Abstract

This study aims to identify the background factors and experiences of patients with cancer with eating-related problems who require nutrition counselling. Using a mixed-methods approach, this secondary analysis study was conducted on patients with head and neck, oesophageal, gastric, colorectal, or lung cancers who were receiving outpatient chemotherapy. They completed a questionnaire measuring nutrition impact symptoms, eating-related distress, and quality of life (QOL). Patients who required nutrition counselling were interviewed to identify the specific issues they experienced. We reported on nutritional status and nutrition impact symptoms in a previous study. Of the 151 participants, 42 required nutrition counselling. Background factors associated with nutrition counselling were related to the following psychosocial variables: small number of people in the household, undergoing treatment while working, low QOL, and eating-related distress. Four themes were extracted from the specific issues experienced by patients: motivation for self-management, distress from symptoms, seeking understanding and sympathy, and anxiety and confusion. The desire for nutrition counselling was attributable to ‘anxiety caused by the symptoms’ and ‘confusion about the information on eating’. Healthcare professionals should promote multidisciplinary collaboration after considering the factors associated with the required nutrition counselling to provide nutritional support.

1. Introduction

Chemotherapy causes nutrition impact symptoms (NIS), such as taste disorder, olfactory disorder, and constipation [1,2], and can aggravate pre-existing nutritional issues [3,4]. Studies have shown that 50–80% of patients with advanced cancer experience cachexia, a systemic metabolic disorder characterized by weight loss and loss of skeletal muscle mass, which affects their quality of life (QOL) [5]. Approximately 80% of patients with cancer experience anorexia and weight loss [6]. Moreover, numerous patients with advanced cancer and their family members suffer from eating-related distress (ERD) [7]. Nutritional support has been shown to reduce mortality and improve the QOL of patients with cancer [8]. Preliminary research shows that 77.5% of outpatients receiving chemotherapy need nutrition counselling, the need for which is associated with their QOL [9]. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism recommends nutritional intervention to increase oral intake in cancer patients who can eat but are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition [1]. The provision of clinically assisted nutrition in patients with advanced cancer is individually managed based on evidence-based guidance [10]. Nutritional intervention comprises dietary advice and treatment of symptoms that impair food intake and may include the prescription of oral nutritional supplements or tube feeding [11]; however, nutritional intervention alone does not address psychosocial issues.

In addition to nutritional intervention, some patients may require nutrition counselling, which is not limited to ensuring adequate caloric and protein intake. Diet is related to various contextual factors that affect patients, such as anxiety regarding weight loss [12], building physical strength to fight the disease [13], and the desire to maintain pre-illness lifestyles [14] as much as possible. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the psychosocial factors of patients who require nutritional intervention, in addition to their physical factors. While some studies have explored the views of cancer patients in relation to nutrition support using a mixed-method approach and others have examined specific circumstances in which patients require counselling [15,16], to the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated psychosocial factors related to nutrition counselling. Thus, the two main objectives of the study were to: (i) identify the background factors of patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy who required nutrition counselling, and (ii) elucidate specific eating-related problems that these patients wished to discuss in counselling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This is a secondary analysis of a survey study on the needs of cancer patients undergoing outpatient chemotherapy for nutritional counselling [9]. The survey was conducted between August 2016 and November 2017, when patients visited an urban university hospital for chemotherapy in Japan. The investigator waited in the chemotherapy room for seven hours a day. Subsequently, they requested all patients who received chemotherapy as outpatients at the hospital and met the eligibility criteria to participate in the study. Those who were willing to participate were included in the survey. The participant inclusion criteria were: (i) aged 20–80 years with a head and neck, oesophageal, stomach, colorectal, or lung cancer diagnosis, who had never received nutrition counselling during chemotherapy; (ii) undergoing outpatient chemoradiotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, palliative chemotherapy, or targeted treatment; and (iii) willing to participate in the research and provide consent. Patients with severe dementia/mental disorders and those deemed by a doctor as unable to participate owing to psychological/physical reasons were excluded. The patients were given the questionnaire during chemotherapy, which lasted for three to seven hours; this provided sufficient time to complete the survey.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The Institutional Review Board of the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (no. M2015-578) approved this study. The survey began after registering this study as a clinical trial (UMIN registration no. 000021540). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

2.3. Study Design

In this study, we qualitatively analyzed patients’ expressed preferences for nutrition counselling to identify the specific topics they wished to discuss. In our previous investigation, we took anthropometric measurements of the participants (body mass index [BMI], muscle mass, body fat percentage, estimated bone mass, and body water content) using bioelectrical impedance analysis. Then, participants completed a questionnaire to assess NIS, QOL, and ERD. Their albumin level, C-reactive protein level, and modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS, a measure of cachexia based on the sum of albumin and C-reactive protein levels) were determined based on their medical records. While our previous study reported associations with QOL, nutritional status, and ERD [9], the content of the interview has not been reported. This secondary analysis was based on a qualitative analysis of the content of interviews with patients, summarized using a mixed-methods approach.

Patients who answered “yes” to the question “Do you want nutrition counselling?” were included in the study and interviewed to determine what specific issues they would like to discuss. Two individual nutritional consultations with a registered dietitian specializing in cancer were scheduled at one-month intervals, which is the standard in Japan. All surveys, measurements, interviews, and nutrition counselling sessions were scheduled for the same days the participants had outpatient chemotherapy. During the nutrition counselling, the patients’ food intake frequency and activities of daily living were assessed, and advice was given on food quantity, nutritional quality, energy balance, and how to manage the side effects of chemotherapy.

2.4. Questionnaires

The Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment Short Form (PG-SGA SF) was used to measure NIS [17]. The PG-SGA SF scores were calculated based on its manual and a high score indicated more severe nutritional problems. Each item on the PG-SGA SF questionnaire covers patients with weight loss, anorexia, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, thirst, dysgeusia, olfactory disorder, vomiting, dysphagia, early satiety, fatigue, or pain.

Patients’ experience of ERD was assessed using the ERD questionnaire [18] comprising 19 items on distress originating from the patients’ own feelings (ERD-1), concerns regarding information about the patients’ diet (ERD-2), and the relationship between patients and their family members (ERD-3). The participants’ responses were based on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (‘No’) to 4 (‘Always’) (Table A1).

QOL was measured using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ) C30 [19]. This questionnaire measures the global health domain and the physical functioning domain; the items were role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, and symptom scales. A high score on the functional scale represents a high/healthy level of functioning, a high score on the global health status/QOL scale represents a high QOL, and a high score on the symptom scale/item represents a high level of symptomatology/problems.

Social factors were determined through questions regarding education level, marital status, the number of people in the household, employment status, monthly food expenses, and information about who prepares meals.

2.5. Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants who required nutrition counselling. They were asked the following questions: (i) Do you think nutrition counselling is necessary for chemotherapy treatment? (ii) Do you require nutrition counselling from a dietician now? (iii) What do you wish to discuss during nutrition counselling? The interview questions were designed to elicit descriptive responses from the participants. The interviewer transcribed participants’ responses on a survey form. To interpret the concepts behind the answers, they were encoded and categorized using Krippendorff’s content analysis method [20]. Content analysis views data as representations, not of physical events but of texts and expressions that are created to be seen, read, interpreted, and acted on based on their meaning.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Background factors influencing nutrition counselling were analyzed using logistic regression analysis (maximum likelihood estimation). The dependent variable was whether the participant required nutrition counselling. The independent variables were age, QOL, PG-SGA SF score, employment status (yes vs. no), number of people in the household (two or fewer vs. three or more), meal preparation (self vs. someone else), food expenses (25,000 yen)/month or more vs. under 25,000 yen (in Japan, the mean cost of food per person is approximately 25,000 yen), and ERD 1–3 score. SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used, and statistical significance was set at 5%.

For the interview data, content analysis was conducted based on Krippendorff’s guidelines [20]. The interview content was encoded, and statements with similar meanings were organized into conceptual categories. To ensure reliability, content analysis was performed independently by two researchers who had experience in content research and clinical experience in the field of palliative care. Two palliative care specialists supervised the analysis. The qualitative analysis results were integrated with quantitative data as a mixed-methods design [15,16].

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

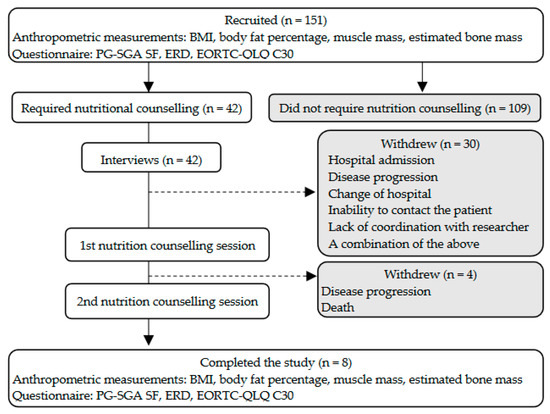

Figure 1 shows the overall research plan. The present qualitative analysis was conducted on the data obtained from the interviews with patients. Table 1 illustrates the patients’ characteristics. Of the 151 patients, 42 (27.8%) required nutrition counselling. There was no significant effect of sex, performance status, cancer site, or BMI on whether patients required nutrition counselling. Of the 42 patients who required nutrition counselling, only 8 (19.0%) completed both sessions. Patients dropped out of the study owing to death, transfer to another hospital, deterioration of their medical condition, loss of contact, and lack of coordination with the researcher.

Figure 1.

Research plan and participants’ BMI, body mass index; EORTC-QLQ C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Version 3.0; ERD, eating-related distress; PG-SGA SF, Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment Short Form.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who required nutrition counselling.

This secondary analysis reports the content and background factors obtained through the interviews with 42 patients, which were conducted prior to the nutritional counselling.

3.2. Psychosocial Factors That Influenced Patients’ Requirements for Nutrition Counselling

Table 2 illustrates the factors that influenced the nutrition counselling requirements of 42 patients using logistic regression analysis. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The coefficient omnibus test model assured the significance of the regression equation (p < 0.001). Hosmer–Lemeshow test significance was p = 0.178, indicating that the prediction accuracy was high. The discrimination accuracy of this logistic regression analysis was 78.7%. Sex, performance status, cancer site, disease stage, BMI, albumin level, C-reactive protein level, mGPS, and individual symptoms were not significantly associated with patients’ nutrition counselling requirement. However, having few members in the household (p = 0.014), working while undergoing treatment (p = 0.015), having low QOL (p = 0.023), and experiencing distress owing to concerns about diet information (ERD-2 score, p = 0.036) were all significantly associated with patients requiring nutrition counselling. The education level and marital status questionnaire items could not be analyzed owing to the large number of unanswered questions pertaining to these items.

Table 2.

Psychosocial factors that influenced nutrition counselling requirements.

3.3. Specific Issues That Led to a Desire for Nutrition Counselling

Table 3 shows the specific issues that 24 participants wished to discuss during nutrition counselling from experiences of eating-related problems. The content analysis revealed the following conceptual categories:

Table 3.

Specific issues patients desired to discuss during nutrition counselling (n = 42).

- (1)

- Motivation for self-management: The participants regarded information about nutrition and diet positively, relating it to their treatment and physical condition.

- (2)

- Distress from symptoms: The participants struggled with nutrition and diet as they dealt with NIS, side effects of chemotherapy, and complications related to other symptoms.

- (3)

- Seeking understanding and sympathy: The participants felt that people around them needed to understand that they were trying to manage food intake levels and NIS.

- (4)

- Anxiety and confusion: The participants were confused and swayed by unclear information owing to their fear of not being able to eat.

Among the participants who took part in nutrition counselling, ‘distress from symptoms’ and ‘information regarding nutritional balance’ were the most common topics they wanted to discuss.

4. Discussion

This study identified the psychosocial factors related to patients with cancer who require nutrition counselling and the specific issues they wished to discuss from their experiences of eating-related problems. The results revealed that the patients believed that diet helps relieve NIS and improve physical health. In contrast, they experienced nutrition-related distress owing to NIS and did not have enough reliable information about nutrition. This led to anxiety about the side effects of chemotherapy and confusion about how to deal with the NIS. Therefore, individual nutrition counselling and specialist information should be provided to patients to help combat nutrition-related distress and confusion [21]. Some studies suggest that dietitians may serve to protect patients against potentially harmful dietary supplement use, fad diets, and other unproven or extreme diets. It is reported that up to 48% of patients with cancer pursue, or are interested in, ‘fad’ or popular diets [22]. The existing literature has shown that nutrition support has the potential to reduce nutritional risk during cancer treatment and address eating problems, and optimal management could improve treatment tolerance and decrease treatment interruptions. Previous reports are consistent with the findings of our study; for example, Hopkinson reported that support for self-management of nutritional risk may protect against malnutrition and be an important aspect of multimodal therapies to arrest the progression of cachexia [23]. Additionally, Arends established that therapeutic options comprise counselling, oral nutritional supplements, enteral and parenteral nutrition, metabolic modulation [21], exercise training, and supportive care to enable and improve the intake of adequate amounts of food, and psycho-oncology and social support [1]. Cancer patients who are affected psychosocially due to reduced eating ability need care from professionals [24].

This study showed that most patients who required nutrition counselling lived alone or with one other person, continued working while undergoing chemotherapy treatment, and had a low QOL (Table 2). Additionally, previous studies have reported a link between poor appetite, anxiety, depression, and loneliness following cancer therapy [25,26]. The results of these studies imply that patients might face difficulties in managing both work and treatment and might want their colleagues and dieticians to understand their symptoms and empathize with their efforts. Alternatively, patients may want to confirm correct information and eliminate anxiety. Ultimately, the desire for nutrition counselling emerged more because of the influence of ‘anxiety caused by the symptoms’ and ‘confusion about information on eating’. Since this study highlighted patients’ state of confusion caused by being overwhelmed with unclear information about food, the impact of dietary information spread through social networks should be further investigated. Online sources reported a conceptual framework of cancer-related nutrition misinformation [27]. Socializing and gathering at mealtimes play an important role in maintaining a psychological balance that contributes to overall QOL and is closely associated with social contact [28]. Therefore, it is imperative to provide psychosocial support for patients who require nutrition counselling. As shown in Table 3, if a patient is unable to eat because of anxiety over future events, specific ways to deal with NIS should be recommended to them. Furthermore, healthcare professionals should consider their issues related to family relationships and help nurture sustained feelings of hope and well-being. Additionally, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy should be encouraged to share valuable moments with friends and family to reduce diet-associated psychosocial distress [29,30]. It is important to empathize with patients’ anxiety about lack of appetite and weight loss and help manage their feelings of remorse for not being able to meet family expectations. This attitude seems to change during the patients’ illness trajectory. Previous findings indicated that patients’ eating deficiencies caused hesitancy about attending social gatherings and led to complete avoidance of such situations. This made them feel lonely and separated from the life they had lived as healthy people [30].

The results of this study show that the need for nutrition counselling is related to psychosocial factors such as living situation, employment status, and psychosocial outcomes, including anxiety and confusion regarding NIS and diet. Nutritional support for patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy requires nutritionists to collaborate with attending physicians, psycho-oncologists, nurses, pharmacists, clinical psychologists, social workers, and physical therapists while sharing relevant information with each other and the patients. Therefore, a multidimensional approach is recommended to support individuals experiencing nutritional issues [21]. Based on this study’s results, we recommend that nutritional screening to determine nutritional status should incorporate psychosocial assessment for ERD and other nutritional issues in addition to conventional assessments, including symptoms and blood test findings. Nutrition counselling is typically conducted by a dietician, but if psychosocial problems are identified, counselling sessions should be set up with a psychologist, a nurse specializing in cancer care, or a psycho-oncologist in addition to a dietician. Furthermore, dietitians should develop skills related to psycho-oncology, particularly related to an understanding that patients often experience anxiety and desperation about not being able or not knowing what to eat. Thus, combination therapy and multimodal care are likely to be critical in nutrition counselling [22,31,32,33,34].

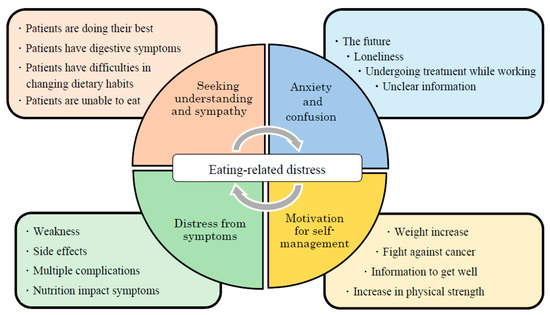

Many patients with advanced cancer undergoing chemotherapy are anxious about their future. Figure 2 illustrates themes of psychosocial and physical support associated with ERD. Therefore, as part of a holistic treatment approach, dieticians should collaborate with specialists in relevant fields to develop multidisciplinary interventions. Furthermore, rather than merely insisting that patients follow their instructions, medical professionals should consider both the symptoms and emotions of patients. Future studies could explore patients’ involvement in decision-making processes regarding what nutritional treatment to choose and how they can adhere to such treatment. A patient may want to adhere to nutritional treatment but be unable to do so because of a debilitating condition. Given such eventualities, the medical staff should ensure that nutrition interventions consider such information and support patients accordingly.

Figure 2.

Themes of psychosocial and physical support associated with eating-related distress.

Based on objective assessments combining NIS, nutritional status, and other relevant data, the qualitative summary of patients’ statements included in this study helped identify their experiences and circumstances. Thus, to develop realistic nutritional support, dieticians should perform assessments from a multifaceted perspective as part of nutrition counselling. Furthermore, to assess the real situation in clinical practice, it is useful to employ a mixed-methods design that combines qualitative assessments of the patients’ subjective data and a quantitative analysis to objectively evaluate their conditions.

This study had the following limitations. First, only eight participants completed the two nutrition counselling sessions. High dropout rates are consistent with advanced cancer, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines stated that many studies reported high rates of patient dropout, and the difficulty of interventional studies for patients with advanced cancer is a common issue in the field [22]. Future studies should include a larger and more representative sample to better reflect the population. Second, this study has limited generalizability, as all the participants were recruited from one hospital and one nationality. Therefore, future studies should be conducted in other hospitals (e.g., in rural locations, in different countries) to examine whether different participant groups yield similar results. Further cohort studies are needed to investigate the impact of improved nutritional status on survival, chemotherapy side effects, and motivation for treatment, and to determine what type of nutrition counselling is effective.

5. Conclusions

This study elucidated the psychosocial factors of patients who require nutrition counselling and the specific issues they wished to discuss. The results showed that patients who required nutrition counselling tended to live with fewer people, had low QOL, and were working during treatment. They often experienced distress originating from concerns regarding their diet. Four themes were extracted using content analysis regarding the specific issues that patients who require nutrition counselling wished to discuss: (i) motivation for self-management, (ii) distress from symptoms, (iii) seeking understanding and sympathy, and (iv) anxiety and confusion. Ultimately, the desire for nutrition counselling emerged mostly because of the influence of ‘anxiety caused by the symptoms’ and ‘confusion about information on eating’. Therefore, multidisciplinary support related to nutritional symptoms, and psychological (anxiety, confusion) and social (household structure, employment situation) factors may help cancer patients undergoing outpatient chemotherapy to enhance their QOL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and E.M.; methodology, S.K., T.Y., K.A. and E.M.; validation, T.Y. and J.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K., M.A., K.S. and A.H.; resources, S.K.; data curation, S.K., T.Y., J.K. and K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, T.T. and E.M.; supervision, T.T. and E.M.; project administration, E.M.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Nestle Nutritional Council and Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (no. M2015-578). The survey began after registering this study as a clinical trial (UMIN registration no. 000021540).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all the patients who kindly participated in this study despite undergoing cancer treatment. We also wish to thank the nurses and dieticians who kindly supported this study and the doctors who provided valuable advice. A preprint has previously been published [35].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire items of eating-related distress (ERD) for cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items of eating-related distress (ERD) for cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.

| Question Items | Likert Scale | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distress originating from the feelings of patients themselves (ERD-1) | No | Sometimes | Frequently | Always |

| I feel that lack of nutrition makes my condition worse. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I think that I cannot eat because of a lack of effort on my part. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I feel that it is the natural course of the disease that I cannot get enough nutrition and that I lose weight. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I am disappointed to find that I cannot eat enough. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I feel that I should make efforts to get enough nutrition even if I have a bad physical condition. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Distress originating from concerns regarding information about the patient’s diet (ERD-2) | No | Sometimes | Frequently | Always |

| I think that losing weight results from a lack of nutrition and that I can gain weight if I get enough nutrition. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I have eaten what I want without consideration of calories and nutritional composition. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I have made myself concerned about my daily diet. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I have tried to eat various foods. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I have tried to eat a high-calorie and well-balanced diet. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I have found it useless to consult medical staff about my daily diet. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I would like to consult an expert who has specific knowledge of nutrition therapy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Distress originating from the relationship between patients and their families (ERD-3) | No | Sometimes | Frequently | Always |

| I am burdened by meals that are made for me with kindness. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I often experience conflict about meals when a person makes them for me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I feel that I disregard the kindness of the person who makes meals for me when I cannot eat. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I try to have a good meal not for myself but for family members. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I avoid talking about food and eating with family members. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Although family members and friends recommend various foods to me, I am just confused. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I often feel that I am forced to eat. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Participants responded on a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (no) to 4 (always).

Table A2.

Comparison of characteristics before and after nutrition counselling (n = 8).

Table A2.

Comparison of characteristics before and after nutrition counselling (n = 8).

| Variable | Nutrition Counselling | p Value § | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age | 70.6 ± 5.9 | 70.6 ± 5.9 | - |

| Cancer Stage (median) | III | III | - |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.6 ± 2.1 | 20.5 ± 1.9 | 0.833 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 0.018 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 1.0 | 0.063 |

| mGPS | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.317 |

| PG-SGA SF Score | 7.3 ± 4.0 | 7.4 ± 4.3 | 1.000 |

| QOL (EORTC-QLQ C30) | |||

| Global Health Status | 58.3 ± 13.4 | 59.4 ± 21.5 | 0.854 |

| Physical Functioning | 82.5 ± 10.0 | 85.0 ± 7.8 | 0.461 |

| Role Functioning | 77.1 ± 21.7 | 87.5 ± 19.4 | 0.102 |

| Emotional Functioning | 85.4 ± 13.9 | 88.6 ± 11.7 | 0.581 |

| Cognitive Functioning | 91.7 ± 17.8 | 91.7 ± 17.8 | 1.000 |

| Social Functioning | 83.3 ± 21.8 | 91.7 ± 17.8 | 0.180 |

| Dyspnoea | 37.5 ± 21.4 | 29.1 ± 11.8 | 0.157 |

| Sleep Disorder | 16.7 ± 17.8 | 16.7 ± 25.2 | 0.705 |

| Poor Appetite | 29.2 ± 27.8 | 29.2 ± 27.8 | 1.000 |

| Diarrhea | 16.7 ± 35.4 | 12.5 ± 35.4 | 0.655 |

| Constipation | 20.8 ± 30.9 | 20.8 ± 24.8 | 1.000 |

| Pain | 20.8 ± 14.8 | 16.7 ± 17.8 | 0.715 |

| Fatigue | 47.2 ± 26.4 | 29.2 ± 23.0 | 0.042 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 4.2 ± 7.7 | 2.1 ± 5.9 | 0.317 |

| Financial Problems | 12.5 ± 24.8 | 4.2 ± 11.8 | 0.180 |

Alb, serum albumin; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; EORTC-QLQ C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Version 3.0; mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; PG-SGA-SF, Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment-Short Form; QOL, quality of life; and SD, standard deviation. § Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table A3.

Relationship between eating-related distress and nutrition counselling (n = 8).

Table A3.

Relationship between eating-related distress and nutrition counselling (n = 8).

| Question Items | Nutrition Counselling | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Distress originating from the feelings of patients themselves (ERD-1) | before † | after † | p value § |

| I feel that lack of nutrition makes my condition worse. | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.000 |

| I think that I cannot eat because of a lack of effort on my part. | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.157 |

| I feel that it is the natural course of the disease that I cannot get enough nutrition and that I lose weight. | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.000 |

| I am disappointed to find that I cannot eat enough. | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.000 |

| I feel that I should make efforts to get enough nutrition even if I have a bad physical condition. | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.680 |

| Distress originating from concerns regarding information about the patient’s diet (ERD-2) | before † | after † | p value § |

| I think that losing weight results from a lack of nutrition and that I can gain weight if I get enough nutrition. | 1.9 | 2.4 | 0.357 |

| I have eaten what I want without consideration of calories and nutritional composition. | 1.4 | 2.0 | 0.180 |

| I have made myself concerned about my daily diet. | 3.4 | 2.5 | 0.102 |

| I have tried to eat various foods. | 3.9 | 3.8 | 0.317 |

| I have tried to eat a high-calorie and well-balanced diet. | 3.4 | 3.4 | 1.000 |

| I have found it useless to consult medical staff about my daily diet. | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.317 |

| I would like to consult an expert who has specific knowledge on nutrition therapy. | 2.9 | 2.4 | 0.336 |

| Distress originating from the relationship between patients and their families (ERD-3) | before † | after † | p value § |

| I am burdened by meals that are made for me with kindness. | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.317 |

| I often experience conflict about meals when a person makes them for me. | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.564 |

| I feel that I disregard the kindness of the person who makes meals for me when I cannot eat. | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.000 |

| I try to have a good meal not for myself but for family members. | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.000 |

| I avoid talking about food and eating with family members. | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.317 |

| Although family members and friends recommend various foods to me, I am just confused. | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.025 |

| I often feel that I am forced to eat. | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.317 |

ERD, eating-related distress. † Mean values: 1 = no, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = always. § Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

References

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omlin, A.; Blum, D.; Wierecky, J.; Haile, S.R.; Ottery, F.D.; Strasser, F. Nutrition impact symptoms in advanced cancer patients: Frequency and specific interventions, a case-control study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, K.; Satomi, E.; Oyamada, S.; Ishiki, H.; Sakashita, A.; Miura, T.; Maeda, I.; Hatano, Y.; Yamauchi, T.; Oya, K.; et al. The prevalence of artificially administered nutrition and hydration in different age groups among patients with advanced cancer admitted to palliative care units. Clin. Nutr. Open. Sci. 2021, 40, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, V.; Bagnasco, A.; Aleo, G.; Catania, G.; Zanini, M.P.; Timmins, F.; Sasso, L. The life experience of nutrition impact symptoms during treatment for head and neck cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasvis, P.; Vigano, M.; Vigano, A. Health-related quality of life across cancer cachexia stages. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracos, V.E. Cancer-associated malnutrition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, K.; Morita, T.; Koshimoto, S.; Uno, T.; Katayama, H.; Tatara, R. Eating-related distress in advanced cancer patients with cachexia and family members: A survey in palliative and supportive care settings. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargetzi, L.; Brack, C.; Herrmann, J.; Bargetzi, A.; Hersberger, L.; Bargetzi, M.; Kaegi-Braun, N.; Tribolet, P.; Gomes, F.; Hoess, C.; et al. Nutritional support during the hospital stay reduces mortality in patients with different types of cancers: Secondary analysis of a prospective randomized trial. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimoto, S.; Arimoto, M.; Saitou, K.; Uchibori, M.; Hashizume, A.; Honda, A.; Amano, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Uetake, H.; Matsushima, E. Need and demand for nutritional counselling and their association with quality of life, nutritional status and eating-related distress among patients with cancer receiving outpatient chemotherapy: A cross-sectional study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3385–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, B.; Allan, L.; Amano, K.; Bouleuc, C.; Davis, M.; Lister-Flynn, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Davies, A. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) expert opinion/guidance on the use of clinically assisted nutrition in patients with advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 2983–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.; van der Lugt, C.; Leermakers-Vermeer, M.J.; de Roos, N.M.; Speksnijder, C.M.; de Bree, R. Nutritional interventions in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy: Current practice at the Dutch Head and Neck Oncology centres. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, F.E.; Jansen, F.; Mak, L.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Buter, J.; Vergeer, M.R.; Voortman, J.; Cuijpers, P.; Leemans, C.R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. The course of symptoms of anxiety and depression from time of diagnosis up to 2 years follow-up in head and neck cancer patients treated with primary (chemo)radiation. Oral Oncol. 2020, 102, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, L.; Kober, K.M.; Viele, C.; Cooper, B.A.; Paul, S.M.; Conley, Y.P.; Hammer, M.; Levine, J.D.; Miaskowski, C. Subgroups of patients undergoing chemotherapy with distinct cognitive fatigue and evening physical fatigue profiles. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7985–7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kruif, A.J.; Westerman, M.J.; Winkels, R.M.; Koster, M.S.; van der Staaij, I.M.; van den Berg, M.M.G.A.; de Vries, J.H.M.; de Boer, M.R.; Kampman, E.; Visser, M. Exploring changes in dietary intake, physical activity and body weight during chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganzer, H.; Rothpletz-Puglia, P.; Byham-Gray, L.; Murphy, B.A.; Touger-Decker, R. The eating experience in long-term survivors of head and neck cancer: A mixed-methods study. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3257–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeliger, J.; Dewar, S.; Kiss, N.; Drosdowsky, A.; Stewart, J. Patient and carer experiences of nutrition in cancer care: A mixed-methods study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5475–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.; Teleni, L.; McKavanagh, D.; Watson, J.; McCarthy, A.L.; Isenring, E. Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment Short Form (PG-SGA SF) is a valid screening tool in chemotherapy outpatients. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3883–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, K.; Morita, T.; Miyashita, M. Potential measurement properties of a questionnaire for eating-related distress among advanced cancer patients with cachexia: Preliminary findings of reliability and validity analysis. J. Palliat. Care 2022, 37, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, C.F.; Blackford, A.L.; Sussman, J.; Bainbridge, D.; Howell, D.; Seow, H.Y.; Carducci, M.A.; Wu, A.W. Identifying changes in scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 representing a change in patients’ supportive care needs. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Arends, J. Struggling with nutrition in patients with advanced cancer: Nutrition and nourishment—Focusing on metabolism and supportive care. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, ii27–ii34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, E.J.; Bohlke, K.; Baracos, V.E.; Bruera, E.; del Fabbro, E.; Dixon, S.; Fallon, M.; Herrstedt, J.; Lau, H.; Platek, M.; et al. Management of cancer cachexia: ASCO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2438–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J. Psychosocial impact of cancer cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lize, N.; IJmker-Hemink, V.; van Lieshout, R.; Wijnholds-Roeters, Y.; van den Berg, M.; Soud, M.Y.-E.; Beijer, S.; Raijmakers, N. Experiences of patients with cancer with information and support for psychosocial consequences of reduced ability to eat: A qualitative interview study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6343–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenne, E.; Loge, J.H.; Kaasa, S.; Heitzer, E.; Knudsen, A.K.; Wasteson, E. Depressed patients with incurable cancer: Which depressive symptoms do they experience? Palliat. Support. Care 2013, 11, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıracı, Y.; Nural, N.; Saltürk, Z. Loneliness of oncology patients at the end of life. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3525–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, E.L.; Basen-Engquist, K.M.; Badger, T.A.; Crane, T.E.; Raber-Ramsey, M. The Online Cancer Nutrition Misinformation: A framework of behavior change based on exposure to cancer nutrition misinformation. Cancer 2022, 128, 2540–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, G.V. Psychological aspects of nutrition and cancer. Nutr. Cancer II 1986, 66, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuestion, M.; Fitch, M.; Howell, D. The changed meaning of food: Physical, social and emotional loss for patients having received radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, V.; Carlander, I.; Sandman, P.-O.; Håkanson, C. Meanings of eating deficiencies for people admitted to palliative home care. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Fabbro, E. Combination therapy in cachexia. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2019, 8, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J. Psychosocial support in cancer cachexia syndrome: The evidence for supported self-management of eating problems during radiotherapy or chemotherapy treatment. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 5, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, J.B.; Kazmi, C.; Elias, J.; Wheelwright, S.; Williams, R.; Russell, A.; Shaw, C. Diet and weight management by people with nonmetastatic colorectal cancer during chemotherapy: Mixed methods research. Color. Cancer 2020, 9, CRC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Hopkinson, J.; Conibear, J.; Reeves, A.; Shaw, C.; Fearon, K.C.H. Practical multimodal care for cancer cachexia. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 10, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshimoto, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Amano, K.; Kako, J.; Arimoto, M.; Saitou, K.; Hashizume, A.; Takeuchi, T.; Matsushima, E. Psychosocial support and nutrition counselling among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: A mixed-methods study. Resh Sq. 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).