Use of Nutritional Supplements Based on L-Theanine and Vitamin B6 in Children with Tourette Syndrome, with Anxiety Disorders: A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Clinical Assessment

2.4. Measures

2.5. Psychoeducation

2.6. Composition of the Nutritional Supplements

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

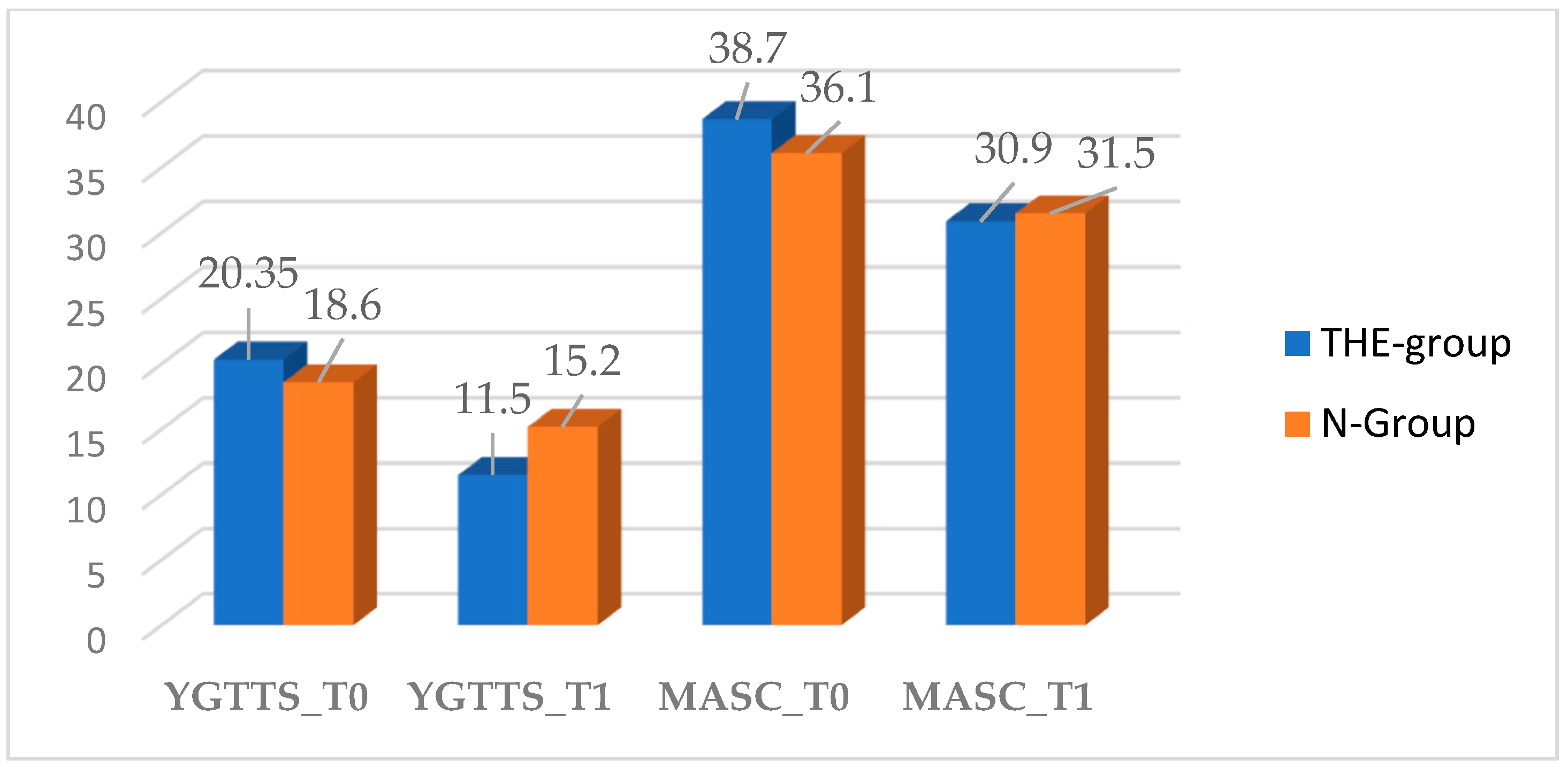

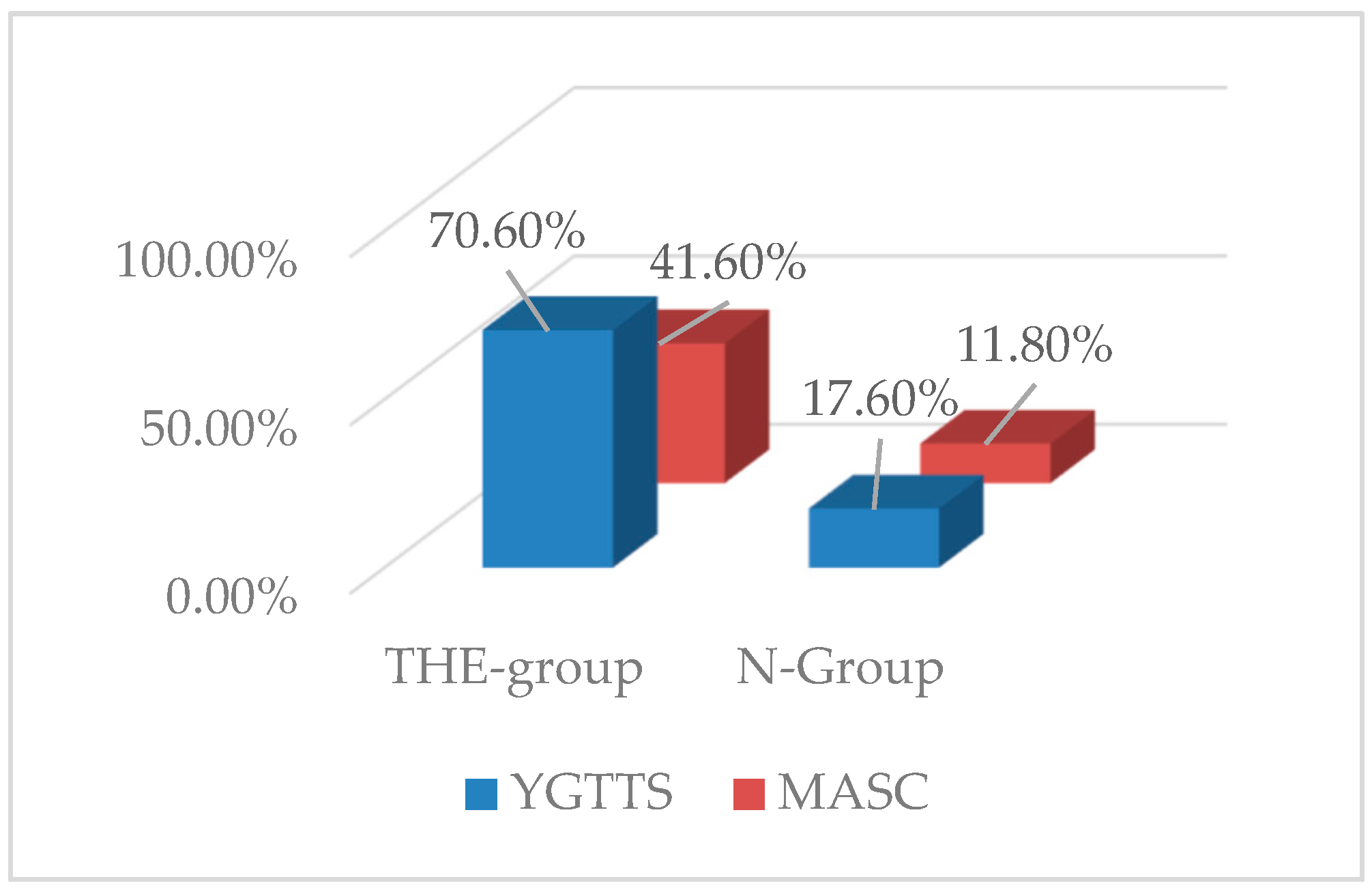

3.2. YGTTS Outcome

3.3. MASC Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American-Psychiatric-Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, R.; Gulisano, M.; Pellico, A.; Calì, P.V.; Curatolo, P. Tourette Syndrome and Comorbid Conditions. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, M.M. A personal 35 year perspective on Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: Prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidities, and coexistent psychopathologies. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.; Gulisano, M.; Calì, P.V.; Curatolo, P. Tourette Syndrome and comorbid ADHD: Current pharmacological treatment options. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2013, 17, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, M.M.; Eapen, V.; Singer, H.S.; Martino, D.; Scharf, J.M.; Paschou, P.; Roessner, V.; Woods, D.W.; Hariz, M.; Mathews, C.A.; et al. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 16097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, J.S. Tourette’s syndrome and its borderland. Pract. Neurol. 2018, 18, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschtritt, M.E.; Lee, P.C.; Pauls, D.L.; Dion, Y.; Grados, M.; Illmann, C.; King, R.A.; Sandor, P.; McMahon, W.M.; Lyon, G.J.; et al. Lifetime Prevalence, Age of Risk, and Genetic Relationships of Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders in Tourette Syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cravedi, E.; Deniau, E.; Giannitelli, M.; Xavier, J.; Hartmann, A.; Cohen, D. Tourette syndrome and other neurodevelopmental disorders: A comprehensive review. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2017, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gulisano, M.; Barone, R.; Mosa, M.; Milana, M.; Saia, F.; Scerbo, M.; Rizzo, R. Incidence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Youths Affected by Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome Based on Data from a Large Single Italian Clinical Cohort. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwitz, L.; Pringsheim, T. Cinical utility of screening for anxiety and depression in children with Tourette syndrome. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Roessner, V.; Eichele, H.; Stern, J.S.; Skov, L.; Rizzo, R.; Debes, N.M.; Nagy, P.; Cavanna, A.E.; Termine, C.; Ganos, C.; et al. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders—version 2.0. Part III: Pharmacological treatment. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behler, N.; Leitner, B.; Mezger, E.; Weidinger, E.; Musil, R.; Blum, B.; Kirsch, B.; Wulf, L.; Löhrs, L.; Winter, C.; et al. Cathodal tDCS Over Motor Cortex Does Not Improve Tourette Syndrome: Lessons Learned From a Case Series. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, R.; Pellico, A.; Silvestri, P.R.; Chiarotti, F.; Cardona, F. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Behavioral, Educational, and Pharmacological Treatments in Youths with Chronic Tic Disorder or Tourette Syndrome. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, R.; Gulisano, M. Treatment options for tic disorders. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 20, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fründt, O.; Woods, D.; Ganos, C. Behavioral therapy for Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2017, 7, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Lopez, R.; Perea-Milla, E.; Garcia, C.R.; Rivas-Ruiz, F.; Romero-Gonzalez, J.; Moreno, J.L.; Faus, V.; Aguas, G.D.C.; Diaz, J.C.R. New therapeutic approach to Tourette Syndrome in children based on a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind phase IV study of the effectiveness and safety of magnesium and vitamin B6. Trials 2009, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, M.; McDonald, A.C.; Xiong, L.; Crowley, D.C.; Guthrie, N. A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study to Investigate the Efficacy of a Single Dose of AlphaWave® l-Theanine on Stress in a Healthy Adult Population. Neurol. Ther. 2021, 10, 1061–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidese, S.; Ota, M.; Wakabayashi, C.; Noda, T.; Ozawa, H.; Okubo, T.; Kunugi, H. Effects of chronic l-theanine administration in patients with major depressive disorder: An open-label study. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2017, 29, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Sakamoto, F.; Metzker Pereira Ribeiro, R.; Amador Bueno, A.; Oliveira Santos, H. Psychotropic effects of L-theanine and its clinical properties: From the management of anxiety and stress to a potential use in schizophrenia. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 147, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.L.; Everett, J.M.; D’Cunha, N.M.; Sergi, D.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Keegan, R.; McKune, A.; Mellor, D.; Anstice, N.; Naumovski, N. The Effects of Green Tea Amino Acid L-Theanine Consumption on the Ability to Manage Stress and Anxiety Levels: A Systematic Review. Mater. Veg. 2020, 75, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarris, J.; Byrne, G.J.; Cribb, L.; Oliver, G.; Murphy, J.; Macdonald, P.; Nazareth, S.; Karamacoska, D.; Galea, S.; Short, A.; et al. L-theanine in the adjunctive treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 110, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyon, M.R.; Kapoor, M.P.; Juneja, L.R. The effects of L-theanine (Suntheanine®) on objective sleep quality in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alter-Nativ. Med. Rev. J. Clin. Ther. 2011, 16, 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ritsner, M.S.; Miodownik, C.; Ratner, Y.; Shleifer, T.; Mar, M.; Pintov, L.; Lerner, V. L-Theanine Relieves Positive, Activation, and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients With Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarris, J.; Byrne, G.J.; Oliver, G.; Cribb, L.; Blair-West, S.; Castle, D.; Dean, O.M.; Camfield, D.A.; Brakoulias, V.; Bousman, C.; et al. Treatment of Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder with Nutraceuticals (TRON): A 20-week, open label pilot study. CNS Spectr. 2021, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Lopez, R.; Romero-Gonzalez, J.; Perea-Milla, E.; Ruiz-García, C.; Rivas-Ruiz, F.; Béjar, M.D.L.M. Estudio piloto sin grupo control del tratamiento con magnesio y vitamina B6 del síndrome de Gilles de la Tourette en niños. Med. Clín. 2008, 131, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousain-Bosc, M.; Roche, M.; Polge, A.; Pradal-Prat, D.; Rapin, J.; Bali, J.P. Improvement of neurobehavioral dis-orders in children supplemented with magnesium-vitamin B6. II. Pervasive developmental disorder-autism. Magnes. Res. 2006, 19, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kałużna-Czaplińska, J.; Michalska, M.; Rynkowski, J. Vitamin supplementation reduces the level of homocysteine in the urine of autistic children. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckman, J.F.; Riddle, M.A.; Hardin, M.T.; Ort, S.I.; Swartz, K.L.; Stevenson, J.; Cohen, D.J. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial Testing of a Clinician-Rated Scale of Tic Severity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1989, 28, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, J.S.; Parker, J.D.; Sullivan, K.; Stallings, P.; Conners, C.K. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor Structure, Reliability, and Validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; The Psychological Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.; Edelbrock, C. The Child Behavior Checklist Manual; The University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, M.; Beck, A.T. An empirical-clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. In Depression in Childhood: Diagnosis, Treatment and Conceptual Models; Schulterbrandt, J.G., Raskin, A., Eds.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill, L.; Riddle, M.A.; McSwiggin-Hardin, M.; Ort, S.I.; King, R.A.; Goodman, W.K.; Cicchetti, D.; Leckman, J.F. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and Validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, A.B.; Wu, M.S.; McGuire, J.F.; Storch, E.A. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 37, 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermilion, J.; Pedraza, C.; Augustine, E.F.; Adams, H.R.; Vierhile, A.; Lewin, A.B.; Collins, A.T.; McDermott, M.P.; O’Connor, T.; Kurlan, R.; et al. Anxiety Symptoms Differ in Youth With and Without Tic Disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantel, B.J.; Meyers, A.; Tran, Q.Y.; Rogers, S.; Jacobson, J.S. Nutritional Supplements and Complementary/Alternative Medicine in Tourette Syndrome. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 14, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.L.; Ludlow, A.K. Patterns of Nutritional Supplement Use in Children with Tourette Syndrome. J. Diet. Suppl. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałużna-Czaplińska, J.; Socha, E.; Rynkowski, J. B vitamin supplementation reduces excretion of urinary dicarboxylic acids in autistic children. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, L.; Dye, L.; De Fer, B.B.; Mazur, A.; Pickering, G.; Pouteau, E. Effect of magnesium and vitamin B6 supplementation on mental health and quality of life in stressed healthy adults: Post-hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Stress Health 2021, 37, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouteau, E.; Kabir-Ahmadi, M.; Noah, L.; Mazur, A.; Dye, L.; Hellhammer, J.; Pickering, G.; Dubray, C. Superiority of magnesium and vitamin B6 over magnesium alone on severe stress in healthy adults with low magnesemia: A randomized, single-blind clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hannant, P.; Cassidy, S.; Renshaw, D.; Joyce, A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised-designed GABA tea study in children diagnosed with autism spectrum conditions: A feasibility study clinical trial registration: ISRCTN 72571312. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidese, S.; Ogawa, S.; Ota, M.; Ishida, I.; Yasukawa, Z.; Ozeki, M.; Kunugi, H. Effects of L-Theanine Administration on Stress-Related Symptoms and Cognitive Functions in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ludlow, A.K.; Rogers, S. Understanding the impact of diet and nutrition on symptoms of Tourette syndrome: A scoping review. J. Child Health Care 2018, 22, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Partecipant Characteristics | Total Sample (n = 34) | THE-Group (n = 17) | N-Group (n = 17) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 30 (88.2%) | 15 (88.2%) | 15 (88.2%) | 1 |

| Mean age (years) ± SD | 10.4 (±3.5) | 9.3 (±3.9) | 11.5 (±2.7) | 0.6078 |

| Tic disorders | 4 (11.8%) | 3 (17.6%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0.157 |

| TS | 30 (88.2%) | 14 (82.4%) | 16 (94.1%) | 0.287 |

| Measures | Total Sample (n = 34) | THE-Group (n = 17) | N-Group (n = 17) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIQ | 97.5 (±9.9) | 99.7 (±12.1) | 96.5 (±7.6) | 0.3627 |

| YBOCS | 3.8 (±5.9) | 3.2 (±5.7) | 4.5 (±6.2) | 0.5290 |

| CDI | 2.9 (±4.5) | 2.9 (±4.96) | 2.9 (±4.1) | 1 |

| YGTSS | 19.5 (±5.6) | 20.35 (±5.8) | 18.6 (±5.4) | 0.3694 |

| MASC | 37.4 (±8.5) | 38.7 (±8.8) | 36.1 (±8.35) | 0.3835 |

| THE-Group (n = 17) |

N-N-Group (n = 17) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| YGTSS | 0.0460 | ||

| 11.5 (±6.1) | 15.2 (±4.1) | |

| 8.85 (43.5%) | 3.4 (18.3%) | |

| MASC | 0.8457 | ||

| 30.9 (±9.4) | 31.5 (±8.4) | |

| 7.8 (20.2%) | 4.6 (12.7%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizzo, R.; Prato, A.; Scerbo, M.; Saia, F.; Barone, R.; Curatolo, P. Use of Nutritional Supplements Based on L-Theanine and Vitamin B6 in Children with Tourette Syndrome, with Anxiety Disorders: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040852

Rizzo R, Prato A, Scerbo M, Saia F, Barone R, Curatolo P. Use of Nutritional Supplements Based on L-Theanine and Vitamin B6 in Children with Tourette Syndrome, with Anxiety Disorders: A Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2022; 14(4):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040852

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizzo, Renata, Adriana Prato, Miriam Scerbo, Federica Saia, Rita Barone, and Paolo Curatolo. 2022. "Use of Nutritional Supplements Based on L-Theanine and Vitamin B6 in Children with Tourette Syndrome, with Anxiety Disorders: A Pilot Study" Nutrients 14, no. 4: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040852

APA StyleRizzo, R., Prato, A., Scerbo, M., Saia, F., Barone, R., & Curatolo, P. (2022). Use of Nutritional Supplements Based on L-Theanine and Vitamin B6 in Children with Tourette Syndrome, with Anxiety Disorders: A Pilot Study. Nutrients, 14(4), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040852