Access to Healthy Wheat and Maize Processed Foods in Mexico City: Comparisons across Socioeconomic Areas and Store Types

Abstract

1. Introduction

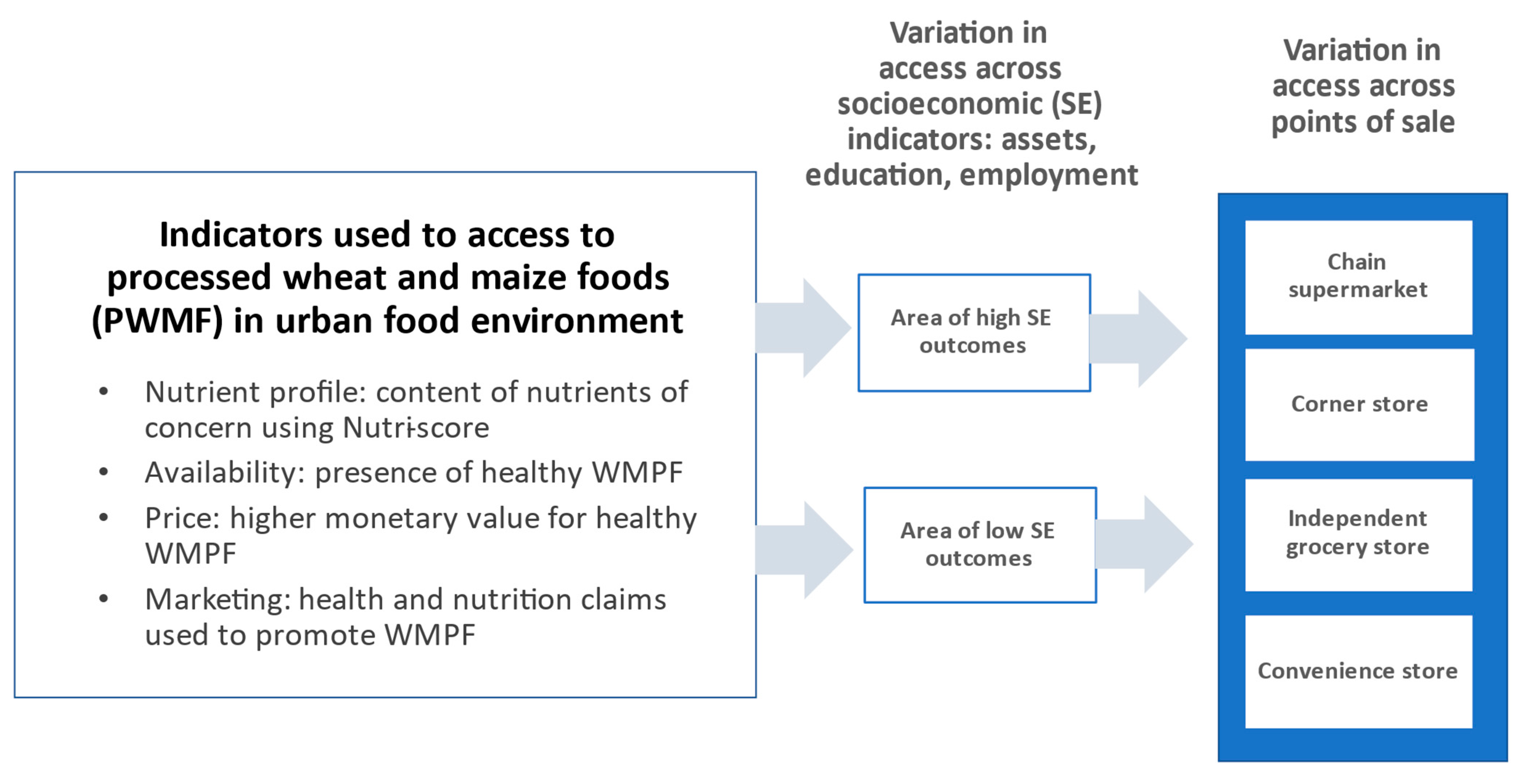

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection and Management

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Food Supply and Stock of Healthy WMPFs across Socioeconomic (SE) Areas and Food Retail Outlets

3.2. Availability of WMPFs across Socioeconomic (SE) Areas by Nutri-Score Profile

3.3. Price Variation of WMPFs across Socioeconomic (SE) Areas and Retail Outlets

3.4. Health and Nutrition Claims Displayed in WMPFs across Socioeconomic (SE) Areas

4. Discussion

4.1. Most WMPFs Are Not Healthy

4.2. Consumers in Richer Areas Have Access to a Greater Diversity of WMPFs

4.3. Specialization in Retail Stores across Socioeconomic Areas

4.4. Higher Prices Prevail for Unhealthy WMPFs

4.5. Health and Nutrition Claims Frequent in Healthy and Unhealthy WMPFs

4.6. From Traditional Healthy Foods to Unhealthy WMPFs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sgaier, S.K.; Engl, E.; Kretschmer, S. Time to Scale Psycho-Behavioral Segmentation in Global Development. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2018, 16, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, A.; Loar, R.; England Kramer, A. The impact of market segmentation and social marketing on uptake of preventive programmes: The example of voluntary medical male circumcision. A literature review. Gates Open Res. 2018, 2, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zanden, L.D.; van Kleef, E.; de Wijk, R.A.; van Trijp, H.C. Understanding heterogeneity among elderly consumers: An evaluation of segmentation approaches in the functional food market. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2014, 27, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sax, J.K.; Doran, N. Food Labeling and Consumer Associations with Health, Safety, and Environment. J. Law Med. Ethics 2016, 44, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermel, A.; Mendoza, J.; Henson, S.; Dukeshire, S.; Pasut, L.; Emrich, T.E.; Lou, W.; Qi, Y.; L’Abbé, M.R. Canadians’ Perceptions of Food, Diet, and Health—A National Survey. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.S.; Rickard, B.J.; Rossman, W.J. Product Differentiation and Market Segmentation in Applesauce: Using a Choice Experiment to Assess the Value of Organic, Local, and Nutrition Attributes. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2009, 38, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparke, K.; Menrad, K. Cross-European and Functional Food-Related Consumer Segmentation for New Product Development. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2009, 15, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdurme, A.; Viaene, J. Consumer beliefs and attitude towards genetically modified food: Basis for segmentation and implications for communication. Agribusiness 2003, 19, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Gracia, A.; Garcia, M. Market Segmentation and Willingness to Pay for Organic Products in Spain. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2000, 3, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, R.C. Strengthening the core, improving access: Bringing healthy food downtown via a farmers’ market move. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 67, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, J. Beyond the Supermarket Solution: Linking Food Deserts, Neighborhood Context, and Everyday Mobility. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2015, 106, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraak, V.; Swinburn, B.; Lawrence, M.; Harrison, P. An accountability framework to promote healthy food environments. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2467–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moberg, E.; Allison, E.H.; Harl, H.K.; Arbow, T.; Almaraz, M.; Dixon, J.; Scarborough, C.; Skinner, T.; Rasmussen, L.V.; Salter, A.; et al. Combined innovations in public policy, the private sector and culture can drive sustainability transitions in food systems. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.E.; Keane, C.R.; Burke, J.G. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health Place 2010, 16, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Aggarwal, A.; Walls, H.; Herforth, A.; Drewnowski, A.; Coates, J.; Kalamatianou, S.; Kadiyala, S. Concepts and critical perspectives for food environment research: A global framework with implications for action in low- and middle-income countries. Global Food Secur. 2018, 18, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Nettleton, J.A. Availability of healthy foods and dietary patterns: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Timperio, A.; Crawford, D. Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in food access and affordability. Health Place 2009, 15, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartin, M. Food deserts and nutritional risk in Paraguay. Am. J. Human Biol. 2012, 24, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.C.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Maria do Rosario, D.O.; Jaime, P.C. Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics and differences in the availability of healthy food stores and restaurants in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Health Place 2013, 23, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Healthy nutrition environments: Concepts and measures. Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 19, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Long, M.W.; Brownell, K.D. The Impact of Food Prices on Consumption: A Systematic Review of Research on the Price Elasticity of Demand for Food. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, O.; Rodriguez, N.; Mercurio, A.; Bragg, M.; Elbel, B. Supermarket retailers’ perspectives on healthy food retail strategies: In-depth interviews. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggins, S.; Keats, S. The Rising Cost of a Healthy Diet. Overseas Development Institute. 2015. Available online: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/9580.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Katz, D.L.; Doughty, K.; Njike, V. A cost comparison of more and less nutritious food choices in US supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, P.B. Nutrition Policies Designed to Change the Food Environment to Improve Diet and Health of the Population. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser. 2019, 92, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jürkenbeck, K.; Zühlsdorf, A.; Spiller, A. Nutrition Policy and Individual Struggle to Eat Healthily: The Question of Public Support. Nutrients 2020, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.; Hawkes, C.; Webb, P. A new global research agenda for food. Nature 2016, 540, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, C. El Colegio de México, Desigualdades en México 2018. Foro Int. 2019, 2, 521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ferrer, C.; Auchincloss, A.H.; de Menezes, M.C.; Kroker-Lobos, M.F.; Cardoso, L.d.O.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T. The food environment in Latin America: A systematic review with a focus on environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 3447–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Vielma-Orozco, E.; Heredia-Hernández, O.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Mojica-Cuevas, J.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Santaella-Castell, J.A.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018–19: Resultados Nacionales; Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública: Cuernavaca, México, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balderas Martínez, L.A. Alimentos procesados. In Promexico Inversion y Comercio; Unidad de Inteligencia de Negocios, Secretaria de Economia: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- García-Chávez, C.G.; Monterrubio-Flores, E.; Ramírez-Silva, C.I.; Aburto, T.C.; Pedraza, L.S.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Contribución de los alimentos a la ingesta total de energía en la dieta de los mexicanos mayores de cinco años. Salud Pública México 2020, 62, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrón-Ponce, J.A.; Flores, M.; Cediel, G.; Monteiro, C.A.; Batis, C. Associations between Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Intake of Nutrients Related to Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases in Mexico. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1852–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.; Reyes, M.; Corvalán, C. Photographic Methods for Measuring Packaged Food and Beverage Products in Supermarkets. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e001016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantal, J.; Hercberg, S.; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Development of a new front-of-pack nutrition label in France: The five-colour Nutri-Score. Public Health Panor. 2017, 3, 712–725. [Google Scholar]

- Sistema de Información Económica. Mercado Cambiario. Available online: https://www.banxico.org.mx/tipcamb/main.do?page=tip&idioma=sp (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Dean, N.; Pagano, M. Evaluating Confidence Interval Methods for Binomial Proportions in Clustered Surveys. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2015, 3, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, W. Regression Standard Errors in Clustered Samples. In Stata Technical Bulletin 1993, 13, 19–23. Available online: https://www.stata.com/products/stb/journals/stb13.html (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Pan American Health Organization; World Health Organization. Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B.; Villamor, E.; Mora-Plazas, M.; Marin, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Baylin, A. Processed and ultra-processed foods are associated with lower-quality nutrient profiles in children from Colombia. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Zancheta Ricardo, C.Z.; Martinez Steele, E.; Bertazzi Levy, R.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Zhao, L.; Wu, T. Association between access to convenience stores and childhood obesity: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e21908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Food Systems for Health: Information Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- López-Olmedo, N.; Popkin, B.M.; Taillie, L.S. The socioeconomic disparities in intakes and purchases of less-healthy foods and beverages have changed over time in urban Mexico. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.; Barnhill, A.; Sharfstein, J.M. The evidence and acceptability of taxes on unhealthy foods. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2018, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpyn, A.; DeWeese, R.S.; Pelletier, J.E. Examining the Feasibility of Healthy Minimum Stocking Standards for Small Food Stores. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.N. Lack of Healthy Food in Small-Size to Mid-Size Retailers Participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minnesota, 2014. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2015, 12, E135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, E.C.; Pelletier, J.E.; Harnack, L.; Erickson, D.J.; Laska, M.N. Differences in healthy food supply and stocking practices between small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 19, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, R.; Lopes, C.; Perelman, J. Healthy eating: A privilege for the better-off? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhen, C. Healthy food, unhealthy food and obesity. Econ. Lett. 2008, 100, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.D.; Alderman, H.H. The relative caloric prices of healthy and unhealthy foods differ systematically across income levels and continents. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 2020–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Colchero, M.A.; Sánchez-Romero, L.M. Posicionamiento sobre los impuestos a alimentos no básicos densamente energéticos y bebidas azucaradas. Salud Pública México 2018, 60, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falbe, J.; Thompson, H.R.; Becker, C.M.; Rojas, N.; McCulloch, C.E.; Madsen, K.A. Impact of the Berkeley Excise Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, T.L.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Pega, F.; Gartiehner, G.; Fenton, C.; Griebler, U. Taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages for reducing their consumption and preventing obesity or other adverse health outcomes. Cochrane Database Sys. Rev. 2016, CD012319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rayner, M.; Wood, A.; Lawrence, M.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Albert, J.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; Kumanyika, S.; et al. INFORMAS Monitoring the health-related labelling of foods and non-alcoholic beverages in retail settings. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buul, V.J.; Brouns, F.J.P.H. Nutrition and health claims as marketing tools. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M. A systematic review, and meta-analyses, of the impact of health-related claims on dietary choices. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieke, S.; Kuljanic, N.; Pravst, I. Prevalence of Nutrition and Health-Related Claims on Pre-Packaged Foods: A Five-Country Study in Europe. Nutrients. 2016, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrill, L.; Wood, D.; Cates, S.; Lando, A.; Zhang, Y. Vitamin-Fortified Snack Food May Lead Consumers to Make Poor Dietary Decisions. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mano, F.; Ikeda, K.; Joo, E. The Effect of White Rice and White Bread as Staple Foods on Gut Microbiota and Host Metabolism. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaim, M. Globalisation of agrifood systems and sustainable nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranum, P.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Global maize production, utilization, and consumption. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Food Systems Summit 2021. Discusion Starter. Action Track 1. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/unfss-at1-discussion_starter-dec2020.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2021).

| Nutri-Score Profile by Retail Outlet | Unique WMPFs (n) | Distribution across SE Areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Low and High SE Areas | % Only Low SE Area | % Only High SE Area | ||

| Supermarkets | ||||

| Unhealthy WMPFs | 1212 | 23.3 | 9.6 | 67.1 |

| Healthy WMPFs | 614 | 12.1 | 8.6 | 79.3 |

| Total WMPFs | 1826 | 19.5 | 9.3 | 71.2 |

| Independently owned grocery stores | ||||

| Unhealthy WMPFs | 340 | 72.9 | 6.8 | 20.3 |

| Healthy WMPFs | 45 | 68.9 | 6.7 | 24.4 |

| Total WMPFs | 385 | 72.5 | 6.7 | 20.8 |

| Convenience stores | ||||

| Unhealthy WMPFs | 375 | 62.4 | 7.5 | 30.1 |

| Healthy WMPFs | 29 | 51.7 | 3.5 | 44.8 |

| Total WMPFs | 404 | 61.6 | 7.2 | 31.2 |

| Neighborhood corner stores | ||||

| Unhealthy WMPFs | 474 | 67.9 | 19.8 | 12.2 |

| Healthy WMPFs | 120 | 47.5 | 37.5 | 15.0 |

| Total WMPFs | 594 | 63.8 | 23.4 | 12.8 |

| Total | ||||

| Unhealthy WMPFs | 1754 | 30.2 | 13.3 | 56.5 |

| Healthy WMPFs | 708 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 73.9 |

| Total WMPFs | 2462 | 25.5 | 13.0 | 38.5 |

| Food Product Category | WMPFs (n) | Distribution of WMPFs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Low and High SE Areas | % Only Low SE Area | % Only High SE Area | ||

| Nutri-Score Profile A 2 | ||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 62 | 8.1 | 16.1 | 75.8 |

| Breakfast cereals | 11 | 18.2 | 9.1 | 72.7 |

| Salty snacks | 16 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 93.8 |

| Cookies | 19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Flour | 64 | 28.1 | 18.8 | 53.1 |

| Breads | 146 | 68.5 | 0.0 | 31.5 |

| Bars and pastries | 12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Pastas | 492 | 42.5 | 15.0 | 42.5 |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 67 | 37.3 | 1.5 | 61.2 |

| Total WMPFs classified | 889 | 40.4 | 11.1 | 48.5 |

| Nutri-Score profile B 3 | ||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 76 | 57.9 | 5.3 | 36.8 |

| Breakfast cereals | 37 | 37.8 | 18.9 | 43.2 |

| Salty snacks | 26 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 96.2 |

| Cookies | 37 | 48.7 | 5.4 | 46.0 |

| Flour | 21 | 42.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Breads | 155 | 61.9 | 0.0 | 38.1 |

| Bars and pastries | 6 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 83.3 |

| Pastas | 23 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 46 | 54.4 | 13.0 | 32.6 |

| Total WMPFs classified | 427 | 48.2 | 6.3 | 45.4 |

| Nutri-Score profile C 4 | ||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 138 | 56.5 | 5.8 | 37.7 |

| Breakfast cereals | 157 | 43.3 | 5.1 | 51.6 |

| Salty snacks | 107 | 48.6 | 13.1 | 38.3 |

| Cookies | 155 | 47.7 | 1.9 | 50.3 |

| Flour | 96 | 72.9 | 14.6 | 12.5 |

| Breads | 120 | 61.7 | 1.7 | 36.7 |

| Bars and pastries | 45 | 51.1 | 2.2 | 46.7 |

| Pastas | 9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 98 | 55.1 | 9.2 | 35.7 |

| Total WMPFs classified | 925 | 53.3 | 6.4 | 40.3 |

| Nutri-Score profile D 5 | ||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 213 | 85.5 | 1.4 | 13.2 |

| Breakfast cereals | 172 | 62.2 | 19.2 | 18.6 |

| Salty snacks | 1263 | 86.7 | 4.6 | 8.7 |

| Cookies | 585 | 52.5 | 7.7 | 39.8 |

| Flour | 60 | 43.3 | 15.0 | 41.7 |

| Breads | 80 | 76.3 | 1.3 | 22.5 |

| Bars and pastries | 737 | 83.6 | 1.6 | 14.8 |

| Pastas | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 225 | 76.9 | 3.6 | 19.6 |

| Total WMPFs classified | 3340 | 76.9 | 5.1 | 18.1 |

| Nutri-Score profile E 6 | ||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Breakfast cereals | 10 | 70.0 | 0.0 | 30.0 |

| Salty snacks | 186 | 83.9 | 7.0 | 9.1 |

| Cookies | 963 | 72.8 | 3.6 | 23.6 |

| Flour | 48 | 16.7 | 2.1 | 81.3 |

| Breads | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Bars and pastries | 769 | 87.7 | 2.0 | 10.4 |

| Pastas | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 7 | 0.0 | 42.9 | 57.1 |

| Total WMPFs classified | 1986 | 77.8 | 3.4 | 18.8 |

| Product Category | WMPFs with Healthy Nutri-Score Profile 1 | WMPFs with Unhealthy Nutri-Score Profile 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SE Area | Low SE Area | GM ratio 3 (95%CI) | High SE Area | Low SE Area | GM Ratio 3 (95%CI) | |||||

| n | GM (95%CI) | n | GM (95%CI) | n | GM (95%CI) | n | GM (95%CI) | |||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 102 | 0.76 (0.61, 0.94) | 36 | 0.52 (0.47, 0.57) | 1.46 (1.15, 1.86) | 221 | 0.80 (0.72, 0.88) | 132 | 0.63 (0.55, 0.73) | 1.26 (1.06, 1.49) |

| Breakfast cereals | 33 | 0.60 (0.43, 0.82) | 15 | 0.37 (0.33, 0.42) | 1.59 (1.14, 2.23) | 214 | 0.71 (0.63, 0.80) | 125 | 0.47 (0.43, 0.52) | 1.51 (1.29, 1.77) |

| Salty snacks | 40 | 1.31 (1.00, 1.73) | - | - | - | 823 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.03) | 733 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) | 1.09 (0.99, 1.21) |

| Cookies | 45 | 1.04 (0.74, 1.45) | 11 | 0.35 (0.33, 0.36) | 3.01 (2.15, 4.21) | 1112 | 0.84 (0.66, 1.06) | 591 | 0.55 (0.49, 0.62) | 1.53 (1.18, 1.99) |

| Flour | 56 | 0.21 (0.17, 0.25) | 29 | 0.13 (0.10, 0.17) | 1.60 (1.16, 2.23) | 134 | 0.48 (0.43, 0.53) | 70 | 0.41 (0.36, 0.46) | 1.18 (1.01, 1.38) |

| Breads | 232 | 0.45 (0.36, 0.56) | 69 | 0.35 (0.34, 0.37) | 1.26 (1.00, 1.59) | 145 | 0.51 (0.39, 0.68) | 56 | 0.43 (0.40, 0.46) | 1.20 (0.90, 1.60) |

| Cereal bars, sweet breads, and pastries | 17 | 1.13 (0.88, 1.45) | - | - | - | 993 | 0.75 (0.71, 0.80) | 558 | 0.68 (0.65, 0.72) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19) |

| Pastas | 334 | 0.35 (0.20, 0.62) | 181 | 0.13 (0.12, 0.14) | 2.66 (1.50, 4.72) | 14 | 1.34 (0.54, 3.30) | - | - | - |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 88 | 0.51 (0.34, 0.75) | 25 | 0.26 (0.21, 0.33) | 1.93 (1.22, 3.05) | 223 | 0.42 (0.35, 0.50) | 107 | 0.31 (0.29, 0.33) | 1.34 (1.11, 1.62) |

| Total | 947 | 0.47 (0.34, 0.65) | 366 | 0.20 (0.18, 0.23) | 2.30 (1.60, 3.30) | 3879 | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) | 2372 | 0.64 (0.59, 0.71) | 1.20 (1.05, 1.37) |

| Product Category | WMPFs with Healthy Nutri-Score Profile 1 | WMPFs with Unhealthy Nutri-Score Profile 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SE Area | Low SE Area | GM Ratio 3 | High SE Area | Low SE Area | GM Ratio 3 | |||||

| n | GM (95%CI) | n | GM (95%CI) | (95%CI) | n | GM (95%CI) | n | GM (95%CI) | (95%CI) | |

| Supermarkets | ||||||||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 91 | 1.41 (0.52, 3.84) | 21 | 0.62 (0.58, 0.66) | 2.28 (0.84, 6.21) | 110 | 1.20 (0.57, 2.54) | 38 | 0.57 (0.56, 0.58) | 2.12 (1.00, 4.46) |

| Breakfast cereals | 27 | 2.62 (2.18, 3.14) | 10 | 1.67 (1.64, 1.70) | 1.57 (1.31, 1.88) | 174 | 2.80 (2.31, 3.41) | 72 | 1.32 (0.93, 1.86) | 2.13 (1.43, 3.16) |

| Salty snacks | 32 | 1.62 (1.39, 1.88) | - | - | - | 222 | 1.45 (1.17, 1.80) | 103 | 1.08 (0.96, 1.21) | 1.35 (1.05, 1.72) |

| Cookies | 38 | 2.53 (1.68, 3.80) | - | - | - | 495 | 2.55 (1.80, 3.62) | 44 | 0.92 (0.92, 0.92) | 2.79 (1.96, 3.96) |

| Flour | 52 | 1.70 (1.36, 2.13) | 16 | 0.65 (0.24, 1.78) | 2.62 (0.94, 7.35) | 102 | 1.80 (1.33, 2.43) | 29 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 1.91 (1.41, 2.60) |

| Breads | 106 | 2.19 (1.82, 2.65) | 16 | 1.56 (1.53, 1.60) | 1.40 (1.16, 1.69) | 77 | 1.80 (1.54, 2.10) | 23 | 1.34 (0.95, 1.87) | 1.35 (0.93, 1.96) |

| Cereal bars, sweet breads, and pastries | 9 | 1.57 (1.16, 2.11) | - | - | - | 184 | 1.53 (1.32, 1.79) | 56 | 1.13 (1.11, 1.15) | 1.36 (1.17, 1.59) |

| Pastas | 277 | 1.44 (0.48, 4.33) | 45 | 0.33 (0.29, 0.39) | 4.33 (1.43, 13.14) | 14 | 2.98 (0.90, 9.87) | - | - | - |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 60 | 1.61 (1.02, 2.53) | 8 | 1.04 (0.82, 1.32) | 1.55 (0.93, 2.59) | 94 | 1.24 (0.96, 1.60) | 9 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 1.25 (0.96, 1.62) |

| Total | 692 | 1.67 (0.89, 3.10) | 116 | 0.63 (0.57, 0.69) | 2.65 (1.41, 4.97) | 1473 | 1.93 (1.49, 2.49) | 399 | 1.03 (0.95, 1.13) | 1.86 (1.42, 2.44) |

| Independently owned grocery stores/convenience stores | ||||||||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 11 | 0.56 (0.27, 1.17) | 12 | 0.44 (0.33, 0.58) | 1.29 (0.59, 2.84) | 63 | 0.77 (0.60, 0.99) | 50 | 0.51 (0.36, 0.74) | 1.50 (0.96, 2.34) |

| Breakfast cereals | 6 | 0.81 (0.80, 0.82) | 5 | 1.13 (0.75, 1.71) | 0.71 (0.47, 1.07) | 22 | 1.02 (0.65, 1.59) | 49 | 0.92 (0.64, 1.32) | 1.10 (0.62, 1.96) |

| Salty snacks | 7 | 0.56 (0.33, 0.94) | - | - | - | 236 | 0.75 (0.59, 0.95) | 156 | 0.88 (0.69, 1.12) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.19) |

| Cookies | 5 | 0.76 (0.63, 0.92) | - | - | - | 266 | 0.73 (0.66, 0.80) | 188 | 0.84 (0.75, 0.94) | 0.86 (0.74, 1.00) |

| Flour | - | - | 13 | 0.55 (0.32, 0.95) | - | 24 | 0.40 (0.25, 0.63) | 37 | 0.43 (0.33, 0.55) | 0.93 (0.55, 1.59) |

| Breads | 37 | 1.40 (1.27, 1.53) | 11 | 1.35 (1.23, 1.49) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | 27 | 1.31 (1.27, 1.35) | 11 | 1.34 (1.09, 1.65) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.20) |

| Cereal bars, sweet breads, and pastries | 5 | 0.45 (0.32, 0.64) | - | - | - | 295 | 0.76 (0.68, 0.86) | 110 | 0.82 (0.73, 0.92) | 0.93 (0.79, 1.09) |

| Pastas | 20 | 0.30 (0.27, 0.33) | 81 | 0.26 (0.23, 0.28) | 1.17 (1.01, 1.35) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 11 | 0.77 (0.65, 0.92) | 11 | 0.79 (0.73, 0.86) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) | 44 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 29 | 1.02 (0.88, 1.18) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.16) |

| Total | 102 | 0.73 (0.54, 1.01) | 0.39 (0.31, 0.48) | 1.90 (1.29, 2.79) | 977 | 0.76 (0.68, 0.86) | 630 | 0.80 (0.73, 0.88) | 0.95 (0.81, 1.11) | |

| Neighborhood corner store | ||||||||||

| Ready-to-eat foods | - | - | - | - | - | 48 | 0.53 (0.48, 0.57) | 44 | 0.50 (0.48, 0.52) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) |

| Breakfast cereals | - | - | - | - | - | 18 | 0.55 (0.41, 0.75) | - | - | - |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | 365 | 0.52 (0.50, 0.54) | 474 | 0.51 (0.50, 0.52) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

| Cookies | - | - | 6 | 0.64 (0.62, 0.66) | - | 351 | 0.61 (0.60, 0.62) | 359 | 0.65 (0.63, 0.67) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) |

| Flour | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 0.52 (0.42, 0.65) | - | - | - |

| Breads | 89 | 1.40 (1.32, 1.49) | 42 | 1.23 (1.11, 1.35) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.28) | 41 | 1.30 (1.17, 1.45) | 22 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 1.29 (1.13, 1.46) |

| Cereal bars, sweet breads, and pastries | - | - | - | - | - | 514 | 0.64 (0.62, 0.67) | 392 | 0.64 (0.61, 0.67) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| Pastas | 37 | 0.32 (0.31, 0.33) | 55 | 0.32 (0.31, 0.33) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 17 | 0.88 (0.78, 0.98) | 6 | 0.81 (0.79, 0.83) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.22) | 84 | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 44 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19) |

| Total | 143 | 0.91 (0.75, 1.09) | 109 | 0.58 (0.47, 0.72) | 1.55 (1.17, 2.05) | 1429 | 0.63 (0.61, 0.64) | 1335 | 0.60 (0.59, 0.61) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) |

| Product Category | WMPFs with Healthy Nutri-Score Profile 1 | WMPFs with Unhealthy Nutri-Score Profile 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SE Area | Low SE Area | Difference (95%CI) 3 | High SE Area | Low SE Area | Difference (95%CI) 3 | |||||

| n | % (95%CI) | n | % (95%CI) | n | % (95%CI) | n | % (95%CI) | |||

| Ready-to-eat foods | 102 | 21.6 (17.1, 26.9) | 36 | 19.4 (10.9, 32.4) | 2.1 (−9.7, 13.9) | 221 | 10.0 (5.5, 17.2) | 132 | 2.3 (0.4, 11.1) | 7.7 (0.9, 14.5) |

| Breakfast cereals | 33 | 66.7 (52.8, 78.1) | 15 | 66.7 (54.9, 76.6) | 0 (−16.9, 16.9) | 214 | 53.7 (47.5, 59.8) | 125 | 64.8 (57.1, 71.8) | −11.1 (−20.7, −1.4) |

| Salty snacks | 40 | 30.0 (11.3, 59.0) | - | - | - | 823 | 7.4 (4.2, 12.8) | 733 | 3.3 (2.4, 4.4) | 4.1 (−0.1, 8.4) |

| Cookies | 45 | 51.1 (37.9, 64.1) | 11 | 18.2 (4.0, 54.4) | 32.9 (4.6, 61.3) | 1112 | 15.1 (9.6, 23.0) | 591 | 7.4 (5.8, 9.4) | 7.7 (0.8, 14.5) |

| Flour | 56 | 62.5 (52.7, 71.3) | 29 | 55.2 (37.4, 71.7) | 7.3 (−14.8, 29.4) | 134 | 36.6 (28.1, 45.9) | 70 | 40.0 (29.1, 51.9) | −3.4 (−18.1, 11.2) |

| Breads | 232 | 57.8 (48.3, 66.7) | 69 | 53.6 (45.7, 61.4) | 4.1 (−12.8, 27.5) | 145 | 37.2 (30.0, 45.1) | 56 | 17.9 (11.0, 27.8) | 19.4 (8.0, 30.7) |

| Cereal bars, sweet breads, and pastries | 17 | 23.5 (2.9, 76.1) | - | - | - | 993 | 22.2 (18.2, 26.7) | 558 | 17.4 (12.9, 23.0) | 4.8 (−1.8, 11.4) |

| Pastas | 334 | 43.4 (30.9, 56.8) | 181 | 70.2 (55.4, 81.7) | −26.8 (−45.6, −7.9) | 14 | 7.1 (0.7, 44.0) | - | - | - |

| Maize tortillas and tortilla products | 88 | 72.7 (63.0, 80.7) | 25 | 40.0 (21.7, 61.6) | 32.7 (9.9, 55.6) | 223 | 40.4 (30.9, 50.5) | 107 | 18.7 (11.1, 29.7) | 21.7 (8.1, 35.2) |

| Total WMPFs | 947 | 48.7 (41.1, 56.4) | 366 | 56.6 (46.3, 66.5) | −7.9 (−20.8, 4.9) | 3879 | 20.1 (14.8, 26.5) | 2372 | 12.9 (9.2, 17.9) | 7.2 (−0.1, 14.4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Cruz-Casarrubias, C.; Pacheco-Miranda, S.; Marrón-Ponce, J.A.; Quezada, A.D.; García-Guerra, A.; Donovan, J. Access to Healthy Wheat and Maize Processed Foods in Mexico City: Comparisons across Socioeconomic Areas and Store Types. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061173

Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Cruz-Casarrubias C, Pacheco-Miranda S, Marrón-Ponce JA, Quezada AD, García-Guerra A, Donovan J. Access to Healthy Wheat and Maize Processed Foods in Mexico City: Comparisons across Socioeconomic Areas and Store Types. Nutrients. 2022; 14(6):1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061173

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Gaxiola, Ana Cecilia, Carlos Cruz-Casarrubias, Selene Pacheco-Miranda, Joaquín Alejandro Marrón-Ponce, Amado David Quezada, Armando García-Guerra, and Jason Donovan. 2022. "Access to Healthy Wheat and Maize Processed Foods in Mexico City: Comparisons across Socioeconomic Areas and Store Types" Nutrients 14, no. 6: 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061173

APA StyleFernández-Gaxiola, A. C., Cruz-Casarrubias, C., Pacheco-Miranda, S., Marrón-Ponce, J. A., Quezada, A. D., García-Guerra, A., & Donovan, J. (2022). Access to Healthy Wheat and Maize Processed Foods in Mexico City: Comparisons across Socioeconomic Areas and Store Types. Nutrients, 14(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061173