Dietary Strategies to Reduce Triglycerides in Women of Reproductive Age: A Simulation Modelling Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

2.2. Dietary Scenarios

2.3. Modelling and Analysis

3. Results

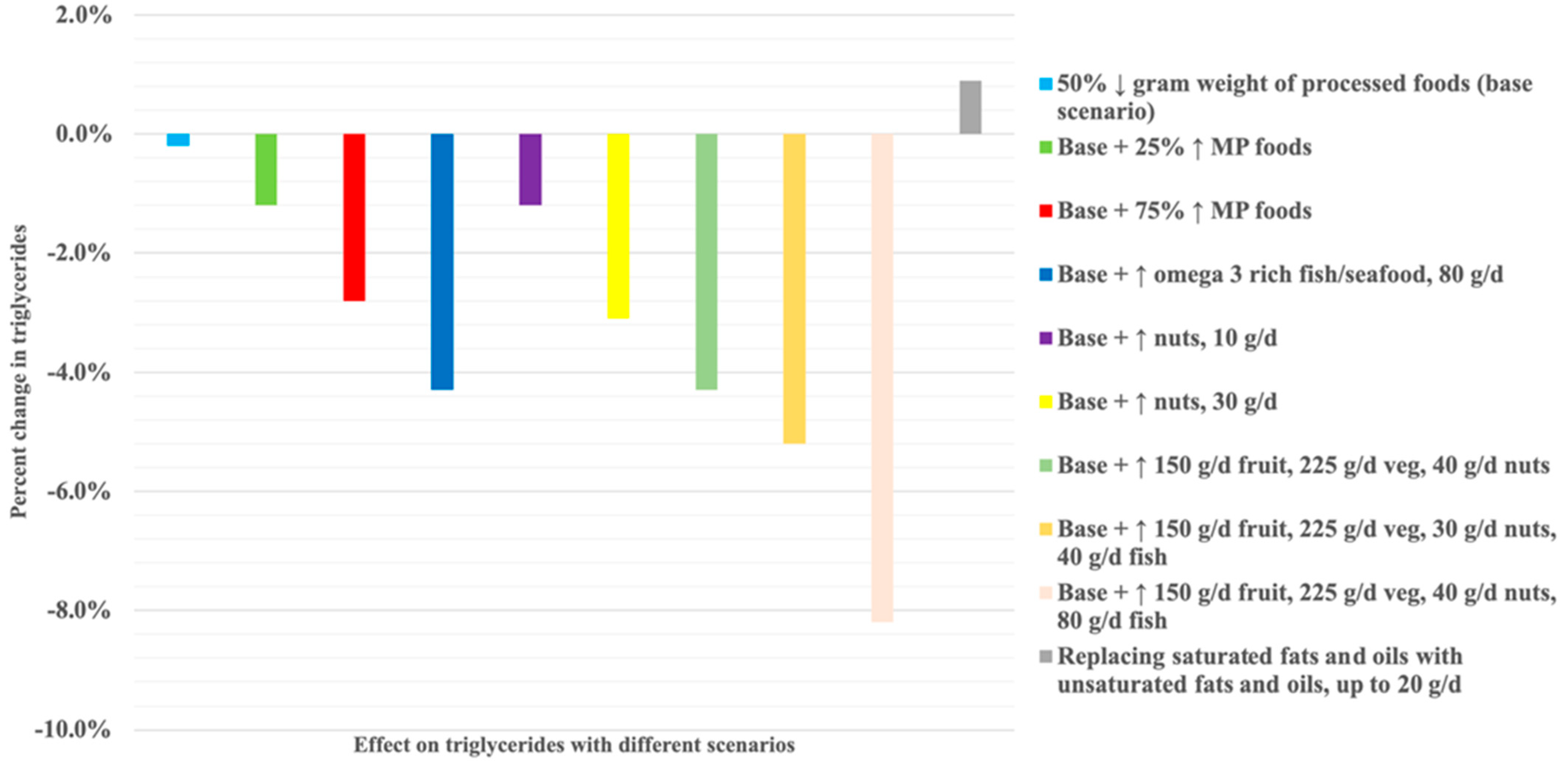

Scenario Modelling on Estimated Triglyceride Concentrations and Nutrient Profile

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Comparison to Other Studies

4.3. Possible Explanations, Implications, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. WHO (2006) Reproductive Health Indicators. Reproductive Health and Research Guidelines for Their Generation, Interpretation and Analysis for Global Monitoring. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43185/924156315X_eng.pdf;jsessionid=13280E8CC5E65685D35F6AF1DA27B394?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Devarshi, P.P.; Legette, L.L.; Grant, R.W.; Mitmesser, S.H. Total estimated usual nutrient intake and nutrient status biomarkers in women of childbearing age and women of menopausal age. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, G.D.; Schoenaker, D.A.; Mihrshahi, S.; Dobson, A.J. How do women’s diets compare with the new Australian dietary guidelines? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.; Jacob, C.M.; Barker, M.; Fall, C.H.D.; Hanson, M.; Harvey, N.C.; Inskip, H.M.; Kumaran, K.; Cooper, C. Healthcare . 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Linné, Y.; Dye, L.; Barkeling, B.; Rössner, S. Long-term weight development in women: A 15-year follow-up of the effects of pregnancy. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, R.A.; Rizzo, M.; Clifton, S.; Carmina, E. Lipid levels in polycystic ovary syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1073–1079.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, C.L.; Lassi, Z.S.; Grieger, J.A.; Ali, A.; Jankovic-Karasoulos, T.; Roberts, C.T.; Andraweera, P.H. Cardio-metabolic risk factors among young infertile women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2020, 127, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieger, J.A.; Bianco-Miotto, T.; Grzeskowiak, L.E.; Leemaqz, S.Y.; Poston, L.; McCowan, L.M.; Kenny, L.C.; Myers, J.E.; Walker, J.J.; Dekker, G.A.; et al. Metabolic syndrome in pregnancy and risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective cohort of nulliparous women. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieger, J.A.; Leemaqz, S.Y.; Knight, E.J.; Grzeskowiak, L.E.; McCowan, L.M.; Dekker, G.A.; Roberts, C.T. Relative importance of metabolic syndrome components for developing gestational diabetes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 305, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, A.N.; Wong, J.; Appelblom, H.; Ross, G.P.; Kouru, H.; Williams, P.F.; Sairanen, M.; Hyett, J.A. A Novel Early Pregnancy Risk Prediction Model for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2019, 45, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.; Sabico, S.; Alnaami, A.M.; Al-Musharaf, S.; Fouda, M.A.; Turkestani, I.Z.; Al-Ajlan, A.; Alshingetti, N.M.; Alokail, M.S.; Al-Daghri, N.M. Early-Pregnancy Metabolic Syndrome and Subsequent Incidence in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Arab Women. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Huo, L.; Yuan, N.; Sun, J.; Du, J.; Nan, M.; Ji, L. Risk prediction model of gestational diabetes mellitus based on nomogram in a Chinese population cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshara, A.; Cohen, E.; Goldberg, E.; Lilos, P.; Garty, M.; Krause, I. Triglyceride levels and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal large study. J. Investig. Med. 2016, 64, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotevall, A.; Johansson, S.; Wilhelmsen, L.; Rosengren, A. Increased levels of triglycerides, BMI and blood pressure and low physical activity increase the risk of diabetes in Swedish women. A prospective 18-year follow-up of the BEDA study. Diabet. Med. 2004, 21, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjellvik, V.; Sakshaug, S.; Strøm, H. Body mass index, triglycerides, glucose, and blood pressure as predictors of type 2 diabetes in a middle-aged Norwegian cohort of men and women. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 4, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Udell, J.A.; Lu, H.; Redelmeier, D.A. Failure of fertility therapy and subsequent adverse cardiovascular events. CMAJ 2017, 189, E391–E397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis, P.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Kauffman, R.P. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): Long-term metabolic consequences. Metabolism 2018, 86, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, B.; Toulis, K.A.; Thomas, N.; Gokhale, K.; Martin, J.; Webber, J.; Keerthy, D.; Jolly, K.; Saravanan, P.; Nirantharakumar, K. Increased risk of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus, a target group in general practice for preventive interventions: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesi, S.; Habibi, N.; Silva, T.R.; Cheung, N.; Torkel, S.; Tay, C.T.; Quinteros, A.; Winter, H.; Teede, H.; Mousa, A.; et al. Assessing the influence of preconception diet on female fertility: A systematic scoping review of observational studies. Hum. Reprod. Update 2023, 29, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, J.M.; Kellett, J.E.; Balsells, M.; Garcia-Patterson, A.; Hadar, E.; Sola, I.; Gich, I.; van der Beek, E.M.; Castaneda-Gutierrez, E.; Heinonen, S.; et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Diet: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Examining the Impact of Modified Dietary Interventions on Maternal Glucose Control and Neonatal Birth Weight. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1346–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, J.; Nie, J. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; White, M. Characterisation of UK diets according to degree of food processing and associations with socio-demographics and obesity: Cross-sectional analysis of UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008-12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cediel, G.; Reyes, M.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Martinez Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A.; Corvalan, C.; Uauy, R. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the Chilean diet (2010). Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 2), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, N.; Leemaqz, S.Y.-L.; Grieger, J.A. Modelling the Impact of Reducing Ultra-Processed Foods Based on the NOVA Classification in Australian Women of Reproductive Age. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J. 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Multisociety Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Primary Prevention. JAMA Cardiol 2019, 4, 488–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide 2011-13 Catalogue No. 4363.0.55.001. 2015. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4363.0.55.001Chapter1002011-13 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. FSANZ. AUSNUT 2011-13. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science-data/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/foodnutrient/Determining-the-amount-of-added-sugars-and-free-sugars-in-foods-listed-in-the-AUSNUT-201113-dataset (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Louie, J.C.; Barclay, A.W.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Assigning glycemic index to foods in a recent Australian food composition database. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Poor Diet. 2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/food-nutrition/poor-diet/contents/poor-diet-in-adults (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Machado, P.P.; Steele, E.M.; Louzada, M.; Levy, R.B.; Rangan, A.; Woods, J.; Gill, T.; Scrinis, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed food consumption drives excessive free sugar intake among all age groups in Australia. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gobbo, L.C.; Falk, M.C.; Feldman, R.; Lewis, K.; Mozaffarian, D. Effects of tree nuts on blood lipids, apolipoproteins, and blood pressure: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and dose-response of 61 controlled intervention trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.; Young, J.; Lean, M.E.J.; Lara, J. Consumption of fish and vascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Atherosclerosis 2017, 266, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, B.A.; Thompson, S.V.; Edwards, C.G.; Skinner, S.K.; Niemiro, G.M.; Burd, N.A.; Holscher, H.D.; Teran-Garcia, M.; Khan, N.A. Dietary Fiber Is Independently Related to Blood Triglycerides Among Adults with Overweight and Obesity. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 3, nzy094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, N.; Livingstone, K.M.; Edwards, S.; Grieger, J.A. Do Older Women of Reproductive Age Have Better Diet Quality than Younger Women of Reproductive Age? Nutrients 2021, 13, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; O’Keefe, J.H. Effects of dietary fats on blood lipids: A review of direct comparison trials. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, H. Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 199–213. ISBN 978-1-4612-1694-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; McQueen, M.; Dagenais, G.; Wielgosz, A.; Lear, S.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Yi, S.; et al. Association of dietary nutrients with blood lipids and blood pressure in 18 countries: A cross-sectional analysis from the PURE study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; San-Cristobal, R.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Corella, D.; Castaner, O.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gomez, A.M.; Warnberg, J.; et al. Use of Different Food Classification Systems to Assess the Association between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Cardiometabolic Health in an Elderly Population with Metabolic Syndrome (PREDIMED-Plus Cohort). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Palacios, S.; Oncina-Canovas, A.; Garcia-de-la-Hera, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Corella, D.; Schroder, H.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gomez, A.M.; Warnberg, J.; et al. Increased ultra-processed food consumption is associated with worsening of cardiometabolic risk factors in adults with metabolic syndrome: Longitudinal analysis from a randomized trial. Atherosclerosis 2023, 377, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Eat For Health. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Providing the Scientific Evidence for Healthier Australian Diets. 2013. Available online: www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n55 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Liu, K.; Hui, S.; Wang, B.; Kaliannan, K.; Guo, X.; Liang, L. Comparative effects of different types of tree nut consumption on blood lipids: A network meta-analysis of clinical trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 219e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients 2010, 2, 652–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Krauss, R.M. Public health guidelines should recommend reducing saturated fat consumption as much as possible: YES. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.A.; Villani, A.; Mantzioris, E. Preferences for dietary oils and fats in cooking and food preparation methods: A cross-sectional analysis of Australian adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 130, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, C.; Schiller, K.; Schulze, M.B. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and type 2 diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2013, 13, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufs, U.; Parhofer, K.G.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Hegele, R.A. Clinical review on triglycerides. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 99–109c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scenario | Strategy | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (base model) | Reducing NOVA processed and ultra-processed foods (PFs): the base model. | Based on current intake of discretionary choices in Australian diets being twice as high than recommendations [33] and results from our previous simulation modelling among Australian women of reproductive age that showed 56.2% of energy intake was consumed from processed foods contributing 60.1% SFAs, 82.7% added sugar, and 82.7% sodium [27]. A 50% reduction in PFs may be a simple approach to reduce energy intake, processed foods, and discretionary choices, thereby reducing the detrimental impact on cardiometabolic health. This is the base model and is included in all subsequent scenarios except Scenario 6 which is the replacement of oils. |

| 2 | Scenario 1 plus replacing PFs with NOVA unprocessed/minimally processed foods. | The Australian diet is typically low in unprocessed/minimally processed foods such as vegetables, fruits, cereals, milk/fermented milks, poultry, fish, and seafood that are important sources of healthy nutrients [34]. |

| 3 | Scenario 1 plus replacing PFs with high-omega-3 foods. | Although nuts and fatty fish that are rich in omega 3 fatty acids have been shown to reduce triglycerides [35,36], intake in the Australian population is suboptimal [33]. |

| 4 | Scenario 1 plus replacing PFs with fruits and vegetables. | Higher intakes of dietary fibre have been associated with lower triglyceride levels [37]. Vegetables and fruits are two major sources of fibre but less than a third (28.2%) of Australian adults consume sufficient amounts of fibre [33], and a majority of women of reproductive age do not meet the recommended intake for vegetables (85.4%) or fruits (73.8%) [38]. |

| 5 | Scenario 1 plus replacing PFs with different combinations of food choices in Scenarios 2–4. | Examining different combinations of potentially feasible increases in healthier foods such as nuts, vegetables, and fruits. |

| 6 | Replacing higher saturated fatty acid oils with higher poly-and/or monounsaturated fatty acid oils. | Compared to SFAs, intake of monounsaturated fats (e.g., α-linolenic acid and oleic acid) and polyunsaturated fats found in flaxseed, olive, canola, and sesame oils has been shown to reduce triglyceride levels [39]. |

| Study Variable | Included Participants |

|---|---|

| Age (years): Mean (SD) | 36.38 (8.16) |

| BMI (kg/m2): Mean (SD) | 26.56 (6.32) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L): Mean (SD) | 1.47 (0.36) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L): Mean (SD) | 4.85 (0.71) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L): Median (IQR) | 0.90 (0.70–1.20) |

| Smoking status: n (%) | |

| Never smoked | 362 (59.74) |

| Ex-smoker | 165 (27.23) |

| Current smoker | 79 (13.04) |

| Country of birth: n (%) | |

| Australia/New Zealand | 443 (73.1) |

| Other | 163 (26.9) |

| Family history of diabetes: n (%) | |

| No | 427 (70.46) |

| Yes | 179 (29.54) |

| Nutrient | All Food Intake, Baseline | Total PFs 1 | MP 2 | PCI 3 | Fruits | Vegetables | Nuts | High-Omega-3 Fish 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram weight (g) | 3113 | 874 | 1898 | 13.6 | 211 | 111 | 3.0 | 2.2 |

| Energy including fibre (kJ) | 7661 | 5110 | 245 | 1470 | 451 | 290 | 71.6 | 24.5 |

| Protein (g) | 79.1 | 46.6 | 0.1 | 26.6 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Fat (g) | 67.1 | 45.5 | 3.6 | 13 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.4 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 202 | 136 | 6.8 | 30.6 | 22.3 | 6.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Sugars (g) | 94 | 52.3 | 6.8 | 11.5 | 20.9 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Added sugars (g) | 46.5 | 37.2 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Free sugars (g) | 53 | 38.5 | 6.8 | 0.7 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fibre (g) | 20.6 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Alcohol (g) | 9.1 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Retinol equivalents (µg) | 779 | 344 | 14.1 | 120 | 71.2 | 229 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Total folate equivalents (µg) | 532 | 377 | 72.3 | 0.2 | 42.2 | 38.6 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 3.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 761 | 430 | 268 | 2.3 | 22.5 | 32.9 | 5.1 | 0.3 |

| Iodine (µg) | 153 | 87.3 | 59.4 | 0.4 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Iron (mg) | 9.6 | 6.5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Sodium (mg) | 2210 | 1827 | 290 | 32.4 | 10.1 | 49.5 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.3 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 25.2 | 17.9 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 25.5 | 17 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Linoleic acid (g) | 8.8 | 5.9 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Alpha linolenic acid (g) | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Long-chain omega 3 fatty acids (mg) | 233.1 | 115.7 | 56.9 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 51.4 |

| Glycaemic Index | 54.8 | 56.1 | 52.3 | 63.2 | 47.1 | 57.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Glycaemic Load | 110 | 76 | 16 | 4.3 | 10.5 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nutrient | Modelled Intakes | Total PFs 1 | MP 2 | PCI 3 | Fruits | Vegetables | Nuts | High-Omega-3 Fish 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy including fibre (kJ) | 7140 | 2555 | 1470 | 245 | 931 | 681 | 788 | 470 |

| Protein (g) | 77.7 | 23.3 | 26.6 | 0.1 | 2.9 | 7.8 | 5.9 | 11.1 |

| Fat (g) | 70.7 | 22.7 | 13 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 16.7 | 7.6 |

| CHO (g) | 169 | 67.8 | 30.6 | 6.8 | 46 | 15.6 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| Sugars (g) | 94.4 | 26.2 | 11.5 | 6.8 | 43.1 | 5.8 | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| Added sugars (g) | 31.1 | 18.6 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Free sugars (g) | 41.4 | 19.3 | 0.7 | 6.8 | 14.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Fibre (g) | 25.7 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 0.0 |

| Alcohol (g) | 4.5 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Retinol equivalents (µg) | 1017 | 172 | 120 | 14.1 | 147 | 537 | 0.9 | 25.9 |

| Total folate equivalents (µg) | 461 | 188 | 72.3 | 0.2 | 87.2 | 90.7 | 21.7 | 0.7 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 3.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Calcium (mg) | 670 | 215 | 268 | 2.3 | 46.4 | 77.2 | 55.9 | 5.1 |

| Iodine (µg) | 125 | 43.7 | 59.4 | 0.4 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 9.6 |

| Iron (mg) | 9.5 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Sodium (mg) | 1404 | 913 | 290 | 32.4 | 20.8 | 116 | 3.6 | 28 |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.0 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 20.4 | 8.9 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 28.9 | 8.5 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 7.9 | 3.1 |

| Linoleic acid (g) | 12.2 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 0.6 |

| Alpha linolenic acid (g) | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Long-chain omega 3 fatty acids (mg) | 1121 | 57.9 | 56.9 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 17.9 | 0.0 | 987 |

| Glycaemic Index | 52.9 | 56.0 | 52.3 | 63.2 | 47.2 | 57.7 | 21.7 | 0.0 |

| Glycaemic Load | 89.5 | 38 | 16 | 4.3 | 21.7 | 9 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habibi, N.; Leemaqz, S.; Louie, J.C.Y.; Wycherley, T.P.; Grieger, J.A. Dietary Strategies to Reduce Triglycerides in Women of Reproductive Age: A Simulation Modelling Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5137. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245137

Habibi N, Leemaqz S, Louie JCY, Wycherley TP, Grieger JA. Dietary Strategies to Reduce Triglycerides in Women of Reproductive Age: A Simulation Modelling Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(24):5137. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245137

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabibi, Nahal, Shalem Leemaqz, Jimmy Chun Yu Louie, Thomas P. Wycherley, and Jessica A. Grieger. 2023. "Dietary Strategies to Reduce Triglycerides in Women of Reproductive Age: A Simulation Modelling Study" Nutrients 15, no. 24: 5137. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245137

APA StyleHabibi, N., Leemaqz, S., Louie, J. C. Y., Wycherley, T. P., & Grieger, J. A. (2023). Dietary Strategies to Reduce Triglycerides in Women of Reproductive Age: A Simulation Modelling Study. Nutrients, 15(24), 5137. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245137