Assessing the Impact of T-Mart Adjacency Effect Correction on Turbidity Retrieval from Landsat 8/9 and Sentinel-2 Imagery (Case Study: St. Lawrence River, Canada)

Highlights

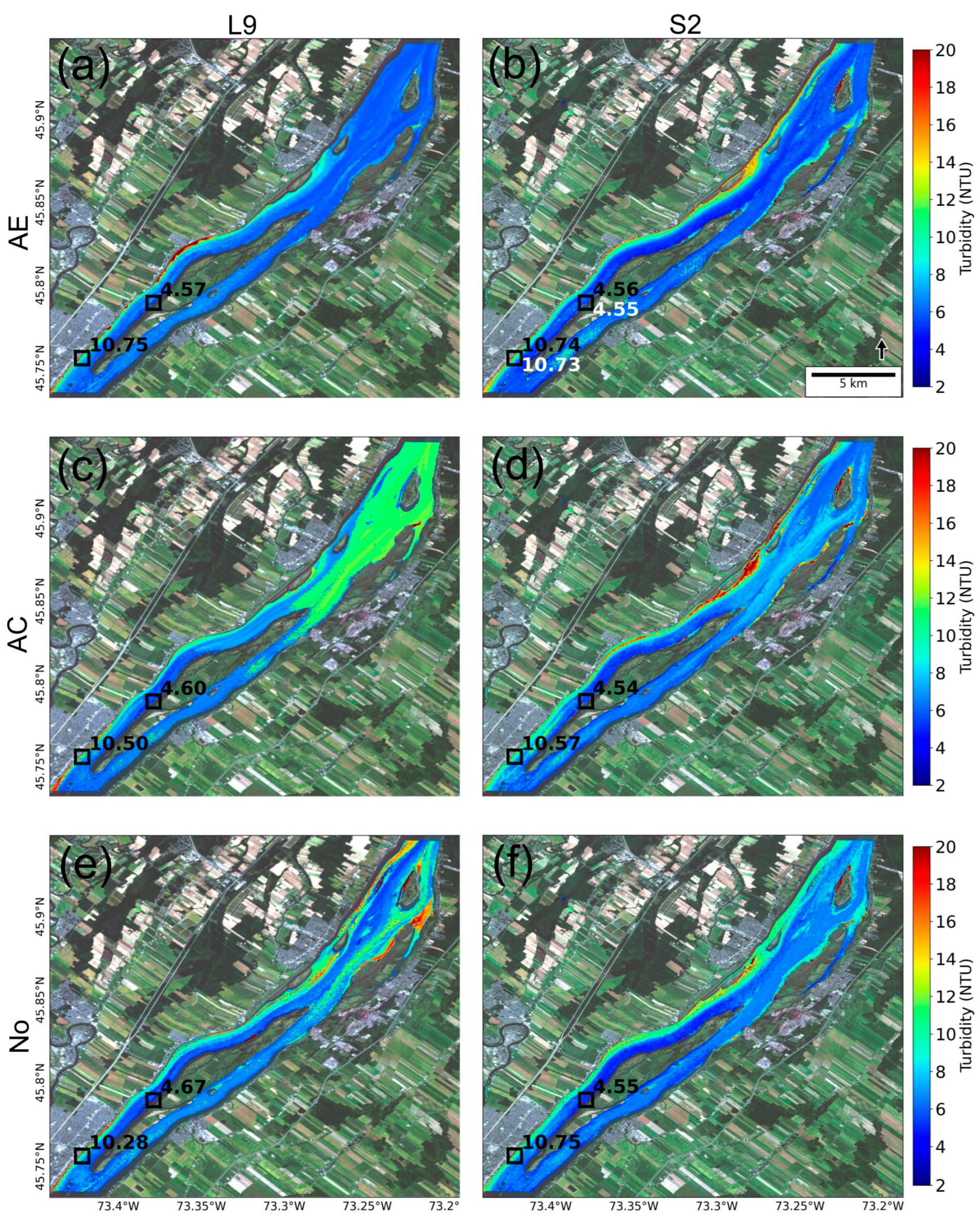

- Applying adjacency effect correction with T-Mart prior to atmospheric correction with ACOLITE improved LightGBM models that use satellite imagery to retrieve turbidity in the St. Lawrence River.

- Models using imagery pre-processed with T-Mart create smoother turbidity maps, reducing noise from clouds and shoreline reflectance.

- Improved accuracy near the shoreline demonstrates that adjacency effect correction is essential for reliable turbidity retrieval in environments where adjacency effects are strong.

- Incorporating T-Mart into pre-processing pipelines can improve the performance of machine learning models, supporting more accurate monitoring of turbidity in inland waters.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Atmospheric heterogeneity, caused by urban aerosols and pollution, invalidates the atmospheric conditions assumed in radiative transfer modeling.

- Inland waters typically exhibit moderate-to-high turbidity, which causes non-negligible reflectance in the near-infrared (NIR) region. This invalidates assumptions used in AC methods that rely on NIR bands to derive the aerosol type (i.e., the composition and size distribution of atmospheric particles) and optical thickness (a measure of the extent to which aerosols and molecules attenuate light as it passes through the atmosphere), potentially leading to the overcorrection of Rw in the visible spectrum [6,7].

- The Adjacency Effect (AE), the scattering of light from nearby bright surfaces (e.g., land, clouds) into the sensor’s field of view, thereby contaminating the reflectance of water pixels, is strong for most inland waters due to their close proximity to land [8].

- using raw TOA reflectance (No pre-processing option);

- using Rw derived from DSF (AC pre-processing option); and

- using Rw derived from DSF after pre-processing with T-Mart (AE pre-processing option).

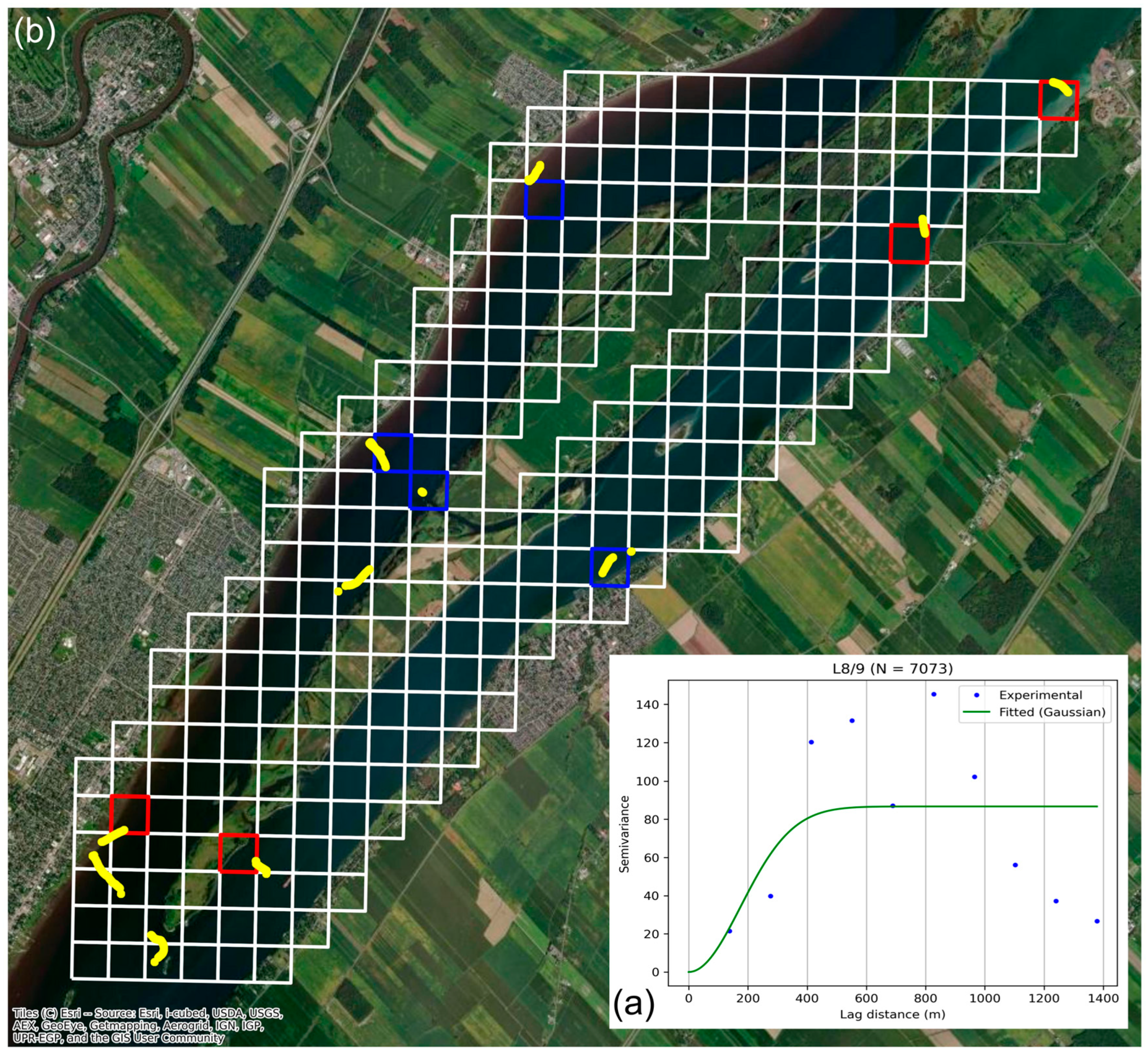

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

2.2. In Situ and Satellite Data

3. Methodology

3.1. Atmospheric Correction

3.2. Dataset Creation

3.3. Regression Model

3.4. Performance Metrics

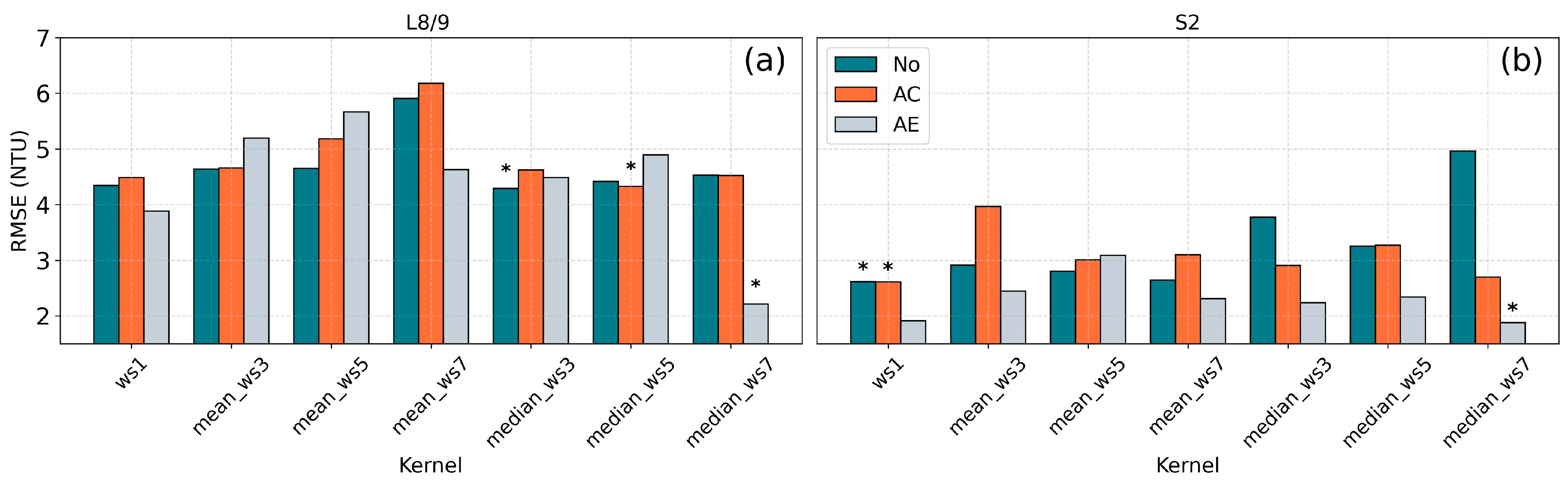

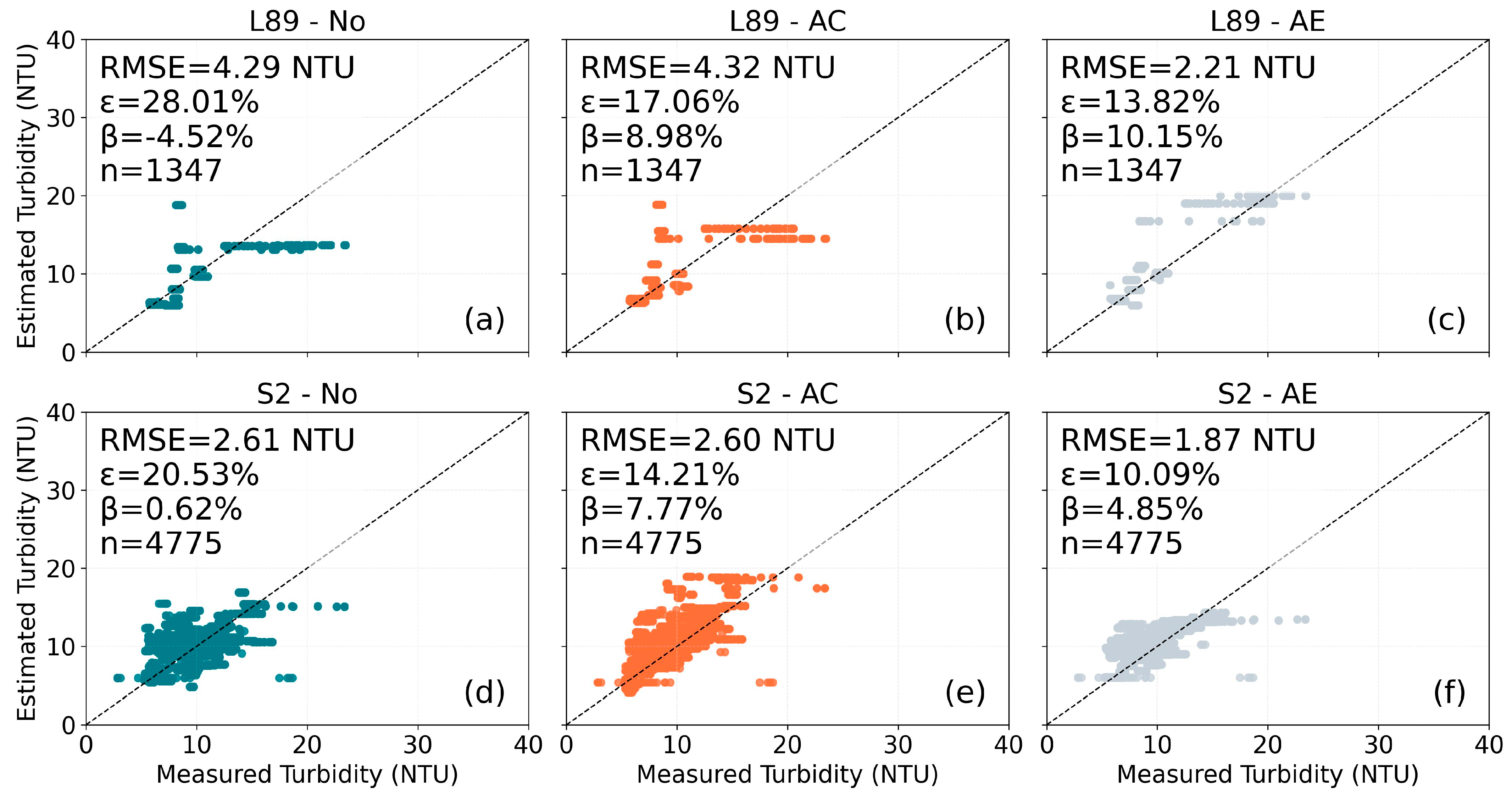

4. Results

4.1. Matchups

4.2. Turbidity Retrieval

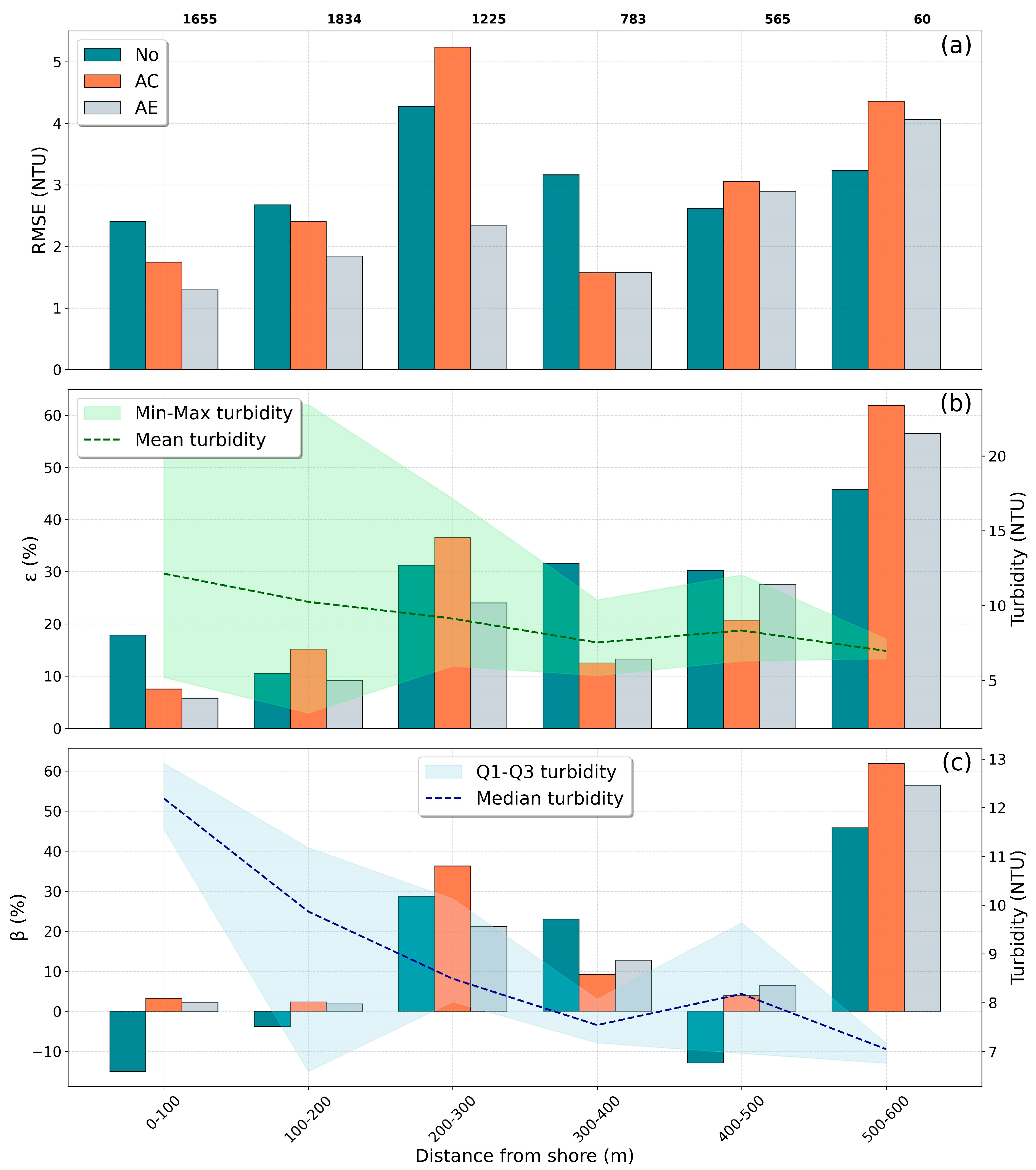

4.3. Variability of Correction Results with Distance to Shore

4.4. Visual Comparison

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance Comparison Among Pre-Processing Options

5.2. Variation in Scenario Performance with Shoreline Distance

5.3. Visual Assessment of Turbidity Maps

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ansari, M.; Knudby, A.; Amani, M.; Sawada, M. Retrieving Inland Water Quality Parameters via Satellite Remote Sensing: Sensor Evaluation, Atmospheric Correction, and Machine Learning Approaches. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.E. Turbidity as a Control on Phytoplankton Biomass and Productivity in Estuaries. Cont. Shelf Res. 1987, 7, 1367–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, R.; Ma, Y.; Shen, M.; You, Y.; Hai, K.; Baqa, M.F. Remote Sensing Retrieval of Turbidity in Alpine Rivers Based on High Spatial Resolution Satellites. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.R.; Ogashawara, I.; Gitelson, A.A. Bio-Optical Modeling and Remote Sensing of Inland Waters; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-804654-8. [Google Scholar]

- IOCCG. Atmospheric Correction for Remotely-Sensed Ocean-Colour Products; IOCCG Report Series; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Carder, K.L.; Muller-Karger, F.E. Atmospheric Correction of SeaWiFS Imagery over Turbid Coastal Waters: A Practical Method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, K.G.; Ovidio, F.; Rijkeboer, M. Atmospheric Correction of SeaWiFS Imagery for Turbid Coastal and Inland Waters. Appl. Opt. 2000, 39, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanré, D.; Deschamps, P.Y.; Duhaut, P.; Herman, M. Adjacency Effect Produced by the Atmospheric Scattering in Thematic Mapper Data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1987, 92, 12000–12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Mangin, A.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Smith, B.; Alikas, K.; Arai, K.; Barbosa, C.; Bélanger, S.; Binding, C.; Bresciani, M.; et al. ACIX-Aqua: A Global Assessment of Atmospheric Correction Methods for Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 over Lakes, Rivers, and Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q.; Ruddick, K. Atmospheric Correction of Metre-Scale Optical Satellite Data for Inland and Coastal Water Applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q. Adaptation of the Dark Spectrum Fitting Atmospheric Correction for Aquatic Applications of the Landsat and Sentinel-2 Archives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 225, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, Y.O. Modelling Reservoir Turbidity from Medium Resolution Sentinel-2A/MSI and Landsat-8/OLI Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XXII, SPIE, Bellingham, WA, USA, 20 September 2020; Volume 11528, pp. 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Song, K.; Wen, Z.; Shang, Y.; Li, S.; Fang, C.; Tao, H. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Estimating Global Lake Clarity With Landsat TOA Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4206514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Shen, F.; Sklenička, P.; Vymazal, J.; Baxa, M.; Chen, Z. Machine Learning for Cyanobacteria Inversion via Remote Sensing and AlgaeTorch in the Třeboň Fishponds, Czech Republic. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begliomini, F.N.; Barbosa, C.C.F.; Martins, V.S.; Novo, E.M.L.M.; Paulino, R.S.; Maciel, D.A.; Lima, T.M.A.; O’Shea, R.E.; Pahlevan, N.; Lamparelli, M.C. Machine Learning for Cyanobacteria Mapping on Tropical Urban Reservoirs Using PRISMA Hyperspectral Data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 204, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieronymi, M.; Krasemann, H.; Mueller, D.; Brockmann, C.; Ruescas, A.; Stelzer, K.; Nechad, B.; Ruddick, K.; Simis, S.; Tilstone, G.; et al. Ocean Colour Remote Sensing of Extreme Case-2 Waters. Proc. ESA Living Planet Symp. 2016, SP-740, Sco 3-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Knudby, A.; Lapen, D. Topography-adjusted Monte Carlo simulation of the adjacency effect in remote sensing of coastal and inland waters. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2023, 303, 108589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Vanhellemont, Q. A Generalised Physics-Based Correction for Adjacency Effects. Appl. Opt. 2025, 64, 2719–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Bélanger, S. Genetic Algorithm for Atmospheric Correction (GAAC) of Water Bodies Impacted by Adjacency Effects. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 317, 114508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Knudby, A.; Pahlevan, N.; Lapen, D.; Zeng, C. Sensor-Generic Adjacency-Effect Correction for Remote Sensing of Coastal and Inland Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 315, 114433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Noh, H.; Seo, I.W.; Park, Y.S. Effects of Spectral Variability Due to Sediment and Bottom Characteristics on Remote Sensing for Suspended Sediment in Shallow Rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ruan, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Pang, Y.; Gao, Y. A Review of Remote Sensing-Based Water Quality Monitoring in Turbid Coastal Waters. Intell. Mar. Technol. Syst. 2025, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Knudby, A.; Homayouni, S. River Salinity Mapping through Machine Learning and Statistical Modeling Using Landsat 8 OLI Imagery. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 6981–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.M.; Salehi, B.; Niroumand-Jadidi, M.; Mahdianpari, M. Mapping Water Clarity in Small Oligotrophic Lakes Using Sentinel-2 Imagery and Machine Learning Methods: A Case Study of Canandaigua Lake in Finger Lakes, New York. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4674–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.; Hasan, M.; An, K.-G. Advancing Reservoirs Water Quality Parameters Estimation Using Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Satellite Data with Machine Learning Approaches. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, X.; He, B.; Feng, Q.; Yang, F.; Liu, H.; Kutser, T.; Xu, M.; Xiao, F.; et al. Spatial-Temporal Distribution of Labeled Set Bias Remote Sensing Estimation: An Implication for Supervised Machine Learning in Water Quality Monitoring. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2024, 131, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjovu, G.E.; Stephen, H.; James, D.; Ahmad, S. Measurement of Total Dissolved Solids and Total Suspended Solids in Water Systems: A Review of the Issues, Conventional, and Remote Sensing Techniques. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjovu, G.E.; Stephen, H.; Ahmad, S. A Machine Learning Approach for the Estimation of Total Dissolved Solids Concentration in Lake Mead Using Electrical Conductivity and Temperature. Water 2023, 15, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.; Knudby, A.; Wu, Y.; Ansari, M. A Case Study Comparing Approaches to Mask Satellite-Derived Bathymetry. Discov. Geosci. 2025, 3, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Akhoondzadeh, M. Mapping Water Salinity Using Landsat-8 OLI Satellite Images (Case Study: Karun Basin Located in Iran). Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 1490–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Akhoondzadeh, M. Generation of Karun River Water Salinity Map from Landsat-8 Satellite Images using Support Vector Regression, Multilayer Perceptron and Genetic Algorithm. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 46, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, D. Water Quality in the Fluvial Section Physicochemical and Bacteriological Parameters, 5th ed.; Canada Water Agency: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2023; ISBN 978-0-660-77291-2. [Google Scholar]

- EcoLogic LLC, St. Lawrence River Watershed Characterization Report; Franklin County Soil & Water Conservation District: Louisburg, NC, USA, 2019.

- Merriman, J. Water Quality in the St. Lawrence River at Wolfe Island; Environment Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 1997; ISBN 978978-1-100-17523-2. [Google Scholar]

- Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO). MERRA-2 tavg1_2d_aer_Nx: 2d,1-Hourly,Time-Averaged,Single-Level,Assimilation,Aerosol Diagnostics, V5.12.4; Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC): Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmel, T.; Chami, M.; Tormos, T.; Reynaud, N.; Danis, P.-A. Sunglint Correction of the Multi-Spectral Instrument (MSI)-SENTINEL-2 Imagery over Inland and Sea Waters from SWIR Bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OBPG. Ancillary Data. Available online: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/resources/docs/ancillary/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Knudby, A.; Richardson, G. Incorporation of Neighborhood Information Improves Performance of SDB Models. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 32, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 25 July 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, S.K.; Brito, T.V.; Welling, D.T. Measures of Model Performance Based On the Log Accuracy Ratio. Space Weather 2018, 16, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Overpass | Scene IDs |

|---|---|---|

| 2 August 2024 | L8, S2B | L8: LC08_L1TP_014028_20240802_20240808_02_T1 S2B: S2B_MSIL1C_20240802T154809_N0511_R054_T18TXR_20240802T192935 |

| 7 August 2024 | S2A | S2A_MSIL1C_20240807T154941_N0511_R054_T18TXR_20240807T211007 |

| 6 September 2024 | S2A | S2A_MSIL1C_20240906T154811_N0511_R054_T18TXR_20240906T210647 |

| 11 September 2024 | L9, S2B | L9: LC09_L1TP_014028_20240911_20240911_02_T1 S2B: S2B_MSIL1C_20240911T154809_N0511_R054_T18TXR_20240911T192755 |

| Sensor | Scenario | n_Estimators | Max_Depth | Learning_Rate | Feature_Fraction | Num_Leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L8/9 | No | 710 | 21 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 115 |

| AC | 962 | 14 | 0.004 | 0.12 | 102 | |

| AE | 594 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 27 | |

| S2 | No | 223 | 0 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 20 |

| AC | 259 | 49 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 5 | |

| AE | 362 | 37 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ansari, M.; Wu, Y.; Knudby, A. Assessing the Impact of T-Mart Adjacency Effect Correction on Turbidity Retrieval from Landsat 8/9 and Sentinel-2 Imagery (Case Study: St. Lawrence River, Canada). Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010127

Ansari M, Wu Y, Knudby A. Assessing the Impact of T-Mart Adjacency Effect Correction on Turbidity Retrieval from Landsat 8/9 and Sentinel-2 Imagery (Case Study: St. Lawrence River, Canada). Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010127

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnsari, Mohsen, Yulun Wu, and Anders Knudby. 2026. "Assessing the Impact of T-Mart Adjacency Effect Correction on Turbidity Retrieval from Landsat 8/9 and Sentinel-2 Imagery (Case Study: St. Lawrence River, Canada)" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010127

APA StyleAnsari, M., Wu, Y., & Knudby, A. (2026). Assessing the Impact of T-Mart Adjacency Effect Correction on Turbidity Retrieval from Landsat 8/9 and Sentinel-2 Imagery (Case Study: St. Lawrence River, Canada). Remote Sensing, 18(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010127