Abstract

Plant-based diets are seen as a food-based strategy to address both the impact of dietary patterns on the environment, to reduce climate change impact, and also to reduce rates of diet-related disease. This study investigated self-reported consumer purchasing behaviour of plant-based alternative foods (PBAF) and wholefood plant protein foods (legumes) with a cross-sectional online survey. We identified the sociodemographic factors associated with purchasing behaviour and examined knowledge about protein and plant-based diets. We recruited and obtained consent from n = 1177 adults aged >18 from England and Scotland (mean age (± standard deviation (SD)) 44 (16.4) years), across different areas of social deprivation, based on postcode. Descriptive statistics were conducted, and sociodemographic factors were examined by computing covariate-adjusted models with binary logistic regression analysis. A total of 47.4% (n = 561) consumers purchased PBAF and 88.2% (n = 1038) wholefood plant-proteins. The most frequently purchased PBAF were plant-based burgers, sausages, and mince/meatballs. Individuals from low deprivation areas were significantly more likely than individuals from high deprivation areas to purchase wholefood plant-proteins (odds ratio (OR) 3.46, p = 0.001). People from low deprivation areas were also more likely to recognise lentils as good source of protein (OR 1.94, p = 0.003) and more likely to recognise plant-based diets as healthy (OR 1.79, p = 0.004) than those from high deprived areas. These results support current trends of increasing popularity of PBAF, which is positive for the environment, but also highlights these products as being ultra-processed, which may negatively impact on health. The study also re-enforces the link between deprivation, reduced purchasing of wholefood plant-proteins and knowledge of plant-based protein and diets. Further research is needed to examine healthfulness of PBAF and how sociodemographic factors, especially deprivation, affect both food choice and consumption of wholefood plant-proteins.

1. Introduction

Global action is required to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to limit the damage of global warming. Both the climate and environment are severely endangered by our current food systems and dietary approaches, particularly in the developed world [1]. The production and consumption of meat, and other animal-derived foods and beverages, significantly contribute to GHG emissions, both in the UK and worldwide [1,2]. At the same time, societies face high rates of diet-related disease due to consumption of excess calories from foods high in energy, also salt, saturated fats and added sugar. These are often foods that are highly processed and account for 25–60% of daily energy intake in many countries [3]. In the UK, a suboptimal diet is estimated to cause a loss of 1.5 million years of healthy lives [4] and one in seven deaths, contributing to worldwide 11 million deaths related to poor dietary habits [5,6]. Affordability, accessibility and availability of unprocessed plant-based protein-rich foods remain a challenge to support healthy and environmentally sustainable diets [7]. Plant-based diets are viewed as an important food strategy by science and policy makers to tackle both health and environmental problems and achieve healthy, sustainable diets and a resilient food system [8,9]. Plant-based diets are widely seen as diets that emphasise a variety of plant foods and simultaneously attempt to reduce or even exclude animal-derived foods [10]. Plant protein sources can be wholefood plant proteins, like legumes (peas, beans, lentil or soya), wholegrains, nuts and seeds [11] or plant-based alternative foods (PBAF). PBAF are made from plant-proteins and are defined, “to mimic the taste and texture of their animal-based counterpart” [12]. Example products are meat-free burgers or sausages, QuornTM (Stokesley, UK) products or milk alternatives. This analysis specifically focuses on the purchasing of wholefood plant proteins in the form of legumes and PBAF (QuornTM, soya products, other meat-free products). QuornTM is a brand of mycoprotein meat alternatives (Stokesley, UK), referred to as mycoprotein for the remainder of the paper.

There is a scarcity of research on recent consumer behaviour relating to plant-protein choices. A recent review from Alae-Carew et al. in 2022 provides insight, by analysing the consumption of PBAF [12] in the UK, reporting females, millennials and those with higher income as having significantly higher PBAF intake. Despite many systematic reviews having explored attitudes and acceptance around the consumption of more sustainable protein-foods or reduced meat intake [13,14,15], it is often highlighted that studies neglect comparisons of a multitude of sociodemographic variables beyond gender or cultural background [15]. These factors are important to consider to ensure a healthy, safe and equitable food system for all [4,16]. This poses as an opportunity for our current research to consider other sociodemographic variables such as country of residence, gender, age, ethnic background, but also deprivation levels. Socioeconomic status (SES) or index of deprivation (IMD) have been repeatedly identified in the literature as important factors driving food choice and behaviour [17,18]. More evidence is needed regarding plant-based eating, in order to support consumers facing deprivation, to encourage a transition to both healthy and sustainable eating. Finally, it was also identified that there is a paucity of research concerning consumer knowledge about protein, its physiology and health-benefits [19]. Taking the above into consideration, more information is needed about consumer behaviour, sociodemographic predictors of purchasing behaviour, as well as consumer’s knowledge of protein. This knowledge could inform public health strategies and messages to enable transition towards purchasing and consuming more plant-based foods [7]. Therefore, this study aims to (1) contrast consumer purchasing trends of plant-based protein products in Scotland and England (2) analyse sociodemographic factors within consumer behaviour of plant-based protein purchasing, i.e., gender, age, ethnic background and IMD and (3) explore consumers’ knowledge about protein, i.e., sources, physiological role and health benefits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Sample

Data for this study originated from the cross-sectional survey, to assess UK attitudes, beliefs and trends in plant-based choices, from the study, “What Plants are on your plate” conducted in April 2022 on the Qualtrics market research platform. Data aimed to gather responses from 1000 adults (aged > 18 years), fluent in English, as n = 500 from England and Scotland. Participants were members of the Qualtrics Research Panel. This is a pre-recruited sample of panelists similar to the population of a census [20]. This ensured random participants of an adult population in England or Scotland participated in the survey. The study questionnaire is included in Supplementary Materials S1.

2.2. Sociodemographic Data

Sociodemographic information including country of residence, age, gender, IMD were collected as part of this online questionnaire. Country of residence could either be selected as Scotland or England and gender was categorised during analysis into male, female and other. IMD levels were derived from postcode data and coded into quintiles with 1 being the least deprived and 5 being the most deprived. In England and Scotland IMD levels provide a relative measure of deprivation derived from information of several aspects of deprivation, such as income, employment, education, health deprivation and disability and even barriers to housing and services, crime and living environment [21]. Age was collected as self-reported numerical data and was combined into generation groups, which were, Generation Z (age 18–23), Millennials (age 24–39), Generation X (age 40–55), Baby Boomers (age 56–74) and Traditionalists (75+ years), similar to those described by Alae-Carew et al. in adults [12].

2.3. Purchasing Data and Protein Knowledge Data

Consumer purchasing behaviour data was obtained in the survey using multiple-choice lists of wholefood plant-proteins and processed plant-based alternative food products to indicate whether these are purchased in general grocery shops. Further specification data of kind and state (e.g., canned, frozen, dried) was also chosen (see questionnaire in Supplementary Materials S1).

Categorical answers to statements regarding protein’s physiological role and health benefits were also included in this study, showing agreement, neutrality or disagreement with protein sources, environmental and health prevention benefits of protein.

2.4. Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe purchasing behaviour and characteristics (using IBM Corporation, released 2021, version 28.0, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA). Participants were categorised into two grouping factors: PBAF purchasers and wholefood protein purchasers. They were categorised as PBAF purchasers if they indicated purchasing any alternative plant-protein products (mycoprotein products, soya products, other meat free products). Similarly, participants were categorised as wholefood protein purchasers if they indicated purchasing any legume products (green beans or peas, beans or lentils). To compare these two purchasing groups, chi-square tests for trend and continuity correction were conducted.

Factors affecting the grouping (PBAF purchasers and wholefood plant-protein purchasers) were tested using binary logistic regression models to determine associations between the consumption and sociodemographic covariates. Initially, they were analysed in separate univariate models for each sociodemographic factor. Following this a multivariate analysis in one model, adjusted for country of residence, gender, age, ethnicity and IMD, was carried out. Furthermore, the number of purchased product types from each PBAF purchasing and wholefood plant-protein were scored and distributions across sociodemographic groups were analysed using non-parametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Throughout all tests, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

For the third research objective, data were described using descriptive statistics, and non-parametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were carried out to compare between different sociodemographic groups and their agreement with the protein knowledge statements. In addition, for comparability of sociodemographic covariates with both knowledge statements and purchasing behaviour, knowledge statements were computed into binary variables to carry out a further binary logistic regression with a multivariate model.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Rowett Institute Ethics Panel and the University of Aberdeen Research Governance (812). All subjects gave informed consent, in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and all researchers had in-date certificates of ethical research training. All data from the survey was completely anonymised, e.g., all postcode data was removed. The data will also be made publicly available on the Open Science Framework, which participants gave their consent to before participation.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The sample consisted of 1177 adults aged between 18 and 89 years, 57.4% of which were from England and 45.8% were from Scotland. The mean age of the population was 44.0 years (standard deviation (SD) 16.4), with 65.4% of the sample identified as female and 33.8% identified as male. A summary of the participant characteristics is shown in Table 1. Of the total population 47.4% (n = 561) were found to purchase PBAF in their food shop. In Scotland only 42.6% purchased PBAF whilst in England 57.4% did. Overall, 88.2% purchased wholefood plant proteins. 9.9% (n = 117) and 2.5% (n = 30) subjects disclosed they were vegetarian and vegan, which is above the UK average rates of vegetarianism and veganism of 2.9% and 0.4%, respectively, in 2014, for households where the respondent was born between 1930 and 1974 [22]. However a market research portal recently suggested that current rates lie within 7% (vegetarianism) and 4% (veganism) in the UK [23].

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

3.2. Purchasing Trends of Plant-Based Foods

3.2.1. Plant-Based Alternative Food Products

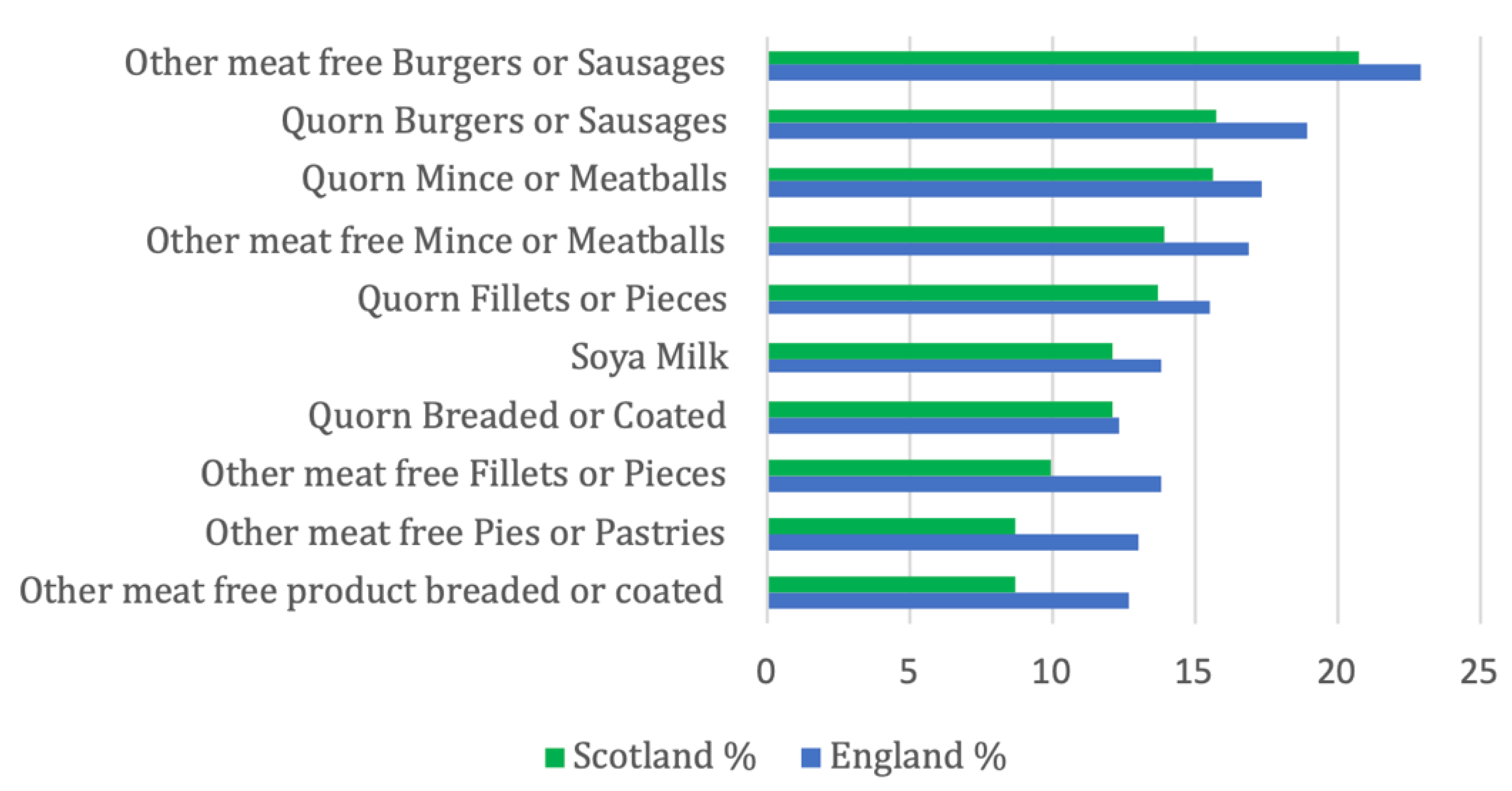

When looking at purchasing trends, we have presented the 10 most popular products (Figure 1), with the three most frequently purchased PBAFs being “other meat free burgers and sausages” “mycoprotein burgers and sausages” followed by mycoprotein mince and meatballs. They all depict meat free substitutes for ultra-processed meat products. Four products were mycoprotein products. It can be seen, that more PBAF were purchased in England than in Scotland, which was statistically significant (p = 0.041).

Figure 1.

Ten most frequently purchased plant-based alternative food items.

3.2.2. Wholefood Plant-Proteins

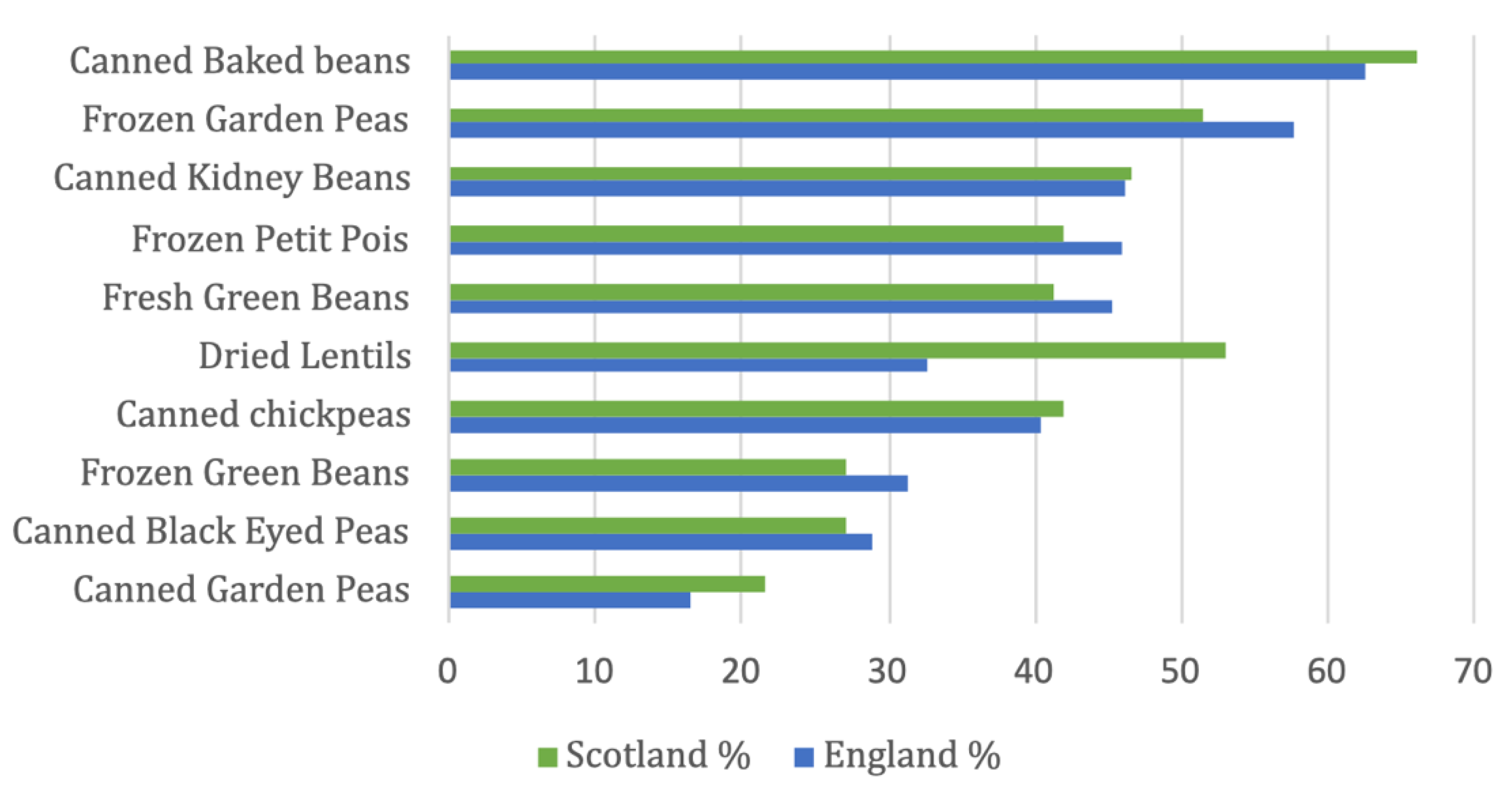

The three most frequently purchased wholefood plant proteins were canned baked beans (a traditional food item in the UK), frozen garden peas and canned kidney beans (Figure 2). Amongst the rest of the ten most frequently purchased wholefood proteins were kitchen staples such as frozen petit pois, fresh and frozen green beans, dried lentils, canned chickpeas, black eyed peas and garden peas. Green beans were the only fresh item, whereas half of food items were canned, falling under the processed food category [24]. Scottish people bought significantly more dried lentils (p < 0.001) than participants from England.

Figure 2.

Ten most frequently purchased wholefood plant proteins.

3.3. Sociodemographic Predictors of Plant-Protein Purchasing

3.3.1. Plant-Based Alternative Food Products

In a fully adjusted multivariate model an independent factor for purchasing PBAF was country of residence (Table 2). English participants were 32% more likely to purchase PBAF (p < 0.025). A further independent factor in the fully adjusted model was age. Participants from the Baby Boomer and Traditionalists age group were less likely to purchase PBAF (p < 0.001, p = 0.027). Moreover, participants with a Black/African or Caribbean background were more likely to purchase PBAF than White participants (OR 3.88, p = 0.008). Furthermore, Asian and multiple ethnicities or other were more likely to purchase PBAF than the white population (OR 2.28, p = 0.015; OR 2.72, p = 0.031).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic factors of PBAF purchasing.

3.3.2. Wholefood Plant Proteins

When examining the factors regarding the purchasing behaviour of wholefood plant protein products, as depicted in Table 3, the main factor with an overall significant effect in the multivariate model was IMD. Participants with low deprivation (IMD 1) were significantly more likely to purchase wholefood plant-proteins (OR 3.46, p = 0.001) than those from high deprivation (IMD 5). Moreover, people from the Baby Boomer generation were less likely to purchase wholefood plant-proteins than those in Generation Z (OR 0.38, p = 0.020). However, age did not have an overall effect in the multivariate analysis nor univariate analysis.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic factors of wholefood plant-protein purchasing.

3.3.3. Purchase-Amounts of PBAF and Wholefood Plant Protein Product Types

When examining the number of foods purchased from both PBAF and wholefood plant protein groups (Table 4), it could be seen that, overall, the population indicated they purchased an average of 2.06 PBAF product types (SD 3.21, median 0.00, interquartile range (IQR) 0, 3) and a mean of 6.92 products (SD 4.57, median 7, IQR 3, 11) of wholefood plant-proteins types in their general grocery shop (out of 18 PBAF and 24 wholefood plant-protein product categories to choose from in the survey). English participants purchased a median of 1 product (IQR 0, 3), whereas the median value for Scottish consumers was 0 (IQR 0, 3) with at statistically significant distribution (p = 0.022). Millennials and Generation Z purchased a mean of 2.55 (SD 2.26) and 2.66 (SD 3.70) products (both with a median of 1, IQR 0, 4), whereas Generation X, Baby Boomers and Traditionalists averaged at 2.17 (SD 3.36, median 0, IQR 0, 3), 1.18 (SD 2.43, median 0, IQR 0, 1) and 0.98 (SD 2.14, median 0, IQR 0, 1) products respectively and the difference in this distribution was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Distribution of Purchase Amounts of product types within sociodemographic groups.

Furthermore, the median purchasing score for wholefood plant-protein types from individuals from low deprivation had a median (IQR) of 8 (5,11) items, whereas individuals from high deprivation had a median of 6 (IQR 3, 11) and overall, the distribution across different IMD groups was found to be significant (p = 0.013). This suggests significantly different purchasing patterns between IMD groups.

3.4. Protein Knowledge

Overall, 69.8% of participants recognised lentils as a good source of protein. Also, 88.5% of participants agreed that protein is important for a healthy body and 87% saw protein as important for body muscle. However only 58.5% recognized eating a more plant-based diet as healthy and only 65.8% see eating a plant-based diet as being good for the planet.

When comparing different sociodemographic factors with agreement to protein knowledge statements (Table 5), it was evident that people from low deprivation areas (IMD 1) are significantly more likely to recognise lentils as a good source of protein (OR 1.94, p = 0.003) and more likely to recognise a plant-based diet as being healthy (OR 1.79, p = 0.004) than participants from high deprivation areas (IMD 5). A further independent factor affecting protein knowledge in the different multivariate models was gender. Females were more likely to agree that lentils are a good source of protein (OR 1.7, p < 0.001), more likely to see a plant-based diet as being good for the planet (OR 1.51, p = 0.002) and more likely to recognise a plant-based diet as being healthy (OR 1.59, p < 0.001) than men. Finally living in Scotland increased the odds of recognising lentils as good source of protein and participants from England were less likely to recognise lentils as good source of protein (OR 0.75, p = 0.028).

Table 5.

Sociodemographic groupings showing agreement with statements about protein-multivariate model analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. PBAF as Ultra-Processed Plant-Based Food

The current study shares novel data from the UK about plant protein purchase behaviours and attitudes, with emphasis on geographical region and SES for PBAF. The self-reported behaviour revealed that purchasing rates for PBAF were relatively high, with 47.4% placing itself between values of a previous UK survey, where 13.1% reported to consume PBAF, from the National Diet and Nutrition survey (NDNS) between 2017–2019 [12]. More recent market research, from 2022, reports that around 65% UK consumers have tried meat-free foods [25]. However, self-reported purchasing does not necessarily translate to actual consumption, and this is a limitation of the current study. When it comes to sustainable food intentions and behaviours, the apparent contradiction between what consumers say and do, has been described as the ‘say-do’ gap [26]. Although intentions are a significant predictor of sustainable behaviour, the solution to this issue is combined data on self-reported attitudes on PBAF, that also link to purchasing behaviour and consumption patterns. Additionally, Culliford and Bradbury [27] and Panzone et al. [28] also suggest that intended sustainable beliefs and shopping baskets do not necessarily match, because consumers are unaware of how their shopping habits are not always in line with actual environmental benefit. When comparing the current results for PBAF items, a recent observational study identified a trend for plant-based burgers, sausages and mince to be the most popular plant-based meat alternatives [29]. This could be because more and more consumers are open to the idea of purchasing meat-free alternatives, that are similar to a meat product, with reasons supporting choice, ranging from health or environmentalism [7]. These PBAF, especially meat substitutes, pose as a large economic opportunity for retailers and producers, with sales revenues consistently rising into the billions [30]. Recently, to promote plant-based eating and increase sales, PBAF products are being more strategically placed (adjacent to, or integrated into, the meat aisles) on UK shop floors. This follows examples from intervention studies that found an increase in sales [31,32]. However, these popular plant-based burgers and sausages can be classed as ultra-processed foods, following the NOVA classification [24,33]. Being an industrially modified food substance with additives [24] these ultra-processed foods bear the risks of being high in salt, fat or sugar. A recent cross-sectional study analysing plant-based meats in the UK, found plant-based meat products to have significantly higher salt levels in five out of six examined categories than their meat-counterpart products, and nearly 75% of plant-based products not achieving national salt reduction target recommendations. On the positive side, they were found to have significantly less saturated fat, total fat and significantly more fibre [34]. In another study in Australia, similar results for a more favourable nutrient profile in terms of fats and fibre were found. However, only 55% of plant-based sausages were found to meet reformulation targets for salt, whereas it was met in 90% of plant-based crumbed/battered meat/poultry products [35]. An online audit in Ireland showed plant-based products to be similar or higher in salt than meat products, but again a source of fibre and lower in saturated fat, total fat and energy [36]. Finally in Sweden similar advantages and disadvantages were shown, of plant-based meat alternatives being higher in fibre and lower in saturated fats, but both meat and plant-based products can contribute highly to intakes of salt within recommended intake levels [37].

Products that are labelled as environmentally sustainable may not support healthier food choices. Despite having lower GHG emissions and incorporating ingredients that are favourable in terms of environmental sustainability, there is a need to clearly identify their health benefits and nutritional content [38].

4.2. Wholefood Plant Protein (Legume) Purchasing and Food Inequality

Substantial evidence exists which highlights the link between food inequality, socio-economic background and poor diet, mostly focused on fruit and vegetable consumption [16]. The evidence base identifies low-socioeconomic background as the “single most consistent risk factor for an unhealthy diet” [17]. The present study also suggests that a link exists between purchasing of wholefood plant proteins, specifically legumes and socio-economic background, when applying IMD score. Food and health inequalities are apparent in the UK, with adults and children from more deprived areas having diets lower in diet quality, with lower intakes of fibre, vegetables, fruit and oily fish [4,18]. This study did not try to quantify the amounts purchased nor consumed across IMD area, and further data is needed to assess intake of legumes in the UK, as well as associated sociodemographic factors including deprivation. To study the issue of deprivation affecting intake of legumes in more detail further research and data would be needed regarding education, employment, income and urban/rural location. We have previously reported intake data, from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) program, running 2008–2019, mean (SD) legume intake within the United Kingdom was 26.7 ± 29.6 g/day [39]. Legumes are not the first choice of protein source for people transitioning to a plant-based diet and the current data also support the notion that PBAF that mimic meat products, such as burgers and sausages, require less cooking skills. In their recent study, Alae-Carew et al. report that beans and pulses were found to make up only 0.8% of total daily energy intake when analysing NDNS data from 2017–2019 [12]. Similarly, Lonnie et al. highlight NDNS data from 2013–2014 in their review, that plant-proteins in UK diets are mainly derived from cereal and cereal products (such as bread, pasta, rice) contributing up to 25% to daily protein intakes [40]. The inclusion of more wholefood protein sources such as beans and pulses would not only increase the sustainability of individual diets, but also provide the health benefits of legumes [41], as well as being an affordable wholefood option [42]. Legumes have more fibre than animal derived protein, and are higher in fibre and protein content when compared with commonly consumed cereals and grains [42]. In the UK, the wider population fails to meet recommended intakes of fruit, vegetables and fibre [43,44]. For example, a portion of cooked lentils acts as great source of protein, containing 7.6 g of protein as well as 1.9 g of dietary fibre [45] and can be counted as one of the five-a-day according to the Eatwell guide [46]. However, despite encouraging the consumption of plant-based protein sources, limited guidance is given by the Eatwell guide about recommended intakes [40]. The UK Vegetarian Society has recently published the Vegetarian Eatwell guide [47], to include guidance on beans and pulses for protein.

4.3. Knowledge and Food Choice

Purchase of wholefood plant-based proteins is associated with knowledge. We highlight in the current study that participants from the highest deprived population group recognised lentils (one of the wholefood protein purchasing options in the survey) significantly less as a source of protein, in contrast to participants from an area of low deprivation. However, food choice is affected by a multitude of factors, not only knowledge. Knowledge is amongst the cognitive factors of individual characteristics, next to food-related or societal characteristics that affect food choice [48]. The National Food Strategy reports that knowledge and cooking skills have decreased throughout our society due to the rise of pre-packaged, pre-prepared, convenient food items [4]. We report a significant effect for country, gender, and age regarding knowledge of lentils as source of protein in this study. Future research could not only focus on whether knowledge about plant protein options is present but also whether cooking or culinary skills are available to prepare these foods [40]. Moreover, consumers from areas of low deprivation were significantly more likely to recognise a plant-based diet as being healthy, compared to those from high deprivation areas. For gender, females were significantly more knowledgeable and more likely to recognise plant-based diets as healthy, than males. Lack of knowledge, or more specifically, low awareness of plant-based proteins is a barrier for consumption, highlighted in a recent systematic review [49]. Interestingly, a recent policy report highlighted that general public concerns still remain that a fully plant-based diet could be nutritionally inadequate [5]. Additionally, insufficient knowledge about the environmental sustainability benefits of plant-based diets and poor awareness about environmental impacts of meat-consumption have been repeatedly reported in the wider literature [15,50]. These pose as opportunities for targeted public health education [51]. Public health policy makers need to raise awareness and educate around the nutritional as well as environmental benefits of plant-based wholefoods, targeted for local communities facing food insecurity. This approach to support affordable, healthy, and environmentally sustainable foods will contribute to reducing the existing diet and health inequalities. It is recognised that there is cultural and geographical influence on food choice, and our current data would support future exploration of the reasons why age is a barrier for consumption of plant-based proteins. We have previously highlighted [50] that older age groups report the main obstacles for making plant protein and specifically legume protein their preference, as lack of trust in products, unethical production, poor sensory qualities in terms of product taste, and perceived lack of healthiness. Lower intakes of plant protein have been associated with being male, having a higher income, lower education level and not placing importance on healthy eating [52,53,54]. A rapid transformation to a predominately plant-based diet is unlikely to be feasible on the global scale. However, consumers are becoming increasingly aware of the health benefits of predominantly plant-based diets, which have been associated with lowering the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and all-cause mortality in prospective cohort studies [55,56,57,58,59]. Previous literature also suggests that information alone will not be enough to bring about changes in behavior; population-level sustainable dietary advice or interventions may not produce the same effects in high- and lower-income groups [60].

5. Conclusions

A limitation of this study is that it is based on a survey asking for self-reported behaviour and knowledge related to diet and health, posing a risk of reporting bias, as well as social desirability bias [61]. Furthermore, the survey could have been completed by someone who purchases plant-based foods for other members of their household, but not necessarily plant-based products for themselves. The nature of the questionnaire as a qualitative survey assessing reported purchasing, did not assess or quantify individual or household consumption. It also did not quantify specific quantities purchased or re-purchasing rates of individual or branded products.

This study highlights the need for further research in plant-based proteins in order to increase consumption of PBAF, to promote both public and planetary health. Understanding barriers to purchasing wholefood plant proteins will demand more understanding of the associated sociodemographic factors. More research is needed to provide evidence on the effect of deprivation and other sociodemographic variables affecting consumption of plant-based proteins such as legumes. To reduce food and health inequalities, requires sustained behaviour change towards healthier, more sustainable diets. The findings of this study contribute to the expanding evidence base for consumer knowledge and choice around plant-based alternative foods. We highlight the importance of social deprivation on food choice and how this contributes to food-based inequalities. Novel plant-based alternative food products are not necessarily environmentally sustainable and healthy. Due to lack of consumer knowledge, PBAF can be surrounded by a “health-halo” [62] when in fact they are often ultra- processed and high in salt. This poses not only as opportunity for further research but also as an opportunity for policy makers to continue to act and to work on implementing meaningful recommendations for accessible and affordable aspects of plant-based diets, targeted for communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu14214706/s1, S1: Survey Questions.

Author Contributions

A.M.J. and C.L.F. designed and implemented the survey and extracted the data. A.M.J., C.L.F. and M.M.E.B. developed the research question, and analysed the data. Statistician G.W.H. assisted with data analysis. M.M.E.B. drafted the paper and all authors contributed data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. A.M.J. is the guarantor. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Scottish Government from project B7-01 (2022–2027), supporting this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Rowett Institute Ethics Panel (protocol code 812, 25 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Contact Alex Johnstone for access to anonymised data.

Acknowledgments

Support for initial data analysis was given by Mary Kynn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Macdiarmid, J.I. The Food System and Climate Change: Are Plant-Based Diets Becoming Unhealthy and Less Environmentally Sustainable? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthelmie, R.J. Impact of Dietary Meat and Animal Products on GHG Footprints: The UK and the US. Climate 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Prospective Cohort Study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimbleby, H. The National Food Strategy—The Plan. Available online: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/ (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Sajeev, E.P.M.; Martin, R.; Waite, C.; Norman, M. Is the UK Ready for Plant-Based Diets? Global Food Security 2021. Available online: https://www.foodsecurity.ac.uk/blog/is-the-uk-ready-for-plant-based-diets/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health Effects of Dietary Risks in 195 Countries, 1990–2017, A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnie, M.; Johnstone, A.M. The Public Health Rationale for Promoting Plant Protein as an Important Part of a Sustainable and Healthy Diet. Nutr. Bull. 2020, 45, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Godinho, C.A.; Truninger, M. Reducing Meat Consumption and Following Plant-Based Diets: Current Evidence and Future Directions to Inform Integrated Transitions. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2019, 91, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-Based Diets: A Review of the Definitions and Nutritional Role in the Adult Diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant Proteins: Assessing Their Nutritional Quality and Effects on Health and Physical Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alae-Carew, C.; Green, R.; Stewart, C.; Cook, B.; Dangour, A.D.; Scheelbeek, P.F.D. The Role of Plant-Based Alternative Foods in Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems: Consumption Trends in the UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 151041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A Systematic Review on Consumer Acceptance of Alternative Proteins: Pulses, Algae, Insects, Plant-Based Meat Alternatives, and Cultured Meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Sabete, R.; Sabate, J. Consumer Attitudes Towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer Perception and Behaviour Regarding Sustainable Protein Consumption: A Systematic Review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S.; Nutrition and Consumer Protection Division; FAO. Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity: Directions and Solutions for Policy, Research and Action. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United Against Hunger, Rome, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. ISBN 978-92-5-107288-2. [Google Scholar]

- d’Angelo, C.; Gloinson, E.; Draper, A.; Guthrie, S. Food Consumption in the UK: Trends, Attitudes and Drivers; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https:/www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4379.html (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Maguire, E.R.; Monsivais, P. Socio-Economic Dietary Inequalities in UK Adults: An Updated Picture of Key Food Groups and Nutrients from National Surveillance Data. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banovic, M.; Arvola, A.; Pennanen, K.; Duta, D.E.; Brückner-Gühmann, M.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Grunert, K.G. Foods with Increased Protein Content: A Qualitative Study on European Consumer Preferences and Perceptions. Appetite 2018, 125, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualtrics, Online Research Panels & Samples for Surveys. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/research-services/online-sample/ (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. English Indices of Deprivation 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Waters, J.A. Model of the Dynamics of Household Vegetarian and Vegan Rates in the UK. Appetite 2018, 127, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunsch, N.G. Veganism and Vegetarianism in the UK. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7297/veganism-in-the-united-kingdom/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods: What They Are and How to Identify Them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintel Press Team. Plant-Based Push: UK Sales of Meat-Free Foods Shoot Up. Available online: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/food-and-drink/plant-based-push-uk-sales-of-meat-free-foods-shoot-up-40-between-2014-19 (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Reynolds, C.; Moore, S.; Denton, P.; Jones, R.; Abdy Collins, C.; Droulers, C.; Oakden, L.; Hegarty, R.; Snell, J.; Chalmers, H.; et al. A Rapid Evidence Assessment of UK Citizen and Industry Understandings of Sustainability; Food Standards Agency: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.food.gov.uk/research/wider-consumer-interests/a-rapid-evidence-assessment-of-uk-citizen-and-industry-understandings-of-sustainability (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Culliford, A.; Bradbury, J. A Cross-Sectional Survey of the Readiness of Consumers to Adopt an Environmentally Sustainable Diet. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzone, L.A.; Ulph, A.; Hilton, D.; Gortemaker, I.; Tajudeen, I.A. Sustainable by Design: Choice Architecture and the Carbon Footprint of Grocery Shopping. J. Public Policy Mark. 2021, 40, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estell, M.; Hughes, J.; Grafenauer, S. Plant Protein and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Consumer and Nutrition Professional Attitudes and Perceptions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global: Meat Substitutes Market Revenue 2016–2026. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/877369/global-meat-substitutes-market-value (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Piernas, C.; Cook, B.; Stevens, R.; Stewart, C.; Hollowell, J.; Scarborough, P.; Jebb, S.A. Estimating the Effect of Moving Meat-Free Products to the Meat Aisle on Sales of Meat and Meat-Free Products: A Non-Randomised Controlled Intervention Study in a Large UK Supermarket Chain. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Behavioural Insights Team. A Menu for Change. Available online: https://www.bi.team/publications/a-menu-for-change/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Gibney, M.J. Ultra-Processed Foods: Definitions and Policy Issues. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzy077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandrini, R.; Brown, M.K.; Pombo-Rodrigues, S.; Bhageerutty, S.; He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Nutritional Quality of Plant-Based Meat Products Available in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtain, F.; Grafenauer, S. Plant-Based Meat Substitutes in the Flexitarian Age: An Audit of Products on Supermarket Shelves. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safefood, Vegetarian Meat Substitutes. Available online: https://www.safefood.net/research-reports/vegetarian-meat-alternatives (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Bryngelsson, S.; Moshtaghian, H.; Bianchi, M.; Hallström, E. Nutritional Assessment of Plant-Based Meat Analogues on the Swedish Market. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Regional Office for Europe. Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of the Evidence: WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/349086 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Hartley, M.; Fyfe, C.L.; Wareham, N.J.; Khaw, K.-T.; Johnstone, A.M.; Myint, P.K. Association between Legume Consumption and Risk of Hypertension in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Norfolk Cohort. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnie, M.; Hooker, E.; Brunstrom, J.M.; Corfe, B.M.; Green, M.A.; Watson, A.W.; Williams, E.A.; Stevenson, E.J.; Penson, S.; Johnstone, A.M. Protein for Life: Review of Optimal Protein Intake, Sustainable Dietary Sources and the Effect on Appetite in Ageing Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Lam, H.-M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Varshney, R.K.; Colmer, T.D.; Cowling, W.; Bramley, H.; Mori, T.A.; Hodgson, J.M.; et al. Neglecting Legumes Has Compromised Human Health and Sustainable Food Production. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didinger, C.; Thompson, H.J. Defining Nutritional and Functional Niches of Legumes: A Call for Clarity to Distinguish a Future Role for Pulses in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDNS: Results from Years 9 to 11 (2016 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019). Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Health Survey for England 2019 [NS]. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2019 (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Finglas, P.M.; Roe, M.A.; Pinchen, H.M.; Berry, R.; Church, S.M.; Dodhia, S.K.; Powell, N.; Farron-Wilson, M.; McCardle, J.; Swam, G.; et al. McCance & Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods, 7th ed.; CPI Group: Croydon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide Booklet. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- The Vegetarian Society. Vegetarian Eatwell Guide. Available online: https://vegsoc.org/info-hub/health-and-nutrition/vegetarianeatwellguide/ (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Luxton, S. Alternative Protein Consumption: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1691–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBey, D.; Watts, D.; Johnstone, A.M. Nudging, Formulating New Products, and the Lifecourse: A Qualitative Assessment of the Viability of Three Methods for Reducing Scottish Meat Consumption for Health, Ethical, and Environmental Reasons. Appetite 2019, 142, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Aiking, H. “Meatless Days” or “Less but Better”? Exploring Strategies to Adapt Western Meat Consumption to Health and Sustainability Challenges. Appetite 2014, 76, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrin, T.; Papadopoulos, A. Understanding the attitudes and perceptions of vegetarian and plant-based diets to shape future health promotion programs. Appetite 2017, 109, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gavelle, E.; Davidenko, O.; Fouillet, H.; Delarue, J.; Darcel, J.; Huneau, J.-F.; Mariotti, F. Self-declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, A.; Drewnowski, A. Plant- and animal-protein diets in relation to JF.; sociodemographic drivers, quality, and cost: Findings from the Seattle Obesity Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Nishimura, K.; Barnard, N.D.; Takegami, M.; Watanabe, M.; Sekikawa, A.; Okamura, T.; Miyamoto, Y. Vegetarian diets and blood pressure: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.; Rexrode, K.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B. Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Steffen, L.N.; Coresh, J.; Rebholz, C.M. Plant-Based Diets Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality in a General Population of Middle-Aged Adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.J.; Horgan, G.W.; Whybrow, S.; Macdiarmid, J.I. Healthy and sustainable diets that meet greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and are affordable for different income groups in the UK. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1503–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althubaiti, A. Information Bias in Health Research: Definition, Pitfalls, and Adjustment Methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Berdzuli, N.; Rippin, H.; Farrand, C.; Halloran, A. The Shift to Plant-Based Diets: Are We Missing the Point? Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 29, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).