A Multi-Channel Convolutional Neural Network Model for Detecting Active Landslides Using Multi-Source Fusion Images

Highlights

- Based on multi-source fusion images, a new dataset and model were constructed for active landslide detection.

- The model introduces a Landslide Attention Module, which has a significant effect on improving the model’s performance in detecting active landslides.

- The proposed model achieves superior overall performance and generalization.

- Training with multi-source fusion images enhances performance and efficiency while reducing computation and parameters.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To develop a comprehensive dataset for active landslide detection by fusing optical remote sensing imagery, DEM- derived slope information, and InSAR-derived deformation data, with the goal of improving detection accuracy and reliability. The constructed dataset contains multi-source fusion images across multiple spatial scales, which enhances the model’s ability to generalize in detecting active landslides of diverse sizes.

- (2)

- To propose an active landslide detection model, namely MCLD R-CNN, which supports multi-channel data input and incorporates a Landslide Attention Module to fully exploit the characteristic features of active landslides embedded in the dataset.

- (3)

- To comprehensively assess how multi-source data influence model performance by contrasting the proposed method with traditional deep learning frameworks and various dataset types, and to further examine the strengths and weaknesses of the model regarding detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

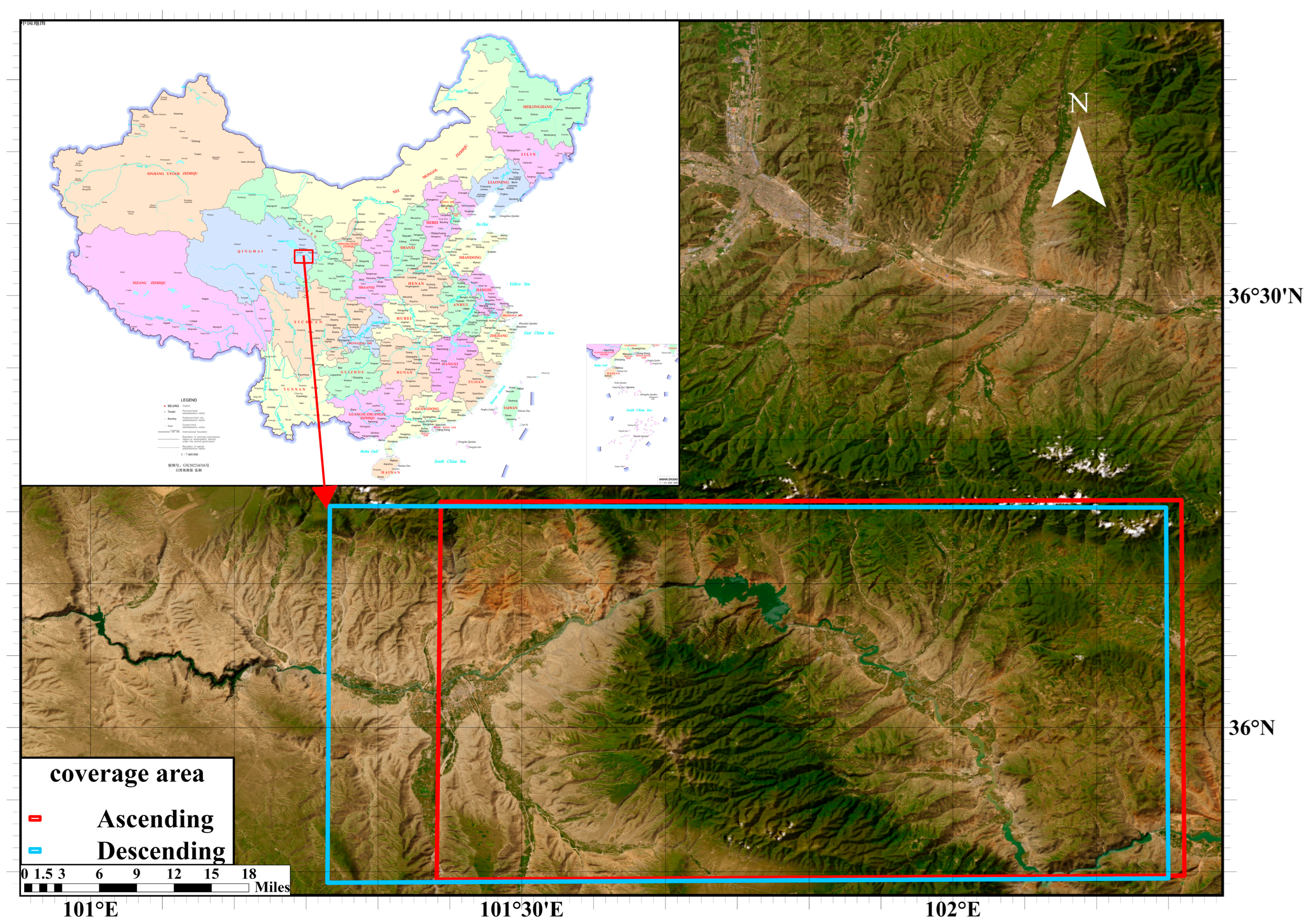

2. Research Area and Data Sources

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Data Sources

3. Method

3.1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing

3.1.1. Initial Data Processing

3.1.2. Multi-Source Data Fusion

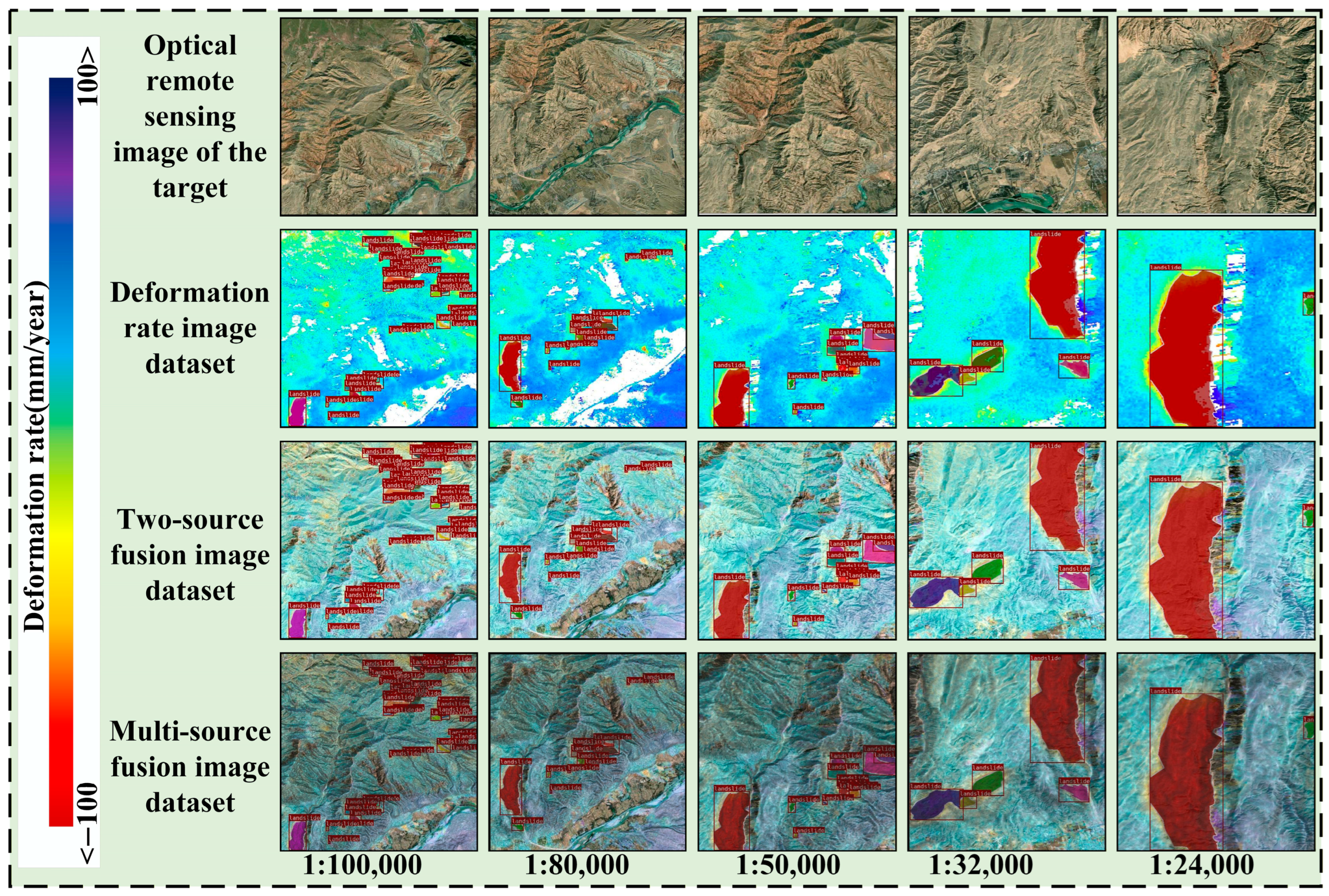

3.2. Dataset Creation

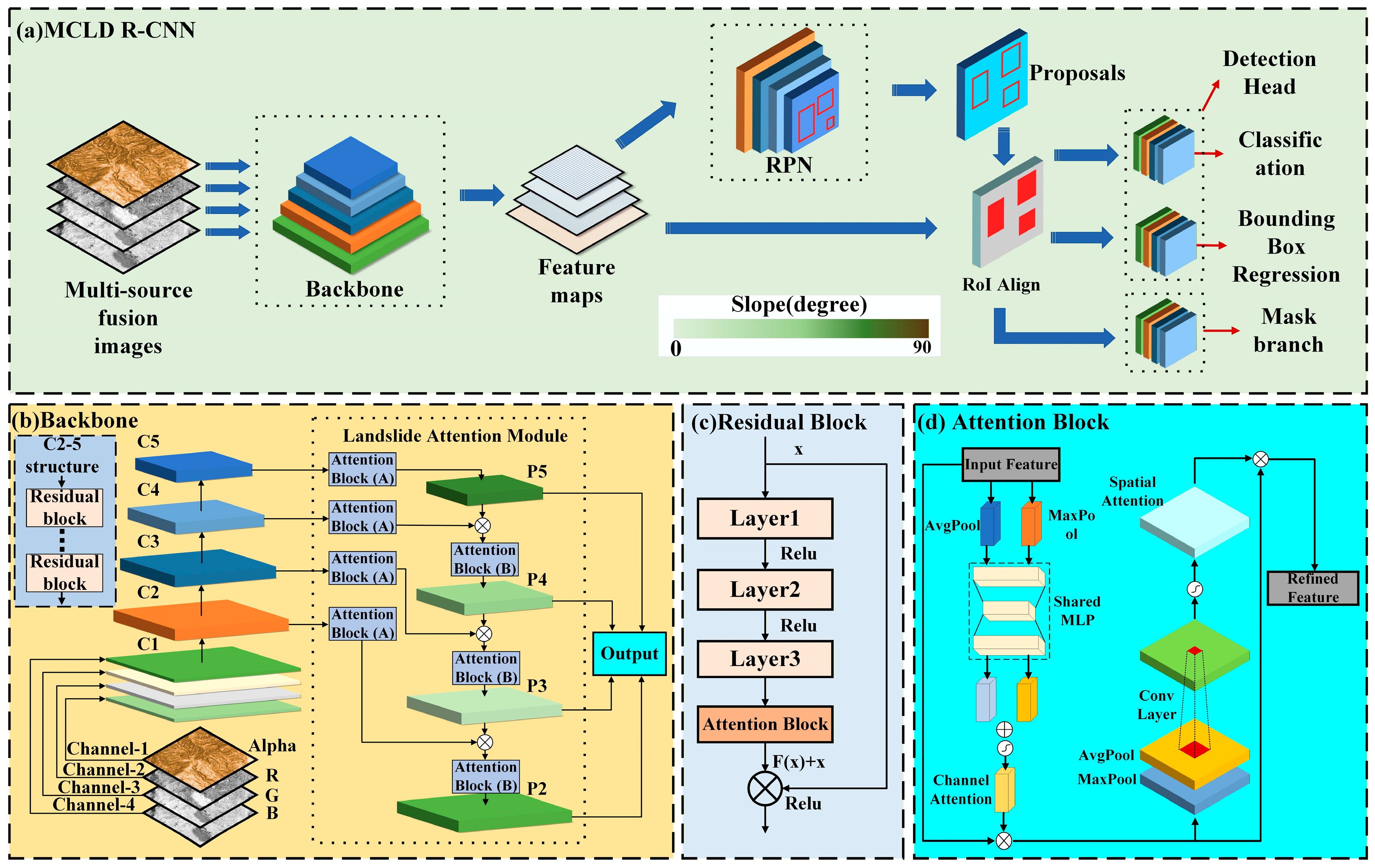

3.3. MCLD R-CNN

3.3.1. Backbone Network of MCLD R-CNN

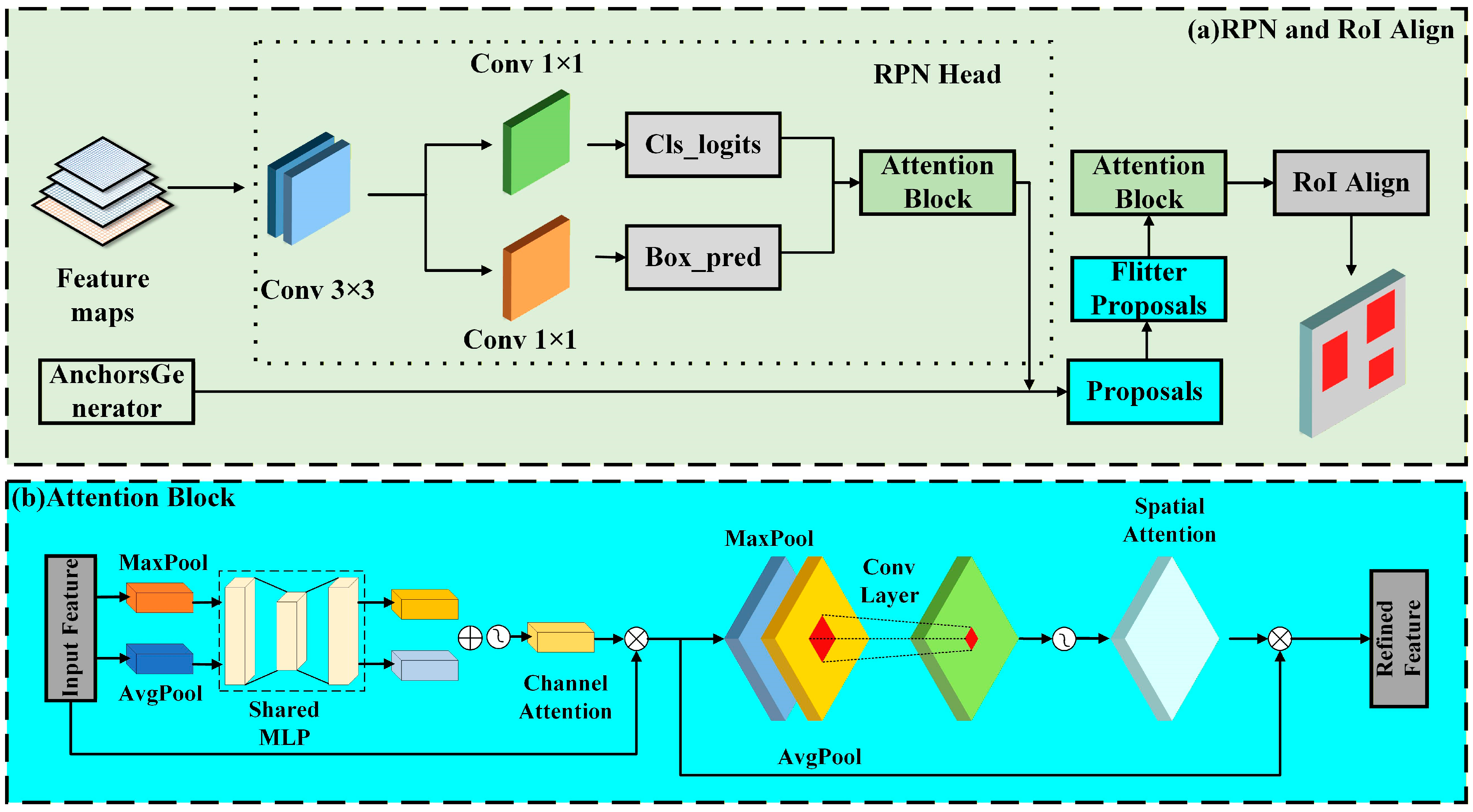

3.3.2. The Improved RPN and the RoI Align Layer

- (1)

- Multiple rectangular anchor boxes with varying scales and aspect ratios are predefined for each pixel in the input feature map. For the pixel located at (i, j) in the feature map, the center coordinates of its corresponding anchor boxes are defined as:

- (2)

- Through convolutional processing in the RPN head, the network outputs the objectness score for each anchor box and the bounding box offsets, which determine the candidate regions for subsequent processing. The RPN employs a joint loss function that includes both classification and regression components:

3.4. Model Performance Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Analysis of Experiments

4.1. Model Training Parameters

4.2. Model Performance Comparison

4.2.1. Comparison of Performance Evaluation Metrics

- (1)

- For the same model across different datasets, the models trained with multi-source fusion images consistently show the best performance, while the models trained with deformation rate image datasets perform inferiorly. This indicates that training the model with fusion images yields better results, and as the variety of fused data increases, the model’s performance improves progressively. This is particularly evident in the mAP50–95 metric, where the maximum improvements reached 45% (detection performance) and 60% (segmentation performance). Moreover, the Precision (detection performance) of our model improved from 93.95% on the deformation-only dataset to 97.79% on the multi-source dataset. This increase of nearly 4 percentage points signifies a substantial reduction in False Positives (FP), quantitatively confirming that fusing multi-source data effectively filters out confounding geological activities.

- (2)

- Across different models on the same dataset, MCLD R-CNN consistently demonstrates superior performance. Particularly in terms of R, F1, and mAP50 metrics, it achieved the highest detection and segmentation scores across all datasets. In some datasets, it also achieved the highest P score, and the mAP50–95 metric was only slightly lower than Yolov9. Therefore, based on these comparative results, it is evident that MCLD R-CNN offers the best overall performance.

- (1)

- In the deformation rate image dataset, all models showed varying levels of missed and false detections, which were particularly pronounced for small-scale images. This is primarily attributed to the relatively small spatial extent of most active landslides in these images, posing a challenge for the models to effectively extract features. The Yolov11 model exhibited the most severe detection errors, whereas MCLD R-CNN achieved an exceptionally low missed detection rate despite a few false positives. Segmentation performance across all models was generally poor, especially in large-scale images, where models struggled to outline complete landslide contours. This suggests that deformation rate features mainly assist in localization but are insufficient for determining precise coverage and contours.

- (2)

- In both the two-source and multi-source fusion image datasets, most models exhibited reduced missed and false detections, alongside significantly enhanced segmentation performance. Notably, models trained on multi-source fusion images demonstrated superior segmentation performance compared to those trained on two-source fusion image datasets. This indicates that multi-source imagery provides richer landslide-related features, thereby enhancing the model’s detection capability. However, it is notable that detection results for identical landslide instances were inconsistent across datasets. Specifically, models like Yolov8 and Yolov12 missed certain active landslides in the fusion images that they had correctly identified in other datasets. This phenomenon was primarily concentrated in small-scale images. A likely reason is that these models extract conflicting features from the fused images, rendering it difficult to distinguish whether a target is an active landslide. In summary, utilizing fusion imagery reduces detection errors, with the multi-source fusion image dataset yielding the most significant performance gains. The quantitative improvements shown in Table 3 effectively support this conclusion.

- (3)

- Across all datasets, our proposed model consistently maintained superior detection correctness and segmentation accuracy. This visual evidence directly demonstrates the performance advantages of our model, a finding further substantiated by the quantitative metrics analyzed above.

4.2.2. Model Training Curve Analysis

- (1)

- Within the same model, models trained with fusion images generally exhibit better performance and faster convergence. As the variety of fused data increases, the training results progressively improve. This is particularly evident in the Yolo series models. Therefore, using multi-source fused images for training significantly enhances training efficiency, enabling the model to attain improved performance with fewer training epochs.

- (2)

- Comparing Figure 11 with Table 3, it is clear that both MCLD R-CNN and Yolov9 models exhibit superior detection performance, but the former converges faster. Although Mask R-CNN has the fastest convergence speed, its detection performance is relatively weaker. Therefore, the model proposed in this study achieves a balance between convergence speed and detection performance. By leveraging multi-source fusion images, the training time of detection models can be reduced, thereby enhancing the efficiency of landslide detection.

4.3. Ablation Experiment

- (1)

- The visualization demonstrates that the attention module operates as a dual-functional filter. While it intensifies the feature response in target regions (indicated by “hot” red colors), it simultaneously suppresses activation in non-landslide regions (indicated by “cool” blue colors). The Sigmoid activation function within the module acts as a gate, assigning near-zero weights to complex background features such as rivers, vegetation, and stable slopes. This effectively “mutes” the interference from these areas, preventing them from being misclassified as foreground.

- (2)

- After removing the Landslide Attention Module, the model’s attention becomes randomly dispersed across the entire image, making it difficult to focus on the target. As a result, the model struggles to detect the landslide accurately and is more easily affected by irrelevant regions.

- (3)

- In certain cases, the model also focuses its attention on incorrect regions. For example, in the seventh sample image shown, the model concentrates on the river instead of the active landslide.

4.4. Evaluation of the Model’s Generalization Capability

- (1)

- MCLD R-CNN effectively detects most active landslides, demonstrating its high sensitivity to active landslides.

- (2)

- The Yolo series models exhibit a high number of missed detections, while Mask R-CNN exhibits poor segmentation performance. This indicates that these models struggle to adapt to unfamiliar images and can only achieve good performance on specific datasets.

- (3)

- The quantitative results presented on the right demonstrate that variations in landslide characteristics and data distribution relative to the training datasets led to decreased performance across all models. However, MCLD R-CNN still outperformed the others overall, with scores higher than the other models for all metrics except P.

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages and Limitations of the Dataset and Method

5.2. Model Advantages and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keefer, D.K.; Larsen, M.C. Assessing landslide hazards. Science 2007, 316, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froude, M.J.; Petley, D.N. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Li, Q.; Tian, N.; Peng, J. Remote Sensing Precursors Analysis for Giant Landslides. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, B.; Dai, K.; Dong, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; et al. Remote sensing for landslide investigations: A progress report from China. Eng. Geol. 2023, 321, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, M.; Cardinali, M.; Rossi, M.; Mondini, A.C.; Guzzetti, F. Remote landslide mapping using a laser rangefinder binocular and GPS. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 2539–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Mondini, A.C.; Cardinali, M.; Fiorucci, F.; Santangelo, M.; Chang, K.-T. Landslide inventory maps: New tools for an old problem. Earth Sci. Rev. 2012, 112, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneberg, W.C.; Cole, W.F.; Kasali, G. High-resolution lidar-based landslide hazard mapping and modeling, UCSF Parnassus Campus, San Francisco, USA. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2009, 68, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, C.; Stumpf, A.; Malet, J.-P.; Gancarski, P.; Puissant, A.; Passat, N. Hierarchical extraction of landslides from multiresolution remotely sensed optical images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 87, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesci, A.; Teza, G.; Casula, G.; Loddo, F.; De Martino, P.; Dolce, M.; Obrizzo, F.; Pingue, F. Multitemporal laser scanner-based observation of the Mt. Vesuvius crater: Characterization of overall geometry and recognition of landslide events. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massonnet, D.; Rossi, M.; Carmona, C.; Adragna, F.; Peltzer, G.; Feigl, K.; Rabaute, T. The displacement field of the Landers earthquake mapped by radar interferometry. Nature 1993, 364, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebker, H.A.; Villasenor, J. Decorrelation in interferometric radar echoes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Tang, Z.; Du, S.; Wang, P.; Fan, H.; Hao, M.; Tan, Z. Shadow-robust unsupervised flood mapping via GMM-enhanced generalized dual-polarization flood index and topography features. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 143, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Wang, P.; Hao, M.; Fan, H.; Tan, Z. Flood inundation mapping in SAR images based on nonlocal polarization combination features. J. Hydrol. 2025, 646, 132326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, L.; Bordoni, M.; Vivaldi, V.; Figini, S.; Parnigoni, M.; Grossi, A.; Lanteri, L.; Tararbra, M.; Negro, N.; Meisina, C. InterpolatiON of InSAR Time series for the dEtection of ground deforMatiOn eVEnts (ONtheMOVE): Application to slow-moving landslides. Landslides 2023, 20, 1797–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, P.A.; Hensley, S.; Joughin, I.R.; Li, F.K.; Madsen, S.N.; Rodriguez, E.; Goldstein, R.M. Synthetic aperture radar interferometry. Proc. IEEE 2000, 88, 333–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Cao, Y.; Gan, L.; Wang, Y.; Motagh, M.; Roessner, S.; Hu, X.; Yin, K. A novel framework for landslide displacement prediction using MT-InSAR and machine learning techniques. Eng. Geol. 2024, 334, 107497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dille, A.; Kervyn, F.; Handwerger, A.L.; d’Oreye, N.; Derauw, D.; Bibentyo, T.M.; Samsonov, S.; Malet, J.-P.; Kervyn, M.; Dewitte, O. When image correlation is needed: Unravelling the complex dynamics of a slow-moving landslide in the tropics with dense radar and optical time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Qu, W. Inferring slip-surface geometry and volume of creeping landslides based on InSAR: A case study in Jinsha River basin. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 294, 113620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauknes, T.R.; Piyush Shanker, A.; Dehls, J.F.; Zebker, H.A.; Henderson, I.H.C.; Larsen, Y. Detailed rockslide mapping in northern Norway with small baseline and persistent scatterer interferometric SAR time series methods. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2097–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Motagh, M.; Mirzaee, S.; Li, T.; Zhou, C.; Tang, H.; Roessner, S. The 21 July 2020 Shaziba landslide in China: Results from multi-source satellite remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Mei, G. Deep learning for geological hazards analysis: Data, models, applications, and opportunities. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 223, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Yao, S.; Ye, C. A universal adapter in segmentation models for transferable landslide mapping. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, W. A dual-encoder U-Net for landslide detection using Sentinel-2 and DEM data. Landslides 2023, 20, 1975–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Li, W.; Yu, J.; Ge, D.; Han, L.; Xiang, W. An Iterative Classification and Semantic Segmentation Network for Old Landslide Detection Using High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4408813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Bai, S.; Kong, L. A review on 2D instance segmentation based on deep neural networks. Image Vis. Comput. 2022, 120, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Ma, L.; Li, Q.; Du, F. ShapeFormer: A Shape-Enhanced Vision Transformer Model for Optical Remote Sensing Image Landslide Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullo, S.L.; Mohan, A.; Sebastianelli, A.; Ahamed, S.E.; Kumar, B.; Dwivedi, R.; Sinha, G.R. A New Mask R-CNN-Based Method for Improved Landslide Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 3799–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, L.; Dong, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Liao, M. Automatic identification of active landslides over wide areas from time-series InSAR measurements using Faster RCNN. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yi, B.; Yao, Q.; Gao, P.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Zhong, C. Identification of Landslides in Mountainous Area with the Combination of SBAS-InSAR and Yolo Model. Sensors 2022, 22, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Cao, D.; Yi, Y.; Wu, X. A New Deep Learning Neural Network Model for the Identification of InSAR Anomalous Deformation Areas. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 833–851. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yao, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yao, C.; Ren, K. DRs-UNet: A Deep Semantic Segmentation Network for the Recognition of Active Landslides from InSAR Imagery in the Three Rivers Region of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Xi, J.; Khan, B.A. An Embedding Swin Transformer Model for Automatic Slow-Moving Landslide Detection Based on InSAR Products. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5223915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, J. A Multi-Input Channel U-Net Landslide Detection Method Fusing SAR Multisource Remote Sensing Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 17, 1215–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, X.; Li, W. Mechanism of Giant Landslides from Longyangxia Valley to Liujiaxia Valley along Upper Yellow River. J. Eng. Geol. 2011, 19, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Li, Z.; Song, C.; Zhu, W.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, B.; Su, S. InSAR-Based Active Landslide Detection and Characterization Along the Upper Reaches of the Yellow River. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 3819–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Lan, H.; Qian, H.; Wang, W.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, S. Scientific Research Framework of Livable Yellow River. J. Eng. Geol. 2020, 28, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Cheng, G.; Hu, G.; Wei, G.; Wang, Y. Preliminary Study on Characteristic and Mechanism of Super-Large Landslides in Upper Yellow River Since Late-Pleistocene. J. Eng. Geol. 2010, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Qin, X.; Zhao, W. Characteristics of Landslides from Sigou Gorge to Lagan Gorge in the Upper Reaches of Yellow River. In Proceedings of the Third World Landslide Forum, Beijing, China, 2–6 June 2014; pp. 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Berardino, P.; Fornaro, G.; Lanari, R.; Sansosti, E. A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmller, U.; Strozzi, T.; Wiesmann, A. GAMMA SAR and interferometric processing software. In Proceedings of the ERS-Envisat Symposium, Gothenburg, Sweden, 16–20 October 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, F.; Lv, X.; Dou, F.; Yun, Y. A Review of Time-Series Interferometric SAR Techniques: A Tutorial for Surface Deformation Analysis. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2020, 8, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A. A multi-temporal InSAR method incorporating both persistent scatterer and small baseline approaches. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L16302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X.; Zhao, F.; Liang, Y.; Meng, X.; Jia, J. Early identification and characteristics of potential landslides in the Bailong River Basin using InSAR technique. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 25, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, B.; He, X.; Zhao, Z. An identification method of potential landslide zones using InSAR data and landslide susceptibility. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2185120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Brabandere, B.D.; Neven, D.; Gool, L.V. Semantic Instance Segmentation with a Discriminative Loss Function. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, B.; Arbeláez, P.; Girshick, R.; Malik, J. Simultaneous Detection and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 936–944. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; M., S. YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS), Chennai, India, 18–19 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Mark Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Beam Modes | Polarizations | Flight Directions | Path | Frame | Number of Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IW | VV + VH | ASCENDING | 128 | 114 | 45 |

| IW | VV + VH | DESCENDING | 33 | 472 | 63 |

| IW | VV + VH | DESCENDING | 135 | 473 | 57 |

| Model | Epoch | Learning-Rate | Batch Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov8 [56] | 1000 | 0.001 | 8 |

| Yolov9 [57] | 1000 | 0.001 | 8 |

| Yolov11 [58] | 1000 | 0.001 | 8 |

| Yolov12 [59] | 1000 | 0.001 | 8 |

| Mask R-CNN-50 [49] | 40 | 0.02 | 8 |

| Mask R-CNN-101 | 40 | 0.02 | 8 |

| Mask R-CNN-152 | 40 | 0.02 | 8 |

| Dataset | Model | Detection Performance | Segmentation Performance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | R | F1 | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | P | R | F1 | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | ||

| Defor mation rate image dataset | Yolov8 | 81.40 | 64.00 | 71.66 | 73.60 | 44.00 | 79.80 | 59.20 | 67.97 | 69.10 | 32.30 |

| Yolov9 | 94.60 | 87.00 | 90.64 | 93.30 | 72.80 | 93.50 | 82.60 | 87.71 | 90.20 | 57.50 | |

| Yolov11 | 85.10 | 67.80 | 75.47 | 77.00 | 48.60 | 83.50 | 63.80 | 72.33 | 73.00 | 36.50 | |

| Yo1ov12 | 85.50 | 67.40 | 75.38 | 77.40 | 50.10 | 85.10 | 65.60 | 74.09 | 75.10 | 38.70 | |

| Maskrcnn-50 | 73.74 | 78.96 | 76.26 | 78.16 | 54.27 | 66.14 | 71.52 | 68.73 | 70.69 | 37.58 | |

| Maskrcnn-101 | 75.46 | 79.67 | 77.51 | 79.24 | 55.31 | 67.46 | 72.53 | 69.90 | 72.20 | 38.39 | |

| Maskrcnn-152 | 76.65 | 80.83 | 78.68 | 80.12 | 56.15 | 67.44 | 72.96 | 70.09 | 73.15 | 38.94 | |

| Our model | 93.95 | 95.93 | 94.93 | 95.00 | 61.86 | 87.06 | 89.98 | 88.50 | 91.25 | 45.18 | |

| Two- source fusion image dataset | Yolov8 | 84.60 | 66.10 | 74.21 | 76.80 | 46.70 | 85.50 | 64.40 | 73.46 | 75.10 | 39.10 |

| Yolov9 | 96.10 | 90.10 | 93.00 | 95.10 | 78.30 | 93.60 | 87.20 | 90.29 | 93.10 | 63.20 | |

| Yolov11 | 83.10 | 72.10 | 77.21 | 80.50 | 52.70 | 85.40 | 68.10 | 75.78 | 78.50 | 43.30 | |

| Yolov12 | 88.50 | 70.90 | 78.73 | 81.81 | 54.50 | 87.80 | 69.40 | 77.52 | 80.40 | 45.60 | |

| Maskrcnn-50 | 81.04 | 84.71 | 82.83 | 84.29 | 59.31 | 76.73 | 80.63 | 78.63 | 80.33 | 45.79 | |

| Maskrcnn-101 | 81.92 | 85.71 | 83.78 | 85.34 | 60.00 | 78.73 | 82.50 | 80.57 | 82.06 | 46.93 | |

| Maskrcnn-152 | 82.90 | 86.39 | 84.60 | 84.99 | 60.60 | 78.24 | 82.22 | 80.18 | 81.19 | 46.65 | |

| Our model | 96.66 | 97.60 | 97.13 | 97.50 | 71.23 | 93.34 | 94.82 | 94.08 | 95.45 | 56.75 | |

| Multi-source fusion image dataset | Yolov8 | 92.80 | 82.30 | 87.24 | 90.60 | 64.00 | 92.80 | 77.30 | 84.34 | 87.70 | 51.80 |

| Yolov9 | 97.20 | 95.70 | 96.44 | 97.20 | 86.80 | 95.00 | 90.20 | 92.54 | 95.50 | 70.10 | |

| Yolov11 | 89.90 | 79.30 | 84.27 | 87.60 | 60.20 | 89.20 | 76.70 | 82.48 | 85.70 | 49.80 | |

| Yolov12 | 91.30 | 77.50 | 83.84 | 87.40 | 60.20 | 91.50 | 74.20 | 81.95 | 85.10 | 49.00 | |

| Maskrcnn-50 | 83.08 | 85.67 | 84.35 | 86.10 | 60.10 | 78.63 | 81.54 | 80.06 | 82.10 | 47.20 | |

| Maskrcnn-101 | 84.51 | 87.78 | 86.11 | 87.30 | 60.40 | 79.84 | 83.03 | 81.40 | 83.50 | 46.80 | |

| Maskrcnn-152 | 83.01 | 86.00 | 84.48 | 86.00 | 60.20 | 78.01 | 81.45 | 79.69 | 82.50 | 47.20 | |

| Our model | 97.79 | 98.18 | 97.98 | 97.88 | 75.48 | 95.70 | 96.55 | 96.12 | 96.73 | 60.95 | |

| Index | Att | Layers | Par | FLOPs | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Det | No | 50 | 43.98 M | 129.46 G | 96.48 | 97.60 | 97.26 | 68.94 | 97.03 |

| Yes | 50 | 46.51 M | 201.97 G | 97.79 | 98.18 | 97.88 | 75.48 | 97.98 | |

| Seg | No | 50 | 43.98 M | 129.46 G | 92.35 | 93.82 | 94.52 | 54.99 | 93.07 |

| Yes | 50 | 46.51 M | 201.97 G | 95.70 | 96.55 | 96.73 | 60.95 | 96.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Fan, H.; Tuo, W.; Ren, Y. A Multi-Channel Convolutional Neural Network Model for Detecting Active Landslides Using Multi-Source Fusion Images. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010126

Wang J, Fan H, Tuo W, Ren Y. A Multi-Channel Convolutional Neural Network Model for Detecting Active Landslides Using Multi-Source Fusion Images. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jun, Hongdong Fan, Wanbing Tuo, and Yiru Ren. 2026. "A Multi-Channel Convolutional Neural Network Model for Detecting Active Landslides Using Multi-Source Fusion Images" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010126

APA StyleWang, J., Fan, H., Tuo, W., & Ren, Y. (2026). A Multi-Channel Convolutional Neural Network Model for Detecting Active Landslides Using Multi-Source Fusion Images. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010126