, 19 females, mean age 43.0 ± 13.1 years), and 48 age- and sex-matched controls (21 males, 27 females; mean age 38.6 ± 9.6 years) | 40 days Measurements before and near completion of the Christmas fasting | ↓ vitamin A & E levels during the fasting period for fasters These changes were related to changes in total cholesterol Vitamin E levels were correlated with changes in LDL and total cholesterol/HDL ratio | [5] | |

| 60 Greek Orthodox participants, 30 with dyslipidemia and 30 without dyslipidemia, who followed the Greek Orthodox fasting | 7 weeks | In both groups: ↓ vitamin B12 and calcium levels | [20] |

3.4. Headaches

3.5. Lifestyle and Mental Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Bloomer, R.J. The impact of religious fasting on human health. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; E Canale, R.; E Marshall, K.; Kabir, M.M.; Bloomer, R.J. Impact of caloric and dietary restriction regimens on markers of health and longevity in humans and animals: A summary of available findings. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinton, R.K.; Ciccazzo, M. Influences on Eastern Orthodox Christian Fasting Beliefs and Practices. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2007, 46, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.O.; Linardakis, M.; Bervanaki, F.N.; Tzanakis, N.E.; Kafatos, A.G. Greek Orthodox fasting rituals: A hidden characteristic of the Mediterranean diet of Crete. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarri, K.; Bertsias, G.; Linardakis, M.; Tsibinos, G.; Tzanakis, N.; Kafatos, A. The Effect of Periodic Vegetarianism on Serum Retinol and α-tocopherol Levels. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2009, 79, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinopoulou, A.; Kafatos, A. Impact of Christian Orthodox Church dietary recommendations on metabolic syndrome risk factors: A scoping review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2021, 35, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549028 (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Yang, B.; Glenn, A.J.; Liu, Q.; Madsen, T.; Allison, M.A.; Shikany, J.M.; Manson, J.E.; Chan, K.H.K.; Wu, W.-C.; Li, J.; et al. Added Sugar, Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative and a Network Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, D.; Peloso, G.M.; Herman, M.A.; Dupuis, J.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Smith, C.E.; McKeown, N.M. Beverage Consumption and Longitudinal Changes in Lipoprotein Concentrations and Incident Dyslipidemia in US Adults: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e014083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklina, E.V.; Park, S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption and Lipid Profile: More Evidence for Interventions. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e015061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeneck, M.; Iggman, D. The effects of foods on LDL cholesterol levels: A systematic review of the accumulated evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, K.L. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2015, 53, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Karlsen, M.C.; Chung, M.; Jacques, P.F.; Saltzman, E.; Smith, C.E.; Fox, C.S.; McKeown, N.M. Potential link between excess added sugar intake and ectopic fat: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 74, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinopoulou, A.; McGowan, R.; Brogan, Y.; Armstrong, J.; Pagkalos, I.; Hassapidou, M.; Kafatos, A. Associations between Christian Orthodox Church Fasting and Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund’s Cancer Prevention Recommendations. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; A Persynaki, A.; A Petróczi, A.; E Barkans, E.; Mulrooney, H.; Kypraiou, M.; Tzotzas, T.; Tziomalos, K.; Kotsa, K.; A A Tsioudas, A.; et al. Health benefits and consequences of the Eastern Orthodox fasting in monks of Mount Athos: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Petróczi, A.; Folkerts, D.; Kypraiou, M.; Mulrooney, H.; Naughton, D.P.; Persynaki, A.; Zebekakis, P.; Skoutas, D.; et al. Christian Orthodox fasting in practice: A comparative evaluation between Greek Orthodox general population fasters and Athonian monks. Nutrition 2018, 59, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O Sarri, K.; E Tzanakis, N.; Linardakis, M.K.; Mamalakis, G.D.; Kafatos, A.G. Effects of Greek orthodox christian church fasting on serum lipids and obesity. BMC Public Health 2003, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basilakis, A.; Kiprouli, K.; Mantzouranis, S.; Konstantinidis, T.; Dionisopoulou, M.; Hackl, J.M.; Balogh, D. Nutritional Study in Greek-Orthodox Monasteries—Effect of a 40-Day Religious Fasting. Akt Erna Med. 2002, 27, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, A.; Vardavas, C.; Hatzis, C.; Kafatos, A. Calcium, nutrient and food intake of Greek Orthodox Christian monks during a fasting and non-fasting week. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, A.S.; Moysidis, D.V.; Tsagkaris, C.; Vouloagkas, I.; Karagiannidis, E.; Kartas, A.; Vlachopoulos, N.; Konstantinou, G.; Sofidis, G.; Stalikas, N.; et al. Impact of religious fasting on metabolic and hematological profile in both dyslipidemic and non-dyslipidemic fasters. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 76, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Adamidou, L.; Dimakopoulos, G.; Karalazou, P.; Thisiadou, K.; Makedou, K.; Zebekakis, P.; Kotsa, K. Implementation of Christian Orthodox fasting improves plasma adiponectin concentrations compared with time-restricted eating in overweight premenopausal women. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 73, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Adamidou, L.; Antonopoulou, V.; Karalazou, P.; Thisiadou, K.; Mitrofanova, E.; Mulrooney, H.; Petróczi, A.; Zebekakis, P.; et al. Effects of orthodox religious fasting versus combined energy and time restricted eating on body weight, lipid concentrations and glycaemic profile. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 72, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Adamidou, L.; Polyzos, S.A.; Karalazou, P.; Thisiadou, K.; Zebekakis, P.; Makedou, K.; Kotsa, K. Similar late effects of a 7-week orthodox religious fasting and a time restricted eating pattern on anthropometric and metabolic profiles of overweight adults. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 72, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarri, K.; Linardakis, M.; Codrington, C.; Kafatos, A. Does the periodic vegetarianism of Greek Orthodox Christians benefit blood pressure? Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, S.; Kurdi, M.; Bemt, B.J.F.V.D. Impact of Fasting on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 78, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.O.; Kafatos, A.G.; Higgins, S. Is religious fasting related to iron status in Greek Orthodox Christians? Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 94, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridou, A.; Rodopaios, N.E.; Mougios, V.; Koulouri, A.-A.; Vasara, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Skepastianos, P.; Hassapidou, M.; Kafatos, A. Effects of Periodic Religious Fasting for Decades on Nutrient Intakes and the Blood Biochemical Profile. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsikostas, D.; Thomas, A.; Gatzonis, S.; Ilias, A.; Papageorgiou, C. An Epidemiological Study of Headache Among the Monks of Athos (Greece). Headache 1994, 34, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkara, T.; Kılıç, K. How Does Fasting Trigger Migraine? A Hypothesis. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2013, 17, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, B.K.; Olesen, J. Symptomatic and nonsymptomatic headaches in a general population. Neurology 1992, 42, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, P.; Manzoni, G.C. Fasting Headache. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2010, 14, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açik, M.; Çakiroğlu, F.P. Evaluating the Relationship between Inflammatory Load of a Diet and Depression in Young Adults. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2019, 58, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjibade, M.; Assmann, K.E.; Andreeva, V.A.; Lemogne, C.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Prospective association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of depressive symptoms in the French SU.VI.MAX cohort. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Scott, T.; Gao, X.; Maras, J.E.; Bakun, P.J.; Tucker, K.L. Mediterranean Diet, Healthy Eating Index 2005, and Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Puerto Rican Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 276–281.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merakou, K.; Kyklou, E.; Antoniadou, E.; Theodoridis, D.; Doufexis, E.; Barbouni, A. Health-related quality of life of a very special population: Monks of Holy Mountain Athos, Greece. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 3169–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chliaoutakis, J.E.; Drakou, I.; Gnardellis, C.; Galariotou, S.; Carra, H.; Chliaoutaki, M. Greek Christian Orthodox Ecclesiastical Lifestyle: Could It Become a Pattern of Health-Related Behavior? Prev. Med. 2002, 34, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, K.; Linardakis, M.; Tzanakis, N.; Kafatos, A. Adipose DHA inversely associated with depression as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2008, 78, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanaki, C.; Rodopaios, N.E.; Koulouri, A.; Pliakas, T.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Vasara, E.; Skepastianos, P.; Serafeim, T.; Boura, I.; Dermitzakis, E.; et al. The Christian Orthodox Church Fasting Diet Is Associated with Lower Levels of Depression and Anxiety and a Better Cognitive Performance in Middle Life. Nutrients 2021, 13, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodopaios, N.E.; Mougios, V.; Konstantinidou, A.; Iosifidis, S.; Koulouri, A.-A.; Vasara, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Skepastianos, P.; Dermitzakis, E.; Hassapidou, M.; et al. Effect of periodic abstinence from dairy products for approximately half of the year on bone health in adults following the Christian Orthodox Church fasting rules for decades. Arch. Osteoporos. 2019, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishy, S.M.; Askari, G.; Mohammadi, H.; Campbell, M.S.; Khorvash, F.; Arab, A. Associations between potential inflammatory properties of the diet and frequency, duration, and severity of migraine headaches: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Sancassiani, F.; Contu, M.P.; Latorre, M.; Di Slavatore, M.; Fornaro, M.; Bhugra, D. Mediterranean Diet and its Benefits on Health and Mental Health: A Literature Review. Clin. Pr. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2020, 16, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Mantzorou, M.; Serdari, A.; Bonotis, K.; Vasios, G.; Pavlidou, E.; Trifonos, C.; Vadikolias, K.; Petridis, D.; Giaginis, C. Evaluating Mediterranean diet adherence in university student populations: Does this dietary pattern affect students’ academic performance and mental health? Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Löf, M.; Chen, R.; Hultman, C.M.; Fang, F.; Sandin, S. Mediterranean diet and depression: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koufakis, T.; Karras, S.N.; Zebekakis, P.; Kotsa, K. Orthodox religious fasting as a medical nutrition therapy for dyslipidemia: Where do we stand and how far can we go? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koufakis, T.; Karras, S.; Antonopoulou, V.; Angeloudi, E.; Zebekakis, P.; Kotsa, K. Effects of Orthodox religious fasting on human health: A systematic review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2439–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and nutritional aspects. of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: A global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.J. Flexitarian Diets and Health: A Review of the Evidence-Based Literature. Front. Nutr. 2017, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestell, C.A. Flexitarian Diet and Weight Control: Healthy or Risky Eating Behavior? Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonstad, S.; Butler, T.; Yan, R.; Fraser, G.E. Type of Vegetarian Diet, Body Weight, and Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Meller, S. Can We Say What Diet Is Best for Health? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimokoti, R.W.; Millen, B.E. Nutrition for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Med. Clin. North Am. 2016, 100, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Macchi, C.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Mediterranean diet and health status: An updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 17, 2769–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinopoulou, A.; Pagkalos, I.; Hassapidou, M.; Kafatos, A. Dietary Patterns in Adults Following the Christian Orthodox Fasting Regime in Greece. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 803913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Population | Study Period | Main Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 43 males from the general population that regularly fast (20–45 y of age) and 57 age-matched Athonian monks | Data were collected during both a restrictive and a non-restrictive day | Monks had lower BMI and lower body fat mass | [16] |

| 36 (25 women & 11 men) monks from 5 Greek monasteries | 40 days | Fasting led to a decrease in weight, upper arm circumference and triceps skinfold thickness | [18] |

| 10 Greek Christian Orthodox monks aged 25–65 years, with BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 1 fasting week vs. non-fasting week Measurements on Palm Sunday week (fasting) and the week following Pentecost Sunday (non-fasting) | NS ↓* on monks’ body mass | [19] |

| 120 Greek adults were followed longitudinally (60 fasters, 60 non-fasters) | 1 year | Fasters had a ↓ 1.5% BMI than non-fasters at the end of the fasting period, while a ↓ 1.4% on BMI was in fasters after the fasting period | [17] |

| Study Population | Main Results | References |

|---|---|---|

| 166 monks (mean age 45.5 ± 13.0 years) from two monasteries and one skete | Monks had ↓* physical activity levels than the general Greek male population and believed that their physical health was worse than the general public, but they had ↑** mental health status | [35] |

| 20–65-year-old people who followed the Greek Christian Orthodox lifestyle | Adoption of this lifestyle was related to healthier behaviors independently of socio-demographic factors and health status | [36] |

| 24 strict fasters and 27 controls | No difference in depressive symptoms distribution, adipose tissue DHA was inversely associated with depression, adherence to the Christian Orthodox diet was correlated with adipose DHA levels compared to controls, which may protect against chronic diseases | [37] |

| 105 fasters and 107 non-fasters | Lower levels of anxiety and depression scores and better cognitive function in people who fast vs. those who do not fast | [38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giaginis, C.; Mantzorou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Gialeli, M.; Troumbis, A.Y.; Vasios, G.K. Christian Orthodox Fasting as a Traditional Diet with Low Content of Refined Carbohydrates That Promotes Human Health: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051225

Giaginis C, Mantzorou M, Papadopoulou SK, Gialeli M, Troumbis AY, Vasios GK. Christian Orthodox Fasting as a Traditional Diet with Low Content of Refined Carbohydrates That Promotes Human Health: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients. 2023; 15(5):1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051225

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiaginis, Constantinos, Maria Mantzorou, Sousana K. Papadopoulou, Maria Gialeli, Andreas Y. Troumbis, and Georgios K. Vasios. 2023. "Christian Orthodox Fasting as a Traditional Diet with Low Content of Refined Carbohydrates That Promotes Human Health: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence" Nutrients 15, no. 5: 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051225

APA StyleGiaginis, C., Mantzorou, M., Papadopoulou, S. K., Gialeli, M., Troumbis, A. Y., & Vasios, G. K. (2023). Christian Orthodox Fasting as a Traditional Diet with Low Content of Refined Carbohydrates That Promotes Human Health: A Review of the Current Clinical Evidence. Nutrients, 15(5), 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051225