Main Factors Influencing Whole Grain Consumption in Children and Adults—A Narrative Review

Abstract

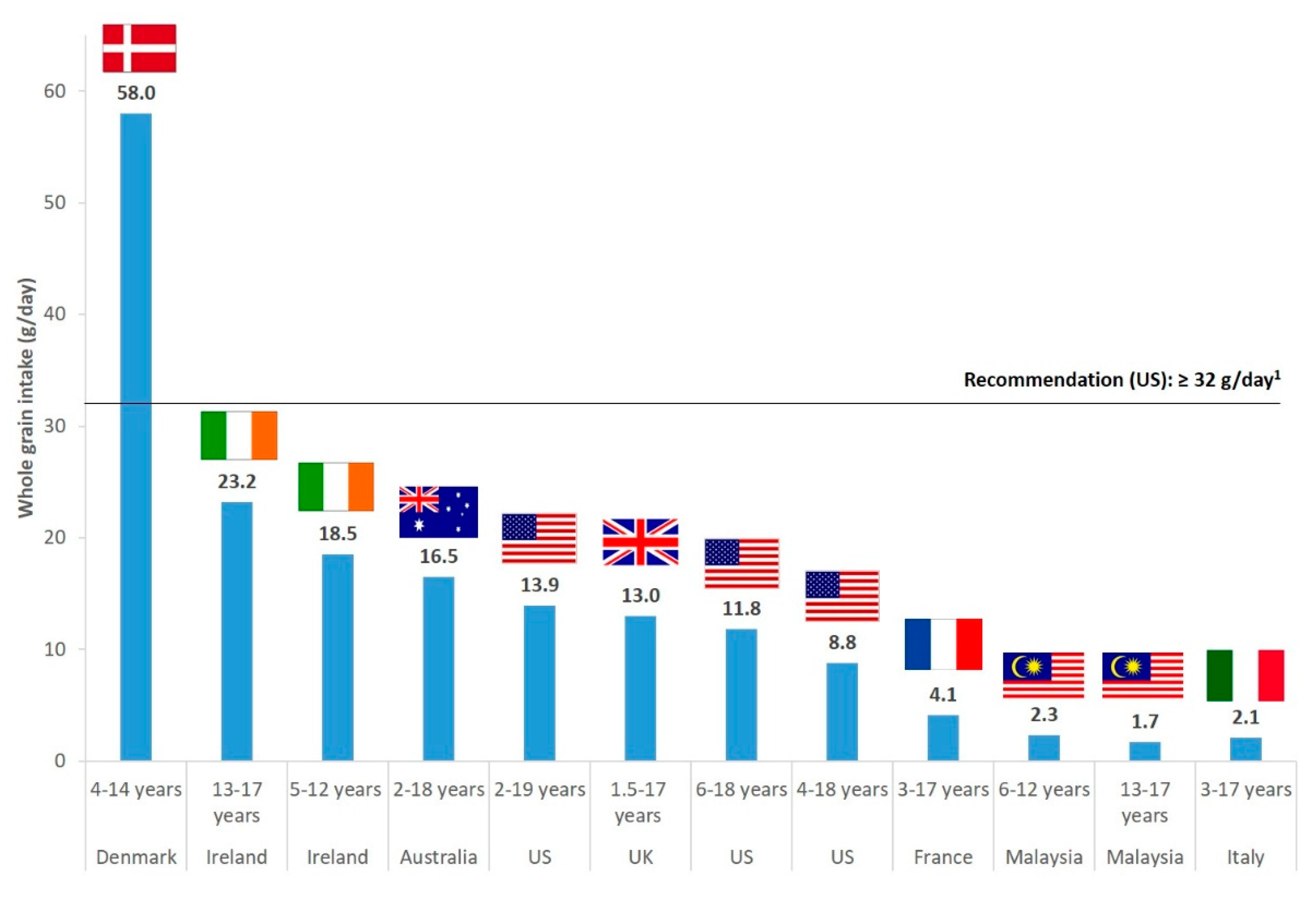

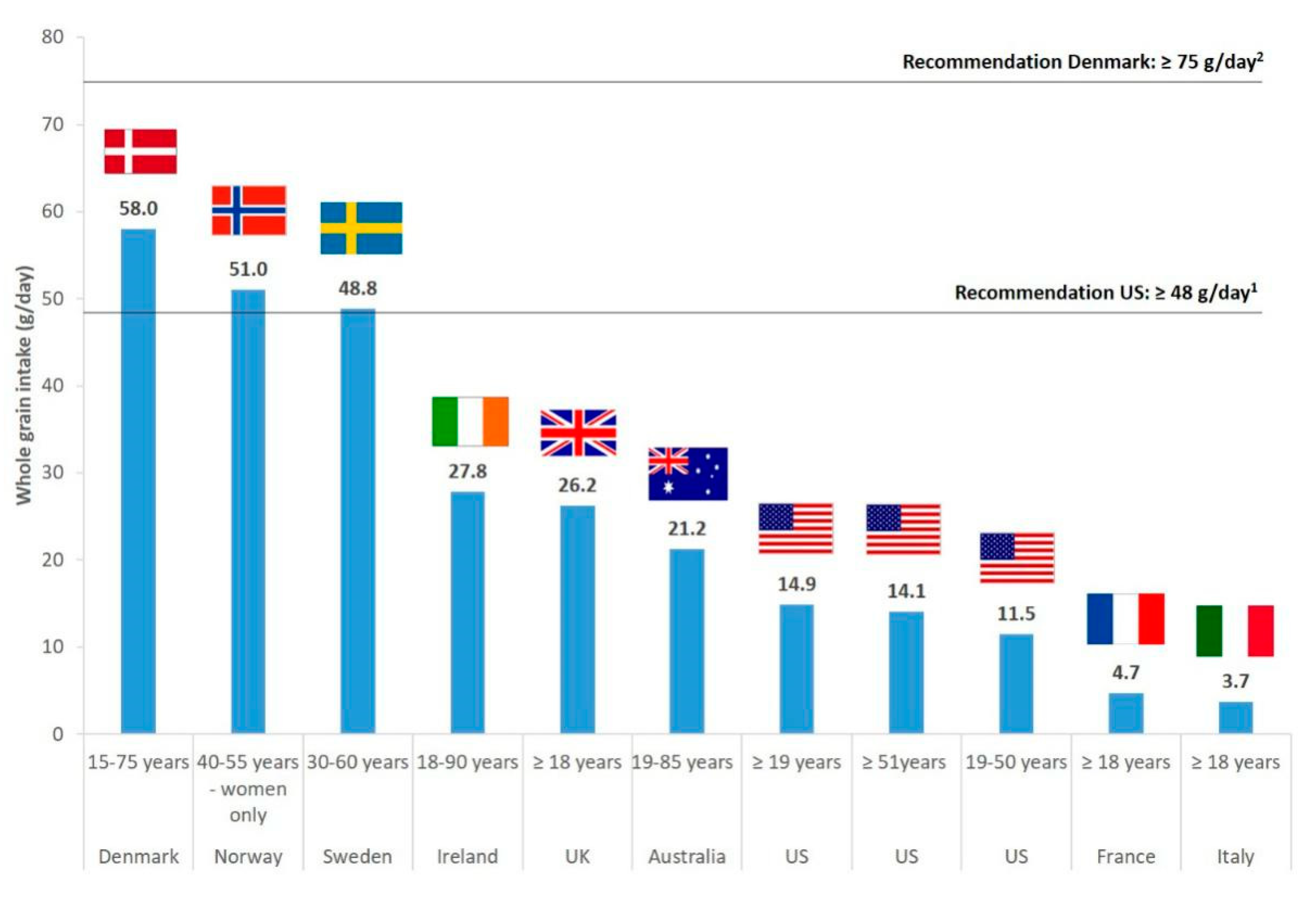

1. Introduction

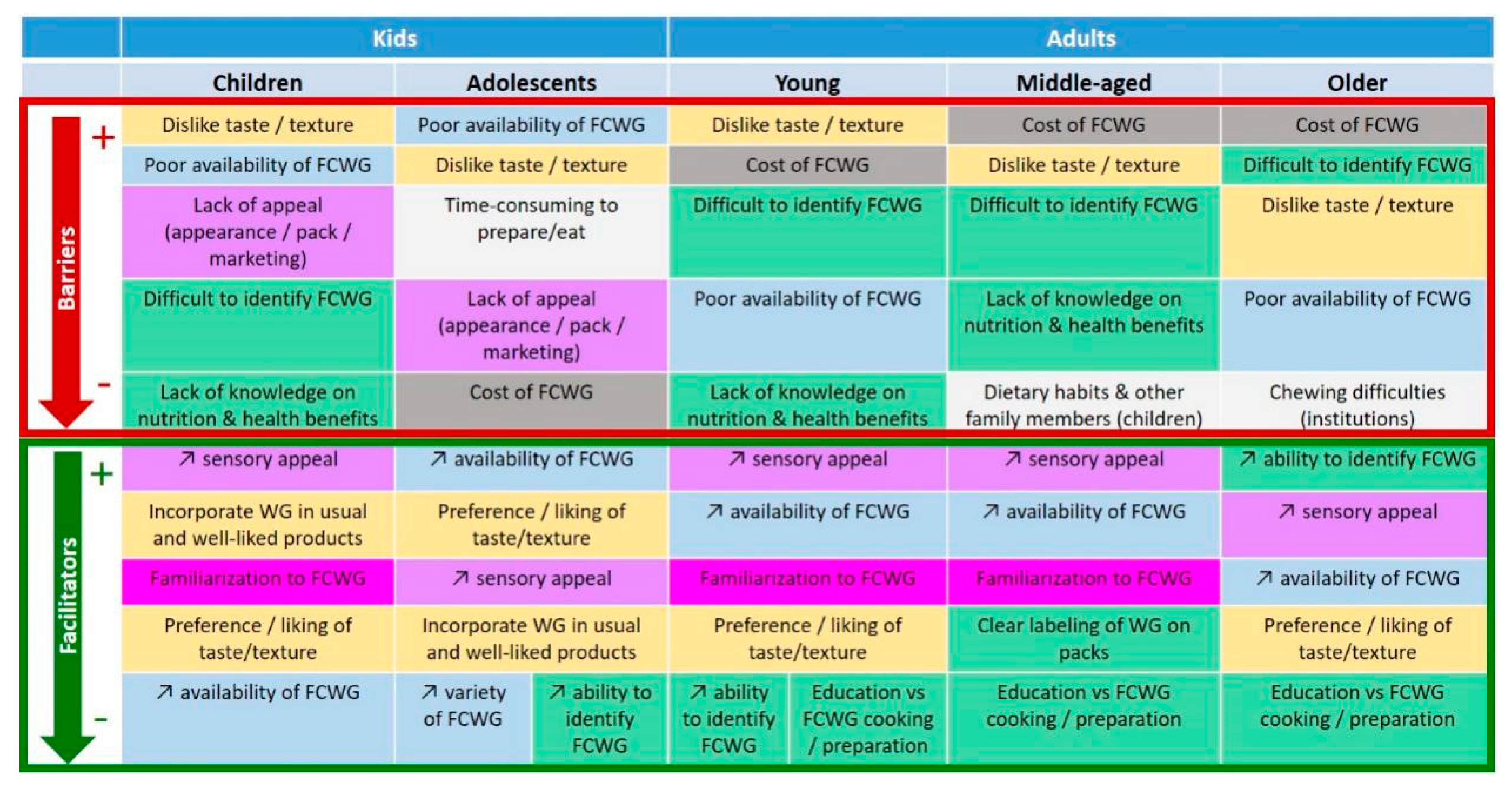

2. Main Barriers to and Facilitators of Whole Grain Consumption

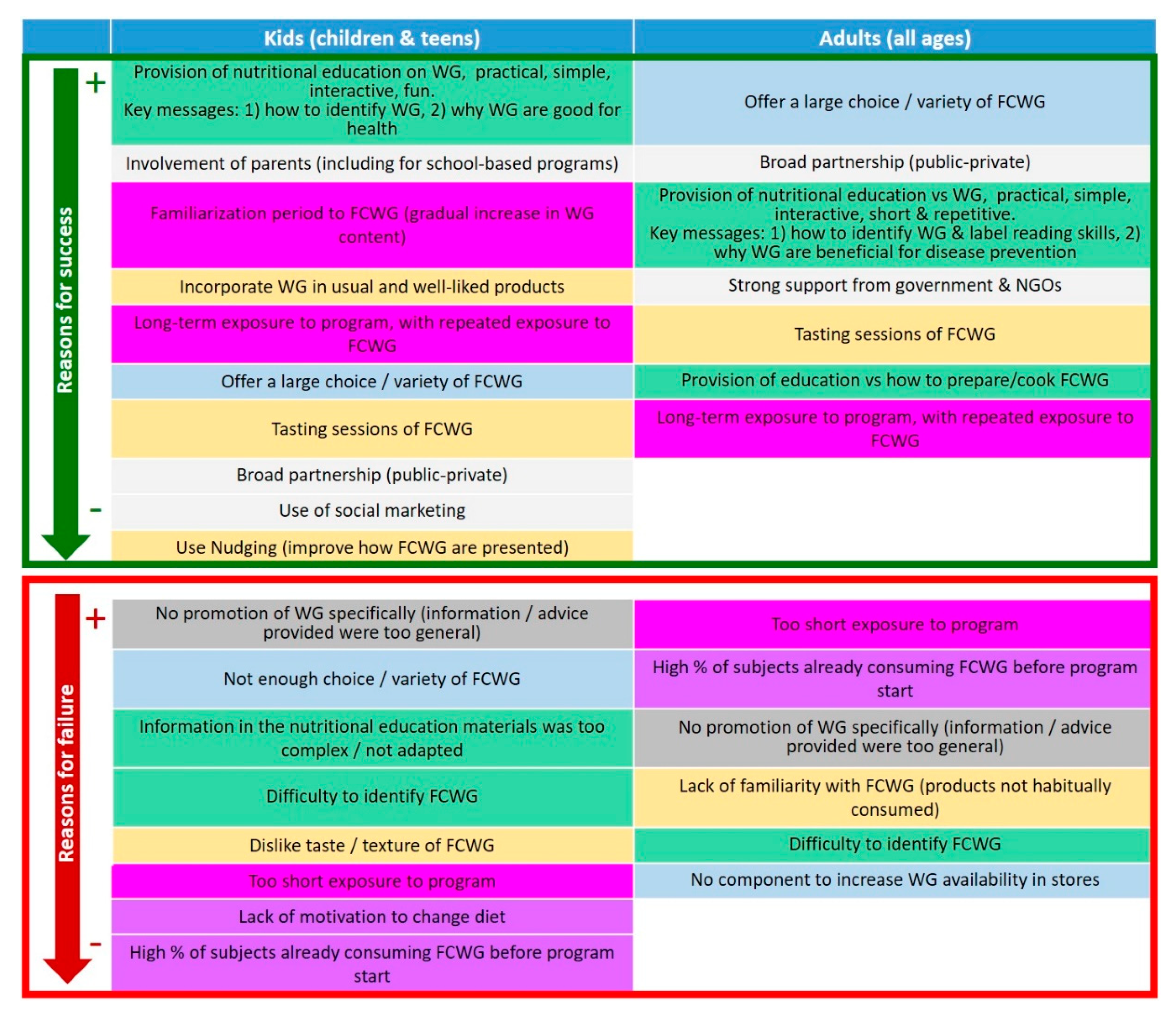

3. Main Reasons for Success and Failure in Programs to Promote WG Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aune, D.; Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Boffetta, P.; Greenwood, D.C.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J.; Riboli, E.; Norat, T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2016, 353, i2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanson-Rolle, A.; Meynier, A.; Aubin, F.; Lappi, J.; Poutanen, K.; Vinoy, S.; Braesco, V. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Human Studies to Support a Quantitative Recommendation for Whole Grain Intake in Relation to Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, C.J.; Nugent, A.P.; Tee, E.S.; Thielecke, F. Whole-grain dietary recommendations: The need for a unified global approach. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2031–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.; Tucker, M.; Harriman, C.; Honnalagadda, S.S. Whole Grains: Definition, Dietary Recommendations, and Health Benefits. Cereal Foods World 2013, 58, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services; US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed.; 2015. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide—Helping You Eat a Healthy, Balanced Diet. September 2018 v4.; 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/742750/Eatwell_Guide_booklet_2018v4.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Ministry of Health of Brazil; Secretariat of Health Care; Primary Health Care Department. Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population 2014. 2014. Translated from Portuguese to English by Carlos Augusto Monteiro. Available online: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/guia_alimentar_populacao_ingles.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Santé publique France. Recommendations Concerning Diet, Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour for Adults. 2019. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/determinants-de-sante/nutrition-et-activite-physique/documents/rapport-synthese/recommandations-relatives-a-l-alimentation-a-l-activite-physique-et-a-la-sedentarite-pour-les-adultes (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Indian National Institute of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Indians—A Manual. 2011. Available online: https://www.nin.res.in/downloads/DietaryGuidelinesforNINwebsite.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Health Canada. Canada’s Dietary Guidelines for Health Professionals and Policy Makers. 2019. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide. 2019. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/?utm_source=canada-ca-foodguide-en&utm_medium=vurl&utm_campaign=foodguide (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Danish Veterinary and Food Administration [Fødevarestyrelsen]. The Official Dietary Guidelines [De officielle kostråd] (in Danish). 2013. Available online: https://altomkost.dk/raad-og-anbefalinger/de-officielle-kostraad/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Norwegian Directorate of Health [Helsedirektoratet]. Recommendations about Diet, Nutrition and Physical Activity [Anbefalinger om Kosthold, Ernæring og Fysisk Aktivitet] (in Norwegian). 2014. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/anbefalinger-om-kosthold-ernaering-og-fysisk-aktivitet/Anbefalinger%20om%20kosthold%20ern%C3%A6ring%20og%20fysisk%20aktivitet.pdf/_/attachment/inline/2f5d80b2-e0f7-4071-a2e5-3b080f99d37d:2aed64b5b986acd14764b3aa7fba3f3c48547d2d/Anbefalinger%20om%20kosthold%20ern%C3%A6ring%20og%20fysisk%20aktivitet.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Swedish Food Agency [Livsmedelsverket]. Find Your Way to Eat Greener, not too much and Be Active. 2015. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/sweden/en/ (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Arvola, A.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Dean, M.; Vassallo, M.; Winkelmann, M.; Claupein, E.; Saba, A.; Shepherd, R. Consumers’ beliefs about whole and refined grain products in the UK, Italy and Finland. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Champoux, T.; Marquart, L.; Vickers, Z.; Reicks, M. Perceptions of children, parents, and teachers regarding whole-grain foods, and implications for a school-based intervention. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2006, 38, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffman, M.A.; Camire, M.E. Perceived Barriers to Increased Whole Grain Consumption by Older Adults in Long-Term Care. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 36, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejborn, H.; Hess Ygil, K.; Fagt, S.; Trolle, E.; Christensen, T.; Division of Nutrition National Food Institute Technical University of Denmark. Danskernes fuldkornsindtag 2011–2013 [Wholegrain intake of Danes 2011–2013]. DTU Fødevareinstituttet 2014, 4. (In Danish). Available online: https://www.food.dtu.dk/-/media/Institutter/Foedevareinstituttet/Publikationer/Pub-2014/Danskernes_fuldkornsindtag_2011-2013.ashx (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Devlin, N.F.; McNulty, B.A.; Gibney, M.J.; Thielecke, F.; Smith, H.; Nugent, A.P. Whole grain intakes in the diets of Irish children and teenagers. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, L.M.; Beck, E.J.; Probst, Y.C.; Cashman, C.J. Whole grain intake of Australians estimated from a cross-sectional analysis of dietary intake data from the 2011–13 Australian Health Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, K.D.; Pearce, M.S.; McKevith, B.; Thielecke, F.; Seal, C.J. Low whole grain intake in the UK: Results from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey rolling programme 2008–11. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2015–2016, Individuals 2 Years and over (Excluding Breast-Fed Children), Day 1 Dietary Intake Data, Weighted. Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED) 2015–2016. Table 1c. Grains: Mean Amounts of Food Patterns Ounce Equivalents Consumed per Individual, by Gender and Age, in the United States, 2015–2016. 2020. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/fped/Table_1_FPED_GEN_1516.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Albertson, A.M.; Reicks, M.; Joshi, N.; Gugger, C.K. Whole grain consumption trends and associations with body weight measures in the United States: Results from the cross sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2012. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, C.R.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Devareddy, L. Ten-year trends in fiber and whole grain intakes and food sources for the United States population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2010. Nutrients 2015, 7, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellisle, F.; Hebel, P.; Colin, J.; Reye, B.; Hopkins, S. Consumption of whole grains in French children, adolescents and adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, N.; Koo, H.C.; Hamid Jan, J.M.; Mohd Nasir, M.T.; Tan, S.Y.; Appukutty, M.; Nurliyana, A.R.; Thielecke, F.; Hopkins, S.; Ong, M.K.; et al. Whole Grain Intakes in the Diets Of Malaysian Children and Adolescents--Findings from the MyBreakfast Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, S.; D’Addezio, L.; Piccinelli, R.; Hopkins, S.; Le Donne, C.; Ferrari, M.; Mistura, L.; Turrini, A. Intakes of whole grain in an Italian sample of children, adolescents and adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyro, C.; Skeie, G.; Dragsted, L.O.; Christensen, J.; Overvad, K.; Hallmans, G.; Johansson, I.; Lund, E.; Slimani, N.; Johnsen, N.F.; et al. Intake of whole grain in Scandinavia: Intake, sources and compliance with new national recommendations. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, C.B.; Devlin, N.F.; Buffini, M.; Walton, J.; Flynn, A.; Gibney, M.J.; Nugent, A.P.; McNulty, B.A. Whole grain intakes in Irish adults: Findings from the National Adults Nutrition Survey (NANS). Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, K.D.; Pearce, M.S.; McKevith, B.; Thielecke, F.; Seal, C.J. Whole grain intake and its association with intakes of other foods, nutrients and markers of health in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey rolling programme 2008–11. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Champoux, T.L.; Rosen, R.; Marquart, L.; Reicks, M. The development of psychosocial measures for whole-grain intake among children and their parents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Burgess-Champoux, T.; Vickers, Z.; Reicks, M.; Marquart, L. White Whole-Wheat Flour Can Be Partially Substituted for Refined-Wheat Flour in Pizza Crust in School Meals without Affecting Consumption. J. Child Nutr. Manag. Publ. Sch. Nutr. Assoc. 2008. Available online: http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/08spring/chan/index.asp (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Chu, Y.L.; Warren, C.A.; Sceets, C.E.; Murano, P.; Marquart, L.; Reicks, M. Acceptance of two US Department of Agriculture commodity whole-grain products: A school-based study in Texas and Minnesota. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1380–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delk, J.; Vickers, Z. Determining a series of whole wheat difference thresholds for use in a gradual adjustment intervention to improve children’s liking of whole-wheat bread rolls. J. Sens. Stud. 2007, 22, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmer, A.; Hausner, H.; Reinbach, H.C.; Bredie, W.L.; Wendin, K. Acceptance of Nordic snack bars in children aged 8–11 years. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 10484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahns, L.; McDonald, L.; Wadsworth, A.; Morin, C.; Liu, Y.; Nicklas, T. Barriers and facilitators to following the Dietary Guidelines for Americans reported by rural, Northern Plains American-Indian children. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklas, T.A.; Jahns, L.; Bogle, M.L.; Chester, D.N.; Giovanni, M.; Klurfeld, D.M.; Laugero, K.; Liu, Y.; Lopez, S.; Tucker, K.L. Barriers and facilitators for consumer adherence to the dietary guidelines for Americans: The health study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.A.; Burgess-Champoux, T.L.; Marquart, L.; Reicks, M.M. Associations between whole-grain intake, psychosocial variables, and home availability among elementary school children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, L.; Marquart, L. Whole grain snack intake in an after-school snack program: A pilot study. J. Foodserv. 2009, 20, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, L.; Marquart, L. Consumption of graham snacks in afterschool snack programs based on whole grain flour content. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldavini, J.; Crawford, P.; Ritchie, L.D. Nutrition claims influence health perceptions and taste preferences in fourth- and fifth-grade children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritt, A.; Reicks, M.; Marquart, L. Reformulation of pizza crust in restaurants may increase whole-grain intake among children. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1407–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, M.; Evans, C.; Hugh-Jones, S. Factors influencing adolescent whole grain intake: A theory-based qualitative study. Appetite 2016, 101, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M.; Burgess-Champoux, T. Whole-grain intake correlates among adolescents and young adults: Findings from Project EAT. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohjanheimo, T.; Luomala, H.; Tahvonen, R. Finnish adolescents’ attitudes towards wholegrain bread and healthiness. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford, A.; Langkamp-Henken, B.; Hughes, C.; Christman, M.C.; Jonnalagadda, S.; Boileau, T.W.; Thielecke, F.; Dahl, W.J. Whole-grain intake in middle school students achieves dietary guidelines for Americans and MyPlate recommendations when provided as commercially available foods: A randomized trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisanz, K.J.; Stanek Krogstrand, K.L. Consumption & Attitudes about Whole Grain Foods of UNL Students Who Dine in a Campus Cafeteria. Rural. Rev. Undergrad. Res. Agric. Life Sci. 2007, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Combest, S.; Warren, C. Perceptions of college students in consuming whole grain foods made with Brewers’ Spent Grain. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, E.J.; Caine-Bish, N. Interactive introductory nutrition course focusing on disease prevention increased whole-grain consumption by college students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mohanraj, R.; Sudha, V.; Wedick, N.M.; Malik, V.; Hu, F.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Mohan, V. Perceptions about varieties of brown rice: A qualitative study from Southern India. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalis, R.M.; Giovanni, M.; Silliman, K. Whole grain foods: Is sensory liking related to knowledge, attitude, or intake? Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 46, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellette, T.; Yerxa, K.; Therrien, M.; Camire, M.E. Whole Grain Muffin Acceptance by Young Adults. Foods 2018, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialon, V.S.; Clark, M.R.; Leppard, P.I.; Cox, D.N. The effect of dietary fibre information on consumer responses to breads and “English” muffins: A cross-cultural study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, J.E.; Brownlee, I.A. Wholegrain Food Acceptance in Young Singaporean Adults. Nutrients 2017, 9, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, A.; Omary, M.B.; Rosentrater, K.A.; Arndt, E.A.; Prasopsunwattana, N.; Chongcham, S.; Flores, R.A.; Lee, S.P. Understanding Consumer Preference for Functional Barley Tortillas Through Sensory, Demographic, and Behavioral Data. Cereal Chem. 2008, 85, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.W.; Hesse, D.; Arndt, E.; Marquart, L. Knowledge and practices of school foodservice personnel regarding whole grain foods. J. Foodserv. 2009, 20, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, M.; Marquart, L. Factors Influencing Whole-grain Intake by Health Club Members. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 20, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellyer, E.N.; Fraser, I.; Haddock-Fraser, J. Implicit measurement of consumer attitudes towards whole grain products. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1330–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhihi, A.; Gimbi, D.; Njelekela, M.; Shemaghembe, E.; Mwambene, K.; Chiwanga, F.; Malik, V.S.; Wedick, N.M.; Spiegelman, D.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Consumption and acceptability of whole grain staples for lowering markers of diabetes risk among overweight and obese Tanzanian adults. Glob. Health 2013, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Yousey, L.; Barno, T.; Caskey, M.; Asche, K.; Reicks, M. Whole-grain continuing education for school foodservice personnel: Keeping kids from falling short. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Kumar, S.; Holmes, M.D.; Spiegelman, D.; Lin, X.; Hu, F.B. Substituting brown rice for white rice to lower diabetes risk: A focus-group study in Chinese adults. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Johnson, M.A.; Fischer, J.G.; Hargrove, J.L. Nutrition and health education intervention for whole grain foods in the Georgia older Americans nutrition programs. J. Nutr. Elder. 2005, 24, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNab, L.R.; Davis, K.; Francis, S.L.; Violette, C. Whole Grain Nutrition Education Program Improves Whole Grain Knowledge and Behaviors Among Community-Residing Older Adults. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 36, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violette, C.; Kantor, M.A.; Ferguson, K.; Reicks, M.; Marquart, L.; Laus, M.J.; Cohen, N. Package Information Used by Older Adults to Identify Whole Grain Foods. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 35, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznesof, S.; Brownlee, I.A.; Moore, C.; Richardson, D.P.; Jebb, S.A.; Seal, C.J. WHOLEheart study participant acceptance of wholegrain foods. Appetite 2012, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMackin, E.; Dean, M.; Woodside, J.V.; McKinley, M.C. Whole grains and health: Attitudes to whole grains against a prevailing background of increased marketing and promotion. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, A.; Vickers, Z. Consumer liking of refined and whole wheat breads. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, S473–S480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T. Promoting cereal grain and whole grain consumption: An Australian perspective. Cereal Chem. 2010, 87, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, L.; Pham, A.T.; Lautenschlager, L.; Croy, M.; Sobal, J. Beliefs about whole-grain foods by food and nutrition professionals, health club members, and special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participants/State fair attendees. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1856–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rødbotten, M.; Tomic, O.; Holtekjølen, A.K.; Grini, I.S.; Lea, P.; Granli, B.S.; Grimsby, S.; Sahlstrøm, S. Barley bread with normal and low content of salt; sensory profile and consumer preference in five European countries. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 64, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Sadeghi, L.; Schroeder, N.; Reicks, M.; Marquart, L. Gradual Incorporation of Whole Wheat Flour into Bread Products for Elementary School Children Improves Whole Grain Intake. J. Child Nutr. Manag. A Publ. Sch. Nutr. Assoc. 2008, 32. Available online: https://schoolnutrition.org/5--News-and-Publications/4--The-Journal-of-Child-Nutrition-and-Management/Fall-2008/Volume-32,-Issue-2,-Fall-2008---Rosen;-Sadeghi;-Schroeder;-Reicks;-Marquart/ (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- Keast, D.R.; Rosen, R.A.; Arndt, E.A.; Marquart, L.F. Dietary modeling shows that substitution of whole-grain for refined-grain ingredients of foods commonly consumed by US children and teens can increase intake of whole grains. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, I.A.; Kuznesof, S.A.; Moore, C.; Jebb, S.A.; Seal, C.J. The impact of a 16-week dietary intervention with prescribed amounts of whole-grain foods on subsequent, elective whole grain consumption. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess-Champoux, T.L.; Chan, H.W.; Rosen, R.; Marquart, L.; Reicks, M. Healthy whole-grain choices for children and parents: A multi-component school-based pilot intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudgens, M.E.; Barnes, A.S.; Lockhart, M.K.; Ellsworth, S.C.; Beckford, M.; Siegel, R.M. Small Prizes Improve Food Selection in a School Cafeteria Without Increasing Waste. Clin. Pediatrics 2017, 56, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, A.; Odoms-Young, A.M.; Schiffer, L.A.; Kim, Y.; Berbaum, M.L.; Porter, S.J.; Blumstein, L.B.; Bess, S.L.; Fitzgibbon, M.L. The 18-month impact of special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children food package revisions on diets of recipient families. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshed, A.B.; Davis, S.M.; Greig, E.A.; Myers, O.B.; Cruz, T.H. Effect of WIC Food Package Changes on Dietary Intake of Preschool Children in New Mexico. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2015, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tester, J.M.; Leung, C.W.; Crawford, P.B. Revised WIC Food Package and Children’s Diet Quality. Pediatrics 2016, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, K.; Carlson, J.J.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Eisenmann, J.C.; Paek, H.J.; Betz, H.H.; Thompson, T.; Wen, Y.; Norman, G.J. Project FIT: A School, Community and Social Marketing Intervention Improves Healthy Eating Among Low-Income Elementary School Children. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchla, M.; McCabe, G.P.; Miller, K.B.; Kranz, S. The effect of high fiber snacks on digestive function and diet quality in a sample of school-age children. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Kraak, V.I.; Choumenkovitch, S.F.; Hyatt, R.R.; Economos, C.D. The change study: A healthy-lifestyles intervention to improve rural children’s diet quality. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Slawta, J.; Bentley, J.; Smith, J.; Kelly, J.; Syman-Degler, L. Promoting healthy lifestyles in children: A pilot program of be a fit kid. Health Promot. Pract. 2008, 9, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawta, J.N.; DeNeui, D. Be a Fit Kid: Nutrition and physical activity for the fourth grade. Health Promot. Pract. 2010, 11, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kleef, E.; Vrijhof, M.; Polet, I.A.; Vingerhoeds, M.H.; de Wijk, R.A. Nudging children towards whole wheat bread: A field experiment on the influence of fun bread roll shape on breakfast consumption. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerenhouts, D.; Deriemaeker, P.; Hebbelinck, M.; Clarys, P. Energy and macronutrient intake in adolescent sprint athletes: A follow-up study. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.; Smit, L.A.; Parker, E.; Austin, S.B.; Frazier, A.L.; Economos, C.D.; Rimm, E.B. Long-term impact of a chef on school lunch consumption: Findings from a 2-year pilot study in Boston middle schools. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, D.M.; Moag-Stahlberg, A.; Ellis, K.; Vandewater, E.A.; Malkani, R. Evaluation of a student participatory, low-intensity program to improve school wellness environment and students’ eating and activity behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppu, U.; Lehtisalo, J.; Kujala, J.; Keso, T.; Garam, S.; Tapanainen, H.; Uutela, A.; Laatikainen, T.; Rauramo, U.; Pietinen, P. The diet of adolescents can be improved by school intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, K.L.; Bandini, L.G.; Folta, S.C.; Wansink, B.; Eliasziw, M.; Must, A. Impact of a Smarter Lunchroom intervention on food selection and consumption among adolescents and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a residential school setting. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, G.; Bakhshi, S.; Surujlal-Harry, A.; Stasinopoulos, M.; Baker, A. A computerised tailored intervention for increasing intakes of fruit, vegetables, brown bread and wholegrain cereals in adolescent girls. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affenito, S.G.; Thompson, D.; Dorazio, A.; Albertson, A.M.; Loew, A.; Holschuh, N.M. Ready-to-eat cereal consumption and the School Breakfast Program: Relationship to nutrient intake and weight. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, E.M.; Crepinsek, M.K.; Fox, M.K. School meals: Types of foods offered to and consumed by children at lunch and breakfast. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, S67–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Chen, T.A.; Dave, J.M. Changes in foods selected and consumed after implementation of the new National School Lunch Program meal patterns in southeast Texas. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastorini, C.M.; Lykou, A.; Yannakoulia, M.; Petralias, A.; Riza, E.; Linos, A. The influence of a school-based intervention programme regarding adherence to a healthy diet in children and adolescents from disadvantaged areas in Greece: The DIATROFI study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Blumenthal, S.J.; Hoffnagle, E.E.; Jensen, H.H.; Foerster, S.B.; Nestle, M.; Cheung, L.W.; Mozaffarian, D.; Willett, W.C. Associations of food stamp participation with dietary quality and obesity in children. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Tester, J.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C. SNAP Participation and Diet-Sensitive Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S127–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejborn, H.; Hess Ygil, K.; Fagt, S.; Trolle, E.; Christensen, T.; Division of Nutrition National Food Institute Technical University of Denmark. Wholegrain intake of Danes 2011–2012. DTU Fødevareinstituttet 2013, 2. Available online: https://www.food.dtu.dk/english/-/media/Institutter/Foedevareinstituttet/Publikationer/Pub-2013/Rapport_Fuldkornsindtag_11-12_UK.ashx?la=da&hash=8B2A20C3ED33A0B8564E5403DFD8225CB25EE42D (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Arts, J.; English, C.; Greene, G.W.; Lofgren, I.E. A Nutrition Intervention to Increase Whole Grain Intake in College Students. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 31, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoms-Young, A.M.; Kong, A.; Schiffer, L.A.; Porter, S.J.; Blumstein, L.; Bess, S.; Berbaum, M.L.; Fitzgibbon, M.L. Evaluating the initial impact of the revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food packages on dietary intake and home food availability in African-American and Hispanic families. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, S.E.; Ritchie, L.D.; Spector, P.; Gomez, J. Revised WIC food package improves diets of WIC families. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Mazier, M.J. Knowledge, perceptions, and consumption of whole grains among university students. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. A Publ. Dietit. Can./Revue Canadienne de la Pratique et de la Recherche en Dietetique Une Publication des Dietetistes du Canada 2013, 74, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinch-Nielsen, N.; Neess, R.I. Public Private Partnership to Promote Whole Grain Consumption. In Proceedings of the Whole Grains Summit 2012 (Cereal Foods World PLEXUS/43—AACC International), Minneapolis, MN, US, 20–22 May 2012; Available online: https://www.aaccnet.org/publications/plexus/cfwplexus/library/books/Documents/WholeGrainsSummit2012/CPLEX-2013-1001-20B.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Suthers, R.; Broom, M.; Beck, E. Key Characteristics of Public Health Interventions Aimed at Increasing Whole Grain Intake: A Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Issuing Organization and Year | Age Range | Quantitative Recommendation (Recommended Quantities in Amounts of WG Ingredients) | Qualitative Recommendation (Statement) | Source of Identified Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | USDHHS/USDA 2015 (DGA 2015) | Whole population ≥ 2 y | ≥3 oz-eq 1/2000 kcal | Consume at least half of all grains as WG. | [5] |

| UK | PHE 2018 | Whole population | None | Choose WG versions/varieties. | [6] |

| Brazil | Ministry of Health 2014 | Whole population ≥ 2 y | None | Make natural or minimally processed foods the basis of your diet. | [7] |

| France | Santé publique France 2019 | Adults | At least one WG starch per day (no information vs. corresponding quantity of WG ingredients) | Starches can be consumed every day. It is recommended to consume the WG version when they are grain-based: WG bread, WG rice, WG pastas, etc. | [8] |

| India | Indian National Institute of Nutrition 2011 | Whole population | None | Use a combination of WG, grams (pulses) and greens. Increase consumption of WG. | [9] |

| Canada | Health Canada 2019 | Whole population ≥ 2 y | None | WG should be consumed regularly. Eat plenty of WG food. Choose WG foods. | [10,11] |

| Denmark | Danish Veterinary and Food Administration 2013 | Whole population | ≥75 g/d | Choose WG first—it’s easy if you look for the WG logo when you shop. | [12] |

| Norway | Norwegian Directorate of Health 2014 | Whole population ≥ 1 y | 70–90 g/d | Eat WG cereal products every day. | [13] |

| Sweden | Swedish Food Agency 2015 | Whole population ≥ 2 y | 70 g/d in females—90 g/d in males | Choose WG varieties when you eat pasta, bread, grain and rice. | [14] |

| Country | Program Name 1 | Setting 2 | Age Group(s) 3 | Was the Program Focused on WG? 4 | Components Used to Promote WG 5 | Target(s) 6 | Efficacy of the Program to Improve WG Intakes 7 | Program Type 8 | Study References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | WIC Food package (2009 revision) | Home | Children (preschoolers) | No | Federal aid program including provision of supplemental foods within the WIC Food package; since 2009, at least 50% of cereal products in the package are WG | Children & their mothers—low income | Neutral | Gov. (federal aid program) | [76,77,78] |

| USA | Power Plate | School | Older children | No | Use of emoticons + small prizes as incentives to select healthy foods such as a WG entrée | Children | Neutral | Academic | [75] |

| USA | Power of 3: Get healthy with WG foods | School | Older children | Yes | Classroom education lessons; school cafeteria menu changes to ↑ avail. of WG (for a variety of foods); family-oriented activities | Children & parents | Favorable | Academic | [74] |

| USA | FIT | School & community | Older children | No | Multicomponent initiative with school (e.g., interactive nutrition education, food tasting) & social marketing elements + community input—but nothing specific to WG | Children, parents, teachers, rep from community-based org. & school district | Favorable for WG bread; neutral for WG cereals (not further defined) | Mix (academic, public & private) | [79] |

| USA | CHANGE | School & community | Older children | No | Offering WG daily in school cafeteria menus + school education + parent & community components | Children, parents, teachers & school staff | Neutral | Private (NGO) | [81] |

| USA | Be a Fit Kid | School | Older children | No | Food tasting & nutrition education + parents meeting | Children & parents | Favorable | Academic | [82,83] |

| USA | Brauchla 2013 | School | Older children | No (fiber) | Offering large variety of high-fiber snacks (mostly WG) at school | Children | Favorable | Academic & industrial | [80] |

| USA | Rosen 2008 | School | Older children | Yes | Gradual incorporation of WG flour in bread products, burritos & chocolate chip cookies served at school meals | Children | Favorable | Academic & industrial | [71] |

| NL | Van Kleef 2014 | School | Older children | Yes | Nudging (use of fun shape for WG breads) | Children | Favorable | Academic | [84] |

| USA | FUTP60 | School | Adolescents | No | Social marketing + web-based support system for implementation of wellness policy—but nothing specific to WG | Children, teachers, school staff & parents | Favorable | Private | [87] |

| USA | Smarter lunch room | School | Adolescents with intellectual disabilities | No | Change from white to WG bread in peanut butter & jelly sandwiches + nudging (changes in how foods are presented & served) | Children | Favorable | Academic | [89] |

| USA | The Chef initiative | School | Adolescents | No | Training of school cafeteria staff with a professional chef to learn how to prepare healthy (incl. substitution of RG with WG) & palatable school lunches | Children & school food service staff | Inconclusive | Private (NGO) | [86] |

| USA | Radford 2014 | School & home | Adolescents | Yes | Provision for FREE of a large variety of commercially available WG-containing foods at home and WG-containing snacks at school | Children | Favorable | Academic & industrial | [46] |

| Belgium | Aerenhout 2011 | Home | Adolescents (athletes) | No | Non-stringent advice sent by email to consume more WG bread | Children & parents | Favorable for girls, neutral for boys (WG bread) | Academic | [85] |

| Finland | Hoppu 2010 | School | Adolescents | No | Nutritional education as part of normal teaching and change in quality of snacks served at school—but nothing specific to WG | Children, parents, teachers, school food service staff, school heads | Favorable for girls, neutral for boys (rye bread) | Academic | [88] |

| UK | Rees 2010 | School | Adolescents | No | Information leaflet tailored to each subject (according to answers to a baseline diet & psychological questionnaire)—no info vs. content related to WG | Children | Favorable for brown bread, neutral for WG breakfast cereals | Public (FSA) | [90] |

| USA | SNAP | Home | All ages | No | Federal aid program that provides money for food supply—but nothing specific to WG | Children & their families—low income | Neutral | Gov. (federal aid program) | [95,96] |

| USA | NSMP | School | Older children & adolescents | No | Before 2012: nothing; 2012–2014: 50% of grain foods served at school meals must be WG-rich (>50% WG ingredients); since 2014: 100% | School meal officers & children | Favorable following 2012 revisions; neutral before 2012 revisions | Gov. (federal aid program) | [91,92,93] |

| USA | Keast 2011 | Food industries | Older children & adolescents | Yes | Modest change in food formulation to ↑ WG content in foods that are commonly consumed | Industrials | Favorable (modeling study only) | Industrial | [72] |

| Denmark | Fuldkorn (The Danish WG Partnership) | National campaign (home & food industries/bakers) | All ages | Yes | ↑ in WG content of several commercial food products, use of WG logo on foods with high content in WG, communication to improve consumer knowledge vs. WG, information materials to assist bakers and retailers => broad partnership with involvement of multiple stakeholders | Overall population & industrials | Favorable (large ↗) | Mixed (gov. & industrial) | [18,97] |

| Greece | DIATROFI | School | All ages | No | Provision of WG-containing foods in school meals, nutritional education material distributed to children & families, health promotion events for children & parents (incl. chef demonstrations) | Children & parents from disadvantaged areas | Favorable | Academic | [94] |

| Country | Program name 1 | Setting 2 | Age & Sex (% Women) Group(s) 3 | Was the Program Focused on WG? 4 | Components Used to Promote WG 5 | Target(s) 6 | Efficacy of the Program to Improve WG Intakes 7 | Program Type 8 | Study References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | Williams 2013 | University | Young (college students) (both; 87%) | No | Introductory nutrition course (1 semester), with no particular focus on WG | College students | Inconclusive | Academic | [101] |

| USA | Ha 2011 | University | Young (college students) (both; 88%) | No | Interactive introductory nutrition course (1 semester), focusing on disease prevention with 4h on WG-related topics (examples of interactive activities: food label hunt, WG tasting) | College students | Favorable | Academic | [49] |

| USA | Arts 2016 | University | Young (college students) (both; 78%) | Yes (+ low-fat dairy) | Delivery of WG nutrition education messages on the Point-of Selection (POS) sites in dining halls and by email/text messages (daily during 3 wks) (and same for low-fat dairy) | College students | Neutral | Academic | [98] |

| USA | WIC Food package (2009 revision) | Home | Young (pregnant/post-partum women, mothers of 5y-children) (100%) | No | Federal aid program including provision of supplemental foods within the WIC Food package; since 2009, at least 50% of cereal products in the package are WG | Pregnant or post-partum women, or mothers of 5y- children | Neutral for objective measure, favorable for self-perceived consumption (6 & 18 mo after implementation of revision) | Gov. (federal aid program) | [76,99,100] |

| USA | Croy 2005 | Not specified | Middle-aged (health club members, frequent consumers of WG) (100%) | Yes | Interactive educational program with four 60/90-min weekly meetings (topics/activities: health benefits of WG, info & strategies to identify WG & read labels, supermarket tour, WG bread tasting) | Adults | Favorable | Academic | [57] |

| USA | Power of 3: Get healthy with WG foods | Home & community | Middle-aged (parents of 9–11y children) (both; 91%) | Yes | Interactive educational program with family-oriented activities (weekly newsletters, classroom lessons vs. WG definition & identification, baking & grocery store tours with a “hunt for WG”, tasting of WG-containing foods) (over 5 mo) | Parents (and their children) | Neutral | Academic | [74] |

| USA | Is it Whole Grain? | Community 9 | Older (community-dwelling) (both; 89%) | Yes | Interactive educational program with hands-on activities and tasting of WG-containing foods (three 1-h weekly sessions, with delivery of worksheets, informational handouts, recipes) (topics: WG definition & identification, WG health benefits) | Older adults themselves | Favorable | Academic | [63] |

| USA | Whole Grains and Your Health Program (part of the “Georgia Older Americans Nutrition Program”) | Institution (centers for seniors) | Older (resident in centers for seniors, and attending a congregate meal program) (both; 88%) | Yes | Educational program (5 lessons with delivery of handouts) (topics: WG definition & identification, WG health benefits, tips vs. how to include WG in the diet/cook WG) (1 to 2 lessons/mo over a period of 5 to 6 mo) | Older adults themselves | Neutral | Academic | [62] |

| Denmark | Fuldkorn | National campaign (home & food industries/bakers) | All ages (general population) (both; 53%) | Yes | ↑ in WG content of several commercial food products, use of WG logo on foods with high content in WG, communication to improve consumer knowledge vs. WG, information materials to assist bakers and retailers => broad partnership with involvement of multiple stakeholders + organization of special campaigns targeted at specific groups (e.g., young men -> WG communication in cafes, night clubs…, and on internet and social media) | Overall population (including adults of all ages) & industrials | Favorable (large ↗ for all adults, and for men and women separately) | Mixed (gov. & industrial) | [18,97,102] |

| UK | WHOLEheart study10 | Home | Young & middle-aged (healthy overweight adults with low habitual WG intakes)(both; 52%) | Yes | 16-week WG familiarization period requiring participants to consume 60–120 g WG ingredients/d (a wide variety of WG-containing foods was provided free of charge to participants, from which they could self-select their preferred foods) | Adults | Favorable (elective WG consumption 1y after the end of the familiarization period) | Academic | [73] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meynier, A.; Chanson-Rollé, A.; Riou, E. Main Factors Influencing Whole Grain Consumption in Children and Adults—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082217

Meynier A, Chanson-Rollé A, Riou E. Main Factors Influencing Whole Grain Consumption in Children and Adults—A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020; 12(8):2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082217

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeynier, Alexandra, Aurélie Chanson-Rollé, and Elisabeth Riou. 2020. "Main Factors Influencing Whole Grain Consumption in Children and Adults—A Narrative Review" Nutrients 12, no. 8: 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082217

APA StyleMeynier, A., Chanson-Rollé, A., & Riou, E. (2020). Main Factors Influencing Whole Grain Consumption in Children and Adults—A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 12(8), 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082217