Evaluating Mediterranean Diet-Adherent, Healthy and Allergen-Free Meals Offered in Tarragona Province Restaurants (Catalonia, Spain): A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

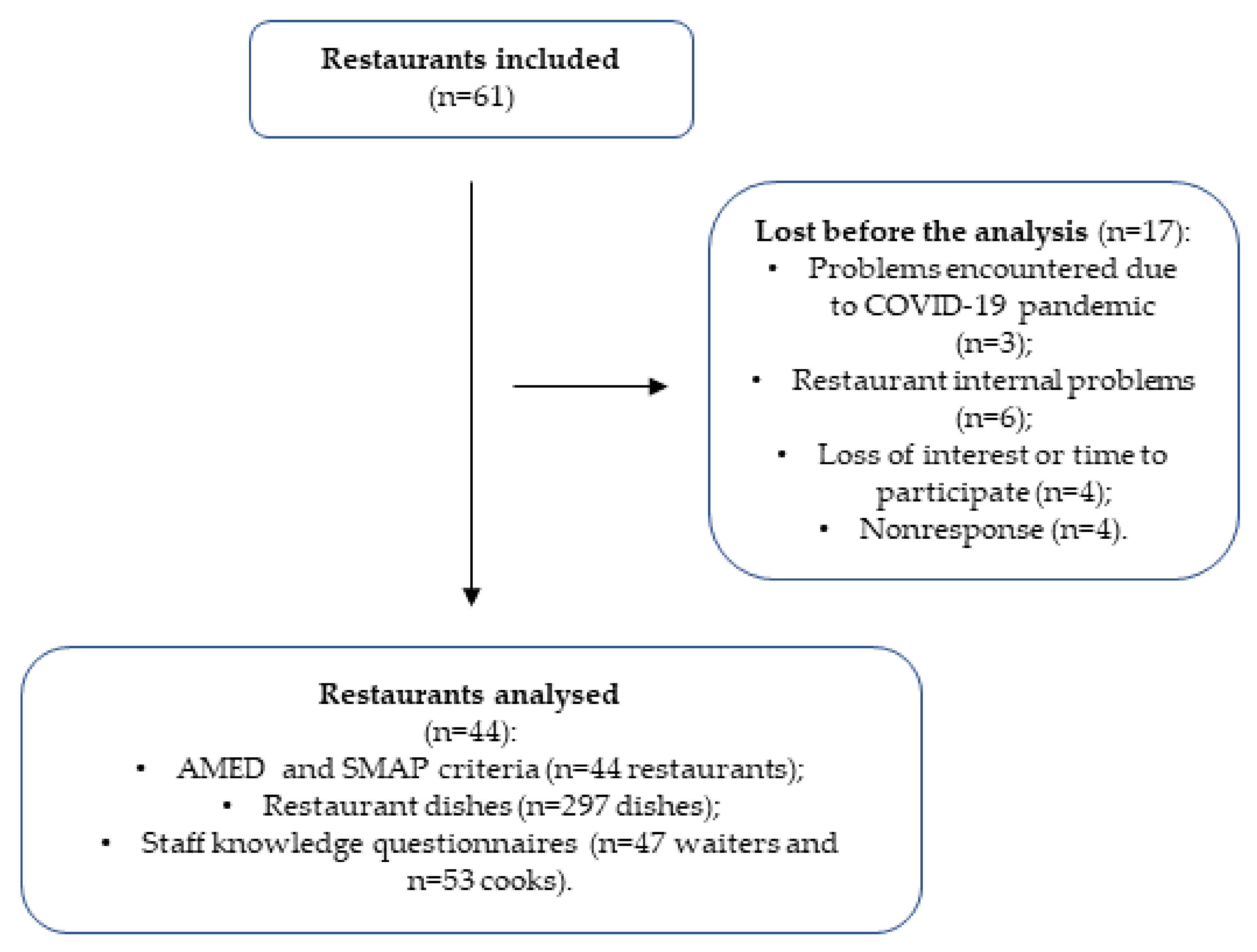

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Setting

2.3. Outcomes and Data Collection

- (1)

- number of compulsory AMed criteria, which must be fulfilled by restaurants to obtain a certification that the restaurant offers a Mediterranean diet (described below), as determined through face-to-face interviews with the restaurant owner;

- (2)

- number of SMAP criteria fulfilled by restaurants, as assessed through face-to-face interviews with the restaurant owner to determine the potential for obtaining the corresponding certification;

- (3)

- number of dishes per restaurant with a green rating in the traffic light rating system on the Healthy Meals app for the evaluated nutrients (energy, carbohydrates, sugar, fat, saturated fat, protein, sodium and fibre), which indicates good nutritional quality, according to the analysis of the recipes of the dishes, including the ingredients, weights and cooking details;

- (4)

- nutrient content of the restaurants’ meals (kcal of energy; grams of carbohydrates, sugar, fat, saturated fat, protein and fibre; micrograms of sodium), assessed by the Healthy Meals web-based app, which was designed and developed by researchers according to the framework of the PECT-TurisTIC en Familia project;

- (5)

- allergen content assessment, identified through the Healthy Meals web-based app;

- (6)

- adequacy of vegetarian and vegan dishes, also evaluated through the Healthy Meals app.

2.3.1. AMed Criteria

2.3.2. Gluten Management (SMAP) Criteria

2.3.3. Nutritional Content Assessment of Restaurant-Offered Dishes

2.3.4. Allergen Assessment

2.3.5. Adequacy for Vegetarian and Vegan Diet

2.3.6. Restaurant Staff Knowledge about the Mediterranean Diet and Food Allergens

2.4. Additional Data

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Included Restaurants

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Restaurant Owners and Their Employees

3.3. AMed Criteria

3.4. SMAP Criteria

3.5. Traffic Light and Nutritional Content Assessment of the Restaurants’ Offered Dishes

3.6. Allergen Content Assessment and Vegetarian and Vegan Dish Adequacy

3.7. Knowledge of Restaurant Staff about the Mediterranean Diet and Food Allergens

3.8. Additional Data

Restaurants’ Purchased Foods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Adams, J.; Goffe, L.; Brown, T.; Lake, A.A.; Summerbell, C.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A.J. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008-12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Available online: https://empresa.dinamig.cat/media/sites/2/2018/07/Estudi-de-la-Restauraci%C3%B3-a-Catalunya.-H%C3%A0bits-de-comportament-i-tend%C3%A8ncies-pdf (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- Orfanos, P.; Naska, A.; Rodrigues, S.; Lopes, C.; Freisling, H.; Rohrmann, S.; Sieri, S.; Elmadfa, I.; Lachat, C.; Gedrich, K.; et al. Eating at restaurants, at work or at home. Is there a difference: A study among adults of 11 European countries in the context of the HECTOR∗ project. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obbagy, J.E.; Essery, E.V.; USDA. The Food Environment, Eating Out, and Body Weight: A Review of the Evidence. Nutr. Insight 2012, 49, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Myhre, J.B.; Loken, E.B.; Wandel, M.; Andersen, L.F. Eating location is associated with the nutritional quality of the diet in Norwegian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Snchez-Villegas, A.; Marti, A.; Martnez, J.A.; Martnez-González, M.A. A prospective study of eating away-from-home meals and weight gain in a Mediterranean population: The SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, M.K.; Kim, T.Y.; Yoon, J.S. Does frequent eating out cause undesirable food choices? Association of food away from home with food consumption frequencies and obesity among Korean housewives. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2011, 50, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Briend, A.; Drewnowski, A. Energy-dense diets are associated with lower diet costs: A community study of French adults. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Creel, J.S.; Sharkey, J.R.; McIntosh, A.; Anding, J.; Huber, J.C. Availability of healthier options in traditional and nontraditional rural fast-food outlets. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- An, R. Effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: A review of field experiments. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lorenzen, C.L. Effective nutrition labeling of restaurant menu and pricing of healthy menu. J. Foodserv. 2008, 19, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothwehr, F.; Snetselaar, L.; Dawson, J.D.; Hradek, C.; Sepulveda, M. Healthy Option Preferences of Rural Restaurant Customers. Health Promot. Pract. 2010, 11, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuster, M.; Handley, M.A.; Alam, T.; Fullington, L.A.; Elbel, B.; Ray, K.; Huang, T.T.K. Facilitating healthier eating at restaurants: A multidisciplinary scoping review comparing strategies, barriers, motivators, and outcomes by restaurant type and initiator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versluis, A.; Knulst, A.C.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Michelsen, A.; Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L.; van Os-Medendorp, H. Frequency, severity and causes of unexpected allergic reactions to food: A systematic literature review. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, D.K.; Kagan, R.S.; Turnbull, E.; Joseph, L.; St. Pierre, Y.; Dufresne, C.; Gray-Donald, K.; Clarke, A.E. Lunch Guidelines Are Effective in Reducing Peanut Substances in Primary School Classrooms in Montreal, Canada. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Parliment and the Council of the European Union Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, 18–63. [CrossRef]

- Begen, F.M.; Barnett, J.; Payne, R.; Gowland, M.H.; DunnGalvin, A.; Lucas, J.S. Eating out with a food allergy in the UK: Change in the eating out practices of consumers with food allergy following introduction of allergen information legislation. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, L.E.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Gary, C.E.; Fierstein, J.L.; Equi, A.; Kussmaul, C.; Dallal, G.E.; Roberts, S.B. The energy content of restaurant foods without stated calorie information. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theis, D.R.Z.; Adams, J. Differences in energy and nutritional content of menu items served by popular UK chain restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.A.; Weippert, M.V.; Dickinson, K.M.; Scourboutakos, M.J.; L’Abbé, M.R. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Calories and Nutrients of Concern in Canadian Chain Restaurant Menu Items in 2016. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, e149–e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatli, M.; Akoğlu, A. Food Allergy Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Restaurant Employees in Istanbul, Turkey. Sidas Medya 2020, 18, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loerbroks, A.; Tolksdorf, S.J.; Wagenmann, M.; Smith, H. Food allergy knowledge, attitudes and their determinants among restaurant staff: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.; Albardiaz, R.; Frew, A.J.; Smith, H. Restaurant staff’s knowledge of anaphylaxis and dietary care of people with allergies. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.E.; Sena, E.; Cuesta, M.A.; Granell, J.D.; Valiente, J.; Alvarez-Ortí, M. Evaluation of potential and real quality of virgin olive oil from “campos de Hellín” (Albacete, Spain). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2013, 90, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre-Robles, A.; Rivas, A.; Lorenzo-Tovar, M.L.; Monteagudo, C.; Mariscal-Arcas, M.; Olea-Serrano, F. Estimation of the intake of phenol compounds from virgin olive oil of a population from southern Spain. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckland, G.; Mayén, A.L.; Agudo, A.; Travier, N.; Navarro, C.; Huerta, J.M.; Chirlaque, M.D.; Barricarte, A.; Ardanaz, E.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; et al. Olive oil intake and mortality within the Spanish population (EPIC-Spain). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaforio, J.J.; Visioli, F.; Alarcón-De-la-lastra, C.; Castañer, O.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Fitó, M.; Hernández, A.F.; Huertas, J.R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Menendez, J.A.; et al. Virgin olive oil and health: Summary of the iii international conference on virgin olive oil and health consensus report, JAEN (Spain) 2018. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki-Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/ (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/about-site/background (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gencat-Instituto de Estadística de Cataluña Población Empadronada. Por Tamaño del Municipio. Comarcas, ámbitos y Provincias. Population Registered. By Size of Municipality. Districts, Areas and Provinces. 2020. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=aec&n=248&lang=es (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Tripadvisor. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.es/ (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya. Alimentación Mediterrània. Mediterranean Diet; ASPCAT: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; Available online: http://www.amed.cat/home.php (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Associació Celíacs de Catalunya SMAP Criteria. Gluten Management. Available online: https://www.celiacscatalunya.org/es/index.php (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- RedBedca. AESAN Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos-BEDCA. Spanish Database of Food Composition-BEDCA. Available online: https://www.bedca.net/ (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Mcgraw-Hill. Tablas De Composicion De Alimentos Del Cesnid. In Cesnid Food Composition Tables; Interamericana de España: Madrid, Spain, 2003; ISBN 9788448605902. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú, J.M. Tabla De Composición De Alimentos. In Food Composition Table, 4th ed.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2003; ISBN 978-84-3383-050-3. [Google Scholar]

- Favier, J.C.; Ireland-Ripert, J.; Toque, C.; Feinberg, M. Répertoire général des aliments: Table de composition. In General Food Directory: Composition Table; Technique & Documentation; FRA: Paris, France, 1995; ISBN 2-85206-921-0. [Google Scholar]

- Moreiras, O.; Carbajal, Á.; Cabrera, L.; Cuadrado, C. Tablas de composición de alimentos. In Food Composition Tables, 16th ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2013; ISBN 8436815718. [Google Scholar]

- Food Standards Agency; Department of Health; Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales Governments. Guide to Creating a Front of Pack (FoP) Nutrition Label for Pre-Packed Products Sold through Retail Outlets; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/front-of-pack-nutrition-labelling-guidance (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Federación Española de Industrias de Alimentación y Bebidas (FIAB); Confederación Europea de Industrias de Alimentación y Bebidas (CIAA). Recomendación CIAA para un esquema común de etiquetado nutricional. In CIAA Recommendation for a Common Nutrition Labeling Scheme; FIAB: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tuso, P.J.; Ismail, M.H.; Ha, B.P.; Bartolotto, C. Nutritional update for physicians: Plant-based diets. Perm. J. 2013, 17, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McAdams, B.; Deng, A.; MacLaurin, T. Food allergy knowledge, attitudes, and resources of restaurant employees. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2681–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; Rutkow, L.; Gudzune, K.A.; Cohen, J.E.; McGinty, E.E. Healthiness of US Chain Restaurant Meals in 2017. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, R.; Sidebottom, A.C.; McCool, B.; Pereira, R.F.; Sillah, A.; Boucher, J.L. Changing the restaurant food environment to improve cardiovascular health in a rural community: Implementation and evaluation of the Heart of New Ulm restaurant programme. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Mendez, C.; Garcia-Espejo, I. Eating out in Spain: Motivations, sociability and consumer contexts. Appetite 2017, 119, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, M.; Lemieux, S.; Lapointe, A.; Bédard, A.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Bégin, C.; Provencher, V.; Desroches, S. Is eating pleasure compatible with healthy eating? A qualitative study on Quebecers’ perceptions. Appetite 2018, 125, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornil, Y.; Chandon, P. Pleasure as an ally of healthy eating? Contrasting visceral and Epicurean eating pleasure and their association with portion size preferences and wellbeing. Appetite 2016, 104, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRae, M.P. Health Benefits of Dietary Whole Grains: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. J. Chiropr. Med. 2017, 16, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO/WHO. Fruit and Vegetables for Health-Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Workshop; FAO: Kobe, Japan; WHO: Kobe, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Mozaffarian, D. Global, regional and national consumption of major food groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tritt, A.; Reicks, M.; Marquart, L. Reformulation of pizza crust in restaurants may increase whole-grain intake among children. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anzman-Frasca, S.; Dawes, F.; Sliwa, S.; Dolan, P.R.; Nelson, M.E.; Washburn, K.; Economos, C.D. Healthier side dishes at restaurants: An analysis of children’s perspectives, menu content, and energy impacts. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Ruíz-López, M.D. Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, M.J.; Huitink, M.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Maaskant, A.J.; Heijnen, J. Menu-engineering in restaurants—adapting portion sizes on plates to enhance vegetable consumption: A real-life experiment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josiam, B.; Foster, C. Nutritional information on restaurant menus: Who cares and why restauranteurs should bother. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 876–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaru, B.I.; Hickstein, L.; Panesar, S.S.; Roberts, G.; Muraro, A.; Sheikh, A. Prevalence of common food allergies in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 69, 992–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovoli, F.; Masi, C.; Guidetti, E.; Negrini, G.; Paterini, P.; Bolondi, L. Clinical and diagnostic aspects of gluten related disorders. World J. Clin. Cases 2015, 3, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Šálková, D.; Hes, A. Gluten-free food—The influence of selected qualitative characteristics on consumer decision making of coeliacs in hospitality establishments. Czech. J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, K.R.; Barrett, B.B.; Howells, A.D.; Shanklin, C.W.; Pilling, V.K.; Brannon, L.A. Food Safety Training and Foodservice Employees’ Knowledge and Behavior. Food Safey Train. Foodserv. Empl. 2018, 28, 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam, M.; Wiersma, L. To what extent are restaurants prepared to respond to the needs of guests with food allergies and intolerances? Res. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 2, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, I.; Thaivalappil, A. A systematic review and meta-regression of the knowledge, practices, and training of restaurant and food service personnel toward food allergies and Celiac disease. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, M.; Shin, S.; Coppell, K.J. Awareness of coeliac disease among chefs and cooks depends on the level and place of training. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincentini, O.; Izzo, M.; Maialetti, F.; Gonnelli, E.; Neuhold, S.; Silano, M. Risk of Cross-Contact for Gluten-Free Pizzas in Shared-Production Restaurants in Relation to Oven Cooking Procedures. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studerus, D.; Hampe, E.I.L.G.; Fahrer, D.; Wilhelmi, M.; Vavricka, S.R. Cross-contamination with gluten by using kitchen utensils: Fact or fiction? J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, B.A.; Vo, L.P.; Yates, S.; Rundle, A.G.; Lebwohl, B.; Green, P.H.R. Detection of Gluten in Gluten-Free Labeled Restaurant Food: Analysis of Crowd-Sourced Data. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, I.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P.; Barros, R. Food allergy: Practical approach on education and accidental exposure prevention. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 48, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Medina, A. Spain Spanish Consumers Grow Interest in Free From Functional Foods; USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smart Protein Project. Plant.-Based Foods in Europe: How Big Is the Market? In The Smart Protein Plant; based Food Sector Report; Smart Protein Project: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Available online: https://smartproteinproject.eu/plant-based-food-sector-report (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Garnett, E.E.; Balmford, A.; Sandbrook, C.; Pilling, M.A.; Marteau, T.M. Impact of increasing vegetarian availability on meal selection and sales in cafeterias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 20923–20929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mcguf, L.E.; Price, R.K.; Mccaffrey, T.A.; Hall, G.; Lobo, A.; Wallace, J.M.W.; Livingstone, M.B.E. Parent and child perspectives on family out-of-home eating: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 18, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anzman-Frasca, S.; Folta, S.C.; Glenn, M.E.; Jones-Mueller, A.; Lynskey, V.M.; Patel, A.A.; Tse, L.L.; Lopez, N.V. Healthier Children’s Meals in Restaurants: An Exploratory Study to Inform Approaches That Are Acceptable Across Stakeholders. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 285–295.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.P.; Shonkoff, E.T.; Folta, S.C.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Economos, C.D. Orders of healthier adult menu items in a full-service restaurant chain with a healthier children’s menu. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavahian, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Garcia-Mantrana, I.; Collado, M.C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Barba, F.J. Health benefits of olive oil and its components: Impacts on gut microbiota antioxidant activities, and prevention of noncommunicable diseases. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition. The Amazing Twelve: 12 Recommendations for a Healthy and Sustainable Diet. 2020. Available online: https://www.barillacfn.com/en/magazine/food-and-sustainability/12-recommendations-for-a-healthy-and-sustainable-diet/ (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Morawicki, R.O.; Díaz González, D.J. Food sustainability in the context of human behavior. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2018, 91, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| N = 44% (n) | |

|---|---|

| Restaurant type: | |

| Rural | 13.6 (6) |

| Urban | 68.2 (30) |

| Coastal | 18.2 (8) |

| Restaurant offer: | |

| Daily menu | 22.7 (10) |

| Menu | 22.7 (10) |

| Daily menu + menu | 54.5 (24) |

| Location: | |

| Tarragonès | 50.0 (22) |

| Baix Camp | 38.6 (17) |

| Montsià | 7.0 (3) |

| Baix Penedès | 2.3 (1) |

| Conca de Barberà | 2.3 (1) |

| Time of restaurant activity in years 2: | 13.2 ± 18.9 |

| Frequency of menu changes: | |

| Twice a year (winter/summer) | 22.7 (10) |

| More than twice a year | 22.7 (10) |

| It is the same throughout the year | 25.0 (11) |

| Other | 22.7 (10) |

| Not answered | 6.8 (3) |

| Administration of the restaurant: | |

| The owner with his/her family | 50.0 (22) |

| The owner with recruited staff | 38.6 (17) |

| Recruited manager | 4.5 (2) |

| The owner with his family and the recruited staff | 4.5 (2) |

| Not answered | 2.3 (1) |

| Number of recruited employees 2: | 5.4 ± 4.2 |

| Type of cuisine 1: | |

| Traditional | 54.5 (24) |

| Spanish | 36.4 (16) |

| Catalan | 43.2 (19) |

| Mediterranean | 72.7 (32) |

| Author | 18.2 (8) |

| Italian | 13.6 (6) |

| Fusion | 15.9 (7) |

| Tapas | 31.8 (14) |

| Other | 11.4 (5) |

| Presence on the menu of 1: | |

| Nutritional information | 0.0 (0) |

| Traffic light labels | 0.0 (0) |

| GDAs | 0.0 (0) |

| Healthier choice indicators | 0.0 (0) |

| Colours | 6.8 (3) |

| Other (allergens, vegan/vegetarian/celiac options, typical cuisine meals, prepared with local products) | 29.5 (13) |

| Availability of a children’s menu: | |

| Yes | 29.5 (13) |

| No | 70.5 (31) |

| Availability of daily menu: | |

| Yes | 77.3 (34) |

| No | 22.7 (10) |

| Availability of a weekend menu: | |

| Yes | 56.8 (25) |

| No | 43.2 (19) |

| Total 1 (N = 144) % (n) | Owners 2 (N = 44) % (n) | Cooks 2 (N = 53) % (n) | Waiters 2 (N = 47) % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: | ||||

| Men | 60.4 (87) | 59.1 (26) | 67.9 (36) | 53.2 (25) |

| Women | 28.5 (41) | 18.2 (8) | 28.3 (15) | 38.3 (18) |

| Not answered | 11.1 (16) | 22.7 (10) | 3.8 (2) | 8.5 (4) |

| Education degree: | ||||

| Uneducated | 1.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 1.9 (1) | 2.1 (1) |

| First grade studies | 21.5 (31) | 25.0 (11) | 18.9 (10) | 21.3 (10) |

| Second grade studies | 57.6 (83) | 52.3 (23) | 60.4 (32) | 59.6 (28) |

| Third grade studies | 16.7 (24) | 18.2 (8) | 18.9 (10) | 12.8 (6) |

| Not answered | 2.8 (4) | 4.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (2) |

| Experience of the restaurant owners in the catering sector 3: | ||||

| Years | 18.0 ± 10.6 |

| N = 44 % (n) | |

|---|---|

| AMed Compulsory criteria: | |

| (1) olive oil for dressing, and olive oil or high oleic sunflower for cooking | 75.0 (33) |

| (2) 25% of the first course offerings are vegetables and/or legumes | 70.5 (31) |

| (3) presence of whole-grain products | 34.1 (15) |

| (4) 50% of the second course offerings based on fish, seafood and lean meat | 59.1 (26) |

| (5) 50% of the dessert offerings based on fresh fruit (whole or prepared) | 2.3 (1) |

| (6) offer of dairy desserts without added sugar | 43.2 (19) |

| (7) offer of free nonpackaged drinking water | 31.8 (14) |

| (8) wine, beer and cava are measured in glasses or individual units | 100 (44) |

| (9) have culinary preparations that do not require the addition of large amounts of fat, and culinary techniques that use little or no fat are used | 93.2 (41) |

| Number of total AMed compulsory criteria fulfilled per restaurant (mean ± SD) 1: | 5.1 ± 1.6 |

| AMed Optional criteria: | |

| (1) prioritize fresh seasonal and local foods | 100 (44) |

| (2) include proposals of the traditional and local cuisine | 95.5 (42) |

| (3) offer virgin olive oil at tables | 93.2 (41) |

| (4) prioritize side dishes of vegetables and legumes | 84.1 (37) |

| (5) offer the most symbolic recipes of the restaurant that accomplish the AMed criteria to their customers | 11.4 (5) |

| (6) offer the option of unique dishes or medium portions | 79.5 (35) |

| (7) offer options with no added salt | 88.6 (39) |

| (8) disseminate information about leisure activities in the nearby environment | 95.5 (42) |

| Number of total optional criteria fulfilled per restaurant (mean ±SD) 2: | 6.5 ± 0.9 |

| Number of 17 total AMed criteria fulfilled per restaurant (mean ±SD) 3: | 11.5 ± 2.1 |

| N = 44 %(n) | |

|---|---|

| (1) working with suppliers who guarantee their products do not contain gluten, on labels or data sheets | 75.0 (33) |

| (2) store gluten-free products separately from products containing gluten in closets, freezers or refrigerators | 77.3 (34) |

| (3) transfer to hermetically closed containers after opening, and identify the content | 86.4 (38) |

| (4) keep flours and breadcrumbs containing gluten tightly closed and store them away from other food products | 70.5 (31) |

| (5) use different or non-cross-contaminated kitchen tools for gluten-free food preparation | 95.5 (42) |

| (6) be provided of equipment for the exclusive use of gluten-free food preparation (fryers, ovens, microwaves, toasters, sandwich makers, pasta makers) | 38.6 (17) |

| (7) preparation of gluten-free plates before the other food preparation | 81.8 (36) |

| (8) have a differentiated area within the kitchen for the preparation of gluten-free food, or a good working protocol | 68.2 (30) |

| (9) cleaning of the food preparation area before starting to work | 97.7 (43) |

| (10) cleaning of the hands before starting the preparation of all the necessary ingredients | 97.7 (43) |

| (11) be provided of a clean apron, if you work with flours or products that may leave gluten traces on the clothes | 54.5 (24) |

| (12) dispose of closed salt shakers and spice boxes, or use a teaspoon to pick up the salt as long as hands will be not placed inside | 45.5 (20) |

| (13) do not use kitchen cloths and wooden tools, which are materials that can retain traces of gluten | 29.5 (13) |

| (14) do not reuse oil, cooking water or broths when gluten products have been cooked, and do not share spreads foods | 86.4 (38) |

| (15) serve gluten-free food in dishes of different colours or easy to identify (e.g., flags), and cover up until the moment of service | 72.7 (32) |

| (16) re-prepare gluten-free dishes if a potential contamination occurs with a gluten-containing product | 95.5 (42) |

| (17) place on the tables bottles of oil and vinegar, sauces and baskets for exclusive use, or single-dose portions | 18.2 (8) |

| (18) cleaning of the waiter’s hands before the serving of the gluten-free dishes, to be taken | 97.7 (43) |

| Number of total criteria fulfilled per restaurant (mean ± SD) 1: | 12.9 ± 2.8 |

| Number of Green-Light Dishes per Nutrient and Type of Plate 1: | ||||

| Total (n = 297) % (n) | Starters (n = 119) % (n) | Main dishes (n = 138) % (n) | Desserts (n = 40) % (n) | |

| Energy | 7.7 (23) | 10.1 (12) | 3.6 (5) | 15.0 (6) |

| Carbohydrates | 47.1 (140) | 55.5 (66) | 45.7 (63) | 27.5 (11) |

| Sugar | 59.9 (178) | 63.0 (75) | 73.9 (102) | 2.5 (1) |

| Protein | 10.1 (30) | 14.3 (17) | 1.4 (2) | 27.5 (11) |

| Total fat | 6.1 (18) | 5.9 (7) | 1.4 (2) | 22.5 (9) |

| Saturated fat | 14.8 (44) | 19.3 (23) | 9.4 (13) | 20.0 (8) |

| Sodium | 18.2 (54) | 13.4 (16) | 5.8 (8) | 75.0 (30) |

| Fibre | 25.9 (77) | 27.7 (33) | 26.1 (36) | 20.0 (8) |

| Nutrient content of the restaurant dishes 2: | ||||

| Total (n = 297) Mean ± SD | Starters (n = 119) Mean ± SD | Main dishes (n = 138) Mean ± SD | Desserts (n = 40) Mean ± SD | |

| Energy (Kcal) | 490.3 ± 310.2 | 442.5 ± 290.8 | 566.3 ± 319.3 | 368.9 ± 271.4 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 27.7 ± 26.5 | 26.6 ± 28.7 | 25.5 ± 23.8 | 38.7 ± 26.4 |

| Sugar (g) | 10.0 ± 13.2 | 6.8 ± 6.8 | 6.6 ± 7.4 | 31.3 ± 21.4 |

| Protein (g) | 25.5 ± 21.1 | 19.7 ± 17.3 | 35.5 ± 21.5 | 8.5 ± 10.1 |

| Total fat (g) | 30.2 ± 24.3 | 27.5 ± 21.6 | 35.7 ± 26.8 | 19.4 ± 17.6 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 8.5 ± 8.3 | 7.7 ± 8.8 | 8.8 ± 7.6 | 10.2 ± 9.4 |

| Sodium (mg) | 950.4 ± 814.4 | 1030.5 ± 836.8 | 1107.7 ± 778.0 | 169.6 ± 237.9 |

| Fibre (g) | 3.8 ± 4.0 | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 4.0 ± 4.4 | 2.2 ± 3.1 |

| Total 1 (n = 297) % (n) | Starters 1,2 (n = 119) % (n) | Main dishes 1,2 (n = 138) % (n) | Desserts 1,2 (n = 40) % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allergen-free 3 | 9.8 (29) | 12.6 (15) | 8.0 (11) | 7.5 (3) |

| Gluten-free 3 | 47.8 (142) | 53.8 (64) | 44.2 (61) | 42.5 (17) |

| Vegetarian 4 | 26.9 (80) | 36.1 (43) * | 2.2 (3) * | 85.0 (34) * |

| Vegan 4 | 9.8 (29) | 19.3 (23) * | 0.7 (1) * | 12.5 (5) |

| Mediterranean Diet Knowledge 1: | Total Staff 2 (Mean ± SD) | Waiters (Mean ± SD) | Cooks (Mean ± SD) | p-Value 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identification of foods adhering to the Mediterranean diet | 7.9 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 0.94 | |

| 2. Identification of healthy food | 6.8 ± 1.2 | |||

| 3. Identification of the AMed compulsory criteria | 7.7 ± 1.7 | |||

| Total score about Mediterranean diet 1 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 7.9 ± 1.7 | 6.9 ± 1.7 | 0.003 * |

| Food allergens knowledge 1: | ||||

| 1. Identification of food allergens in traditional meals | 3.2 ± 1.8 | |||

| 2. Identification of the critical points of food allergen management | 8.2 ± 1.7 | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 0.29 | |

| 3. Identification of food allergy and intolerance reactions | 8.0 ± 1.5 | 8.4 ± 1.4 | 0.55 | |

| Total score about food allergens 1 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 0.36 |

| Total score of staff knowledge 1 | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 0.03 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandracchia, F.; Llauradó, E.; Valls, R.M.; Tarro, L.; Solà, R. Evaluating Mediterranean Diet-Adherent, Healthy and Allergen-Free Meals Offered in Tarragona Province Restaurants (Catalonia, Spain): A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072464

Mandracchia F, Llauradó E, Valls RM, Tarro L, Solà R. Evaluating Mediterranean Diet-Adherent, Healthy and Allergen-Free Meals Offered in Tarragona Province Restaurants (Catalonia, Spain): A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072464

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandracchia, Floriana, Elisabet Llauradó, Rosa Maria Valls, Lucia Tarro, and Rosa Solà. 2021. "Evaluating Mediterranean Diet-Adherent, Healthy and Allergen-Free Meals Offered in Tarragona Province Restaurants (Catalonia, Spain): A Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 13, no. 7: 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072464

APA StyleMandracchia, F., Llauradó, E., Valls, R. M., Tarro, L., & Solà, R. (2021). Evaluating Mediterranean Diet-Adherent, Healthy and Allergen-Free Meals Offered in Tarragona Province Restaurants (Catalonia, Spain): A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 13(7), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072464