Breastfeeding Practices, Infant Formula Use, Complementary Feeding and Childhood Malnutrition: An Updated Overview of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

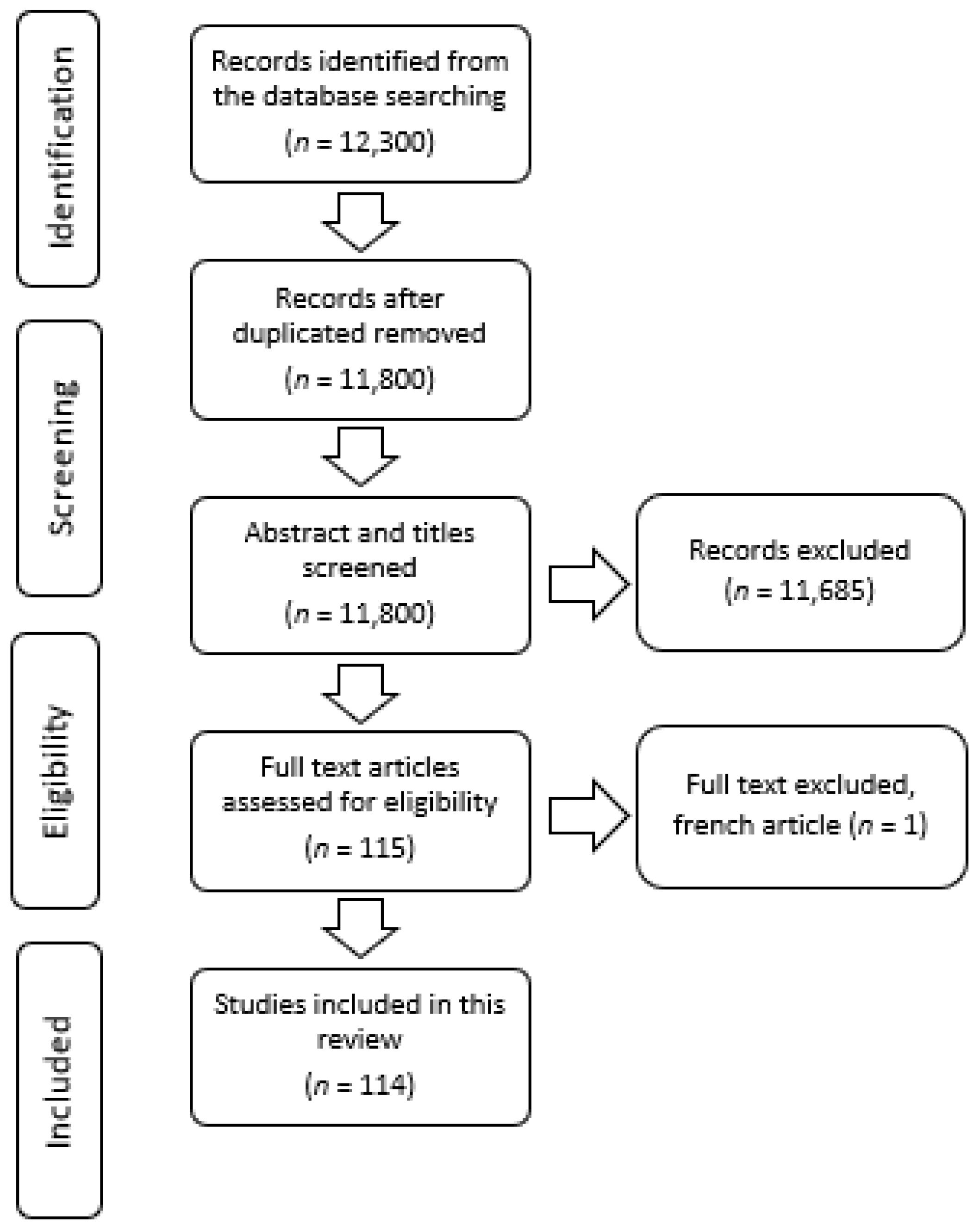

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Type of Studies and Participants

2.3. Type of Outcomes Reviewed

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in the EMR

3.1.1. Breastfeeding Parameters

Prevalence of Ever Breastfed

Prevalence of Exclusive Breastfeeding (under 6 Months)

Prevalence of Mixed Milk Feeding (under 6 Months)

Prevalence of Continued Breastfeeding (between 12–23 Months)

Prevalence of Bottle Feeding (under 6 Months)

3.1.2. Complementary Feeding Parameters

Prevalence of Introduction of Solid, Semi-Solid or Soft Food (at 6–8 Months)

3.2. Malnutrition Status among Under-5 Years Children in the EMR

3.2.1. Malnutrition Parameters

Undernutrition: Prevalence of Stunting, Underweight and Wasting

Overnutrition: Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity

3.3. International Overview

4. Discussion

4.1. Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices

4.2. Malnutrition Status among Under-5 Years Children

4.3. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) Report. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/publications/state-food-security-and-nutrition-world-sofi-report-2022 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Anonymous. WHO EMRO|Infant Nutrition|Health Topics. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/infant-nutrition/index.html (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Nasreddine, L.; Ayoub, J.J.; Al Jawaldeh, A. Review of the nutrition situation in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Ibrahim, C.; Saadeh, D.; Al-Jaafari, M.; Atwi, M.; Alasmar, S.; Najm, J.; Sacre, Y.; Hanna-Wakim, L.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. Correlates of Sub-Optimal Feeding Practices among under-5 Children amid Escalating Crises in Lebanon: A National Representative Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2022, 9, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Call to Action to Address: Maternal and Child Undernutrition in the Middle East and North Africa, Eastern Mediterranean and Arab Regions. 2022. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/nutrition/documents/call_to_action_mch_undernutrition_in_mena_emr_arab_regions_jun_2022.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Alemu, E.A. Malnutrition and Its Implications on Food Security; Zero hunger; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 509–518. [Google Scholar]

- Honja Kabero, T.; Bosha, T.; Feleke, F.W.; Haile Weldegebreal, D.; Stoecker, B. Nutritional Status and Its Association with Cognitive Function among School Aged Children at Soddo Town and Soddo Zuriya District, Southern Ethiopia: Institution Based Comparative Study. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2021, 8, 2333794X211028198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Neuringer, M.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Kuchan, M.J.; Renner, L.; Johnson, E.E.; Wang, X.; Kroenke, C.D. The effects of breastfeeding versus formula-feeding on cerebral cortex maturation in infant rhesus macaques. Neuroimage 2019, 184, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean WHO EMRO|Double Burden of Nutrition|Nutrition Site. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/nutrition/double-burden-of-nutrition/index.html (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Strategy on Nutrition for the Eastern Mediterranean Region 2020–2030. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330059 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- IPC Yemen: IPC Acute Malnutrition Analysis January 2020–March 2021|Issued in February 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-ipc-acute-malnutrition-analysis-january-2020-march-2021-issued-february-2021 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region Countries. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/countries.html (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Technical Note: How to Calculate Average Annual Rate of Reduction (AARR) of Underweight Prevalence. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/technical-note-calculate-average-annual-rate-reduction-aarr-underweight-prevalence/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Cheikh Ismail, L.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Ibrahim, S.; Ali, H.I.; Chokor, F.A.Z.; O’Neill, L.M.; Mohamad, M.N.; Kassis, A.; Ayesh, W.; Kharroubi, S. Nutritional status and adequacy of feeding Practices in Infants and Toddlers 0–23.9 months living in the United Arab Emirates (UAE): Findings from the feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) 2020. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Z.; Garemo, M.; Nanda, J. Patterns of breastfeeding practices among infants and young children in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2018, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredan, A.S.; Bshiwah, S.M.; Kumar, N.S. Infant-feeding practices among urban Libya women. Food Nutr. Bull. 1988, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.; Omer, F.; Al-Lenqawi, F.; Al-Awwa, R.; Khan, T.; El-Heneidy, A.; Kurdi, R.; Al-Jayyousi, G. Predictors of continued breastfeeding at one year among women attending primary healthcare centers in Qatar: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendaus, M.A.; Alhammadi, A.H.; Khan, S.; Osman, S.; Hamad, A. Breastfeeding rates and barriers: A report from the state of Qatar. Int. J. Women’s Health 2018, 10, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kohji, S.; Said, H.A.; Selim, N.A. Breastfeeding practice and determinants among Arab mothers in Qatar. Saudi Med. J. 2012, 33, 436–443. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Rahman, M.E.; El-Heneidy, A.; Benova, L.; Oakley, L. Early feeding practices and associated factors in Sudan: A cross-sectional analysis from multiple Indicator cluster survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.N.; Ariff, S.; Khan, U.; Habib, A.; Umer, M.; Suhag, Z.; Hussain, I.; Bhatti, Z.; Ullah, A.; Turab, A. Determinants of infant and young child feeding practices by mothers in two rural districts of Sindh, Pakistan: A cross-sectional survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Qureshi, Z.; Khan, K.A.; Gill, F.N. Patterns and determinants of breast feeding among mother infant pairs in dera ghazi Khan, Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2016, 28, 750–754. [Google Scholar]

- Hazir, T.; Akram, D.; Nisar, Y.B.; Kazmi, N.; Agho, K.E.; Abbasi, S.; Khan, A.M.; Dibley, M.J. Determinants of suboptimal breast-feeding practices in Pakistan. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, L.; Sabry, H.; Ismail, M.; Nasr, G. Pattern of infants’ feeding and weaning in Suez Governorate, Egypt: An exploratory study. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghwass, M.M.A.; Ahmed, D. Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding in a rural area in Egypt. Breastfeed. Med. 2011, 6, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shafei, A.M.H.; Labib, J.R. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods in rural Egyptian communities. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNIEF–Ministry of Health Sultanate Oman Oman National Nutrition Survey. Available online: https://groundworkhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ONNS_Report_2017.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Lebanon Nutrition Sector Lebanon-National SMART Survey Report. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/15741/file/National%20Nutrition%20SMART%20Survey%20Report%20.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Chehab, R.F.; Nasreddine, L.; Zgheib, R.; Forman, M.R. Exclusive breastfeeding during the 40-day rest period and at six months in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, M.; Khatoon, N.; Maclean, E.C.; Al-Hamad, N.; Mohammad, A.; Al-Wotayan, R.; Abraham, S. Infant and young child feeding patterns in Kuwait: Results of a cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2201–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.F.; Abdel Kader, A.M.; Al Refaee, F.A.; Mohammad, Y.A.; Dhafiri, S.A.; Gabr, S.; Al Qattan, S. Breastfeeding practice in Kuwait: Determinants of success and reasons for failure. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dashti, M.; Scott, J.A.; Edwards, C.A.; Al-Sughayer, M. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation among mothers in Kuwait. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2010, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank Exclusive Breastfeeding (% of Children under 6 Months). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.BFED.ZS (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Afghanistan. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/southern-asia/afghanistan/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- UNICEF Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Data. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/dataset/infant-young-child-feeding/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Na, M.; Aguayo, V.M.; Arimond, M.; Mustaphi, P.; Stewart, C.P. Predictors of complementary feeding practices in Afghanistan: Analysis of the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Djibouti. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/eastern-africa/djibouti/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Tawfik, S.; Saied, D.; Mostafa, O.; Salem, M.; Habib, E. Formula feeding and associated factors among a group of Egyptian mothers. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandeel, W.A.; Rabah, T.M.; Zeid, D.A.; El-Din, E.M.S.; Metwally, A.M.; Shaalan, A.; El Etreby, L.A.; Shaaban, S.Y. Determinants of Exclusive Breastfeeding in a Sample of Egyptian Infants. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1818–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Egypt. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/northern-africa/egypt/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Abou-ElWafa, H.S.; El-Gilany, A. Maternal work and exclusive breastfeeding in Mansoura, Egypt. Fam. Pract. 2019, 36, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.S.; Ghazawy, E.R.; Hassan, E.E. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of breastfeeding and weaning among mothers of children up to 2 years old in a rural area in El-Minia Governorate, Egypt. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2014, 3, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul-Fadl, A.M.; Al-yasin, S.; Al Jawaldeh, A. Complementary Feeding Practices and Nutritional Status of Children in Egypt: A regional assessment. Egypt. J. Breastfeed. 2019, 16, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zarshenas, M.; Zhao, Y.; Binns, C.W.; Scott, J.A. Baby-friendly hospital practices are associated with duration of full breastfeeding in primiparous but not multiparous Iranian women. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Iran. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/southern-asia/iran-islamic-republic/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Kelishadi, R.; Rashidian, A.; Jari, M.; Khosravi, A.; Khabiri, R.; Elahi, E.; Bahreynian, M. National survey on the pattern of breastfeeding in Iranian infants: The IrMIDHS study. Med. J. Islamic Rep. Iran 2016, 30, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Saki, A.; Eshraghian, M.R.; Tabesh, H. Patterns of daily duration and frequency of breastfeeding among exclusively breastfed infants in Shiraz, Iran, a 6-month follow-up study using Bayesian generalized linear mixed models. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olang, B.; Farivar, K.; Heidarzadeh, A.; Strandvik, B.; Yngve, A.; Sahlgrenska Akademin; Institute of Clinical Sciences; Institutionen för kliniska vetenskaper; Göteborgs universitet; Gothenburg University. Sahlgrenska Academy Breastfeeding in Iran: Prevalence, duration and current recommendations. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2009, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, H.S. Malnutrition trends in preschool children from a primary healthcare center in Baghdad: A comparative two-year study (2006 and 2012). Qatar Med. J. 2017, 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Iraq. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/iraq/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Obaid, K.A. Breast Feeding and Co-morbidities on Mothers and Infants in Two Main Hospitals of Diyala Province, Baquba, Iraq. Diyala J. Med. 2014, 7, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayalakshmi, P.; Susheela, T.; Mythili, D. Knowledge, attitudes, and breast feeding practices of postnatal mothers: A cross sectional survey. Int. J. Health Sci. 2015, 9, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdeeq, N.S.; Saleh, A.M. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice for the first six months in mothers with infants between 6 and 15 months of age in Erbil city, Iraq: A cross-sectional study. Zanco J. Med. Sci. 2021, 25, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, W.; Khasawneh, A.A. Predictors and barriers to breastfeeding in north of Jordan: Could we do better? Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Jordan. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/jordan/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Altamimi, E.; Al Nsour, R.; Al Dalaen, D.; Almajali, N. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of breastfeeding among working mothers in South Jordan. Workplace Health Saf. 2017, 65, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuidhail, J.; Al-Modallal, H.; Yousif, R.; Almresi, N. Exclusive breast feeding (EBF) in Jordan: Prevalence, duration, practices, and barriers. Midwifery 2014, 30, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, M.; Scott, J.A.; Edwards, C.A.; Al-Sughayer, M. Predictors of breastfeeding duration among women in Kuwait: Results of a prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2014, 6, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, L.; Hobeika, M.; Zeidan, R.K.; Salameh, P.; Issa, C. Determinants of exclusive and mixed breastfeeding durations and risk of recurrent illnesses in toddlers attending day care programs across Lebanon. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, e24–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akik, C.; Ghattas, H.; Filteau, S.; Knai, C. Barriers to breastfeeding in Lebanon: A policy analysis. J. Public Health Policy 2017, 38, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi Khalil, H.; Hawi, M.; Hoteit, M. Feeding Patterns, Mother-Child Dietary Diversity and Prevalence of Malnutrition among Under-Five Children in Lebanon: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Retrospective Recall. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 815000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Lebanon. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/lebanon/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Batal, M.; Boulghourjian, C.; Akik, C. Complementary feeding patterns in a developing country: A cross-sectional study across Lebanon. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2010, 16, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Nutrition in Times of Crises—Lebanon. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/15746/file/Nutrition%20in%20Times%20of%20Crisis.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Abdulmalek, L.J. Factors affecting exclusive breast feeding practices in Benghazi, Libya. Breast 2018, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, M.; Laamiri, F.Z.; Aguenaou, H.; Doukkali, L.; Mrabet, M.; Barkat, A. The impact of maternal socio-demographic characteristics on breastfeeding knowledge and practices: An experience from Casablanca, Morocco. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2018, 5, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Morocco. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/northern-africa/morocco/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Al Maamari, S.; Al Shammakhi, S.; Alghamari, I.; Jabbour, J.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. Young children feeding practices: An update from the sultanate of Oman. Children 2021, 8, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Oman. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/oman/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ariff, S.; Saddiq, K.; Khalid, J.; Sikanderali, L.; Tariq, B.; Shaheen, F.; Nawaz, G.; Habib, A.; Soofi, S.B. Determinants of infant and young complementary feeding practices among children 6–23 months of age in urban Pakistan: A multicenter longitudinal study. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Pakistan. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/southern-asia/pakistan/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- UNICEF Pakistan National Nutrition Survey 2018—Key Findings Report. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/media/1951/file/Final%20Key%20Findings%20Report%202019.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles—State of Palestine. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/state-palestine/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Musmar, S.G.; Qanadeelu, S. Breastfeeding patterns among Palestinian infants in the first 6 months in Nablus refugee camps: A cross-sectional study. J. Hum. Lact. 2012, 28, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, S.M.; El Sayed, N.A.; Nofal, L.M.; Abdeen, Z.A. Ongoing deterioration of the nutritional status of Palestinian preschool children in Gaza under the Israeli siege. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2013, 19, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, S.; Mourad, T.A.; Papandreou, C. Nutritional status of Palestinian children attending primary health care centers in Gaza. Indian J. Pediatr. 2009, 76, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Qatar. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/qatar/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Omar, A.A.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Qurachi, M.M. Trends in infant nutrition in Saudi Arabia: Compliance with WHO recommendations. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousefi, N.A. Determinants of successful exclusive breastfeeding for Saudi mothers: Social acceptance is a unique predictor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, M.A.; Allebdi, M.; Almohammadi, M.; Alnafie, A.; Al-Hazmi, L.; Alyoubi, S. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in relation to knowledge, attitude and practice of breastfeeding mothers in Rabigh community, Western Saudi Arabia. World J. Pediatr. 2019, 15, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Child Health in Somalia: Situation Analysis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Somalia. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/eastern-africa/somalia/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Abu-Manga, M.; Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Qureshi, A.B.; Ali, A.M.E.; Pizzol, D.; Dureab, F. Nutrition assessment of under-five children in sudan: Tracking the achievement of the global nutrition targets. Children 2021, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, A.A.; Bushara, S.O.; Elmadhoun, W.M.; Noor, S.K.; Abdelkarim, M.; Aldeen, I.N.; Osman, M.M.; Almobarak, A.O.; Awadalla, H.; Ahmed, M.H. Prevalence and determinants of undernutrition among children under 5-year-old in rural areas: A cross-sectional survey in North Sudan. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Sudan. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/northern-africa/sudan/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles—Syrian Arab Republic. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/syrian-arab-republic/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Tunisia. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/northern-africa/tunisia/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Al Ketbi, M.I.; Al Noman, S.; Al Ali, A.; Darwish, E.; Al Fahim, M.; Rajah, J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of breastfeeding among women visiting primary healthcare clinics on the island of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2018, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Yemen. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/yemen/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- The World Bank Prevalence of Wasting, Weight for Height (% of Children under 5). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.WAST.ZS (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Al-Zangabila, K.; Adhikari, S.P.; Wang, Q.; Sunil, T.S.; Rozelle, S.; Zhou, H. Alarmingly high malnutrition in childhood and its associated factors: A study among children under 5 in Yemen. Medicine 2021, 100, e24419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyoki, D.K.; Berkley, J.A.; Moloney, G.M.; Kandala, N.; Noor, A.M. Predictors of the risk of malnutrition among children under the age of 5 years in Somalia. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3125–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiarie, J.; Karanja, S.; Busiri, J.; Mukami, D.; Kiilu, C. The prevalence and associated factors of undernutrition among under-five children in South Sudan using the standardized monitoring and assessment of relief and transitions (SMART) methodology. BMC Nutr. 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menghwar, B.; Laghari, Z.A.; Memon, S.F.; Warsi, J.; Shaikh, S.A.; Baig, N.M. Prevalence of malnutrition in children under five years’ age in District Tharparkar Sindh, Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahsan, S.; Mansoori, N.; Mohiuddin, S.M.; Mubeen, S.M.; Saleem, R.; Irfanullah, M. Frequency and determinants of malnutrition in children aged between 6 to 59 months in district Tharparkar, a rural area of Sindh. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2017, 67, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Frozanfar, M.K.; Yoshida, Y.; Yamamoto, E.; Reyer, J.A.; Dalil, S.; Rahimzad, A.D.; Hamajima, N. Acute malnutrition among under-five children in Faryab, Afghanistan: Prevalence and causes. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2016, 78, 41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The World Bank Prevalence of Underweight, Weight for Age (% of Children under 5). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MALN.ZS (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Rashad, A.S.; Sharaf, M.F. Economic growth and child malnutrition in Egypt: New evidence from national demographic and health survey. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 135, 769–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, E.T.; Marie-Françoise, R.; Salaheddin, M.M.; Najeeb, E.; Monem Ahmed, A.; Ibrahim, B.; Gerard, L. Nutritional status of under-five children in Libya; a national population-based survey. Libyan J. Med. 2008, 3, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghabozorgi, A.R.; Safari, S.; Khadivi, R. The prevalence rate of malnutrition in children younger than 5 in Iran in 2018. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 12, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanihashemi, H.; Noroozi, M.; Zavoshy, R.; Afkhamrezaei, A.; Jalilolghadr, S.; Esmailzadehha, N. Malnutrition and birth related determinants among children in Qazvin, Iran. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- The World Bank Prevalence of Stunting, Height for Age (Modeled Estimate, % of Children under 5). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.STNT.ME.ZS (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Libya. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/northern-africa/libya/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- The World Bank Prevalence of Overweight (Modeled Estimate, % of Children under 5). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.OWGH.ME.ZS (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Al-Raees, G.Y.; Al-Amer, M.A.; Musaiger, A.O.; D’Souza, R. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children aged 2–5 years in Bahrain: A comparison between two reference standards. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2009, 4, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidlou, S.N.; Babaei, F.; Ayremlou, P. Malnutrition, overweight, and obesity among urban and rural children in north of west Azerbijan, Iran. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mokhallalati, Y.; FarajAllah, H.; Albarqouni, L. Socio-demographic and economic determinants of overweight and obesity in preschool children in Palestine: Analysis of data from the Palestinian Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Lancet 2019, 393, S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.; Hwalla, N.; Saliba, A.; Akl, C.; Naja, F. Prevalence and correlates of preschool overweight and obesity amidst the nutrition transition: Findings from a national cross-sectional study in Lebanon. Nutrients 2017, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Kuwait. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/kuwait/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Elsary, A.Y.; Abd El-moktader, A.M.; Alkassem Elgameel, W.; Mohammed, S.; Masoud, M.; Abd El-Haleem, N.G. Nutritional survey among under five children at Tamyia district in Fayoum, Egypt. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, A.A.; Rezapour, A.; Khosravi, A.; Abarghouei, V.A. Socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition in under-5 children in Iran: Evidence from the multiple indicator demographic and health survey, 2010. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2017, 50, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifzadeh, G.; Mehrjoofard, H.; Raghebi, S. Prevalence of malnutrition in under 6-year olds in South Khorasan, Iran. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2010, 20, 435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Payandeh, A.; Saki, A.; Safarian, M.; Tabesh, H.; Siadat, Z. Prevalence of malnutrition among preschool children in northeast of Iran, a result of a population based study. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, H.F.; Mustafa, J.; Aljunid, S.; Isa, Z.M.; Abdalqader, M.A. Malnutrition among 3 to 5 years old children in Baghdad city, Iraq: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2013, 31, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, I.H.; AL-Jubori, K.H.; Baiee, H.A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Under Nutrition among Under-Five Children in Babylon Province, Iraq, 2016. J. Univ. Babylon Pure Appl. Sci. 2018, 26, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaoud, N.; Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Al-Anazi, F.; Subhakaran, M.; Doggui, R. Trend and Causes of Overweight and Obesity among Pre-School Children in Kuwait. Children 2021, 8, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Taguri, A.; Betilmal, I.; Mahmud, S.M.; Ahmed, A.M.; Goulet, O.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S. Risk factors for stunting among under-fives in Libya. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albelbeisi, A.; Shariff, Z.M.; Mun, C.Y.; Abdul-Rahman, H.; Abed, Y. Growth patterns of Palestinian children from birth to 24 months. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishawi, E.; Rafiq, R.; Soo, K.L.; Abed, Y.A.; Muda, W.A.M.W. Prevalence and associated factors influencing stunting in children aged 2–5 years in the Gaza Strip-Palestine: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mouzan, M.I.; Foster, P.J.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Salloum, A.A.; Al Omar, A.A.; Qurachi, M.M. Prevalence of malnutrition in Saudi children: A community-based study. Ann. Saudi Med. 2010, 30, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles–Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/western-asia/saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Nassreddine, L.M.; Naja, F.A.; Hwalla, N.C.; Ali, H.I.; Mohamad, M.N.; Chokor, F.A.Z.S.; Chehade, L.N.; O’Neill, L.M.; Kharroubi, S.A.; Ayesh, W.H. Total Usual Nutrient Intakes and Nutritional Status of United Arab Emirates Children (<4 Years): Findings from the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) 2021. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare, M.; Sorić, M.; Bovet, P.; Miranda, J.J.; Bhutta, Z.; Stevens, G.A.; Laxmaiah, A.; Kengne, A.; Bentham, J. The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: A worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Infant and Young Child Feeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- It, M. How Milk Formula Companies are Putting Profits before Science. 2017. Available online: https://changingmarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Milking-it-Final-report-CM.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwaz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G. Breastfeeding 2: Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices. Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilloteau, P.; Zabielski, R.; Hammon, H.M.; Metges, C.C. Adverse effects of nutritional programming during prenatal and early postnatal life, some aspects of regulation and potential prevention and treatments. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 60, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balbus, J.M.; Barouki, R.; Birnbaum, L.S.; Etzel, R.A.; Gluckman Sr, P.D.; Grandjean, P.; Hancock, C.; Hanson, M.A.; Heindel, J.J.; Hoffman, K. Early-life prevention of non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2013, 381, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.A.; Vaz, J.S.; Maia, F.S.; Baker, P.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Piwoz, E.; Rollins, N.; Victora, C.G. Rates and time trends in the consumption of breastmilk, formula, and animal milk by children younger than 2 years from 2000 to 2019: Analysis of 113 countries. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Abul-Fadl, A. Assessment of the baby friendly hospital initiative implementation in the eastern Mediterranean region. Children 2018, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, C.A.; Hobbs, A.J.; McDonald, S.W.; Tough, S.C. Maternal perceptions of partner support during breastfeeding. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2013, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Breastfeeding Support in the Workplace. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/73206/file/Breastfeeding-room-guide.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Baker, P.; Santos, T.; Neves, P.A.; Machado, P.; Smith, J.; Piwoz, E.; Barros, A.J.; Victora, C.G.; McCoy, D. First-food systems transformations and the ultra-processing of infant and young child diets: The determinants, dynamics and consequences of the global rise in commercial milk formula consumption. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Getinet, T.; Solomon, S.; Jones, A.D. Prevalence of initiation of complementary feeding at 6 months of age and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6 to 24 months in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 2018, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker-Berbari, L.; Qahoush Tyler, V.; Akik, C.; Jamaluddine, Z.; Ghattas, H. Predictors of complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in five countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, M.V.; Ogbo, F.A.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Agho, K.E. Prevalence and factors associated with complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in India: A regional analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdurahman, A.A.; Chaka, E.E.; Bule, M.H.; Niaz, K. Magnitude and determinants of complementary feeding practices in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Awwad, N.J.; Ayoub, J.; Barham, R.; Sarhan, W.; Al-Holy, M.; Abughoush, M.; Al-Hourani, H.; Olaimat, A.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. Review of the Nutrition Situation in Jordan: Trends and Way Forward. Nutrients 2021, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO-UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group on Nutrition Monitoring (TEAM) Methodology for Monitoring Progress towards the Global Nutrition Targets for 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-17.9 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Vaivada, T.; Akseer, N.; Akseer, S.; Somaskandan, A.; Stefopulos, M.; Bhutta, Z.A. Stunting in childhood: An overview of global burden, trends, determinants, and drivers of decline. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 777S–791S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewnet, S.S.; Derseh, H.A.; Desyibelew, H.D.; Fentahun, N. Undernutrition and Associated Factors among Under-Five Orphan Children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 2021, 6728497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, C.M.; Hale, D.E.; Lynch, J.L. Pediatric obesity epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2011, 18, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lim, H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2012, 24, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Noncommunicable Diseases: Childhood Overweight and Obesity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/noncommunicable-diseases-childhood-overweight-and-obesity (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Khader, Y.; Irshaidat, O.; Khasawneh, M.; Amarin, Z.; Alomari, M.; Batieha, A. Overweight and obesity among school children in Jordan: Prevalence and associated factors. Matern. Child Health J. 2009, 13, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, T.T.; Al-Sultan, A.I.; Ali, A. Overweight and obesity and their association with dietary habits, and sociodemographic characteristics among male primary school children in Al-Hassa, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2008, 33, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.; Naja, F.; Akl, C.; Chamieh, M.C.; Karam, S.; Sibai, A.; Hwalla, N. Dietary, lifestyle and socio-economic correlates of overweight, obesity and central adiposity in Lebanese children and adolescents. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1038–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muhaimeed, A.A.; Dandash, K.; Ismail, M.S.; Saquib, N. Prevalence and correlates of overweight status among Saudi school children. Ann. Saudi Med. 2015, 35, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Implementing the WHO Recommendations on the Marketing of Food and Nonalcoholic Beverages to Children in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/nutrition/documents/who_recos_on_marketing_to_children_2018.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

| Eastern Mediterranean Countries | Number of Children * | Ever Breastfed (%) | Exclusive Breastfeeding (%) | Mixed Milk Feeding (%) | Continued Breastfeeding (%) | Bottle Feeding (%) | Introduction of Solid, Semi-Solid, or Soft Foods (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan (2015–2018) | 7963 | NA | 57.5 | NA | 73.8 | NA | 58.5 | [35,36,37,38] |

| Bahrain | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Djibouti (2012–2017) | ND | NA | 12.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | [35,39] |

| Egypt (2010–2018) | 7331 | 97.7 | 29.1 | 55.9 | 50.3 | 34 | 72.3 | [26,27,28,35,37,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| Iran (2005–2015) | 93,627 | 98.6 | 46 | 87 | 70.5 | 31.2 | 75.9 | [35,37,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Iraq (2006–2018) | 1598 | 88.5 | 30.1 | 26.1 | 35.4 | 32.6 | 82.5 | [35,37,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Jordan (2014–2017) | 1444 | 84.4 | 21.1 | 43 | 25.8 | NA | 83.4 | [35,37,56,57,58,59] |

| Kuwait (2007–2015) | 2726 | 93.6 | 26.5 | 50.4 | 12 | 16.7 | NA | [32,33,34,60] |

| Lebanon (2000–2021) | 9481 | 89.7 | 25.4 | 29.25 | 24.9 | 30.3 | 43.6 | [4,30,31,37,61,62,63,64,65,66] |

| Libya (1988–2017) | 526 | 95.6 | 41.3 | 26.5 | NA | 27 | NA | [18,67] |

| Morocco (2003–2017) | 271 | 94.7 | 42.4 | 39.4 | 41.2 | 30.3 | 84.4 | [35,37,68,69] |

| Oman (2016–2017) | 1344 | 47 | 24.6 | NA | 64.1 | 48.6 | 95.3 | [29,37,70,71] |

| Pakistan (2006–2018) | 26,872 | 96.8 | 37.2 | NA | 65.1 | 19.5 | 52.5 | [23,24,25,37,72,73,74] |

| Palestine (2003–2020) | 835 | NA | 43.8 | 41 | 30.4 | 23.2 | 89.9 | [35,37,75,76,77,78] |

| Qatar (2009–2017) | 1418 | 96 | 24.4 | 25.6 | 36.5 | NA | 74 | [19,20,21,35,37,79] |

| Saudi Arabia (2004–2019) | 16,258 | 91.6 | 21.9 | 42.3 | 11.1 | 59.2 | 14.3 | [80,81,82] |

| Somalia (2006–2018) | ND | NA | 25.5 | NA | 44.2 | NA | 41.2 | [35,37,83,84] |

| Sudan (2014–2019) | 152,259 | 96 | 55.6 | NA | 68.2 | NA | 54.7 | [22,35,37,85,86,87] |

| Syrian Arab Republic (2006–2019) | ND | NA | 28.5 | NA | 42.5 | NA | 74.6 | [35,37,88] |

| Tunisia (2018) | ND | NA | 13.5 | NA | NA | 16.7 | 86.8 | [35,37,89] |

| United Arab Emirates (2014–2020) | 2346 | 95.3 | 32.7 | 48 | 1 | NA | 93.5 | [16,17,90] |

| Yemen (2013) | ND | NA | 9.7 | NA | 60.5 | NA | 69.2 | [35,37,91] |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 326,299 | |||||||

| Point Estimate | 84.3 | 30.9 | 42.9 | 41.5 | 32.1 | 69.3 | ||

| Lower Limit | 47 | 9.7 | 25.6 | 1 | 16.7 | 14.3 | ||

| Upper Limit | 98.6 | 57.5 | 87 | 73.8 | 59.2 | 95.3 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Countries | Number of Children * | Stunting (%) | Underweight (%) | Wasting (%) | Overweight (%) | Obesity (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan (2018–2020) | 600 | 36.7 | 19.1 | 12.8 | 4 | NA | [36,92,98,99,104,106] |

| Bahrain (1995–2020) | 698 | 5.1 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 8.2 | 6.5 | [92,99,104,106,107] |

| Djibouti (2012–2020) | ND | 33.8 | 26 | 21.5 | 7.7 | NA | [39,92,99,104,106] |

| Egypt (2008–2020) | 5144 | 22.6 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 12.6 | NA | [42,45,92,99,100,104,106,112] |

| Iran (2004–2020) | 84,667 | 8.7 | 6.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 1.3 | [47,92,99,102,103,104,106,108,113,114,115] |

| Iraq (2006–2020) | 2290 | 25.4 | 9.9 | 4.2 | 7.5 | NA | [51,52,92,99,104,106,116,117] |

| Jordan (2012–2020) | ND | 7.5 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 5.9 | NA | [57,92,99,104,106] |

| Kuwait (2016–2020) | 4400 | 6.2 | 3 | 2.5 | 7.8 | 3.7 | [92,99,104,106,111,118] |

| Lebanon (2004–2021) | 11,505 | 9.7 | 4.4 | 6 | 14.6 | 4.3 | [4,30,63,64,66,92,99,104,106,110] |

| Libya (1995–2020) | 9846 | 30.8 | 8 | 8 | 23.7 | NA | [92,99,101,104,105,106,119] |

| Morocco (2016–2020) | 297 | 14.4 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 11.1 | NA | [68,69,92,99,104,106] |

| Oman (2016–2020) | 3129 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 4.5 | NA | [29,71,92,99,104,106] |

| Pakistan (2014–2020) | 93,159 | 46.8 | 35.6 | 13.8 | 5.1 | NA | [73,74,92,96,97,99,104,106] |

| Palestine (2003–2020) | 10,677 | 16.2 | 10.8 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 1.5 | [75,77,78,92,99,104,106,109,120,121] |

| Qatar (1995–2020) | ND | 4.6 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 13.9 | NA | [92,99,104,106] |

| Saudi Arabia (2004–2020) | 15,516 | 8 | 6.1 | 11.1 | 6.9 | NA | [92,99,104,106,122,123] |

| Somalia (2006–2020) | 73,778 | 31.4 | 29.3 | 15.4 | 3 | NA | [83,84,92,94,95,96,97,98,99,104,106] |

| Sudan (2010–2020) | 146,797 | 34.2 | 25.5 | 15.4 | 3.4 | 0.9 | [85,86,87,92,95,99,104,106] |

| Syrian Arab Republic (2010–2020) | ND | 28.8 | 10.4 | 11.5 | 18.1 | NA | [88,92,99,104,106] |

| Tunisia (2018–2020) | ND | 8.5 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 16.9 | NA | [89,92,99,104,106] |

| United Arab Emirates (2019–2020) | 801 | 12.5 | NA | 7 | 5 | 3 | [16,124] |

| Yemen (2013–2020) | 13,624 | 43.5 | 39 | 16.3 | 2.6 | NA | [91,92,93,99,104,106] |

| tern Mediterranean Region | 476,928 | ||||||

| Point Estimate | 20.3 | 13.1 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 3 | ||

| Lower Limit | 4.6 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 0.9 | ||

| Upper Limit | 46.8 | 39 | 21.5 | 23.7 | 6.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibrahim, C.; Bookari, K.; Sacre, Y.; Hanna-Wakim, L.; Hoteit, M. Breastfeeding Practices, Infant Formula Use, Complementary Feeding and Childhood Malnutrition: An Updated Overview of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194201

Ibrahim C, Bookari K, Sacre Y, Hanna-Wakim L, Hoteit M. Breastfeeding Practices, Infant Formula Use, Complementary Feeding and Childhood Malnutrition: An Updated Overview of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape. Nutrients. 2022; 14(19):4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194201

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbrahim, Carla, Khlood Bookari, Yonna Sacre, Lara Hanna-Wakim, and Maha Hoteit. 2022. "Breastfeeding Practices, Infant Formula Use, Complementary Feeding and Childhood Malnutrition: An Updated Overview of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape" Nutrients 14, no. 19: 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194201

APA StyleIbrahim, C., Bookari, K., Sacre, Y., Hanna-Wakim, L., & Hoteit, M. (2022). Breastfeeding Practices, Infant Formula Use, Complementary Feeding and Childhood Malnutrition: An Updated Overview of the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape. Nutrients, 14(19), 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194201