Genes and Dietary Fatty Acids in Regulation of Fatty Acid Composition of Plasma and Erythrocyte Membranes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

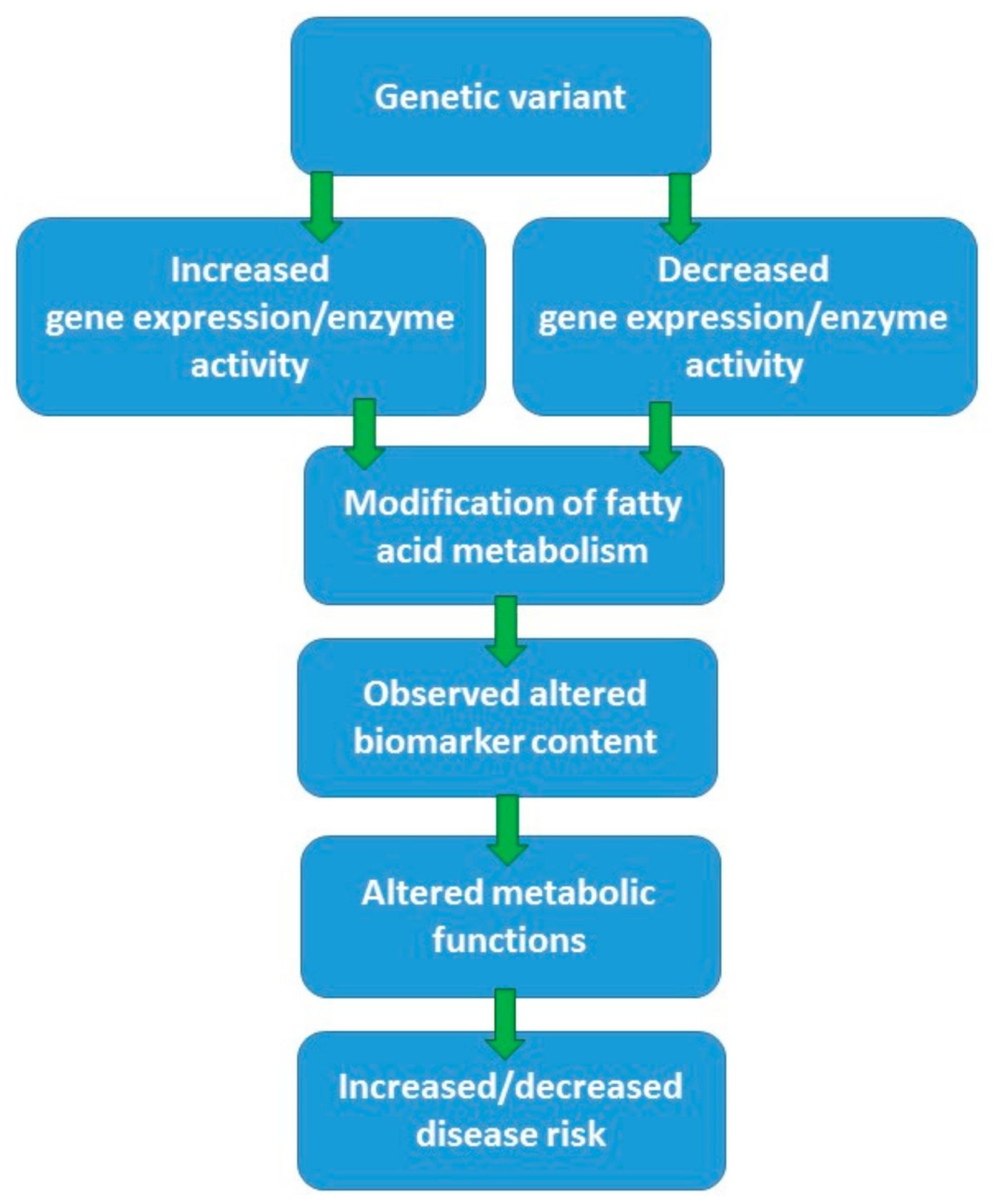

3. Genetic Variants of Fatty Acid Metabolism and Disease Risk

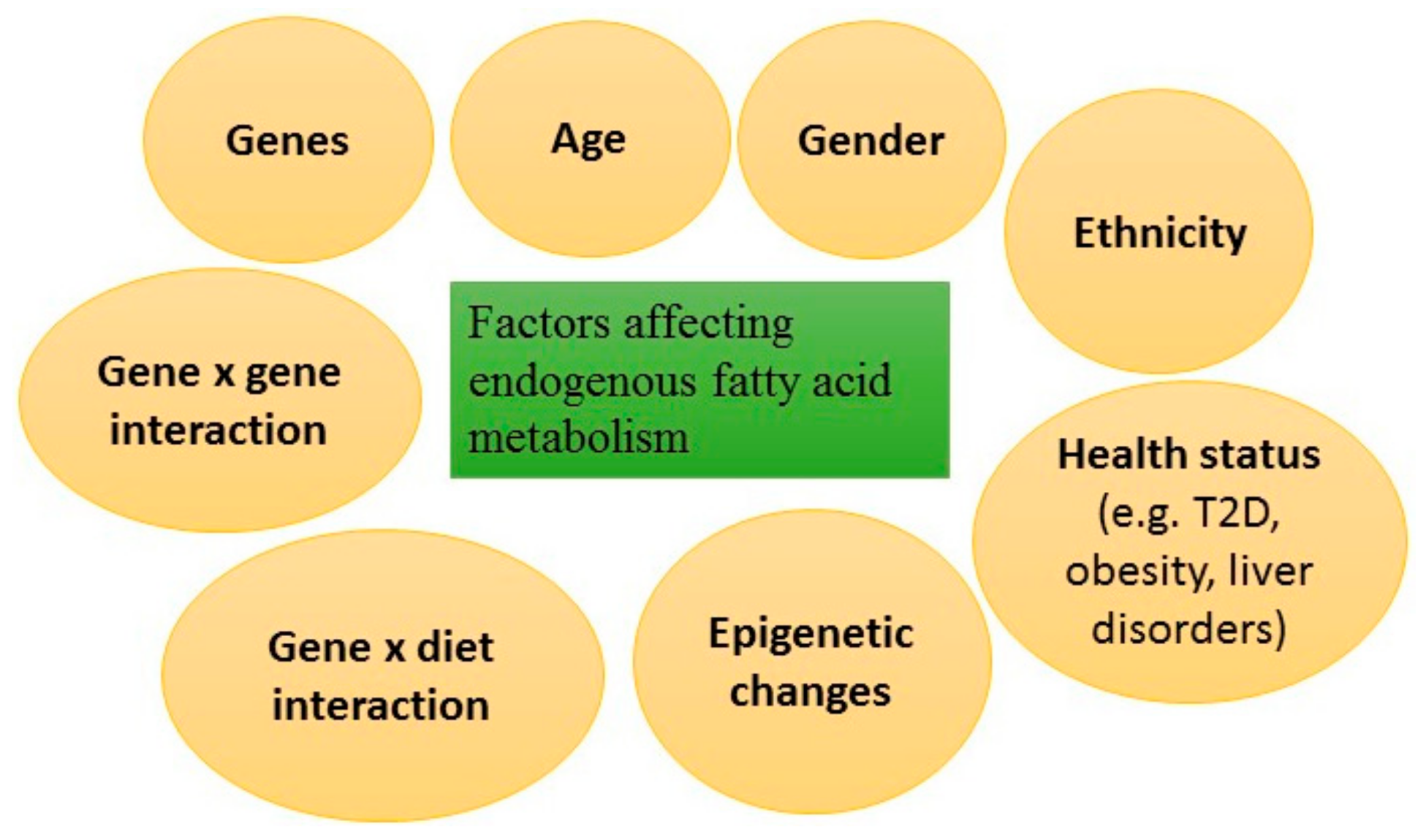

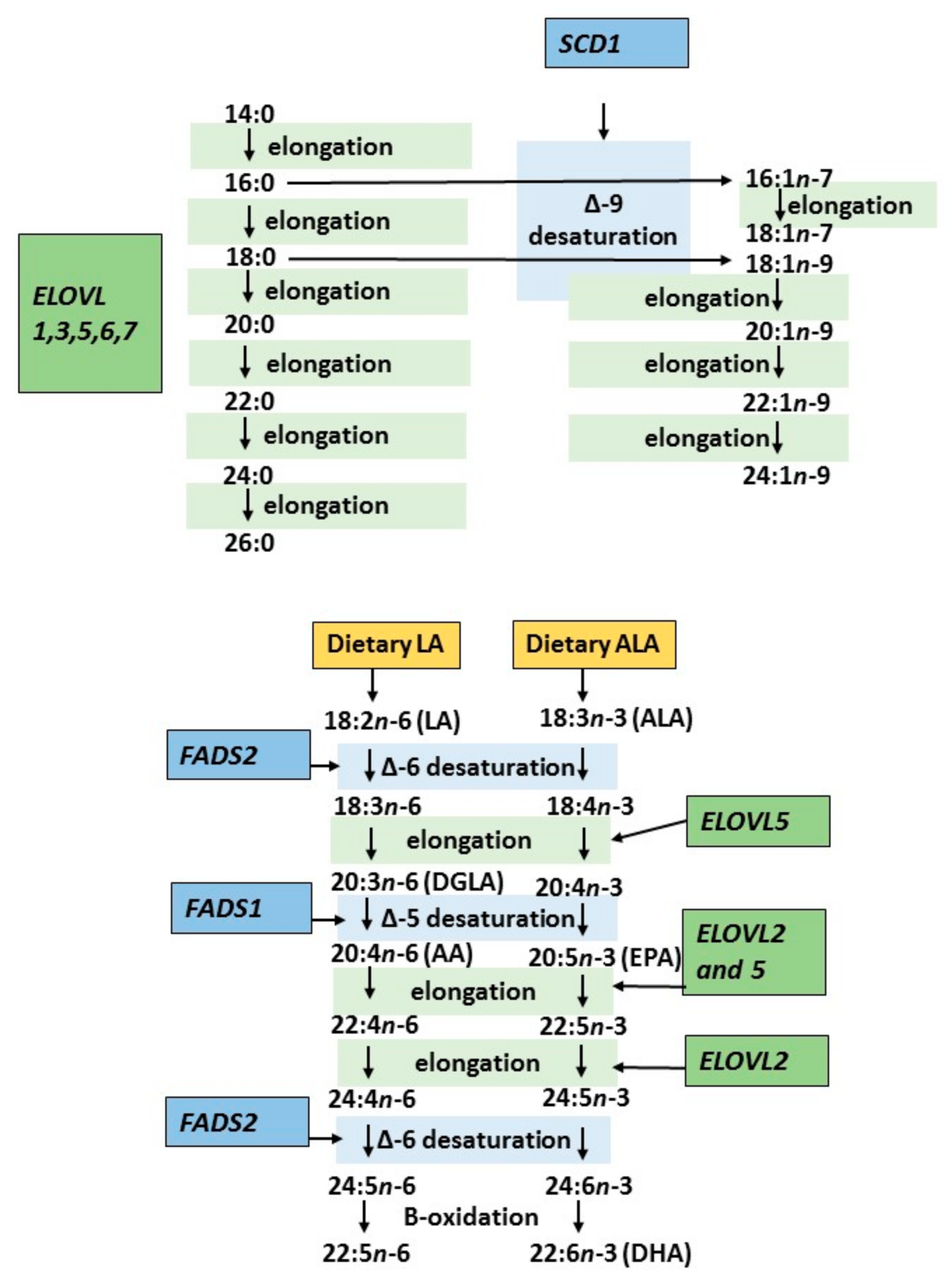

4. Genetic Regulation of Endogenous Fatty Acid Metabolism

5. Interaction between Genes and Dietary Fatty Acids

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farquhar, J.W.; Ahrens, E.H., Jr. Effects of dietary fats on human erythrocyte fatty acid patterns. J. Clin. Investig. 1963, 42, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D. Biochemical indicators of dietary fat. In Nutritional Epidemiology; Willett, W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vessby, B.; Lithell, H.; Gustafsson, I.B.; Boberg, J. Changes in the fatty acid composition of the plasma lipid esters during lipid-lowering treatment with diet, clofibrate and niceritrol. reduction of the proportion of linoleate by clofibrate but not by niceritrol. Atherosclerosis 1980, 35, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkkinen, E.S.; Agren, J.J.; Ahola, I.; Ovaskainen, M.L.; Uusitupa, M.I. Fatty acid composition of serum cholesterol esters, and erythrocyte and platelet membranes as indicators of long-term adherence to fat-modified diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, G.; Murru, E.; Banni, S.; Manca, C. Palmitic acid: Physiological role, metabolism and nutritional implications. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitkunat, K.; Schumann, S.; Nickel, D.; Hornemann, S.; Petzke, K.J.; Schulze, M.B.; Pfeiffer, A.F.; Klaus, S. Odd-Chain Fatty acids as a biomarker for dietary fiber intake: A novel pathway for endogenous production from propionate. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatian-Elahi, M.; Slimani, N.; Chajes, V.; Jenab, M.; Goudable, J.; Biessy, C.; Ferrari, P.; Byrnes, G.; Autier, P.; Peeters, P.H.; et al. Plasma phospholipid fatty acid profiles and their association with food intakes: Results from a cross-sectional study within the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozogul, Y.; Ozogul, F.; Cicek, E.; Polat, A.; Kuley, E. Fat content and fatty acid compositions of 34 marine water fish species from the mediterranean sea. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 60, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggelousis, G.; Lazos, E.S. Fatty acid composition of the lipids from eight freshwater fish species from greece. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1991, 4, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgren, H.M.; Agren, J.J.; Schwab, U.; Rissanen, T.; Hanninen, O.; Uusitupa, M.I. Incorporation of n-3 fatty acids into plasma lipid fractions, and erythrocyte membranes and platelets during dietary supplementation with fish, fish oil, and docosahexaenoic acid-rich oil among healthy young men. Lipids 1997, 32, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katan, M.B.; Deslypere, J.P.; van Birgelen, A.P.; Penders, M.; Zegwaard, M. Kinetics of the incorporation of dietary fatty acids into serum cholesteryl esters, erythrocyte membranes, and adipose tissue: An 18-month controlled study. J. Lipid Res. 1997, 38, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.; Sarda, P.; Nessmann, C.; Boulot, P.; Leger, C.L.; Descomps, B. Delta6- and delta5-desaturase activities in the human fetal liver: Kinetic aspects. J. Lipid Res. 1998, 39, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takkunen, M.; Agren, J.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M.; Uusitupa, M.; Schwab, U. Dietary fat in relation to erythrocyte fatty acid composition in men. Lipids 2013, 48, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidgren, H.M.; Louheranta, A.M.; Agren, J.J.; Schwab, U.S.; Uusitupa, M.I. Divergent incorporation of dietary trans fatty acids in different serum lipid fractions. Lipids 1998, 33, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lankinen, M.A.; Stancakova, A.; Uusitupa, M.; Agren, J.; Pihlajamaki, J.; Kuusisto, J.; Schwab, U.; Laakso, M. Plasma fatty acids as predictors of glycaemia and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2533–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Miranda, J.; Williams, C.; Lairon, D. Dietary, physiological, genetic and pathological influences on postprandial lipid metabolism. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.E.; Ordovas, J.M. Fatty acid interactions with genetic polymorphisms for cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2010, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Shen, J.; Abecasis, G.R.; Kisialiou, A.; Ordovas, J.M.; Guralnik, J.M.; Singleton, A.; Bandinelli, S.; Cherubini, A.; Arnett, D.; et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids in the inchianti study. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Kothapalli, K.S.; Brenna, J.T. Desaturase and elongase-limiting endogenous long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agren, J.J.; Valve, R.; Vidgren, H.; Laakso, M.; Uusitupa, M. Postprandial lipemic response is modified by the polymorphism at codon 54 of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, L.J.; Sacchettini, J.C.; Knowler, W.C.; Eads, J.; Paolisso, G.; Tataranni, P.A.; Mochizuki, H.; Bennett, P.H.; Bogardus, C.; Prochazka, M. An amino acid substitution in the human intestinal fatty acid binding protein is associated with increased fatty acid binding, increased fat oxidation, and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Yuan, X.; Ishiyama, S.; Koyama, K.; Ichikawa, F.; Koyanagi, A.; Koyama, W.; Nonaka, K. Association between Ala54Thr substitution of the fatty acid-binding protein 2 gene with insulin resistance and intra-abdominal fat thickness in japanese men. Diabetologia 1997, 40, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agren, J.J.; Vidgren, H.M.; Valve, R.S.; Laakso, M.; Uusitupa, M.I. Postprandial responses of individual fatty acids in subjects homozygous for the threonine- or alanine-encoding allele in codon 54 of the intestinal fatty acid binding protein 2 gene. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthier, M.T.; Couillard, C.; Prud’homme, D.; Nadeau, A.; Bergeron, J.; Tremblay, A.; Despres, J.P.; Vohl, M.C. Effects of the FABP2 A54T mutation on triglyceride metabolism of viscerally obese men. Obes. Res. 2001, 9, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, T.; Sato, N.F.; Kuromori, Y.; Miyashita, M.; Iwata, F.; Hara, M.; Harada, K.; Hattori, H. Thr-Encoding allele homozygosity at codon 54 of fabp 2 gene may be associated with impaired delta 6 desatruase activity and reduced plasma arachidonic acid in obese children. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2006, 13, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, J.C.; Gross, J.L.; Canani, L.H.; Zelmanovitz, T.; Perassolo, M.S.; Azevedo, M.J. The Ala54Thr polymorphism of the fabp2 gene influences the postprandial fatty acids in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3909–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjogren, P.; Sierra-Johnson, J.; Gertow, K.; Rosell, M.; Vessby, B.; de Faire, U.; Hamsten, A.; Hellenius, M.L.; Fisher, R.M. Fatty acid desaturases in human adipose tissue: Relationships between gene expression, desaturation indexes and insulin resistance. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warensjo, E.; Rosell, M.; Hellenius, M.L.; Vessby, B.; De Faire, U.; Riserus, U. Associations between estimated fatty acid desaturase activities in serum lipids and adipose tissue in humans: Links to obesity and insulin resistance. Lipids Health. Dis. 2009, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroger, J.; Schulze, M.B. Recent insights into the relation of delta5 desaturase and delta6 desaturase activity to the development of type 2 diabetes. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2012, 23, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahendran, Y.; Agren, J.; Uusitupa, M.; Cederberg, H.; Vangipurapu, J.; Stancakova, A.; Schwab, U.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M. Association of erythrocyte membrane fatty acids with changes in glycemia and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.; Schiller, K.; Jansen, E.H.; Boeing, H.; Schulze, M.B.; Kroger, J. Evaluation of various biomarkers as potential mediators of the association between delta5 desaturase, delta6 desaturase, and stearoyl-coa desaturase activity and incident type 2 diabetes in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition-potsdam study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yary, T.; Voutilainen, S.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Ruusunen, A.; Nurmi, T.; Virtanen, J.K. Serum N-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, delta5- and delta6-desaturase activities, and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: The kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takkunen, M.J.; Schwab, U.S.; de Mello, V.D.; Eriksson, J.G.; Lindstrom, J.; Tuomilehto, J.; Uusitupa, M.I.; DPS Study Group. Longitudinal associations of serum fatty acid composition with type 2 diabetes risk and markers of insulin secretion and sensitivity in the finnish diabetes prevention study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willer, C.J.; Schmidt, E.M.; Sengupta, S.; Peloso, G.M.; Gustafsson, S.; Kanoni, S.; Ganna, A.; Chen, J.; Buchkovich, M.L.; Mora, S.; et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Gobbo, L.C.; Imamura, F.; Aslibekyan, S.; Marklund, M.; Virtanen, J.K.; Wennberg, M.; Yakoob, M.Y.; Chiuve, S.E.; Dela Cruz, L.; Frazier-Wood, A.C.; et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid biomarkers and coronary heart disease: Pooling project of 19 cohort studies. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaittinen, M.; Mannisto, V.; Kakela, P.; Agren, J.; Tiainen, M.; Schwab, U.; Pihlajamaki, J. Interorgan cross talk between fatty acid metabolism, tissue inflammation, and fads2 genotype in humans with obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017, 25, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, T.D.; Mathias, R.A.; Seeds, M.C.; Herrington, D.M.; Hixson, J.E.; Shimmin, L.C.; Hawkins, G.A.; Sellers, M.; Ainsworth, H.C.; Sergeant, S.; et al. DNA methylation in an enhancer region of the fads cluster is associated with fads activity in human liver. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, L.M.; Howard, T.D.; Ruczinski, I.; Kanchan, K.; Seeds, M.C.; Mathias, R.A.; Chilton, F.H. Tissue-specific impact of fads cluster variants on fads1 and fads2 gene expression. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, L.; Gohlke, H.; Muller, M.; Heid, I.M.; Palmer, L.J.; Kompauer, I.; Demmelmair, H.; Illig, T.; Koletzko, B.; Heinrich, J. Common genetic variants of the fads1 fads2 gene cluster and their reconstructed haplotypes are associated with the fatty acid composition in phospholipids. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 1745–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzehak, P.; Heinrich, J.; Klopp, N.; Schaeffer, L.; Hoff, S.; Wolfram, G.; Illig, T.; Linseisen, J. Evidence for an association between genetic variants of the fatty acid desaturase 1 fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS1 FADS2) gene cluster and the fatty acid composition of erythrocyte membranes. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; Tanaka, T.; Tang, W.; Manichaikul, A.; Foy, M.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Nettleton, J.A.; King, I.B.; Weng, L.C.; Bhattacharya, S.; et al. Genetic loci associated with plasma phospholipid n-3 fatty acids: A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies from the CHARGE consortium. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumagalli, M.; Moltke, I.; Grarup, N.; Racimo, F.; Bjerregaard, P.; Jorgensen, M.E.; Korneliussen, T.S.; Gerbault, P.; Skotte, L.; Linneberg, A.; et al. Greenlandic inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation. Science 2015, 349, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlajamaki, J.; Schwab, U.; Kaminska, D.; Agren, J.; Kuusisto, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Paananen, J.; Laakso, M.; Uusitupa, M. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and the pro12ala polymorphisms of pparg regulate serum lipids through divergent pathways: A randomized crossover clinical trial. Genes Nutr. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zietemann, V.; Kroger, J.; Enzenbach, C.; Jansen, E.; Fritsche, A.; Weikert, C.; Boeing, H.; Schulze, M.B. Genetic variation of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster and N-6 PUFA composition in erythrocyte membranes in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition-potsdam study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molto-Puigmarti, C.; Plat, J.; Mensink, R.P.; Muller, A.; Jansen, E.; Zeegers, M.P.; Thijs, C. FADS1 FADS2 gene variants modify the association between fish intake and the docosahexaenoic acid proportions in human milk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1368–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porenta, S.R.; Ko, Y.A.; Gruber, S.B.; Mukherjee, B.; Baylin, A.; Ren, J.; Djuric, Z. Interaction of fatty acid genotype and diet on changes in colonic fatty acids in a mediterranean diet intervention study. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2013, 6, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roke, K.; Mutch, D.M. The role of FADS1/2 polymorphisms on cardiometabolic markers and fatty acid profiles in young adults consuming fish oil supplements. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2290–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.E.; Follis, J.L.; Nettleton, J.A.; Foy, M.; Wu, J.H.; Ma, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Manichakul, A.W.; Wu, H.; Chu, A.Y.; et al. Dietary fatty acids modulate associations between genetic variants and circulating fatty acids in plasma and erythrocyte membranes: Meta-analysis of nine studies in the charge consortium. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillingham, L.G.; Harding, S.V.; Rideout, T.C.; Yurkova, N.; Cunnane, S.C.; Eck, P.K.; Jones, P.J. Dietary oils and FADS1-FADS2 genetic variants modulate [13C] alpha-linolenic acid metabolism and plasma fatty acid composition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.H.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Manichaikul, A.; Guan, W.; Tanaka, T.; Foy, M.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Djousse, L.; Siscovick, D.; Fretts, A.M.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci associated with concentrations of four plasma phospholipid fatty acids in the de novo lipogenesis pathway: Results from the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2013, 6, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.; Steffen, B.T.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Wu, J.H.; Tanaka, T.; Manichaikul, A.; Foy, M.; Rich, S.S.; Wang, L.; Nettleton, J.A.; et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma n6 polyunsaturated fatty acids within the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology consortium. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2014, 7, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorajoo, R.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Ke, T.; Burger, A.; Chang, X.; Low, H.Q.; Guan, W.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Khor, C.C.; et al. A genome-wide association study of n-3 and n-6 plasma fatty acids in a singaporean chinese population. Genes Nutr. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, R.N.; King, I.B.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Wu, J.H.; McKnight, B.; Manichaikul, A.; Guan, W.; Sun, Q.; Chasman, D.I.; Foy, M.; et al. Genetic loci associated with circulating levels of very long-chain saturated fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Johnson, C.O.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Manichaikul, A.; Sun, Q.; Foy, M.; Wang, L.; Wiener, H.; Irvin, M.R.; et al. Genetic loci associated with circulating phospholipid trans fatty acids: A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies from the CHARGE consortium. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tintle, N.L.; Pottala, J.V.; Lacey, S.; Ramachandran, V.; Westra, J.; Rogers, A.; Clark, J.; Olthoff, B.; Larson, M.; Harris, W.; et al. A genome-wide association study of saturated, mono- and polyunsaturated red blood cell fatty acids in the framingham heart offspring study. prostaglandins leukot. essent. Fatty Acids 2015, 94, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Lemaitre, R.N.; Sun, Q.; King, I.B.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Manichaikul, A.; Rich, S.S.; Tsai, M.Y.; Chen, Y.D.; Fornage, M.; et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis of circulating odd-numbered chain saturated fatty acids: Results from the CHARGE consortium. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Innis, S.M. Genetic variants of the FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster are ASSOCIATED with altered (N-6) and (N-3) essential fatty acids in plasma and erythrocyte phospholipids in women during pregnancy and in breast milk during lactation. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 2222–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, J.; Huybrechts, I.; Spinneker, A.; Gottrand, F.; Grammatikaki, E.; Bevilacqua, N.; Vyncke, K.; Widhalm, K.; Kafatos, A.; Molnar, D.; et al. FADS1 genetic variability interacts with dietary alpha-linolenic acid intake to affect serum Non-HDL-Cholesterol concentrations in european adolescents. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, D.M.; Johnston, H.; Clarke, S.; Roke, K.; Nielsen, D.; Badawi, A.; El-Sohemy, A.; Ma, D.W.; Mutch, D.M. Polymorphisms in FADS1 and FADS2 alter desaturase activity in young caucasian and asian adults. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2011, 103, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.H.; Kwak, J.H.; Paik, J.K.; Chae, J.S.; Lee, J.H. Association of polymorphisms in FADS gene with age-related changes in serum phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids and oxidative stress markers in middle-aged nonobese men. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roke, K.; Ralston, J.C.; Abdelmagid, S.; Nielsen, D.E.; Badawi, A.; El-Sohemy, A.; Ma, D.W.; Mutch, D.M. Variation in the FADS1/2 gene cluster alters plasma n-6 PUFA and is weakly associated with hsCRP levels in healthy young adults. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2013, 89, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H.; Xu, D.; Huang, J.; Li, D. Genetic variants in desaturase gene, erythrocyte fatty acids, and risk for type 2 diabetes in chinese hans. Nutrition 2014, 30, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M.K.; Jorsboe, E.; Sandholt, C.H.; Grarup, N.; Jorgensen, M.E.; Faergeman, N.J.; Bjerregaard, P.; Pedersen, O.; Moltke, I.; Hansen, T.; et al. Identification of novel genetic determinants of erythrocyte membrane fatty acid composition among greenlanders. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takkunen, M.J.; de Mello, V.D.; Schwab, U.S.; Kuusisto, J.; Vaittinen, M.; Agren, J.J.; Laakso, M.; Pihlajamaki, J.; Uusitupa, M.I. Gene-diet interaction of a common fads1 variant with marine polyunsaturated fatty acids for fatty acid composition in plasma and erythrocytes among men. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Garza Puentes, A.; Montes Goyanes, R.; Chisaguano Tonato, A.M.; Torres-Espinola, F.J.; Arias Garcia, M.; de Almeida, L.; Bonilla Aguirre, M.; Guerendiain, M.; Castellote Bargallo, A.I.; Segura Moreno, M.; et al. Association of maternal weight with fads and elovl genetic variants and fatty acid levels- the PREOBE follow-up. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, C.; Yang, F.; Wang, S.; Zhu, S.; Ma, X. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the FADS1 gene is associated with plasma fatty acid and lipid profiles and might explain gender difference in body fat distribution. Lipids Health. Dis. 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, M.; Yoo, H.J.; Lee, A.; Jeong, S.; Lee, J.H. Associations among FADS1 rs174547, eicosapentaenoic acid/arachidonic acid ratio, and arterial stiffness in overweight subjects. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2018, 130, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhao, J.; Kothapalli, K.S.D.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Han, Y.; Mi, S.; Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; et al. A regulatory insertion-deletion polymorphism in the fads gene cluster influences PUFA and lipid profiles among chinese adults: A population-based study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hilal, M.; Alsaleh, A.; Maniou, Z.; Lewis, F.J.; Hall, W.L.; Sanders, T.A.; O’Dell, S.D.; MARINA study team. Genetic variation at the FADS1-FADS2 gene locus influences delta-5 desaturase activity and LC-PUFA proportions after fish oil supplement. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholtz, S.A.; Kerling, E.H.; Shaddy, D.J.; Li, S.; Thodosoff, J.M.; Colombo, J.; Carlson, S.E. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation in pregnancy differentially modulates arachidonic acid and DHA status across FADS genotypes in pregnancy. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2015, 94, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Athinarayanan, S.; Jiang, G.; Chalasani, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W. Fatty acid desaturase 1 gene polymorphisms control human hepatic lipid composition. Hepatology 2015, 61, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Estimated Desaturase/Elongase | Fatty Acid Ratio |

|---|---|

| Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) | 16:1n-7/16:0 |

| Delta-6-delta (D6D) | 18:3n-6/18:2n-6 |

| Delta-5-delta (D5D) | 20:4n-6/20:3n-6 |

| Elongase | 18:1n-7/16:1n-7 |

| A) GWAS Studies | |||||

| Study | Study Population and Design | Fatty Acid Biomarkers Examined | Main Findings | Comment | |

| Tanaka T et al. PLoS Genet 2009. [18] | InCHIANTI Study (Chianti region of Tuscana, Italy, n = 1075) and GOLDN (predominantly Caucasian, n = 1076) replication study | PUFAs in plasma in CHIANTI study and in erythrocytes in GOLDN study | FADS genetic cluster marker (FADS1, FADS2, FADS3) in chromosome 11 associated with AA, EDA, and EPA, and EVOLV2 genetic marker in chromosome 6 with EPA. | First GWAS with replication data. The ELOVL2 SNP was associated with DPA and DHA but not with EPA in GOLDN replication study. | |

| Lemaitre RN et al. PLoS Genet 2011. [41] | Five cohorts (n = 8866) of European ancestry (CHARGE consortium). In addition, African (n = 2547), Chinese (n = 633), and Hispanic ancestry (n = 661) study populations were examined. | Four major n-3 PUFAs (ALA, EPA, DPA, DHA) in plasma PL | Minor alleles of FADS1 and FADS2 associated with higher ALA, but lower EPA and DPA. Minor alleles of SNPs in ELOVL2 were associated with higher EPA and DPA and lower DHA content. | A novel association of DPA with several SNPs in GCKR (glucokinase regulator) was reported. Results on FADS1 were similar regardless of ancestry studied. | |

| Wu et al. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013. CHARGE consortium [50] | European Ancestry (n = 8961) | Plasma levels of 16:0, 18:0, 16:1n-7, 18:1n-9 | ALG14 polymorphisms were associated with higher 16:0 and lower 18:0. FADS1 and FADS2 polymorphisms were associated with higher 16:1n-7 and 18:1n-9 and lower 18:0. LPGAT1 polymorphisms were associated with lower 18:0. GCKR and HIF1AN polymorphisms were associated with higher 16:1n-7, whereas PKD2L1 and a locus on chromosome 2 (not near known genes) were associated with lower 16:1n-7. | Polymorphisms in 7 novel loci were associated with circulating levels of ≥1 of 16:0, 18:0, 16:1n-7, 18:1n-9. | |

| Guan et al. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014. [51] | White adults (n = 8631) | Total plasma or plasma PL n-6 PUFAs | Novel regions were identified on chromosome 10 associated with LA (rs10740118; near NRBF2); on chromosome 16 with LA, GLA, dihomo-GLA, and AA (rs16966952; NTAN1); and on chromosome 6 with adrenic acid after adjustment for AA (rs3134950; AGPAT1). Previous findings of the FADS cluster on chromosome 11 with LA and AA were confirmed. | ||

| Dorajoo R et al. Genes Nutr. 2015. [52] | Singaporean Chinese population (n = 1361) | Plasma PUFAs | Genome-wide associations with ALA, all four n-6 PUFAs, and delta-6 desaturase activity at the FADS1/FADS2 locus. These associations were independent of dietary intake of PUFAs. | Genetic loci that influence plasma concentrations of n-3 and n-6 PUFAs are shared across different ethnic groups. | |

| Fumagalli M et al. Science 2015. [42] | Inuits (n = 191), European (n = 60), and Han Chinese (n = 44) individuals | Erythrocyte membrane fatty acids | FADS1, FADS2, FADS3, and SNPs 7115739, rs174570 (among others) had positive association with ETA, but negative associations with EPA and DPA; no effect on DHA content. | Novel genes and polymorphisms were identified in Inuits that may suggest genetic and physiological adaptation to a high-omega-3-PUFA diet; associations with height and weight were also found. | |

| Lemaitre et al. J Lipid Res 2015. [53] | European ancestry (n = 10,129) | Plasma PL and Erythrocyte levels of VLSFA (20:0, 22:0, 24:0) | The SPTLC3 (serine palmitoyl-transferase long-chain base subunit 3) variant at rs680379 was associated with higher 20:0. The CERS4 (ceramide synthase 4) variant at rs2100944 was associated with higher levels of 20:0 and in analyses that adjusted for 20:0, with lower levels of 22:0 and 24:0. | SPTLC3 is a gene involved in the rate-limiting step of de novo sphingolipid synthesis. | |

| Mozaffarian et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2015. CHARGE consortium [54] | Meta-analysis of GWA studies (n = 8013) | Erythrocyte of PL trans fatty acids and 31 SNPs in or near the FADS1 and FADS2 cluster | Genetic regulation of cis/trans-18:2 by the FADS1/2 cluster. | Trans fatty acids. | |

| Tintle NL et al. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2015. [55] | Framingham Offspring Study (n = 2633) | 14 red blood cell fatty acids | Novel associations between (1) AA and PCOLCE2 (regulates apoA-I maturation and modulates apoA-I levels), and (2) oleic and linoleic acid and LPCAT3 (mediates the transfer of fatty acids between glycerolipids). Also, previously identified strong associations between SNPs in the FADS and ELOVL regions were replicated. | Multiple SNPs explained 8–14% of the variation in 3 high-abundance (>11%) fatty acids, but only 1–3% in 4 low-abundance (<3%) fatty acids, with the notable exception of DGLA acid with 53% of variance explained by SNPs. | |

| de Oliveira Otto MC et al. CHARGE consortium. PLoS One 2018. [56] | Meta-analysis of GWA studies (n = 11,494); individuals of European descent | 15:0, 17:0, 19:0, and 23:0 (OCSFA) in plasma PL and erythrocytes | SNP MYO10 rs 13361131 associated with 17:0 level, DLEU1 rs12874278 and rs 17363566 associated with 19:0 level. Using candidate gene approach, a few other SNPs also associated with 17:0 and 23:0 levels. | Circulating levels of OCSFA are predominantly influenced by nongenetic factors. | |

| B) Candidate Gene Studies | |||||

| Study | Study Population and Design | Fatty Acid Biomarkers Examined | Genes Examined | Main Findings | Comment |

| Schaeffer L et al. Hum Mol Genet 2006. [39] | N = 727 from Erfurt, Germany, from The European Community Respiratory Health Survey I (ECRHS I), cross-sectional | PUFAs in plasma PL | Haplotypes of FADS1 and FADS2 region | Haplotypes of FADS1 and FADS2 region associated with AA and many other long-chain n-6 and n-3 fatty acids (e.g., LA, GLA, and EPA and DPA. | Mostly decreased levels of PUFAs associated with minor alleles of FADS1 and FADS2. |

| Xie L and Innis SM. J Nutr 2008. [57] | 69 pregnant women in Canada and breast milk for a subset of 54 women exclusively breast-feeding at 1 month postpartum, cross-sectional | Plasma phospholipid and erythrocyte ethanolamine phosphoglyceride (EPG) (n-6) and (n-3) fatty acids | FADS1/FADS2 rs174553, rs99780, rs174575, and rs174583 | Minor allele homozygotes of rs174553 (GG), rs99780 (TT), and rs174583 (TT) had lower AA but higher LA in plasma phospholipids and erythrocyte EPG and decreased (n-6) and (n-3) fatty acid product/precursor ratios at 16 and 36 weeks of gestation. | Breast milk fatty acids were influenced by genotype, with significantly lower 14:0, AA, and EPA but higher 20:2(n-6) in the minor allele homozygotes of rs174553, rs99780, and rs174583 and lower AA, EPA, DPA, and DHA in the minor allele homozygotes of rs174575. |

| Rzehak P et al. Br J Nutr 2009. [40] | Bavarian Nutrition survey II, Germany, cross-sectional, (n = 163 and n = 535) | Phospholipid PUFA in plasma (n = 163), erythrocyte membranes (n = 535) | FADS1 and FADS2 haplotypes | Replication of FADS1 and FADS2 haplotypes associations in phospholipids (Schaeffer et al. 2006) and associations with PUFA in membranes. | Association with cell membranes was a novel finding. No associations with omega-3 PUFA. |

| Molto-Puigmarti C et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2010. [45] | KOALA Birth Cohort Study in the Netherlands. Plasma samples were collected at 36th gestational week in pregnant women (N = 309) and milk samples at 1 month postpartum. | Plasma phospholipids and milk DHA proportion | FADS1 rs174561, FADS2 rs174575, and intergenic rs3834458 | A higher fish (or fish oil) intake compensated for the lower DHA proportions in plasma phospholipids irrespective of genotype but not in the milk from women with minor allele carriers of selected gene variants. | The study confirms earlier studies with regard to PUFA associations with minor allele carriers. Novelty of this study was gene–diet interaction regarding milk fat; DHA content remained unchanged with increasing fish/fish oil intake in women homozygous for minor allele. |

| Zietemann V et al. Br J Nutr 2010. [44] | A random sample of 2066 participants from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study, cross-sectional | Erythrocyte membrane fatty acids and estimated desaturase activity | rs174546 genetic variation (reflecting genetic variation in the FADS1/FADS2 gene cluster) | Higher proportions of LA, EDA, and DGLA and lower proportions of GLA, AA, and DTA for the minor allele carriers. The estimated activities of FADS1 and FADS2 strongly decreased with minor T-allele. | Interaction with diet; dietary n-6/n-3 ratio was suggested to modify the association between the FADS1/FADS2 genotype and the estimated D5D activity. |

| Dumont J et al. J Nutr 2011. [58] | European adolescents, HELENA study (n = 573), cross-sectional | Dietary intake of LA and ALA ALA, PUFA levels in serum PL Serum concentrations of TG, cholesterol, and lipoproteins | FADS1 rs174546 | The associations between FADS1 rs174546 and concentrations of PUFA, TG, cholesterol, and lipoproteins were not affected by dietary LA intake. Similarly, the association between the FADS1 rs174546 polymorphism and serum phospholipid concentrations of ALA or EPA was not modified by dietary ALA intake. In contrast, the rs174546 minor allele was associated with lower total cholesterol concentrations and non-HDL cholesterol concentrations in the high-ALA-intake group but not in the low-ALA-intake group. | These results suggest that dietary ALA intake modulates the association between FADS1 rs174546 and serum total and non-HDL cholesterol concentrations at a young age. |

| Merino et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2011. [59] | Toronto Nutrigenomics and Health study, (Caucasians n = 78, Asian, n = 69), cross-sectional | Plasma fatty acids | FADS1 and FADS2 genotypes (19 SNPs) | The most significant association was between the FADS1 rs174547 and AA/LA in both Caucasians and Asians. Although the minor allele for this SNP differed between Caucasians (T) and Asians (C), carriers of the C allele had a lower desaturase activity than carriers of the T allele in both groups. | |

| Hong et al. Clin Interv Aging 2013. [60] | 3 years follow-up study, nonobese men in South Korea (n = 122) | Serum PL PUFAs | near FADS1 rs174537; FEN1 rs174537G; FADS2 rs174575 and rs2727270; FADS3 rs1000778 | The minor variants of rs174537 and rs2727270 were significantly associated with lower concentrations of long-chain PUFAs. | FADS polymorphisms can affect age-associated changes in serum phospholipid long-chain PUFAs, Δ5-desaturase activity, and oxidative stress. |

| Roke K et al. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2013. [61] | Cross-sectional study, healthy young adults in Canada (n = 878) | Plasma levels of LA, GLA, DGLA, and AA | FADS1/2 rs174579, rs174593, rs174626, rs526126, rs968567 and rs17831757 | Several SNPs were associated with circulating levels of individual FAs and desaturase indices, with minor allele carriers having lower AA levels and reduced desaturase indices. | A single SNP in FADS2 (rs526126) was weakly associated with hsCRP. |

| Huang et al. Nutrition 2014. [62] | T2DM patients (n = 758) and healthy individuals (n = 400) in Han Chinese, cross-sectional | Erythrocyte PL Fatty acids | Genetic variants in the FADS gene cluster | Minor allele homozygotes and heterozygotes of rs174575 and rs174537 had lower AA levels in healthy individuals. Minor allele homozygotes and heterozygotes of rs174455 in FADS3 gene had lower levels of DPA, AA, and Δ5desaturase activity in patients with T2DM. | |

| Smith CE et al. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015. [48] | Updated meta-analysis of CHARGE consortium (n = 11,668) evaluating interactions between dietary PUFAs and selected genetic variants of 5 genes | Total plasma, phospholipids or erythrocyte membranes ALA, EPA, DHA, and DPA Dietary PUFA | FADS1 rs174538 and rs174548; AGPAT3 rs7435; PDXDC1 rs4985167; GCKR rs780094; ELOVL2 rs3734398 | Primary aim was to examine gene–diet interactions regarding PUFAs. No significant interactions were found after corrections. | Fatty acid compartments affected the results, and, e.g., FADS1 interaction terms for dietary ALA vs plasma phospholipids (negative) and erythrocytes (positive) were opposite. |

| Andersen et al. PLoS Genet 2016. [63] | Cross-sectional, Greenlanders (n = 2626) | 22 FAs in the PL fraction in erythrocytemembranes | ACSL6 rs76430747; DTD1 rs6035106; CPT1A rs80356779; FADS2 rs174570; LPCAT3 rs2110073; CERS4 rs11881630 | Novel loci were identified on chromosomes 5 and 11, showing strongest association with oleic acid (ACSL6) and DHA (DTD1), respectively. For a missense variant (in CPT1A), a number of novel FA associations were identified; the strongest with 11-eicosenoic acid. | Novel loci associating with FAs in the PL fraction of erythrocytemembranes were identified in Greenlanders. For variants in FADS2, LPCAT3, and CERS4, known FA associations were replicated. |

| Takkunen M et al. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016. [64] | 962 men from the METSIM study and Kuopio Obesity Surgery Study participants (n = 240) in Finland, cross-sectional | Fatty acid composition in erythrocyte and plasma PL, CE, and TG | Hepatic expression of FADS1 (rs174547/rs174550) | A common FADS1 variant (rs 174550) showed nominally significant gene–diet interactions between EPA in erythrocytes, and plasma CE and TG and dietary intakes. | Minor allele (C) of FADS1 (rs174547) was strongly associated with reduced hepatic mRNA expression. High intake of EPA and DHA may reduce D5D activity in the liver. |

| de la Garza Puentes A et al. PLoS ONE 2017. [65] | PREOBE cohort in Spain (n = 180), 24 weeks of gestation, cross-sectional | Plasma PL FAs | 7 SNPs in FADS1, 5 in FADS2, 3 in ELOVL2 and 2 in ELOVL5 | Normal-weight women who were minor allele carriers of FADS SNPs had lower levels of AA, lower AA/DGLA and AA/LA indices, and higher levels of DGLA compared to major homozygotes. Among minor allele carriers of FADS2 and ELOVL2 SNPs, overweight/obese women showed a higher DHA/EPA index than the normal-weight group. | Maternal weight modifies the effect of genotype on FA levels. |

| Guo H et al. Lipids Health Dis 2017. [66] | 951 Chinese adults, cross-sectional | Plasma PL FAs FADS1 rs174547 | FADS1 rs174547 | The rs174547 C minor allele was associated with a higher proportion of LA, lower AA and DHA, as well as lower delta-6-desaturase and delta-5-desaturase activities. | Confirms earlier finding in Chinese population. |

| Kim et al. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2018. [67] | Three-year prospective cohort study in Korea, 287 healthy subjects | Plasma PUFA levels | FADS1 rs174547 | The minor allele of the FADS1 rs174547 associated with age-related decrease in the EPA/AA ratio among overweight subjects. | The minor allele of the FADS 1 rs174547 associated with increase in arterial stiffness among overweight subjects. |

| Li et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2018. [68] | 1504 healthy Chinese adults, cross-sectional | Plasma PUFA concentration | FADS2 rs66698963 | The rs66698963 genotype is associated with AA concentration and AA to EPA+DHA ratio. | Genotype also affected triglyceride and HDL cholesterol concentrations. |

| C) Intervention Studies | |||||

| Study | Study Population and Design | Fatty Acid Biomarkers Examined | Genes Examined | Main Findings | COMMENT |

| Al-Hilal M et al. J Lipid Res 2013. [69] | RCT in United Kingdom (n = 310) Supplementation of EPA + DHA 1) 0.45 g/day 2) 0.9 g/day 3) 1.8 g/day 4) placebo for 6 months | Plasma and erythrocyte PUFAs | FADS1/FADS2 rs174537, rs174561, and rs3834458 | s174537, rs174561, and rs3834458 in the FADS1–FADS2 gene cluster were strongly associated with proportions of LC-PUFAs and desaturase activities estimated in plasma and Ery. In a randomized controlled dietary intervention, increasing EPA and docosahexaenoic acid DHA intake significantly increased D5D and decreased D6D activity after doses of 0.45, 0.9, and 1.8 g/day for six months. Interaction of rs174537 genotype with treatment was a determinant of D5D activity estimated in plasma. | Different sites at the FADS1–FADS2 locus appear to influence D5D and D6D activity, and rs174537 genotype interacts with dietary EPA+DHA to modulate D5D. |

| Gillingham LG et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2013. [49] | 36 hyperlipidemic individuals in Canada, randomized cross-over design with 3 experimental diets for 4 weeks 1) Flax seed oil 2) High canola oil 3) Western diet Only a few persons with minor allele of a given gene | Plasma FAs and (U-13C) ALA metabolism | SNPs for FADS1, FADS2 and ELOVL2 | Subjects homozygous for the minor allele of FADS1/FADS2 had lower plasma composition of AA and AA/LA ratio in comparison with the major allele carriers after consumption of each experimental diet. ELOVL2 had no effect on PUFAs. | Increasing ALA intake with a diet enriched in flaxseed oil in minor allele homozygotes resulted in an increased plasma composition of EPA beyond that of major allele homozygotes consuming a typical western diet. |

| Porenta SR et al. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013. [46] | 108 individuals with increased risk of colon cancer in USA, RCT for 6 months with two intervention diets: 1) Mediterranean type (MedD) 2) Heathy Eating Diet | Serum and colonic mucosa fatty acids | FADS1/FADS2 minor allele SNPs (rs174556, rs174561, rs174537, rs3834458) | At 6 months, an increase in colonic AA in the Healthy Eating diet arm was found, while colon AA concentrations remained fairly constant in the MedD group in persons with major alleles in the FADS1/2 gene cluster. | These results suggest gene–diet interaction in fatty acid metabolism related to different response to diets, but in individuals with major alleles of the FADS cluster. |

| Roke K and Mutch DM. Nutrients 2014. [47] | 12 young men in Canada, 12 week intervention with fish oil capsules with 8 week wash-out; no control group | Fatty acid analysis from serum and erythrocytes | FADS1/FADS2 (rs174537, rs174576) | Marked increase in serum and erythrocyte EPA and DHA. Elevation in RBC was sustained for 8 weeks during wash-out. | No significant gene × fish oil interaction, but % change in minor allele carriers of FADS1/FADS2 had a greater increase in RBC EPA levels. |

| Scholtz SA et al. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2015. [70] | Intervention, pregnant women (n = 205) in USA 1) Supplementation with 600 mg per day of DHA 2) Placebo for the last two trimesters of pregnancy | Plasma and RBC PL AA and DHA | FADS1 rs174533 and FADS2 rs174575 | DHA but not the placebo decreased the AA status of minor allele homozygotes of both FADS SNPs but not major allele homozygotes at delivery. | |

| Lankinen et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2018. (in press) | Intervention, men with FADS1 rs174550 TT or CC genotype (n = 59) in Finland High-LA diet for 4 weeks | Plasma PL and CE fatty acids | FADS1 rs174550 | There was a significant increase in the LA proportion in PL and CE in both genotype groups. A significant interaction between intervention and genotype was observed in AA, (decreased in CC genotype, but remained unchanged (in PL) or decreased only slightly (in CE) in TT genotype). | The response to higher LA intake in hsCRP was different between the genotypes. Individuals with the rs174550-TT genotype had a trend towards decreased hsCRP, while individuals with the rs174550-CC genotype had a trend towards increased hsCRP (significant diet × genotype interaction). |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lankinen, M.; Uusitupa, M.; Schwab, U. Genes and Dietary Fatty Acids in Regulation of Fatty Acid Composition of Plasma and Erythrocyte Membranes. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111785

Lankinen M, Uusitupa M, Schwab U. Genes and Dietary Fatty Acids in Regulation of Fatty Acid Composition of Plasma and Erythrocyte Membranes. Nutrients. 2018; 10(11):1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111785

Chicago/Turabian StyleLankinen, Maria, Matti Uusitupa, and Ursula Schwab. 2018. "Genes and Dietary Fatty Acids in Regulation of Fatty Acid Composition of Plasma and Erythrocyte Membranes" Nutrients 10, no. 11: 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111785

APA StyleLankinen, M., Uusitupa, M., & Schwab, U. (2018). Genes and Dietary Fatty Acids in Regulation of Fatty Acid Composition of Plasma and Erythrocyte Membranes. Nutrients, 10(11), 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111785