The Impact of COVID-19-Related Living Restrictions on Eating Behaviours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

3. Results

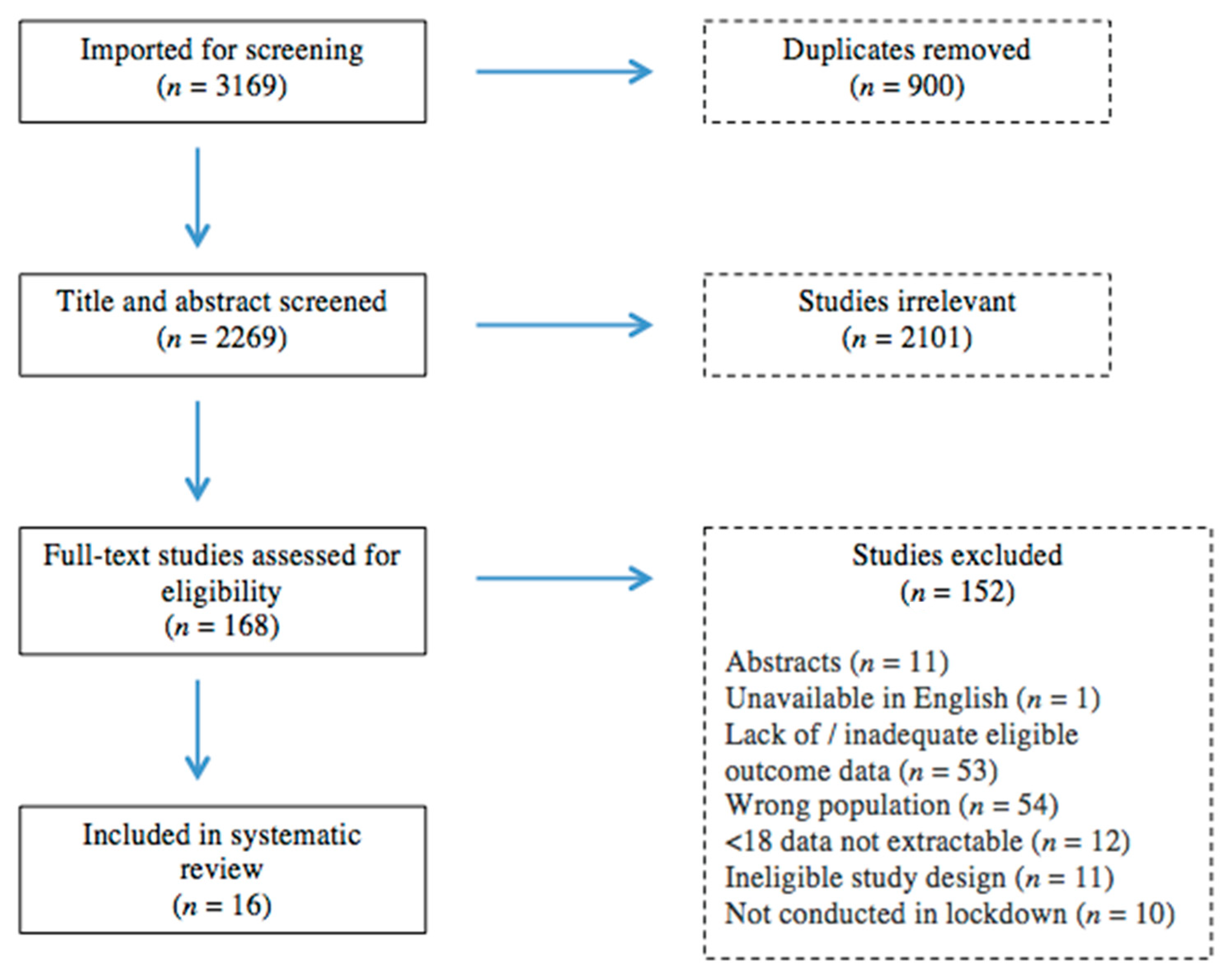

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Changes in Eating Behaviours among Children and Adolescents Observed during the COVID-19 Lockdown

3.4. Potential Explanations for Eating Changes

3.4.1. Age

3.4.2. Sex

3.4.3. Socioeconomic Status

3.4.4. Other Family Factors

3.4.5. Mood/Anxiety

3.4.6. Social Media Use

3.4.7. Shopping/Food Choice Patterns

3.4.8. Weight and BMI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks--the-media-briefing-on-COVID-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Chatterjee, K.; Chauhan, V. Epidemics, quarantine and mental health. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2020, 76, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zürcher, S.J.; Kerksieck, P.; Adamus, C.; Burr, C.M.; Lehmann, A.I.; Huber, F.K.; Richter, D. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems During Virus Epidemics in the General Public, Health Care Workers and Survivors: A Rapid Review of the Evidence. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 560389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, G.M.d.J.; Tavares, V.D.D.O.; Grilo, M.L.P.d.M.; Coelho, M.L.G.; de Lima-Araújo, G.L.; Schuch, F.B.; Galvão-Coelho, N.L. Mental Health in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Review of Prevalence Meta-Analyses. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 703838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batteux, E.; Taylor, J.; Carter, H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult mental health in the UK: A rapid systematic review. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Metcalfe, J.J.; Folta, S.C.; Brown, A.; Fiese, B. Diet and Health Benefits Associated with In-Home Eating and Sharing Meals at Home: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, R.P.P.; Mengelkoch, S.; Gassen, J.; Ellis, B.J.; Russell, E.M.; Hill, S.E. Low socioeconomic status and eating in the absence of hunger in children aged 3–14. Appetite 2020, 154, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite 2015, 86, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnariu, C.D.; Ilies, A.; Furtunescu, F.L. Influence of family modelling on children’s healthy eating behaviour. Rev. De Cercet. Si Interv. Soc. 2013, 41, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Salvy, S.J.; de la Haye, K.; Bowker, J.C.; Hermans, R.C. Influence of peers and friends on children’s and adolescents’ eating and activity behaviors. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, E.; Rolfes, S. Life cycle nutrition: Infancy, childhood and adolescence. In Understanding Nutrition, 9th ed.; Wadsworth/Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 560–561. [Google Scholar]

- Micali, N.; De Stavola, B.; Ploubidis, G.; Simonoff, E.; Treasure, J.; Field, A.E. Adolescent eating disorder behaviours and cog-nitions: Gender-specific effects of child, maternal and family risk factors. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussières, E.-L.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Meilleur, A.; Mastine, T.; Hérault, E.; Chadi, N.; Montreuil, M.; Généreux, M.; Camden, C.; Team, P.-C.; et al. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 691659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaabane, S.; Doraiswamy, S.; Chaabna, K.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. The Impact of COVID-19 School Closure on Child and Adolescent Health: A Rapid Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nearchou, F.; Flinn, C.; Niland, R.; Subramaniam, S.S.; Hennessy, E. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Outcomes in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Heal. 2021, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.A.; Hartman-Munick, S.M.; Kells, M.R.; Milliren, C.E.; Slater, W.A.; Woods, E.R.; Forman, S.F.; Richmond, T.K. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Number of Adolescents/Young Adults Seeking Eating Disorder-Related Care. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2021, 69, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Barazzoni, R.; Bischoff, S.C.; Breda, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Chourdakis, M. Impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on body weight: A combined systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 21, 00207-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Digital Data. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-child-measurement-programme/2020-21-school-year/age (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- CDC Obesity Data. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/children-obesity-COVID-19.html (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A.K.; Sofi, N.Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Ortiz-Pinto, M.A.; de Miguel-García, S.; Ortiz-Marrón, H.; Ortega-Torres, A.; Cabañas, G.; Gutiérrez–Torres, L.F.; Quiroga–Fernández, C.; Ordobás-Gavin, M.; Galán, I. Childhood obesity and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spettigue, W.; Obeid, N.; Erbach, M.; Feder, S.; Finner, N.; Harrison, M.E.; Isserlin, L.; Robinson, A.; Norris, M.L. The impact of COVID-19 on adolescents with eating disorders: A cohort study. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broomfield, A.S.; Rodd, I.; Winckworth, L. 1225 Paediatric eating disorder presentations to a district general hospital prior to, and during, the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, A281–A282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England, NHS Treating Record Number of Young People for Eating Disorders. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2022/03/nhs-treating-record-number-of-young-people-for-eating-disorders (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- PROSPERO Registration. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=251515 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence-Better Systematic Review Management. 2016. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Critical Appraisal Tools, JBI. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Aguilar-Martínez, A.; Bosque-Prous, M.; González-Casals, H.; Colillas-Malet, E.; Puigcorbé, S.; Esquius, L.; Espelt, A. Social Inequalities in Changes in Diet in Adolescents during Confinement Due to COVID-19 in Spain: The DESKcohort Project. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastorci, F.; Piaggi, P.; Doveri, C.; Trivellini, G.; Casu, A.; Pozzi, M.; Vassalle, C.; Pingitore, A. Health-Related Quality of Life in Italian Adolescents During Covid-19 Outbreak. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 611136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, M.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Oses, M.; Arenaza, L.; Amasene, M.; Labayen, I. Changes in lifestyle behaviours during the COVID -19 confinement in Spanish children: A longitudinal analysis from the MUGI project. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 16, e12731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, S.; Sperandei, S.; Freebairn, L.; Conroy, E.; Jani, H.; Marjanovic, S.; Page, A. The Impact of Physical Distancing Policies During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health and Well-Being Among Australian Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2020, 67, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.; Marchant, E.; Defeyter, M.A.; Woodside, J.; Brophy, S. Impact of school closures on the health and well-being of primary school children in Wales UK: A routine data linkage study using the HAPPEN Survey (2018–2020). BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, D.M.; Min, C.; Choi, H.G. Changes in Dietary Habits and Exercise Pattern of Korean Adolescents from Prior to during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuszczki, E.; Bartosiewicz, A.; Pezdan-Śliż, I.; Kuchciak, M.; Jagielski, P.; Oleksy, Ł.; Stolarczyk, A.; Dereń, K. Children’s Eating Habits, Physical Activity, Sleep, and Media Usage before and during COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hourani, H.; Alkhatib, B.; Abdullah, M. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Body Weight, Eating Habits, and Physical Activity of Jordanian Children and Adolescents. Disaster Med. Public Heal. Prep. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Androutsos, O.; Perperidi, M.; Georgiou, C.; Chouliaras, G. Lifestyle Changes and Determinants of Children’s and Adolescents’ Body Weight Increase during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Greece: The COV-EAT Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horikawa, C.; Murayama, N.; Kojima, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Morisaki, N. Changes in Selected Food Groups Consumption and Quality of Meals in Japanese School Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołota, A.; Głąbska, D. COVID-19 Pandemic and Remote Education Contributes to Improved Nutritional Behaviors and Increased Screen Time in a Polish Population-Based Sample of Primary School Adolescents: Diet and Activity of Youth during COVID-19 (DAY-19) Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, C.; Andrianou, X.D.; Constantinou, A.; Perikkou, A.; Markidou, E.; Christophi, C.A.; Makris, K.C. Exposome changes in primary school children following the wide population non-pharmacological interventions implemented due to COVID-19 in Cyprus: A national survey. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 32, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzi, S.; Sansò, A.; Pace, C.S. What’s Happened to Italian Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Preliminary Study on Symptoms, Problematic Social Media Usage, and Attachment: Relationships and Differences With Pre-pandemic Peers. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 590543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A.; Radwan, E.; Radwan, W. Eating habits among primary and secondary school students in the Gaza Strip, Palestine: A cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite 2021, 163, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segre, G.; Campi, R.; Scarpellini, F.; Clavenna, A.; Zanetti, M.; Cartabia, M.; Bonati, M. Interviewing children: The impact of the COVID-19 quarantine on children’s perceived psychological distress and changes in routine. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zhang, D.; Yu, W.; Luo, M.; Yang, S.; Jia, P. Impacts of lockdown on dietary patterns among youths in China: The COVID-19 Impact on Lifestyle Change Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3221–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E.M.; Rauber, F.; Costa, C.; Leite, M.A.; Gabe, K.T.; Louzada, M.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Dietary changes in the NutriNet Brasil cohort during the covid-19 pandemic. Rev. De Saude Publica. 2020, 54, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Gianzo Citores, M.; Hervás Bárbara, G.; Ruiz-Litago, F.; Casis Sáenz, L.; Arija, V.; López-Sobaler, A.M.; Martínez de Victoria, E.; Ortega, R.M.; Partearroyo, T.; et al. Patterns of Change in Dietary Habits and Physical Activity during Lockdown in Spain Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, D.; Guidetti, M.; Capasso, M.; Cavazza, N. Finally, the chance to eat healthily: Longitudinal study about food consumption during and after the first COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Food Qual. Preference 2021, 95, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Montes, E.; Uzhova, I.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Kapsokefalou, M.; Malisova, O.; Vlassopoulos, A.; Katidi, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 confinement on eating behaviours across 16 European countries: The COVIDiet cross-national study. Food Qual. Preference 2021, 93, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Ruíz-López, M.D. Changes in Dietary Behaviours during the COVID-19 Outbreak Confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Costanzo, S.; Ruggiero, E.; Persichillo, M.; Esposito, S.; Olivieri, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; et al. Changes in ultra-processed food consumption during the first Italian lockdown following the COVID-19 pandemic and major correlates: Results from two population-based cohorts. Public Heal. Nutr. 2021, 24, 3905–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, J.; Kandiah, J.; Saiki, D. The COVID-19 Pandemic, Stress, and Eating Practices in the United States. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh Ismail, L.; Osaili, T.M.; Mohamad, M.N.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Jarrar, A.H.; Abu Jamous, D.O.; Magriplis, E.; Ali, H.I.; Al Sabbah, H.; Hasan, H.; et al. Eating Habits and Lifestyle during COVID-19 Lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, E.C.; Wyszyńska, J.; Leszczak, J.; Baran, J.; Weres, A.; Mazur, A.; Lewandowski, B. Health behaviours of young adults during the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic—A longitudinal study. BMC Public Heal. 2021, 21, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Frøst, M.B.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C. Reported Changes in Dietary Habits During the COVID-19 Lockdown in the Danish Population: The Danish COVIDiet Study. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 592112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyk-Bębenek, E.; Jagielski, P.; Bolesławska, I.; Jagielska, A.; Nitsch-Osuch, A.; Kawalec, P. Nutrition Behaviors in Polish Adults before and during COVID-19 Lockdown. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Jeyakumar, D.T.; Jayawardena, R.; Chourdakis, M. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on snacking habits, fast-food and alcohol consumption: A systematic review of the evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 21, 00212-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoro, M.; Wakimoto, K.; Otaki, N.; Fukuo, K. Increased Prevalence of Breakfast Skipping in Female College Students in COVID-19. Asia Pac. J. Public Heal. 2021, 33, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Leung, C.W. Food Insecurity and COVID-19: Disparities in Early Effects for US Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.L.; Aronson, B.; Pescosolido, B.A. Pandemic precarity: COVID-19 is exposing and exacerbating inequalities in the American heartland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020685118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrinato, C.V.; Marino, A.; Condé, V.F.; Franco, M.D.C.P.; Stedefeldt, E.; Tomita, L.Y. High prevalence of food insecurity, the adverse impact of COVID-19 in Brazilian favela. Public Heal. Nutr. 2020, 24, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, M.; Beavers, A. The Relationship between Food Security Status and Fruit and Vegetable Intake during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.; Slaughter-Acey, J.; Alexander, T.; Berge, J.; Harnack, L.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Emerging adults’ intersecting experiences of food insecurity, unsafe neighbourhoods and discrimination during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, W.; He, X.; Ma, Y.; Cai, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, R.; Wang, D.; Guo, Y.-F.; et al. The association between subjective impact and the willingness to adopt healthy dietary habits after experiencing the outbreak of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A cross-sectional study in China. Aging 2020, 12, 20968–20981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmester, B.; Pascual, S.; Goldstone, N. Young People’s Changes in Emotional Eating Under Stress: A Natural ex-Periment during the COVID-19 Pandemic [Unpublished Manuscript]; Division of Psychiatry, Imperial College London: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coakley, K.E.; Lardier, D.T.; Le, H.; Wilks, A. Food approach and avoidance appetitive traits in university students: A latent profile analysis. Appetite 2021, 168, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, A.; Patalay, P.; Bann, D. Mental health in relation to changes in sleep, exercise, alcohol and diet during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examination of four UK cohort studies. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiotsa, B.; Naccache, B.; Duval, M.; Rocher, B.; Grall-Bronnec, M. Social Media Use and Body Image Disorders: Association between Frequency of Comparing One’s Own Physical Appearance to That of People Being Followed on Social Media and Body Dissatisfaction and Drive for Thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Schupak-Neuberg, E.; Shaw, H.E.; Stein, R.I. Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: An examination of mediating mechanisms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1994, 103, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A.E.; Camargo, C.A.; Taylor, C.B.; Berkey, C.S.; Colditz, G.A. Relation of peer and media influences to the development of purging behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1999, 153, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Social Media Use during Coronavirus (COVID-19) Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7863/social-media-use-during-coronavirus-covid-19-worldwide/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Vall-Roqué, H.; Andrés, A.; Saldaña, C. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on social network sites use, body image disturbances and self-esteem among adolescent and young women. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 110, 110293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Measurement Tool | Participant Characteristics | Main Findings | Additional Relevant Findings | Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguilar-Martinez et al., 2021 [33], Spain | Cross-sectional (pre-lockdown and during lockdown, 1 cohort) | Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (self-reported; online) | 303 high-school students, 14–18 years, 70% female | 2 × healthy marker increase (fruit * and vegetable * consumption). 3 × unhealthy marker decrease (soft drinks *, sweets and pastries *, and convenience foods). Decrease in regularity of meals *. Increase in snacking between meals. Unit of measurement: increase/decrease/no change pre vs. during pandemic | Reduction in fruit and vegetable consumption, increase in convenience food consumption, decrease in regularly of meals *, and increase in skipping meals * were significantly higher among adolescents from a socioeconomic position perceived to be more disadvantaged *. The highest decrease in the intake of convenience foods was in girls *; the consumption of sweets was the variable that decreased the most in boys *. | High |

| Mastorci et al., 2021 [34], Italy | Cross-sectional (pre-lockdown and during lockdown, 1 cohort) | KIDMED (self-reported; online) | 1289 school children and adolescents (aged 10–14 yrs), 52% female | 1 × healthy marker increase (adherence to the Mediterranean diet ** (Cohen’s d = −0.157 (s)). Unit of measurement: KIDMED score | High | |

| Medrano et al., 2021 [35], Spain | Cross-sectional (pre-lockdown and during lockdown, 1 cohort) | KIDMED (self-reported; online) | 113 school children and adolescents (aged 8–16 yrs), 48% female | 1 × healthy marker increase (adherence to Mediterranean diet *). Unit of measurement: KIDMED score | High | |

| Munasinghe et al., 2020 [36], Australia | Cross-sectional (1 cohort followed up weekly over 22 weeks, a period spanning before and during lockdown) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (online, self-reported) | 582 adolescents (aged 13–19 yrs) from the general population, 61% females | 1 × unhealthy marker decrease (fast food consumption *, Cohen’s d = 0.350 (m)). Unit of measurement: servings per day | High | |

| James et al., 2021 [37], Wales | Cross-sectional (pre-lockdown and during lockdown, separate cohorts) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (self-reported, online) | 2218 (1150 pre-pandemic; 1068 pandemic) school children (aged 8–11 yrs), 51% females | 2 × unhealthy marker decrease (takeaways *, fizzy drink consumption). 1 × unhealthy marker increase (sugary snacks *). 1 × healthy eating marker decrease (fruit/veg consumption). Increase in frequency of breakfast consumption *. Unit of measurement: frequency of consumption per week | Those who had free school means had significantly lower fruit and veg consumption * and lower sugary snack consumption. | High |

| Kim et al., 2021 [38], Korea | Cross sectional (pre-lockdown and during lockdown, separate cohorts) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (self-reported, online) | 105,600 middle- and high-school adolescents (53,461 pre-pandemic; 52,139 pandemic), aged 12–18 yrs, 52% female | 1 × healthy marker decrease (fruit **) 3 × unhealthy marker decrease (fast food **, soda **, sweet drinks **). Higher frequency of eating breakfast **. Unit of measurement: amount per week | Reporting subjective body shape image as obese was lower in the 2019 group than in the 2020 group **. BMI was slightly though significantly higher in the 2020 group (21.3 vs. 21.5) ** | High |

| Luszczki et al., 2021 [39], Poland | Cross-sectional (pre-lockdown and during lockdown, separate cohorts) | Modified Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ-6) (parent reported for children, self-reported for adolescents; online) | 1017 (376 pre-pandemic group; 641 during lockdown group) school children (ages 6–12 yrs) and adolescents (aged 13–15 yrs), 51% females | 4 × healthy marker decrease (legumes ** (Cohen’s d = 0.291 (s)), fish * (Cohen’s d = 0.081 (t)), raw veg, fresh fruits). 2 × unhealthy marker decrease (carbonated sugar-sweetened drinks, fast foods ** (Cohen’s d = 0.262 (s)). Decreased snacking * Unit of measurement: frequency of consumption per day or week | Average | |

| Al Hoirani et al., 2021 [40], Jordan | Cross-sectional (current (during lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Food Frequency Questionnaire (parent reported for children, self-reported for adolescents; online) | 447 children (6–12 yrs, 51%) and adolescents (13–17 yrs, 49%) from the general population, 52% female | 3 × healthy marker increase (cooked veg for children * (Cohen’s d= −0.08 (t)) and adolescents ** (Cohen’s d = −0.14 (s)), raw veg for children * (Cohen’s d = −0.14 (s)) and adolescents * (Cohen’s d = −0.11 (s)), total fruits for children ** (Cohen’s d = −0.13 (s)) and adolescents ** (Cohen’s d = −0.16 (s)). 7 × unhealthy markers increase (carbonated drinks for children ** (Cohen’s d = −0.15 (s)) and adolescents * (Cohen’s d −0.13 (s)), fries for children * (Cohen’s d = −0.14 (s)) and adolescents ** (Cohen’s d = −0.19(s)), pizza * (Cohen’s d = -0.1(s)) and potato chips ** (Cohen’s d = −0.21(s)) for adolescents, sugar for children * (Cohen’s d = −0.1(s) and adolescents ** (Cohen’s d = −0.19 (s), ice cream for children ** (Cohen’s d= −0.2 (s)) and adolescents ** (Cohen’s d = −0.18 (s)), cake for children ** (Cohen’s d = −0.18 (s), trend in cake for adolescents. Unit of measurement: servings per day | Increase in BMI for age Z-score **, decrease in thinness and severe thinness ** | Low |

| Androutsos et al., 2021 [41], Greece | Cross-sectional (current (during lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (parent-reported; online) | 397 adolescents (12–18 yrs) from the general population, 49% females | 2 × healthy marker increase (fruit ** Cohen’s d = −0.215 (s), vegetables ** Cohen’s d = −0.093 (t)). 3 × unhealthy marker increase (prepacked juices and sodas, salty snacks, sweets ** Cohen’s d = −0.333 (m)). 1 × unhealthy marker decrease (fast food ** (Cohen’s d = 0.045 (t)). Increased snack frequency ** (Cohen’s d = −0.597 (l)). Increased breakfast consumption frequency ** (Cohen’s d = −0.267 (s)). Unit of measurement: servings per day | Multiple regression analysis showed that body weight increase was associated with increased consumption of breakfast, salty snacks, and total snacks, and with decreased physical activity. | High |

| Horikawa et al., 2021 [42], Japan | Cross-sectional (current (during lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (parent-reported; paper postal questionnaire) | 1111 children and adolescents (10–14 yrs) from the general population, 51% females | 2 × healthy marker decrease (fruit ** and veg **). Decreased population of ‘well-balanced dietary intake’ during lockdown **. Unit of measurement: consumption at least twice per day over one month. | The lower the income group, the greater the rate of decrease in ‘well-balanced dietary intake’ during lockdown. ** | High |

| Kolata et al., 2021 [43], Poland | Cross-sectional (current (during lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (self-reported; online) | 1334 school children and adolescents (10–16 yrs), 53% females | 2 × healthy marker increase (fruit ** and veg **). No significant change in markers of unhealthy eating (fast food, fried potato consumption). Unit of measurement: portions per day. | High | |

| Konstantinou et al., 2021 [44], Cyprus | Cross-sectional (current (during lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Bespoke food frequency questionnaire (parent-reported; online) | 1509 school children and adolescents (aged 5–14 yrs), 48% females | 1 × healthy marker increase (consumption of fish **). 1 × unhealthy marker increase (consumption of sugary foods **). 1 × unhealthy marker decrease (consumption of ready-made foods). No change for fruit, vegetable, or legume consumption. Increased daily consumption of breakfast *. Unit of measurement: number of days consumed per week. | High | |

| Muzi et al., 2021 [45], Italy | Cross sectional (one point during lockdown, compared with eating data from one pre-lockdown study) | Binge Eating Scale (self-reported; online) | 62 adolescents aged 12–17 yrs from the general population; 63% females | No difference in binge eating scale outcomes. Unit of measurement: Binge Eating Scale score | Pandemic adolescents exhibited more problematic social media usage than their pre-pandemic peers (p < 0.001); more problematic social media usage was correlated with a higher total score of emotional-behavioural symptoms (p < 0.05) (p < 0.05) and more binge-eating attitudes (p < 0.05) (p < 0.05). The role of problematic social media usage was explored as a potential predictor of more total and externalizing problems and binge-eating attitudes, but no predictive model was statistically significant, all p < 0.076 | Average |

| Radwan et al., 2021 [46], Palestine | Cross-sectional (current (during lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (parent-reported for <11 yrs, self-reported for 12 + yrs; online) | 6398 school children and adolescents (aged 6–18 yrs, 88% 10–14 yrs), 80% females | 5 × healthy marker increase (overall healthy food rating **, higher median ‘food quality score’ **, increase in students’ rating of their healthy food consumption as very good/excellent ** increased fruit consumption 2+/day **, more home-cooked meals **, and decrease in 1 other (lower veg consumption 2+/day **). 3 × unhealthy marker decrease (decreased fast food consumption **, decreased consumption of sodas/sweet tea 3+/day **, decreased desserts/sweets 4+ times/week **). Decreased snacking **. Decrease in food quantity ** Units of measurement: number of days consumed on per week | Boys had higher food quality scores during the pandemic **, whereas girls had higher pre-pandemic scores in food quality. Students aged 6–9 years exhibited a higher food quality score during the COVID-19 period than before the COVID-19 period **, whereas students aged 10–14 ** and 15–18 ** years attained a lower score during the COVID-19 period. Students aged 6–9 and 15–18 years had higher food quantity scores during the COVID-19 period **, but students aged 10–14 years had a lower score. Decrease in the proportion of students whose families bought groceries every day **. Increase in students who agreed or strongly agreed with the idea of choosing food according to calorie content and healthy properties when they buy **. Marked increase in students reporting fears about food hygiene from outside during the pandemic **. | High |

| Segre et al., 2021 [47], Italy | Cross-sectional (one time point during data, change data) | Bespoke (self- and parent-reported, video interview) | 82 school children and adolescents (aged 6–14 yrs), 54.9 % primary school, 45.1 % middle school, 46% females | A significant proportion of children reported a perceived change in their eating habits *. Non-significant trend towards children reporting eating more during the pandemic, with a non-significant increase in the consumption of junk food, snacks, and sweets. Units of measurement: increase/decrease /no change pre vs. during pandemic | ‘Changed eating behaviours’ were more significant in primary school children * compared with middle school children. Anxiety levels were not found to be significantly associated with changes in eating behaviours. Higher frequency of mood symptoms was associated with changes in dietary habits *. | High |

| Yu et al., 2021 [48], China | Cross-sectional (current (after lockdown) and retrospective (pre-lockdown) estimates) | Bespoke questionnaire including food frequency data (self-reported; online) | 2824 high school students, 72% females | 3 × healthy eating marker increase (fish * Cohen’s d = −0.077 (t), fresh veg * Cohen’s d = −0.045 (t), preserved veg * Cohen’s d = −0.056 (t)). Units of measurement: frequency of consumption per week | Low |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brakspear, L.; Boules, D.; Nicholls, D.; Burmester, V. The Impact of COVID-19-Related Living Restrictions on Eating Behaviours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173657

Brakspear L, Boules D, Nicholls D, Burmester V. The Impact of COVID-19-Related Living Restrictions on Eating Behaviours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(17):3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173657

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrakspear, Lucy, Daniella Boules, Dasha Nicholls, and Victoria Burmester. 2022. "The Impact of COVID-19-Related Living Restrictions on Eating Behaviours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 14, no. 17: 3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173657

APA StyleBrakspear, L., Boules, D., Nicholls, D., & Burmester, V. (2022). The Impact of COVID-19-Related Living Restrictions on Eating Behaviours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 14(17), 3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173657