Consumers’ Responses to Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Results from a Sample from The Netherlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population Study and Individual Characteristics

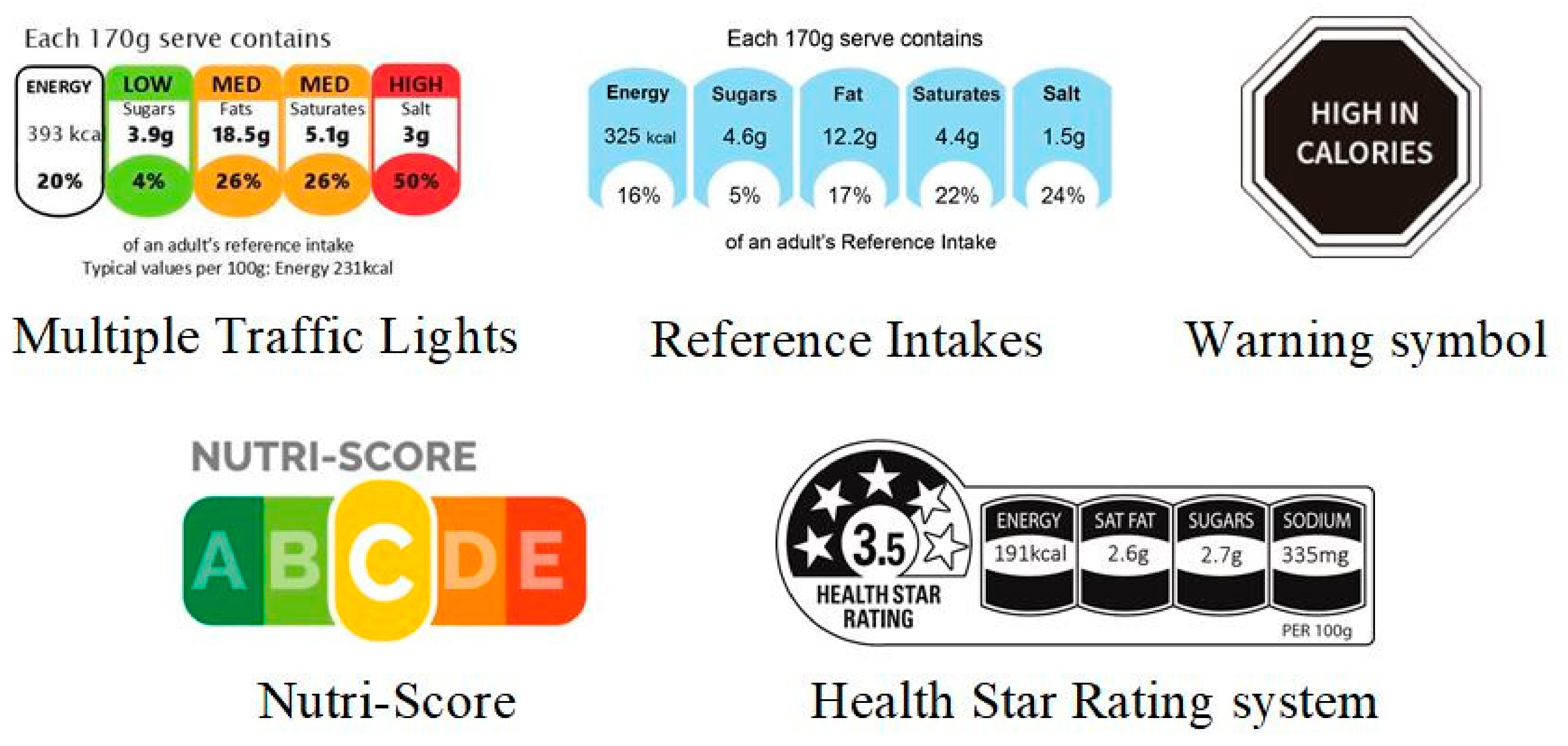

2.2. Stimuli and Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels

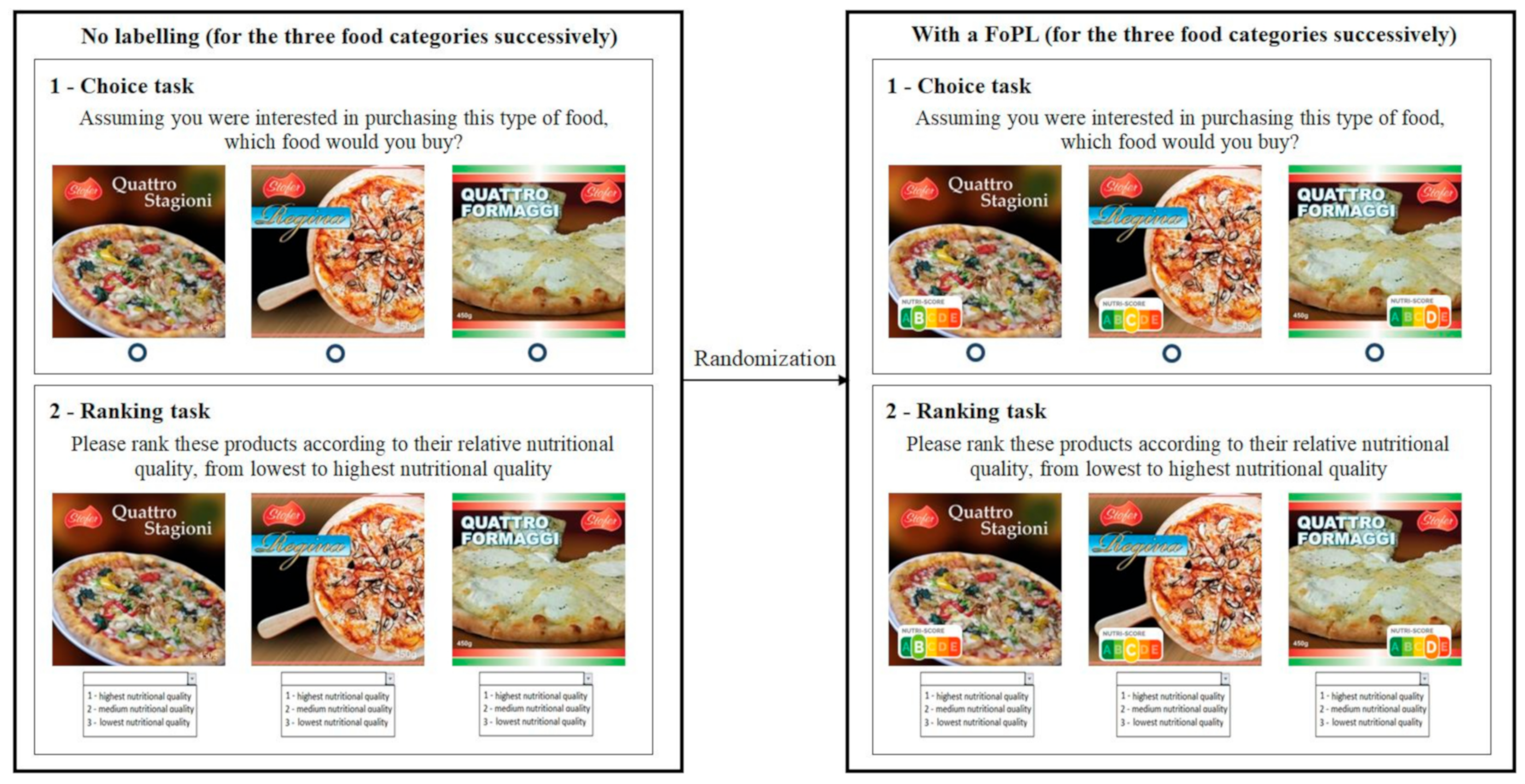

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Food Choice

2.4.2. Objective Understanding

2.4.3. Perception

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

3.2. Food Choices

3.3. Objective Understanding

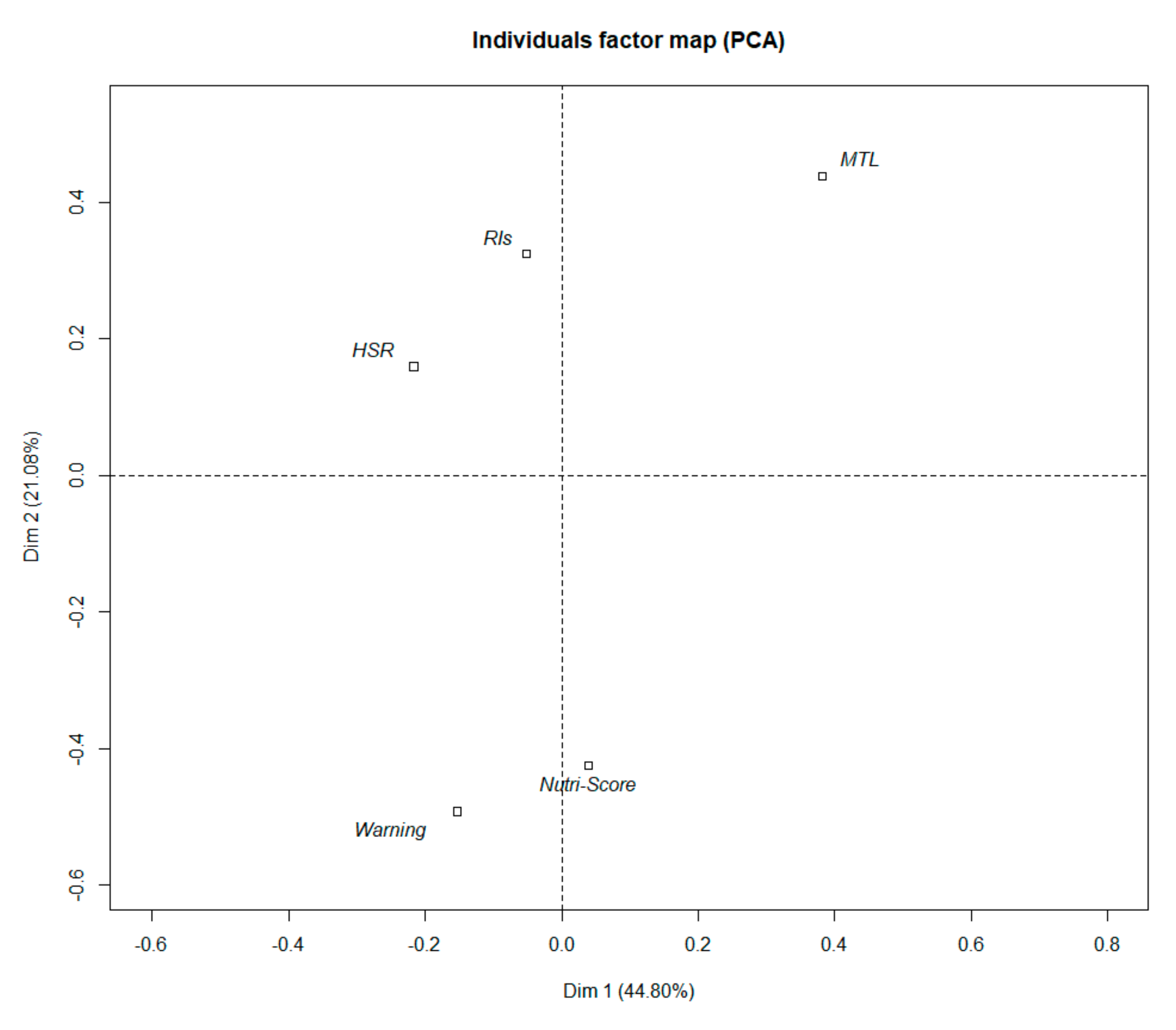

3.4. Perception

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Promoting Sustainable Consumption—Good Practices in OECD Countries; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kleef, E.V.; Dagevos, H. The growing role of front-of-pack nutrition profile labeling: A consumer perspective on key issues and controversies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyth, E.L.; Steenhuis, I.H.; Roodenburg, A.J.; Brug, J.; Seidell, J.C. Front-of-pack nutrition label stimulates healthier product development: A quantitative analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Eyles, H.; Choi, Y.-H. Effects of a Voluntary Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling System on Packaged Food Reformulation: The Health Star Rating System in New Zealand. Nutrients 2017, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. NCDs Tackling NCDs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: http://www.who.int/ncds/management/best-buys/en/ (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Scrinis, G.; Parker, C. Front-of-Pack Food Labeling and the Politics of Nutritional Nudges. Law Policy 2016, 38, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A.K.; Adamson, A.J.; Clegg, S.; Malam, S.; Rigg, M.; Duncan, S. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: Are multiple formats a problem for consumers? Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Europa Summary of EU legislation. Labeling of Foodstuffs. Regulation (EU) No. 1169/2011; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goiana-da-Silva, F.; Cruz-E-Silva, D.; Miraldo, M.; Calhau, C.; Bento, A.; Cruz, D.; Almeida, F.; Darzi, A.; Araújo, F. Front-of-pack labelling policies and the need for guidance. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thow, A.M.; Jones, A.; Schneider, C.H.; Labonté, R. Global Governance of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: A Qualitative Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asp, N.-G. Bryngelsson Susanne Health claims in the labelling and marketing of food products: The Swedish food sector’s Code of Practice in a European perspective. Scand. J. Food Nutr. 2007, 15, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standard Agency. Front-of-Pack Traffic Light Signpost Labelling Technical Guidance; Food Standard Agency: Kingsway, UK, 2007; pp. 2–12.

- Food and Drink Federation. Reference Intakes (Previously Guideline Daily Amounts); Food and Drink Federation: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arrêté du 31 Octobre 2017 Fixant la Forme de Présentation Complémentaire à la Déclaration Nutritionnelle Recommandée par l’Etat en Application des Articles L. 3232-8 et R. 3232-7 du Code de la Santé Publique|Legifrance. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/arrete/2017/10/31/SSAP1730474A/jo/texte (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- ENL Taskforce. Promoting Healthier Diets Through Evolved Nutrition Labelling. ENL Taskforce, 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/ev_20171130_co03_en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Choices International Foundation Dutch Choices Logo Gets One Year Extra. Available online: https://www.choicesprogramme.org/news-updates/news/dutch-choices-logo-gets-one-year-extra (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Niamh Michail Dutch Government Mulls Nutrition Logo. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2018/04/18/Dutch-government-mulls-nutrition-logo (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Grunert, K.G.; Wills, J.M. A review of European research on consumer response to nutrition information on food labels. J. Public Health 2007, 15, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejean, C.; Macouillard, P.; Peneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Castetbon, K. Consumer acceptability and understanding of front-of-pack nutrition labels. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, C.; Peneau, S.; Buscail, C.; Gonzalez, R.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Perception of different formats of front-of-pack nutrition labels according to sociodemographic, lifestyle and dietary factors in a French population: Cross-sectional study among the NutriNet-Sante cohort participants. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrot, P.; Mejean, C.; Julia, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.; Hercberg, S.; Peneau, S. Effectiveness of Front-Of-Pack Nutrition Labels in French Adults: Results from the NutriNet-Sante Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Kelly, B.; Ball, K.; Dixon, H.; Shilton, T. Consumers’ responses to front-of-pack labels that vary by interpretive content. Appetite 2016, 101, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Grunert, K.G.; van Trijp, H.C.; Bialkova, S.; Raats, M.M.; Hodgkins, C.; Wasowicz-Kirylo, G.; Koenigstorfer, J. Effects of nutrition label format and product assortment on the healthfulness of food choice. Appetite 2013, 71, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcombe, K.; Fraser, I.; Falco, S.D. Traffic lights and food choice: A choice experiment examining the relationship between nutritional food labels and price. Food Policy 2010, 35, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgmeier, I.; Westenhoefer, J. Impact of different food label formats on healthiness evaluation and food choice of consumers: A randomized-controlled study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrad, A.M.; Louie, J.C.-Y.; Milosavljevic, M.; Kelly, B.; Flood, V.M. Consumer support for healthy food and drink vending machines in public places. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchini, M.; Warin, L. Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoph, M.J.; Ellison, B. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Relationship between Nutrition Label Use and Food Selection, Servings, and Consumption in a University Dining Setting. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducrot, P.; Julia, C.; Mejean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.K.; Hercberg, S.; Peneau, S. Impact of Different Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels on Consumer Purchasing Intentions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski Findling, M.T.; Werth, P.M.; Musicus, A.A.; Bragg, M.A.; Graham, D.J.; Elbel, B.; Roberto, C.A. Comparing five front-of-pack nutrition labels’ influence on consumers’ perceptions and purchase intentions. Prev. Med. 2018, 106, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julia, C.; Blanchet, O.; Mejean, C.; Peneau, S.; Ducrot, P.; Alles, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Touvier, M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Singler, E.; et al. Impact of the front-of-pack 5-colour nutrition label (5-CNL) on the nutritional quality of purchases: An experimental study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maubach, N.; Hoek, J.; Mather, D. Interpretive front-of-pack nutrition labels. Comparing competing recommendations. Appetite 2014, 82, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Volkova, E.; Jiang, Y.; Eyles, H.; Michie, J.; Neal, B.; Blakely, T.; Swinburn, B.; Rayner, M. Effects of interpretive nutrition labels on consumer food purchases: The Starlight randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talati, Z.; Norman, R.; Pettigrew, S.; Neal, B.; Kelly, B.; Dixon, H.; Ball, K.; Miller, C.; Shilton, T. The impact of interpretive and reductive front-of-pack labels on food choice and willingness to pay. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterlander, W.E.; Steenhuis, I.H.M.; de Boer, M.R.; Schuit, A.J.; Seidell, J.C. Effects of different discount levels on healthy products coupled with a healthy choice label, special offer label or both: Results from a web-based supermarket experiment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Crosetto, P.; D’Almeida, T.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Ruffieux, B.; Hercberg, S.; Muller, L.; Julia, C. Modelling the impact of different front-of-package nutrition labels on mortality from non-communicable chronic disease. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Objective Understanding of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels: An International Comparative Experimental Study across 12 Countries. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C. Comparison of front-of-pack labels to help German consumers understand the nutritional quality of food products. Ernährungs Umsch. 2019, 66, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Galan, P.; Egnell, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Babio, N.; Pettigrew, S.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C. Understanding of different front-of-package labels by the Spanish population: Results of a comparative study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejean, C.; Macouillard, P.; Peneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Castetbon, K. Perception of front-of-pack labels according to social characteristics, nutritional knowledge and food purchasing habits. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrúa, A.; Machín, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Martínez, J.; Antúnez, L.; Alcaire, F.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Warnings as a directive front-of-pack nutrition labelling scheme: Comparison with the Guideline Daily Amount and traffic-light systems. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2308–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feunekes, G.I.; Gortemaker, I.A.; Willems, A.A.; Lion, R.; van den Kommer, M. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: Testing effectiveness of different nutrition labelling formats front-of-pack in four European countries. Appetite 2008, 50, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Ball, K.; Hughes, C.; Kelly, B.; Neal, B.; Dixon, H. The relative ability of different front-of-pack labels to assist consumers discriminate between healthy, moderately healthy, and unhealthy foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Hughes, C.; Chapman, K.; Louie, J.C.; Dixon, H.; Crawford, J.; King, L.; Daube, M.; Slevin, T. Consumer testing of the acceptability and effectiveness of front-of-pack food labelling systems for the Australian grocery market. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herpen, E.; Hieke, S.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Inferring Product Healthfulness from Nutrition Labelling: The Influence of Reference Points. Appetite 2013, 72, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, P.; Muller, L.; Ruffieux, B. Réponses des consommateurs à trois systèmes d’étiquetage nutritionnels en face avant. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 2016, 59, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, P.; Lacroix, A.; Muller, L.; Ruffieux, B. Modification des achats alimentaires en réponse à cinq logos nutritionnels. Cah. Nutr. Diététique 2017, 52, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tórtora, G.; Machín, L.; Ares, G. Influence of nutritional warnings and other label features on consumers’ choice: Results from an eye-tracking study. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.B.; Jones, A.C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Roberto, C.A.; Hammond, D. Taxes and front-of-package labels improve the healthiness of beverage and snack purchases: A randomized experimental marketplace. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, P.; Wolfenden, L.; Chapman, K.; Wellard, L.; Hughes, C.; Wiggers, J. The effect of energy and traffic light labelling on parent and child fast food selection: A randomised controlled trial. Appetite 2014, 73, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamlin, R.; McNeill, L. Does the Australasian “Health Star Rating” Front of Pack Nutritional Label System Work? Nutrients 2016, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, G.; Rayner, M.; Swinburn, B. Impact of front-of-pack “traffic-light” nutrition labelling on consumer food purchases in the UK. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, G.; Tikellis, K.; Millar, L.; Swinburn, B. Impact of “traffic-light” nutrition information on online food purchases in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2011, 35, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seward, M.W.; Block, J.P.; Chatterjee, A. A Traffic-Light Label Intervention and Dietary Choices in College Cafeterias. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1808–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamlin, R.P.; McNeill, L.S.; Moore, V. The impact of front-of-pack nutrition labels on consumer product evaluation and choice: An experimental study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Riis, J.; Sonnenberg, L.M.; Levy, D.E. Traffic-light labels and choice architecture: Promoting healthy food choices. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antúnez, L.; Giménez, A.; Maiche, A.; Ares, G. Influence of Interpretation Aids on Attentional Capture, Visual Processing, and Understanding of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 292–299.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, O.; Mills, B.; Phan, T. An independent assessment of the Australian food industry’s Daily Intake Guide “Energy Alone” label. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2011, 22, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducrot, P.; Mejean, C.; Julia, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.K.; Hercberg, S.; Peneau, S. Objective Understanding of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels among Nutritionally At-Risk Individuals. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7106–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, J.C.; Wohlgenant, K.C.; Arsenault, J.E.; Kosa, K.M.; Muth, M.K. Effects of front-of-package and shelf nutrition labeling systems on consumers. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiljevic, M.; Pechey, R.; Marteau, T.M. Making food labels social: The impact of colour of nutritional labels and injunctive norms on perceptions and choice of snack foods. Appetite 2015, 91, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; Juhl, H.J.; Wasowicz-Kirylo, G.; Stysko-Kunkowska, M.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Attention mediates the effect of nutrition label information on consumers’ choice. Evidence from a choice experiment involving eye-tracking. Appetite 2014, 76, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagle, M.G.; Osorio, D. The tuning of human photopigments may minimize red-green chromatic signals in natural conditions. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1993, 252, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Egnell, M.; Ducrot, P.; Touvier, M.; Allès, B.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Julia, C. Objective understanding of Nutri-Score Front-Of-Package nutrition label according to individual characteristics of subjects: Comparisons with other format labels. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 517 | 50.1 |

| Women | 515 | 49.9 |

| Age, years | ||

| 18–30 | 345 | 33.43 |

| 31–50 | 343 | 33.24 |

| ≥ 51 | 344 | 33.33 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary education | 13 | 1.26 |

| Secondary education | 314 | 30.43 |

| Trade certificate | 277 | 26.84 |

| University, undergraduate degree | 329 | 31.88 |

| University postgraduate degree | 99 | 9.59 |

| Level of household monthly income | ||

| High | 342 | 33.14 |

| Medium | 343 | 33.24 |

| Low | 347 | 33.62 |

| Responsible for grocery shopping | ||

| Yes | 746 | 72.29 |

| No | 55 | 5.33 |

| Share job equally | 231 | 22.38 |

| Self-estimated diet quality | ||

| I eat a very unhealthy diet | 8 | 0.78 |

| I eat a mostly unhealthy diet | 102 | 9.88 |

| I eat a mostly healthy diet | 865 | 83.82 |

| I eat a very healthy diet | 57 | 5.52 |

| Nutrition knowledge | ||

| I do not know anything about nutrition | 7 | 0.68 |

| I am not very knowledgeable about nutrition | 157 | 15.21 |

| I am somewhat knowledgeable about nutrition | 744 | 72.09 |

| I am very knowledgeable about nutrition | 124 | 12.02 |

| Did you see the FOP label during the survey? | ||

| No | 293 | 28.39 |

| Unsure | 133 | 12.89 |

| Yes | 606 | 58.72 |

| Participants who recalled seeing the FoPL they were exposed to | ||

| HSR | 111 | 53.62 |

| MTL | 135 | 65.53 |

| Nutri-Score | 147 | 71.36 |

| RIs label | 136 | 53.88 |

| Warning symbol | 77 | 37.20 |

| Food Category | N | HSR | MTL | Nutri-Score | Warning Symbol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| All categories | 898 | 1.21 [0.76–1.94] | 0.4 | 0.94 [0.59–1.51] | 0.8 | 1.10 [0.69–1.75] | 0.7 | 1.32 [0.82–2.13] | 0.3 |

| Pizzas | 692 | 1.11 [0.58–2.10] | 0.8 | 0.85 [0.45–1.64] | 0.6 | 0.76 [0.40–1.44] | 0.4 | 0.88 [0.45–1.73] | 0.7 |

| Cakes | 744 | 0.81 [0.44–1.49] | 0.5 | 0.90 [0.50–1.63] | 0.7 | 1.10 [0.61–1.98] | 0.7 | 0.93 [0.50–1.71] | 0.8 |

| Breakfast cereals | 643 | 1.72 [0.84–3.50] | 0.1 | 0.93 [0.46–1.88] | 0.8 | 1.77 [0.87–3.60] | 0.1 | 2.99 [1.45–6.21] | 0.003 |

| Food Category | N | HSR | MTL | Nutri-Score | Warning Symbol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| All categories | 1032 | 1.20 [0.82–1.75] | 0.3 | 1.31 [0.90–1.90] | 0.2 | 3.60 [2.48–5.24] | <0.0001 | 1.23 [0.84–1.81] | 0.3 |

| Pizzas | 972 | 1.37 [0.85–2.21] | 0.2 | 1.17 [0.73–1.88] | 0.5 | 2.12 [1.34–3.37] | 0.001 | 1.00 [0.62–1.62] | 1.0 |

| Cakes | 1019 | 1.42 [0.89–2.24] | 0.1 | 1.66 [1.05–2.62] | 0.03 | 4.52 [2.89–7.06] | <0.0001 | 2.10 [1.32–3.34] | 0.002 |

| Breakfast cereals | 931 | 0.90 [0.56–1.47] | 0.7 | 1.00 [0.62–1.62] | 1.0 | 2.66 [1.68–4.21] | <0.0001 | 0.85 [0.52–1.39] | 0.5 |

| Questions | Contributions | Coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | |

| This label is confusing | 19.59 | 12.88 | −1.65 | 0.92 |

| I like this label | 10.40 | 18.14 | 1.20 | 1.09 |

| This label does not stand out | 7.09 | 20.36 | −0.99 | 1.15 |

| This label is easy to understand | 18.51 | 2.03 | 1.61 | 0.36 |

| This label takes too long to understand | 15.06 | 22.64 | −1.45 | 1.22 |

| This label provides me the information I need | 16.58 | 13.28 | 1.52 | 0.93 |

| I trust this label | 12.76 | 10.66 | 1.33 | 0.84 |

| HSR | - | - | −0.22 | 0.16 |

| MTL | - | - | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| Nutri-Score | - | - | 0.04 | −0.43 |

| RIs label | - | - | −0.05 | 0.32 |

| Warning symbol | - | - | −0.15 | −0.49 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Gombaud, M.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Consumers’ Responses to Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Results from a Sample from The Netherlands. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081817

Egnell M, Talati Z, Gombaud M, Galan P, Hercberg S, Pettigrew S, Julia C. Consumers’ Responses to Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Results from a Sample from The Netherlands. Nutrients. 2019; 11(8):1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081817

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgnell, Manon, Zenobia Talati, Marion Gombaud, Pilar Galan, Serge Hercberg, Simone Pettigrew, and Chantal Julia. 2019. "Consumers’ Responses to Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Results from a Sample from The Netherlands" Nutrients 11, no. 8: 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081817

APA StyleEgnell, M., Talati, Z., Gombaud, M., Galan, P., Hercberg, S., Pettigrew, S., & Julia, C. (2019). Consumers’ Responses to Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Results from a Sample from The Netherlands. Nutrients, 11(8), 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081817