Role of Phytoestrogen-Rich Bioactive Substances (Linum usitatissimum L., Glycine max L., Trifolium pratense L.) in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

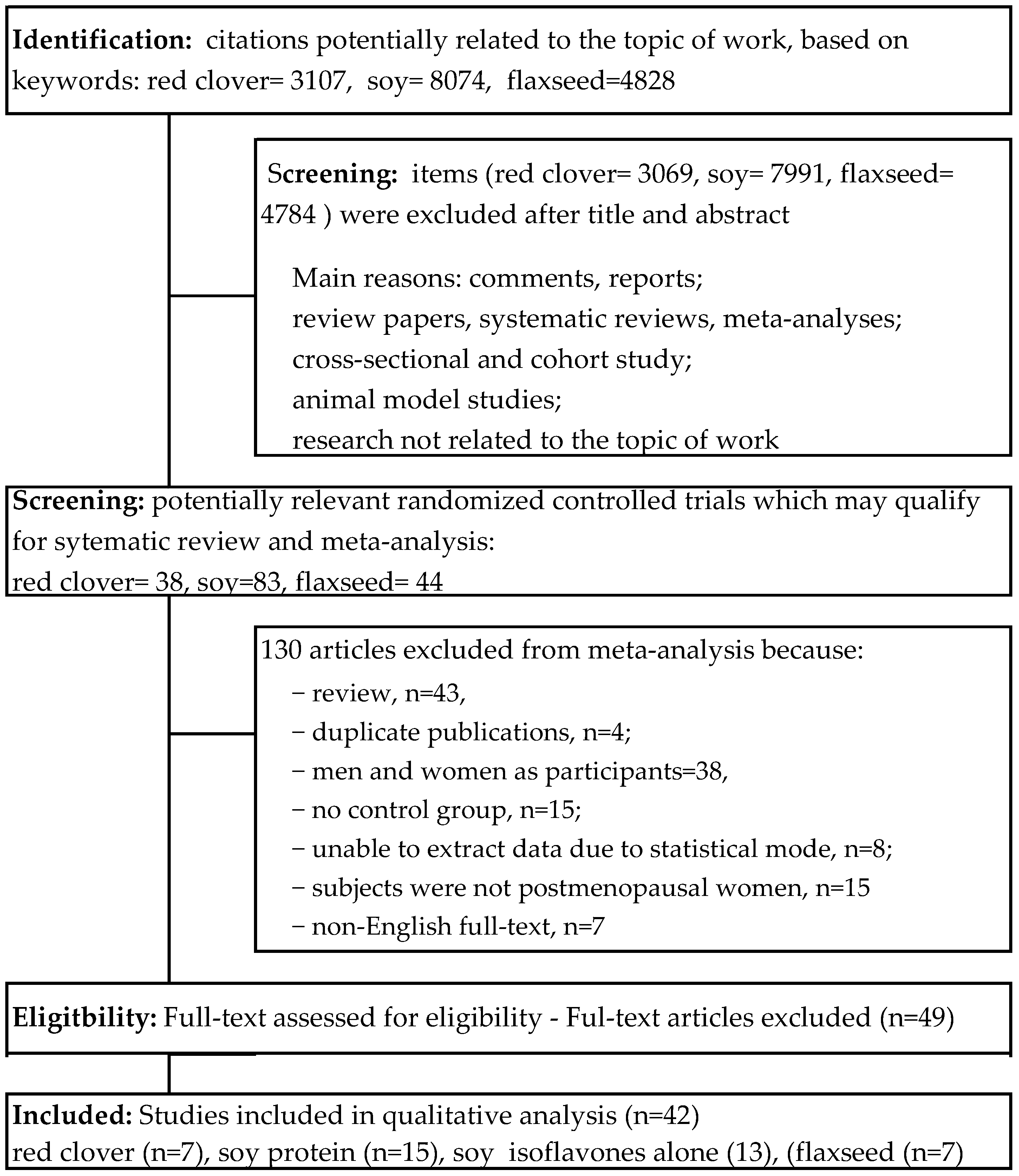

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Quality Assessment and Bias Risk of the Trials

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Meta-Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Trials

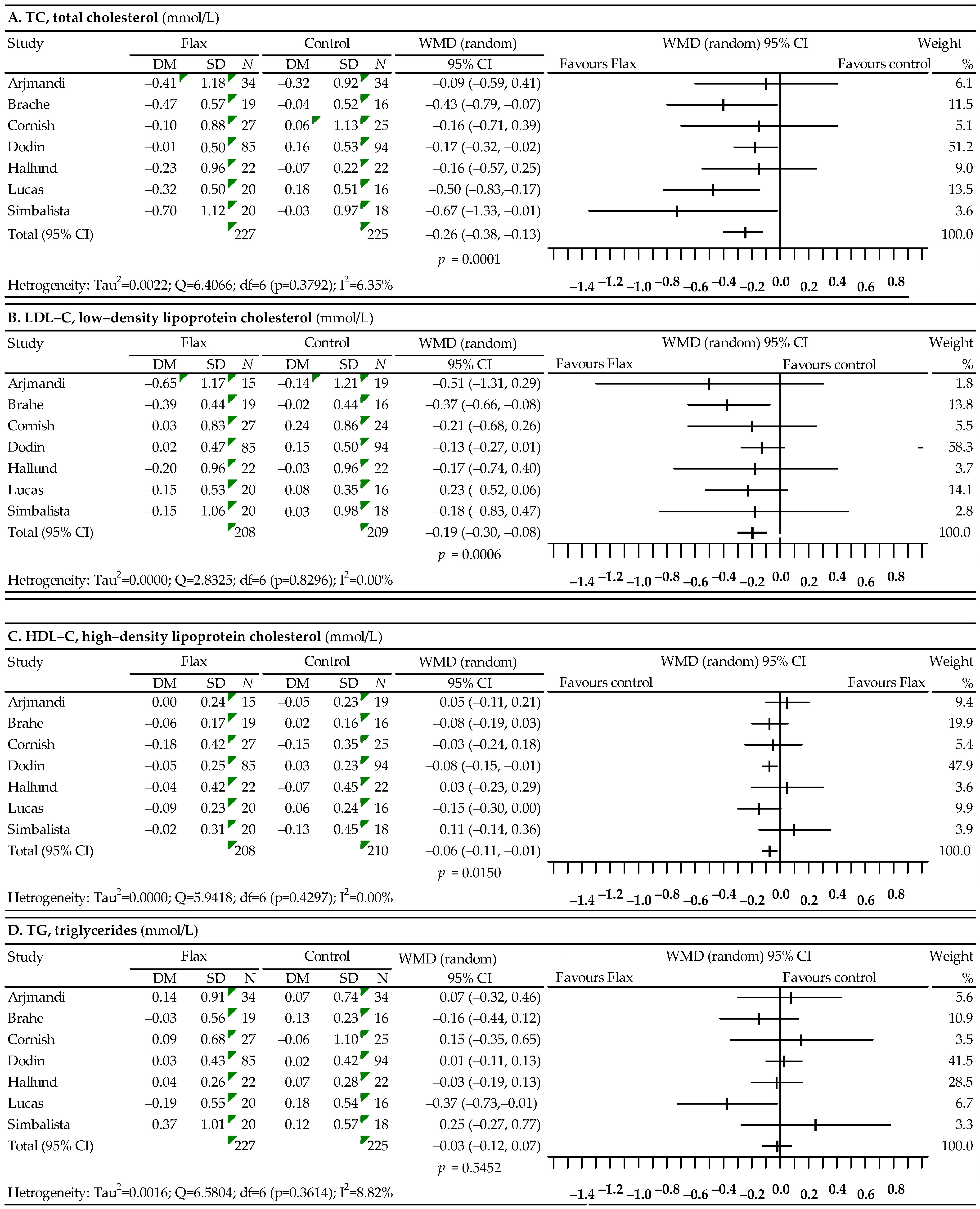

3.2. Associations between Flaxseed and Plasma Lipid Profiles

3.3. Associations between Soy Protein without and with Isoflavones and Lipid Profiles

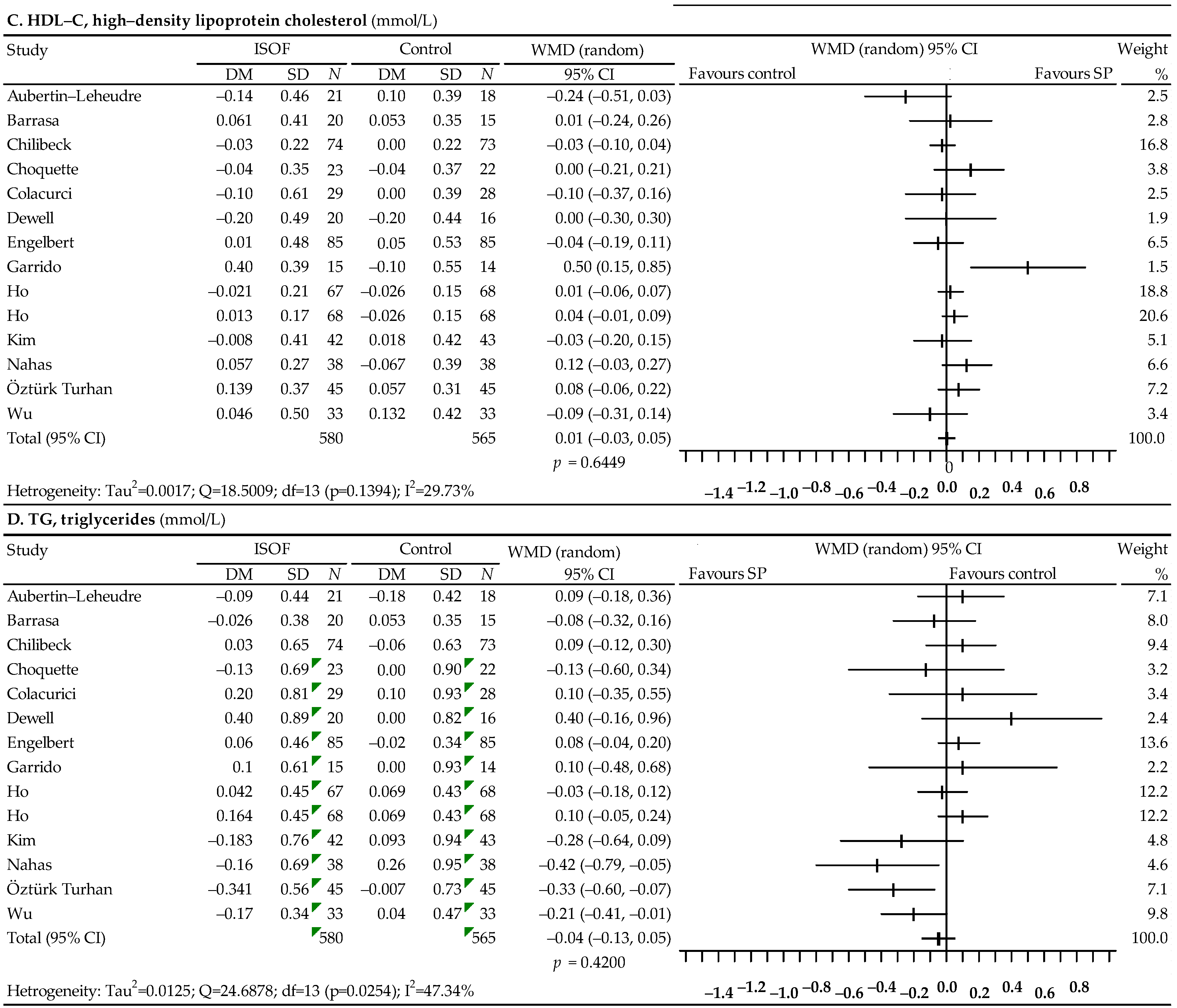

3.4. Associations between Soy Isoflavones Alone (Preparation) and Lipid Profiles

3.5. Associations between Red Clover and Lipid Profiles

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Lin, L.; Wu, H.; Yan, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Li, H. Global, Regional, and National Death, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) for Cardiovascular Disease in 2017 and Trends and Risk Analysis From 1990 to 2017 Using the Global Burden of Disease Study and Implications for Prevention. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 559751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAloon, C.J.; Boylan, L.M.; Hamborg, T.; Stallard, N.; Osman, F.; Lim, P.B.; Hayat, S.A. The changing face of cardiovascular disease 2000−2012: An analysis of the world health organization global health estimates data. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 224, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wautier, J.L.; Wautier, M.P. Endothelial cell participation in inflammatory reaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munakata, M. Clinical significance of stress-related increase in blood pressure: Current evidence in office and out-of-office settings. Hypertens. Res. 2018, 41, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiraiah, A. Hyperglycemia, lipoprotein glycation, and vascular disease. Angiology 2005, 56, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirro, M.; Bianconi, V.; Paciullo, F.; Mannarino, M.R.; Bagaglia, F.; Sahebkar, A. Lipoprotein(a) and inflammation: A dangerous duet leading to endothelial loss of integrity. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 119, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstädter, J.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Vascular inflammation and oxidative stress: Major triggers for cardiovascular disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 7092151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Dimitriadis, G.; Zampelas, A. Metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk factors. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2013, 11, 858–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, T.M.; Pedley, A.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Fox, C.S. Association between visceral and subcutaneous adipose depots and incident cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circulation 2015, 132, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Cai, X.; Mai, W.; Li, M.; Hu, Y. Association between prediabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016, 355, i5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G.J.; Thanassoulis, G.; Anderson, T.J.; Barry, A.R.; Couture, P.; Dayan, N.; Francis, G.A.; Genest, J.; Grégoire, J.; Grover, S.A.; et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 1129–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phung, O.J.; Makanji, S.S.; White, C.M.; Coleman, C.I. Almonds have a neutral effect on serum lipid profiles: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2009, 109, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahinfar, H.; Bazshahi, E.; Amini, M.R.; Payandeh, N.; Pourreza, S.; Noruzi, Z.; Shab-Bidar, S. Effects of artichoke leaf extract supplementation or artichoke juice consumption on lipid profile: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6607–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, A.; Arab, A.; Ghaedi, E.; Rafie, N.A.; Miraghajani, M.; Kafeshani, M. Barberry (Berberis vulgaris L.) is a safe approach for management of lipid parameters: A systematic review and meta—Analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 43, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebkar, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of curcumin on blood lipid levels. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmasoumi, M.; Hadi, A.; Rafie, N.; Najafgholizadeh, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Rouhani, M.H. The effect of ginger supplementation on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Phytomedicine 2018, 43, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.H.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, B.S.; Rong, Z.X.; Wang, B.S.; Su, B.H.; Chen, H.Z. Time- and dose-dependent effect of psyllium on serum lipids in mild-to-moderate hypercholesterolemia: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalesi, S.; Paukste, E.; Nikbakht, E.; Khosravi-Boroujeni, H. Sesame fractions and lipid profiles: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Liu, X.; Bai, Y.Y.; Li, S.H.; Sun, K.; He, C.; Hui, R. Short-term effect of cocoa product consumption on lipid profile: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuccinardi, D.; Farr, O.M.; Upadhyay, J.; Oussaada, S.M.; Klapa, M.I.; Candela, M.; Rampelli, S.; Lehoux, S.; Lázaro, I.; Sala-Vila, A.; et al. Mechanisms underlying the cardiometabolic protective effect of walnut consumption in obese people: A cross-over, randomized, double-blind, controlled inpatient physiology study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2019, 21, 2086–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, I.T.; de Almeida-Pititto, B.; Ferreira, S.R.G. Reassessing lipid metabolism and its potentialities in the prediction of cardiovascular risk. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 59, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meldrum, D.R.; Davidson, B.J.; Tataryn, I.V.; Judd, J.L. Changes in circulating steroids with aging in postmenopausal women. Obs. Gynecol. 1981, 57, 624–628. [Google Scholar]

- Derby, C.A.; Crawford, S.L.; Pasternak, R.C.; Sowers, M.; Sternfeld, B.; Matthews, K.A. Lipid changes during the menopause transition in relation to age and weight: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 119, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.J.; Min, Y.J.; Oh, M.S.; Kwon, J.E.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, W.S.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, M.A.; et al. Effects of the transition from premenopause to postmenopause on lipids and lipoproteins: Quantification and related parameters. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambikairajah, A.; Walsh, E.; Cherbuin, N. Lipid profile differences during menopause: A review with meta-analysis. Menopause 2019, 26, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostis, P.; Stevenson, J.C.; Crook, D.; Johnston, D.G.; Godsland, I.F. Effects of menopause, gender and age on lipids and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol subfractions. Maturitas 2015, 81, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.H.; Kim, H.S. Menopause-associated lipid metabolic disorders and foods beneficial for postmenopausal women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y.Y.; Gui, B.; Arnison, P.G.; Wang, Y. Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) bioactive compounds and peptide nomenclature: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 38, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.R.; Severino, P.; Ferreira, C.S.; Zielinska, A.; Santini, A.; Souto, S.B.; Souto, E.B. Linseed essential oil—Source of lipids as active ingredients for pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 4537–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitts, D.D.; Yuan, Y.; Wijewickreme, A.N.; Thompson, L.U. Antioxidant activity of the flaxseed lignan secoisolariciresinol diglycoside and its mammalian lignan metabolites enterodiol and enterolactone. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1999, 202, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghvi, A.; Divven, W.; Seltman, H. Inhibition of rat liver cholesterol 7-alpha hydroxylase and Acylotransferaza acylo-CoA: Cholesterol activities by entrodiol and enterolactone. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Drugs Affecting Lipid Metabolism; Kritchevsky, D., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Burdge, G. a-Linolenic acid metabolism in men and women: Nutritional and biological implications. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2004, 7, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyei, A. Bioactive proteins and peptides from soybeans. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2015, 7, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Torre-Villalvazo, I.; Tovar, A.R. Regulation of lipid metabolism by soy protein and its implication in diseases mediated by lipid disorders. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.S. Current perspectives on the beneficial effects of soybean isoflavones and their metabolites for humans. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, D.C.; Piazza, C.; Melilli, B.; Drago, F.; Salomone, S. Isoflavones: Estrogenic activity, biological effect and bioavailability. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 38, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Daneshzad, E.; Azadbakht, L. The effects of isolated soy protein, isolated soy isoflavones and soy protein containing isoflavones on serum lipids in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3414–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butteiger, D.N.; Hibberd, A.A.; McGraw, N.J.; Napawan, N.; Hall-Porter, J.M.; Krul, E.S. Soy protein compared with milk protein in a western diet increases gut microbial diversity and reduces serum lipids in Golden Syrian Hamsters. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Z.C.; Audinot, V.; Papapoulos, S.E.; Boutin, J.A.; Löwik, C.W.G.M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) as a molecular target for the soy phytoestrogen genistein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.P.M.; de Jesús, R.P.; Freire, T.O.; Oliveira, C.P.; Lyra, A.C.; Lyra, L.G.C. Possible molecular mechanisms soy-mediated in preventing and treating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Hosp. 2012, 27, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dentin, R.; Girard, J.; Postic, C. Carbohydrate responsive element binding protein (ChREBP) and sterol 42. regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c): Two key regulators of glucose metabolism and lipid synthesis in liver. Biochimie 2005, 87, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demonty, I.; Lamarche, B.; Deshaies, Y.; Jacques, H. Role of soy isoflavones in the hypotriglyceridemic effect of soy protein in the rat. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, W.; Wen, H.; Hou, X.; Li, D.; Kou, X. Potential lipid-lowering mechanisms of Biochanin A. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3842–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, S.; Hansen, U.; Niemann, B.; Palavinskas, R.; Lampen, A. Determination of the isoflavone composition and estrogenic activity of commercial dietary supplements based on soy or red clover. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemežiene, N.; Padarauskas, A.; Butkuté, B.; Ceseviĕciené, J.; Taujenis, L.; Norkeviĕciené, E. The concentration of isoflavones in red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) at flowering stage. Zemdirb. Agric. 2015, 102, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, N.L.; Overk, C.R.; Yao, P.; Burdette, J.E.; Nikolic, D.; Chen, S.N.; Bolton, J.L.; van Breemen, R.B.; Pauli, G.F.; Farnsworth, N.R. The chemical and biologic profile of a red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) phase II clinical extract. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2006, 12, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, N.L.; Overk, C.R.; Yao, P.; Totura, S.; Deng, Y.; Hedayat, A.S.; Bolton, J.L.; Pauli, G.F.; Farnsworth, N.R. Seasonal variation of red clover (Trifolium pratense L., Fabaceae) isoflavones and estrogenic activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaribazm, M.; Khazaei, F.; Naseri, L.; Pazhouhi, M.; Zamanian, M.; Khazaei, M. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of the Red Clover (Trifolium pratense L.): An overview of the new findings. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 41, 642–649. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T.; Ishida, J.; Nakagawa, S.; Ogawara, H.; Watanabe, S.; Itoh, N.; Shibuya, M.; Fukami, Y. Genistein, a specific inhibitor of tyrosine-specific protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 5592–5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobiger, S.; Jungbauer, A. Red clover extract: A source for substances that activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and ameliorate the cytokine secretion profile of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Menopause 2010, 17, 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Mark Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin. Trials. 1996, 17, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (Updated July 2020); John Wiley: Hooboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Follmann, D.; Elliott, P.; Suh, I.; Cutler, J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmandi, B.H.; AKhan, D.A.; Juma, S.; Drum, M.L.; Venkatesh, S.; Sohn, E.; Wei, L.; Derman, R. Whole flaxseed consumption lowers serum LDL-cholesterol and lipoprotein(a) concentrations in postmenopausal women. Nutr. Res. 1998, 18, 1203–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahe, L.K.; Le Chatelier, E.; Prifti, E.; Pons, N.; Kennedy, S.; Blaedel, T.; Hakansson, J.; Dalsgaard, T.K.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; et al. Dietary modulation of the gut microbiota—A randomized controlled trial in obese postmenopausal women. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornish, S.M.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Paus-Jennsen, L.; Biem, H.J.; Khozani, T.; Senanayake, V.; Vatanparast, H.; Little, J.P.; Whiting, S.J.; Pahwa, P. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of flaxseed lignan complex on metabolic syndrome composite score and bone mineral in older adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodin, S.; Lemay, A.; Jacques, H.; Legare, F.; Forest, J.C.; Masse, B. The effects of flaxseed dietary supplement on lipid profile, bone mineral density, and symptoms in menopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, wheat germ placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallund, J.; Ravn-Haren, G.; Bügel, S.; Tholstrup, T.; Tetens, I. A lignan complex isolated from flaxseed does not affect plasma lipid concentrations or antioxidant capacity in healthy postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, E.A.; Wild, R.D.; Hammond, L.J.; Khalil, D.A.; Juma, S.; Daggy, B.P.; Stoecker, B.J.; Arjmandi, B.H. Flaxseed improves lipid profile without altering biomarkers of bone metabolism in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 1527–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbalista, R.L.; Sauerbronn, A.V.; Aldrighi, J.M.; Arêas, J.A.G. Consumption of a flaxseed-rich food is not more effective than a placebo in alleviating the climacteric symptoms of postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.K.; Becker, D.M.; Kwiterovich, P.O.; Lindenstruth, K.A.; Curtis, C. Effect of soy protein-containing isoflavones on lipoproteins in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2007, 14, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaria, S.; Wisniewski, A.; Dupree, K.; Bruno, T.; Song, M.Y.; Yao, F.; Ojumu, A.; John, M.; Dobs, A.S. Effect of high-dose isoflavones on cognition, quality of life, androgens, and lipoprotein in post-menopausal women. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2009, 32, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.; Teng, H.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Weigel, R.M.; Klein, B.P.; Persky, V.W.; Freels, S.; Surya, P.; Bakhit, R.M.; Ramos, E.; et al. Long-term intake of soy protein improves blood lipid profiles and increases mononuclear cell low-density-lipoprotein receptor messenger RNA in hypercholesterolemic, postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.C.; Khalil, D.A.; Payton, M.E.; Arjmandi, B.H. One-year soy protein supplementation does not improve lipid profile in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2010, 17, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, A.M.; Irribarra, V.L.; Castillo, O.A.; Yañez, M.D.; Germain, A.M. Isolated soy protein improves endothelial function in postmenopausal hypercholesterolemic women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalais, F.S.; Ebeling, P.R.; Kotsopoulos, D.; McGrath, B.P.; Teede, H.J. The effects of soy protein containing isoflavones on lipids and indices of bone resorption in postmenopausal women. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003, 58, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.D.; Newell, K.A.; Cherin, R.; Haskell, W.L. The effect of soy protein with or without isoflavones relative to milk protein on plasma lipids in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.K.; Soares, J.M., Jr.; Haidar, M.A.; de Lima, G.R.; Baracat, E.C. Benefits of soy isoflavone therapeutic regimen on menopausal symptoms. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 99, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jassi, H.K.; Jain, A.; Arora, S.; Chitra, R. Effect of soy proteins vs. soy isoflavones on lipid profile in postmenopausal women. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 25, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kreijkamp-Kaspers, S.; Kok, L.; Grobbee, D.E.; de Haan, E.H.; Aleman, A.; Lampe, J.W.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Effect of soy protein containing isoflavones on cognitive function, bone mineral density, and plasma lipids in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 292, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.M.; Ho, S.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Ho, Y.P. The effects of isoflavones combined with soy protein on lipid profiles, C-reactive protein and cardiovascular risk among postmenopausal Chinese women. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 22, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maesta, N.; Nahas, E.A.P.; Nahas-Neto, J.; Orsatti, F.L.; Fernandes, C.E.; Traiman, P.; Burini, R.C. Effects of soy protein and resistance exercise on body composition and blood lipids in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 2007, 56, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, F.M.; Guthrie, N.L.; Villablanca, A.C.; Kumar, K.; Murray, M.J. Soy protein with isoflavones has favorable effects on endothelial function that are independent of lipid and antioxidant effects in healthy postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Dalais, F.S.; Kotsopoulos, D.; McGrath, B.P.; Malan, E.; Gan, T.E.; Peverill, R.E. Dietary soy containing phytoestrogens does not activate the hemostatic system in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1936–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vigna, G.B.; Pansini, F.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Albertazzi, P.; Donegà, P.; Zanotti, L.; De Aloysio, D.; Mollica, G.; Fellin, R. Plasma lipoproteins in soy-treated postmenopausal women: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2000, 10, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Lord, C.; Khalil, A.; Dionne, I.J. Effect of 6 months of physical activity and isoflavone supplementation on clinical cardiovascular risk factors in obese postmenopausal women: A randomized, double-blind study. Menopause 2007, 14, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrasa, G.R.R.; Canete, N.G.; Boasi, L.E.V. Age of postmenopause women: Effect of soy isoflavone in lipoprotein and inflammation markers. J. Menopausal. Med. 2018, 243, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilibeck, P.D.; Vatanparast, H.; Pierson, R.; Case, A.; Olatunbosun, O.; Whiting, S.J.; Beck, T.J.; Pahwa, P.; Biem, H.J. Effect of exercise training combined with isoflavone supplementation on bone and lipids in postmenopausal women: A randomized clinical trial. J. Bone Miner Res. 2013, 28, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choquette, S.; Riesco, É.; Cormier, É.; Dion, T.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Dionne, I.J. Effects of soya isoflavones and exercise on body composition and clinical risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in overweight postmenopausal women: A 6-month double-blind controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewell, A.; Hollenbeck, C.B.; Bruce, B. The effects of soy-derived phytoestrogens on serum lipids and lipoproteins in moderately hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbert, A.K.; Soukup, S.T.; Roth, A.; Hoffmann, N.; Graf, D.; Watzl, B.; Kulling, S.E.; Bub, A. Isoflavone supplementation in postmenopausal women does not affect leukocyte LDL receptor and scavenger receptor CD36 expression: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2008–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, A.; De la Maza, M.P.; Hirsch, S.; Valladares, L. Soy isoflavones affect platelet thromboxane A2 receptor density but not plasma lipids in menopausal women. Maturitas 2006, 54, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Ho, S.S.S.; Woo, J.L.F. Soy isoflavone supplementation and fasting serum glucose and lipid profile among postmenopausal Chinese women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause 2007, 14, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, O.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Young, K.D.; Jeong, Y.H.; Choue, R. Isoflavone supplementation influenced levels of triglyceride and luteunizing hormone in Korean postmenopausal women. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2013, 36, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, E.A.P.; Nahas-Neto, J.; Orsatti, F.L.; Carvalho, E.P.; Oliveira, M.L.C.S.; Dias, R. Efficacy and safety of a soy isoflavone extract in postmenopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Maturitas 2007, 58, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk Turhan, N.O.; Duvan, C.I.; Bolkan, F.; Onaran, Y. Effect of isoflavone on plasma nitrite/nitrate, homocysteine, and lipid levels in Turkish women in the early postmenopausal period: A randomized controlled trial. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 39, 367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Oka, J.; Tabata, I.; Higuchi, M.; Toda, T.; Fuku, N.; Ezaki, J.; Sugiyama, F.; Uchiyama, S.; Yamada, K.; et al. Effects of isoflavone and exercise on BMD and fat mass in postmenopausal Japanese women: A 1-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Bone Miner Res. 2006, 21, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colacurci, N.; Chiàntera, A.; Fornaro, F.; de Novellis, V.; Manzella, D.; Arciello, A.; Chiàntera, V.; Improta, L.; Paolisso, G. Effects of soy isoflavones on endothelial function in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause 2005, 12, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.; Oosthuizen, W.; Scollen, S.; Loktionov, A.; Day, N.E.; Bingham, S.A. Modest protective effects of isoflavones from a red clover derived dietary supplement on cardiovascular disease risk factors in perimenopausal women, and evidence of an interaction with ApoE genotype in 49–65 year old women. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1759–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton-Bligh, P.B.; Nery, M.L.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Visvalingam, S.; Fulcher, G.R.; Byth, K.; Baber, R. Red clover isoflavones enriched with formononetin lower serum LDL cholesterol—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, G.E.; Hughes, C.L.; Robboy, S.J.; Agarwal, S.K.; Bievre, M. A double-blind randomized study on the effects of red clover isoflavones on the endometrium. Menopause 2001, 8, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, L.A.; Chedraui, P.A.; Morocho, N.; Ross, S.; San Miguel, G. The effect of red clover isoflavones on menopausal symptoms, lipids and vaginal cytology in menopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2005, 21, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.N.T.; Thorup, A.C.; Hansen, E.S.S.; Jeppesen, P.B. Combined red clover isoflavones and probiotics potently reduce menopausal vasomotor symptoms. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, M.N.T.; Thybo, C.B.; Lykkeboe, S.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Frette, X.; Christensen, L.P.; Jeppesen, P.B. Combined bioavailable isoflavones and probiotics improve bone status and estrogen metabolism in postmenopausal osteopenic women: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schult, T.M.; Ensrud, K.E.; Blackwell, T.; Ettinger, B.; Wallace, R.; Tice, J.A. Effect of isoflavones on lipids and bone turnover markers in menopausal women. Maturitas 2004, 48, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, A.; Askarpour, M.; Shekoufeh, S.; Ghaedi, E.; Symonds, M.E.; Miraghajani, M. Effect of flaxseed supplementation on lipid profile: An updated systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of sixty-two randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Xia, H.; Wan, M.; Lu, Y.; Xu, D.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Sun, G. Comparisons of the effects of different flaxseed products consumption on lipid profiles, inflammatory cytokines and anthropometric indices in patients with dyslipidemia related diseases: Systematic review and a dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, S.; Ho, S.C. Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein containing isoflavones on the lipid profile. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luís, A.; Domingues, F.; Pereira, L. Effects of red clover on perimenopausal and postmenopausal women’s blood lipid profile: A meta-analysis. Climacteric 2018, 21, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanadys, W.; Baranska, A.; Jedrych, M.; Religioni, U.; Janiszewska, M. Effects of red clover (Trifolium pratense) isoflavones on the lipid profile of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2020, 132, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author [Ref.] Data Location | Study Design Trial Duration | Study Population Age (Mean ± SD) y, ysm, BMI, Health Condition | Intervention (Daily Dose) | GroUp Studied | Number Sample | Baseline Lipids Values | Jadad Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total-C mmol/L | LDL-C mmol/L | HDL-C mmol/L | TAG mmol/L | |||||||

| A. Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) | ||||||||||

| Arjmandi [59] 1998 United States | Cross-over 6-week active phase 2-week washout. | Age 56.3 ± 6.5, ysm N/A, BMI 29.2 ± 7.4, obesity, hypercholesterolemia | WFX 38 g, ALA 8.5 g vs. placebo: sunflower seed (slice of bread or muffin) | FG CG | 15 19 | 5.95 ± 1.44 5.92 ± 1.36 | 4.12 ± 1.39 4.06 ± 1.34 | 0.93 ± 0.23 1.08 ± 0.23 | 1.28 ± 0.92 1.27 ± 0.70 | 4 |

| Lucas [64] 2002 United States | Parallel group 3-month follow-up | Age 54 ± 8, ysm N/A, BMI 29.1 ± 7.1 obesity | WFX 40 g vs. placebo, wheat-based 40 g | FG CG | 20 16 | 5.76 ± 1.12 5.95 ± 1.12 | 3.21 ± 1.12 3.52 ± 1.12 | 1.89 ± 0.42 1.61 ± 0.40 | 1.48 ± 0.71 1.56 ± 0.76 | 4 |

| Dodin [62] 2005 Canada | Parallel group 1-year follow-up | Age 54.0 ± 4.0, ysm 4.7 ± 5.2, BMI 25.5 ± 4.5 healthy | WFX 40 g, ALA 9.1 g vs. control, wheat germ (slice of bread or drinks) | FG CG | 85 94 | 5.67 ± 0.75 5.78 ± 0.71 | 3.43 ± 0.69 3.50 ± 0.64 | 1.72 ± 0.33 1.74 ± 0.39 | 1.12 ± 0.45 1.16 ± 0.57 | 5 |

| Hallund [63] 2006 Denmark | Cross-over 6-week active phase 6-week washout | Age 61 ± 7, ysm >24 mo, BMI 25.5 ± 4.5 healthy | Lignan complex, SDG 500 mg vs. control (in form muffins, 50 g) | FG CG | 22 22 | 6.05 ± 1.03 6.03 ± 0.98 | 3.80 ± 1.03 3.79 ± 0.98 | 1.81 ± 0.42 1.82 ± 0.52 | 0.96 ± 0.28 0.93 ± 0.33 | 4 |

| Cornish [61] 2009 Canada | Parallel group 6-month follow-up | Age 59.7 ± 5.3, ysm N/A, BMI 27.1 ± 5.3 healthy | Lignan complex, SGD 500 mg vs. placebo | FG CG | 27 25 | 5.87 ± 0.88 6.14 ± 1.05 | 3.60 ± 0.88 3.77 ± 0.80 | 1.74 ± 0.42 1.54 ± 0.40 | 1.19 ± 0.68 1.77 ± 1.10 | 4 |

| Simbalista [65] 2010 Brazil | Parallel group 3-month follow-up | Age 52.0 ± 2.9, ysm 3.8 ± 2.3, BMI 26 ± 3.6, healthy | GFX: WFX 25 g, SDG 46 mg, vs placebo: wheat bran (in form of slice bread) | FG CG | 20 18 | 6.03 ± 0.87 5.18 ± 0.93 | 3.83 ± 0.89 2.87 ± 0.93 | 1.61 ± 0.31 1.86 ± 0.42 | 1.49 ± 0.80 1.00 ± 0.54 | 5 |

| Brache [60] 2015 Denmark | Parallel group 6-week follow-up | Age 60.6 ± 6.4 y, ysm ≥1 y, BMI 35.2 ± 4.5, obesity | 10 g flaxseed mucilage vs. placebo: maltodextrin (in form buns) | FG CG | 19 16 | 6.39 ± 0.89 5.76 ± 0.69 | 4.11 ± 0.84 3.44 ± 0.74 | 1.40 ± 0.22 1.56 ± 0.42 | 1.51 ± 0.77 1.07 ± 0.32 | 3 |

| B. Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) | ||||||||||

| B. 1. Soy protein without and with isoflavones | ||||||||||

| Baum [68] 1998 United States | Parallel groups 2-week run-in/ 12-week follow-up | Age 60.8 ± 8.6 y, ysm N/A, BMI 27.8 ± 5.3, hypercholesterolemia | a. SP 40 g: a. IAE 90 mg; b. SP 40 g; IAE 56 mg vs. control, CP + MP 40 g | SG 90 SG 56 CG | 21 23 22 | 6.47 ± 0.88 6.57 ± 0.85 6.26 ± 0.67 | N/A N/A 4.9 ± 0.8 | 1.38 ± 0.32 1.34 ± 0.28 1.38 ± 0.31 | 1.74 ± 0.75 1.89 ± 1.02 1.75 ± 1.11 | 3 |

| Vigna [80] 2000 Italy | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 53.4 ± 3.3, ysm 2.4 y, BMI 25.9 ± 3.5, healthy | SP 40 g, IF 76 mg vs. control, CP 40 g | SG CG | 40 37 | 6.37 ± 1.01 6.55 ± 0.93 | 4.13 ± 0.87 4.33 ± 0.87 | 1.57 ± 0.36 1.61 ± 0.38 | 1.47 ± 0.90 1.32 ± 0.77 | 4 |

| Gardner [72] 2001 United States | Parallel groups 4-week run-in/ 12-week follow-up | Age 59.9 ± 6.6, ysm N/A, BMI 26.3 ± 4.6, hypercholesterolemia | a. SP 42 g b. SP 42 g (52 mg Gen, 25 mg Dai, 4 mg Gly) vs. control, MP 42 g. | SG SG CG | 33 31 30 | 5.9 ± 0.7 5.9 ± 0.6 6.1 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.6 3.9 ± 0.6 4.0 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.3 1.5 ± 0.3 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.5 1.3 ± 0.8 1.3 ± 0.7 | 4 |

| Han [73] 2002 Brazil | Parallel groups 4-month follow-up | Age 48.5 ± 7.6, ysm 1.9 ± 1.6 y, BMI 24.3 ± 3.2, healthy | SP 50.3 mg, IAE 23.3 mg Gen, 3.8 mg Gly, 6.2 mg Dai) vs. placebo | SG CG | 40 40 | 5.83 ± 0.88 5.86 ± 1.26 | 3.45 ± 0.87 3.45 ± 1.32 | 1.04 ± 0.23 1.03 ± 0.21 | 2.31 ± 1.66 1.99 ± 1.66 | 5 |

| Dalais [71] 2003 Australia | Parallel groups 3-month follow-up | Age 60 ± 6.2, ysm N/A, BMI 25.3 ± 4.6, healthy | SP 40 g, IC 118 mg (69 mg Agl) vs. control, CP 40 g | SG CG | 38 40 | 6.12 ± 0.92 5.92 ± 0.88 | 4.00 ± 0.86 3.69 ± 0.88 | 1.63 ± 0.49 1.72 ± 0.51 | 1.09 ± 0.68 1.01 ± 0.57 | 5 |

| Steinberg [78] 2003 United States | Cross-over 6-week active phase 4-week washout | Age 5.49 ± 5.29, ysm N/A, BMI 24.6 ± 3.2, healthy | a. SP 25 g b. SP 25 g, IAE 107 mg (55 mg Gen, 47 mg Dai, 5 mg Gly) vs. control, MP 25 g | SG a SG b CG | 24 24 24 | 4.91 ± 0.49 4.91 ± 0.49 4.91 ± 0.49 | 2.89 ± 0.49 2.89 ± 0.49 2.89 ± 0.49 | 1.55 ± 0.49 1.55 ± 0.49 1.55 ± 0.49 | 1.03 ± 0.49 1.03 ± 0.49 1.03 ± 0.49 | 4 |

| Cuevas [70] 2003 Chile | Cross-over 8-week active phase 4-week washout | Age 59 y, ysm 10 y, BMI 29.3 ± 3.43, obesity, hypercholesterolemia | SP 40 g, IAE 80 mg (60% Gen, 30% Dai, 10% Gly) vs. control, caseinate 40 g | SG CG | 18 18 | 7.90 ± 0.74 7.90 ± 0.74 | 5.04 ± 0.66 5.04 ± 0.66 | 1.39 ± 0.27 1.39 ± 0.27 | 2.18 ± 0.83 2.18 ± 0.83 | 4 |

| Kreijkamp- Kaspers [75] 2004 Netherlands | Parallel groups 12-month follow-up | Age 66.6 ± 4.7, ysm 17.9 ± 6.9 y, BMI 26.1 ± 3.8, healthy | SP 25.6 g, IAE 99 mg (52 mg Gen, 6 mg Gly, 41 mg Dai) vs. control, MP 25,6 mg | SG CG | 88 87 | 6.21 ± 0.73 6.11 ± 0.95 | 4.16 ± 0.99 4.12 ± 0.88 | 1.55 ± 0.41 1.53 ± 0.34 | 1.36 ± 0.72 1.25 ± 0.59 | 4 |

| Teede [79] 2005 Australia | Parallel groups 3-day run-in/ 3-month follow-up | Age 59.5 ± 4.5, ysm N/A, BMI 25.9 ± 5.4, healthy | SP 40 g, IC 118 mg (54 mg Gen, 3.6 mg Gly, 26 mg Dai) vs. control, CP 40 g | SG CG | 19 21 | 6.2 ± 1.30 5.8 ± 0.92 | 4.0 ± 0.87 3.6 ± 0,92 | 1.6 ± 0.43 1.6 ± 0.46 | 1.0 ± 0.48 1.0 ± 0.63 | 3 |

| Allen [66] 2007 United States | Parallel groups 4-week run-in/ 12-week follow-up | Age 56.8 ± 5.6, ysm 9.4 ± 8.3 y, BMI 27.9 ± 4.7, hypercholesterolemia | SP 20 g, IC 160 mg (~96 mg Agl) vs. control, MP 20 g | SG CG | 93 98 | 5.80 ± 0.68 5.71 ± 0.64 | 3.67 ± 0.68 3.60 ± 0.57 | 1.56 ± 0,37 1.52 ± 0.31 | 1.25 ± 0.51 1.28 ± 0.60 | 5 |

| Maesta [77] 2007 Brazil | Parallel group 16-week follow-up | Age 61.3 ± 5,2, ysm 10.7 ± 4.9 y, BMI 27.2 ± 5.3 healthy | SP 25 g, IAE 50 mg (32 mg Gen, 15 mg Dai, 3 mg Gly) vs. placebo, maltodextrine | SG CG | 10 11 | 5.95 ± 0.71 5,76 ± 0.98 | 3.71 ± 0.72 3.56 ± 0.70 | 1.62 ± 0.34 1.32 ± 0.25 | 1.36 ± 0.52 1.95 ± 0.71 | 5 |

| Basaria [67] 2009 United States | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 55.7 ± 1.3, ysm 5.7 ± 0.9, BMI 26.1 ± 0.8, healthy | SP 20 g, IC 160 mg (IAE: 64 mg Gen, 63 mg Dai, 34 mg Gly) vs. control, MP 20 g | SG CG | 38 46 | 5.48 ± 0.14 5.69 ± 0.85 | 3.15 ± 0.75 3.21 ± 0.74 | 1.88 ± 0.46 2.02 0.46 | 1.03 ± 0.58 0.99 ± 0.46 | 4 |

| Campbell [69] 2010 United States | Parallel groups 12-month follow-up | Age 54.7 ± 5.5, ysm 5.5 ± 5.0, BMI 27.9 ± 5.9, hypercholesterolemia | SP 25 g, 60 mg IF vs. control, CP 25 g | SG CG | 35 27 | 5.97 ± 0,93 6.15 ± 0.91 | 3.88 ± 0.90 3.95 ± 0.87 | 1.47 ± 0.38 1.50 ± 0.36 | 1.34 ± 0.70 1.48 ± 0.67 | 4 |

| Jassi [74] 2010 India | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 51.1 ± 8.6, ysm 2.3 ± 1.2, BMI 23.4 ± 2.7, healthy | SP 30 g, IF 60 mg vs. control, CP 30 g | SG CG | 25 25 | 4.96 ± 0.36 4.69 ± 0.71 | 3.09 ± 0.37 2.83 ± 0.76 | 1.06 ± 0.15 1.06 ± 0.16 | 1.76 ± 0.28 1.76 ± 0.17 | 4 |

| Liu [76] 2012 Hong Kong SAR | Parallel groups 2-week run-in/ 3-month follow-up | Age 56.3 ± 4.3, ysm 5.9 ± 5.4, BMI 24.4 ± 3.6, prediabetes | SP 15 g, IAE 100 mg (59 mg Gen,4 mg Gly, 35 mg Dai) vs. control, MP 15 g | SG CG | 60 60 | 5.83 ± 0.94 5.63 ± 0.93 | 3.94 ± 0.67 3.81 ± 0.88 | 1.66 ± 0.31 1.65 ± 0.30 | 1.35 ± 1.19 1.30 ± 0.70 | 5 |

| B.2. Soy isoflavones preparations | ||||||||||

| Dewell [85] 2002 USA | Parallel groups 2-month follow-up | Age 69.5 ± 4.2 y, ysm N/A, BMI 25.0 ± 4,2, moderate hypercholesterolemia | IC 150 mg (90 mg Agl: 45 mg Gen, 55% Dai and Gly) vs. placebo | SG CG | 20 16 | 6.8 ± 0.9 6.3 ± 2.0 | N/A N/A | 1.2 ± 0.5 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.5 1.3 ± 0.8 | 4 |

| Colacurci [93] 2005 Italy | Parallel groups 6-month follow-up | Age 55.1 ± 38 y, ysm 4.9 ± 0.6, BMI 25.9 ± 1.8, healthy | IAE 60 mg (30 mg Gen, 30 mg Dai) vs. placebo | SG CG | 29 28 | NR NR | 3.7 ± 0.3 3.6 ± 0.4 | 1.06 ± 0.5 1.05 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 1.6 ± 0.8 | 4 |

| Garrido [87] 2006 Chile | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 55.5 ± 4.0 y, ysm N/A, BMI 26.9 ± 2.3, healthy | IAE ~100 mg (46.8 mg Gen, 48.2 mg Dai) vs. placebo | SG CG | 15 14 | 5.5 ± 1.0 4.8 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.4 2.9 ± 03 | 1.4 ± 0.3 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.2 1.4 ± 0.2 | 3 |

| Wu [92] 2006 Japan | Parallel group 6-month follow-up | Age 54.4 ± 2.9 y, ysm N/A, BMI 21.1 ± 2.4, healthy | IC 75 mg (47 mg Agl: 38.3 mg Dai, 8.6 mg, 1 mg Gly) vs. placebo | SG CG | 25 29 | 5.90 ± 0.76 5.88 ± 0.86 | 3.52 ± 0.72 3.59 ± 0.76 | 1.92 ± 0.47 1.85 ± 0.38 | 0.95 ± 0.43 1.16 ± 0.53 | 3 |

| Nahas [90] 2007 Brazil | Parallel groups 4-week run-in 4-month follow-up | Age 55.7 ± 6.8, ysm 6.9 ± 4.5, BMI 29.1 ± 5.0, obesity | IC 100 mg (50% Gen, 35% Dai), vs. placebo | SG CG | 38 36 | 5.56 ± 0.92 5.37 ± 0.97 | 3.47 ± 0.82 3.26 ± 0.82 | 1.29 ± 0.27 1.35 ± 0.34 | 1.73 ± 0.74 1.67 ± 0.89 | 3 |

| Ho [88] 2007 China | Parallel groups 6-month follow up | Age 54.2 ± 3.1, ysm 4,1 ± 2.4, BMI 24.1 ± 3.6, healthy | a. IAE 80 mg, b. IAE 40 mg (46.4% Dai, 38.8 Gly, 14.7% Gen) vs. placebo | SG 80 SG 40 CG | 67 68 68 | 5.86 ± 0.83 5.83 ± 0.84 5.93 ± 0.89 | 3.19 ± 0.74 3.23 ± 0.68 3.25 ± 0.73 | 1.89 ± 0.41 1.80 ± 0.39 1.86 ± 0.42 | 1.13 ± 0.56 1.32 ± 0.93 1.29 ± 0.96 | 4 |

| Aubertin-Leheudre [81] 2008 Canada | Parallel groups 6-month follow-up | Age 57.4 ± 5.4 y, ysm 8.6 ± 7.5, BMI 32.0 ± 12.5, obesity | IAE 70 mg (44 mg Dai, 16 mg Gly, 10 mg Gen) vs. placebo | SG CG | 21 18 | 5.41 ± 0.88 5.33 ± 0.83 | 3.17 ± 0.81 3.17 ± 0.78 | 1.55 ± 0.49 1.45 ± 0.37 | 1.51 ± 0.69 1.52 ± 0.69 | 4 |

| Özturk Turhan [91] 2009 Turkey | Parallel groups 6-month follow-up | Age 51.5 ± 5.1; ysm 3.6 ± 1.7, BMI 27.1 ± 3.1 | IAE 40 mg (29.8 mg Gen, 7.8 mg Dai, 2.4 mg Gly) vs. placebo | SG CG | 45 45 | 6.82 ± 0.96 6.30 ± 0.76 | 4.25 ± 0.73 4.01 ± 0.65 | 1.06 ± 0.15 1.06 ± 0.16 | 1.76 ± 0.28 1.76 ± 0.17 | 4 |

| Choquette [84] 2011 Canada | Parallel groups 6-month follow-up | Age 58.5 ± 5.5 y, ysm 9.0 ± 7.0, BMI 30.1 ± 2.7, obesity | IAE 70 mg (44 mg Dai, 16 mg Gly, 10 mg Gen) vs. placebo | SG CG | 23 22 | 5.40 ± 0.80 5.58 ± 0.86 | 3.34 ± 0.75 3.34 ± 0.81 | 1.49 ± 0.34 1.37 ± 0.32 | 1.47 ± 0.67 1.44 ± 0.73 | 5 |

| Kim [89] 2013 Republic of Korea | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 53.6 ± 3.4 y, ysm 3.6 ± 2,4, BMI 23.3 ± 2.5, healthy | IC 70 mg (Glyc: 38 mg glycitin 20 mg daidzin, 12 mg genistin) vs. placebo | SG CG | 42 43 | 5.13 ± 0.85 5.48 ± 1.03 | 2.97 ± 0.70 3.25 ± 0.92 | 1.48 ± 0.36 1.52 ± 0.37 | 1.26 ± 0.72 1.27 ± 0.66 | 4 |

| Chilibec [83] 2013 Canada | Parallel groups 24-month follow-up | Age 56.6 ± 68 y, yms N/A, BMI 27.1 ± 4.1, healthy | IC 165 mg (150 mg Agl: Gen, Da and Gly in ratio of 1:1:0.5) vs. placebo | SG CG | 72 73 | 5.87 ± 0.96 5.76 ± 0.91 | 3.68 ± 0.91 3.59 ± 0.89 | 1.58 ± 0.41 1.52 ± 0.44 | 1.41 ± 1.03 1.43 ± 0.79 | 4 |

| Engelbert [86] 2016 Germany | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 59.5 ± 6.03 y, yms ≥ 1 y, BMI 25.2 ± 3.8, healthy | IAE 117.4 mg (49.7% Gen, 41.4% Dai, 9.0% Gly) vs. placebo, maltodextrin | SG CG | 85 85 | 5.88 ± 0.89 5.80 ± 0.91 | 3.78 ± 0.89 3.67 ± 0.85 | 1.95 ± 0.44 1.99 ± 0.45 | 1.04 ± 0.39 1.04 ± 0.38 | 4 |

| Barrasa [82] 2018 Chile | Parallel groups 1-week run-in 3-month follow-up | Age 64.7 ± 4.6 y, ysm N/A, BMI 27.6 ± 0.9, healthy | IAE 100 mg (52 mg Gen, 40 mg Dai, 8 mg Gly) vs. placebo | SG CG | 20 15 | 5.13 ± 0.68 4.87 ± 0.62 | 3.10 ± 0.94 2.97 ± 0.50 | 1.30 ± 0.43 1.18 ± 0.38 | 1.53 ± 0.39 1.54 ± 0.36 | 4 |

| C. Red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) | ||||||||||

| Hale [96] 2001 Australia | Parallel groups 3-month follow-up | Age 47.2 ± 2.4 y, yms N/A, BMI 26.7 ± 4.6, healthy | IAE 50 mg (big amount of Bio and small amount of For (no data)) vs. placebo | RCG CG | 14 14 | 4.64 ± 0.78 4.19 ± 0.85 | 2.89 ± 0.61 2.49 ± 0.73 | 1.29 ± 0.24 1.34 ± 0.43 | 1.46 ± 0.67 1.61 ± 1.04 | 4 |

| Atkinson [94] 2004 United Kingdom | Parallel groups 12-month follow-up | Age 52.2 ± 4.8 y, yms N/A, BMI 25.3 ± 3.7, healthy | IAE 40 mg (24.5 mg Bio, 8.0 mg For, 1 mg Gen, 1 mg Dai) vs. placebo | RCG CG | 77 86 | 6.34 ± 1.19 6.08 ± 1.04 | 4.21 ± 0.94 3.88 ± 1.00 | 1.61 ± 0.41 1.66 ± 0.48 | 1.24 ± 0.71 1.19 ± 0.66 | 3 |

| Schult [100] 2004 USA | Parallel groups 2-week run-in 12-week follow-up | Age 52.3 ± 3.1 y, yms 3.2 ± 4.5, BMI 26.1 ± 4.9, healthy | IAE 82 mg (49 mg Bio, 14 mg For, 8 mg Gen, 7 mg Dai). IAE 57 mg (44.6 mg For, 5.8 mg Bio, 0.8 mg Dai, 0.8 mg Gly) vs. placebo | RCG 82 RCG 57 CG | 81 81 83 | 5.76 ± 0.92 5.77 ± 1.01 5.72 ± 0.83 | 3.77 ± 1.01 3.81 ± 1.14 3.72 ± 0.79 | 1.36 ± 0.37 1.34 ± 0.34 1.38 ± 0.40 | 1.32 ± 0.65 1.31 ± 0.77 1.22 ± 0.56 | 4 |

| Hilgado [97] 2005 Ecuador | Cross-over 90-day active phase 7-day washout | Age 51.3 ± 3.5 y, yms ≥ 1 y, BMI 26.1 ± 3.9, healthy | IAE 80 mg (49 mg Bio, 16 mg For, 8 mg Gen, 7 mg Dai) vs. placebo | RCG CG | 53 53 | 5.79 ± 0.97 5.79 ± 0.97 | 3.80 ± 0.77 3.80 ± 0.77 | 1.03 ± 0.30 1.03 ± 0.30 | 2.28 ± 0.89 2.28 ± 0.89 | 4 |

| Clifton-Bligh [95] 2015 Australia | Parallel groups 1-month run-in 12-month follow-up | Age 54.4 ± 3.9 y, yms ≥ 1 y, BMI 24.8 ± 4.3, healthy | IAE 57 mg (44.6 mg For, 5.8 mg Bio, 1.9 mg Dai, 0.8 mg Gen, 0.8 Gly) vs. placebo | RCG CG | 56 47 | 5.91 ± 1.05 5.80 ± 0.88 | 3.68 ± 0.94 3.43 ± 0.86 | 1.67 ± 0.35 1.82 ± 0.49 | 1.33 ± 0.60 1.11 ± 0.63 | 5 |

| Lambert [98] 2017 Denmark | Parallel groups 12-week follow-up | Age 52.5 ± 3.5 y, yms N/A, BMI 25.7 ± 4.3 healthy | IEA 33.8 mg (19 mg For, 9 mg Bio, 2.2 mg Gen, 1.6 Dai) vs. placebo | RCG CG | 30 29 | 5.38 ± 0.19 5.63 ± 0.10 | 3.36 ± 0.16 3.40 ± 0.17 | 1.76 ± 0.15 1.73 ± 0.10 | 1.20 ± 0.09 1.18 ± 0.10 | 6 |

| Lambert [99] 2017 Denmark | Parallel groups 12-month follow-up | Age 61.8 ± 6.4 y, amenorrhea ≥12 months, BMI 25.6 ± 4.5, healthy | IEA 55.8 mg (31.4 mg For, 14.9 mg Bio, 6.9 mg Gen, 2.6 mg Dai) vs. placebo | RCG CG | 38 40 | 5.54 ± 0.86 5.64 ± 1.01 | 3.28 ± 0.86 3.37 ± 0.89 | 1.81 ± 0.43 1.82 ± 0.51 | 1.16 ± 0.37 1.38 ± 0.63 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Błaszczuk, A.; Barańska, A.; Kanadys, W.; Malm, M.; Jach, M.E.; Religioni, U.; Wróbel, R.; Herda, J.; Polz-Dacewicz, M. Role of Phytoestrogen-Rich Bioactive Substances (Linum usitatissimum L., Glycine max L., Trifolium pratense L.) in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122467

Błaszczuk A, Barańska A, Kanadys W, Malm M, Jach ME, Religioni U, Wróbel R, Herda J, Polz-Dacewicz M. Role of Phytoestrogen-Rich Bioactive Substances (Linum usitatissimum L., Glycine max L., Trifolium pratense L.) in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(12):2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122467

Chicago/Turabian StyleBłaszczuk, Agata, Agnieszka Barańska, Wiesław Kanadys, Maria Malm, Monika Elżbieta Jach, Urszula Religioni, Rafał Wróbel, Jolanta Herda, and Małgorzata Polz-Dacewicz. 2022. "Role of Phytoestrogen-Rich Bioactive Substances (Linum usitatissimum L., Glycine max L., Trifolium pratense L.) in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 14, no. 12: 2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122467

APA StyleBłaszczuk, A., Barańska, A., Kanadys, W., Malm, M., Jach, M. E., Religioni, U., Wróbel, R., Herda, J., & Polz-Dacewicz, M. (2022). Role of Phytoestrogen-Rich Bioactive Substances (Linum usitatissimum L., Glycine max L., Trifolium pratense L.) in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(12), 2467. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122467