Abstract

The increase in the availability of processed and ultra-processed foods has altered the eating patterns of populations, and these foods constitute an exposure factor for the development of arterial hypertension. This systematic review analyzed evidence of the association between consumption of processed/ultra-processed foods and arterial hypertension in adults and older people. Electronic searches for relevant articles were performed in the PUBMED, EMBASE and LILACS databases. The review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. The search of the databases led to the retrieval of 2323 articles, eight of which were included in the review. A positive association was found between the consumption of ultra-processed foods and blood pressure/arterial hypertension, whereas insufficient evidence was found for the association between the consumption of processed foods and arterial hypertension. The results reveal the high consumption of ultra-processed foods in developed and middle-income countries, warning of the health risks of such foods, which have a high energy density and are rich in salt, sugar and fat. The findings underscore the urgent need for the adoption of measures that exert a positive impact on the quality of life of populations, especially those at greater risk, such as adults and older people.

1. Introduction

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are industrial formulations and constitute an exposure factor for the development of arterial hypertension (AH) [1,2,3], which is considered the main risk factor for the major cause of mortality throughout the world—cardiovascular disease [4]. The term “ultra-processed” corresponds to one of the four classifications of the NOVA system, which groups foods according to the degree of processing—in natura or minimally processed, cooking ingredients, processed foods (PFs) and UPFs. The UPFs are hypercaloric and have an unbalanced nutritional composition. Such foods have attractive organoleptic characteristics (high palatability and colorful) and are inexpensive, but constitute a risk to human health. Examples include packaged chips, snacks, soft drinks, artificial juices, cookies and frozen/pre-prepared meals [5,6].

The PFs also merit attention. These foods are essentially manufactured with the addition of salt or sugar to an in natura or minimally processed food, such as canned vegetables, fruit in syrup, cheeses and some types of bread [5,6]. The increase in the availability of PFs and UPFs and the simultaneous occurrence of the nutritional transition have altered the eating pattern of populations. Traditional cooking and eating habits based on in natura and minimally processed foods have largely been replaced by convenient PF/UPFs, increasing the risk of the development of diseases [7,8]. Studies report an association between food components such as sodium and alcohol as a risk factor, whereas potassium, magnesium and calcium offer protection from the development of AH [9,10,11,12,13]. To the best of our knowledge, however, few studies have evaluated the impact of the consumption of PFs and UPFs considering AH as the outcome.

From the public health standpoint, it is important to assess the severity and magnitude of AH and its association with the increase in the consumption of PFs and UPFs [8,14]. Changes in eating patterns and lifestyle in populations throughout the world in recent decades underscore the urgent need for interventions on the part of governments to address the increase in the prevalence of AH. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to analyze evidence of the association between the consumption of PFs/UPFs and AH in adults and older people.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 2020 [15]. All information on the search, article selection process and data extraction were previously registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO—CRD42021222514). The following was the guiding question: “Is there an association between processed/ultra-processed foods and arterial hypertension in adults and older people?”

The PICOS acronym was used in the design of the study for the definition of the inclusion and exclusion criteria: P (Population)—adults (20 to 59 years of age) and/or older people (60 years of age or older); I (Intervention/Exposure)—high consumption of processed and ultra-processed foods based on the NOVA classification; C (Comparison)—low consumption of processed and ultra-processed foods based on the NOVA classification; O (Outcome)—arterial hypertension defined based on any diagnostic criteria; S (Type of Study)—observational (cohort, case-control and cross-sectional) and intervention studies (Table S1, Supplementary material).

Studies that satisfied the criteria established using the PICOS method and evaluated the consumption of PFs and/or UPFs and its association with AH in adults and/or older people were included. No restrictions were imposed with regards to language or year of publication. Studies with pregnant women, children and adolescents, those that addressed a disease other than AH, review articles, guidelines, letters and editorials were excluded. Studies that used the terms “processed” or “ultra-processed” but did not follow the requirements of the NOVA classification proposed by Monteiro et al. (2010) [5] were not included.

2.1. Search Strategy/Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Two reviewers (S.S.B. and L.C.M.S.) performed independent searches of the PubMed, Embase and LILACS databases on 20 May 2021. For the EMBASE database, the search was refined by selecting only articles and articles in press among the different publication types. The following search strategies were employed:

- -

- PubMed: (“ultra-processed food” OR “ultra-processed foods” OR “ultraprocessed food” OR “ultraprocessed foods” OR “ultra-processed product” OR “ultra-processed products” OR “ultra-processing” OR “food processing” OR “processed food” OR “processed foods” OR “NOVA” OR “NOVA system” OR “NOVA food classification” OR “NOVA classification system”) AND (hypertension OR “high blood pressure” OR “high blood pressures” OR “blood pressure” OR “systolic pressure” OR “diastolic pressure” OR “systolic blood pressure” OR “diastolic blood pressure”) AND (adult OR adults OR aged OR “middle aged” OR elderly OR “older adult”).

- -

- Embase: (“ultra-processed food” OR “ultra-processed foods” OR “ultraprocessed food” OR “ultraprocessed foods” OR “ultra-processed product” OR “ultra-processed products” OR “ultra-processing” OR “food processing” OR “processed food” OR “processed foods” OR “NOVA” OR “NOVA system” OR “NOVA food classification” OR “NOVA classification system”) AND (hypertension OR “high blood pressure” OR “high blood pressures” OR “blood pressure” OR “systolic pressure” OR “diastolic pressure” OR “systolic blood pressure” OR “diastolic blood pressure”) AND (adult OR adults OR aged OR “middle aged” OR elderly OR “older adult”).

- -

- LILACS: (“alimento ultra-processado” OR “alimentos ultra-processados” OR “alimento ultraprocessado” OR “alimentos ultraprocessados” OR “produto ultra-processado” OR “produtos ultra-processados” OR “ultra-processamento” OR “processamento de alimento” OR “alimento processado” OR “alimentos processados” OR “NOVA” OR “sistema NOVA” OR “classificação de alimentos NOVA” OR “sistema de classificação de alimentos NOVA”) AND (hipertensão OR “hipertensão arterial sistêmica” OR “pressão arterial elevada” OR “pressão arterial” OR “pressão sistólica” OR “pressão diastólica” OR “pressão arterial sistólica” OR “pressão arterial diastólica”) AND (adulto OR adultos OR idoso OR idosos).

2.2. Article Selection Process and Data Extraction

Articles were retrieved from the databases using the search terms. Duplicates were removed and the selection process for the review was conducted in two steps. The titles and abstracts were analyzed for the preselection of potentially eligible articles and the exclusion of those that did not meet the objectives of the review. The preselected articles were then submitted to full-text analysis for the selection of those that met the inclusion criteria. The articles selected by each reviewer were compared. In cases of a divergence of opinion, a third reviewer (D.F.d.O.S.) was consulted to make the decision regarding inclusion or exclusion.

The following data were extracted from the articles selected for the present review: author and year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, language in which the article was published, sample size, age of participants, food consumption assessment method, denomination and composition of dietary components, method used in the statistical analysis, criteria for the diagnosis of AH, energy contribution of PFs/UPFs and results of associations between processing of foods and AH.

2.3. Appraisal of Methodological Quality

The appraisal of methodological quality and risk of bias in the cohort and cross-sectional studies was performed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [16] and adapted Newcastle–Ottawa scale [17], respectively. The articles were classified as “poor”, “fair”, “good” or “excellent” when achieving scores of 0–3, >3–6, >6–8 or >8–9, respectively.

Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) [18] was used for the narrative description of the data on the association between the consumption of PFs/UPFs and AH in adults and older people. The number of studies with a positive association between PFs/UPFs and AH was compared to the number reporting an inverse association and those reporting no association to determine the summary of the evidence.

3. Results

3.1. Article Selection Process

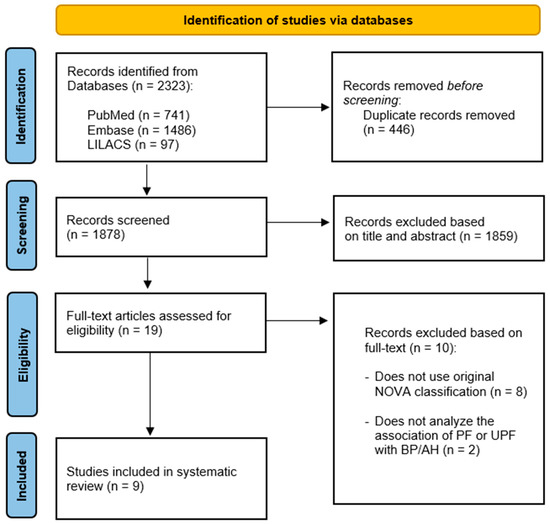

The search of the databases led to the retrieval of 2323 articles: 741 in PubMed, 1486 in Embase and 97 in LILACS. After the removal of duplicates, the articles were screened based on the reading of the title and abstract. Review articles, non-observational studies, those that evaluated outcomes other than AH, those with samples of children, adolescents or pregnant women and animal studies were excluded. Ten potentially eligible articles were submitted to full-text analysis, nine of which were included in the present review. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the article selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the included studies.

3.2. Overview and Characteristics of Studies

The nine articles selected were published in the last five years (2017 to 2021) and were conducted in seven countries of the Americas and two in Europe: Brazil (n = 3) [2,19,20], USA (n = 2) [21,22], Canada (n = 1) [3], Mexico (n = 1) [23] and Spain (n = 2) [1,24]. The objective of the studies and dietary component analyzed are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of studies selected for present review (n = 9).

Six studies had samples composed only of adults [1,2,3,19,21,23] and three had sample composed of adults and older people [20,22,24]. One study only evaluated women [23]. A total of 114,849 individuals participated in the nine studies. Five of the studies had a cross-sectional design [3,19,21,22,24] and four were cohort studies [1,2,20,23] (Table 2). The average duration of the cohort studies was 3.5 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies selected for present review (n = 9).

3.3. Processed and Ultra-Processed Food Consumption

The predominant data collection tool for the food consumption assessment in the different populations was the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (n = 5), followed by the 24-h recall (n = 3) and food record (n = 1). All studies used the NOVA classification proposed by Monteiro et al., (2010) [5] to categorize the foods based on the degree of processing. For the present review, only analysis performed with foods from the processed and ultra-processed categories were considered. Seven studies exclusively analyzed UPFs and two analyzed both PFs and UPFs. No studies analyzed PFs alone. The average daily caloric contribution ranged from 6.2 to 9.9% for PFs and from 7.7% [19] to 55.5% [22] for UPFs. American and Canadian populations had the highest consumption of UPFs.

3.4. Association between Processing of Food and Arterial Hypertension

Seven studies included in the present review strictly analyzed the association between the consumption of PFs and/or UPFs and BP and/or AH [1,2,19,20,21,23,24]. Two studies analyzed the association between the consumption of these foods and metabolic syndrome [22], obesity, diabetes, AH and heart disease [3]. Both studies were included because BP/AH was one of the variables evaluated in relation to UPFs. The effect measures used to determine the association between the consumption of PFs/UPFs and AH were the odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio (HR), incidence rate ratio (IRR) and risk ratio (RR) with respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). The types of statistical analysis used in each study are described in Table 2.

Among the articles analyzed, eight used diverse covariables in the multivariate analyses. However, only five studiesowever, only Ho [1,2,20,22,24] included biochemical data as adjustment variables in the regression models. Among these studies, one [22] analyzed the association between UPFs and metabolic syndrome and not specifically the association between UPFs and AH/BP. Steele et al. [22] found a significant association between the quintiles of UPF consumption and high BP.

Nearly all studies (n = 7) found a positive association between the consumption of PFs/UPFs and AH/BP. Only two cross-sectional studies [19,24] found no statistically significant difference in the average SBP and DBP based on the consumption of these foods.

3.5. Quality Appraisal

The complete appraisal of the methodological quality of the articles is described in Supplementary Material Table S2. The cross-sectional studies had scores ranging from 4 to 7 and the cohort studies had scores ranging from 6 to 7.

4. Discussion

The present systematic review found a positive association between the consumption of UPFs and BP/AH, pointing out the health risk of the consumption of highly PFs, which have a high energy density and are rich in salt, sugar and fat. Previous reviews have also evaluated the effect of these foods on different health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, overweight, obesity, depression and metabolic syndrome [31,32,33,34,35]. Such findings offer evidence that the consumption of these foods has negative consequences for human health.

The sample sizes in the articles of the present review ensure representativity and confer reliability to the results, suggesting adequate quality of the evidence presented. Only two cross-sectional studies [19,24] found no statistically significant difference in the average SBP and DBP based on the consumption of UPFs. In one of the articles, although the methodological quality of the study was considered satisfactory, the sample size was relatively small (64 participants) [19]. On the other [24], the consumption of UPFs was significantly associated only with anthropometric data (weight, BMI and waist circumference) and biochemical data (HDL and creatinine). However, there is a consensus that overweight, obesity, excess abdominal fat and low HDL are cardiometabolic risk factors and caution should be exercised when consuming UPFs [36,37].

Most of the participants in the studies included in the present review had a higher education (more than 90,000 individuals). In the Brazilian study conducted by Scaranni et al. [20], in which 58% of the sample had a university degree, a higher level of schooling was associated with a greater consumption of UPFs. Three explanations may be offered for these findings: (1) individuals with higher education may have less time available to prepare meals due to their academic and professional activities; (2) the possibility of a higher income in this population implies greater freedom in food choices, with the acquisition of inadequate foods; (3) UPFs are products that may meet the needs of this population in terms of practicality, variety and convenience, constituting an exposure factor for AH. The influence of schooling and income level on diet indicates the need to evaluate different groups in population-based studies for a more precise identification of eating patterns.

Most of the articles included in this review were of population-based studies with representative samples and the investigation of different variables. Thus, the authors sought to investigate other possible factors (sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, health conditions, etc.) correlated with the consumption of UPFs and AH. For these types of analyses, multiple regression models were used to control for the effect of confounding variables in the associations. One study used the Student’s t-test as the analysis method [19]. The statistical analyses employed in the studies were adequate to the design and objective, making the results more consistent.

The use of adequate data collection tools for the determination of food intake ensures greater reliability of the results. Moreover, it is important for the instruments used to be validated specifically for the objectives and population one wishes to evaluate, such as the assessment tool developed by Mota et al. [38], which enhances the quality of the evidence [39]. In the present review, five studies used a validated FFQ [1,2,20,23,24] for the populations studied, but without validation for the assessment of food intake according to the degree of processing. This factor increases the likelihood of the underestimation or overestimation of the consumption of PFs/UPFs. In a previous systematic review, Marino et al. [33] found that most data on food intake were from FFQs not validated for estimating UPFs and, therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, especially when used to analyze associations with health status.

Two cross-sectional studies found associations between the high consumption of UPFs in American [21] and Canadian [3] populations and the development of AH. The UPFs have dominated the food supply in high-income countries and the consumption of these foods is rapidly increasing in middle-income countries [40]. Studies with national representativeness conducted in Canada and the USA have identified changes in eating patterns [28,30]. In Canada, whole or minimally PFs and cooking ingredients have been replaced with ready-to-eat meals and other UPFs [28]. A study conducted in the USA found that the consumption of UPFs accounted for 57.9% of the calorie intake of Americans [30].

The cohort studies included in the present review conducted in Brazil also found a greater risk of the development of AH among individuals who consumed more UPFs, and the study conducted in Mexico found an association between subgroups of UPFs (meats and beverages) and an increase in the incidence of AH [2,20,23]. These associations reflect an increase in urban living and the influence of foreign markets on the Latin American economy [41]. A study on the risk of the development of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged Americans demonstrated that the prevalence of AH was higher among those who consumed larger quantities of UPFs [42]. These data underscore the need to investigate the eating habits of populations and associated factors and establish strategies to attenuate the negative consequences of the excessive consumption of these foods with regards to BP.

For the assessment of AH or altered BP, most of the cross-sectional studies measured BP at the time of data collection [19,21,22,24]. Only one study obtained this information based on a self-declared medical diagnosis during the interview [3]. The cohort studies collected these data through questionnaires sent to the participants during the follow-up period. Some considered AH only in the occurrence of a self-declaration of a medical diagnosis of AH [1], and others considered AH in the occurrence a self-declared high BP or the use of an antihypertensive in a particular period of time [2,23]. To minimize errors during the gathering of information, the cohort studies previously validated the tool used for the collection of BP data. Only one cohort study involved the measurement of BP throughout the follow-up period and also obtained information on the use of antihypertensives [20].

Few studies evaluated the consumption of PFs [2,19] and it was, therefore, not possible to measure the impact of the consumption of these foods on BP or the development of AH. The majority of studies investigated the association between the consumption of UPFs and AH. Ultra-processing poses a public health challenge, as such foods have the advantages of being inexpensive, highly palatable and convenient and have a long shelf-life, but are characteristically energy dense and have high contents of fat, sugar and salt. Moreover, the formulation, packaging and marketing often induce excessive consumption [25]. Ultra-processing leads to the production of unhealthy foods that are rich in energy and poor in protective micronutrients and fiber, resulting in “empty calories” [43]. Thus, there is a need for large-scale strategies and public policies that involve all actors participating in this process—from the production chain (through the promotion of agroecology and sustainable food systems) to the consumer—in order to reduce the consumption of UPFs and encourage healthier eating habits.

The Food and Agriculture Organization established goals to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns (12th Sustainable Development Goal: Responsible Consumption and Production). For future food systems to be sustainable, new (or forgotten) ideas, practices and forms of organization are needed to ensure that all activities that bring foods grown in soil or aquatic organisms to the table of populations are environmentally sustainable as well as economically inclusive and socially fair. It is, therefore, fundamental to seek joint strategies for the protection of the health of populations and intervene on local, regional, national and international levels with the participation of civil society, researchers, governments and the private sector [44].

The innovative NOVA food classification method based on the degree of processing [5] has altered the interpretation of what constitutes healthy foods and the repercussions with regards to health and the development of diseases. The notion that foods should be analyzed in their totality, encompassing the content of nutrients and ingredients, highlights the importance of considering all aspects from the beginning of the food production process to the consumer’s table. This perspective poses challenges for the creation of new assessment tools and investigation methods that identify the impact of the degree of food processing on the health of the population.

Despite studies in the literature involving the NOVA classification, analyses on the association between PFs/UPFs and AH are scarce, especially those involving adults and older people. In the present review, only nine such studies were found, most of which were conducted in the Americas. To the best of our knowledge, no studies of this type have been conducted with Asian or African communities. Thus, there is a gap in knowledge to be filled with further studies. Among the scientific publications, we found a diversity of studies involving samples of children [45], adolescents [46] and pregnant women [47], as well as those that investigated the association between UPFs and the occurrence of obesity/weight gain [48], metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Studies with an adequate, robust methodological design for the determination of the cause-and-effect relationship, such as randomized clinical trials, involving representative populations on different continents, could further clarify the impact of PFs/UPFs on BP and the development of AH, especially in populations at greater risk, such as adults and older people.

Limitations and Strengths

The present review has limitations that should be considered. First, studies with different methodological designs (cross-sectional and cohort) were included. This decision was made due to the scarcity of studies investigating the association between PFs/UPFs and BP/AH in adults and older people. Second, some of the studies used a food frequency questionnaire not specifically validated for the collection of data on food intake according to the NOVA classification, which may have resulted in the underestimation or overestimation of the consumption of PFs/UPFs. Third, few studies were found that evaluated the consumption of PFs and involved the older population, possibly due to the fact that PFs are not considered to be as harmful as UPFs and that more discerning methodological criteria are needed for the assessment of older people.

This review also has strong points, such as the originality of the study in terms of the investigation of the association between the consumption of PFs/UPFs and BP/AH. To the best of our knowledge, this review is a pioneering study on this subject. Secondly, the review presents data on the main risk factor for cardiovascular disease and, consequently, the main cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world—hypertension. Lastly, a rigorous selection of articles was performed according to predetermined inclusion criteria, with the inclusion only of studies in which the classification of PFs/UPFs faithfully followed the characteristics proposed by the NOVA system.

5. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the present review, UPFs are associated with a greater risk of developing AH in the adult population and older people. The evidence underscores the need to investigate the eating habits of populations due to the increase in the consumption of unhealthy foods, which can have negative health consequences. Such knowledge could assist in the adoption of measures that have a positive impact on the transformation of the health scenario in the long term.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu14061215/s1, Table S1: PICOS acronym used in the design of the study (n = 9), Table S2: Methodological quality of studies selected for present review (n = 9).

Author Contributions

Designed the research, S.S.B., D.F.d.O.S., J.B.P., C.d.O.L., M.M.G.D.L., S.C.V.C.L.; conducted the systematic literature search, S.S.B., L.C.M.S.; performed the quality assessment and the data extraction, S.S.B., L.C.M.S.; wrote the paper; S.S.B., L.C.M.S.; critically reviewed the manuscript, D.F.d.O.S., J.B.P., K.C.M.d.S.E., C.d.O.L., M.M.G.D.L., S.C.V.C.L.; and approved the final manuscript, S.C.V.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

References

- De Deus Mendonça, R.; Lopes, A.C.S.; Pimenta, A.M.; Gea, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and the Incidence of Hypertension in a Mediterranean Cohort: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am. J. Hypertens. 2017, 30, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rezende-Alves, K.; Hermsdorff, H.H.M.; Miranda, A.E.D.S.; Lopes, A.C.S.; Bressan, J.; Pimenta, A.M. Food processing and risk of hypertension: Cohort of Universities of Minas Gerais, Brazil (CUME Project). Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 4071–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardocci, M.; Polsky, J.Y.; Moubarac, J.-C. Consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with obesity, diabetes and hypertension in Canadian adults. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 112, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Word Health Organization. Technical Package for Cardiovascular Disease Management in primary Health Care: Healthy-Lifestyle Counselling; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; de Castro, I.R.R.; Cannon, G. Uma nova classificação de alimentos baseada na extensão e propósito do seu processamento. Cad. Saúde Pública 2010, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Ricardo, C.Z.; Steele, E.M.; Levy, R.B.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. The Share of Ultra-Processed Foods Determines the Overall Nutritional Quality of Diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, P.; Machado, P.; Santos, T.; Sievert, K.; Backholer, K.; Hadjikakou, M.; Russell, C.; Huse, O.; Bell, C.; Scrinis, G.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Lawrence, M.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Machado, P.P. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; 48p. [Google Scholar]

- Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; McQueen, M.; Dagenais, G.; Wielgosz, A.; Lear, S.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Yi, S.; et al. Association of dietary nutrients with blood lipids and blood pressure in 18 countries: A cross-sectional analysis from the PURE study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, L.; Trieu, K.; Yoshimura, S.; Neal, B.; Woodward, M.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Li, Q.; Lackland, D.T.; Leung, A.A.; Anderson, C.A.M.; et al. Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2020, 368, m315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santana, N.M.T.; Mill, J.G.; Velasquez-Melendez, G.; Moreira, A.; Barreto, S.; Viana, M.C.; Molina, M.D.C.B. Consumption of alcohol and blood pressure: Results of the ELSA-Brasil study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Fang, X.; Wei, X.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Chen, Q.; Fan, Z.; Aaseth, J.; Hiyoshi, A.; He, J.; et al. Dose-response relationship between dietary magnesium intake, serum magnesium concentration and risk of hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadifard, N.; Gotay, C.; Humphries, K.H.; Ignaszewski, A.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Sarrafzadegan, N. Electrolyte minerals intake and cardiovascular health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaime, P.; Campello, T.; Monteiro, C.; Bortoletto, A.P.; Yamaoka, M.; Bomfim, M. Diálogo sobre Ultraprocessados: Soluções para Sistemas Alimentares Saudáveis e Sustentáveis; Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021; 45p. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2014. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- The Modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale for Cross Sectional Studies. Available online: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=info%3Adoi/10.1371/journal.pone.0136065.s004&type=supplementary (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Conceição, A.R.; Fonseca, P.C.D.A.; Morais, D.D.C.; De Souza, E.C.G. Association of the degree of food processing with the consumption of nutrients and blood pressure. O Mundo da Saúde 2019, 43, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaranni, P.d.O.d.S.; Cardoso, L.d.O.; Chor, D.; Melo, E.C.P.; Matos, S.M.A.; Giatti, L.; Barreto, S.M.; Fonseca, M.d.J.M.d. Ultra-processed foods, changes in blood pressure and incidence of hypertension: The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3352–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiljanec, K.; Mbakwe, A.U.; Ramos-Gonzalez, M.; Mesbah, C.; Lennon, S.L. Associations of Ultra-Processed and Unprocessed/Minimally Processed Food Consumption with Peripheral and Central Hemodynamics and Arterial Stiffness in Young Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Juul, F.; Neri, D.; Rauber, F.; Monteiro, C.A. Dietary Share of Ultra-Processed Foods and Metabolic Syndrome in the US Adult Population. Prev. Med. 2019, 125, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge, A.; Canella, D.S.; López-Olmedo, N.; Lajous, M.; Cortés-Valencia, A.; Stern, D. Ultraprocessed beverages and processed meats increase the incidence of hypertension in Mexican women. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 126, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; San-Cristobal, R.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Martínez-González, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Castañer, O.; Martinez, J.; Alonso-Gómez, A.M.; Wärnberg, J.; et al. Use of Different Food Classification Systems to Assess the Association between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Cardiometabolic Health in an Elderly Population with Metabolic Syndrome (PREDIMED-Plus Cohort). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA Food Classification and the Trouble with Ultra-Processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; de Castro, I.R.; Cannon, G. Increasing Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Likely Impact on Human Health: Evidence from Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.; Moubarac, J.C.; Jaime, P.; Martins, A.P.; Canella, D.; Louzada, M.; Parra, D. NOVA. The star shines bright. World Nutr. 2016, 7, 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Moubarac, J.-C.; Batal, M.; Martins, A.P.B.; Claro, R.; Levy, R.B.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C. Processed and Ultra-processed Food Products: Consumption Trends in Canada from 1938 to 2011. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2014, 75, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubarac, J.-C.; Batal, M.; Louzada, M.L.; Martinez Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Predicts Diet Quality in Canada. Appetite 2017, 108, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Baraldi, L.G.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-Processed Foods and Added Sugars in the US Diet: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pagliai, G.; Dinu, M.; Madarena, M.P.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Sofi, F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araújo, T.; de Moraes, M.; Magalhães, V.; Afonso, C.; Santos, C.; Rodrigues, S. Ultra-Processed Food Availability and Noncommunicable Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Puppo, F.; Del Bo’, C.; Vinelli, V.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Martini, D. A Systematic Review of Worldwide Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods: Findings and Criticisms. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth, L.; Machado, P.; Zinöcker, M.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, J.; Nie, J. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, T.; Borghi, C.; Charchar, F.; Khan, N.A.; Poulter, N.R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Ramirez, A.; Schlaich, M.; Stergiou, G.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 982–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, W.K.S.; Rodrigues, C.I.S.; Bortolotto, L.A.; Mota-Gomes, M.A.; Brandão, A.A.; Feitosa, A.D.D.M.; Machado, C.A.; Poli-De-Figueiredo, C.E.; Amodeo, C.; Mion, D.; et al. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial—2020. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2021, 116, 516–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, V.W.d.L.; Lima, S.C.V.C.; Marchioni, D.M.L.; Lyra, C.D.O. Food frequency questionnaire for adults in Northeast Region of Brazil: Emphasis on extent and purpose of food processing. Rev. Saúde Pública 2021, 55, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Assessment: A Resource Guide to Method Selection and Application in Low Resource Settings; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; 152p. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-Processed Products Are Becoming Dominant in the Global Food System. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 2), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.A.; Adams, M.; Sabaté, J. Review: The Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Non-communicable Diseases in Latin America. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Vaidean, G.; Lin, Y.; Deierlein, A.L.; Parekh, N. Ultra-Processed Foods and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A. Characterization of the Degree of Food Processing in Relation With Its Health Potential and Effects. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 85, 79–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment. Enabling Sustainable Food Systems: Innovators’ Handbook; FAO and INRAE: Rome, Italy, 2020; 233p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martines, R.M.; Machado, P.; Neri, D.A.; Levy, R.B.; Rauber, F. Association between watching TV whilst eating and children’s consumption of ultraprocessed foods in United Kingdom. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, P.R.E.S.; Noll, M.; de Abreu, L.C.; Baracat, E.C.; Silveira, E.A.; Sorpreso, I.C.E. Ultra-processed food consumption by Brazilian adolescents in cafeterias and school meals. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomes, C.D.B.; Malta, M.B.; Louzada, M.L.D.C.; Benício, M.H.D.; Barros, A.J.D.; Carvalhaes, M.A.D.B.L. Ultra-processed Food Consumption by Pregnant Women: The Effect of an Educational Intervention with Health Professionals. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Ayuketah, A.; Brychta, R.; Cai, H.; Cassimatis, T.; Chen, K.; Chung, S.T.; Costa, E.; Courville, A.; Darcey, V.; et al. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 67–77.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).