Children’s Participation in Free School Meals: A Qualitative Study among Pupils, Parents, and Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment and Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Popularity of the Food

Int. So, what kind of food is most popular?

The kind of food that is not healthy in a way. Pasta, for instance. But it depends on what kind of sauce you add. And then meat, chicken. The meals with meat are very popular and many come to eat.(Boy, 9th grade, GN1)

Int. Ok, and what is unpopular?

Fish (many laugh) Fish can be good if you mix it with something else. But is never good alone.(Boy, 9th grade, GN1)

I agree that [the classmates] came because of the toast (…) but now it is just ordinary food that you can just as well eat at home.(Boy, 7th grade, GN13)

One day we got just pancakes, and we thought that we were going to get pancakes every day. So, we said to the others: there are pancakes, you have to come! But we were wrong. The next week many came to the breakfast, but there were no pancakes. So they just turned around and went away.(Girl, 6th grade, GN12)

We had a survey, where people should write what they would like to have. Then there came up a lot of pancakes, waffles, smoothie bowls and things like that. (…) We cannot get all our wishes fulfilled (…) because we are not allowed because of Oslo Municipality. They sponsor us with healthy food, or we have to buy healthy food. (…) Yes, and then it will be less popular.(Girl, 10th grade, GN2)

I think a lot of food is thrown away because, for instance, when chicken salad is served, they [the classmates] are eating the chicken. But they do not always eat the salad. Thus, you take the salad because of the chicken.(Boy, 9th grade, GN1)

If they do not like it [the lunch], then they throw it right away. If it tastes bad in any way, they go to the bathroom and throw it away.(Girl, 10th grade, GN2)

As I said to you, cabbage soup that nutritionally would be very good, it would be just you and me who ate it. So, I have to find—you have to find—dishes which appeal to that age group.(Teacher, GN4)

Burgers are usually unhealthy, but today for example, we had wholegrain bread and fish instead of meat.(Boy, 9th grade, GN1)

3.2. Competition with Other Options: The Temptation of the Nearby Shopping Center

Yes, in the autumn of the 8th grade, all the pupils bring a packed lunch. (…) Eh, and then the visits to the center increases as the lunch boxes disappear. Eh, so it is true that the 10th grade has traditionally been a lot at the center. They still do it now, even though they are offered [free] food.(Teacher, GN8)

It really depends on the day, whether it’s a day where you feel like having bread or rather a small meatball, or something like that. Otherwise, it’s a day when you feel like having something sweet and just buy chocolate, you know.(Girl, 10th grade, GN2)

There are a lot of sweet buns and energy drinks. They [the 10th graders] buy it. That’s what they go to the center for buying. And it has something to do with age. They are allowed to buy energy drinks when they have become 10th graders, and then they can buy it. And especially the boys, not so many girls but many boys are buying energy drinks every day.(Teacher, GN8)

I think the older you get in lower-secondary school, the more you want to detach yourself from maybe being a pupil in primary school. (…) I don’t think this is strange—that they try to free themselves more and more from having to eat at school and so on when they become older and when they reach the 10th grade.(Mother, GN5)

3.3. Eating Food Together: The Sociality of Meals at School

I think the breakfast is really good. And I usually attend it. Sometimes I’m also there with lots of friends and stuff, so it’s really fun.(Boy, 7th grade, GN14)

Because in the morning it is, like we as a family we are getting up at different times, so that [the children] often eat breakfast alone. So, therefore, [the children] thought it was all right to eat with someone.(Mother, GN16)

If one or two are sitting and eating food from the canteen, all the other friends will be there as well and sit together. So there are more people in the auditorium. And you hear it very well, and it is more social. And there are fewer who go to the center, I think.(Girl, 9th grade, GN1)

[…] there is a different kind of unity. We notice that. They say that when there is food [for lunch], they stay there. And then they sit there and talk and game instead of going to the center.(Mother, n6, GN6)

But it’s kind of, the young teachers who tend to be at the school breakfast. Yes, it’s a bit; you are allowed to joke a bit with them then.(Boy, 7th-grade, GN14)

Eh, sometimes the principal or some of the teachers come, and then they come and eat with us and talk to us like whether we’re fine and so on.(Girl, 7thgrade, GN13)

Maybe [the classmates] think that if my friend isn’t coming, then I do not bother, and then also the others do not bother to come.(Boy, 7th-grade, GN14)

I think this quickly sort of becomes a bit like part of the culture in a class, you know. I saw that when my eldest did not go [to the school breakfast], I don’t think there was such a large attendance from the whole class at the time. And that it was rather maybe a bunch of girls but none of the boys, and that I think is just a bit like a group mentality then. (…), it is difficult perhaps to turn it around a bit because then it is only defined as not cool somehow.(Mother, n11, GN15)

We have a large group of boys [10th grade] who do not eat in the canteen, period.(Teacher, GN8)

3.4. Predictability and Continuity of the Provided Meals

It may be that they [the classmates] do not remember [the breakfast serving] like me. I often forget it.(Boy, 5th grade, GN11)

Sometimes I have brought a packed lunch with me, that I have forgotten that [food is served in] the canteen and so on, but I usually eat when there is food.(Girl, 9th grade, GN1)

Eh, the challenges are then that [the lunch] is not every day. As I believe (…) that is the predictability. It was discussed that they do not always know what day [lunch is served]. If it had been every day, there would have been more continuity. (…). And then it’s kind of like that it’s safer to bring a packed lunch. Ok, then I know what to eat today. I think he [the son] would have eaten more of the hot food if it had been provided every day. Because there is something about the planning.(Mother, n9, GN7)

No, the days when there is food at school, prior to it, there is a lot of talk about what it will be tomorrow. Should I make a backup packed lunch, or should I not?(Mother, n1, GN5)

If I had known—it is possible I haven’t followed well enough, and I’ve probably not done that. But in terms of pushing my son to attend those meals, I would probably have done it if I had insight into the menu plan and maybe how the food is prepared.(Father, n4, GN6)

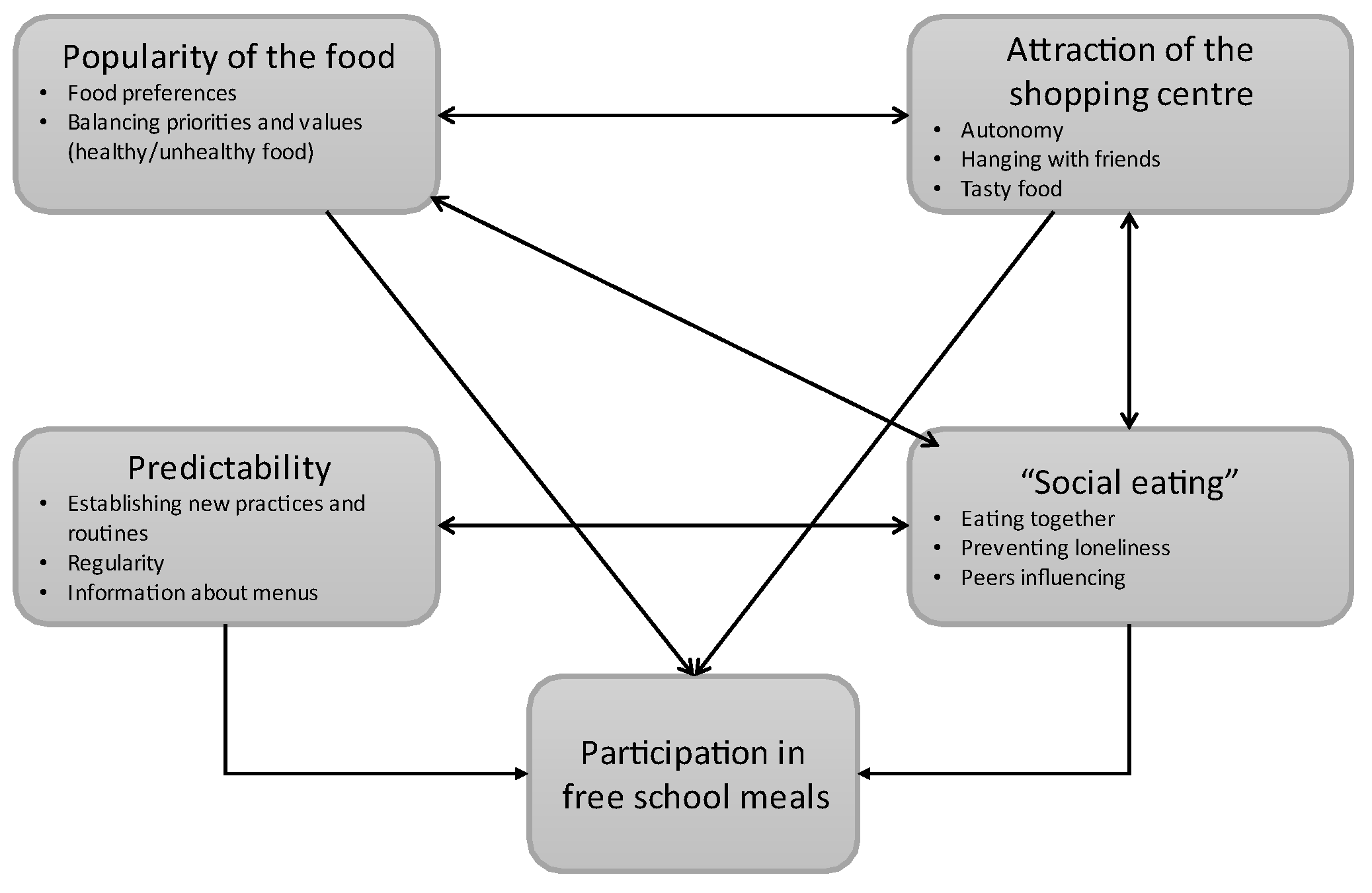

3.5. Conceptual Framework

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, D.; Stewart, D. The implementation and effectiveness of school-based nutrition promotion programmes using a health-promoting schools approach: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1082–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, R.; Bonell, C.; Jones, H.E.; Pouliou, T.; Murphy, S.; Waters, E.; Komro, K.A.; Gibbs, L.; Magnus, D.; Campbell, R. The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torheim, L.E.; Løvhaug, A.L.; Huseby, C.S.; Terragni, L.; Henjum, S.; Roos, G. Sunnere Matomgivelser i Norge. Vurdering av Gjeldende Politikk og Anbefalinger for Videre Innsats. Food-EPI 2020 [Healthier Food Environment in Norway. Assessment of Current Policy and Recommendations for Further Efforts. Food-EPI 2020]; Oslo Metropolitan University: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, T.; Jensberg, H. Kost i Skole og Barnehage og Betydningen for Helse og Læring: En Kunnskapsoversikt [Nutrition in Schools and Kindergartens and the Importance of Health and Learning: An Overview of Current Knowledge]; Nordisk Ministerråd: København, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Waling, M.; Olafsdottir, A.S.; Lagström, H.; Wergedahl, H.; Jonsson, B.; Olsson, C.; Fossgard, E.; Holthe, A.; Talvia, S.; Gunnarsdottir, I.; et al. School meal provision, health, and cognitive function in a Nordic setting—The ProMeal-study: Description of methodology and the Nordic context. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opplysningskontoret for Frukt og Grønt, Helsedirektoratet [Fruit and Vegetable Information Office]. Skolefrukt for Elever i Grunnskolen [School Fruit for Students in Primary and Lower Secondary School]. 2020. Available online: https://skolefrukt.no (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Federici, R.A.; Gjerustad, C.; Vaagland, K.; Larsen, E.H.; Rønsen, E.; Hovdhaugen, E. Spørsmål til Skole-Norge Våren 2017: Analyser og Resultater fra Utdanningsdirektoratets Spørreundersøkelse til Skoler og Skoleeiere [Questions to School-Norway in the Spring of 2017: Analyzes and Results from the Norwegian Directorate of Education’s Survey of Schools and School Owners]; Report No.: 2017:12; Nordisk Institutt for Studier av Innovasjon, Forskning og Utdanning (NIFU) [The Nordic Institute for Studies of Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU)]: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Øvrebø, B.; Bergh, I.H.; Stea, T.H.; Bere, E.; Surén, P.; Magnus, P.M.; Juliusson, P.B.; Wills, A.K. Overweight, obesity, and thinness among a nationally representative sample of Norwegian adolescents and changes from childhood: Associations with sex, region, and population density. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakken, A. Ung i Oslo 2018 [Young in Oslo 2018: A Norwegian Rapport]; NOVA Report 6/18; Oslo Metropolitan University—OsloMet: NOVA [Norwegian Social Research]: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, A. Ungdata. Nasjonale Resultater 2019 [Ungdata. National Results 2019]; Report No.: NOVA Report 9/19; Oslo Metropolitan University—OsloMet: NOVA [Norwegian Social Research]: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, L.B.; Myhre, J.B.; Wetting Johansen, A.M.; Paulsen, M.M.; Andersen, L.F. UNGKOST 3—Landsomfattende Kostholdsundersøkelse Blant Elever i 4. og 8. Klasse i Norge, 2015 [Nationwide Diet Survey among Students in 4th and 8th Grade in Norway—A Norwegian Report]; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, E.; Robson-Wold, C.; Helland, T.; Jåstad, A.; Torsheim, T.; Fismen, A.-S.; Wol, B.; Samdal, O. Barn og Unges Helse og Trivsel: Forekomst og Sosial Ulikhet i Norge og Norden [Health and Wellbeing of Children and Young People: Incidence and Social Inequality in Norway and the Nordic Countries]. Available online: https://www.uib.no/sites/w3.uib.no/files/attachments/hevas_rapport_v10.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Lazzeri, G.; Ahluwalia, N.; Niclasen, B.; Pammolli, A.; Vereecken, C.; Rasmussen, M.; Pedersen, T.P.; Kelly, C. Trends from 2002 to 2010 in Daily Breakfast Consumption and its Socio-Demographic Correlates in Adolescents across 31 Countries Participating in the HBSC study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Research Council of Norway [Norges forskningsråd]. Phenology of the North Calotte [Nettverk for miljølære]. In Sjekk Skolematen [Examine the School Meal]; Report No.: Norwegian report; The Research Council of Norway: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremariam, M.K.; Henjum, S.; Terragni, L.; Torheim, L.E. Correlates of fruit, vegetable, soft drink, and snack intake among adolescents: The ESSENS study. Food & Nutrition Research. 2016, 60, 32512. [Google Scholar]

- Bugge, A.B. Ungdoms Skolematvaner-Refleksjon, Reaksjon Eller Interaksjon? [Adolescents’ School Eating Habits-Reflection, Reaction, or Interaction? A Norwegian Report]; Report No.: Fagrapport Nr.4-2007; Statens Institutt for Forbruksforskning [National Institute for Consumption Research Norway]: Oslo, Norway, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremariam, M.; Henjum, S.; Hurum, E.; Utne, J.; Terragni, L.; Torheim, L. Mediators of the association between parental education and breakfast consumption among adolescents: The ESSENS study. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeie, G.; Sandvær, V.; Grimnes, G. Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in Adolescents from Troms, Norway-The Tromsø Study: Fit Futures. Nutrients 2019, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.; O’shea, M.; Foley-Nolan, C.; McCarthy, M.; Harrington, J.M. Barriers and facilitators to adoption, implementation and sustainment of obesity prevention interventions in schoolchildren—A DEDIPAC case study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, E.; Bergsli, H.; van Der Wel, K.A. Sosial Ulikhet i Helse: En Norsk Kunnskapsoversikt [Social Inequalities in Health: A Norwegian Review]; Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, N.; Bjelland, M.; Bergh, I.; Grydeland, M.; Anderssen, S.; Ommundsen, Y.; Andersen, L.; Henriksen, H.; Randby, J.; Klepp, K.-I. Design of a 20-month comprehensive, multicomponent school-based randomised trial to promote healthy weight development among 11–13 year olds: The HEalth in Adolescents study. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38 (Suppl. 5), 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.W.; Hecht, A.A.; McLoughlin, G.M.; Turner, L.; Schwartz, M.B. Universal School Meals and associations with student participation, attendance, academic performance, diet quality, food security, and body mass index: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bere, E.; Hilsen, M.; Klepp, K.-I. Effect of the nationwide free school fruit scheme in Norway. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bere, E.; te Velde, S.J.; Smastuen, M.C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Klepp, K.I. One year of free school fruit in Norway-7 years of follow-up. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Øverby, N.C.; Klepp, K.I.; Bere, E. Introduction of a school fruit program is associated with reduced frequency of consumption of unhealthy snacks. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, C.; Kristjansdottir, A.G.; Velde, S.J.T.; Lien, N.; Roos, E.; Thorsdottir, I.; Krawinkel, M.; De Almeida, M.D.V.; Papadaki, A.; Ribic, C.H.; et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption in a sample of 11-year-old children in ten European countries—The PRO GREENS cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2436–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vik, F.N.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Øverby, N.C. Free school meals as an approach to reduce health inequalities among 10–12- year-old Norwegian children. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundborg, P.; Rooth, D.-O.; Alex-Petersen, J. Long-term effects of childhood nutrition: Evidence from a school lunch reform. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2021, 89, 876–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norges Bondelag [Norwegian Farmers’ Association]. Skolematprosjektet og Matopplevelser [The School Food Project and Food Experiences]. Norges Bondelag, 2018. [Updated 2 August]. Available online: https://www.bondelaget.no/trondelag/nyheter/skolematprosjekt-og-matopplevelser (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Hordaland Fylkeskommune [Hordaland County Municipality]. Trappar Opp Ordninga med Skulefrukost [Steps up the School Breakfast Scheme]. Hordaland Fylkeskommune, 2018. [Updated 11 April]. Available online: https://www.hordaland.no/nn-NO/nyheitsarkiv/2018/trappar-opp-ordninga-med-skulefrukost/ (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Ask, A.S.; Hernes, S.; Aarek, I.; Vik, F.; Brodahl, C.; Haugen, M. Serving of free school lunch to secondary-school pupils—A pilot study with health implications. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ask, A.S.; Hernes, S.; Aarek, I.; Johannessen, G.; Haugen, M. Changes in dietary pattern in 15 year old adolescents following a 4 month dietary intervention with school breakfast—A pilot study. Nutr. J. 2006, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vik, F.N.; Næss, I.K.; Heslien, K.E.P.; Øverby, N.C. Possible effects of a free, healthy school meal on overall meal frequency among 10–12-year-olds in Norway: The School Meal Project. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vik, F.N.; Heslien, K.E.P.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Øverby, N.C. Effect of a free healthy school meal on fruit, vegetables and unhealthy snacks intake in Norwegian 10- to 12-year-old children. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illøkken, K.E.; Bere, E.; Øverby, N.C.; Høiland, R.; Petersson, K.O.; Vik, F.N. Intervention study on school meal habits in Norwegian 10–12-year-old children. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 45, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolve, C.S.; Helleve, A.; Bere, E. Gratis Skolemat i Ungdomsskolen—Nasjonal Kartlegging av Skolematordninger og Utprøving av Enkel Modell Med et Varmt Måltid. Rapport 2022; Folkehelseinstituttet: Oslo, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish institute for Health and Welfare. Most Children Eat the School Lunch—However, Many Do Not Eat the Salads 2018 [Updated 11 September]. Available online: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/-/most-children-eat-the-school-lunch-however-many-do-not-eat-the-salads (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Bailey-Davis, L.; Virus, A.; McCoy, T.A.; Wojtanowski, A.; Vander Veur, S.S.; Foster, G.D. Middle School Student and Parent Perceptions of Government-Sponsored Free School Breakfast and Consumption: A Qualitative Inquiry in an Urban Setting. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2013, 113, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddingham, S.; Shaw, K.; Van Dam, P.; Bettiol, S. What motivates their food choice? Children are key informants. Appetite 2018, 120, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahota, P.; Woodward, J.; Molinari, R.; Pike, J. Factors influencing take-up of free school meals in primary- and secondary-school children in England. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.M.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Mansouri, T.H.; Gregory, A.M.I.; Barich, R.A.; Hatzinger, L.A.; Leone, L.A.; Temple, J.L. An Ecological Perspective of Food Choice and Eating Autonomy Among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, H.; Ervasti, J.; Oksanen, T.; Pentti, J.; Kouvonen, A.; Halonen, J.I.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Fast-food outlets and grocery stores near school and adolescents’ eating habits and overweight in Finland. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, F.F. En god start på dagen for alle? Sosioøkonomisk ulikhet i frokostvaner blant unge i Oslo. Tidsskr. Velferdsforskning 2020, 23, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Agency for Health in Oslo. Oslohelsa 2020: Oversikt over Påvirkningsfaktorer og Helsetilstand i Oslo [Oslo Health 2020: Overview of Influencing Factors and Health Status in Oslo]; Oslo Kommune Helseetaten: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gotaas, N. Barn, Unge og Utjevning av Sosial Ulikhet i Helse: En kartleggingsundersøkelse av Byomfattende Plandokumenter i Oslo Kommune [Children, Young People and Equalization of Social Inequality in Health: A Survey of City-Wide Planning Documents in Oslo Municipality]; Report NIBR-report 2020:11; NIBR: Cambridge, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, M.; Mehta, K.; Matwiejczyk, L.; Moores, C.J.; Prichard, I.; Mortimer, S.; Bell, L. Treats are a tool of the trade: An exploration of food treats among grandparents who provide informal childcare. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2643–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobal, J.; Nelson, M.K. Commensal eating patterns: A community study. Appetite 2003, 41, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, L.K.B.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernández, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Danvers, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. Consumption and theories of practice. J. Consum. Cult. 2005, 5, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, R.; Van Royen, K.; Ochoa-Avilés, A.; Penafiel, D.; Holdsworth, M.; Donoso, S.; Maes, L.; Kolsteren, P. A conceptual framework for healthy eating behavior in Ecuadorian adolescents: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensaff, H.; Canavon, C.; Crawford, R.; Barker, M.E. A qualitative study of a food intervention in a primary school: Pupils as agents of change. Appetite 2015, 95, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torralba, J.A.T.; Guidalli, B.A. Developing a conceptual framework for understanding children’s eating practices at school. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2014, 21, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Bronwyn, M.; Leonie, C.; Lucy, C.; Margaret, T. School Meal Provision: A Rapid Evidence Review. Prepared for the NSW Ministry of Health: Sydney; Physical Activity Nutrition Obesity Research Group, The University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blondin, S.A.; Djang, H.C.; Metayer, N.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Economos, C.D. ‘It’s just so much waste’. A qualitative investigation of food waste in a universal free School Breakfast Program. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Wang, Q.; Skuland, S.E.; Egelandsdal, B.; Amdam, G.V.; Schjøll, A.; Pachucki, M.C.; Rozin, P.; Stein, J.; et al. Are school meals a viable and sustainable tool to improve the healthiness and sustainability of children’s diet and food consumption? A cross-national comparative perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3942–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinley, M.C.; Lowis, C.; Robson, P.J.; Wallace, J.M.W.; Morrissey, M.; Moran, A.; Livingstone, M.B.E. It’s good to talk: Children’s views on food and nutrition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atik, D.; Ozdamar Ertekin, Z. Children’s perception of food and healthy eating: Dynamics behind their food preferences. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Devine, C.M. Managing values in personal food systems. Appetite 2001, 36, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastran, M.M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Blake, C.; Devine, C.M. Eating routines. Embedded, value based, modifiable, and reflective. Appetite 2009, 52, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, K.; Ferrage, A.; Rytz, A. Involving children in meal preparation. Effects on food intake. Appetite 2014, 79, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defeyter, M.A.; Graham, P.L.; Russo, R. More than Just a Meal: Breakfast Club Attendance and Children’s Social Relationships. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugge, A.B. Lovin’ It? Food Cult. Soc. 2011, 14, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, A.; Osnes, S.M. Ung i Oslo 2021- 5. til 7. trinn; NOVA Report 10/21; Oslo Metropolitan University—OsloMet: NOVA [Norwegian Social Research]: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Illøkken, K.E.; Johannessen, B.; Barker, M.E.; Hardy-Johnson, P.; Øverby, N.C.; Vik, F.N. Free school meals as an opportunity to target social equality, healthy eating, and school functioning: Experiences from students and teachers in Norway. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 65, 7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arntzen, A.; Bøe, T.; Dahl, E.; Drange, N.; Eikemo, T.A.; Elstad, J.I.; Fosse, E.; Krokstad, S.; Syse, A.; Sletten, M.A.; et al. 29 recommendations to combat social inequalities in health. The Norwegian Council on Social Inequalities in Health. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.S.; Holm, L.; Baarts, C. School meal sociality or lunch pack individualism? Using an intervention study to compare the social impacts of school meals and packed lunches from home. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2015, 54, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.S.; Vassard, D.; Havn, L.N.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Holm, L. Measuring the impact of classmates on children’s liking of school meals. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærnes, U.; Døving, R. Controlling Fat and Sugar in the Norwegian Welfare State—A Twentieth Century Food History. In The Rise of Obesity in Europe; Oddy, D.J., Atkins, P.J., Amilien, V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaernes, U.; Holm, L. Social Factors and Food Choice: Consumption as Practice; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bere, E.; Veierød, M.B.; Bjelland, M.; Klepp, K.-I. Outcome and process evaluation of a Norwegian school-randomized fruit and vegetable intervention: Fruits and Vegetables Make the Marks (FVMM). Health Educ. Res. 2005, 21, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruance, L.A.; Harrison, C.; Brady, P.; Woolford, M.; LeBlanc, H. Who Eats School Breakfast? Parent Perceptions of School Breakfast in a State With Very Low Participation. J. Sch. Health 2018, 88, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, C.L.; Brady, P.; Askelson, N.; Ryan, G.; Delger, P.; Scheidel, C. What Do Parents Think About School Meals? An Exploratory Study of Rural Middle School Parents’ Perceptions. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryden-Palmer, K.D.; Parshuram, C.S.; Berta, W.B. Context, complexity and process in the implementation of evidence-based innovation: A realist informed review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory as an emergent method. Handb. Emergent Methods 2008, 155, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Irani, E. The Use of Videoconferencing for Qualitative Interviewing: Opportunities, Challenges, and Considerations. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2019, 28, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Participants Total | Number of Interviews Total | Primary School 5th–7th Grade | Lower-Secondary School 8th–10th Grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Interviews | Participants | Interviews | |||

| Pupils n | 39 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 27 | 3 |

| Boys | 12 | 5 | 7 | |||

| Girls | 27 | 7 | 20 | |||

| Norwegian | 24 | 6 | 18 | |||

| Immigrant | 15 | 6 | 9 | |||

| background | ||||||

| Parents n | 15 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 3 |

| Men | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Women | 13 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Norwegian | 13 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Immigrant | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| background | ||||||

| School staff n | 12 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Men | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Women | 8 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Total | 66 | 20 | 26 | 12 | 40 | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mauer, S.; Torheim, L.E.; Terragni, L. Children’s Participation in Free School Meals: A Qualitative Study among Pupils, Parents, and Teachers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061282

Mauer S, Torheim LE, Terragni L. Children’s Participation in Free School Meals: A Qualitative Study among Pupils, Parents, and Teachers. Nutrients. 2022; 14(6):1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061282

Chicago/Turabian StyleMauer, Sandra, Liv Elin Torheim, and Laura Terragni. 2022. "Children’s Participation in Free School Meals: A Qualitative Study among Pupils, Parents, and Teachers" Nutrients 14, no. 6: 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061282

APA StyleMauer, S., Torheim, L. E., & Terragni, L. (2022). Children’s Participation in Free School Meals: A Qualitative Study among Pupils, Parents, and Teachers. Nutrients, 14(6), 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061282