Strategies to Improve School Meal Consumption: A Systematic Review

Abstract

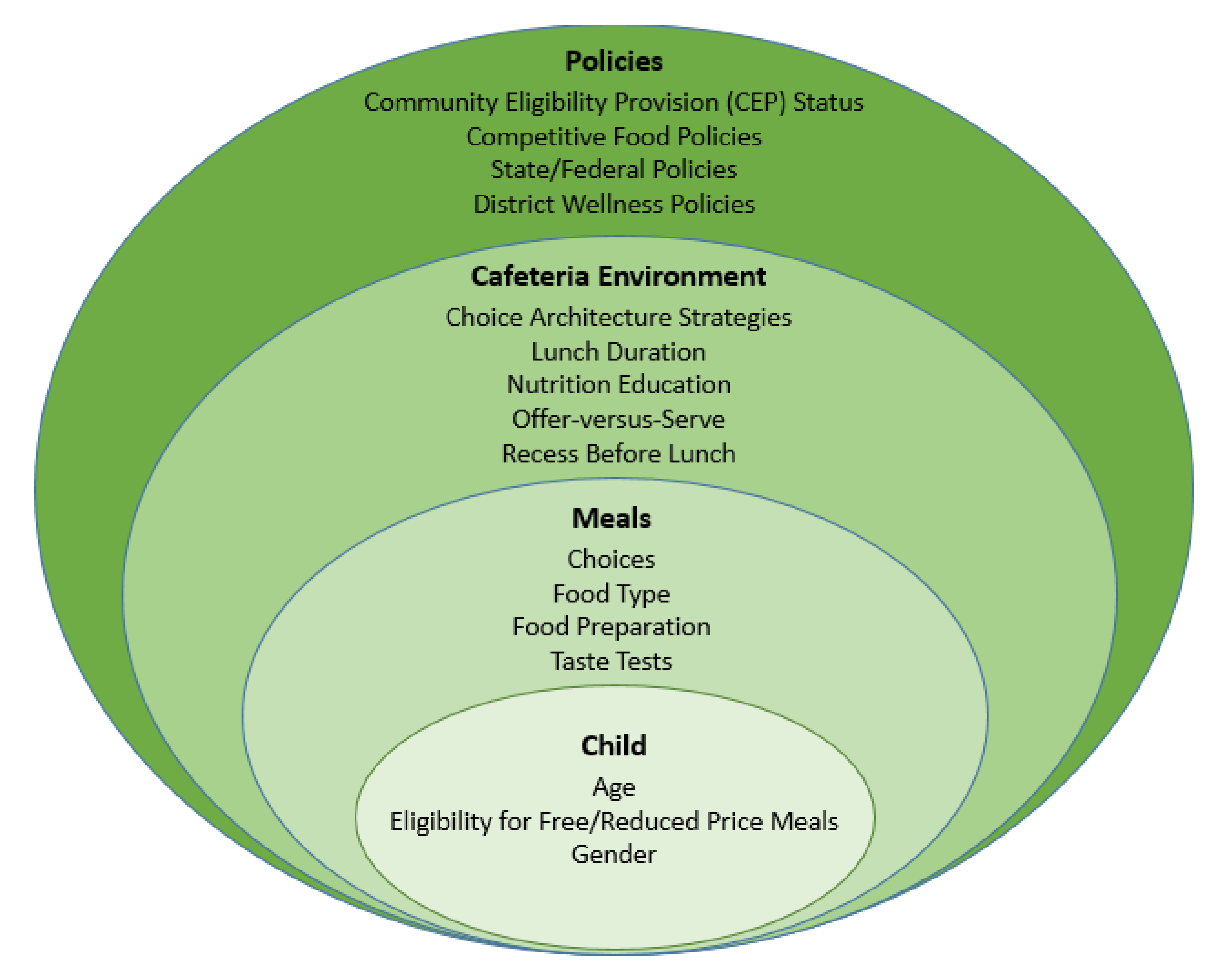

1. Introduction

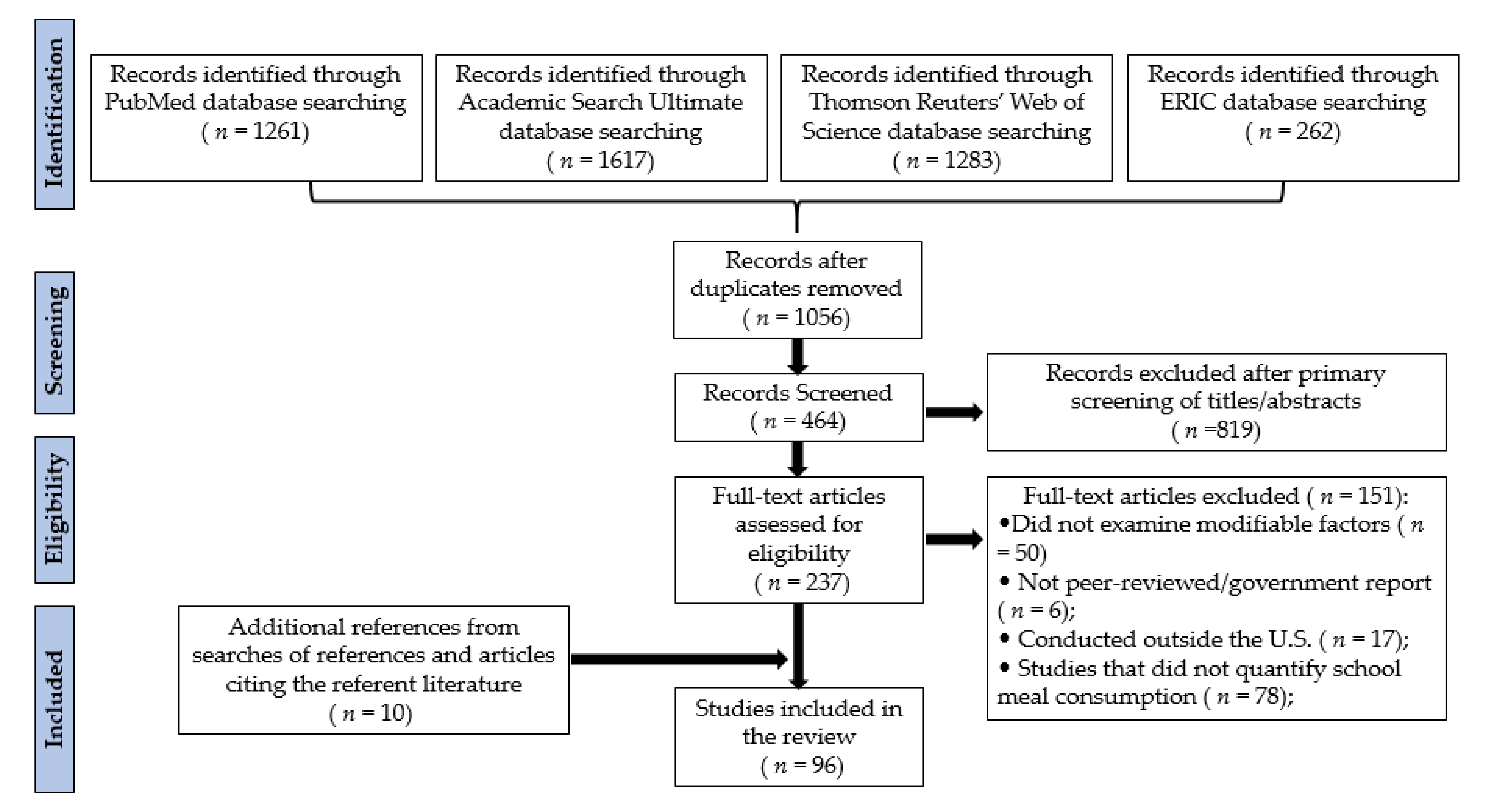

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Initiatives and Interventions Related to School Meals

3.1.1. Food Choices

3.1.2. Food Preparation: Palatability and Cultural Appropriateness

3.1.3. Food Preparation: Pre-Slicing Fruits

3.1.4. Taste Tests

3.2. Initiatives and Interventions Related to the Cafeteria Environment

3.2.1. Choice Architecture

Rewards

Smarter Lunchroom Strategies

Portion Sizes and Providing Meal Components at Different Times

3.2.2. Nutrition Education

3.2.3. School Lunch Duration

3.2.4. Recess before Lunch

3.3. Policies

3.3.1. Federal Policies: The Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act (HHFKA)

3.3.2. Local and State Policies: Access to Competitive Foods

3.3.3. Other Local Policies

| Author, Year | Location; Participant Characteristics | Study Design 1 | Year(s) | Exposure(s) | Outcome Measure(s) | Results | Risk of Bias 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choices | |||||||

| Adams et al. 2005 [55] | San Diego, CA; 2 school districts (2 elementary schools per district [288 students total]) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2003 | Choices: Salad bar and pre-portioned options with varying number of options were provided | Weighed plate waste | Selection: There were no significant associations. Consumption: The presence of a salad bar alone was not associated with F/V selection or consumption. However, a greater number of F/V options was associated with a trend in increased F/V consumption. | High |

| Ang et al. 2019 [51] | New York City, NY; 14 elementary schools [877 trays collected from students in grade 2–3) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2015–16 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Pre-plating vegetables (vs. optional for the student to select a vegetable) was associated with a small increase in consumption (0.02 cups; p < 0.001). Positioning vegetables first on the serving line was not associated with vegetable consumption. Among students who selected fruit, pre-sliced fruit was associated with greater consumption (0.23 cups more; p = 0.02) than whole fruit.. Recess before lunch was associated with a small increase in fruit consumption (0.08 cups; p < 0.001) and vegetable consumption (0.007 cups; p = 0.04).Multiple fruit options and attractive serving bowls were not associated with fruit consumption. Lunch duration was not associated with consumption (although less than 15% of measurements had lunch durations of ≥20 min). | Low |

| Bean et al. 2018 [53] | VA; 2 elementary schools (725 trays collected from students in grades 1–5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2015–16 | Choices: Salad bars were added to the serving line with additional fruit and vegetable options | Digital imagery | Selection: Salad bars were associated with an increase in the number of F/V selected (1.81 vs. 2.58 F/V; p < 0.001). Consumption: Salad bars were associated with a decrease in F/V consumption by 0.65 cups (p < 0.001). | High |

| Cullen et al. 2015A [44] | Houston, TX; 8 elementary schools and 4 middle schools (1576 trays from students in grades K-8) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | Fall 2011 | Choices: Students in intervention schools were allowed to select one fruit serving and two vegetables servings (three total). Students in comparison schools were limited to no more than two servings of fruits and/or vegetables | Visual estimation | Selection: In the intervention elementary schools, there was significantly greater selection of fruits and starchy vegetables and decreased selection of juice compared with control schools. In the intervention middle schools, there was significantly greater selection of fruit, total vegetables, and starchy vegetables compared with control schools.Consumption: In the intervention elementary schools, students consumed more vegetables compared than the comparison group (0.14 cups vs. 0.10 cups; p < 0.01). There was no impact on whole fruit consumption. In the intervention middle schools, students increased their consumption of both vegetables (0.17 cups vs. 0.10; p<0.01) and whole fruits (0.19 vs. 0.09; p < 0.001). | High |

| Greene et al. 2017 [49] | NY; 7 middle schools (8502 trays from students in grades 5–8) | RCT | 2014 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: The intervention was associated with a 36% increase in fruit selection (p < 0.001), but no significant changes in vegetable or milk selection. Consumption: The intervention was associated with a 23% increase in fruit consumption (p < 0.001). There was no association with vegetable or milk consumption. | Low |

| Hakim et al. 2013 [46] | Midwest Region; 1 K-8 school (2148 trays from students in grades K-8) | QE: Pre/Post (no comparison group) | 2011–2012 | Choices: Students were provided with a choice of three F/V options | Weighed plate waste and visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with a 15% increase in fruit consumption and a 16% increase in vegetable consumption. | High |

| Johnson et al. 2017 [54] | New Orleans, LA; 21 middle and high schools (718 students in grades 7–12) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | N.S. | Choices: Salad bars were added | 24-hour recall (interviewer assisted ASA-24 Kids) | Selection: Not measured Consumption: There were no significant differences in vegetable consumption. Among students who reported consuming any fruit, students in schools with salad bars reported lower levels of fruit consumption at lunch compared to students in schools without salad bars. | High |

| Just et al. 2012 [45] | N.S.; 22 elementary schools (48,533 trays) | Cross-sectional | N.S. | Choices: The number of fruit and vegetables options available to students was assessed | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Each additional fruit or vegetable option offered increased the fraction of students who ate at least one serving of fruits and vegetables by 12%. | High |

| Liquori et al. 1998 [50] | New York City, NY; 2 elementary schools (590 students in grades K-6) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1995–96 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention arm with cooking lessons was associated with increased consumption of vegetables and whole grains among younger students (p < 0.01). No association was observed among older children exposed to the cooking intervention. The nutrition education (food environment) intervention was not associated with consumption. | High |

| Perry et al. 2004 [48] | St. Paul, MN; 26 elementary schools (1,668 students in grades 1 and 3) | RCT | 2000–2002 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with significant increases in total servings of F/V (excluding potatoes and juice). | Low |

| Taylor et al. 2018 [52] | CA; 2 elementary schools (112 students in grade 4) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2012–13 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in vegetable consumption. There was no association with fruit consumption. | High |

| Young et al. 2013 [47] | N.S.; 1 middle school (3810 trays from students in grades 6-8) | Cross-Sectional | 2011–12 | Policy: A new wellness policy required schools to implement the practices below:

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: After exposure to the wellness policy for over a semester, students consumed significantly more fruits and cooked vegetables. | High |

| Food Preparation: Palatability and Cultural Appropriateness | |||||||

| Bates et al. 2015 [64] | UT; 2 schools (1 middle and 1 high school [2760 school breakfasts from students in grades 7–12] | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | Not Stated | Palatability: Smoothies made with whole fruit, yogurt, and milk or fruit juice were offered to students | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Offering breakfast smoothies was associated with a 0.45 serving (p < 0.01) increase in fruit consumption. | High |

| Cohen et al. 2012 [56] | Boston, MA; 4 middle schools (3049 students in grades 3–8) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2009 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: The intervention was associated with a 51% increase in whole grain selection (p = 0.02). Consumption: Students in the intervention schools consumed 0.36 more servings of vegetables per day (p = 0.01) compared with students in control schools. There was no impact on milk, fruit, or whole grain consumption. | Low |

| Cohen et al. 2015 [57] | MA; 14 elementary and middle schools (2638 students in grades 3–8) | RCT | 2011–12 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Both the choice architecture and chef (i.e., palatability) intervention were associated with increased fruit and vegetable selection. There was no impact on white milk selection. Consumption: Only the chef intervention was associated with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. There was no impact on white milk consumption. | Low |

| Cohen et al. 2019 [58] | MA; 8 elementary and middle schools (1309 students in grades 3–8) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2012-13 | Palatability: A professional chef trained cafeteria staff to prepare healthier school lunches | Weighed plate waste | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in consumption of vegetables (62.2% vs. 38.2%; p = 0.005) and fruits (75.2 vs. 59.2%; 0 = 0.04) compared with control schools. There were no significant differences in entrée consumption. | Low |

| D’Adamo et al. 2021 [61] | Baltimore, MD; 1 high school (4570 trays from students in grades 9–12) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Palatability: Spices and herbs were added to vegetable recipes (based in prior pilot taste tests with some students) | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with an 18.2% increase in vegetable consumption (p < 0.001). | High |

| Fritts et al. 2019 [62] | PA; 1 middle/high school (~600–700 students ages 11–18) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2017 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was inversely associated with consumption for some of the vegetables offered. There was no association between repeated exposures to vegetables with added spices/herbs and vegetable consumption. | High |

| Hamdi et al. 2020 [63] | IL; 3 elementary schools (1255 trays from students in grades K-8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2018–19 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Selection was measured in only one of the participating schools. The odds of selecting a vegetable (i.e., broccoli) increased when students were exposed to taste tests. The odds of selecting fruit increased when all intervention components were implemented simultaneously. Consumption: The intervention components yielded inconsistent, but generally positive consumption results across the schools, particularly for fruits. | Low |

| Just et al. 2014 [60] | NY; 1 High School (3330 trays) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2012 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Student selection of chef-enhanced entrées increased by 5.7% percentage points (91.3% to 97%; p = 0.01). Student selection of salad, which was served with the pizza, increased by 21% percentage points (p < 0.001). Consumption: The chef enhanced pizza was not associated with differences in main dish consumption. However, as more students selected salad with the pizza, vegetable consumption increased by 16.5% (p = 0.005). | High |

| Zellner et al. 2017 [59] | Philadelphia, PA; 2 elementary schools (students in grades 3–4) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | N.S. |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in sweet potato fry consumption at the beginning of the school year and an increase in cauliflower consumption at the end of the school year. | Very High |

| Food Preparation: Pre-Slicing Fruit | |||||||

| Ang et al. 2019 [51] | New York City, NY; 14 elementary schools [877 trays collected from students in grade 2–3) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2015–16 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measuredConsumption: Pre-plating vegetables (vs. optional for the student to select a vegetable) was associated with a small increase in consumption (0.02 cups; p < 0.001). Positioning vegetables first on the serving line was not associated with vegetable consumption Among students who selected fruit, pre-sliced fruit was associated with greater consumption (0.23 cups more p = 0.02) than whole fruit. Recess before lunch was associated with a small increase in fruit consumption (0.08 cups; p < 0.001) and vegetable consumption (0.007 cups; p = 0.04). Multiple fruit options and attractive serving bowls were not associated with fruit consumption. Lunch duration was not associated with consumption (although less than 15% of measurements had lunch durations of ≥20 min). | Low |

| Greene et al. 2017 [49] | NY; 7 middle schools (8502 trays from students in grades 5-8) | RCT | 2014 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: The intervention was associated with a 36% increase in fruit selection (p < 0.001), but no significant changes in vegetable or milk selection. Consumption: The intervention was associated with a 23% increase in fruit consumption (p < 0.001). There was no association with vegetable or milk consumption. | Low |

| McCool et al. 2005 [66] | N.S.; 1 elementary and 1 middle school | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Pre-sliced Fruit: Sliced apples and/or whole apples | Aggregate plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Elementary school students consumed more fruit when apples were pre-sliced than when they were served whole. Middle school students consumed more fruit when they had a choice between pre-sliced or whole apples. | Very High |

| Quinn et al. 2018 [70] | King County, WA; 11 middle and high schools (2309 trays) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2013–14 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: A greater proportion of students selected fruit in the intervention schools compared with control schools. There was no significant change in vegetable selection. Consumption: Pre-sliced fruit and choice architecture were not associated with significant differences in the quantities of fruits, vegetables, or milk consumed. | High |

| Smathers et al. 2020 [65] | N.S.; 2 elementary schools (students in grades PreK-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Pre-sliced Fruit: Sliced apples were compared with whole apples | Aggregate weighed plate waste | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: Students consumed 2.48 times more fruit by weight when eating pre-sliced versus whole apples (p < 0.001). | Very High |

| Swanson et al. 2009 [68] | KY; 1 elementary school (979 students in grades K-4) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2007 | Pre-sliced Fruit: Sliced apples and oranges were compared with whole apples and oranges | Digital imagery | Selection: Pre-slicing oranges was associated with increased selection. No significant differences were observed with pre-sliced apples. Consumption: A greater proportion of students consumed at least half of a fruit serving when pre-sliced (vs. whole) oranges were served. There were differences observed by grade level (i.e., higher consumption rates among younger students with pre-sliced oranges). The intervention was not associated with consumption for apples. | High |

| Thompson et al. 2017 [69] | Hennepin County, MN; 2 elementary schools (373 students in grades K-4) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2013 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in the percentage of students selecting a fruit serving (95.1% vs. 98.1%; p = 0.02). There was no significant change in vegetable selection. Consumption: The intervention was not associated with fruit or vegetable consumption. | Low |

| Wansink et al. 2013 [67] | Wayne County, NY; 6 middle schools (334 trays) | RCT | 2011 | Pre-sliced Fruit: Sliced apples were compared with whole apples | Visual estimation | Selection: There was a significant increase in apple selection in intervention schools when pre-sliced apples were offered (5% difference in sales between intervention and comparison schools; p < 0.001). Consumption: Pre-slicing apples was associated with an increase in the percent of students who selected an apple and ate more than half (75% increase; p = 0.02). | Low |

| Taste Tests | |||||||

| Alaimo et al. 2015 [73] | Grand Rapids, MI; 6 elementary schools (4 intervention and 2 control 815 students in grades 3–5) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2009–10 to 2010–11 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The multi-component intervention was associated with significant increases in fruit consumption. No differences in consumption of vegetables, milk, grains, or protein were observed. | Low |

| Blakeway et al. 1978 [75] | Little Rock, AR; 16 elementary schools (5000 students in grades 1-3) | RCT | N.S. |

| Aggregate plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Students in intervention schools consumed greater amounts of whole wheat rolls (grades 2 and 3 only) and cottage cheese (grades 1 and 2 only) compared to the comparison group. Sweet potato custard consumption increased in both the intervention and control group. No other significant differences were observed. | High |

| Bontranger Yoder et al. 2014 [77] | WI; 9 elementary schools (1117 students in grades 3–5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2010–11 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in F/V consumption, although the farm to school components were inconsistently implemented across the participating schools. | Low |

| Bontranger Yoder et al. 2015 [78] | WI; 11 elementary schools (7117 trays from students in grades 3–5) | Cross-sectional and Pre/post (no comparison group)* *For Policy only | 2010 to 2013 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention components (i.e., nutrition education, taste tests, and other activities) were not associated with differences in F/V consumption. There was no change in consumption before or after implementation of the HHFKA. | High |

| Georgiou (1998 Gov’t Report) [74] | OR; 1 elementary school (40 students in grade 3) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1997 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in consumption of calories from fruits (28 kcal; p < 0.01). No significant differences in vegetable and grain consumption were observed. | High |

| Hamdi et al. 2020 [63] | IL; 3 elementary schools (1255 trays from students in grades K-8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2018–19 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Selection was measured in only one of the participating schools. The odds of selecting a vegetable (i.e., broccoli) increased when students were exposed to taste tests. The odds of selecting fruit increased when all intervention components were implemented simultaneously. Consumption: The intervention components yielded inconsistent, but generally positive consumption results across the schools, particularly for fruits. | Low |

| Just et al. 2014 [60] | NY; 1 High School (3330 trays) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2012 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Student selection of chef-enhanced entrées increased by 5.7% percentage points (91.3% to 97%; p = 0.01). Student selection of salad, which was served with the pizza, increased by 21% percentage points (p < 0.001). Consumption: The chef enhanced pizza was not associated with differences in main dish consumption. However, as more students selected salad with the pizza, vegetable consumption increased by 16.5% (p = 0.005). | High |

| Mazzeo et al. 2017 [71] | Mid-Atlantic region; 2 elementary schools (2087 trays from students in grades 1–3) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2014–15 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with reduced F/V waste. | High |

| Morrill et al. 2016 [72] | UT; 6 elementary schools (2292 students in grades | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2011 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with increased F/V consumption. At 6 months follow-up (after the intervention ended), only the intervention arm with prizes (plus nutrition education and taste tests) was associated with sustained increased consumption. | Low |

| Perry et al. 2004 [48] | St. Paul, MN; 26 elementary schools (1668 students in grades 1 and 3) | RCT | 2000–2002 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with significant increases in total servings of F/V (excluding potatoes and juice). | Low |

| Reynolds et al. 2000 [76] | AL; 28 elementary schools (425 students in grade 4) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1994 to 1996 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with significant differences in fruits or vegetables consumed. | Low |

| Author, Year | Location; Participant Characteristics | Study Design 1 | Year(s) | Exposure(s) | Outcome Measure(s) | Results | Risk of Bias 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice Architecture: Rewards | |||||||

| Blom-Hoffman et al. 2004 [85] | Northeast Region; 1 elementary school (students in grades K-1) | RCT | N.S. |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in vegetable consumption. | High |

| Hendy et al. 2005 [79] | PA; 1 elementary school (188 students in grades 1, 2, and 4) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Choice architecture: Students received a reward for eating F/V (small prize for eating ≥1/8 cup) | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The reward intervention was associated with an increase in consumption for both fruits and vegetables. | High |

| Hoffman et al. 2010 [83] | New England region; 4 elementary schools (297 students in grades 1 and 2) | RCT | 2006 to 2007 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in fruit consumption in both year 1 (29 g difference; p < 0.0001) and year 2 (21 g difference; p < 0.005), and an increase in vegetable consumption in year 1 (6 g difference; p < 0.01). No significant difference in vegetable consumption was observed in year 2. | Low |

| Hoffman et al. 2011 [84] | New England region; 4 elementary schools (297 students in grades 1 and 2) | RCT | 2005 to 2009 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in F/V at lunch during the study period, but at one year follow-up (after the intervention concluded), there was no longer a difference in F/V consumption. | Low |

| Hudgens et al. 2017 [86] | Cincinnati, OH; 1 elementary school (207 trays from students in grades K-6) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2014–15 | Choice Architecture: Students received emoticons and rewards (small prizes) for selecting a lunch with a fruit, vegetable, unflavored milk, and whole grain | Visual estimation | Selection: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in the selection of plain fat-free milk and vegetables, and a decrease in the selection of flavored milk. Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in consumption for any meal component. | High |

| Jones et al. 2014 [80] | Logan, UT: 1 elementary school (K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2013 | Choice Architecture: Students received rewards (i.e., virtual currency or teacher continuing to read a story) for eating FV. Students also received teacher encouragement to eat more FV when average consumption levels were lower | Aggregate plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: On days when fruits were targeted, fruit consumption was 39% higher (p < 0.01), but there was no change in vegetable consumption. On days when vegetables were targeted, vegetable consumption was 33% higher (p < 0.05), but there was no change in fruit consumption. | Very High |

| Machado et al. 2020 [82] | OR; 1 elementary school (797 trays from students in grades K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2016–17 | Choice Architecture: Elements included adult role modeling, verbal prompts, and rewards (i.e., classroom party and t-shirts) for F/V consumption in the cafeteria | Digital imagery | Selection: There was a 16% increase in the proportion of students selecting a vegetable (p < 0.01). Consumption: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in the proportion of students consuming all their fruits (11% increase; p < 0.01) and all their vegetables (8.7% increase; p < 0.01). There was also a decrease in the percent of students not consuming any of the fruits on their trays (16.0% decrease; p < 0.001). | High |

| Mazzeo et al. 2017 [71] | Mid-Atlantic region; 2 elementary schools (2087 trays from students in grades 1–3) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2014–15 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with reduced F/V waste. | High |

| Morrill et al. 2016 [72] | UT; 6 elementary schools (2292 students in grades | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2011 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with increased F/V consumption. At 6 months follow-up (after the intervention ended), only the intervention arm with prizes (plus nutrition education and taste tests) was associated with sustained increased consumption. | Low |

| Perry et al. 2004 [48] | St. Paul, MN; 26 elementary schools (1668 students in grades 1 and 3) | RCT | 2000–2002 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with significant increases in total servings of F/V (excluding potatoes and juice). | Low |

| Wengreen et al. 2013 [81] | UT; 1 elementary school (253 students in grades 1–5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2010-11 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with significant increases in fruit and vegetable consumption. | High |

| Choice Architecture: Visual Appeal, verbal prompts, and re-ordering the lunch line | |||||||

| Adams et al. 2016 [88] | Phoenix, AZ; 2 school districts (3 middle schools per district [students total]) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2013 | Choice Architecture: The placement of the salad bar was either on the serving line or after the serving line | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Students selected 5.4 times more fresh fruits and vegetables by weight (95% CI, 4.0–7.2) when the salad bar was on the serving line (vs. after the serving line). Consumption: Students consumed 4.83 times more F/V (95% CI 3.40 to 6.81) when the salad bar was on the serving line (vs. after the serving line). | Low |

| Ang et al. 2019 [51] | New York City, NY; 14 elementary schools [877 trays collected from students in grade 2–3) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2015–16 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Pre-plating vegetables (vs. optional for the student to select a vegetable) was associated with a small increase in consumption (0.02 cups; p < 0.001). Positioning vegetables first on the serving line was not associated with vegetable consumption. Among students who selected fruit, pre-sliced fruit was associated with greater consumption (0.23 cups more p = 0.02) than whole fruit. Recess before lunch was associated with a small increase in fruit consumption (0.08 cups; p < 0.001) and vegetable consumption (0.007 cups; p = 0.04). Multiple fruit options and attractive serving bowls were not associated with fruit consumption. Lunch duration was not associated with consumption (although less than 15% of measurements had lunch durations of ≥20 min). | Low |

| Blondin et al. 2018 [93] | N.S.; 6 elementary schools (students in grades 3–4) | Cross-sectional | 2015 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: When juice was offered with breakfast, the percent of students selecting milk decreased. Consumption: Offering juice at breakfast was associated with a 12% increase in milk waste (p < 0.001). Teacher encouragement to select milk was associated with a 9% increase in milk waste (p = 0.009). Student engagement in other activities during breakfast was associated with a 10% decrease in milk waste (p < 0.001). | Low |

| Cohen et al. 2015 [57] | MA; 14 elementary and middle schools (2638 students in grades 3–8) | RCT | 2011–12 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Both the choice architecture and chef (i.e., palatability) intervention were associated with increased fruit and vegetable selection. There was no impact on white milk selection. Consumption: Only the chef intervention was associated with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. There was no impact on white milk consumption. | Low |

| Goto et al. 2013 [90] | CA; 3 elementary schools (677 students in grades 1–6) | RCT | 2011 | Choice Architecture: The quantity of white milk was increased compared with the quantity of chocolate milk. Some schools requested to decrease the visibility of chocolate milk from the lunch line. | Weighed plate waste | Selection: When the visibility of chocolate milk was decreased, there was an 18% percentage-point increase in white milk selection. Changing the quantity of white milk available was not associated with changes in selection. Consumption: The interventions were not associated with differences in white milk consumption. | High |

| Greene et al. 2017 [49] | NY; 7 middle schools (8502 trays from students in grades 5–8) | RCT | 2014 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: The intervention was associated with a 36% increase in fruit selection (p < 0.001), but no significant changes in vegetable or milk selection. Consumption: The intervention was associated with a 23% increase in fruit consumption (p < 0.001). There was no association with vegetable or milk consumption. | Low |

| Gustafson et al. 2017 [87] | Kearney, N; 4 elementary schools (1614 trays from students in grades K-5) | RCT | 2014–15 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: The intervention arm with both student participation in the poster design and the presence of marketing was associated with an increase in the selection of vegetables. Consumption: The intervention arm with both student participation in the poster design and the presence of marketing was associated with a significant increase in vegetable consumption compared with the control group. | High |

| Hamdi et al. 2020 [63] | IL; 3 elementary schools (1255 trays from students in grades K-8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2018–19 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Selection was measured in only one of the participating schools. The odds of selecting a vegetable (i.e., broccoli) increased when students were exposed to taste tests. The odds of selecting fruit increased when all intervention components were implemented simultaneously. Consumption: The intervention components yielded inconsistent, but generally positive consumption results across the schools, particularly for fruits. | Low |

| Hanks et al. 2012 [91] | Corning, NY; 1 high school (1084 trays from students) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2011 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: The intervention was associated with an 18% increase in healthier food selection (p < 0.001). Consumption: There was no significant change in the consumption of healthy foods, but there was a significant decrease in consumption of less healthy foods (27.9% decrease; p < 0.001). | High |

| Hanks et al. 2013 [89] | NY; Two Middle/High schools (3762 trays from students in grades 7–12). | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2011 | Choice Architecture: The following components were included: a convenience line with healthier options; placing healthier foods first in line; adding attractive bowls and descriptive names; and providing verbal prompts to select healthy options | Visual estimation | Selection: Students were 13.4% more likely to take a fruit (p = 0.01) and 23% more likely to take a vegetable (p < 0.001) post-implementation. Consumption: Choice architecture was associated with an 18% increase in fruit consumption (p = 0.004) and 25% increase in vegetable consumption (p < 0.001). | High |

| Koch et al. 2020 [92] | New York City, NY; 7 high schools | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2017 to 2018 | Choice Architecture: The intervention included a more open lunch line, comfortable seating options, wall art, and promotional signage | Digital imagery | Selection: Fruit and vegetable selection decreased (statistical significance not assessed). Consumption: After a year of exposure to the intervention, there were no changes in vegetable consumption and significant decreases in consumption of fruits and grains. | High |

| Quinn et al. 2018 [70] | King County, WA; 11 middle and high schools (2309 trays) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2013–14 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: A greater proportion of students selected fruit in the intervention schools compared with control schools. There was no significant change in vegetable selection. Consumption: Pre-sliced fruit and choice architecture were not associated with significant differences in the quantities of fruits, vegetables, or milk consumed. | High |

| Reicks et al. 2012 [96] | Richfield, MN; 1 elementary school (students in grades K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2011 | Choice Architecture: Photographs of vegetables were placed on lunch trays | Aggregate plate waste | Selection: The intervention was associated with an 8.5% percentage point increase in green beans (p < 0.001) and a 25.2% percentage point increase in carrot selection (p < 0.001). Consumption: Among students who selected vegetables, the intervention was associated with a decrease in carrot consumption (27g vs. 31g; p < 0.001) and no impact on green bean consumption. | Very High |

| Schwartz 2007 [94] | CT; 2 elementary schools (students in grades 1–4) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2005 | Choice Architecture: Staff provided verbal prompts on the lunch lune encouraging fruit selection | Visual estimation | Selection: The intervention was associated with significantly greater odds of selecting fruit. Consumption: Among students who selected a fruit, there were no differences in fruit consumption. | High |

| Thompson et al. 2017 [69] | Hennepin County, MN; 2 elementary schools (373 students in grades K-4) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2013 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in the percentage of students selecting a fruit serving (95.1% vs. 98.1%; p = 0.02). There was no significant change in vegetable selection. Consumption: The intervention was not associated with fruit or vegetable consumption. | Low |

| Wansink et al. 2015 [95] | Lansing, NY; 1 high school (554 trays from students in grades 9–12) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2012 | Choice Architecture: Salad greens grown by one classroom were added to the school salads, and posters and announcements were introduced to promote this addition | Visual estimation | Selection: The intervention was associated with an increase in salad selection from 2% to 10% (p < 0.001). Consumption: The intervention was associated with a decrease in salad consumption (94% to 67% of a serving consumed; p = 0.007). | High |

| Choice Architecture: Portion Sizes or Modifying When Students Have Access to Meal Components | |||||||

| Elsbernd et al. 2016 [100] | Richfield, MN; 1 elementary school (~500 students in grades K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Choice Architecture: Students were offered vegetables (red pepper) in the hallway outside the cafeteria while waiting on the lunch line. Staff provided verbal prompts to eat the peppers while waiting on the lunch line. | Visual estimation | Selection: The selection of red pepper increased from 8% to 65% (statistical significance not assessed). Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in overall vegetable consumption. | High |

| Miller et al. 2015 [99] | Richfield, MN; 1 elementary school (~680 students in grades K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2011 | Choice Architecture: There was a 50% increase in portion sizes for F/V | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Larger portion sizes was associated with a significant increase in the proportion of students selecting oranges and a decrease in the proportion of students selecting applesauce. Consumption: Increasing the portion sizes for F/V was associated with increased consumption (range 13–42g increase) among those who selected the meal component. | Low |

| Ramsay et al. 2013 [97] | N.S.; 1 Kinder Center (elementary school with only kindergarten) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2010 | Choice Architecture: An increase in the portion size of the entrée (i.e., the number of chicken nuggets offered) | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Students selected more chicken nuggets when they were able to choose larger serving sizes. Consumption: Larger portion sizes of chicken nuggets were associated with greater consumption. | High |

| Redden et al. 2015 [101] | Richfield, MN; 1 elementary school (1435 trays [study 1] and 2632 trays [study 2] from students in grades K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Choice Architecture: In Study 1, vegetables (mini carrots) were available on a table while students waited in line for food. In Study 2, vegetables (broccoli) were handed to students while they waited in line for food. | Aggregate plate waste | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: In Study 1, offering mini carrots to students while they waited in the lunch line was associated with an overall increase in carrot consumption at lunch compared with a control day (12.7g vs. 2.4g; p < 0.001). In Study 2, with a longer exposure to the intervention, offering broccoli was associated with increased consumption that persisted over time. | Very High |

| Zellner et al. 2016 [102] | Philadelphia, PA; 1 elementary school (47 trays from students in grades 3–4) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | N.S. | Choice Architecture: Fruit was served later in the meal versus at the same time as the rest of the school lunch | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Delaying when fruit was served was associated with greater kale consumption (p = 0.0017) compared with when fruit was served at the same time as the rest of the meal. | Very High |

| Author, Year | Location; Participant Characteristics | Study Design 1 | Year(s) | Exposure(s) | Outcome Measure(s) | Results | Risk of Bias2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Education | |||||||

| Auld et al. 1998 [105] | Denver, CO; 10 elementary schools (3 intervention and 3 comparison) [~850 students in grades k-5] | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1995–96 to 1996–97 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in F/V consumption by 0.4 serving (p < 0.001). | Low |

| Auld et al. 1999 [104] | Denver, CO; 4 elementary schools (2 intervention and 2 control [~760 students total in grades 2–4]) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1997–98 | Nutrition Education: 16 nutrition lessons were taught alternatively by teachers and special resource teachers | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Nutrition education was associated with an increase in F/V consumption by 0.36 servings (p < 0.001). | Low |

| Burgess-Champoux et al. 2008 [106] | Minneapolis metropolitan area, MN: 2 elementary schools (150 students in grades 4 and 5) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2005 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: In the intervention school, whole grain consumption increased by 1 serving (p < 0.0001) and refined grain consumption decreased by 1 serving (p < 0.001) compared with the control school. | High |

| Epstein-Solfield et al. 2018 [111] | WA; 1 elementary school (149 students in grades 3 and 5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2017 | Nutrition Education: Lessons were provided for 8 weeks (20 min per session) focused on the benefits of consuming F/V | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in F/V consumption. | High |

| Head 1974 [107] | NC; 4 elementary, 4 middle, and 2 high schools (students in grade 5, 7, and 10) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | N.S. | Nutrition Education: Lessons were provided on basic nutrition, dietary patterns, and food composition | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: There was a significant decrease in plate waste with nutrition education. | Low |

| Ishdorj et al. 2013 [110] | Nationally representative sample (SNDA-III); 256 schools (2096 students) | Cross-sectional | 2004–05 |

| 24 h recall | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Policies that place restrictions on the sales of competitive foods were associated with greater fruit consumption. Policies that restrict desserts were associated with greater vegetable consumption. Policies that limited French fries were associated with lower fruit consumption. Limiting whole and 2% milk was associated with greater fruit and vegetable consumption. Nutrition education and policies that increase the amount of fresh fruit and vegetable available daily at lunch policies were not associated with consumption of fruits or vegetables. | High |

| Jones et al. 2015 [109] | SC; 15 elementary and 3 middle schools (students in grades K-8) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2011 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Students in the intervention schools consumed on average less fruit than students in control schools. There was no significant association with vegetable consumption. | High |

| Larson et al. 2018 [112] | Southwest region; 2 elementary schools (159 students in grades 4–5) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group | N.S. | Nutrition Education: Fruit and vegetable consumption was promoted via cartoon characters, posters, and goal setting | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in F/V consumption. | High |

| Prescott et al. 2019 [108] | CO; 2 middle schools (1596 trays from students in grade 6–8) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2017–18 | Nutrition education: The 6th grade curriculum focused on sustainable food systems. 6th grade students created posters to educate the 7–8th grade students | Digital imagery | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: During the intervention, students in intervention school increased their vegetable consumption (due to significantly lower consumption rates at baseline, the intervention eliminated the difference versus control). At 5 months follow-up, the intervention students wasted significantly less salad bar vegetables compared with the control students (24g vs. 50g; p = 0.029). | High |

| Serebrennikov et al. 2020 [113] | Midwestern Region; 3 elementary schools (98 students in grade 2) | RCT | 2016 | Nutrition Education: A curriculum related to knowledge and preferences for F/V was implemented bi-weekly for 6 weeks | Digital imagery | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: Nutrition education was not associated with significant differences in fruits or vegetables consumed. | Low |

| Sharma et al. 2019 [103] | Houston/Dallas, TX; 3 elementary schools (115 students in grades 4–5) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2017-18 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: There was no change in selection among intervention schools but there was a decrease in the comparison schools, which resulted in a significant difference in selection. Consumption: The intervention was associated with significant decreases in F/V waste at lunch (p < 0.001). | Low |

| Multi-Component Nutrition Education with Choice and/or Taste Test Components | |||||||

| Alaimo et al. 2015 [73] | Grand Rapids, MI; 6 elementary schools (4 intervention and 2 control [815 students in grades 3-5]) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2009–10 to 2010–11 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The multi-component intervention was associated with significant increases in fruit consumption. No differences in consumption of vegetables, milk, grains, or protein were observed. | Low |

| Blakeway et al. 1978 [75] | Little Rock, AR; 16 elementary schools (5000 students in grades 1–3) | RCT | N.S. |

| Aggregate plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Students in intervention schools consumed greater amounts of whole wheat rolls (grades 2 and 3 only) and cottage cheese (grades 1 and 2 only) compared to the comparison group. Sweet potato custard consumption increased in both the intervention and control group. No other significant differences were observed. | High |

| Blom-Hoffman et al. 2004 [85] | Northeast Region; 1 elementary school (students in grades K-1) | RCT | N.S. |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in vegetable consumption. | High |

| Bontranger Yoder et al. 2014 [77] | WI; 9 elementary schools (1117 students in grades 3–5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2010-11 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with differences in F/V consumption, although the farm to school components were inconsistently implemented across the participating schools. | Low |

| Bontranger Yoder et al. 2015 [78] | WI; 11 elementary schools (7117 trays from students in grades 3–5) | Cross-sectional and Pre/post (no comparison group) * * For Policy only | 2010 to 2013 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention components (i.e., nutrition education, taste tests, and other activities) were not associated with differences in F/V consumption. There was no change in consumption before or after implementation of the HHFKA. | High |

| Georgiou (1998 [Gov’t Report]) [74] | OR; 1 elementary school (40 students in grade 3) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1997 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: The intervention was associated with an increase in consumption of calories from fruits (28 kcal; p < 0.01). No significant differences in vegetable and grain consumption were observed. | High |

| Liquori et al. 1998 [50] | New York City, NY; 2 elementary schools (590 students in grades K-6). | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1995-96 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention arm with cooking lessons was associated with increased consumption of vegetables and whole grains among younger students (p < 0.01). No association was observed among older children exposed to the cooking intervention. The nutrition education (food environment) intervention was not associated with consumption. | High |

| Reynolds et al. 2000 [76] | AL; 28 elementary schools (425 students in grade 4) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1994 to 1996 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention was not associated with significant differences in fruits or vegetables consumed. | Low |

| Taylor et al. 2018 [52] | CA; 2 elementary schools (112 students in grade 4) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2012–13 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: No significant associations Consumption: The intervention was associated with a significant increase in vegetable consumption. There was no association with fruit consumption. | High |

| Young et al. 2013 [47] | N.S.; 1 middle school (3810 trays from students in grades 6–8) | Cross-Sectional | 2011–12 | Policy: A new wellness policy required schools to implement the practices below:

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: After exposure to the wellness policy for over a semester, students consumed significantly more fruits and cooked vegetables. | High |

| Author, Year | Location; Participant Characteristics | Study Design 1 | Year(s) | Exposure(s) | Outcome Measure(s) | Results | Risk of Bias 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Lunch Duration | |||||||

| Ang et al. 2019 [51] | New York City, NY; 14 elementary schools (877 trays collected from students in grade 2–3) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2015–16 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Pre-plating vegetables (vs. optional for the student to select a vegetable) was associated with a small increase in consumption (0.02 cups; p < 0.001). Positioning vegetables first on the serving line was not associated with vegetable consumption Among students who selected fruit, pre-sliced fruit was associated with greater consumption (0.23 cups more p = 0.02) than whole fruit. Recess before lunch was associated with a small increase in fruit consumption (0.08 cups; p < 0.001) and vegetable consumption (0.007 cups; p = 0.04). Multiple fruit options and attractive serving bowls were not associated with fruit consumption. Lunch duration was not associated with consumption (although less than 15% of measurements had lunch durations of ≥20 min). | Low |

| Bergman et al. 2004 A [114] | WA; 2 elementary schools (1877 trays from students in grades 3–5) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | N.S. | Lunch Duration: The times varied from 20–30 min | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Longer lunch periods were associated with significantly greater school meal consumption (72.8% vs. 56.5% consumed; p < 0.0001). | High |

| Cohen et al. 2016 [19] | MA; 6 elementary and middle schools (1001 students in grades 3–8) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2011–12 | Lunch Duration: The times varied from 20–30 min (the amount of seated time in the cafeteria was calculated) | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Fruit selection was lower when students had less time to eat (46.9% vs. 57.3%; p < 0.0001). Consumption: A shorter lunch period (less than 20 min of seated time) was associated with a decreased consumption of entrées (12.8% reduction; p < 0.0001), milk (10.3% reduction; p<0.0001), and vegetables (11.8% reduction, p<0.0001). | Low |

| Gross et al. 2018 [115] | New York City, NY; 10 elementary schools (382 students ages 6–8 years) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2013 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: On average, 74% of students selected a fruit, 69% selected a vegetable, and 73% selected a whole grain (statistical significance not assessed). Consumption: A longer lunch duration (≥30 min) was associated with higher consumption of fruits (odds ratio [OR] = 2.0; p = 0.02) and whole grains (OR = 2.1; p <0.05). Quieter cafeterias were associated with eating more vegetables (OR = 3.9; p < 0.001) and whole grains (OR= 2.7; p < 0.001). Less crowding was associated with eating more fruit (OR = 2.3; p = 0.04) and whole grains (OR = 3.3; p < 0.001). | Low |

| Recess Before Lunch | |||||||

| Ang et al. 2019 [51] | New York City, NY; 14 elementary schools [877 trays collected from students in grade 2–3) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2015–16 |

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Pre-plating vegetables (vs. optional for the student to select a vegetable) was associated with a small increase in consumption (0.02 cups; p < 0.001). Positioning vegetables first on the serving line was not associated with vegetable consumption Among students who selected fruit, pre-sliced fruit was associated with greater consumption (0.23 cups more p = 0.02) than whole fruit.. Recess before lunch was associated with a small increase in fruit consumption (0.08 cups; p < 0.001) and vegetable consumption (0.007 cups; p = 0.04). Multiple fruit options and attractive serving bowls were not associated with fruit consumption. Lunch duration was not associated with consumption (although less than 15% of measurements had lunch durations of ≥20 min). | Low |

| Bergman et al. 2004 B [116] | W; 2 elementary schools (2008 trays from students grades 3–5) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | N.S. | Recess before lunch | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was associated with significantly greater school meal consumption (72.8% vs. 59.9% consumed; p < 0.0001). | High |

| Chapman et al. 2017 [117] | New Orleans, LA; 8 elementary schools (20,183 trays from students in grades 4 and 5) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2014 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was associated with a 5.1% increase in fruit consumption (p = 0.009). There was no association between the timing of recess and consumption of the entrée, vegetable, or milk. Students who had a very early lunch consumed 5.8% less of their entrées (p < 0.001) and 4.5% less of their milk (p = 0.047) compared with students who had lunch at a traditional lunch hour. Additionally, students who had a very late lunch consumed 13.8% less of their entrées (p < 0.001) and 15.9% less of their fruit (p < 0.001). | Low |

| Fenton et al. 2015 [123] | CA; 31 elementary schools (2167 students in grades 4–5). | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2011–12 | Recess before lunch | 24 hour recalls (diary assisted) | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was not associated with differences in FV consumption at lunch. | Low |

| Getlinger et al. 1996 [118] | Rockfort, IL; 1 elementary school (67 students in grades 1–3) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 1995 | Recess before lunch | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was associated with significant reductions in food waste for meat/meat alternatives, vegetables, and milk. There were no significant differences observed for fruits or grains. | High |

| Hunsberger et al. 2014 [21] | Madras, OR; 1 elementary school (261 students in grades K-2) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2009–10 | Recess before lunch | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Students with recess before lunch were roughly 20% more likely to drink an entire carton of milk (42% vs. 25%; p < 0.001) and consumed on average 1.3 oz more milk compared with students who had recess after lunch. There were no significant differences in consumption of entrées, vegetables, or fruits. | High |

| McLoughlin et al. 2019 [120] | IL; 2 elementary schools (103 students in grades 4–5) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2016 | Recess before lunch | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Overall, 57% of students selected fruits, 26% selected vegetables, 68% selected entrées and 64% selected milk (statistical significance not assessed). Consumption: Recess before lunch was associated with on average greater milk consumption. There was no association between recess before lunch and the amount of entrée, fruit, or vegetable consumed. | High |

| Price et al. 2015 [122] | Orem, UT; 7 elementary schools (22,939 trays from students in grades 1–6) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 2010–11 to 2011–12 | Recess before lunch | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was associated with a 0.16 serving increase in fruit and vegetable consumption (p < 0.01). | Low |

| Strohbehn et al. 2016 [119] | Midwestern Region; 3 elementary school (students in grade 3) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2012 | Recess before lunch | Digital imagery and weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was associated with inconsistent findings; while the average waste was reduced for grains, meat/meat alternatives, and fruits, the average waste increased for vegetables. | High |

| Tanaka et al. 2005 [121] | Oahu, HI; 1 elementary school (students in 6th grade) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2004 | Recess before lunch | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Recess before lunch was not associated with consumption of F/V, milk, or other school meal components. | High |

| Author, Year | Location; Participant Characteristics | Study Design 1 | Year(s) | Exposure(s) | Outcome Measure(s) | Results | Risk of Bias 2 |

| Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HFFKA) | |||||||

| Amin et al. 2015 [124] | Northeast Region; 2 elementary schools (1442 trays from students in grades 3-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | Spring 2012 and Spring 2013 | Policy: HHFKA | Digital imagery, weighed plate waste, and direct observation | Selection: The policy was associated with a significant increase in FV selection (97.5% vs. 84.3%; p < 0.001). Consumption: The policy was associated with slightly lower FV consumption (0.51 cups vs. 0.45 cups, p < 0.01) | High |

| Bontranger Yoder et al. 2015 [78] | WI; 11 elementary schools (7117 trays from students in grades 3–5) | Cross-sectional and Pre/post (no comparison group) * * For Policy only | 2010 to 2013 |

| Digital imagery | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The intervention components (i.e., nutrition education, taste tests, and other activities) were not associated with differences in F/V consumption. There was no change in consumption before or after implementation of the HHFKA. | High |

| Cohen et al. 2014 [24] | MA; 4 elementary/K-8 schools (1030 students in grades 3–8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | Fall 2011 and Fall 2012 | Policy: HHFKA + removal of chocolate milk | Weighed plate waste | Selection: The HHFKA was associated with a 23% increase in the percent of students selecting a fruit (p < 0.0001). There was no association with vegetable selection. Milk selection decreased by 24.7% (p < 0.0001) when chocolate milk was removed. Consumption: The HHFKA was associated with increased entrée consumption (15.6% increase; p < 0.0001) and vegetable consumption (16.2% increase; p < 0.0001). Milk consumption decreased by 10% when chocolate milk was removed (p < 0.0001). There was no impact on fruit consumption. | Low |

| Cullen et al. 2015B [26] | TX; 8 elementary schools (1045 trays from students in grades | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | Spring 2011 & Spring 2013 | Policy: HHFKA | Visual estimation | Selection: After implementing the HHFKA, a significantly greater proportion of students selected fruit (17.8% percentage point increase); p < 0.001) and whole grains (67.4% percentage point increase; p < 0.001). There was no association with overall vegetable selection. Consumption: The HHFKA was associated with a decrease in milk consumption (61.1% vs. 78.8% consumed; p < 0.01). There was no association with total fruit, total vegetable, or whole grain consumption among those who selected the meal component. | Low |

| Ishdorj et al. 2015 [98] | Texas; 3 elementary schools (students in grades K-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | Spring 2012 and Fall 2012 | Policy: HHFKA | Aggregate plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The HHFKA was not associated with differences in consumption of entrées or vegetables. | Very High |

| Schwartz et al. 2015 [25] | N.S.; 12 middle schools (students in grades 5–7) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2012, 2013, and 2014 | Policy: HHFKA | Weighed plate waste | Selection: The HHFKA was associated with a significant increase in fruit selection. Consumption: The HHFKA was associated with an increase in vegetable and entrée consumption. There was no association with fruit or milk consumption. | Low |

| Access to Competitive Foods | |||||||

| Cullen et al. 2000 [125] | TX; 4 elementary schools and 1 middle school (594 students in grade 4–5) | Cross-sectional | 1998–1999 | Policy: Access to competitive foods | Lunch food records (student self-report) | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Compared with students who had access to competitive foods, students who did not have access consumed significantly more fruits (0.24 vs. 0.11 servings; p < 0.001) and vegetables (0.54 vs. 0.47 servings; p < 0.05). | High |

| Cullen et al. 2004 [126] | TX; 4 elementary schools and 1 middle school (594 students in grade 4–5) | QE: Pre/post (with comparison group) | 1998–99 to 1999–2000 | Policy: Access to competitive foods | Lunch food records (student self-report) | Selection: Not measured Consumption: When students gained access to competitive foods, they consumed on average significantly fewer servings of fruits, vegetables (excluding high-fat vegetables), and milk. | High |

| Cullen et al. 2006 [129] | Harris County, TX; 3 middle schools (7473 food diaries from students in grades 6–8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2001–02 to 2002–03 | Policy: Local competitive food policy that included the removal of vending machines from inside cafeteria (moved to hallways near the cafeteria by the gyms) and removal of chips, desserts, and SSBs from snack bars (but still available in vending machines) | Lunch food records (student self-report) | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The policy was associated with a significant increase in milk consumption, and a significant decrease in SSB and vegetable consumption. Compensation was observed between a decrease in a la carte sales from the snack bars and an increase from the vending machines (in their new locations). | High |

| Cullen et al. 2008 [128] | TX; 3 middle schools (18,178 food diaries from students in grades 6–8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2001–02, 2002–03, and 2005–06 | Policy: State competitive food policy that restricted the portion size of snacks and SSBs; limited the total fat content of snacks; and limited the frequency of serving high-fat vegetables (i.e., French fries) to ≤3 times per week | Lunch food records (student self-report) | Selection: Not measured Consumption: The policy was associated with greater school meal consumption of vegetables and milk. It was also associated with a decrease in competitive foods (i.e., SSB and snack chips). | High |

| Ishdorj et al. 2013 [110] | Nationally representative sample (SNDA-III); 256 schools (2096 students) | Cross-sectional | 2004–05 |

| 24 h recall | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Policies that place restrictions on the sales of competitive foods were associated with greater fruit consumption. Policies that restrict desserts were associated with greater vegetable consumption. Policies that limited French fries were associated with lower fruit consumption. Limiting whole and 2% milk was associated with greater fruit and vegetable consumption. Nutrition education and policies that increase the amount of fresh fruit and vegetable available daily at lunch policies were not associated with consumption of fruits or vegetables. | High |

| Marlette et al. 2005 [127] | Frankfort, KY; 3 middle schools (743 students in grade 6) | Cross-sectional | 2002 | Policy: Competitive Foods. When competitive foods are available, the impact of purchasing snacks on meal consumption was assessed | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Students who purchased competitive foods consumed on average significantly less fruits, grains, meats, and mixed dished from their school lunch compared with students with only a school lunch. | Low |

| Other Local Policies | |||||||

| Canterberry et al. 2017 [133] | New Orleans, LA; 7 elementary schools with 3 food service providers (18,070 trays from students in grades 4 and 5) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2014 | Policy: A local policy exceeded the HHFKA and included more fresh, less processed ingredients including: fresh/frozen F/V; more whole grains; no mechanically separated meat or animal by-products; no processed cheese with additives/fillers; and no deep-fried foods | Weighed plate waste | Selection: Not measured Consumption: On average, there were lower school meal consumption rates among the intervention schools, although this was primarily driven by low consumption rates with one of the food service providers. With another food service provider, there were no significant differences in consumption between the intervention schools and control schools. | Low |

| Cohen et al. 2012 [56] | Boston, MA; 4 middle schools (3049 students in grades 3–8) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2009 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: The intervention was associated with a 51% increase in whole grain selection (p = 0.02). Consumption: Students in the intervention schools, consumed 0.36 more servings of vegetables per day (p = 0.01) compared with students in control schools. There was no impact on milk, fruit, or whole grain consumption. | Low |

| Cohen et al. 2014 [24] | MA; 4 elementary/K-8 schools (1030 students in grades 3–8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | Fall 2011 and Fall 2012 | Policy: HHFKA + removal of chocolate milk | Weighed plate waste | Selection: The HHFKA was associated with a 23% increase in the percent of students selecting a fruit (p < 0.0001). There was no association with vegetable selection. Milk selection decreased by 24.7% (p < 0.0001) when chocolate milk was removed. Consumption: The HHFKA was associated with increased entrée consumption (15.6% increase; p < 0.0001) and vegetable consumption (16.2% increase; p < 0.0001). Milk consumption decreased by 10% when chocolate milk was removed (p < 0.0001). There was no impact on fruit consumption. | Low |

| Farris et al. 2019 [132] | VA; 7 elementary schools (1813 breakfasts from students in grades PK-5) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) | 2014–15 | Policy: Breakfast in the classroom | Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: Breakfast in the classroom was associated with decreased overall food waste (43.0% to 38.5%), including decreases for entrée items, juice, and savory snack foods (p < 0.01). | High |

| Hanks et al. 2014 [130] | OR + Midwest and Eastern Regions: 25 elementary schools (students in grades K-5) | QE: Post-only (with comparison group) | 2010–11 to 2011–12 | Policy: Removal of chocolate milk | Aggregate waste and Visual estimation | Selection: When chocolate milk was removed, 90.1% of sales were replaced with white milk. Consumption: Milk waste was higher in schools that did not have chocolate milk compared with schools that did have chocolate milk. | High |

| Schwartz et al. 2018 [131] | New England region; 2 K-8 schools (13,883 trays from students in grades K-8) | QE: Pre/post (no comparison group) and Post-only (no comparison group) * *For Policy only | 2010–11 to 2012–13 |

| Weighed plate waste | Selection: Significantly fewer students selected milk when juice was available. There was approximately a 20 percentage point increase in milk selection in the second year of the policy compared with the in the first year. Consumption: Among students who selected milk, milk consumption was lower in the second year of the policy compared with in the first year. On days when juice was offered, students consumed significantly less milk (at both time points). | High |

| Young et al. 2013 [47] | N.S.; 1 middle school (3810 trays from students in grades 6–8) | Cross-Sectional | 2011–12 | Policy: A new wellness policy required schools to implement the practices below:

| Visual estimation | Selection: Not measured Consumption: After exposure to the wellness policy for over a semester, students consumed significantly more fruits and cooked vegetables. | High |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Agriculture. National School Lunch Program. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/child-nutrition-programs/national-school-lunch-program.aspx (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Food Research and Action Center (FRAC). Facts: National School Lunch Program. Available online: https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/cnnslp.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Briefel, R.R.; Crepinsek, M.K.; Cabili, C.; Wilson, A.; Gleason, P.M. School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, S91–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture. National School Lunch Program: Total Participation. 2020. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/01slfypart-2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Public Law 111-296, 124 Stat, 3183; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- United States Department of Agriculture. National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program. In Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in School as Required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Fed Regist; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 81, pp. 50131–50151. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Local School Wellness Policy Implementation Under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Final Rule. Fed Regist; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 81, p. 50151. [Google Scholar]

- Niaki, S.F.; Moore, C.E.; Chen, T.-A.; Cullen, K.W. Younger elementary school students waste more school lunch foods than older elementary school students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capps, O., Jr.; Ishdorj, A.; Murano, P.S.; Storey, M. Examining vegetable plate waste in elementary schools by diversity and grade. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2016, 3, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Watson, K.B.; Fithian, A.R. The impact of school socioeconomic status on student lunch consumption after implementation of the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. J. Sch. Health 2009, 79, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Richardson, S.; Austin, S.B.; Economos, C.D.; Rimm, E.B. School lunch waste among middle school students: Nutrients consumed and costs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, L.; Tripurana, M.; Englund, T.; Bergman, E.A. Food group preferences of elementary school children participating in the National School Lunch Program. J. Child Nutr. Manag. 2010, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.H.; Gerson, D.; Porter, K.; Petrillo, J. A study of school lunch food choice and consumption among elementary school students. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 2015, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, L. The importance of exposure for healthy eating in childhood: A review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 20, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O. Fourth-grade children’s consumption of fruit and vegetable items available as part of school lunches is closely related to preferences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Herrera, M.L.; Cooke, L.; Gibson, E.L. Modifying children’s food preferences: The effects of exposure and reward on acceptance of an unfamiliar vegetable. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, L.R.; Lourenco, S.; Hansen, G.L.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Schofield, C. Choice architecture as a means to change eating behaviour in self-service settings: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrestal, S.; Cabili, C.; Dotter, D.; Logan, C.W.; Connor, P.; Boyle, M.; Enver, A.; Nissar, H. School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study. In School Meal Program Operations and School Nutrition Environments; Final Report Volume 1; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.F.; Jahn, J.L.; Richardson, S.; Cluggish, S.A.; Parker, E.; Rimm, E.B. Amount of time to eat lunch is associated with children’s selection and consumption of school meal entrée, fruits, vegetables, and milk. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nutrition Education in US Schools. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/school_nutrition_education.htm (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Hunsberger, M.; McGinnis, P.; Smith, J.; Beamer, B.A.; O’Malley, J. Elementary school children’s recess schedule and dietary intake at lunch: A community-based participatory research partnership pilot study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, M.; Lane, H. Evaluation of the offer vs. serve option within self-serve, choice menu lunch program at the elementary school level. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1989, 89, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziose, M.M.; Ang, I.Y.H. Peer reviewed: Factors related to fruit and vegetable consumption at lunch among elementary students: A scoping review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.; Richardson, S.; Parker, E.; Catalano, P.J.; Rimm, E.B. Impact of the new US Department of Agriculture school meal standards on food selection, consumption, and waste. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.B.; Henderson, K.E.; Read, M.; Danna, N.; Ickovics, J.R. New school meal regulations increase fruit consumption and do not increase total plate waste. Child. Obes. 2015, 11, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Chen, T.-A.; Dave, J.M. Changes in foods selected and consumed after implementation of the new National School Lunch Program meal patterns in southeast Texas. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M.K.; Gearan, E.; Cabili, C.; Dotter, D.; Niland, K.; Washburn, L.; Paxton, N.; Olsho, L.; LeClair, L.; Tran, V. Student participation, satisfaction, plate waste, and dietary intakes. In School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study; 2019; Volume 4, final report; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support: Alexandria, VA, USA; Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/SNMCS-Volume2.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Cadario, R.; Chandon, P. Which healthy eating nudges work best? A meta-analysis of field experiments. Mark. Sci. 2020, 39, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.; Dynan, L.; Siegel, R. Healthier choices in school cafeterias: A systematic review of cafeteria interventions. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, G.J.; Price, J.; Sosa, F.A. Behavioral economic approaches to influencing children’s dietary decision making at school. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano-Olivier, M.I.; Horne, P.J.; Viktor, S.; Erjavec, M. Using nudges to promote healthy food choices in the school dining room: A systematic review of previous investigations. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.J.; Ellison, B.; Hamdi, N.; Richardson, R.; Prescott, M.P. A systematic review of school meal nudge interventions to improve youth food behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumby, S.; Leineweber, M.; Andrade, J. The impact the smarter lunchroom movement strategies have on school children’s healthy food selection and consumption: A systematic review. J. Child Nutr. Manag. 2018, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, J.R.; Lyford, C.P. Behavioral economics in the school lunchroom: Can it affect food supplier decisions? A systematic review. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Boehme, J.S.; Logomarsino, J.V. Reducing food waste and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in schools. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2017, 4, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawson, K.; Rainville, A.J. Salad bars in schools and fruit and vegetable selection and consumption: A review of recent research. J. Child Nutr. Manag. 2019, 43, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Cohen, J.F.; Hecht, A.A.; McLoughlin, G.M.; Turner, L.; Schwartz, M.B. Universal school meals and associations with student participation, attendance, academic performance, diet quality, food security, and body mass index: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Cohort Studies; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luchini, C.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J. Meta-Anal. 2017, 5, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.-L.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]