Scientific Evidence Supporting the Beneficial Effects of Isoflavones on Human Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Oral Intake and Occurrence

3. Bioavailability

4. Biological Activity

4.1. Bone Health Maintenance

4.2. Cardiovascular Risk

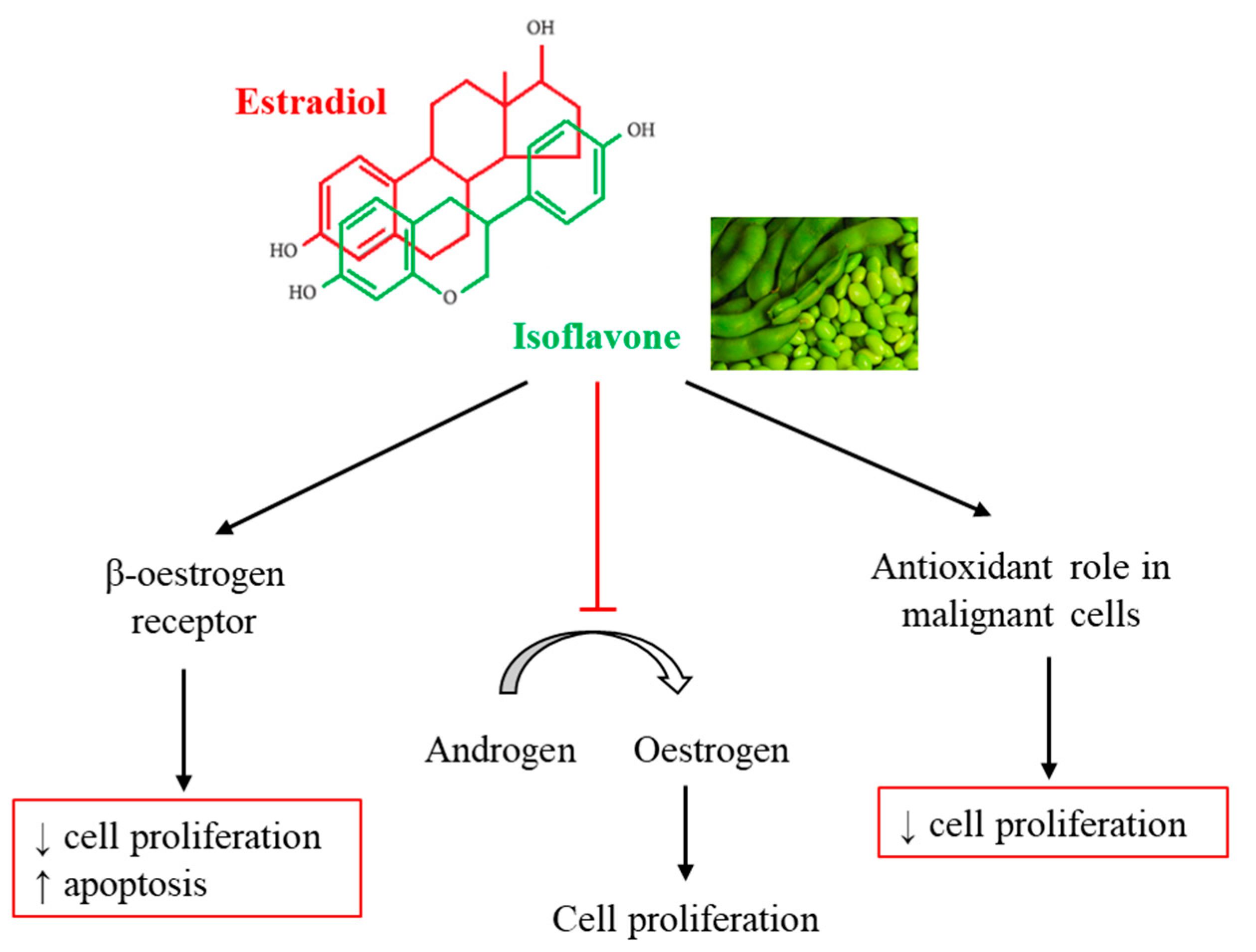

4.3. Cancer

4.4. Menopausal Symptoms

5. Side Effects and Safety

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Biosynthesis of flavonoids and effects of stress. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 2002, 5, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treutter, D. Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance and enhancement of their biosynthesis. Plant Biol. 2005, 7, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirotkin, A.V.; Harrath, A.H. Phytoestrogens and their effects. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 741, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dykens, J.A.; Perez, E.; Liu, R.; Yang, S.; Covey, D.F.; Simpkins, J.W. Neuroprotective effects of 17beta-estradiol and nonfeminizing estrogens against H2O2 toxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endoh, H.; Sasaki, H.; Maruyama, K.; Takeyama, K.; Waga, I.; Shimizu, T.; Kato, S.; Kawashima, H. Rapid activation of MAP kinase by estrogen in the bone cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 235, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Giguère, V. Requirement of Ras-dependent pathways for activation of the transforming growth factor beta3 promoter by estradiol. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoca, A.M.; van den Berg, H.; Vervoort, J.; van der Saag, P.; Ström, A.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Rietjens, I.; Murk, A.J. Influence of cellular ERalpha/ERbeta ratio on the ERalpha-agonist induced proliferation of human T47D breast cancer cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 105, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messina, M.J. Legumes and soybeans: Overview of their nutritional profiles and health effects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 439S–450S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaheer, K.; Humayoun Akhtar, M. An updated review of dietary isoflavones: Nutrition, processing, bioavailability and impacts on human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křížová, L.; Dadáková, K.; Kašparovská, J.; Kašparovský, T. Isoflavones. Molecules 2019, 24, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bustamante-Rangel, M.; Delgado-Zamarreño, M.M.; Perez-Martin, L.; Rodriguez-Gonzalo, E.; Dominguez-Alvarez, J. Analysis of isoflavones in Foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossi, M.; Amaretti, A.; Roncaglia, R.; Leonardi, A.; Raimondi, S. Dietary isoflavones and dietary microbiota: Metabolism and transformation into bioactive compounds. In Isoflavones Biosynthesis, Occurence and Health Effects; Thompson, M.J., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 137–161. [Google Scholar]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Lydeking-Olsen, E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol-a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collison, M.W. Determination of total soy isoflavones in dietary supplements, supplement ingredients, and soy foods by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2008, 91, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kurzer, M.S.; Xu, X. Dietary phytoestrogens. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1997, 17, 353–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saloniemi, H.; Wähälä, K.; Nykänen-Kurki, P.; Kallela, K.; Saastamoinen, I. Phytoestrogen content and estrogenic effect of legume fodder. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1995, 208, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rizzo, G.; Baroni, L. Soy, Soy Foods and Their Role in Vegetarian Diets. Nutrients 2018, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhathena, S.J.; Velasquez, M.T. Beneficial role of dietary phytoestrogens in obesity and diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Database for the Isoflavone Content of Selected Foods, Release 2.0. Available online: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-database-isoflavone-content-selected-foods-release-20 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Messina, M.; Nagata, C.; Wu, A.H. Estimated Asian adult soy protein and isoflavone intakes. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.; Shin, S.; Joung, H. Estimation of dietary flavonoid intake and major food sources of Korean adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Erp-Baart, M.A.; Brants, H.A.; Kiely, M.; Mulligan, A.; Turrini, A.; Sermoneta, C.; Kilkkinen, A.; Valsta, L.M. Isoflavone intake in four different European countries: The VENUS approach. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89 (Suppl. 1), S25–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Schouw, Y.T.; Kreijkamp-Kaspers, S.; Peeters, P.H.; Keinan-Boker, L.; Rimm, E.B.; Grobbee, D.E. Prospective study on usual dietary phytoestrogen intake and cardiovascular disease risk in Western women. Circulation 2005, 111, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsta, L.M.; Kilkkinen, A.; Mazur, W.; Nurmi, T.; Lampi, A.M.; Ovaskainen, M.L.; Korhonen, T.; Adlercreutz, H.; Pietinen, P. Phyto-oestrogen database of foods and average intake in Finland. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89 (Suppl. 1), S31–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lund, S.; Holman, G.D.; Schmitz, O.; Pedersen, O. Contraction stimulates translocation of glucose transporter GLUT4 in skeletal muscle through a mechanism distinct from that of insulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 5817–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, H.H.; Robinson, A.R.; Common, R.H. Excretion of radioactive diadzein and equol as monosulfates and disulfates in the urine of the laying hen. Can. J. Biochem. 1975, 53, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, S.; Wähälä, K.; Adlercreutz, H. Identification of isoflavone metabolites dihydrodaidzein, dihydrogenistein, 6′-OH-O-dma, and cis-4-OH-equol in human urine by gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy using authentic reference compounds. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 274, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S. The biochemistry, chemistry and physiology of the isoflavones in soybeans and their food products. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2010, 8, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, A.J.; Cañada, F.J.; Díaz, J.C.; Kroon, P.A.; Mclauchlan, R.; Faulds, C.B.; Plumb, G.W.; Morgan, M.R.; Williamson, G. Dietary flavonoid and isoflavone glycosides are hydrolysed by the lactase site of lactase phlorizin hydrolase. FEBS Lett. 2000, 468, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheynier, V.; Sarni-Manchado, P.; Quideau, S. (Eds.) Recent Advances in Polyphenol Research; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.M.; DuPont, M.S.; Day, A.J.; Plumb, G.W.; Williamson, G.; Johnson, I.T. Intestinal transport of quercetin glycosides in rats involves both deglycosylation and interaction with the hexose transport pathway. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2765–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, A.; Shiomi, T.; Hachiya, S.; Shigematsu, N.; Hara, H. Low activities of intestinal lactase suppress the early phase absorption of soy isoflavones in Japanese adults. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfakianos, J.; Coward, L.; Kirk, M.; Barnes, S. Intestinal uptake and biliary excretion of the isoflavone genistein in rats. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronis, M.J.; Little, J.M.; Barone, G.W.; Chen, G.; Radominska-Pandya, A.; Badger, T.M. Sulfation of the isoflavones genistein and daidzein in human and rat liver and gastrointestinal tract. J. Med. Food 2006, 9, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoda, K.; Furuta, T.; Yokokawa, A.; Ishii, K. Identification and quantification of daidzein-7-glucuronide-4′-sulfate, genistein-7-glucuronide-4′-sulfate and genistein-4′,7-diglucuronide as major metabolites in human plasma after administration of kinako. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, K.P.; Kim, C.S.; Ahn, Y.; Park, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, J.K.; Lim, Y.K.; Yoo, K.Y.; Kim, S.S. Plasma isoflavone concentration is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes in Korean women but not men: Results from the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaya, P.; Medina, M.; Sánchez-Jiménez, A.; Landete, J.M. Phytoestrogen Metabolism by Adult Human Gut Microbiota. Molecules 2016, 21, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkinson, C.; Frankenfeld, C.L.; Lampe, J.W. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone daidzein: Exploring the relevance to human health. Exp. Biol. Med. 2005, 230, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.; Sanders, K.; Kolybaba, M.; Lopez, D. Case-control study of phyto-oestrogens and breast cancer. Lancet 1997, 350, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterham, T.J.; Shutt, D.A.; Braden, A.W.H.; Tweeddale, H.J. Metabolism of intraruminally administered [4-14C]formononetic and [4-14C]biochanin a in sheep. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1971, 22, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murota, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Uehara, M. Flavonoid metabolism: The interaction of metabolites and gut microbiota. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mace, T.A.; Ware, M.B.; King, S.A.; Loftus, S.; Farren, M.R.; McMichael, E.; Scoville, S.; Geraghty, C.; Young, G.; Carson, W.E.; et al. Soy isoflavones and their metabolites modulate cytokine-induced natural killer cell function. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adlercreutz, H.; Markkanen, H.; Watanabe, S. Plasma concentrations of phyto-oestrogens in Japanese men. Lancet 1993, 342, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.J.; Anderson, K.E. Sex and long-term soy diets affect the metabolism and excretion of soy isoflavones in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 1500S–1504S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelly, G.E.; Nelson, C.; Waring, M.A.; Joannou, G.E.; Reeder, A.Y. Metabolites of dietary (soya) isoflavones in human urine. Clin. Chim. Acta 1993, 223, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Sobue, T.; Takahashi, T.; Miura, T.; Arai, Y.; Mazur, W.; Wähälä, K.; Adlercreutz, H. Pharmacokinetics of soybean isoflavones in plasma, urine and feces of men after ingestion of 60 g baked soybean powder (kinako). J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 1710–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karr, S.C.; Lampe, J.W.; Hutchins, A.M.; Slavin, J.L. Urinary isoflavonoid excretion in humans is dose dependent at low to moderate levels of soy-protein consumption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lambert, M.N.T.; Hu, L.M.; Jeppesen, P.B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of isoflavone formulations against estrogen-deficient bone resorption in peri- and postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akhlaghi, M.; Ghasemi Nasab, M.; Riasatian, M.; Sadeghi, F. Soy isoflavones prevent bone resorption and loss, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2327–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansai, K.; Na Takuathung, M.; Khatsri, R.; Teekachunhatean, S.; Hanprasertpong, N.; Koonrungsesomboon, N. Effects of isoflavone interventions on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, F.; Alimoradi, Z.; Haqi, P.; Mahdizad, F. Effects of phytoestrogens on bone mineral density during the menopause transition: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Climacteric 2016, 19, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, S.; Peroni, G.; Miccono, A.; Riva, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Allegrini, P.; Preda, S.; Baldiraghi, V.; Guido, D.; Rondanelli, M. Multidimensional Effects of Soy Isoflavone by Food or Supplements in Menopause Women: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.R.; Ko, N.Y.; Chen, K.H. Isoflavone Supplements for Menopausal Women: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arjmandi, B.H.; Smith, B.J. Soy isoflavones’ osteoprotective role in postmenopausal women: Mechanism of action. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, R.; Bhalla, Y.; Jain, A.; Chadha, K.; Karan, M. Dietary Soy Isoflavone: A Mechanistic Insight. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.; Je, Y. Flavonoid intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all causes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 20, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Jiao, S.; Dong, W. Association between consumption of soy and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abshirini, M.; Omidian, M.; Kord-Varkaneh, H. Effect of soy protein containing isoflavones on endothelial and vascular function in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 2020, 12, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, B.; Cui, C.; Zhang, X.; Sugiyama, D.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Sekikawa, A. The effect of soy isoflavones on arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalvon-Demersay, T.; Azzout-Marniche, D.; Arfsten, J.; Egli, L.; Gaudichon, C.; Karagounis, L.G.; Tomé, D. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Plant Compared with Animal Protein Sources on Features of Metabolic Syndrome. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rienks, J.; Barbaresko, J.; Nöthlings, U. Association of isoflavone biomarkers with risk of chronic disease and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 616–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachvak, S.M.; Moradi, S.; Anjom-Shoae, J.; Rahmani, J.; Nasiri, M.; Maleki, V.; Sadeghi, O. Soy, Soy Isoflavones, and Protein Intake in Relation to Mortality from All Causes, Cancers, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1483–1500.e1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Gotto, A.M.; Atkin, S.L.; Banach, M.; Pirro, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of soy isoflavone supplementation on plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018, 12, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, C.J.; Tschugguel, W.; Schneeberger, C.; Huber, J.C. Production and actions of estrogens. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Chibber, R.; Ruggiero, D.; Kohner, E.; Ritter, J.; Ferro, A.; Ruggerio, D. Impairment of vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by advanced glycation end products. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vlachopoulos, C.; Aznaouridis, K.; Stefanadis, C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santo, A.S.; Santo, A.M.; Browne, R.W.; Burton, H.; Leddy, J.J.; Horvath, S.M.; Horvath, P.J. Postprandial lipemia detects the effect of soy protein on cardiovascular disease risk compared with the fasting lipid profile. Lipids 2010, 45, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micek, A.; Godos, J.; Brzostek, T.; Gniadek, A.; Favari, C.; Mena, P.; Libra, M.; Del Rio, D.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Dietary phytoestrogens and biomarkers of their intake in relation to cancer survival and recurrence: A comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 79, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Jiang, C. Soy and isoflavones consumption and breast cancer survival and recurrence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 3079–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.T.; Jin, F.; Li, J.G.; Xu, Y.Y.; Dong, H.T.; Liu, Q.; Xing, P.; Zhu, G.L.; Xu, H.; Miao, Z.F. Dietary isoflavones or isoflavone-rich food intake and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.S.; Ge, J.; Chen, S.W.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Ma, S.J.; Chen, Q. Association between Dietary Isoflavones in Soy and Legumes and Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, F.; Gao, J.; Shan, B.; Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y. Oral isoflavone supplementation on endometrial thickness: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 17369–17379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.; Ray, S.; Micek, A.; Pajak, A.; Sciacca, S.; D’Orazio, N.; Del Rio, D.; Galvano, F. A comprehensive meta-analysis on dietary flavonoid and lignan intake and cancer risk: Level of evidence and limitations. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Yu, L.; You, R.; Yang, Y.; Liao, J.; Chen, D. Association among Dietary Flavonoids, Flavonoid Subclasses and Ovarian Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perez-Cornago, A.; Appleby, P.N.; Boeing, H.; Gil, L.; Kyrø, C.; Ricceri, F.; Murphy, N.; Trichopoulou, A.; Tsilidis, K.K.; Khaw, K.T.; et al. Circulating isoflavone and lignan concentrations and prostate cancer risk: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from seven prospective studies including 2,828 cases and 5,593 controls. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applegate, C.C.; Rowles, J.L.; Ranard, K.M.; Jeon, S.; Erdman, J.W. Soy Consumption and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Feng, H.; Qluwakemi, B.; Wang, J.; Yao, S.; Cheng, G.; Xu, H.; Qiu, H.; Zhu, L.; Yuan, M. Phytoestrogens and risk of prostate cancer: An updated meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Sun, L.M. Dietary intake of flavonoid subclasses and risk of colorectal cancer: Evidence from population studies. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 26617–26627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Jing, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D. Soy isoflavone consumption and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Botma, A.; Rudolph, A.; Hüsing, A.; Chang-Claude, J. Phyto-oestrogens and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 2115–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Sun, Y.; Bo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, D.; Cui, H.; Lu, Q. The association between dietary isoflavones intake and gastric cancer risk: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, J.Y.; Qin, L.Q. Soy isoflavones consumption and risk of breast cancer incidence or recurrence: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 125, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ros, R.; Knaze, V.; Rothwell, J.A.; Hémon, B.; Moskal, A.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A.; Kyrø, C.; Fagherazzi, G.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; et al. Dietary polyphenol intake in Europe: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1359–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, A.; Boulle, N.; Lazennec, G.; Vignon, F.; Pujol, P. Loss of ERbeta expression as a common step in estrogen-dependent tumor progression. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2004, 11, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daily, J.W.; Ko, B.S.; Ryuk, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Park, S. Equol Decreases Hot Flashes in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Med. Food 2019, 22, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.N.; Lin, C.C.; Liu, C.F. Efficacy of phytoestrogens for menopausal symptoms: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Climacteric 2015, 18, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Xu, L.; Zheng, Q. Quantitative efficacy of soy isoflavones on menopausal hot flashes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, J.; Dong, L.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, Q. Comparative efficacy of nonhormonal drugs on menopausal hot flashes. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, G.; Pedder, H.; Dias, S.; Guo, Y.; Lumsden, M.A. Vasomotor symptoms resulting from natural menopause: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of treatment effects from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on menopause. BJOG 2017, 124, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, O.H.; Chowdhury, R.; Troup, J.; Voortman, T.; Kunutsor, S.; Kavousi, M.; Oliver-Williams, C.; Muka, T. Use of Plant-Based Therapies and Menopausal Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 315, 2554–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hairi, H.A.; Shuid, A.N.; Ibrahim, N.; Jamal, J.A.; Mohamed, N.; Mohamed, I.N. The Effects and Action Mechanisms of Phytoestrogens on Vasomotor Symptoms During Menopausal Transition: Thermoregulatory Mechanism. Curr. Drug Targets 2019, 20, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, P.J. Is equol production beneficial to health? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2011, 70, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EFSA Pannel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources Added to Food (ANS). Risk assessment for peri- and post-menopausal women taking food su pplements containing isola ted isoflavones. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffy, C.; Perez, K.; Partridge, A. Implications of phytoestrogen intake for breast cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2007, 57, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Arjomand-Wölkart, K.; Birkhäuser, M.H.; Genazzani, A.R.; Gruber, D.M.; Huber, J.; Kölbl, H.; Kreft, S.; Leodolter, S.; Linsberger, D.; et al. Consensus: Soy isoflavones as a first-line approach to the treatment of menopausal vasomotor complaints. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2016, 32, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulka, R.A.; Matsuura, I.; Uesugi, T.; Ueno, T.; Burdock, G. Developmental and Reproductive Effects of SE5-OH: An Equol-Rich Soy-Based Ingredient. J. Toxicol. 2009, 2009, 307618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isoflavone Content and Chemical Forms in Soybeans | |

|---|---|

| Aglycones | Daidzein, genistein, glycitein |

| Glycosides | Daidzin, genistin, glycitin |

| Acetylglycosides | Acetyldaidzin, acetylgenistin, acetylglycitin |

| Malonylglycosides | Malonyldaidzin, malonylgenistin, malonylglycitin |

| Authors | Number of Studies Included | Type of Studies Included | Number of Participants and Gender/Age/Characteristics | Compound and Doses | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | |||||

| Lambert et al., 2017 [48] | 26 | Randomized Clinical trials | 2652 estrogen-deficient women | Isoflavones (different forms) Intervention period: ≥3 months | Moderate attenuation of bone loss, primarily at the level of the lumbar spine and the femoral neck |

| Akhlaghi et al., 2019 [49] | 52 | Controlled trials | 5313 patients | Soy isoflavones 40–300 mg/day Intervention period: 1 month–3 years | Prevention of osteoporosis-related bone loss in any weight status or treatment duration |

| Sansai et al., 2020 [50] | 63 | Controlled trials | 6427 postmenopausal women | Isoflavones (different forms) Intervention period: 1–36 months | Isoflavone interventions, genistein (54 mg/day) and ipriflavone (600 mg/day) in particular hold great promise in the prevention and treatment of bone mineral density |

| Systematic reviews | |||||

| Abdi et al., 2016 [51] | 23 | Clinical trials | 3494 participants | Isoflavones Intervention duration: 7 weeks–3 years | Probably they have beneficial effects on bone health in menopausal women but there are controversial reports about changes in bone mineral density |

| Perna et al., 2016 [52] | 9 | Clinical trials | 1379 menopausal and postmenopausal women | Soy isoflavones (20–80 mg) and equol (10 mg) | May be protective in osteoporosis |

| Chen et al., 2019 [53] | 3 | 1Meta-analysis 1Systematic review and 1clinical trial | 3663 menopausal and postmenopausal women | Soy isoflavones | Attenuation of lumbar spine bone mineral density |

| Authors | Number of Studies Included | Type of Studies Included | Number of Participants and Gender/Age/Characteristics | Compound and Doses | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | |||||

| Kim and Je, 2017 [56] | 13 | Prospective studies | 338,541 participants Age ranging from 40–84 years Follow-up period from 4 to 28 years | Intake data not provided | No association with mortality from CVD |

| Yan et al., 2017 [57] | 17 | Prospective cohort and case-control studies | 508,841 participants, 17,269 with CVD events (stroke, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke) Follow-up period from 6.3 to 16 years | Isoflavones 0.025–53.6 mg/day | No associations between soy isoflavones consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and coronary heart disease |

| Abshirini et al., 2020 [58] | 5 | Randomized clinical trials | 548 participants (272 case and 276 controls) Age not available | Isoflavones 49.3–118 mg/day Intervention period: 1–12 months | Non-significant change in flow-mediated dilation (parameter of endothelial function) |

| Man et al., 2020 [59] | 8 | Various designs (double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel design, crossover design) | 485 participants (276 women and 209 men) Age ranging from 35–75 years | Isoflavones 80–118 mg/day and 10 mg/day of S-equol Intervention period: 1 day–12 weeks | Positive effect of soy isoflavones on arterial stiffness |

| Systematic reviews | |||||

| Perna et al., 2016 [52] | 12 | Randomized clinical trials | 139–1268 menopausal and postmenopausal women | Isoflavones 20 to 100 mg/day Intervention period: 8 weeks–2 years | Reduction in total cholesterol and triglyceride plasma concentrations Reduction in nitric oxide and malonaldehyde |

| Chalvon-Demersay et al., 2017 [60] | 17 3 | Randomized clinical trials; nutritional intervention | 337 healthy, diabetic or hypercholesterolemic individuals Age: 18–74 years 406 healthy, postmenopausal or obese participants Age: 50–79 years | Isoflavones 3 to 102 mg/day Intervention period: 4–208 weeks Isoflavones 60 to 135 mg/day Intervention period: 3–12 months | Reduction in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol Changes in systolic or diastolic blood pressure (increase and decrease, depending on the study) |

| Rienks et al., 2017 [61] | 3 | Prospective studies | 68,748 individuals Age: 40–70 years | Follow-up period: up to 10 years | Decreased risk of acute coronary syndrome or coronary heart disease No association with ischemic stroke |

| Authors | Number of Studies Included (Meta-Analysis) | Type of Studies Included | Number of Participants and Gender/Age Characteristics | Compound and Doses | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nachvack et al., 2019 [62] | 23 | Prospective study | 330,826 (12 studies in both genders and 11 in women) | Soy/soy products (10 mg/day) | Inverse association with cancer deaths. 7% lower risk of gastric, colorectal, and lung cancer mortality |

| Breast cancer | |||||

| Nachvack et al., 2019 [62] | 23 | Prospective study | 330,826 (12 studies in both genders and 11 in women) | Soy/soy products (10 mg/day) | 9% lower risk of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer mortality |

| Micek et al., 2020 [68] | 15 | Cohort study | 49,659 | Isoflavone intake (0.0036–62.7 mg/day) | Inverse association between isoflavone intake and both overall mortality and breast cancer recurrence |

| Qiu et al., 2018 [69] | 12 | Prospective cohort study | 37,275 women | Isoflavones (the amount varies greatly among different soy foods) | Pre-diagnosis, soy isoflavone consumption has a poor effect on survival of postmenopausal women |

| Zhao et al., 2019 [70] | 16 | Prospective cohort study | 648,913 (11,169 breast cancer cases) | High dietary intake of soy foods (dose non-defined) | Significant reduction of breast cancer risk |

| Rienks et al., 2017 [61] | 10 | Case-control study | Sample sizes (from 100 to 15,688 participants) | Daidzein, genistein, and equol (dose non-defined) | Daidzein (34%) and genistein (28%) were associated with a lower risk of breast cancer |

| Endometrial cancer | |||||

| Zhong et al., 2016 [71] | 13 | Prospective cohort study (3) Case-control study (10) | 178,947 (7067 cases and 171,880 controls) | Soy products (0.05–130 g/day) and total isoflavones (0.28 to 63 mg/day). | 19% reduction in endometrial cancer risk. Higher reduction in Asian women |

| Liu et al., 2016 [72] | 23 | Randomized controlled trials | 2167 | More than 54 mg isoflavone/day | Reduction of the endometrial thickness in North American women (for 0.23 mm). Opposite effect in Asian women |

| Grosso et al., 2017 [73] | 8 | Prospective studies (3) Case-control studies (5) | Non-defined | Isoflavone consumption (>45 mg/day among the Asian population, and >1 mg/day among the non-Asian population) | Potential reduction risk associated with isoflavone consumption |

| Ovarian cancer | |||||

| Hua et al., 2016 [74] | 12 | Prospective cohort study (5) Case-control study (7) | 6275 cases and 393,776 controls | Isoflavone intake (0.01–41 mg/day) | 33% reduction in ovarian cancer risk |

| Prostate cancer | |||||

| Pérez-Cornago et al., 2018 [75] | 7 | Cohort prospective study (2 studies from Japan and 5 studies from Europe) | 241 cases and 503 controls (from Japanese studies), and 2828 cases and 5593 controls (from European studies) 60–69 years-old | Circulating isoflavone concentrations (nmol/L): Daidzein (Japanese: 115–166; European: 2.84–3.96) Genistein (Japanese: 277–454; European: 4.84–5.97), and equol (Japanese: 10.3–24; European: 0.25–0.65) | Genistein, daidzein and equol did not affect prostate cancer risk in both Japanese and European men |

| Applegate et al., 2018 [76] | 30 | Case-control study (15) Cohort study (8) Nested case-control study (7) | 266,699 (21,612 patients with prostate cancer) | Soy foods (<90 mg/day) | Isoflavones were not associated with a reduction of prostate cancer risk Metabolites (genistein and daidzein) consumption was associated with a reduction of prostate cancer risk |

| Rienks et al., 2017 [61] | 8 | Case-control study | Sample sizes (10–15,688 participants) | Daidzein, genistein, and equol (dose not defined) | 19% reduction in prostate cancer risk was found at high concentrations of daidzein, but not with genistein or equol |

| Zhang et al., 2017 [77] | 23 | Case-control study (21) Cohort study (2) | Participants: 11,346 cases and 140,177 controls | Daidzein, genistein, and equol (dose not defined) | Daidzein and genistein intakes were associated with a reduction of prostate cancer risk (no effect with equol) |

| Colorectal cancer | |||||

| He et al., 2016 [78] | 18 | Case-control study (9) Cohort study (9) | 559,486 (among them 16,917 colorectal cancer cases) | Foods rich in isoflavones (dose not defined) | Reduction of colorectal cancer risk. This association is stronger among postmenopausal women than premenopausal women |

| Yu et al., 2016 [79] | 17 | Case-control study (13) Prospective cohort study (4) | 272,296 participants | Soy foods (30 mg/day–170 g/day) and isoflavones (0.014–60 mg/day) | 23% reduction in colorectal cancer risk. Potential protective effect in the Asian population (their consumption is higher than in the Western population) |

| Jiang et al., 2016 [80] | 17 | Case-control study (9) Cohort study (8) | 317,599 participants | Isoflavones (0.025–74 mg/day). | Inverse association between isoflavone consumption and colorectal cancer risk in case-control studies, but not in cohort studies. 8% reduction in colorectal neoplasm risk for every 20 mg/day increase in isoflavone intake (Asian population) and for every 0.1 mg/day increase (Western population) |

| Gastric cancer | |||||

| You et al., 2018 [81] | 12 | Cohort study (6) Case-control study (6) | 596,553 participants | Isoflavones (high dose: 0.6–75.5 mg/day; and low dose: 0.01–20.1 mg/day). | No association between isoflavone consumption and gastric cancer risk with the highest versus the lowest categories of dietary isoflavone intake |

| Authors | Number of Studies Included | Type of Studies Included | Number of Participants and Gender/Age/Characteristics | Compound and Doses | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | |||||

| Chen et al., 2015 [86] | 15 | RCT | 30–252 perimenopausal or postmenopausal women/report (1753 in total) 49–58.3 years (placebo group) 48–60.1 years (phytoestrogen group) | Isoflavones 5–100 mg/day Intervention period: 3–12 months | Reduction of hot flush frequency (vs. placebo) |

| Li et al., 2015 [87] | 16 | RCT | 24–236 women/report (median 90) 40–65 years | Soy isoflavones 30–200 mg/day Intervention period: 4 weeks–2 years (median 12 weeks) | Slight and slow attenuation of hot flushes (vs. estradiol) |

| Li et al., 2016 [88] | 39 | RCT | 24–620 women/report (median 200) Age not available | SSRIs/SNRIs: 7.5–200 mg/day Gabapentin: 300–1800 mg/day Clonidine: 0.1–0.4 mg/day Soy isoflavones: 30–200 mg/day Intervention period: 2–96 weeks (average 12 weeks) | Slight and slow attenuation of hot flushes (vs. non-hormonal drugs) |

| Daily et al., 2019 [85] | 5 | RCT | 728 menopausal women (total subjects) 50.5–58.8 years (mean) | Soy isoflavones: 33–200 mg/day and 6 g soy extract/day Equol: 10 mg/day Intervention period: not available | Equol or isoflavone in equol-producers more effective than placebo |

| Sarri et al., 2017 [89] | 32 | RCT | 4165 menopausal women (total subjects) 45+ years | Isoflavones and black cohosh (Doses not available) | Reduction of VSM (hot flushes and night sweats) compared to placebo No beneficial effect (vs. pharmacological treatment) |

| Franco et al., 2016 [90] | 17 | RCT | 30–252 women/trial 40–69 years | Dietary soy isoflavones: 42–90 mg/day Supplements and extracts of soy isoflavones: 10–100 mg/day Red clover: 40–160 mg/day Intervention period: 12–48 weeks | Reduction of hot flush frequency by means of dietary isoflavones and supplements) Reduction of night sweat frequency by red clover |

| Systematic reviews | |||||

| Chen et al., 2019 [86] | 15 | RCT (9) Prospective study (2) Systematic review (2) Randomized crossover trial (1) Meta-analysis (2) | 51–403 menopausal and postmenopausal women | Soy (soy nut, soy protein, soy extracts) Natural isoflavones Synthetic isoflavones | Beneficial effects of isoflavones (vs. placebo) Synthetic or combination of isoflavones more effective than natural soy HRT more effective than soy or its extracts Isoflavone in equol-producers or equol supplementation more effective than placebo. |

| Perna et al., 2016 [52] | 7 | RCT | 40–403 menopausal and postmenopausal women | Isoflavones 50–120 mg/day Intervention period: 8 weeks–2 years | Reduction of hot flush frequency |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez-Zorita, S.; González-Arceo, M.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Eseberri, I.; Trepiana, J.; Portillo, M.P. Scientific Evidence Supporting the Beneficial Effects of Isoflavones on Human Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123853

Gómez-Zorita S, González-Arceo M, Fernández-Quintela A, Eseberri I, Trepiana J, Portillo MP. Scientific Evidence Supporting the Beneficial Effects of Isoflavones on Human Health. Nutrients. 2020; 12(12):3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123853

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-Zorita, Saioa, Maitane González-Arceo, Alfredo Fernández-Quintela, Itziar Eseberri, Jenifer Trepiana, and María Puy Portillo. 2020. "Scientific Evidence Supporting the Beneficial Effects of Isoflavones on Human Health" Nutrients 12, no. 12: 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123853

APA StyleGómez-Zorita, S., González-Arceo, M., Fernández-Quintela, A., Eseberri, I., Trepiana, J., & Portillo, M. P. (2020). Scientific Evidence Supporting the Beneficial Effects of Isoflavones on Human Health. Nutrients, 12(12), 3853. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123853