The Relationship between Fatty Acids and the Development, Course and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

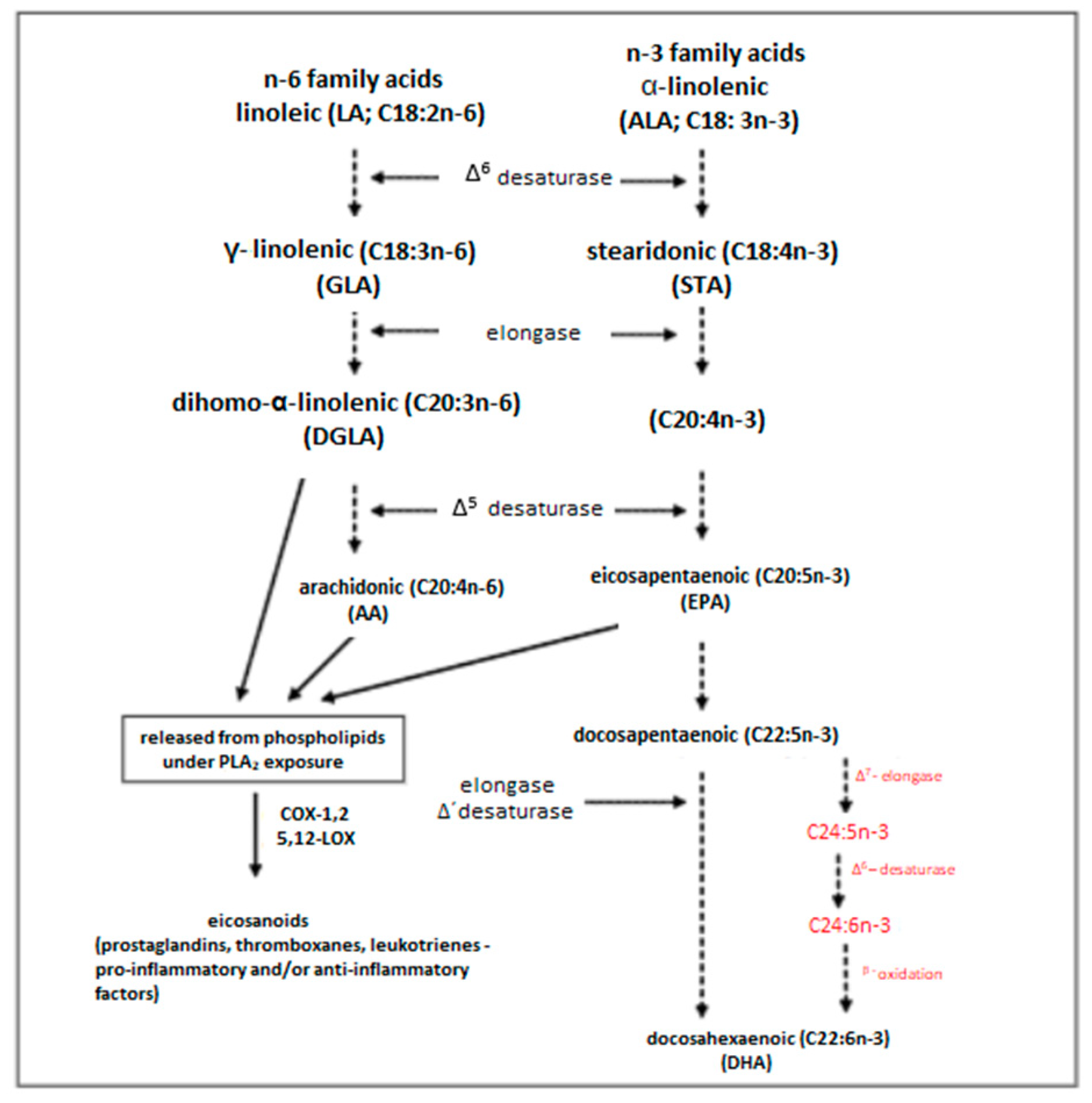

3. Classification of Fatty Acids

4. The Involvement of Fatty Acids in the Development of RA

5. The Role of Fatty Acids in the Treatment of RA

6. Fatty Acids and the Quality of Life

7. Conclusions and Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Gibofsky, A. Overview of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, I.C.; Tan, R.; Stahl, D.; Steer, S.; Lewis, C.M.; Cope, A.P. The protective effect of alcohol on developing rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2013, 52, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisell, T.; Saevarsdottir, S.; Askling, J. Family history of rheumatoid arthritis: An old concept with new developments. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlson, E.W.; Deane, K. Environmental and gene-environment interactions and risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 38, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, B.A.; Bang, S.Y.; Chowdhury, M.; Lee, H.-S.; Kim, J.H.; Charles, P.; Venables, P.; Bae, S.-C. Smoking, the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope and ACPA fine-specificity in Koreans with rheumatoid arthritis: Evidence for more than one pathogenic pathway linking smoking to disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka-Stążka, P. Rola Kwasu Chinaldinowego w Reumatoidalnym Zapaleniu Stawleni. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe, D.; Discacciati, A.; Orsini, N.; Wolk, A. Cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014, 16, R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Xiang, C.; Cai, Q.; Wei, X.; He, J. Alcohol consumption as a preventive factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1962–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhou, C.H.; Pei, H.J.; Zhou, X.L.; Li, L.H.; Wu, Y.J.; Hui, R.T. Fish consumption and incidence of heart failure: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Chin. Med. J. 2013, 126, 942–948. [Google Scholar]

- Rudkowska, I.; Ouellette, C.; Dewailly, E.; Hegele, R.A.; Boiteau, V.; Dube-Linteau, A.; Abdous, B.; Proust, F.; Giguere, Y.; Julien, P.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids, polymorphisms and lipid- related cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Inuit population. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazaq, M.; Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Effect of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on arthritic pain: A systematic review. Nutrition 2017, 39–40, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senftleber, N.K.; Nielsen, S.M.; Andersen, J.R.; Bliddal, H.; Tarp, S.; Lauritzen, L.; Furst, D.E.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E.; Lyddiatt, A.; Christensen, R. Marine oil supplements for arthritis pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Nutrients 2017, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Influence of marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on immune function and a systematic review of their effects on clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, S171–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Nutrition or pharmacology? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbige, L.S. Fatty acids, the immune response, and autoimmunity: A question of n-6 essentiality and the balance between n-6 and n-3. Lipids 2003, 38, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist, H.M.; Gjertsson, I.; Andersson, S.; Calder, P.C.; Bärebring, L. Influence of blue mussel (Mytilusedulis) intake on fatty acid composition in erythrocytes and plasma phospholipids and serum metabolites in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2019, 150, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, H.M.; Gjertsson, I.; Eneljung, T.; Winkvist, A. Influence of blue mussel (Mytilusedulis) intake on disease activity in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: The MIRA randomized cross-over dietary intervention. Nutrients 2018, 10, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawczynski, C.; Dittrich, M.; Neumann, T.; Goetze, K.; Welzel, A.; Oelzner, P.; Völker, S.; Schaible, A.M.; Troisi, F.; Thomas, L.; et al. Docosahexaenoic acid in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized cross-over study with microalgae vs. sunflower oil. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudman, S.M.; James, M.J.; Spargo, L.D.; Metcalf, R.G.; Sullivan, T.; Rischmueller, M.; Flabouris, K.; Wechalekar, M.D.; Lee, A.T.; Cleland, L.G. Fish oil in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis: A randomised, double-blind controlled trial within algorithm-based drug use. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Xing, G.; Hu, X.; Yang, L.; Li, D. Lipid extract from hard-shelled mussel (Mytiluscoruscus) improves clinical conditions of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2015, 7, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, A.; Shim, S.C.; Lee, J.H.; Choe, J.Y.; Ahn, H.; Choi, C.B.; Sung, Y.K.; Bae, S.C. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design multicenter study in Korea. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawczynski, C.; Hackermeier, U.; Viehweger, M.; Stange, R.; Springer, M.; Jahreis, G. Incorporation of n-3 PUFA and γ-linolenic acid in blood lipids and red blood cell lipids together with their influence on disease activity in patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis—A randomized controlled human intervention trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2011, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadori, B.; Uitz, E.; Thonhofer, R.; Trummer, M.; Pestemer-Lach, I.; McCarty, M.; Krejs, G.J. Omega-3 Fatty acids infusions as adjuvant therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral. Nutr. 2010, 34, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, S.; Ghorbanihaghjo, A.; Alizadeh, S.; Rashtchizadeh, N.; Argani, H.; Khabazzi, A.R.; Hajialilo, M.; Bahreini, E. Fish oil supplementation decreases serum soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand/osteoprotegerin ratio in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 43, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawczynski, C.; Schubert, R.; Hein, G.; Müller, A.; Eidner, T.; Vogelsang, H.; Basu, S.; Jahreis, G. Long-term moderate intervention with n-3 long-chain PUFA-supplemented dairy products: Effects on pathophysiological biomarkers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryaeian, N.; Shahram, F.; Djalali, M.; Eshragian, M.R.; Djazayeri, A.; Sarrafnejad, A.; Salimzadeh, A.; Naderi, N.; Maryam, C. Effect of conjugated linoleic acids, vitamin E and their combination on the clinical outcome of Iranian adults with active rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 12, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.C.; Jung, W.J.; Lee, E.J.; Yu, R.; Sung, M.K. Effects of antioxidant supplements intervention on the level of plasma inflammatory molecules and disease severity of rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryaeian, N.; Shahram, F.; Djalali, M.; Eshragian, M.R.; Djazayeri, A.; Sarrafnejad, A.; Naderi, N.; Chamari, M.; Fatehi, F.; Zarei, M. Effect of conjugated linoleic acid, vitamin E and their combination on lipid profiles and blood pressure of Iranian adults with active rheumatoid arthritis. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarraga, B.; Ho, M.; Youssef, H.M.; Hill, A.; McMahon, H.; Hall, C.; Ogston, S.; Nuki, G.; Belch, J.J. Cod liver oil (n-3 fatty acids) as an non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug sparing agent in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2008, 47, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbert, A.A.; Kondo, C.R.; Almendra, C.L.; Matsuo, T.; Dichi, I. Supplementation of fish oil and olive oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition 2005, 21, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remans, P.H.; Sont, J.K.; Wagenaar, L.W.; Wouters-Wesseling, W.; Zuijderduin, W.M.; Jongma, A.; Breedveld, F.C.; Van Laar, J.M. Nutrient supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids and micronutrients in rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical and biochemical effects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundrarjun, T.; Komindr, S.; Archararit, N.; Dahlan, W.; Puchaiwatananon, O.; Angthararak, S.; Udomsuppayakul, U.; Chuncharunee, S. Effects of n-3 fatty acids on serum interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor p55 in active rheumatoid arthritis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2004, 32, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volker, D.; Fitzgerald, P.; Major, G.; Garg, M. Efficacy of fish oil concentrate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 27, 2343–2346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Comi, D.; Boccassini, L.; Muzzupappa, S.; Turiel, M.; Panni, B.; Salvaggio, A. Diet therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. A controlled double-blind study of two different dietary regimens. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 29, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurier, R.B.; Rossetti, R.G.; Jacobson, E.W.; DeMarco, D.M.; Liu, N.Y.; Temming, J.E.; White, B.M.; Laposata, M. Gamma-Linolenic acid treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39, 1808–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, L.J.; Boyce, E.G.; Zurier, R.B. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with blackcurrant seed oil. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1994, 33, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, P.; Wouters, C.; Nijs, J.; Jiang, Y.; Dequeker, J. Long-term effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in active rheumatoid arthritis. A 12-month, double-blind, controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 1994, 37, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.S.; Morley, K.D.; Belch, J.J. Effects of fish oil supplementation on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug requirement in patients with mild rheumatoid arthritis—A double-blind placebo controlled study. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1993, 32, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, L.J.; Boyce, E.G.; Zurier, R.B. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with gammalinolenic acid. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993, 119, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen-Kragh, J.; Lund, J.A.; Riise, T.; Finnanger, B.; Haaland, K.; Finstad, R.; Mikkelsen, K.; Forre, O. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and naproxen treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1992, 19, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Espersen, G.T.; Grunnet, N.; Lervang, H.H.; Nielsen, G.L.; Thomsen, B.S.; Faarvang, K.L.; Dyerberg, J.; Ernst, E. Decreased interleukin-1beta levels in plasma from rheumatoid arthritis patients after dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Clin. Rheumatol. 1992, 11, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G.L.; Faarvang, K.L.; Thomsen, B.S.; Teglbjaerg, K.L.; Jensen, L.T.; Hansen, T.M.; Lervang, H.H.; Schmidt, E.B.; Dyerberg, J.; Ernst, E. The effects of dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double blind trial. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 1992, 22, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzeski, M.; Madhok, R.; Capell, H.A. Evening primrose oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and side-effects of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1991, 30, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Tempel, H.; Tulleken, J.E.; Limburg, P.C.; Muskiet, F.A.; van Rijswijk, M.H. Effects of fish oil supplementation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1990, 49, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, J.M.; Lawrence, D.A.; Jubiz, W.; DiGiacomo, R.; Rynes, R.; Bartholomew, L.E.; Sherman, M. Dietary fish oil and olive oil supplementation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Clinical and immunologic effects. Arthritis. Rheum. 1990, 33, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulleken, J.E.; Limburg, P.C.; Muskiet, F.A.; van Rijswgk, M.H. Vitamin E status during dietary fish oil supplementation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33, 1416–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaro, M.; Altomonte, L.; Zoli, A.; Mirone, L.; De Sole, P.; Di Mario, G.; Lippa, S.; Oradei, A. Influence of diet with different lipid composition on neutrophil chemiluminescence and disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1988, 47, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, J.M.; Bigauoette, J.; Michalek, A.V.; Timchalk, M.A.; Lininger, L.; Rynes, R.I.; Huyck, C.; Zieminski, J.; Bartholomew, L.E. Effects of manipulation of dietary fatty acids on clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1985, 1, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeb, B.F.; Sautner, J.; Andel, I.; Rintelen, B. Intravenous application of omega-3 fatty acids in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. The ORA-1 trial. An open pilot study. Lipids 2006, 41, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, L.G.; Caughey, G.E.; James, M.J.; Proudman, S.M. Reduction of cardiovascular risk factors with longterm fish oil treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 33, 1973–1979. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, O.; Beringer, C.; Kless, T.; Lemmen, C.; Adam, A.; Wiseman, M.; Adam, P.; Klimmek, R.; Forth, W. Anti-inflammatory effects of a low arachidonic acid diet and fish oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2003, 23, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, J.M.; Lawrence, D.A.; Petrillo, G.F.; Litts, L.L.; Mullaly, P.M.; Rynes, R.I.; Stocker, R.P.; Parhami, N.; Greenstein, N.S.; Fuchs, B.R. Effects of high-dose fish oil on rheumatoid arthritis after stopping nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Clinical and immune correlates. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, M.A.; Kjeldsen-Kragh, J.; Bjerve, K.S.; Høstmark, A.T.; Førre, O. Changes in plasma phospholipid fatty acids and their relationship to disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with a vegetarian diet. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 72, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pullman-Mooar, S.; Laposata, M.; Lem, D.; Holman, R.T.; Leventhal, L.J.; DeMarco, D.; Zurier, R.B. Alteration of the cellular fatty acid profile and the production of eicosanoids in human monocytes by gamma-linolenic acid. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäntti, J.; Nikkari, T.; Solakivi, T.; Vapaatalo, H.; Isomäki, H. Evening primrose oil in rheumatoid arthritis: Changes in serum lipids and fatty acids. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1989, 48, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, L.G.; French, J.K.; Betts, W.H.; Murphy, G.A.; Elliott, M.J. Clinical and biochemical effects of dietary fish oil supplements in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1988, 15, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Belch, J.J.F.; Madhok, A.R.; O’Dowd, A.; Sturrock, R.D. Effects of altering dietary essential fatty acids on requirements for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A double blind placebo controlled study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1988, 47, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, J.M.; Jubiz, W.; Michalek, A.; Rynes, R.I.; Bartholomew, L.E.; Bigaouette, J.; Timchalk, M.; Beeler, D.; Lininger, L. Fish-oil fatty acid supplementation in active rheumatoid arthritis. A double-blinded, controlled, crossover study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1987, 106, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K.; Lie, S.A.; Bjørndal, B.; Berge, R.K.; Svardal, A.; Brun, J.G.; Bolstad, A.I. Lipid, fatty acid, carnitine- and choline derivative profiles in rheumatoid arthritis outpatients with different degrees of periodontal inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonem, A.M.; Käkelä, R.; Lehenkari, P.; Huhtakangas, J.; Turunen, S.; Joukainen, A.; Kaarianen, T.; Paakkonen, T.; Kroger, H.; Naiminen, P. Distinct fatty acid signatures in infrapatellar fat pad and synovial fluid of patients with osteoarthritis versus rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasriati, F.; Hidayat, R.; Budiman, B.; Rinaldi, I. Correlation between tumor necrosis factor-α levels, free fatty acid levels, and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 levels in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Open Rheumatol. J. 2018, 12, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablo, P.; Romaguera, D.; Fisk, H.L.; Calder, P.C.; Quirke, A.-M.; Cartwright, A.J.; Panico, S.; Mattiello, A.; Gavrila, D.; Navarro, C.; et al. High erythrocyte levels of the n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid linoleic acid are associated with lower risk of subsequent rheumatoid arthritis in a southern European nested case–Control study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K.; Lie, S.A.; Kjellevold, M.; Dahl, L.; Brun, J.G.; Bolstad, A.I. Marine ω-3, vitamin D levels, disease outcome and periodontal status in rheumatoid arthritis outpatients. Nutrition 2018, 55–56, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bärebring, L.; Winkvist, A.; Gjertsson, I.; Lindqvist, H.M. Poor dietary quality is associated with increased inflammation in swedish patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, R.W.; Demoruelle, M.K.; Deane, K.D.; Weisman, M.H.; Buckner, J.H.; Gregersen, P.K.; Mikuls, T.R.; O’Dell, J.R.; Keating, R.M.; Fingerlin, E.T.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids are associated with a lower prevalence of autoantibodies in shared epitope-positive subjects at risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, L.; Fisk, H.L.; Calder, P.C.; Filer, A.; Raza, K.; Buckley, C.; McInnes, I.; Taylor, P.; Fisher, B. Plasma levels of eicosapentaenoic acid are associated with anti-TNF responsiveness in rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit the etanercept-driven rise in Th17 cell differentiation in vitro. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, R.W.; Young, K.A.; Zerbe, G.O.; Demoruelle, M.K.; Weisman, M.H.; Buckner, J.H.; Gregersen, P.K.; Mikuls, T.R.; O’Dell, J.R.; Keating, R.M.; et al. Lower omega-3 fatty acids are associated with the presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide autoantibodies in a population at risk for future rheumatoid arthritis: A nested case-control study. Rheumatology 2016, 55, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Carrio, J.; Alperi-López, M.; López, P.; Ballina-García, F.J.; Suárez, A. Non-Esterified fatty acids profiling in rheumatoid arthritis: Associations with clinical features and Th1 Response. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinska, M.K.; Ludwig, T.E.; Liebisch, G.; Zhang, R.; Siebert, H.-C.; Wilhelm, J.; Kaesser, U.; Dettmeyer, R.B.; Klein, H.; Ishaque, B.; et al. Articular joint lubricants during osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis display altered levels and molecular species. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, D.; Wallin, A.; Bottai, M.; Askling, J.; Wolk, A. Long-term intake of dietary long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective cohort study of women. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1949–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.L.; Park, Y. The association between n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid levels in erythrocytes and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in Korean women. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 63, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Satoi, K.; Sato-Mito, N.; Kaburagi, T.; Yoshino, H.; Higaki, M.; Nishimoto, K.; Sato, K. Nutritional status in relation to adipokines and oxidative stress is associated with disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition 2012, 28, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormseth, M.J.; Swift, L.L.; Fazio, S.; Linton, M.F.; Chung, C.P.; Raggi, P.; Rho, Y.H.; Solus, J.; Oeser, A.; Bian, A.; et al. Free fatty acids are associated with insulin resistance but not coronary artery atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis 2011, 219, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Elkan, A.C.; Håkansson, N.; Frostegård, J.; Cederholm, T.; Hafström, I. Rheumatoid cachexia is associated with dyslipidemia and low levels of atheroprotective natural antibodies against phosphorylcholine but not with dietary fat in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosell, M.; Wesley, A.M.; Rydin, K.; Klareskog, L.; Alfredsson, L. Dietary fish and fish oil and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Epidemiology 2009, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das Gupta, A.B.; Hossain, A.K.; Islam, M.H.; Dey, S.R.; Khan, A.L. Role of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation with indomethacin in suppression of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Bangladesh Med. Res. Counc. Bull. 2009, 35, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.; Stripp, C.; Klarlund, M.; Olsen, S.F.; Tjønneland, A.M.; Frisch, M. Diet and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in a prospective cohort. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenwald, J.; Graubaum, H.J.; Hansen, K.; Grube, B. Efficacy and tolerability of a combination of Lyprinol and high concentrations of EPA and DHA in inflammatory rheumatoid disorders. Adv. Ther. 2004, 21, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furse, R.K.; Rossetti, R.G.; Zurier, R.B. Gammalinolenic acid, an unsaturated fatty acid with anti-inflammatory properties, blocks amplification of IL-1 beta production by human monocytes. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linos, A.; Kaklamani, V.G.; Kaklamani, E.; Koumantaki, Y.; Giziaki, E.; Papazoglou, S.; Mantzoros, C.S. Dietary factors in relation to rheumatoid arthritis: A role for olive oil and cooked vegetables? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 1077–1082, Erratum in: Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.A.; Thoen, J.; Rustan, A.C.; Førre, O.; Kjeldsen-Kragh, J. Changes in plasma free fatty acid concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis patients during fasting and their effects upon T-lymphocyte proliferation. Rheumatology 1999, 38, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shapiro, J.A.; Koepsell, T.D.; Voigt, L.F.; Dugowson, C.E.; Kestin, M.; Nelson, J.L. Diet and rheumatoid arthritis in women: A possible protective effect of fish consumption. Epidemiology 1996, 7, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarò, M.; Zoli, A.; Altomonte, L.; Mirone, L.; De Sole, P.; Di Mario, G.; De Leo, E. Effect of fish oil on neutrophil chemiluminescence induced by different stimuli in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1992, 51, 877–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsson, L.; Lindgärde, F.; Manthorpe, R.; Akesson, B. Correlation of fatty acid composition of adipose tissue lipids and serum phosphatidylcholine and serum concentrations of micronutrients with disease duration in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1990, 49, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, R.I.; Weinblatt, M.; Robin, J.L.; Ravalese, I.J.; Hoover, R.L.; House, F.; Coblyn, J.S.; Fraser, P.A.; Spur, B.W.; Robinson, D.R.; et al. Effects of dietary supplementation with marine fish oil on leukocyte lipid mediator generation and function in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987, 30, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klickstein, L.B.; Shapleigh, C.; Goetzl, E. Lipoxygenation of arachidonic acid as a source of polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemotactic factors in synovial fluid and tissue in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 1980, 66, 116670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, B.H. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 796–798. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist. 2013. Available online: http://www.casp-uk.net/checklists (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Jarosz, M. Normy Żywienia dla Populacji Polski; IŻŻ: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.M.; Burdge, G. Long-chain n-3 PUFA: Plant v. marine sources. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2006, 65, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arterburn, L.M.; Hall, E.B.; Oken, H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1467s–1476s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillwell, W.; Shaikh, S.R.; Zerouga, M.; Siddiqui, R.; Wassall, S.R. Docosahexaenoic acid affects cell signaling by altering lipid rafts. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2005, 45, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. Importance of the omega-6/omega-3 balance in health and disease: Evolutionary aspects of diet. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 102, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, M.H.; Dorian, P.; Verma, S. Fish oil supplementation and arrhythmias. JAMA 2005, 294, 2165–2166. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, A.; Moe, S. Review of the effects of omega-3 supplementation in dialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, H.; Zadravec, D.; Martin, P.G.; Jacobsson, A. The key roles of elongases and desaturases in mammalian fatty acid metabolism: Insights from transgenic mice. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010, 49, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, A. Very long-chain fatty acids: Elongation, physiology and related disorders. J. Biochem. 2012, 152, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Nanri, A.; Matsushita, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Ohta, M.; Sato, M.; Mizoue, T. Dietary intakes of alpha-linolenic and linoleic acids are inversely associated with serum C-reactive protein levels among Japanese men. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathias, R.A.; Vergara, C.; Gao, L.; Rafaels, N.; Hand, T.; Campbell, M.; Bickel, C.; Ivester, P.; Sergeant, S.; Barnes, K.C.; et al. FADS genetic variants and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism in a homogeneous island population. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2766–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriens, C.; Mohan, C.; Karp, D.R. Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Quality of Life in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Available online: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/impact-of-omega-3-fatty-acids-on-quality-of-life-in-systemic-lupus-erythematosus/ (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A.; Anderson, J.M.; Maresh, C.M.; Tiberio, D.P.; Joyce, E.M.; Messinger, B.N.; French, D.N.; Rubin, M.R.; Gomez, A.L.; et al. Effect of a cetylated fatty acid topical cream on functional mobility and quality of life of patients with osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 31, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

| Lp. | Author Year | Study Design | Study Group | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lindqvist HM et al., 2019 [17] | RCT | 39 RA women aged 25–65 years | CG: habitual diet (n = 19). IG: replacement of one meal per day, with a meal containing 75 g blue mussels or 75 g meat (n = 20). Duration 11 weeks, change between groups after 8 weeks of elimination. | GI patients differed in erythrocyte fatty acid profile compared to CG, with changes in the increase of omega-3 fatty acids: EPA and DHA at the group level. The fatty acid profile in plasma phospholipids and serum 1H NMR metabolites was not significantly different between diets. The change in the pattern of fatty acids in erythrocytes may be associated with a reduction in disease activity, although it cannot be excluded that factors other than omega-3 fatty acids potentiate this effect. |

| 2 | Lindqvist HM et al., 2018 [18] | RCT | 39 RA women aged 25–65 years | CG: habitual diet (n = 19). IG: replacement of one meal per day, with a meal containing 75 g blue mussels or 75 g meat (n = 20). Duration 11 weeks, change between groups after 8 weeks of elimination. | A reduction in DAS28-CRP (p = 0.048) but not DAS28 was observed in the IG group. Blue mussel consumption was associated with moderate to good response to EULAR criteria and a reduction in RA symptoms. Blood lipid levels were unchanged. |

| 3 | Dawczynski C et al., 2018 [19] | RCT | 38 RA patients aged 59.5 ± 12.4 years | IG: (n = 19) enriched with oil from the microalgae Schizochytrium sp. (2.1 g DHA/d) CG: (n = 19) with sunflower oil (placebo) Time: 10 weeks | In IG, daily DHA consumption led to a decrease in the sum of tender and swollen joints from 13.9 ± 7.4 to 9.9 ± 7.0 and the total DAS28 score from 4.3 ± 1.0 to 3.9 ± 1.2 in contrast to CG. An increase in LA and AA content in erythrocyte lipids was observed in the placebo group. In contrast, in the IG group the amount of DHA was doubled in EL, and the ratio of AA/EPA and AA/DHA decreased significantly. |

| 4 | Proudman SM et al., 2015 [20] | RCT | IG: 86 RA patients aged 56.1 ± 15.9 CG: 56 RA patients aged 55.5 ± 14.1 | IG: 5.5 g/d omega-3 FAs + EPA + DHA CG: 0.4 g/d omega-3 FAs + EPA + DHA | IG patients had lower DMARD triple therapy failure rate (HR = 0.28) (95% CI 0.12–0.63; p = 0.002), higher ACR first remission rate (HRs = 2.17) (95% CI 1.07–4.42; p = 0.03) compared to CG. No differences in DAS28 and mHAQ or adverse events between IG and CG. |

| 5 | Fu Y et al., 2015 [21] | RCT | 50 RA patients aged 28–75 years | IG: lipid extract from hard-shelled mussel (Mytilus coruscus) (HMLE) CG: Placebo Time: 6 months | The HMLE group showed significant improvement in DAS-28 disease activity score, clinical disease activity index (CDAI), decrease in TNF-α (tumour necrosis factor α), interleukin (IL)-1β and PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) after 6-month intervention. IL-10 was increased in both groups, significantly more in the HMLE group. |

| 6 | Park Y et al., 2013 [22] | RCT | IG: 41 RA patients aged 49.24 ± 10.46 CG: 40 RA patients aged 47.63 ± 8.78 | IG: 2.09 g EPA and 1.165 g DHA CG: sunflower oil with high oleic acid content. Time: 16 weeks | The IG group showed a significant increase in erythrocyte levels of omega-3 FAs and EPAs and a decrease in omega-6 FAs, 18: 2n6, 20: 4n6 and 18: 1n9 compared with the placebo group. Supplementation with n-3 PUFAs had no significant effect on the need for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), clinical symptoms of RA, or levels of cytokines, eicosanoids and bone turnover markers. In contrast, n-3 PUFA supplementation significantly reduced NSAID requirements and leukotriene B4 levels in patients who weighed more than 55 kg. |

| 7 | Dawczynski C et al., 2011 [23] | RCT | 54 RA patients and 6 patients with psoriatic arthritis in mean age 56 ± 13 years | I: 3.0 g omega-3 FAs/d; II: 3.2 g GLA/d III: 1.6 g omega-3 FAs + 1.8 g GLA/d; IV: 3.0 g olive oil Time: 12 weeks. | In group I, the AA/EPA ratio decreased from 6.5 ± 3.7 to 2.7 ± 2.1 in plasma lipids and from 25.1 ± 10.1 to 7.2 ± 4.7 in erythrocyte membranes (p ≤ 0.001). A strong increase in GLA and dihomo-γ-linolenic acid was observed in plasma lipids, cholesterol esters and erythrocyte membranes in groups II and III. |

| 8 | Bahadori B et al., 2010 [24] | RCT | 23 patients with moderate to severe RA | IG: 0.2 g fish oil emulsion/kg intravenously for 14 days, then 0.05 g fish oil/kg CG: 0.9% saline (placebo) intravenously for 14 days, then paraffin (placebo) taken orally as capsules. | The number of swollen joints was significantly lower in the omega-3 FA group compared with the placebo group after 1 week of infusion (p = 0.002) as well as after 2 weeks of infusion (p = 0.046). The number of tender joints also tended to be lower in the omega-3 FA group, although this did not reach statistical significance. Both the number of swollen and tender joints were significantly lower in the omega-3 FA group compared with the placebo group during and at the end of oral treatment. |

| 9 | Kolahi S et al., 2010 [25] | RCT | I: 40 RA female patients aged 50 (18–74) II: 43 RA female patients aged 50 (19–74) | I: fish oil 1 g/d II: no fish oil, conventional drugs Time: 3 months | In the fish oil supplementation group, osteoprotegerin levels increased, while sRANKL, TNF-alpha and the sRANKL/osteoprotegerin ratio decreased and there was a significant positive correlation between the sRANKL/osteoprotegerin ratio and TNF-alpha levels (r = 0.327, p = 0.040). |

| 10 | Dawczynski C et al., 2009 [26] | RCT | 39 RA patients aged 57.9 ± 10.8 years | IG: 40 g fat in the form of 200 g yogurt with 3–8% fat, 30 g cheese with about 50% fat in dry matter, and 20–30 g butter daily; 1.1 g a-linolenic acid, 0–7 g EPA, 0.1 g DPA and 0.4 g DHA. 50 mg/d AA CG: dairy products with comparable fat content, 70 mg/d AA Time: 12 weeks and an 8-week elimination phase in between. | In the IG group, we found that omega-3 FAs inhibited the immune response by significantly reducing the number of lymphocytes and monocytes. N-3 LC-PUFAs did not increase oxidative stress biomarkers, such as 8-iso-PGF(2alpha) and 15-keto-dihydro PGF(2alpha), and DNA damage, such as 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine. |

| 11 | Aryaeian N et al., 2009 [27] | RCT | Gr. P: 22 RA patients aged 47.95 ± 11.14 Gr. C: 22 RA patients aged 46.23 ± 13.07 Gr. E: 21 RA patients aged 49.33 ± 11.89 Gr. CE: 22 RA patients aged 43.77 ± 12.75 | C: CLAs 2.5 g equivalent to 2 g of a 50/50 mixture of cis 9-trans11 and trans 10-cis12 CLAs E: vitamin E 400 mg CE: CLAs and vitamin E at the above doses P: placebo. Time: 3 months | DAS28, pain and morning stiffness were significantly decreased in the Ci CE group compared with the P group (p < 0.05). Compared with baseline, ESR levels decreased significantly in groups C (p < or =0.05), E (p < or =0.05) and CE (p < or =0.001). The CE group had significantly lower ESR levels than the P group (p < 0.05) and a significantly lower white blood cell count compared with the other groups (p < 0.05). |

| 12 | Bae SC. et al., 2009 [28] | RCT | 20 RA patients with the mean age of 52.1 ± 10.3 years | I: quercetin + vitamin C (166 mg + 133 mg/capsule) II: alpha-lipoic acid (300 mg/capsule) III: placebo for 4 weeks (3 capsules/day). Time: 4 weeks with a 2-week break before starting the next supplementation. | There were no significant differences in serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines and CRP between the study groups. Disease severity scale scores were not significantly different between study groups, although quercetin supplementation tended to reduce the VAS. |

| 13 | Aryaeian N et al., 2008 [29] | RCT | Gr. P: 22 RA patients aged 47.95 ± 11.14 Gr. C: 22 RA patients aged 46.23 ± 13.07 Gr. E: 21 RA patients aged 49.33 ± 11.89 Gr. CE: 22 RA patients aged 43.77 ± 12.75 | C: CLAs 2.5 g equivalent to 2 g of a 50/50 mixture of cis 9-trans11 and trans 10-cis12 CLAs E: vitamin E 400 mg CE: CLAs and vitamin E at the above doses P: placebo. Time: 3 months | After supplementation, SBP levels decreased significantly in group C compared with groups E and P, and mean arterial pressure decreased significantly in groups C and CE. There were no significant differences in PGE2, triglycerides, cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, LDL/HDL, cholesterol/HDL, fasting blood sugar, CRP, arylesterase activity, and platelet count between groups. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate decreased in C, E and CE groups. |

| 14 | Galarraga B et al., 2008 [30] | RCT | IG: 49 RA patients in median age 58 years CG: 48 RA patients in median age 61 years | IG: 10 g cod liver oil containing 2.2 g omega-3 Fas CG: air-filled placebo capsules. Time: 9 months | Of the 49 patients, 19 (39%) in the cod liver oil group and 5 (10%) in the placebo group were able to reduce daily NSAID requirements by >30%. There were no differences between the groups in clinical parameters of RA disease activity or in observed side effects. |

| 15 | Berbert AA et al., 2005 [31] | RCT | 43 RA patients in mean age 49 ± 19 years | CG: soybean oil (placebo) IG1: 3 g/d omega-3 FAs from fish oil IG2: 3 g/d omega-3 FAs from fish oil + 9.6 mL olive oil. Time: 24 weeks | There was statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05) in IG1 and IG2 groups relative to CG in joint pain intensity, right and left hand grip strength at 12 and 24 w, duration of morning stiffness, onset of fatigue, Ritchie joint index for painful joints at 24 w, ability to bend to pick up clothing from the floor, and getting in and out of a car at 24 w. IG2 vs. CG showed additional improvement for duration of morning stiffness after 12 w, global patient assessment at 12 and 24 w, and from rheumatoid factor at 24 w. In addition, IG2 showed significant improvement in global patient assessment relative to IG1 at 12 w. |

| 16 | Remans PH et al., 2004 [32] | RCT | IG: 26 RA patients aged 52.97 ± 11.2 CG: 29 RA patients aged 59.57 ± 11.0 | IG: 1.4 g EPA, 0.211 g DHA, 0.5 g-GLA and micronutrients CG: placebo Time: 4 months | There was no significant change in the number of tender joints or other clinical parameters in any of the study groups compared with baseline. In patients receiving nutrient supplementation but not placebo, there was a significant increase in plasma levels of vitamin E (p = 0.015) and EPA, DHA, and docosapentaenoic acid with a decrease in AA levels (p = 0.01). |

| 17 | Sundrarjun T et al., 2004 [33] | RCT | I: 23 RA patients aged 46.2 ± 0.5 II: 23 RA patients aged 46.0 ± 0.5 III: 14 RA patients aged 48.6 ± 0.7 | I: low omega-6 FA diet + omega-3 FA supplement (fish oil), II: low omega-6 FA diet (placebo group) III: no special diet or intervention (control group). | At week 18, group I had significant decreases in linoleic acid, CRP, and sTNF-R p55 and significant increases in EPA and DHA compared with group III. There were no significant differences in clinical variables among the three groups. At week 24, there was a significant reduction in interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha in groups I and III. |

| 18 | Volker D et al., 2000 [34] | RCT | 50 RA patients | IG: fish oil containing 60% omega-3 FAs supplemented at 40 mg/kg body weight/d. CG: diet naturally low in omega-6 FAs Time: 15 weeks | Dietary supplementation resulted in a significant increase in plasma EPA and monocyte lipid levels and clinical improvement in IG. |

| 19 | Sarzi-Puttini P et al., 2000 [35] | RCT | I: 25 RA patients aged 49.56 (32–64) II: 25 RA patients aged 50.28 (29–70) | IG: A diet high in unsaturated fats and low in saturated fats with hypoallergenic foods CG: control diet, well balanced Time: 24 weeks | Significant reductions in Ritchie index, number of tender and swollen joints, and ESR were obtained in IG. |

| 20 | Zurier RB et al., 1996 [36] | RCT | 56 RA patients | IG: 2.8 gm/d GLA CG: placebo (sunflower oil capsules) Time: 6 months This was followed by a 6-month single-blind study during which all patients received GLA. | There was a statistically and clinically significant reduction in signs and symptoms of disease activity in RA patients in the IG group. During the second 6 months, improvements in disease activity were observed in both groups. |

| 21 | Leventhal LJ et al., 1994 [37] | RCT | RA patients | Black currant seed oil (BCSO) administered for 24 weeks | BCSO treatment reduced signs and symptoms of disease activity (p < 0.05). The overall clinical response was not better in the treatment group than in the placebo group. |

| 22 | Geusens P et al., 1994 [38] | RCT | I: 20 RA patients aged 56.2 ± 2 years II: 21 RA patients aged 57.2 ± 2 years III: 19 RA patients aged 59.2 ± 2 years | I: 6 capsules containing 1 g each of olive oil (placebo), II: 3 capsules each containing 1 g fish oil (1.3 g/d omega-3 FAs) plus 3 placebo capsules, III: 6 capsules containing 1 g each of fish oil (2.6 g/d omega-3 FAs) Time: 12 months | Patients taking 2.6 g/d of omega-3 FAs had significant improvements in patient global assessment, pain, and reduction in antirheumatic medication. |

| 23 | Lau CS et al., 1993 [39] | RCT | 64 RA patients | I: 10 capsules of Maxepa (171 mg EPA+ 114 mg DHA) II: placebo Duration: 12 months, then 3 months placebo. | Patients taking Maxepa consumed significantly less NSAIDs compared with placebo from month 3 [71.1 (55.9–86.2)% and 89.7 (73.7–105.7)%]. This effect reached a maximum at month 12 and persisted until month 15. No change in clinical or laboratory parameters of RA activity was observed in association with reduced NSAID consumption. |

| 24 | Leventhal LJ et al., 1993 [40] | RCT | IG: 19 RA patients aged 58 ± 13 CG: 18 RA patients aged 50 ± 16 | IG: 1.4 g/d GLA in borage seed oil CG: cottonseed oils (placebo). | Signs and symptoms of disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis decreased significantly in the IG group (p < 0.05). The overall clinical response (significant change in four measurements) was also better in the treatment group (p < 0.05). |

| 25 | Kjeldsen-Kragh J et al., 1992 [41] | RCT | 67 RA patients | I: corn oil (placebo), 7 g/day for 16 weeks, and naproxen, 750 mg/day for 10 weeks, followed by a gradual dose reduction to 0 mg/day over the next 3 weeks; II: 3.8 g EPA + 2.0 g DHA and naproxen, 750 mg/day for 16 weeks III: 3.8 g EPA + 2.0 g DHA and naproxen 750 mg/day for 10 weeks | Group II showed improvement in the duration of morning stiffness and global health score. In group III, for the duration of morning stiffness, the deterioration was significantly less compared to group I. |

| 26 | Espersen GT et al., 1992 [42] | RCT | 32 RA patients | I: dietary supplementation with omega-3 FAs (3.6 g/d) II: placebo Time: 12 weeks | Plasma Interleukin-1 beta levels were significantly reduced in the study group after 12 weeks (p < 0.03). The clinical status of the patients improved in the group receiving fish oil (p < 0.02). It was concluded that dietary supplementation with n-3 fatty acids leads to a significant reduction in plasma IL-1 beta levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. |

| 27 | Nielsen GL et al., 1992 [43] | RCT | 57 RA patients aged 61 (33–78) years IG: 29 patients CG: 28 patients | IG: 6 capsules of omega-3 FAs (3.6 g) CG: 6 capsules with a fat composition like the average Danish diet. | Significant improvement in morning stiffness and joint tenderness in the study group. |

| 28 | Brzeski M et al., 1991 [44] | RCT | 40 RA patients with upper gastrointestinal lesions due to use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs I: 19 RA patients II: 21 RA patients | I: 540 mg/d GLA (evening primrose oil 6 g/d), II: placebo (olive oil 6 g/d). | Three Patients in each group reduced their NSAID dose. The GLA treatment group had a significant reduction in morning stiffness after 3 months of supplementation, and the placebo group had a reduction in pain and joint index after 6 months. |

| 29 | van der Tempel H et al., 1990 [45] | RCT | 16 RA patients in mean age 53 years | IG: fish oil CG: placebo (fractionated coconut oil) Duration: 12 weeks | Joint swelling index and duration of morning stiffness were lower in IG than in CG. The relative amounts of EPA and DHA in plasma cholesterol ester and neutrophil membrane phospholipid fractions increased in the IG group, mainly at the expense of omega-6 Fas, and the mean in vitro production of leukotriene B4 by neutrophils decreased after 12 weeks of supplementation. Production of leukotriene B5 increased to significant amounts during fish oil treatment. |

| 30 | Kremer JM et al., 1990 [46] | RCT | 49 RA patients I: 20 RA patients aged 59 (32–81) II: 17 RA patients aged 58 (30–80 III: 12 RA patients aged 58 (22–81) | I: dietary supplement with omega-3 FA-s (27 mg/kg EPA and 18 mg/kg DHA) daily II: 54 mg/kg EPA and 36 mg/kg DHA daily III: olive oil capsules containing 6.8 gm of oleic acid daily. Time: 24 weeks | Significant improvement from baseline in the number of tender and swollen joints was observed in groups I and II. A total of 5 of 45 clinical measurements were significantly changed from baseline in group III, 8 of 45 in group I, and 21 of 45 in group II during the study. Leukotriene B4 production by neutrophils decreased by 19% in group I and 20% in group II, whereas interleukin-1 production by macrophages decreased significantly by 40.6% in group I (p = 0.06) and 54.7% in group II (p = 0.0005). |

| 31 | Tulleken JE et al., 1990 [47] | RCT | I: 14 RA patients aged 52 (29–66) years II: 14 RA patients aged 58 (43–68) years | I: fish oil II: coconut oil enriched with alpha-tocopherol (placebo) Time: 3 months | The results of the study provide evidence that the beneficial effects of fish oil supplementation cannot be attributed to the antioxidant properties of alpha-tocopherol per se. |

| 32 | Magaro M et al., 1988 [48] | RCT | I: 6 RA female patients aged 37 (20–55) years II: 6 RA female patients 36 (20–50) years | I: diet high in PUFA supplemented with EPA and DHA II: diet high in saturated fatty acids. | Fish oil consumption resulted in subjective relief of symptoms of active rheumatoid arthritis and decreased neutrophil chemiluminescence. |

| 33 | Kremer JM et al., 1985 [49] | RCT | IG: 17 RA patients in mean age 55.2 years CG: 20 RA patients in mean age 56.5 years | IG: diet high in polyunsaturated fat and low in saturated fat, with daily supplementation (1.8 g) of EPA. CG: diet with lower ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fats and placebo supplementation. Time: 12 weeks | At week 12 of the study, a reduction in morning stiffness time and number of tender joints was observed in the IG group. After discontinuation of the diet, there was a significant deterioration in the experimental group’s global assessment of disease activity, pain score, and number of tender joints. |

| 34 | Leeb BF et al., 2006 [50] | Clinical Trial | 34 RA patients aged 61 ± 4.2 years | 2 mL/kg (0.1 to 0.2 g fish oil/kg) of fish oil emulsion intravenously for 7 consecutive days Time: 5 weeks | 56% achieved a DAS28 reduction > 0.6 in V2 (mean 1.52); 27% > 1.2. In V3, 41% of patients showed a DAS28 reduction > 0.6 (mean 1.06) and 36% > 1.2. |

| 35 | Cleland LG et al., 2006 [51] | Clinical Trial | I: 13 RA patients aged 51.1 ± 15.9 II: 18 RA patients 61.8 ± 9.9 | I: no fish oil II: fish oil to provide 4–4.5 g EPA plus DHA daily or equivalent fish oil capsule dose (7 × 1 g capsules twice daily). Time: 3 years | After 3 years, AA was 30% lower in platelets and 40% lower in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in those taking fish oil. Serum thromboxane B2 was 35% lower and PGE2 in whole blood stimulated by lipopolysaccharide was 41% lower with fish oil consumption compared with no fish oil. NSAID use was reduced by 75% from baseline with fish oil intake (p < 0.05) and by 37% without fish oil (NS). Remission at 3 years was more common with fish oil use (72%) compared to no fish oil (31%). |

| 36 | Adam O et al., 2003 [52] | Clinical Trial | 68 RA patients CG: west diet (n = 34) IG: anti-inflammatory diet with a daily intake of AA < 90 mg/d (n = 34) | CG: placebo IG: fish oil capsules (30 mg/kg body weight) Time: 3 months, followed by a 2-month break between treatments. | Among patients on anti-inflammatory diets, the number of tender and swollen joints decreased by 14% during placebo treatment, whereas during fish oil capsules, there were significant reductions in the number of tender (28% vs. 11%) and swollen (34% vs. 22%) joints (p < 0.01) and greater EPA enrichment in erythrocyte lipids (244% vs. 217%) and less formation of leukotriene B(4) (34% vs. 8%, p > 0.01), 11-dehydro-thromboxane B(2) (15% vs. 10%, p < 0.05), and prostaglandin metabolites (21% vs. 16%, p < 0.003). A low-AA diet alleviates clinical signs of inflammation in RA patients and potentiates the beneficial effect of fish oil supplementation. |

| 37 | Kremer JM et al., 1995 [53] | Clinical Trial | IG: 23 RA patients in mean age 58 years CG: 26 RA patients in mean age 57 years | IG: 130 mg/kg/d omega-3 FAs CG: 9 capsules/d of corn oil Diclofenac placebo was replaced at week 18 or 22, and fish oil supplementation continued for 8 weeks (until week 26 or 30). | In the group taking fish oil, there was a significant reduction in the number of tender joints duration of morning stiffness, global arthritis activity and pain. In patients taking corn oil, none of the clinical parameters improved from baseline. The reduction in the number of tender joints remained significant 8 weeks after discontinuation of diclofenac in patients taking fish oil. IL-1 beta decreased significantly from baseline through weeks 18 and 22 in patients consuming fish oil (−7.7 +/−3.1; p = 0.026). |

| 38 | Haugen MA et al., 1994 [54] | Clinical Trial | IG: 27 RA patients in mean age 51 years CG: 26 RA patients aged 55 years | IG: 7–10 days of fasting, then a gluten-free vegan diet. For another 3–5 months. After 3.5 months a lacto-vegetarian diet. CG: continuation of normal diet. | Concentrations of 20: 3n-6 and 20: 4n-6 fatty acids were significantly reduced after 3.5 months on a vegan diet (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.01, respectively), but concentrations increased to baseline values on a lactovegetarian diet. The 20: 5n-3 concentration was significantly reduced after the vegan (p < 0.0001) and lactovegetarian (p < 0.01) diets. No correlation between changes in fatty acid profiles and clinical improvement. |

| 39 | Pullman-Mooar S et al., 1990 [55] | Clinical Trial | 7 RA patients in age range of 26–45 years and 7 normal controls | Borage seed oil (9 capsules/d = 1.1 gm/d GLA) Time: 12 weeks | GLA administration increased DGLA ratio, DGLA to AA ratio and DGLA to stearic acid ratio in circulating mononuclear cells. After 12 weeks of GLA supplementation, a significant reduction in the production of PGE2, leukotriene B4 and leukotriene C4 by stimulated monocytes was observed. |

| 40 | Jäntti J et al., 1989 [56] | Clinical Trial | I: 10 RA patients in mean age 50 years II: 10 RA patients in mean age 38 years | I: 20 mL evening primrose oil with 9% GLA II: olive oil Time: 12 weeks | Group I showed a decrease in serum levels of oleic acid, EPA, and apolipoprotein B and an increase in serum levels of linoleic acid, GLA, dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid, and AA. Serum EPA concentrations decreased in group II. The decrease in serum EPA and increase in serum AA levels induced by evening primrose oil may not be beneficial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in light of the role of these FAs as eicosanoid precursors. |

| 41 | Cleland LG et al., 1988 [57] | Clinical Trial | RA patients | I: dietary supplementation with fish oil (18 g/d) II: olive oil supplementation Time: 12 weeks | After 12 weeks, the fish oil-treated group showed improvements in tender joint scores and grip strength, a reduction in the mean duration of morning stiffness, a reduction in pain, and a 30% reduction in leukotriene B4 production by isolated neutrophils stimulated in vitro. |

| 42 | Belch JJF et al., 1988 [58] | Clinical Trial | I: 16 RA patients aged 48 (30–74) years II: 15 RA patients aged 46 (35–68) years III: 18 RA patients aged 53 (28–73) years | I: 540 mg GLA/day (EPO) II: 240 mg EPA and 450 mg GLA/day (EPO/fish oil), III: oil (placebo). After a 12-month treatment period, a 3-month placebo period was used in all groups. | After 12 months, there was a significant improvement and reduction in NSAID use in the EPO and EPO with fish oil groups. After 3 months of placebo, relapse occurred in those receiving active treatment. |

| 43 | Kremer JM et al., 1987 [59] | Clinical Trial | IG: 21 RA patients CG: 19 RA patients | IG: 2.7 g EPA + 1.8 g DHA in 15 MAX-EPA capsules (R.P. Scherer, Clearwater, FL, USA) CG: placebo capsules Timing: 14-week treatment periods and 4-week washout periods. | In the IG group, the mean time to onset of fatigue improved by 156 min and the number of tender joints decreased by 3.5. Production of leukotriene B4 by neutrophils was correlated with a decrease in the number of tender joints (r = 0.53; p < 0.05). |

| 44 | Beyer K et al., 2021 [60] | Observational study | 78 RA patients aged 57.0 ± 12.0 years with varying degrees of periodontitis | No | Elevated phospholipid levels with concomitant decreased choline levels, increased medium-chain acylcarnitines (MC-AC), and decreased MC-AC to long-chain (LC)-AC ratio were associated with prednisolone intake. Higher concentrations of total FA and total cholesterol were found in active RA. |

| 45 | Mustonem AM et al., 2019 [61] | Observational study | I: 10 RA patients after total knee replacement II: 10 OA patients after total knee replacement III: 6 atroscopy patients not suffering from RA or OA | No | After treatment, the proportion of omega-6 FAs significantly decreased in the OA and RA groups. The proportion of MUFAs increased in both RA and OA patients. RA patients had a lower proportion of 20: 4n-6, total omega-6 and 22: 6n-3, and a lower omega-3 product/precursor ratio compared with OA patients. Mean FA chain length in synovial fluid decreased in both diagnoses. |

| 46 | Nasriati F et al., 2018 [62] | Observational study | 35 RA patients with an average age of 45.29 years | No | There was no significant correlation between TNF-α levels and VCAM-1 levels (p = 0.677; r = +0.073) or between TNF-α levels and FFA levels (p = 0.227; r = −0.21). There was a weak negative correlation of FFA with sVCAM-1. |

| 47 | de Pablo P et al., 2018 [63] | Observational study | I: 96 pre-RA subjects II: 258 matched controls | No | The erythrocytic level of omega-6 FA was inversely associated with RA risk, whereas no association was observed with other omega-6 or omega-3 FAs. |

| 48 | Beyer K et al., 2018 [64] | Observational study | 78 RA patients aged 57 ± 12 | No | Patients with omega-3 > 8 index had lower VAS pain severity score and lower periodontal probing depth. |

| 49 | Bärebring L et al., 2018 [65] | Observational study | 66 RA patients aged 59.9 ± 12.2 | No | An omega-3 rich diet with animal fat restriction was not associated with DAS28 (B = −0.02, p = 0.787), but high diet quality was significantly negatively associated with hs-CRP (B = −0.6, p = 0.044) and ESR (B = −2.4, p = 0.002). |

| 50 | Gan RW et al., 2017 [66] | Observational study | 136 RA patients: I. Anti-CCP2(+) (n = 40, aged 43.7 ± 15.4) II. High titre RF(+) (n = 27, aged 48.1 ± 13.2) III. RF(−) and anti-CCP2(−) (n = 69, aged 46.5 ± 13.9 ) | No | Increased omega-3 FA% in RBCs was inversely associated with RF in SE-positive participants and anti-CCP positivity in SE-positive participants, but not in SE-negative participants. In the SERA cohort, use of omega-3 FA supplements was associated with a lower incidence of RF. |

| 51 | Jeffery L et al., 2017 [67] | Observational study | 22 RA patients aged 53.0 ± 12.5 | No | Higher plasma EPA concentrations were associated with greater reduction in DAS28. Plasma EPA PC was positively associated with response to treatment according to EULAR criteria. An increase in Th17 cells after therapy was associated with a lack of response to anti-TNF. ETN increased Th17 frequency in vitro. EPA status was associated with clinical improvement on anti-TNF therapy in vivo and prevented the effects of ETN on Th17 cells in vitro. |

| 52 | Gan RW et al., 2016 [68] | Observational study | I: Anti-CCP2 (+) (n = 30, aged 45.6 ± 16.5 ) II: Control (Ab−) (n = 47, aged 48.6 ± 14.4) | No | The probability of anti-CCP2 was inversely proportional to the total FA omega-3 content in RBCs (0.47; 95% CI 0.24–0.92). |

| 53 | Rodríguez-Carrio J et al., 2016 [69] | Observational study | 124 RA patients aged 52.47 ± 12.76 | No | RA patients showed reduced levels of palmitic (p < 0.0001), palmitoleic (p = 0.002), oleic (p = 0.010), arachidonic (p = 0.027), EPA (p < 0.0001) and DHA (p < 0.0001) acids and an overrepresentation of the NEFA profile compared to HC (p = 0.002). FA imbalance may underlie IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells. Changes in NEFA levels were associated with clinical response to TNF-α blockade. |

| 54 | Kosinska MK et al., 2015 [70] | Observational study | I: 16 post-mortem donors II: 20 RA patients aged 56 (49–72) III: 26 eOA patients aged 38 (26–56) IV: 22 lOA patients aged 69 (53–74) | No | Significant changes were noted between groups in the relative distribution of PLs and the degree of FA saturation and chain length of FAs. Compared with the control group, more FA-saturated LPC species were reported in the synovial fluid of eOA (63.5% (59.0–70.7%)), lOA (68.8% (65.3–70.6%)) and RA (72.4% (70.2–75.4%)) patients. |

| 55 | Di Giuseppe D et al., 2014 [71] | Observational study | 32,232 women in whom 205 cases of RA were diagnosed during a 7.5-year follow-up | No | Consumption of omega-3 FAs greater than 0.21 g/day was associated with a 35% reduced risk of developing RA (RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.48–0.90), and consumption of >0.21 g/day was associated with a 52% reduced risk of developing RA. Long-term consumption of ≥1 serving of fish per week compared with <1 serving was associated with a 29% reduced risk (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.48–1.04). |

| 56 | Lee AL. & Park Y, 2013 [72] | Observational study | CG: 100 healthy women aged 50.04 ± 8.00 IG: 100 RA female patients aged 48.39 ± 9.69 | no | In RA patients, the levels of ALA, EPA and omega-3 index [EPA + DHA] in erythrocytes were significantly lower than those in the CG. Regression analysis showed that ALA, EPA levels and EPA to AA ratio were negatively associated with RA risk. PGE2 concentration was significantly decreased with increased DHA concentration in erythrocytes of RA patients. |

| 57 | Hayashi H et al., 2012 [73] | Observational study | 37 RA patients aged 65 ± 9.8 years I: Low disease activity, DAS28 < 3.2 (n = 18) II: High disease activity, DAS28 ≥ 3.2 (n = 19) | no | Serum leptin and albumin levels were significantly lower, while inflammatory markers were elevated, in the high disease activity group. Dietary assessment showed lower fish oil intake and lower MUFA intake ratio in the high disease activity group. There was a negative correlation between DAS28 and dietary intake in terms of MUFA/FAs intake ratio. Serum oxidative stress marker (reactive oxygen metabolites) showed a positive correlation with DAS28. |

| 58 | Ormseth MJ et al., 2011 [74] | Observational study | 166 RA patients aged 54.0 (45.0–62.8) and 92 control subjects aged 53.0 (44.8–59.2) | no | Serum FFAs levels were not significantly different in RA patients and controls (0.56 mmol/L (0.38–0.75) and 0.56 mmol/L (0.45–0.70), respectively, p = 0.75). In multivariate regression analysis, serum FFAs levels were associated with HOMA-IR (p = 0.011), CRP (p = 0.01), triglycerides (p = 0.005) and Framingham risk score (p = 0.048) in RA but not with IL-6 (p = 0.48). |

| 59 | Elkan AC et al., 2009 [75] | Observational study | 80 RA patients in mean age 61.4 ± 12 years | no | A total of 18% of women and 26% of men suffered from rheumatoid cachexia. These patients reported high dietary saturated fat intake, which partially correlated with fatty acid composition in adipose tissue and significantly with disease activity. However, patients with and without cachexia did not differ in their dietary fat intake or in their adherence to the Mediterranean diet. |

| 60 | Rosell M et al., 2009 [76] | Observational study | I: 1889 RA patients II: 2145 controls | no | Fatty fish consumption was associated with a moderately reduced risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (OR 0.8 (95% confidence interval = 0.6–1.0)). |

| 61 | Das Gupta AB et al., 2009 [77] | Observational study | I: 50 patients aged 49.9 ± 8.2 years II: 50 patients aged 44.7 ± 7.7 years | I: indomethacin (75 mg/d) II: indomethacin (75 mg/d) and omega-3 FAs (3 g/d) over 12 weeks. | Both groups showed moderate improvement in disease activity after 12 weeks of treatment. Physical functioning, physical role, body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, grip strength and duration of morning stiffness improved significantly better in the combination group compared with the indomethacin-only treatment group. |

| 62 | Pedersen M et al., 2005 [78] | Observational study | 57,053 individuals from the Danish National Registry. Sixty-nine individuals developed RA. | no | Increased intake of 30 g/d of fatty fish (≥8 g fat/100 g fish) was associated with a 49% reduction in RA risk (p = 0.06), whereas intake of medium-fat fish (3–7 g fat/100 g fish) was associated with a significantly increased RA risk. |

| 63 | Gruenwald J et al., 2004 [79] | Observational study | 50 RA patients aged between 29 and 73 years | Take 1 capsule of Sanhelios Mussel Lyprinol Lipid Complex (458 mg of fish oil concentrate (50% EPA; 50% DHA) and 35 mg of Lyprinol) twice daily (morning and evening), then from day 3, 2 capsules twice daily. Duration: 12 weeks | A reduction in morning stiffness time, painful and swollen joints was observed at 6 and 12 weeks post-study. Pain was reduced by an average of 60%. |

| 64 | Furse RK et al., 2001 [80] | Observational study | healthy volunteers and patients with RA | no | Administration of GLA, an unsaturated fatty acid, reduces joint inflammation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting IL-1 beta release from LPS-stimulated human monocytes. GLA induces a protein that reduces the stability of pro-IL-1 beta mRNA. IL-1 beta is important for host defence, but the enhancement mechanism may be excessive in genetically predisposed patients. Reduction of IL-1 beta autoinduction may therefore be protective in some patients with endotoxic shock and diseases characterised by chronic inflammation. |

| 65 | Linos A et al., 1999 [81] | Observational study | 145 RA patients and 188 control subjects | no | In multiple regression analysis, consumption of olive oil or cooked vegetables significantly reduced the risk of developing RA (OR: 0.38 and 0.24, respectively). |

| 66 | Fraser DA et al., 1999 [82] | Observational study | 9 RA patients after completion of 7-day fasting aged 51 (31–65) years | no | Both the concentration of the FFA mixture and the ratio of unsaturated and saturated fatty acids significantly affected lymphocyte proliferation in vitro (p < 0.0001). |

| 67 | Shapiro JA et al., 1996 [83] | Observational study | 324 RA female patients and 1245 controls aged 15–64. | no | Consumption of cooked or baked fish but was associated with a reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for 1- < 2 servings and > or =2 servings of cooked or baked fish per week, compared with <1 serving, were 0.78 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.53–1.14) and 0.57 (95% CI = 0.35–0.93). |

| 68 | Magarò M et al., 1992 [84] | Observational study | 20 female RA patients aged between 25 and 45 years | IG: A diet enriched with fish oil (EPA and DHA) CG: current diet | Patients with IG had a significantly lower erythrocyte sedimentation rate and were observed to have improved clinical parameters compared to CG. |

| 69 | Jacobsson L et al., 1990 [85] | Observational study | IG1: 21 patients with recently diagnosed RA aged 57 (25–78) years IG2: 21 patients with RA of longer duration (mean 15 years, range 3–43) CG: 32 men and 25 women aged 57 years (range 50–70 years) and had no rheumatic symptoms at the time of the study. | no | The proportion of 18:2 serum phosphatidylcholine correlated inversely with such acute phase proteins as orosomucoid and CRP. It is proposed that decreases in essential FAs are associated with increased desaturase/elongation enzyme activity, increased eicosanoid production, or metabolic changes secondary to a cytokine-mediated inflammatory response. However, ascorbic acid levels were lower in RA and correlated inversely with haptoglobin, orosomucoid, and CRP levels, indicating an association between ascorbic acid levels and degree of inflammation. |

| 70 | Sperling RI et al., 1987 [86] | Observational study | 12 RA patients | 20 g/d of Max-EPA fish oil for 6 weeks | After fish oil supplementation, the AA:EPA ratio in neutrophil cell lipids decreased from 81:1 to 2.7:1, and mean leukotriene B4 production decreased by 33%. There was also a 37% decrease in platelet-activating factor production at week 6. Fish oil supplementation may have anti-inflammatory effects. |

| 71 | Klickstein LB et al., 1980 [87] | Observational study | Synovial fluid and synovial tissue sonication of patients with RA, SA and NIA | no | The concentration of 5(S),12(R)-dihydroxy-6,8,10-(trans/trans/cis)-14-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid (leukotriene B4) in synovial fluid was significantly elevated in patients with RA and rheumatoid factor present (p < 0.05, n = 14) and in patients with SA (p < 0.05, n = 10), compared with those with NIA (n = 9). The content of 5(S)-hydroxy-6,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE), but not leukotriene B4, was significantly elevated in the synovial tissue of seven RA patients compared with four NIA subjects (p < 0.05). A single intra-articular corticosteroid injection significantly decreased leukotriene B4 levels in synovial fluid of six RA patients. These data suggest the involvement of the potent chemotactic factors 5-HETE and leukotriene B4 in human inflammatory disease. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tański, W.; Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.; Tabin, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. The Relationship between Fatty Acids and the Development, Course and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051030

Tański W, Świątoniowska-Lonc N, Tabin M, Jankowska-Polańska B. The Relationship between Fatty Acids and the Development, Course and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(5):1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051030

Chicago/Turabian StyleTański, Wojciech, Natalia Świątoniowska-Lonc, Mateusz Tabin, and Beata Jankowska-Polańska. 2022. "The Relationship between Fatty Acids and the Development, Course and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis" Nutrients 14, no. 5: 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051030

APA StyleTański, W., Świątoniowska-Lonc, N., Tabin, M., & Jankowska-Polańska, B. (2022). The Relationship between Fatty Acids and the Development, Course and Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrients, 14(5), 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051030