Post-Migration Changes in Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity among Adult Foreign Residents in Niigata Prefecture, Japan: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

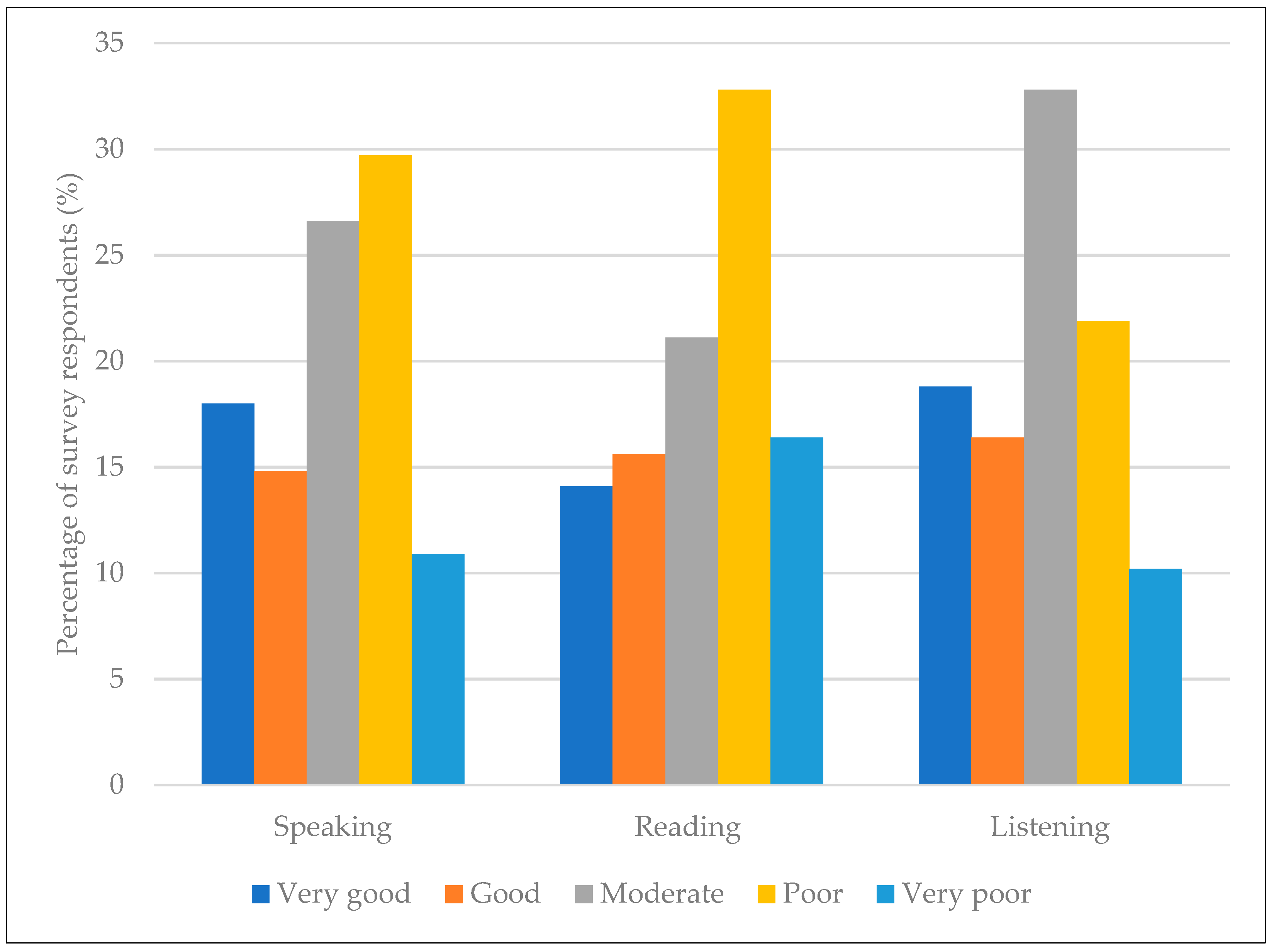

- Demographic, socioeconomic, and cultural data (14 questions on sex, age, country of origin, religious affiliation, years in Japan, education, income, employment, household composition, fluency in the Japanese language, and dietary habits)

- Perceived changes in portion size, food consumption (53 food items), preparation (7 items), and dietary behaviors since immigration (14 items)

- Factors associated with the procurement and preparation of traditional foods (availability, accessibility, and affordability of traditional foods/restaurants) (4 questions)

- Perceived changes in PA behavior since immigration (3 questions)

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Self-Reported Changes in Consumption of Foods/Food Groups

3.3. Self-Reported Changes in Food Preparation Methods and Dietary Behaviors

3.4. Factors Associated with the Procurement and Preparation of Traditional Foods

3.5. Perceived Changes in Physical Activity

3.6. Factors Influencing Post-Migration Dietary Changes: Qualitative Analysis

3.6.1. Environmental Factors

“I just think that everything is more expensive because I got here several months before. Fruits and vegetables here are very expensive. So, when I buy something, I still compare it with the Rupiah (Indonesian Currency).”(Interview #12, Female, Indonesia)

“I eat a lot of chicken here in Japan but not a lot of meat. I mean, like beef. I think it is because of the price. Because first, when I came here, I was just a student. So, at that moment, I saw that the meat was very expensive. Now, I am working and I can afford it, but maybe it became some kind of habit for me.”(Interview #13, Female, Kazakhstan)

Availability and Accessibility of Foods and Ingredients

“After a lot of searching when I first got here, I found the places where I could buy what I needed in Niigata. Like I know exactly where to go if I want pure ground beef rather than mixed pork and beef. There are certain places that sell that. So, when I am preparing local dishes sometimes, I have to get out on the car and go to about 4 to 5 different places to find everything I need. But I know exactly where to go now.”(Interview #5, Male, USA)

“I try to learn some Japanese foods, but my main problem is the language. I mean, when I go to the supermarket, I cannot distinguish well the ingredients. For example, if I find a recipe in English on the internet for Japanese food, I am like, ‘ahh, okay,’ and then I go to the supermarket, and it is difficult for me to find some things. For example, for soy sauce, there are different varieties. So, I cannot understand which one I need.”(Interview #1, Female, Chile)

Food Safety and Related Information

Climate in Niigata

“The weather in Japan, it is very cold for me. The region I live in Indonesia is quite hot, and it’s a tropical country. I think it is easy for me to get hungry here, and I want to eat rice more than I’m in Indonesia. Also, it is so cold in my apartment, so I have to cook something easy and quick, so I just fry it.”(Interview #17, Female, Indonesia)

3.6.2. Individual Factors

Family Structure/Living Status

“I got divorced recently, but when we were living together, we did do the whole, make the broth for two and half hours and do the soup. I don’t have that kind of time right now. When cooking for people, I do a little bit more special, but for myself, no need of it.”(Interview #10, Female, Russia)

Food Preferences and Limitations

“I prefer Chinese food because it’s quite similar to Indonesian food. So, I prefer to go to Chinese restaurants than Japanese restaurants.”(Interview #17, Female, Indonesia)

“I like to explore a lot, and I like to be creative, so sometimes I try to cook something, kinda Mexican style but with Japanese ingredients, I like to try some new stuff, and there are no restrictions. Zero.”(Interview #18, Male, Mexico)

Post-Migration Lifestyle

“I am having Russian style, like lots of vegetable soups, but the bases and broth…it’s like Miso because I don’t have a lot of time to make the broth, I’m just like, Miso is fine. It’s a kind of combing of foods.”(Interview #10, Female, Russia)

3.6.3. Socio-Cultural Factors

Contrast between Traditional and Japanese Food Cultures

“Actually, before coming to Japan, my professors [in India] used to say that if you go to Japan, you should be non-vegetarian. Because, when the professors [in Japan] offer some food, you should not say ‘no.’ It is like a…kind of disrespect. And then I started to eat non-vegetarian food, like 6 or 7 months before coming to Japan.”(Interview #2, Male, India)

Relationships with Japanese People

“Since I use a lot of Japanese in daily life, I have a lot of opportunities to get along with Japanese in general, like connect deeply. And a lot of elders share some secrets or give us some food. So, I think for me, the language opened a lot of doors and a lot of opportunities to try new stuff and get to know a lot of things.”(Interview #18, Male, Mexico)

Religious Influence

3.7. Factors Influencing Changes in PA since Migration: Qualitative Analysis

“There’s a change in physical activity, more physical activity in general. I did start and also stop doing various sports while here [in Japan] as a means of meeting people. So, more physical activity because I am going to places. Even if I lived in another country, this is the same, and this is not something Japan-specific. But I would say riding a bicycle is a Japan-specific thing, and starting sports is not Japan-specific, it’s just a way of meeting people and having a community without too much effort. I got a car last year, so the physical activity kind of dropped, especially in this kind of weather.”(Interview #10, Female, Russia)

3.8. Summary of Changes and Adaptive Behaviors of Diet and PA after Migration

4. Discussion

“I sometimes cook some Japanese food like ‘yaki soba’ or ‘yaki udon’ (fried noodles), something simple like that. Not complicated.”(Interview #14, Female, Türkiye)

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akombi-Inyang, B.; Huda, M.N.; Schutte, A.E.; Macniven, R.; Lin, S.; Rawstorne, P.; Xu, X.; Renzaho, A. The Association between Post-Migration Nutrition and Lifestyle Transition and the Risk of Developing Chronic Diseases among Sub-Saharan African Migrants: A Mixed Method Systematic Review Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.V.; Vyas, A.; Cruickshank, J.K.; Prabhakaran, D.; Hughes, E.; Reddy, K.S.; Mackness, M.I.; Bhatnagar, D.; Durrington, P.N. Impact of migration on coronary heart disease factors: Comparison of Gujaratis in Britain and their contemporaries in villages of origin in India. Atherosclerosis 2006, 185, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, N.; Meyer, H.E.; Kumar, B.N.; Claussen, B.; Hussain, A. High Levels of Cardiovascular Risk Factors among Pakistanis in Norway Compared to Pakistanis in Pakistan. J. Obes. 2011, 2011, 163749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennakoon, S.U.B.; Kumar, B.N.; Nugegoda, D.B.; Meyer, H.E. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors between Sri Lankans living in Kandy and Oslo. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenum, A.K.; Diep, L.M.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Holme, I.M.K.; Kumar, B.N.; Birkeland, K.I. Diabetes susceptibility in ethnic minority groups from Turkey, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan compared with Norwegians: The association with adiposity is strongest for ethnic minority women. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholap, N.; Davies, M.; Patel, K.; Sattar, N.; Khunti, K. T2D and cardiovascular disease in South Asians. Prim Care Diabetes 2011, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Craveiro, I.; Basabe, N.; Gonçalves, L. Mixed methods study protocol to explore acculturation, lifestyles and health of immigrants from the community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries in two Iberian contexts: How to face uncertainties amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satia-Abouta, J.; Patterson, R.E.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Elder, J. Dietary acculturation: Applications to nutrition research and dietetics. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Wandel, M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: A focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 18891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlyck-Romanovsky, M.F.; Huang, T.T.; Ahmed, R.; Echeverria, S.E.; Wyka, K.; Leung, M.M.; Sumner, A.E.; Fuster, M. Intergenerational differences in dietary acculturation among Ghanaian immigrants living in New York City: A qualitative study. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, P.; Jurado, L.F. Dietary Acculturation among Filipino Americans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Kim, J. Dietary acculturation and changes of Central Asian immigrant workers in South Korea by health perception. J. Nutr. Health 2021, 54, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. 2020 Population Census. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/index.html (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- OECD. Obesity Update. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/obesity-update.htm (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Zhang, S.; Tomata, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Tsuduki, T.; Tsuji, I. The Japanese Dietary Pattern Is Associated with Longer Disability-Free Survival Time in the General Elderly Population in the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasakawa Sports Foundation. The 2022 SSF National Sports-Life Survey. Available online: https://www.ssf.or.jp/en/publications/index.html (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Zoellner, J.; Harris, J.E. Mixed-methods research in nutrition and dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, I.Y.; Brener, L.; Asante, A.D.; de Wit, J. Determinants of post-migration changes in dietary and physical activity behaviours and implications for health promotion: Evidence from Australian residents od sub-Saharan African ancestry. Health Promot. J. Austral. 2019, 30 (Suppl. S1), 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D.; Kellow, N.J.; Huggins, C.E.; Choi, T.S.T. How and Why Diets Change Post-Migration: A Qualitative Exploration of Dietary Acculturation among Recent Chinese Immigrants in Australia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A.; Ellinger, S.; Haller, D.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Müller, M.J.; Oberritter, H.; Schulze, M. Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satia, J.A.; Patterson, R.E.; Taylor, V.M.; Cheney, C.L.; Shiu-Thornton, S.; Chitnarong, K.; Kristal, A.R. Use of qualitative methods to study diet, acculturation, and health in Chinese-American women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofink, H.E. The worst of the Bangladeshi and the worst of the British: Exploring eating patterns and practices among British Bangladeshi adolescents in East London. Ethn. Health 2012, 17, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggreen-Clausen, A.; Hseing Pha, S.; Mölsted Alvesson, H.; Andersson, A.; Daivadanam, M. Food environment interactions after migration: A scoping review on low- and middle-income country immigrants in high-income countries. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-K.; Sobal, J.; Frongillo, E.A. Acculturation and dietary practices among Korean Americans. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1999, 99, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermúdez, O.L.I.; Falcón, L.M.; Tucker, K.L. Intake and Food Sources of Macronutrients Among Older Hispanic Adults: Association with Ethnicity Acculturation, and Length of Residence in The United States. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Calogiuri, G.; Rossi, A.; Terragni, L. Physical activity levels and perceived changes in the context of intra-EEA migration: A study on Italian immigrants in Norway. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 689156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey (N = 128) | Interview (N = 21) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 32.6 (8.4) | 33.8 (7.6) | |

| Sex, female | 74 (57.8) | 14 (66.7) | |

| Region | |||

| South America | 5 (3.9) | 2 (9.5) | |

| North America and Caribbean | 9 (7.0) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Africa | 12 (9.4) | 2 (9.5) | |

| South Asia | 20 (15.6) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Southeast and East Asia | 59 (46.1) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Central Asia and Russia | 14 (10.9) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Middle East and Turkey | 6 (4.7) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Australia | 3 (2.3) | 0 | |

| Religion | |||

| Christian/catholic | 35 (27.3) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Buddhist | 24 (18.8) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Islam | 17 (13.3) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Hindu | 7 (5.5) | 0 | |

| No particular religious affiliation | 44 (34.4) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Level of education | |||

| High school or less | 7 (5.5) | 0 | |

| Vocational school/diploma | 4 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Bachelor | 44 (34.4) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Master | 52 (40.6) | 10 (47.6) | |

| PhD or higher | 19 (14.8) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Other | 2 (1.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| No. of years living in Japan, mean (SD) | 5.0 (6.3) | 3.6 (3.0) | |

| Residence status | |||

| Vocational/technical school student | 3 (2.3) | 0 | |

| University student | 82 (64.1) | 13 (61.9) | |

| Employment | 28 (21.9) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Dependent | 8 (6.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Permanent resident | 7 (5.5) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Monthly income | |||

| <100,000 ¥ | 19 (14.8) | 3 (9.5) | |

| 100,000–200,000 ¥ | 76 (59.4) | 13 (61.9) | |

| 200,000–300,000 ¥ | 20 (15.6) | 3 (14.3) | |

| >300,000 ¥ | 13 (10.2) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Not employed | 68 (53.1) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Part-time job/s | 19 (14.8) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Full-time job | 36 (28.1) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Self employed | 5 (3.9) | 0 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried | 75 (58.6) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Married/living together | 51 (39.8) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 2 (1.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Living status in Japan | |||

| Living alone | 85 (66.4) | 14 (66.7) | |

| Living with a partner | 16 (12.5) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Living with a family | 27 (21.1) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Dietary habits 2 | |||

| Vegetarian | 8 (6.3) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Vegan | 4 (3.1) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Halal | 15 (11.7) | 3 (14.3) | |

| No beef | 10 (7.8) | 0 | |

| No pork | 17 (13.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Not any meat | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Nothing particular | 93 (72.7) | 15 (71.4) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Frequency of eating traditional dishes | |||

| Everyday | 28 (21.9) | 2 (9.5) | |

| 4–6 times/week | 21 (16.4) | 2 (9.5) | |

| 1–3 times/week | 32 (25.0) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Occasionally | 29 (22.7) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Rarely | 18 (14.1) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Eat Much Less | No Significant Change | Eat Much More | Do Not Eat at All | Total Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staple foods | ||||||

| Rice | 19 (14.8) | 55 (43.0) | 54 (42.2) | 0 | 73 (57.0) | |

| Bread/bakery products | 24 (18.8) | 53 (41.1) | 51 (39.8) | 0 | 75 (58.6) | |

| Spaghetti/pasta | 26 (20.3) | 50 (39.1) | 46 (35.9) | 6 (4.7) | 72 (56.2) | |

| Noodles | 11 (8.6) | 38 (29.7) | 74 (57.8) | 5 (3.9) | 85 (66.4) | |

| Naan/tortilla | 20 (15.6) | 32 (25.0) | 45 (35.2) | 31 (24.2) | 65 (50.8) | |

| Legumes | ||||||

| Fresh beans/peas | 31 (24.2) | 44 (34.4) | 34 (26.6) | 19 (14.8) | 65 (50.8) | |

| Tofu | 5 (3.9) | 41 (32.0) | 59 (46.1) | 23 (18.0) | 64 (50.0) | |

| Vegetables and fruits | ||||||

| Sweet potatoes | 23 (18.0) | 34 (26.6) | 44 (34.4) | 27 (21.1) | 67 (52.3) | |

| Vegetables | 34 (26.6) | 47 (36.7) | 45 (35.2) | 2 (1.6) | 79 (61.7) | |

| Green leaves | 42 (32.8) | 50 (39.1) | 31 (24.2) | 5 (3.9) | 73 (57.0) | |

| Fruits | 64 (50.0) | 34 (26.6) | 27 (21.1) | 3 (2.3) | 91 (71.1) | |

| Mushrooms | 14 (10.9) | 46 (35.9) | 60 (46.9) | 8 (6.3) | 74 (57.8) | |

| Animal foods | ||||||

| Chicken | 10 (7.8) | 56 (43.8) | 60 (46.9) | 2 (1.6) | 70 (54.7) | |

| Beef | 58 (45.3) | 28 (21.9) | 28 (21.9) | 14 (10.9) | 86 (67.2) | |

| Seafoods | ||||||

| Raw fish | 10 (7.8) | 15 (11.7) | 86 (67.2) | 17 (13.3) | 96 (75.0) | |

| Cooked/baked fish | 22 (17.2) | 40 (31.3) | 58 (45.3) | 8 (6.3) | 80 (62.5) | |

| Seaweed | 10 (7.8) | 26 (20.3) | 77 (60.2) | 15 (11.7) | 87 (68.0) | |

| Seafood | 20 (15.6) | 28 (21.9) | 72 (56.3) | 8 (6.3) | 92 (71.9) | |

| Dairy foods | ||||||

| Cheese | 34 (26.6) | 58 (45.3) | 31 (24.2) | 5 (3.9) | 65 (50.8) | |

| Sweets and snacks | ||||||

| Pies/cakes | 46 (35.9) | 47 (36.7) | 32 (25.0) | 3 (2.3) | 78 (60.9) | |

| Chocolates | 25 (19.5) | 59 (46.1) | 41 (32.0) | 3 (2.3) | 66 (51.5) | |

| Salty snacks | 30 (23.4) | 53 (41.4) | 40 (31.3) | 5 (3.9) | 70 (54.7) | |

| Beverages | ||||||

| Green tea | 10 (7.8) | 36 (28.1) | 75 (58.6) | 7 (5.5) | 85 (66.4) | |

| Fruit juice | 47 (36.7) | 44 (34.4) | 26 (20.3) | 11 (8.6) | 73 (57.0) | |

| Seasoning | ||||||

| Salad dressing | 11 (8.6) | 51 (39.8) | 63 (49.2) | 3 (2.3) | 74 (57.8) | |

| Soy sauce | 13 (10.2) | 38 (29.7) | 76 (59.4) | 1 (0.8) | 89 (69.6) | |

| Miso | 9 (7.0) | 13 (10.2) | 100 (78.1) | 6 (4.7) | 109 (85.1) | |

| Mayonnaise | 15 (11.7) | 54 (42.2) | 50 (39.1) | 9 (7.0) | 65 (50.8) | |

| Sauce mix | 21 (16.4) | 47 (36.7) | 45 (35.2) | 15 (11.7) | 66 (51.6) | |

| Less Often/Decreased | Almost Same | More Often/Increased | Not at All | Total Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation methods | ||||||

| Deep frying | 35 (27.3) | 45 (35.2) | 30 (23.4) | 18 (14.1) | 65 (50.8) | |

| BBQ | 46 (35.9) | 31 (24.2) | 25 (19.5) | 26 (20.3) | 71 (55.5) | |

| Grilling | 43 (33.6) | 33 (25.8) | 29 (22.7) | 23 (18.0) | 72 (56.3) | |

| Microwaving | 6 (4.7) | 28 (21.9) | 85 (66.4) | 9 (7.0) | 91 (71.1) | |

| Dietary behaviors | ||||||

| Homemade meals | 35 (27.3) | 43 (33.6) | 50 (39.1) | 0 | 85 (66.4) | |

| Restaurant meals/dine-out | 37 (28.9) | 33 (25.8) | 54 (42.2) | 4 (3.1) | 91 (71.1) | |

| Takeout | 45 (35.2) | 25 (19.5) | 47 (36.7) | 11 (8.6) | 92 (71.9) | |

| Home delivery | 53 (41.4) | 16 (12.5) | 13 (10.2) | 46 (35.9) | 67 (51.6) | |

| Buffet | 35 (27.3) | 31 (24.2) | 44 (34.4) | 18 (14.1) | 79 (61.7) | |

| Skipping breakfast | 16 (12.5) | 30 (23.4) | 53 (41.4) | 29 (22.7) | 69 (53.9) | |

| Late-night meals | 17 (13.3) | 24 (18.8) | 58 (45.3) | 29 (22.7) | 75 (58.6) | |

| Frozen foods | 18 (14.1) | 32 (25.0) | 69 (53.9) | 9 (7.0) | 87 (68.0) | |

| Organic foods | 48 (37.5) | 52 (40.6) | 18 (14.1) | 10 (7.8) | 68 (51.6) | |

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Availability of traditional food ingredients | ||

| All are commonly available | 8 (6.3) | |

| Many are commonly available | 56 (43.8) | |

| Limited options are available | 63 (49.2) | |

| Not available at all | 1 (0.8) | |

| Affordability of traditional food ingredients | ||

| Expensive, do not usually buy | 47 (36.7) | |

| Regardless of high prices, I usually buy | 51 (39.8) | |

| Affordable | 28 (21.9) | |

| Cheap | 2 (1.6) | |

| Methods of buying traditional food ingredients 1 | ||

| Local shops located in the neighborhood | 42 (32.8) | |

| International shops located within Niigata prefecture | 73 (57.0) | |

| Online orders within Japan | 76 (59.4) | |

| Online orders (international) | 25 (19.5) | |

| Sent by family members from the home country | 43 (33.6) | |

| Do not buy at all | 12 (9.4) | |

| Availability of traditional restaurants | ||

| There are many, I usually go | 4 (3.1) | |

| There are some, I usually go | 13 (10.2) | |

| There are some, I occasionally go | 39 (30.5) | |

| There are none | 72 (56.3) | |

| Less Often/Decreased | Almost Same | More Often/Increased | Not at All | Total Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household chores | 10 (7.8) | 43 (33.6) | 71 (55.5) | 4 (3.1) | 81 (63.3) |

| Gardening | 31 (24.2) | 20 (15.6) | 12 (9.4) | 65 (50.8) | 43 (33.6) |

| Walking | 17 (13.3) | 24 (18.8) | 83 (64.8) | 4 (3.1) | 100 (78.1) |

| Climbing stairs | 16 (12.5) | 39 (30.5) | 64 (50.0) | 9 (7.0) | 80 (62.5) |

| Jogging | 19 (14.8) | 41 (32.0) | 25 (19.5) | 43 (33.6) | 44 (34.3) |

| Cycling | 23 (18.0) | 15 (11.7) | 59 (46.1) | 31 (24.2) | 82 (64.1) |

| Running | 25 (19.5) | 27 (21.1) | 21 (16.4) | 55 (43.0) | 46 (35.9) |

| Workout at home | 21 (16.4) | 41 (32.0) | 25 (19.5) | 41 (32.0) | 46 (35.9) |

| Workout at gym | 17 (13.3) | 21 (16.4) | 18 (14.1) | 72 (56.3) | 35 (27.4) |

| Yoga/Pilates | 12 (9.4) | 19 (14.8) | 8 (6.3) | 89 (69.5) | 20 (15.7) |

| Swimming | 26 (20.3) | 16 (12.5) | 7 (5.5) | 79 (61.7) | 33 (25.8) |

| How? | Why? |

|---|---|

| Changes/adaptive behaviors related to food purchasing | |

| 1. Opt for cheaper foods 2. Purchase only when the prices are lower |

|

| 3. Buying smaller quantities |

|

| 4. Driving to other cities where international stores are available 5. Ordering online |

|

| 6. Buying readily available meals from convenience stores |

|

| 7. Avoid purchasing some products |

|

| 8. Start to procure foods and ingredients |

|

| 9. Choosing foods with similar tastes or qualities to traditional foods |

|

| 10. Checking the ingredients of foods before purchasing |

|

| Changes/adaptive behaviors related to food preparation | |

| 1. Start to prepare own meals |

|

| 2. Prepare simple and non-complicated meals |

|

| 3. Fusion of Japanese and traditional cuisines |

|

| 4. Use of substitute ingredients for unavailable traditional ingredients 5. Ignore the non-availability of ingredients that do not affect the flavor significantly 6. Giving up preparation of some traditional dishes 7. Acquiring the skills to prepare and cook traditional/international dishes independently |

|

| 8. Not preparing foods that are unavailable in the home country |

|

| 9. Bulk food preparation and storing 10. Choosing foods that do not spoil quickly |

|

| Changes/adaptive behaviors related to food intake/dietary habits | |

| 1. Bi-cultural meal patterns (traditional cuisines of the foreign resident, and Japanese cuisines) |

|

| 2. Increased intake of Japanese food 3. Learn about authentic Japanese food culture |

|

| 4. Limited intake of Japanese foods |

|

| 5. Not following meal-associated practices that were enjoyed with the family at the home country (ex: tea time) |

|

| 6. Increased food intake |

|

| 7. Missing meals (breakfast) |

|

| 8. Frequent meals |

|

| 9. Eating healthier/unhealthier than in the home country |

|

| 10. Increased use of frozen foods |

|

| 11. Limiting or reduced opportunities to eat together/eat out |

|

| 12. Pre-migration changes in the diet in preparation for adapting to Japanese (food) culture |

|

| Changes/adaptive behaviors related to PA | |

| 1. Reduced outdoor PA (going out and cardio workouts) |

|

| 2. Opting for indoor PA (weight lifting and push-ups) |

|

| 3. Increased outdoor PA |

|

| 4. Sedentary lifestyle |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abeywickrama, H.M.; Uchiyama, M.; Sakagami, M.; Saitoh, A.; Yokono, T.; Koyama, Y. Post-Migration Changes in Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity among Adult Foreign Residents in Niigata Prefecture, Japan: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163639

Abeywickrama HM, Uchiyama M, Sakagami M, Saitoh A, Yokono T, Koyama Y. Post-Migration Changes in Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity among Adult Foreign Residents in Niigata Prefecture, Japan: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(16):3639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163639

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbeywickrama, Hansani Madushika, Mieko Uchiyama, Momoe Sakagami, Aya Saitoh, Tomoe Yokono, and Yu Koyama. 2023. "Post-Migration Changes in Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity among Adult Foreign Residents in Niigata Prefecture, Japan: A Mixed-Methods Study" Nutrients 15, no. 16: 3639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163639

APA StyleAbeywickrama, H. M., Uchiyama, M., Sakagami, M., Saitoh, A., Yokono, T., & Koyama, Y. (2023). Post-Migration Changes in Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity among Adult Foreign Residents in Niigata Prefecture, Japan: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients, 15(16), 3639. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163639