Vitamin D Supplementation and Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Review Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Results of Included Studies

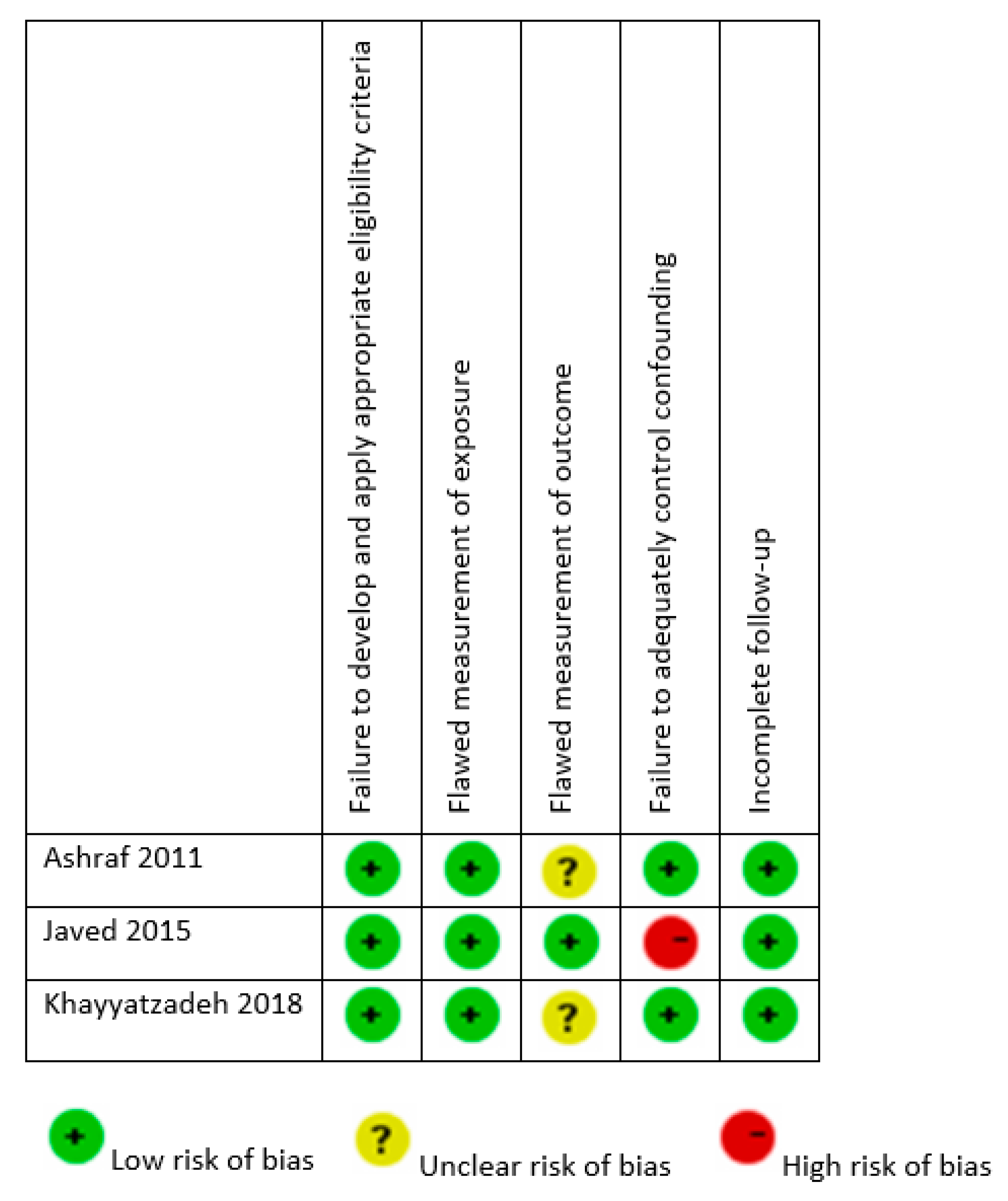

3.4. Assessment of Risk of Bias

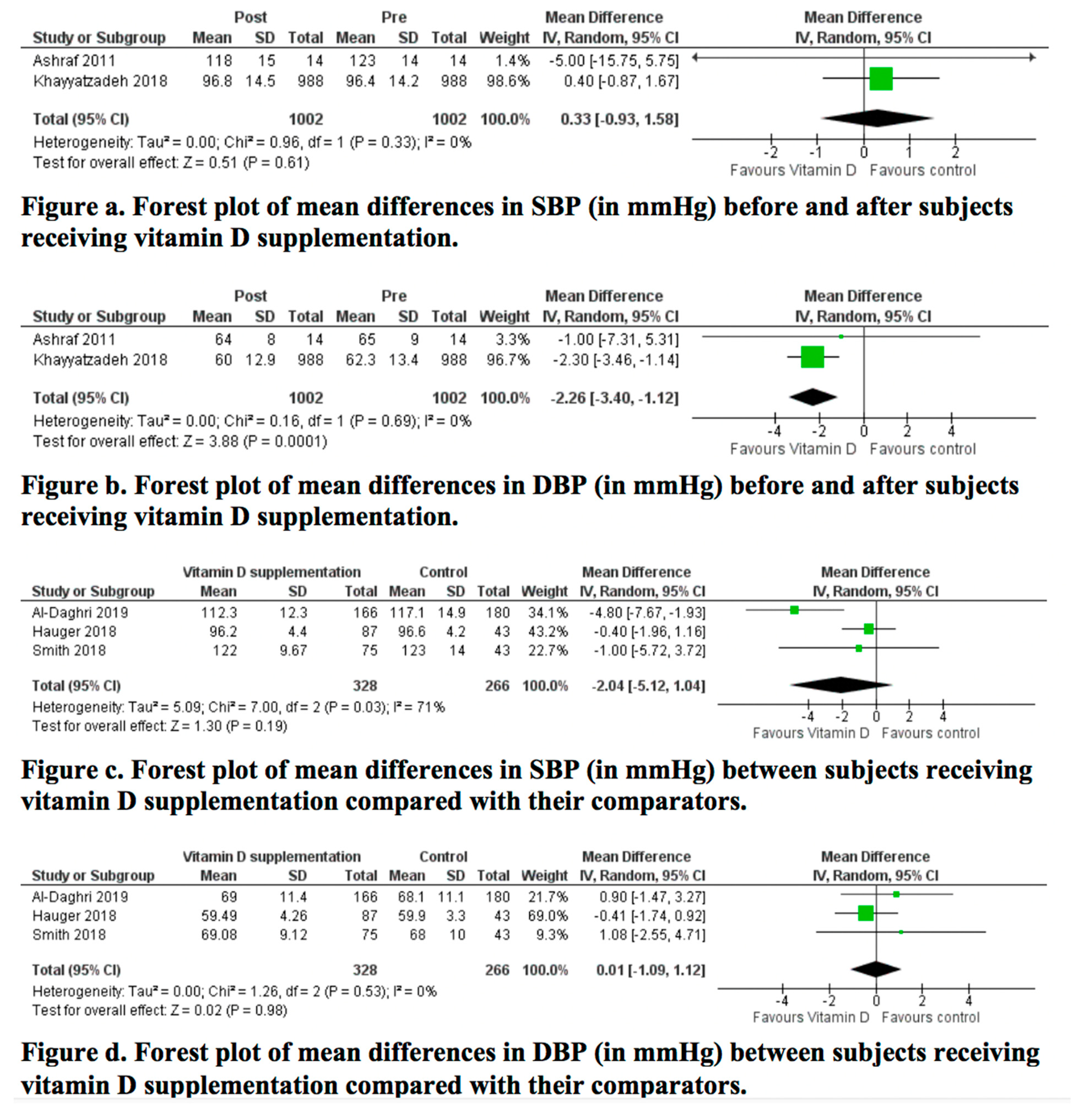

3.5. Results of the Meta-Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouillon, R.; Marcocci, C.; Carmeliet, G.; Bikle, D.; White, J.H.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lips, P.; Munns, C.F.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Giustina, A.; et al. Skeletal and Extraskeletal Actions of Vitamin D: Current Evidence and Outstanding Questions. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 1109–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, E.M.; Lewis, R.D. New Concepts in Vitamin D Requirements for Children and Adolescents: A Controversy Revisited. Front. Horm. Res. 2018, 50, 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio, S.; Di Nisio, A.; Mele, C.; Scappaticcio, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; Obesity Programs of nutrition, E.R.; Assessment, G. Obesity and hypovitaminosis D: Causality or casualty? Int. J. Obes. Suppl. 2019, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Chen, T.C. Vitamin D deficiency: A worldwide problem with health consequences. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1080S–1086S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absoud, M.; Cummins, C.; Lim, M.J.; Wassmer, E.; Shaw, N. Prevalence and predictors of vitamin D insufficiency in children: A Great Britain population based study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parva, N.R.; Tadepalli, S.; Singh, P.; Qian, A.; Joshi, R.; Kandala, H.; Nookala, V.K.; Cheriyath, P. Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and Associated Risk Factors in the US Population (2011–2012). Cureus 2018, 10, e2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubo, Y.; Iwashima, Y. Higher Blood Pressure as a Risk Factor for Diseases Other Than Stroke and Ischemic Heart Disease. Hypertension 2015, 66, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiu, A.C.; Bishop, M.D.; Asico, L.D.; Jose, P.A.; Villar, V.A.M. Primary Pediatric Hypertension: Current Understanding and Emerging Concepts. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zha, M.; Zhu, Y.; Rahimi, K.; Rudan, I. Global Prevalence of Hypertension in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 2019, 173, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, L.A.; Rosner, B.; Roche, A.F.; Guo, S. Serial Changes in Blood Pressure from Adolescence into Adulthood. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 135, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V.; Agarwal, S. Does Vitamin D Deficiency Lead to Hypertension? Cureus 2017, 9, e1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.Y.; Park, K.M.; Lee, M.J.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.-Y. Vitamin D and Hypertension. Electrolyte Blood Press. E BP 2017, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, J.P.; Williams, J.S.; Fisher, N.D. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in humans. Hypertension 2010, 55, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinsky, D.H.; Armstrong, S.; Mangarelli, C.; Kemper, A.R. The association between vitamin D and cardiometabolic risk factors in children: A systematic review. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 2013, 52, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, K.-T.; Abidi, N.; Ranasinha, S.; Brown, J.; Rodda, C.; McCallum, Z.; Zacharin, M.; Simm, P.J.; Magnussen, C.G.; Sabin, M.A. Low vitamin D is associated with hypertension in paediatric obesity. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, A.W. From vitamin D to hormone D: Fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 491s–499s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, J.A.; Davies, J.I.; Witham, M.D.; Morris, A.D.; Struthers, A.D. Vitamin D improves endothelial function in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and low vitamin D levels. Diabet. Med. 2008, 25, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarcin, O.; Yavuz, D.G.; Ozben, B.; Telli, A.; Ogunc, A.V.; Yuksel, M.; Toprak, A.; Yazici, D.; Sancak, S.; Deyneli, O.; et al. Effect of vitamin D deficiency and replacement on endothelial function in asymptomatic subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 4023–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleithoff, S.S.; Zittermann, A.; Tenderich, G.; Berthold, H.K.; Stehle, P.; Koerfer, R. Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Pollock, N.; Stallmann-Jorgensen, I.S.; Gutin, B.; Lan, L.; Chen, T.C.; Keeton, D.; Petty, K.; Holick, M.F.; Zhu, H. Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in adolescents: Race, season, adiposity, physical activity, and fitness. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Trials. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.com (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Montori, V.; Akl, E.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence--study limitations (risk of bias). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.P.; Alvarez, J.A.; Gower, B.A.; Saenz, K.H.; McCormick, K.L. Associations of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and components of the metabolic syndrome in obese adolescent females. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2011, 19, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, A.; Kullo, I.J.; Balagopal, P.B.; Kumar, S. Effect of vitamin D3 treatment on endothelial function in obese adolescents. Pediatric Obes. 2016, 11, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyatzadeh, S.S.; Mirmoosavi, S.J.; Fazeli, M.; Abasalti, Z.; Avan, A.; Javandoost, A.; Rahmani, F.; Tayefi, M.; Hanachi, P.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. High-dose vitamin D supplementation is associated with an improvement in several cardio-metabolic risk factors in adolescent girls: A nine-week follow-up study. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 55, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Amer, O.E.; Khattak, M.N.K.; Sabico, S.; Ghouse Ahmed Ansari, M.; Al-Saleh, Y.; Aljohani, N.; Alfawaz, H.; Alokail, M.S. Effects of different vitamin D supplementation strategies in reversing metabolic syndrome and its component risk factors in adolescents. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 191, 105378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Stallmann-Jorgensen, I.S.; Pollock, N.K.; Harris, R.A.; Keeton, D.; Huang, Y.; Li, K.; Bassali, R.; Guo, D.H.; Thomas, J.; et al. A 16-week randomized clinical trial of 2000 international units daily vitamin D3 supplementation in black youth: 25-hydroxyvitamin D, adiposity, and arterial stiffness. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 4584–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelishadi, R.; Salek, S.; Salek, M.; Hashemipour, M.; Movahedian, M. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk factors in children with metabolic syndrome: A triple-masked controlled trial. J. Pediatr. 2014, 90, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.J.; Tripkovic, L.; Hauger, H.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Molgaard, C.; Lanham-New, S.A.; Hart, K.H. Winter Cholecalciferol Supplementation at 51 degrees N Has No Effect on Markers of Cardiometabolic Risk in Healthy Adolescents Aged 14-18 Years. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauger, H.; Molgaard, C.; Mortensen, C.; Ritz, C.; Frokiaer, H.; Smith, T.J.; Hart, K.; Lanham-New, S.A.; Damsgaard, C.T. Winter Cholecalciferol Supplementation at 55 degrees N Has No Effect on Markers of Cardiometabolic Risk in Healthy Children Aged 4-8 Years. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauger, H.; Laursen, R.P.; Ritz, C.; Mølgaard, C.; Lind, M.V.; Damsgaard, C.T. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiometabolic outcomes in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, L.A.; Struthers, A.D.; Khan, F.; Jorde, R.; Scragg, R.; Macdonald, H.M.; Alvarez, J.A.; Boxer, R.S.; Dalbeni, A.; Gepner, A.D.; et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Incorporating Individual Patient Data. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Ho, S.C.; Zhong, L. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure. South. Med J. 2010, 103, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Huang, K. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure parameters in patients with vitamin D deficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. JASH 2018, 12, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witham, M.D.; Nadir, M.A.; Struthers, A.D. Effect of vitamin D on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Burgess, S.; Munroe, P.B.; Khan, H. Vitamin D and high blood pressure: Causal association or epiphenomenon? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What clinicians need to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, C.F.; Shaw, N.; Kiely, M.; Specker, B.L.; Thacher, T.D.; Ozono, K.; Michigami, T.; Tiosano, D.; Mughal, M.Z.; Makitie, O.; et al. Global Consensus Recommendations on Prevention and Management of Nutritional Rickets. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.L.; Greer, F.R. Prevention of Rickets and Vitamin D Deficiency in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldowney, S.; Lucey, A.J.; Hill, T.R.; Seamans, K.M.; Taylor, N.; Wallace, J.M.; Horigan, G.; Barnes, M.S.; Bonham, M.P.; Duffy, E.M.; et al. Incremental cholecalciferol supplementation up to 15 mug/d throughout winter at 51–55 degrees N has no effect on biomarkers of cardiovascular risk in healthy young and older adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, M.; Liu, X.; Fayet-Moore, F.; Brock, K.E.; Papandreou, D.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Mason, R.S. Effects of Vitamin D Status and Supplements on Anthropometric and Biochemical Indices in a Clinical Setting: A Retrospective Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossini, M.; Gatti, D.; Viapiana, O.; Fracassi, E.; Idolazzi, L.; Zanoni, S.; Adami, S. Short-term effects on bone turnover markers of a single high dose of oral vitamin D(3). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E622–E626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year | Study Design | Geographic Setting | Study Population | Age (Years) and Gender | Intervention | Duration | Daily Dose Equivalent | Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashraf, 2011 [25] | Before/after study | Birmingham, USA | 14 obese post-menarchal female adolescents (13 African American, 1 Caucasian American), with serum 25OHD < 75 nmol/L Mean BMI (SD) in kg/m2: NR | Mean (SD) Pre-treatment: 14.9 (1.8) Post-treatment: 15.6 (1.7) | Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol, orally, 50,000 IU), once per week | 8 weeks | 7142.8 IU | NR |

| % Male: 0% | ||||||||

| Javed, 2015 [26] | Before/after study | Rochester, USA | 19 obese adolescents (89.5% non-Hispanic white), non-hypertensive, with serum 25OHD < 75 nmol/L Mean BMI (SD) in kg/m2: deficient: 21.2 (4.4); insufficient: 20.6 (3.6) | Range: 13–18 Mean (SD): 15.8 (1.7) | Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol, 2 pills, 50,000 IU each; Total: 100,000 IU), once per month | 12 weeks | 3278.7 IU | 100% |

| % Male: NR | ||||||||

| Khayyatzadeh, 2018 [27] | Before/after study | Mashhad and Sabzevar, Iran | 940 healthy female adolescents, not taking medications or vitamin D supplements Mean BMI (SD) in kg/m2: 21.07 (4.2) | Range: 12–18 Deficient: 14.5 (1.53) Insufficient: 14.7 (1.51) Sufficient: 15.2 (1.53) | Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol, 1 capsule, 50,000 IU), once per week | 9 weeks | 7142.8 IU | NR dropout rate: 4.8% |

| % Male: 0% |

| Author, Year | Study Design | Geographic Setting | Study Population | Age (Years) and Gender | Intervention | Duration | Daily Dose Equivalent | Control | Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Daghri, 2019 [28] | Cluster RCT | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 535 healthy children and adolescents with 25OHD < 50 nmol/L, non-hypertensive, not taking medications or vitamin supplements Mean BMI (SD) in kg/m2: Total: 23.0 (6.2); Tablet: 23.0 (6.2); Milk: 23.7 (5.6); C: 24.3 (6.4) | Range: 12-18 Mean (SD): Total: 14.9 (1.9) Tablet: 14.3 (1.6) Milk: 14.4 (1.5) C: 16.1 (1.9) | Tablet: n = 166; vitamin D tablet, 1000 IU daily | 24 weeks | Tablet: 1000 IU Milk: 80 IU | n = 180; no intervention | Tablet: 91.1%Milk: 90.4% C: 86.7% |

| % Male: 45.4% | Milk: n = 189; 200 mL of vitamin D-fortified milk, 40 IU/100 mL, daily | ||||||||

| Dong, 2010 [29] | Open-label, investigator-blinded RCT | Richmond, USA | 44 healthy black (African American) adolescents, non-hypertensive, not taking medications or vitamin supplements Mean (SD) BMI percentile: I: 67.8 (30.9); C: 61.6 (33.4) (p = 0.53) | Range: 14–18 Mean (SD): Total: 16.3 (1.4) I: 16.5 (1.4)C: 16.3 (1.1) (p = 0.95) | n = 25; vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), 2000 IU/day | 16 weeks | 2000 IU | n = 24; vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol); 400 IU/day | I: 85% C: 88% (p = 0.65) |

| % Male: 55.5% | |||||||||

| Hauger, 2018 [21] | Double blind, placebo controlled RCT | Copenhagen, Denmark | 119 healthy white children of European origin, not taking vitamin D supplement for ≥1 month prior to the study and not planning a winter sun vacation Normal weight: I1: 90%; I2: 92%; C: 66% | Range: 4–8 Mean (SD): Total: 6.7 (1.5) I1: 6.9 (1.5) I2: 6.7 (1.4) C: 6.5 (1.5) | I1: n = 44; 10 μg D3 tablet/day | 20 weeks | I1: 400 IU I2: 800 IU | n = 43; placebo-matching tablet (0 μg D3/day) | I1: 97.6% I2: 97.6% |

| % Male: 36% | I2: n = 43; 20 μg D3 tablet/day | ||||||||

| Kelishadi, 2014 [30] | Triple blind, placebo controlled RCT | Isfahan, Iran | 43 children and adolescents with metabolic syndrome and BMI ≥3 Z-scores, not taking medication or supplementation use, free of other chronic disease Mean BMI (SD) in kg/m2: C: 27.81(1.04); I: 28.08 (1.06) | Range 10–16 | n = 21; 300,000 IU vitamin D3, 1 capsule/week | 12 weeks | 42,857 IU | n = 22; placebo-matching capsule | I: 88% C: 96% from original sample |

| % Male: NR | |||||||||

| Smith, 2018 [31] | Double blind, placebo controlled RCT | United Kingdom | 102 healthy white adolescents, not taking vitamin D supplement or planning a winter sun vacation Normal weight: I1: 80%; I2: 84%; C: 79% | Range: 14–18 Mean (SD): 15.9 (1.4) I1: 16.0 (1.4) I2: 15.9 (1.5) C: 15.9 (1.4) | I1: n = 39; 10 μg D3 tablet/day I2: n = 36; 20 μg D3 tablet/day | 20 weeks | I1: 400 IU I2: 800 IU | C: n = 43; placebo- matching Tablet (0 μg D3/day) | I1: 94.2% I2: 94.4% |

| % Male: 43% |

| Author, Year | Outcomes Evaluated | Mean (SD) Baseline 25OHD (nmol/L) | Mean (SD) Endline 25OHD (nmol/L) | Mean (SD) Baseline BP (mmHg) | Mean (SD) Endline BP (mmHg) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashraf, 2011 [25] | Serum 25OHD: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | 26.4 (10.9) | 63.6 (30.2) (p < 0.001) | SBP: 123 (14) DBP: 65 (9) | SBP: 118 (15) (p: 0.41) DBP: 64 (8) (p: 0.72) | NS change in SBP and DBP |

| SBP and DBP: automated blood pressure cuff appropriate for arm size (number of measurements: NR) | ||||||

| Javed, 2015 [26] | Serum 25OHD: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | 55.9 (12.2) | 86.9 (16.7) (p < 0.001) | NR | NR | NS change in SBP and DBP |

| SBP and DBP: average of 2 measures by aneroid sphygmomanometer with the participant’s arm supported and positioned at the level of the heart taken after >10 minute rest | ||||||

| Khayyatzadeh, 2018 [27] | Serum 25OHD: electrochemi-luminescence | Total: 23.6 (22.04) Deficient: 17.2 (9.4) Insufficient: 60.07 (8.1) Sufficient: 99.5 (22.2) | Total: 90.9 (38.6) (p < 0.001) Deficient: 89.1 (37.7) (p < 0.001) Insufficient: 99.9 (46.9) (p < 0.001) Sufficient: 116.1 (36.6) (p < 0.001) | SBP: Total: 96.4 (14.2) Deficient: 96.6 (14.2) Insufficient: 98.3 (14.3) Sufficient: 98.8 (11.2) | SBP: Total: 96.8 (14.5) (p = 0.63 in adjusted model) Deficient: 97.1 (14.6) (p = 0.48) Insufficient: 98.2 (13.1) (p = 0.77) Sufficient: 95.6 (14.2) (p = 0.05) | Significant reduction in DBP and NS change in SBP |

| SBP and DBP: standard procedure (procedure not detailed) | DBP: Total: 62.3 (13.4) Deficient: 62.5 (13.05) Insufficient: 64.5 (12.8) Sufficient: 66.05 (10.4) | DBP: Total: 60.0 (12.9) (p = 0.03 in adjusted model) Deficient: 60.7 (13.01) (p = 0.005) Insufficient: 60.9 (10.5) (p < 0.001) Sufficient: 61.9 (12.7) (p = 0.002) |

| Author, Year | Outcomes Evaluated | Mean (SD) Baseline 25OHD (nmol/L) | Mean (SD) Endline 25OHD (nmol/L) | Mean (SD) Baseline BP (mmHg) | Mean (SD) Endline BP (mmHg) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Daghri, 2019 [28] | 25OHD: enzyme linked immunosorbent assay | Tablet: 30.8 (9.3) Milk: 31.8 (8.1) C: 29.8 (10.3) (p = 0.46) | Tablet: 41.5 (14.4) Milk: 38.1 (11.9) C: 31.9 (13.8) (p < 0.001) (p = 0.73 between tablet and milk; <0.001 between tablet and C; p < 0.001 between milk and control) | SBP: Tablet: 117.3 (14.4) Milk: 117.9 (14.4) C: 120.9 (14.9) (p = 0.75) | SBP: Tablet: 112.3 (12.3) Milk: 115.3 (16.1) C: 117.1 (14.9) (p = 0.005) (p = 0.44 between tablet and milk; p = 0.004 between tablet and C; p = 0.19 between milk and C) | Significant decrease in SBP in all groups. Between-group significant decrease in favor of the tablet group (p = 0.005) |

| SBP and DBP: average of 2 measures by a conventional mercurial sphygmomanometer taken after a 30-minute rest | DBP: Tablet: 71.9 (11.9) Milk: 73.3 (15.7) C: 72.5 (11.6) (p = 0.50) | DBP: Tablet: 69 (11.4) Milk: 75.6 (15.7) C: 68.1 (11.1) (p < 0.001) (p < 0.001 between tablet and milk; p = 0.94 between tablet and C; p < 0.001 between milk and C) | Significant decrease in DBP in the tablet and control groups. Between-group significant improvement in favor of control (p < 0.001) | |||

| Elevated BP: ≥90th percentile for age, sex and height | Elevated BP: Tablet: 38.9% Milk: 40.7% C: 34.9% | Elevated BP: Tablet: 25.0% (p < 0.001) Milk: 44.4% (NS) C: 24.7% (p < 0.05) | Significant reduction in elevated BP in the tablet and control groups (p < 0.05) | |||

| Dong, 2010 [29] | Plasma 25OHD: enzyme immunoassay | I: 33.1 (8.7) C: 34.0 (10.6) (p = 0.76) | I: 85.7 (30.1) C: 59.8 (18.2) (p < 0.001) | SBPI: 111.3 (10.4) C: 114.9 (7.8) (p = 0.20) | NR | NS change in SBP or DBP over time in the control or intervention groups (p > 0.05) |

| SBP and DBP: average of 3 measures, 2 minutes apart, by a vital signs monitor after a 5-minute rest | DBP I:68.2 (12.3) C: 69.4 (6.5) (p = 0.17) | |||||

| Hauger, 2018 [32] | Serum 25OHD: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | I1: 56.9 (12.7) I2: 58.1 (13.5) C: 55.2 (10.8) | I1: 61.8 (10.6) I2: 75.8 (11.5) C: 31.1 (7.5) (p < 0.001) | SBP: I1: 95.7 (4.6) I2: 96.4 (4.4) C: 97.1 (5.5) | SBP: I1: 95.6 (4.4) I2: 96.9 (4.4) C: 96.6 (4.2) (NS) | NS change in SBP or DBP when adjusted for baseline value of the outcome |

| Marginally higher DBP of 1.4 mmHg (95% CI: −0.0,2.8; p = 0.05) in I1 compared with I2 | ||||||

| SBP and DBP: average of 2 out of 3 readings, 10 minutes apart, by an automated monitor in a supine position | DBP: I1: 58.8 (4.1) I2: 59.9 (4.6) C: 59.2 (4.1) | DBP: I1: 58.5 (4.5) I2: 60.5 (3.8) C: 59.9 (3.3) (NS) | Marginally lower DBP of −1.2mmHg (95% CI: −2.7, −0.0; p = 0.05) in I1 compared with C, which was not observed with I2 | |||

| Kelishadi, 2014 [30] | Serum 25OHD: chemiluminescent immunoassay method | I: 45.60 (5.09) C: 44.7 (5.66) (p = 0.48) | I: 79.89 (5.34) C: 47.59 (5.01) (p = 0.02) | I: 134.01 (5.89) C: 136.61 (6.08) (p = 0.53) | I: 131.47 (4.69) C: 135.26 (4.52) (p = 0.07) | NS change in mean arterial pressure in intra-group and inter-group comparisons |

| Mean arterial pressure: ((SBP − DBP)/3) + DBP; with SBP and DBP measured using standard protocol with calibrated instruments (procedure not detailed) | ||||||

| Smith, 2018 [31] | Serum 25OHD: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | I1: 49.2 (12) I2: 51.7 (13.4) C: 46.9 (11.4) | I1: 56.6 (12.4) I2: 63.9 (10.6) C: 30.7 (8.6) (p < 0.001 for all groups, from baseline to endline) | SBP: I1: 124 (13) I2:122 (10) C: 121 (10) | SBP: I1: 123 (11) I2: 121 (8) C: 123 (14) (NS) | NS change in SBP or DBP |

| SBP and DBP: average of 3 readings, 1 min apart, by an automated BP monitor on the non-dominant arm in an upright position with the arm supported | DBP: I1: 69 (10) I2: 67 (7) C: 67 (8) | DBP: I1: 71 (11) I2: 67 (6) C: 68 (10) (NS) |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abboud, M. Vitamin D Supplementation and Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041163

Abboud M. Vitamin D Supplementation and Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041163

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbboud, Myriam. 2020. "Vitamin D Supplementation and Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 12, no. 4: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041163

APA StyleAbboud, M. (2020). Vitamin D Supplementation and Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 12(4), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041163