Maternal Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods-Rich Diet and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Appraisal of Methodological Quality

2.6. Summary Measures and Data Analysis

2.7. Quality of Meta-Evidence

3. Results

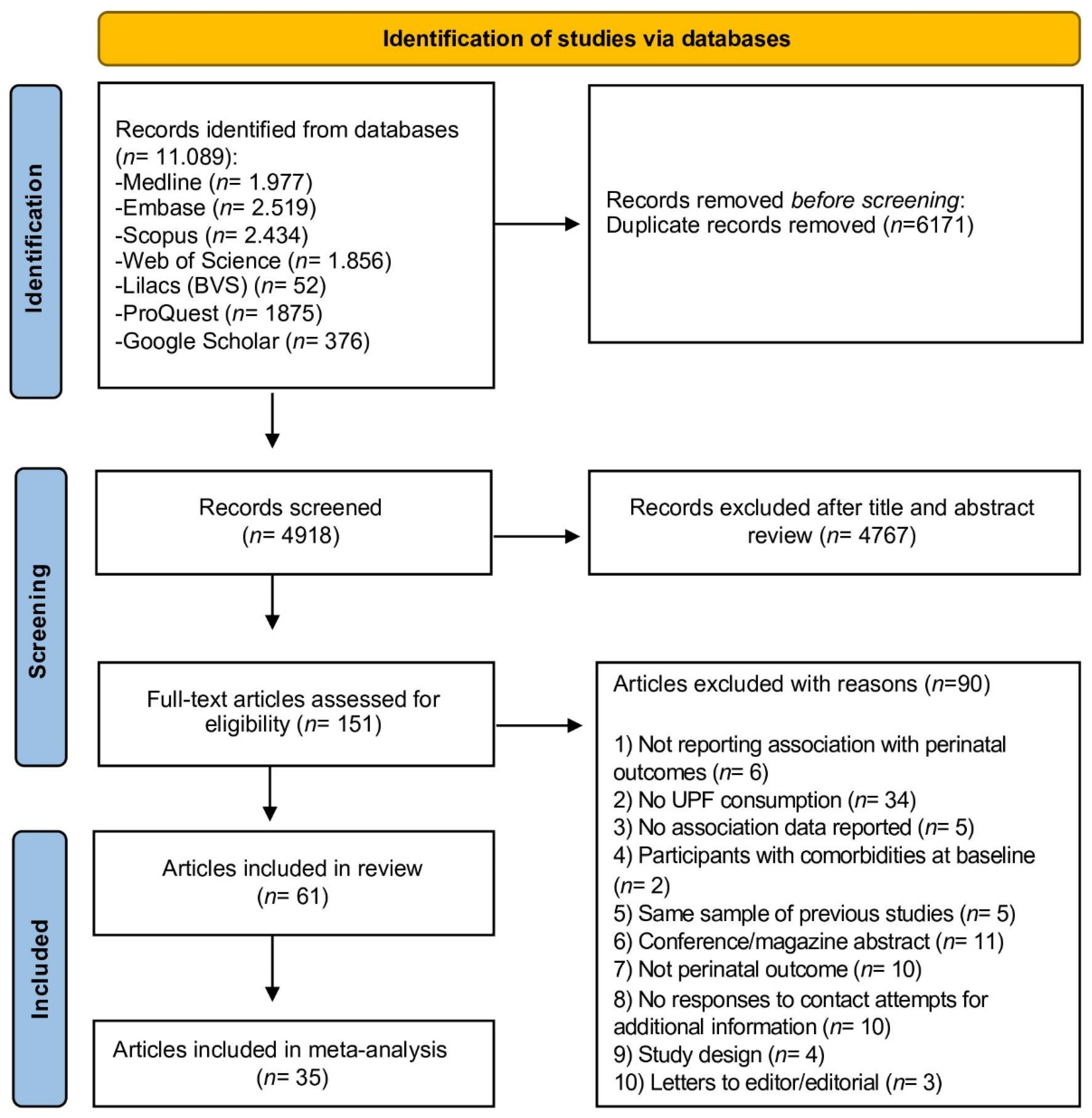

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Results of Individual Studies

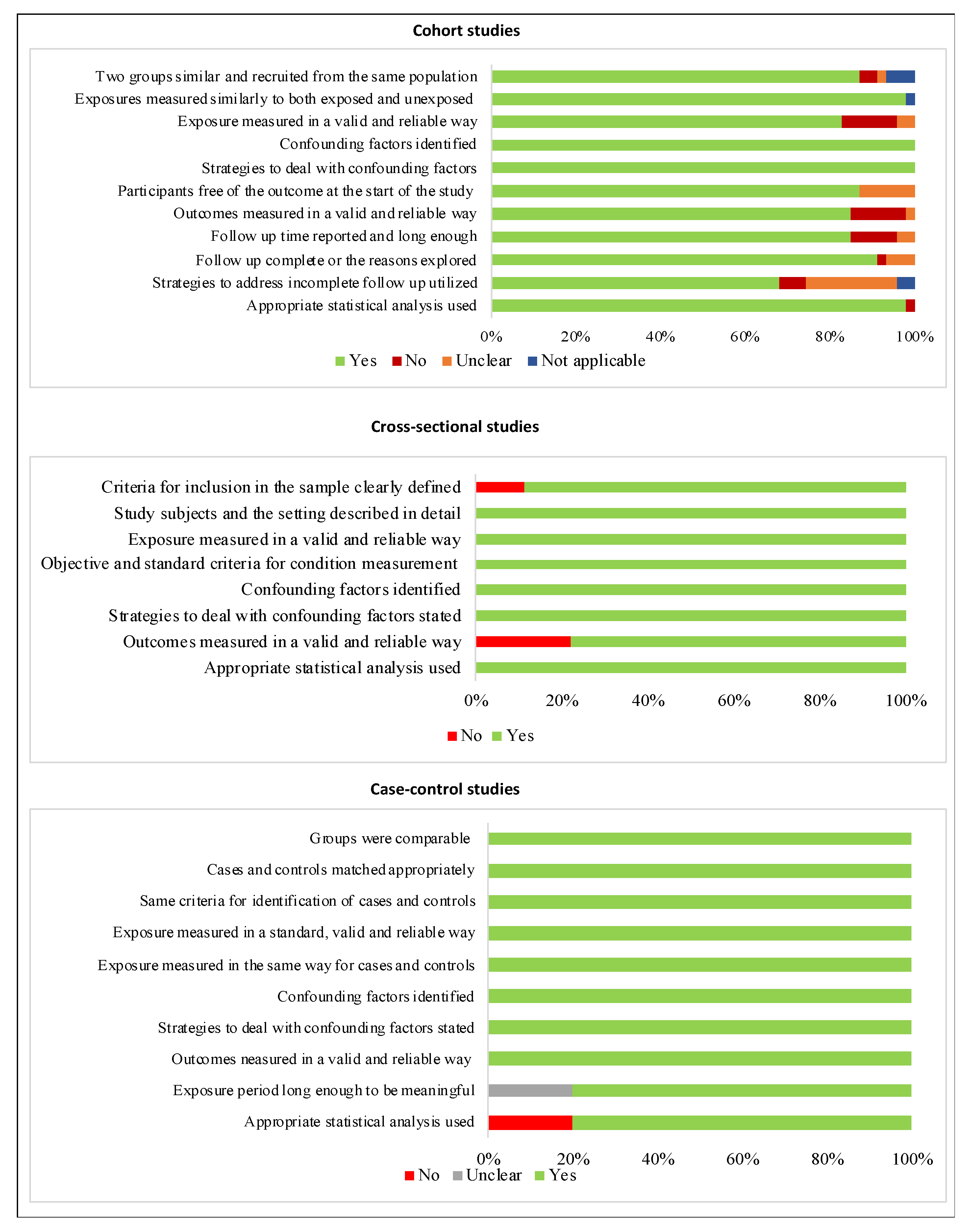

3.4. Risk of Bias within Individual Studies

3.5. Meta-Analysis of Maternal UPF-Rich Diet Consumption and Maternal Outcomes

3.5.1. Gestational Weight Gain

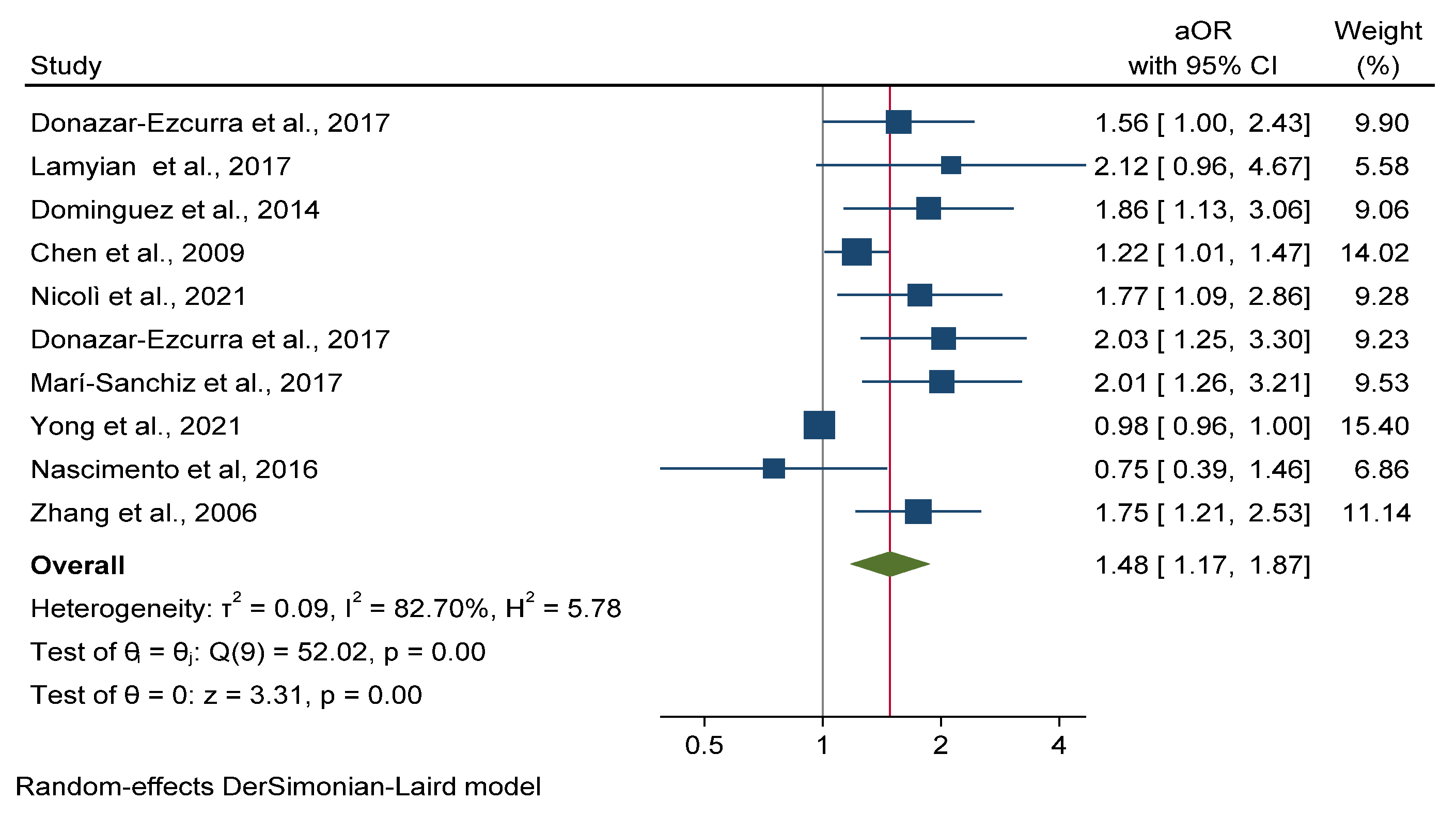

3.5.2. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

3.5.3. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

3.6. Meta-Analysis of Maternal UPF-Rich Diet Consumption and Neonatal Outcomes

3.6.1. Low Birth Weight

3.6.2. Large for Gestational Age

3.6.3. Preterm Birth

3.7. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soma-Pillay, P.; Nelson-Piercy, C.; Tolppanen, H.; Mebazaa, A. Physiological Changes in Pregnancy. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016, 27, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Good Maternal Nutrition: The Best Start in Life; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; ISBN 9789289051545. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, E.L.S.S.; de Lima Macêna, M.; Bueno, N.B.; de Oliveira, A.C.M.; Mello, C.S. Premature Birth, Low Birth Weight, Small for Gestational Age and Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases in Adult Life: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 149, 105154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohatgi, K.W.; Tinius, R.A.; Cade, W.T.; Steele, E.M.; Cahill, A.G.; Parra, D.C. Relationships between Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods, Gestational Weight Gain and Neonatal Outcomes in a Sample of US Pregnant Women. PeerJ 2017, 2017, e4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deierlein, A.L.; Ghassabian, A.; Kahn, L.G.; Afanasyeva, Y.; Mehta-Lee, S.S.; Brubaker, S.G.; Trasande, L. Dietary Quality and Sociodemographic and Health Behavior Characteristics Among Pregnant Women Participating in the New York University Children’s Health and Environment Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 639425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojhani, A.; Ouyang, P.; Gullon-Rivera, A.; Dale, T.M. Dietary Quality of Pregnant Women Participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, A.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Craig, W.; Fresán, U.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Pre-Gestational Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Risk of Gestational Diabetes in a Mediterranean Cohort. The SUN Project. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA Food Classification and the Trouble with Ultra-Processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; Castro, I.R.R.D.; Cannon, G. A New Classification of Foods Based on the Extent and Purpose of Their Processing. Cad. Saúde Pública 2010, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods: What They Are and How to Identify Them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordain, L.; Eaton, S.B.; Sebastian, A.; Mann, N.; Lindeberg, S.; Watkins, B.A.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Brand-Miller, J. Origins and Evolution of the Western Diet: Health Implications for the 21st Century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-Processed Products Are Becoming Dominant in the Global Food System. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juul, F.; Parekh, N.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Monteiro, C.A.; Chang, V.W. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption among US Adults from 2001 to 2018. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, F.; Louzada, M.L.D.C.; Martinez Steele, E.; De Rezende, L.F.M.; Millett, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-Processed Foods and Excessive Free Sugar Intake in the UK: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Lawrence, M.; Costa Louzada, M.L.; Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131701-3. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P.; Friel, S. Food Systems Transformations, Ultra-Processed Food Markets and the Nutrition Transition in Asia. Glob. Health 2016, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martini, D.; Godos, J.; Bonaccio, M.; Vitaglione, P.; Grosso, G. Ultra-Processed Foods and Nutritional Dietary Profile: A Meta-Analysis of Nationally Representative Samples. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, C.D.B.; Malta, M.B.; Benício, M.H.D.A.; Carvalhaes, M.A.D.B.L. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods in the Third Gestational Trimester and Increased Weight Gain: A Brazilian Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 3304–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamyian, M.; Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Mirmiran, P.; Banaem, L.M.; Goshtasebi, A.; Azizi, F. Pre-Pregnancy Fast Food Consumption Is Associated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus among Tehranian Women. Nutrients 2017, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ikem, E.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Birgisdóttir, B.E.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Olsen, S.F.; Maslova, E. Dietary Patterns and the Risk of Pregnancy-Associated Hypertension in the Danish National Birth Cohort: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 126, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amezcua-Prieto, C.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Cano-Ibáñez, N.; Olmedo-Requena, R.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M. Types of Carbohydrates Intake during Pregnancy and Frequency of a Small for Gestational Age Newborn: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grieger, J.A.; Grzeskowiak, L.E.; Clifton, V.L. Preconception Dietary Patterns in Human Pregnancies Are Associated with Preterm Delivery. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartorelli, D.S.; Crivellenti, L.C.; Zuccolotto, D.C.C.; Franco, L.J. Relationship between Minimally and Ultra-Processed Food Intake during Pregnancy with Obesity and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Cad. Saúde Publica 2019, 35, e00049318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, C.; Souza, R.C.V.e.; Santos, L.C. Dos Influência Do Consumo de Alimentos Ultraprocessados Durante a Gestação Nas Medidas Antropométricas Do Bebê, Do Nascimento Ao Primeiro Ano de Vida: Uma Revisão Sistemática (The Influence of the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods During Pregnancy on Anthropometric Measurements of the Baby, From Birth to the First Year of Life: A Systematic Review). Rev. Bras. Saúde Matern. Infant. 2021, 21, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kinshella, M.L.W.; Omar, S.; Scherbinsky, K.; Vidler, M.; Magee, L.A.; Von Dadelszen, P.; Moore, S.E.; Elango, R. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Pregnancy Hypertension in Low—A Nd Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2387–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.R.; Chen, L.W.; Lai, J.S.; Wong, C.H.; Neelakantan, N.; Van Dam, R.M.; Chong, M.F.F. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Birth Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira, P.G.; De Sousa, J.M.; Assunção, D.G.F.; de Araujo, E.K.S.; Bezerra, D.S.; dos Dametto, J.F.S.; da Ribeiro, K.D.S. Impacts of Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Maternal-Child Health: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 821657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabin, B.; Baschat, A.A. Pregnancy: An Underutilized Window of Opportunity to Improve Long-Term Maternal and Infant Health—An Appeal for Continuous Family Care and Interdisciplinary Communication. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Zhang, J.; Yu, K.F. Special Communication What’s the Relative Risk? A Method of Correcting the Odds Ratio in Cohort Studies of Common Outcomes. JAMA 1998, 280, 1690–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G. Analysing Data and Undertaking Meta-Analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. Quality of Evidence. In GRADE Handbook; Schünemann, H., Brożek, J., Guyatt, G., Oxman, A., Eds.; GRADE Working Group: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ding, Y.; Shi, L.; Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Mo, Y. Dietary Patterns and Gestational Hypertension in Nulliparous Pregnant Chinese Women: A CONSORT Report. Medicine 2020, 99, e20186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, L.; Radwan, H.; Hashim, M.; Hasan, H.; Obaid, R.S.; Al Ghazal, H.; Al Hilali, M.; Rayess, R.; Mohamed, H.J.J.; Hamadeh, R.; et al. Dietary Patterns and Their Associations with Gestational Weight Gain in the United Arab Emirates: Results from the MISC Cohort. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abbasi, R.; Bakhshimoghaddam, F.; Alizadeh, M. Major Dietary Patterns in Relation to Preeclampsia among Iranian Pregnant Women: A Case–Control Study. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2019, 34, 3529–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, M.; Shahzeidi, M.; Nadjarzadeh, A.; Hashemi Yusefabad, H.; Mansoori, A. The Relationship between Pre-Pregnancy Dietary Patterns Adherence and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Iran: A Case–Control Study. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajianfar, H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Feizi, A.; Shahshahan, Z.; Azadbakht, L. The Association between Major Dietary Patterns and Pregnancy-Related Complications. Arch. Iran. Med. 2018, 21, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Hajianfar, H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Feizi, A.; Shahshahan, Z.; Azadbakht, L. Major Maternal Dietary Patterns during Early Pregnancy and Their Association with Neonatal Anthropometric Measurement. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4692193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sedaghat, F.; Akhoondan, M.; Ehteshami, M.; Aghamohammadi, V.; Ghanei, N.; Mirmiran, P.; Rashidkhani, B. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Gestational Diabetes Risk: A Case-Control Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 5173926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angali, K.A.; Shahri, P.; Borazjani, F. Maternal Dietary Pattern in Early Pregnancy Is Associated with Gestational Weight Gain and Hyperglycemia: A Cohort Study in South West of Iran. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1711–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, S.L.; Marhazlina, M.; Jan, J.M.H. Association between Maternal Food Group Intake and Birth Size. Sains Malays. 2013, 42, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Okubo, H.; Miyake, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Murakami, K.; Hirota, Y.; Osaka, M.; Kanzaki, H.; Kitada, M.; Horikoshi, Y.; et al. Maternal Dietary Patterns in Pregnancy and Fetal Growth in Japan: The Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zareei, S.; Homayounfar, R.; Naghizadeh, M.M.; Ehrampoush, E.; Amiri, Z.; Rahimi, M.; Tahamtani, L. Dietary Pattern in Patients with Preeclampsia in Fasa, Iran. Shiraz E-Medical J. 2019, 20, e86959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ker, C.R.; Wu, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Wang, S.H.; Chan, T.F. Increased Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Use Tendency in Pregnancy Positively Associates with Peripartum Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scores. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, F.; Mi, B.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Pei, L. Geographical Variations in Maternal Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy Associated with Birth Weight in Shaanxi Province, Northwestern China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamada, H.; Ebara, T.; Matsuki, T.; Kato, S.; Sato, H.; Ito, Y.; Saitoh, S.; Kamijima, M.; Sugiura-Ogasawara, M.; Group, J.E. and C.S. Ready-Meal Consumption During Pregnancy Is a Risk Factor for Stillbirth: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 14, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.Y.; Shariff, Z.M.; Yusof, B.N.M.; Rejali, Z.; Tee, Y.Y.S.; Bindels, J.; van der Beek, E.M. Beverage Intake and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The SECOST. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitku, A.A.; Zewotir, T.; North, D.; Jeena, P.; Naidoo, R.N. The Differential Effect of Maternal Dietary Patterns on Quantiles of Birthweight. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrottesley, S.V.; Pisa, P.T.; Norris, S.A. The Influence of Maternal Dietary Patterns on Body Mass Index and Gestational Weight Gain in Urban Black South African Women. Nutrients 2017, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barbosa, J.M.A.; da Silva, A.A.M.; Kac, G.; Simões, V.M.F.; Bettiol, H.; Cavalli, R.C.; Barbieri, M.A.; Ribeiro, C.C.C. Is Soft Drink Consumption Associated with Gestational Hypertension? Results from the Brisa Cohort. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, e10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancira-Moreno, M.; O’Neill, M.S.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.Á.; Batis, C.; Rodríguez Ramírez, S.; Sánchez, B.N.; Castillo-Castrejón, M.; Vadillo-Ortega, F. Dietary Patterns and Diet Quality during Pregnancy and Low Birthweight: The PRINCESA Cohort. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e12972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alves-Santos, N.H.; Cocate, P.G.; Benaim, C.; Farias, D.R.; Emmett, P.M.; Kac, G. Prepregnancy Dietary Patterns and Their Association with Perinatal Outcomes: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Siega-Riz, A.M. Maternal Dietary Patterns during the Second Trimester Are Associated with Preterm Birth. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Hu, F.B.; Yeung, E.; Willett, W.; Zhang, C. Prospective Study of Pre-Gravid Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2236–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Schulze, M.B.; Solomon, C.G.; Hu, F.B. A Prospective Study of Dietary Patterns, Meat Intake and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2604–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirko, K.A.; Comstock, S.S.; Strakovsky, R.S.; Kerver, J.M. Diet during Pregnancy and Gestational Weight Gain in a Michigan Pregnancy Cohort. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.L.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Robinson, W.R.; Daniels, J.L.; Perrin, E.M.; Stuebe, A.M. Maternal Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy Are Associated with Child Growth in the First 3 Years of Life. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2281–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, J.A.; Hoffman, D.J.; Castro, T.G.; Saldiva, S.R.D.M.; Francisco, R.P.V.; Vieira, S.E.; Marchioni, D.M. Pre-Pregnancy Dietary Pattern Is Associated with Newborn Size: Results from ProcriAr Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccolotto, D.C.C.; Crivellenti, L.C.; Franco, L.J.; Sarotelli, D.S. Padrões Alimentares de Gestantes, Excesso de Peso Materno e Diabetes Gestacional (Dietary Patterns of Pregnant Women, Excessive Maternal Weight and Gestational Diabetes). Rev. Saúde Publica 2019, 53, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.R.; Alves, L.V.; Fonseca, C.L.; Figueiroa, J.N.; Alves, J.G. Dietary Patterns and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Low Income Pregnant Women Population in Brazil—A Cohort Study. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2016, 66, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- De Coelho, N.L.P.; Cunha, D.B.; Esteves, A.P.P.; de Lacerda, E.M.A.; Filha, M.M.T. Dietary Patterns in Pregnancy and Birth Weight. Rev. Saúde Publica 2015, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marquez, B.V.Y. Association between Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Both Gestational Weight Gain and Gestational Diabetes; The University of Texas School of Public Health: Dallas, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, B.; Azeredo, V.; Silva, A. Relationship between Food Consumption of Pregnant Women and Birth Weight of Newborns. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2020, 47, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Günther, J.; Hoffmann, J.; Spies, M.; Meyer, D.; Kunath, J.; Stecher, L.; Rosenfeld, E.; Kick, L.; Rauh, K.; Hauner, H. Associations between the Prenatal Diet and Neonatal Outcomes—A Secondary Analysis of the Cluster-Randomised Gelis Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Agodi, A. Maternal Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index and Gestational Weight Gain: Results from the “Mamma & Bambino” Cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Englund-Ögge, L.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Juodakis, J.; Haugen, M.; Meltzer, H.M.; Jacobsson, B.; Sengpiel, V. Associations between Maternal Dietary Patterns and Infant Birth Weight, Small and Large for Gestational Age in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí-Sanchis, A.; Díaz-Jurado, G.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Association between Pre-Pregnancy Consumption of Meat, Iron Intake, and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes: The SUN Project. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.B.; Lund, M.; Corn, G.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Øyen, N.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Olsen, S.F.; Melbye, M. Dietary Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load during Pregnancy and Offspring Risk of Congenital Heart Defects: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donazar-Ezcurra, M.; Lopez-Del Burgo, C.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; De Irala, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Pre-Pregnancy Adherences to Empirically Derived Dietary Patterns and Gestational Diabetes Risk in a Mediterranean Cohort: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 118, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donazar-Ezcurra, M.; Lopez-del Burgo, C.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; de Irala, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Soft Drink Consumption and Gestational Diabetes Risk in the SUN Project. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 37, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundt, J.H.; Eide, G.E.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Haugen, M.; Markestad, T. Is Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drinks during Pregnancy Associated with Birth Weight? Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 13, e12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Gea, A.; Barbagallo, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Fast Food Consumption and Gestational Diabetes Incidence in the SUN Project. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgen, I.; Aamodt, G.; Harsem, N.; Haugen, M.; Meltzer, H.M.; Brantsæter, A.L. Maternal Sugar Consumption and Risk of Preeclampsia in Nulliparous Norwegian Women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brantsæter, A.L.; Haugen, M.; Samuelsen, S.O.; Torjusen, H.; Trogstad, L.; Alexander, J.; Magnus, P.; Meltzer, H.M. A Dietary Pattern Characterized by High Intake of Vegetables, Fruits, and Vegetable Oils Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Preeclampsia in Nulliparous Pregnant Norwegian Women. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uusitalo, U.; Arkkola, T.; Ovaskainen, M.L.; Kronberg-Kippilä, C.; Kenward, M.G.; Veijola, R.; Simell, O.; Knip, M.; Virtanen, S.M. Unhealthy Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Weight Gain during Pregnancy among Finnish Women. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 2392–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nicolì, F.; Prete, A.; Citro, F.; Bertolotto, A.; Aragona, M.; de Gennaro, G.; Del Prato, S.; Bianchi, C. Use of Non-Nutritive-Sweetened Soft Drink and Risk of Gestational Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 178, 108943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, M.T.G.; Magnus, P.; Leirgul, E.; Holmstrøm, H.; Gjessing, H.K.; Brodwall, K.; Haugen, M.; Stoltenberg, C.; Øyen, N. Intake of Sucrose-Sweetened Soft Beverages during Pregnancy and Risk of Congenital Heart Defects (CHD) in Offspring: A Norwegian Pregnancy Cohort Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garay, S.M.; Savory, K.A.; Sumption, L.; Penketh, R.; Janssen, A.B.; John, R.M. The Grown in Wales Study: Examining Dietary Patterns, Custom Birthweight Centiles and the Risk of Delivering a Small-for-Gestational Age (SGA) Infant. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tielemans, M.J.; Erler, N.S.; Leermakers, E.T.M.; van den Broek, M.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Franco, O.H. A Priori and a Posteriori Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy and Gestational Weight Gain: The Generation R Study. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9383–9399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Olsen, S.F.; Mendola, P.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Rawal, S.; Hinkle, S.N.; Yeung, E.H.; Chavarro, J.E.; Grunnet, L.G.; Granström, C.; et al. Maternal Consumption of Artificially Sweetened Beverages during Pregnancy, and Offspring Growth through 7 Years of Age: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmussen, M.A.; Maslova, E.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Olsen, S.F. Characterization of Dietary Patterns in the Danish National Birth Cohort in Relation to Preterm Birth. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bärebring, L.; Brembeck, P.; Löf, M.; Brekke, H.K.; Winkvist, A.; Augustin, H. Food Intake and Gestational Weight Gain in Swedish Women. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Englund-Ögge, L.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Sengpiel, V.; Haugen, M.; Birgisdottir, B.E.; Myhre, R.; Meltzer, H.M.; Jacobsson, B. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Preterm Delivery: Results from Large Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2014, 348, g1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mikeš, O.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Knutsen, H.K.; Torheim, L.E.; Bienertová Vašků, J.; Pruša, T.; Čupr, P.; Janák, K.; Dušek, L.; Klánová, J. Dietary Patterns and Birth Outcomes in the ELSPAC Pregnancy Cohort. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 76, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.M.; Simpson, J.M.; Rissel, C.; Baur, L.A. Maternal “Junk Food” Diet During Pregnancy as a Predictor of High Birthweight: Findings from the Healthy Beginnings Trial. Birth 2013, 40, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, R.; Hill, B.; Jacka, F.N.; O’Neil, A.; Skouteris, H. Antenatal Dietary Patterns and Depressive Symptoms during Pregnancy and Early Post-Partum. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.B.; Lobo, C.V.; do Carmo, A.S.; Souza, R.C.V.E.; Dos Santos, L.C. Dietary Patterns During Pregnancy and Their Association with Gestational Weight Gain and Anthropometric Measurements at Birth. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, C.O.; de Souza, J. Diet during Pregnancy: Ultra-Processed Foods and the Inflammatory Potential of Diet. Nutrition 2022, 97, 111603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Dinu, M.; Madarena, M.P.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Sofi, F. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, J.; Nie, J. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, S.S.; Sousa, L.C.M.; de Oliveira Silva, D.F.; Pimentel, J.B.; de Evangelista, K.C.M.S.; de Lyra, C.O.; Lopes, M.M.G.D.; Lima, S.C.V.C. A Systematic Review on Processed/Ultra-Processed Foods and Arterial Hypertension in Adults and Older People. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassani Zadeh, S.; Boffetta, P.; Hosseinzadeh, M. Dietary Patterns and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, W.; Zeng, M.; Jiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xue, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Qin, F.; He, Z.; Chen, J. Western Dietary Patterns, Foods, and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibret, K.T.; Chojenta, C.; Gresham, E.; Tegegne, T.K.; Loxton, D. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Risk of Adverse Pregnancy (Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus) and Birth (Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight) Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, S.; Soltani, S.; De Souza, R.J.; Forbes, S.C.; Toupchian, O.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. Associations between Maternal Dietary Patterns and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traore, S.S.; Bo, Y.; Amoah, A.N.; Khatun, P.; Kou, G.; Hu, Y.; Lyu, Q. A Meta-Analysis of Maternal Dietary Patterns and Preeclampsia. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2021, 40, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Lemoine, E.; Granger, J.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology, Challenges, and Perspectives. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1094–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garovic, V.D.; Dechend, R.; Easterling, T.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Baird, S.M.M.; Magee, L.A.; Rana, S.; Vermunt, J.V.; August, P. Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Blood Pressure Goals, and Pharmacotherapy: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2022, 79, E21–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, B.; Liu, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Fu, J.; Ling, Q.; Xiao, C.; et al. Gestational Systolic Blood Pressure Trajectories and Risk of Adverse Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes in Chinese Women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diemert, A.; Lezius, S.; Pagenkemper, M.; Hansen, G.; Drozdowska, A.; Hecher, K.; Arck, P.; Zyriax, B.C. Maternal Nutrition, Inadequate Gestational Weight Gain and Birth Weight: Results from a Prospective Birth Cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishra, K.G.; Bhatia, V.; Nayak, R. Maternal Nutrition and Inadequate Gestational Weight Gain in Relation to Birth Weight: Results from a Prospective Cohort Study in India. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2020, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagiou, P.; Tamimi, R.M.; Mucci, L.A.; Adami, H.-O.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Trichopoulos, D. Diet during Pregnancy in Relation to Maternal Weight Gain and Birth Size. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dude, A.M.; Grobman, W.; Haas, D.; Mercer, B.M.; Parry, S.; Silver, R.M.; Wapner, R.; Wing, D.; Saade, G.; Reddy, U.; et al. Gestational Weight Gain and Pregnancy Outcomes among Nulliparous Women. Am. J. Perinatol. 2021, 38, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Effects of Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index and Gestational Weight Gain on Maternal and Infant Complications. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbu, R.E.; Fouedjio, H.J.; Tabot, M.; Fouelifack, F.Y.; Tumasang, F.N.; Tonye, R.N.; Leke, R.J.I. Effects of Gestational Weight Gain on the Outcome of Labor at the Yaounde Central Hospital Maternity, Cameroon. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 3, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashley-Martin, J.; Woolcott, C. Gestational Weight Gain and Postpartum Weight Retention in a Cohort of Nova Scotian Women. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widen, E.M.; Whyatt, R.M.; Hoepner, L.A.; Ramirez-Carvey, J.; Oberfield, S.E.; Hassoun, A.; Perera, F.P.; Gallagher, D.; Rundle, A.G. Excessive Gestational Weight Gain Is Associated with Long-Term Body Fat and Weight Retention at 7 y Postpartum in African American and Dominican Mothers with Underweight, Normal, and Overweight Prepregnancy BMI. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shin, D.; Lee, K.W.; Song, W.O. Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy Are Associated with Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9369–9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silva, C.F.M.; Saunders, C.; Peres, W.; Folino, B.; Kamel, T.; dos Santos, M.S.; Padilha, P. Effect of Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption on Glycemic Control and Gestational Weight Gain in Pregnant with Pregestational Diabetes Mellitus Using Carbohydrate Counting. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-T.; Chen, S.-F.; Lo, L.-M.; Li, M.-J.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Hung, T.-H. The Association Between Maternal Oxidative Stress at Mid-Gestation and Subsequent Pregnancy Complications. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 19, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Ha, E.-H.; Park, H.; Ha, M.; Lee, S.-H.; Hong, Y.-C.; Chang, N. Fruit and Vegetable Intake Influences the Association between Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and a Marker of Oxidative Stress in Pregnant Women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pistollato, F.; Sumalla Cano, S.; Elio, I.; Masias Vergara, M.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Plant-Based and Plant-Rich Diet Patterns during Gestation: Beneficial Effects and Possible Shortcomings. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. Low Birth Weight. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/low-birth-weight (accessed on 4 March 2022).

| Author, Year Country | Study Design | Age (Years) | GW (Range or Mean) | Sample n = | Exposure | Outcome | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbasi et al., 2019 Iran [37] | Case-control | case: 24 ± 8 control: 26 ± 6 | >20 weeks | case: 170 control: 340 | WDP (red and processed meat, fried potatoes, pickles, sweets, pizza) | Risk of preeclampsia | The Western dietary pattern associated with preeclampsia: OR: 5.99; 95% CI: 3.414, 10.53; p < 0.001) |

| Alves-Santos et al., 2019 Brazil [54] | Prospective Cohort | 26.7 ± 5.5 | 5–13 weeks | 193 | Fast foods and candies (fast food and snacks; cakes, cookies, or crackers; and candies or desserts) | LGA Birth Length (BL) | Fast food and candies dietary pattern associated with LGA newborn: OR: 4.38; 95% CI: 1.32, 14.48 Fast food and candies dietary pattern associated with the newborn with BL > 90th percentile: OR: 4.81; 95% CI: 1.77, 13.07 |

| Amezcua-Prieto et al., 2019 Spain [21] | Case-control | NR | NR | 518 | Industrial sweets | SGA | Intake of industrial sweets associated with odds of having an SGA newborn (OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.42, 5.13). |

| Ancira-Moreno et al., 2020 Mexico [53] | Prospective Cohort | 25.08 ± 5.8 | 2nd and 3rd trimester | 660 | Mixed dietary patterns (sugary drinks, juices and sodas, red and processed meat, cereals) | LBW | The mixed dietary pattern associated risk LBW infant: (OR: 1.58; 95% CI: 0.63, 3.44) |

| Angali, Shahri, Borazjani, 2020, Iran [42] | Prospective Cohort | ≥18 years | <13 weeks | 488 | “High fat - fast food” pattern (refined cereal, processed meat and high-fat dairy and juices) | GWG and hyperglycemia | High fat-fast food patterns associated with higher GWG (β: 0.029; 95% CI: 0.012, 0.049). |

| Asadi et al., 2019 Iran [38] | Case-control | case: 29 ± 5.17 control: 27.5 ± 4.92 | 24–28 weeks | case: 130 control: 148 | WDP (SSB, refined grain products, fast foods, salty snacks, sweets and biscuit, mayonnaise) | GDM | The prudent dietary pattern associated with GDM risk: (OR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.44, 0.99) |

| Barbosa et al., 2021 Brazil [52] | Prospective Cohort | >14 | 22–25 weeks | 2750 | Soft drinks | Gestational Hypertension (GH) | Soft drink consumption > 7 times per week associated with GH: (RR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.82; p = 0.001) |

| Bärebring et al., 2016 Sweden [84] | Prospective Cohort | 32.1 (IQR: 30.8–35.3) | 35.9 weeks (IQR: 35.1–36.4) | 95 | Snacks pattern (sweets, cakes, biscuits, potato chips, popcorn) | GWG | Snacks pattern associated with excessive GWG (OR: 1.018; 95% CI: 1.004, 1.032). |

| Baskin et al., 2015 Australia [88] | Prospective Cohort | 30.55 ± 4.24 | 16 weeks | 167 | Unhealthy dietary patterns (sweets and desserts, refined grains, high- energy drinks, fast foods, hot chips, high-fat dairy, fruit juice and red meats) | Depressive symptoms | An unhealthy diet at T2 is associated with depressive symptoms: β: 0.19; 95% CI=0.04, 0.34; p < 0.05 |

| Borgen et al., 2012 Norway [75] | Prospective Cohort | >18 years | 15 weeks | 32,933 | SSB | Preeclampsia | Sugar-sweetened beverages associated with increased risk of preeclampsia: OR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.54 |

| Brantsæter et al., 2009 Norway [76] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | 20.7 weeks (SD ± 3.7) | 23,423 | Dietary patterns (Processed meat products, white bread, French fries, salty snacks, and sugar-sweetened drinks) | Risk of preeclampsia | Processed food patterns are associated with increased risk of developing preeclampsia (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.42). |

| Chen et al., 2009 USA [56] | Prospective Cohort | 24–44 | NR | 13,475 | SSB | Risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) | Intake of sugar-sweetened cola associated with risk of GDM (RR: 1.22; 95% Cl: 1.01, 1.47). |

| Chen et al., 2020 China [35] | Case-control | case: 28 ± 1.3 control: 28 ± 1.5 | >22 weeks | case: 1290 control: 1290 | High-salt pattern (pickled vegetables, processed and cooked meat, fish and shrimp, bacon and salted fish, bean sauce) | Hypertensive disorder during pregnancy | High-salt pattern diets associated with higher systolic blood pressure: (r: 0.110; p < 0.05) |

| Coelho et al., 2015 Brazil [63] | Prospective Cohort | 24.7 ± 6.1 | ≥22 weeks | 1298 | Snack dietary patterns (sandwich cookies, salty snacks, chocolate, and chocolate drink) | Birth weight | Snack dietary patterns positively associated with birth weight: (β: 56.64; p = 0.04) in pregnant adolescents. |

| Dale et al., 2019 Norway [79] | Prospective Cohort | ≥18 | 16-18 weeks | 88,514 | SSB | CHD | 25–70 mL/day sucrose-sweetened soft beverages associated with non-severe CHD (RR:1.30; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.58) and (RR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.52) for ≥70 mL/day. |

| Dominguez et al., 2014 Spain [74] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | NR | 3048 | Fast food | GDM | Fast food consumption associated with GDM risk: (OR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.13, 3.06) |

| Donazar-Ezcurra et al., 2017 Spain [71] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | NR | 3455 | WDP (red meat, high-fat processed meats, potatoes, commercial bakery products, whole dairy products, fast foods, sauces, pre-cooked foods, eggs, soft drinks and sweets, chocolates) | GDM | The Western dietary pattern associated with GDM incidence: (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.00, 2.43; p = 0.05) |

| Donazar-Ezcurra et al., 2017 Spain [72] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | NR | 3396 | Soft drinks | GDM | Sugar-sweetened soft drinks (SSSD) associated with GDM: (OR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.28, 3.34; p: 0.004) |

| Englund-Ögge et al., 2014 Norway [85] | Prospective Cohort | <20 to ≥40 | 15 weeks | 66,000 | WDP (salty snacks, chocolates and sweets, French fries, cakes, white bread, ketchup, dairy desserts, SSB, mayonnaise, processed meat, waffles, pancakes, cookies) | Preterm delivery | Western diet pattern associated with risk of preterm delivery (Hazard Ratio: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.92, 1.13). |

| Englund-Ögge et al., 2019 Norway [68] | Prospective Cohort | >18 years | 15 weeks | 65,904 | WDP (salty snacks, chocolate and sweets, cakes, French fries, white bread, ketchup, SSB, processed meat products, and pasta) | LGA | The prudent pattern associated with decreased LGA risk: (OR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.75, 0.94) The traditional group associated with increased LGA risk: (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.24) |

| Ferreira et al., 2022 Brazil [89] | Cross-sectional | 28 (IQR 19–45) | NR | 260 | Dietary patterns (sweets, snacks and cookies) | GWG | Women with greater adherence to “Pattern 2” (sweets, snacks, and cookies) during pregnancy were less likely to have inadequate GWG (OR: 0.14; 95% CI = 0.03, 0.60) |

| Garay et al., 2019 United Kingdom [80] | Cross-sectional | 18–45 years | NR | 303 | WDP (cakes/biscuits/ice cream, chips/crisps, processed meat, takeout, chocolate, soft drinks) | CBWC | Health-conscious dietary pattern associated with increased CBWC (OR: 4.75; 95% CI: 1.17, 8.33; p = 0.010) “Western Diet” associated with increased CBWC (β: −2.64; 95% CI: −5.87, 0.59; p = 0.109) |

| Gomes et al., 2020 Brazil [18] | Prospective Cohort | ≥18 years | All trimesters | 259 | UPF energy (cookies, sweets, SSB, reconstituted meats, crackers, packaged chips, frozen dinners, ultra-processed breads) | GWG | Energy percentage derived from UPF associated with average weekly GWG (β: 4.17; 95% CI 0.55, 7.79). |

| Grieger, et al., 2014 Australia [22] | Cross-sectional | >18 | 13 weeks | 309 | Dietary patterns (high-fat/sugar/takeaway: takeaway foods, potato chips, refined grains, and added sugar) | Preterm delivery | High-fat/sugar/takeaway pattern associated with preterm birth: (OR: 1.54; 95% CI: 1.10, 2.15; p = 0.011) |

| Grundt et al., 2016 Norway [73] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | 15 weeks | 50,280 | SSC | BW | Each 100 mL intake of SSC associated with: 7.8 g decrease in BW (95% CI: −10.3, 5.3); decreased risk of BW > 4.5 kg (OR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.90, 0.97) and increased risk of BW < 2.5 kg (OR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.10). |

| Günther et al., 2019 Germany [66] | Prospective Cohort | 30.3 ± 4.4 | <12 weeks | 1995 | Fast foods | LGA | Fast food consumption associated with LGA: (OR 3.14; 95% CI: 1.26,7.84; p = 0.014) |

| Hajianfar et al., 2018 Iran [39] | Prospective Cohort | 20–40 | 8–16 weeks | 812 | WDP (processed meats, fruits juice, citrus, nuts, desserts and sweets, potato, legumes, coffee, egg, pizza, high fat dairy, and soft drinks) | Preeclampsia Hypertension | The Western dietary pattern is associated with: Preeclampsia: (OR: 2.08; 95% CI: 1,4.36, p = 0.02) High systolic blood pressure: (OR: 0.13; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.42; p = 0.002) |

| Hajianfar et al., 2018 Iran [40] | Prospective Cohort | 29.4 ± 4.85 | 8–16 weeks | 812 | WDP (processed meats, fruits juice, citrus, nuts, desserts and sweets, potato, legumes, coffee, egg, pizza, high fat dairy, and soft drinks) | LBW | Western dietary pattern (top quartile) associated with LBW infant: (OR: 5.51; 95% CI: 1.82, 16.66; p = 0.001) |

| Hirko et al., 2020 USA [58] | Prospective Cohort | mean: 27 | mean: 13.4 weeks | 327 | Dietary patterns (added sugar: soda, fruit-flavored drinks with sugar, pastries—donuts, sweet rolls, Danish, and cookies, cake, pie, or brownies) | GWG | Higher added sugar intake associated with excessive GWG (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.84, 0.99) |

| Ikem et al., 2019 Denmark [20] | Prospective Cohort | 25–30 | 12 weeks | 55,139 | WDP (potatoes, French fries, bread white, pork, beef veal, meat mixed, meat cold and dressing sauce) | Gestational hypertension Preeclampsia | Western diet associated with GH: (OR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.33) Preeclampsia: (OR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.76): |

| Itani et al., 2020 United Arab Emirates [36] | Prospective Cohort | 19–40 | 27–42 weeks | 242 | WDP (sweets, sweetened beverages, added sugars, fast food, eggs, and offal) | GWG | The Western pattern is associated with excessive gestational weight gain (OR: 4.04; 95% CI: 1.07, 15.24)The western pattern is associated with gestational weight gain rate (OR: 4.38; 95% CI: 1.28, 15.03) |

| Ker et al., 2021 Taiwan [46] | Prospective Cohort | 33.9 ± 4.6 | All trimesters | 196 | SSB | Postpartum depression | SSB intake associated with increased EPDS scores: (β: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.45) during the first and second trimesters |

| Lamyian et al., 2017 Iran [19] | Prospective Cohort | 18–45 years | ≤6 weeks | 1026 | Fast food | GDM | Fast food consumption (≥175 g/week) associated with GDM risk: (OR: 2.12; 95% CI: 1.12, 5.43; p-trend: 0.03 |

| Liu et al., 2021 China [47] | Cross-sectional | 26.88 ± 4.62 | All trimesters | 7934 | Dietary patterns (snacks pattern: beverages, sweetmeat, fast-food, dairy and eggs) | Macrossomia SGA | Snacks pattern associated with: risk of macrosomia: (OR: 1.265; 95% CI: 1.000, 1.602) SGA: (OR: 1.260; 95% CI: 1.056, 1.505). |

| Loy, Marhazlina; Jan 2013 Malaysia [43] | Cross-sectional | 29.7 ± 4.8 | 33.66 ± 3.95 weeks | 108 | Dietary patterns (confectioneries: cake, cookies, chocolate, candy, sweetened condensed milk) | LBW | Confectioneries food intake associated with lower birth weight: (β: −1.999; p = 0.013) |

| Marí-Sanchiz et al., 2017 Spain [69] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | NR | 3298 | UPF (Processed meat) | GDM | Processed meat consumption associated with GDM: (OR: 2.01; 95% CI: 1.26, 3.21; p-trend 0.003) |

| Marquez, 2012 USA [64] | Cross-sectional | 18–49 | ≥37 weeks | 290 | SSB | GWG | A high intake of regular soda is associated with an increased risk of Excessive GWG (OR: 1.41; 95% CI: 0.60, 3.31). |

| Martin et al., 2016 Sweden [59] | Prospective Cohort | 16–47 | 39 ± 2 weeks | 389 | Dietary patterns (latent class 3: white bread, red and processed meats, fried chicken, French fries, and vitamin C–rich drinks) | BMI-for-age at birth | Association between the latent class 3 diet (processed food) and BMI-for-age z-score at birth:(β: −0.41; 95% CI: −0.79, −0.03). |

| Martin et al., 2015 USA [55] | Prospective Cohort | NR | 24–29 weeks | 3941 | Dietary patterns (hamburgers or cheeseburgers, white potatoes, fried chicken, beans, corn, spaghetti dishes, cheese dishes, processed meats, biscuits, and ice cream) | Preterm birth | Diet characterized by ultra-processed food associated with preterm birth: (OR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.30) |

| Maugeri et al., 2019 Italy [67] | Prospective Cohort | 15–50 (Mean: 37) | 4–20 weeks (Mean: 16) | 232 | WDP (high intake of red meat, fries, dipping sauces, salty snacks and alcoholic drinks) | GWG | Western dietary patterns associated with GWG: (β: 1.217; Standard Error: 0.487; p = 0.013) |

| Mikeš et al., 2021 Czech Republic [86] | Prospective Cohort | 25 ± 5 | 32 weeks | 4320 | Unhealthy Dietary pattern: (pizza, fish products, processed meat, sausages, smoked meat, hamburgers, and confectionary foods, sugary drinks, cakes, chocolate and sweets). | Birth Weight Birth Length | A 1-unit increase in the unhealthy pattern score was associated with a mean birth weight reduction of −23.8 g (95% CI: −44.4, −3.3; p = 0.023); a mean birth length reduction of −0.10 cm (95% CI: −0.19, −0.01; p = 0.040). |

| Mitku et al., 2020 South Africa [50] | Prospective Cohort | <25 to >30 | 1st and 2nd trimesters | 687 | Junk food (sweets, muffins, chips, mixed salad, fruit juice, fizzy soft drinks, vetkoek, coffee creamer, cooking oil, hamburgers, cooked vegetables, cereals rice, margarine) | Birth Weight | Junk food intake is associated with an increase in birth weight (p < 0.001). |

| Nascimento et al., 2016 Brazil [62] | Prospective Cohort | 26.2 ± 5.8 | 26.4 weeks (SD ± 0.8) | 841 | WDP (white bread, savory, sweet, chocolate, cookies, soft drinks, pasta, fried food, pizza, chicken, canned food) | GDM | Association between GDM incidence and dietary patterns (RR: 0.78; 95%CI: 0.43, 1.43) |

| Nicolì et al., 2021 Italy [78] | Prospective Cohort | 35.75 ± 5.53 | NR | 376 | Soft drink | GDM | Non-nutritive-sweetened soft drink consumption associated with GDM (OR: 1.766; 95% CI: 1.089, 2.863; p = 0.021) |

| Okubo et al., 2012 Japan [44] | Prospective Cohort | ≥18 | All trimesters | 803 | Dietary patterns (wheat products pattern: bread, confectioneries, fruit and vegetable juice, and soft drinks) | SGA birth | Wheat products pattern associated with SGA infant: (OR: 5.2; 95% CI: 1.1, 24.4) |

| Rasmussen et al., 2014 Denmark [83] | Prospective Cohort | 21–39 | 2nd trimester | 69,305 | WDP (French fries, white bread, meat mixed, margarine, dressing sauce, chocolate milk, soft drink, cakes, chocolate, candy, sweet spread, dessert dairy) | Preterm Birth | Western diet associated with preterm delivery (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.49) |

| Rodrigues, Azeredo, Silva, 2020, Brazil [65] | Cross-sectional | 24.9 ± 6.5 | 39.4 weeks (SD ± 1.2) | 99 | Processed meat | LBW | Maternal consumption of sausages associated with LBW: (OR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.10) |

| Rohatgi et al., 2017 USA [4] | Prospective Cohort | 27.2 ± 5.1 | 32–37 weeks | 45 | UPF energy intake | GWG | Each 1% increase in UPF energy intake associated with increase in GWG: (β: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.3, 2.4; p = 0.016) |

| Schmidt et al., 2020 Denmark [70] | Prospective Cohort | NR | 12 weeks | 66,387 | Soft drinks | CHD | High intake of sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages (≥4 servings) associated with CHD: (OR: 2.41; 95% CI: 1.26, 4.64; p-trend = 0.03.) |

| Sedaghat et al., 2017 Iran [41] | Case-control | case: 29.64 ± 4.52 control: 29.76 ± 4.26 | case: 29.39 ± 4.74 weeks control: 31.19 ± 3.53 weeks | case: 122 control: 266 | WDP (sweet snacks, mayonnaise, SSB, salty snacks, solid fats, high-fat dairy, red and processed meat, and tea and coffee) | GDM | Western dietary patterns associated with GDM risk: (OR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.04, 2.27) |

| Tamada et al., 2021 Japan [48] | Prospective Cohort | 30.7 years (SD ± 5.1) | 14.4 weeks (SD ± 5.6) | 94,062 | Ready-made meals (pre-packed foods, instant noodles, soup) | Stillbirth Preterm Birth LBW | Ready-made meals associated with stillbirth: (OR: 2.632; 95% CI: 1.507, 4.597; q = 0.007); Preterm birth: (OR: 0.993; 95% CI: 0.887, 1.125) LBW: (OR: 0.961; 95% CI: 0.875, 10.56) |

| Teixeira et al., 2020 Brazil [60] | Prospective Cohort | mean: 25.9 | 10–11 weeks | 299 | Dietary patterns (processed meats, sandwiches and snacks, sandwich sauces, desserts and sweets, soft drinks) | SGA | Dietary pattern with snacks, sandwiches, sweets, and soft drinks associated with the risk to deliver SGA babies: (RR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.08, 3.39) |

| Tielemans et al., 2015 Netherlands [81] | Prospective Cohort | 31.6 (IQR ± 4.3) | 13.4 weeks (IQR: 12.2–15.5) | 3374 | Dietary patterns (margarine—solid and liquid, sugar and confectionary, cakes, chocolate, candy, snacks) | GWG | Margarine, sugar, and snacks pattern are associated with a higher prevalence of excessive GWG: (OR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.99) |

| Uusitalo et al., 2009 Finland [77] | Prospective Cohort | 29.2 ± 5.2 | 10 weeks | 3360 | Dietary patterns (fast food: sweets, fast food, snacks, chocolate, fried potatoes, soft drinks, high-fat pastry, cream, fruit juices, white bread, processed meat, sausage) | GWG | Fast food patterns associated with weight gain rate: (β: 0.010; SE: 0.003; p = 0.004) |

| Wen et al., 2013 Australia [87] | Prospective Cohort | >16 | 24–34 weeks | 368 | Junk food diet (soft drinks, processed meat, meals, chips or French fries) | LGA | Junk food diet versus without a junk food diet associated with a newborn LGA: (OR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.91; p = 0.03) |

| Wrottesley, Pisa & Norris, 2017; South Africa [51] | Prospective Cohort | ≥18 | All trimesters | 538 | WDP (white bread, cheese and cottage cheese, red meat, processed meat, roast potatoes and chips, sweets, chocolate, soft drinks, miscellaneous) | GWG | Western dietary pattern associated with excessive GWG (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.78, 1.45; p = 0.682) |

| Yong et al., 2021 Malaysia [49] | Prospective Cohort | 30.01 ±4.48 | 1st trimester | 452 | Beverages (carbonated and juices) | GDM | Higher fruit juice intake associated with GDM (OR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.89, 0.98). |

| Zareei et al., 2019 Iran [45] | Cross-sectional | 28.96 ± 5.85 | NR | 82 | Dietary patterns (unhealthy dietary patterns: mayonnaise, fries, red meat, soft drinks, pizza, snacks, sweets and dessert, refined cereal, hydrogenated oils, high-fat dairy products, sugar, processed meat, broth.) | Preeclampsia | The unhealthy dietary pattern associated with preeclampsia (OR: 1.381; 95% CI: 0.462, 4.126, p = 0.564) |

| Zhang et al., 2006 USA [57] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | NR | 13,110 | WDP (red and processed meat, refined grain products, sweets, French fries and pizza) | GDM | Western pattern score associated with GDM risk (RR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.20, 2.21; p = 0.001); Red meat associated with GDM risk: (RR: 1.61; 95% CI: 1.25, 2.07) Processed meat associated with GDM risk: (RR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.13, 2.38) |

| Zhu et al., 2017 Denmark [82] | Prospective Cohort | >18 | 25 weeks | 918 | Soft drinks | Birth weight | Daily soft drinks consumption associated with offspring risk of LGA: (RR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.05, 2.35) |

| Zuccolotto et al., 2019 Brazil [61] | Cross-sectional | 27.6 ± 5.4 | 24–39 weeks | 785 | Snack dietary patterns (breads; butter and margarine; Processed meat, sweets, chocolate milk and cappuccino) | GDM | Dietary patterns associated with GDM risk: (OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.63, 1.63) |

| Outcomes | Studies (n, References) | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency a | Indirectness b | Imprecision c | Publication Bias | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Outcomes | |||||||

| Excessive Gestational Weight Gain | 5 [36,51,58,81,84] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Gestational Weight Gain | 5 [4,18,42,67,77] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Gestational Diabetes Mellitus | 10 [19,49,56,57,62,69,71,72,74,78] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | strongly suspected e | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Gestational Hypertension | 3 [20,39,52] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Preeclampsia | 4 [20,39,75,76] | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

| Neonatal Outcomes | |||||||

| Low Birth Weight | 5 [40,44,48,53,73] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Large for Gestational Age | 3 [54,66,73] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Preterm Birth | 4 [48,55,83,85] | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not assessed d | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paula, W.O.; Patriota, E.S.O.; Gonçalves, V.S.S.; Pizato, N. Maternal Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods-Rich Diet and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153242

Paula WO, Patriota ESO, Gonçalves VSS, Pizato N. Maternal Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods-Rich Diet and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(15):3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153242

Chicago/Turabian StylePaula, Walkyria O., Erika S. O. Patriota, Vivian S. S. Gonçalves, and Nathalia Pizato. 2022. "Maternal Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods-Rich Diet and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 14, no. 15: 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153242

APA StylePaula, W. O., Patriota, E. S. O., Gonçalves, V. S. S., & Pizato, N. (2022). Maternal Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods-Rich Diet and Perinatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(15), 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153242