Fusion of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Images for Producing Daily Maps of Advected Aerosols at Urban Scale

Highlights

- Calculate dense maps of Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) from Sentinel-2/3 images.

- Discriminate the type of AOD, either coarse or fine, from its scattering properties.

- The maps produced from S2 and S3 data are merged to achieve a spatio-temporal fusion.

- The method does not require the availability of ground-based auxiliary data.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

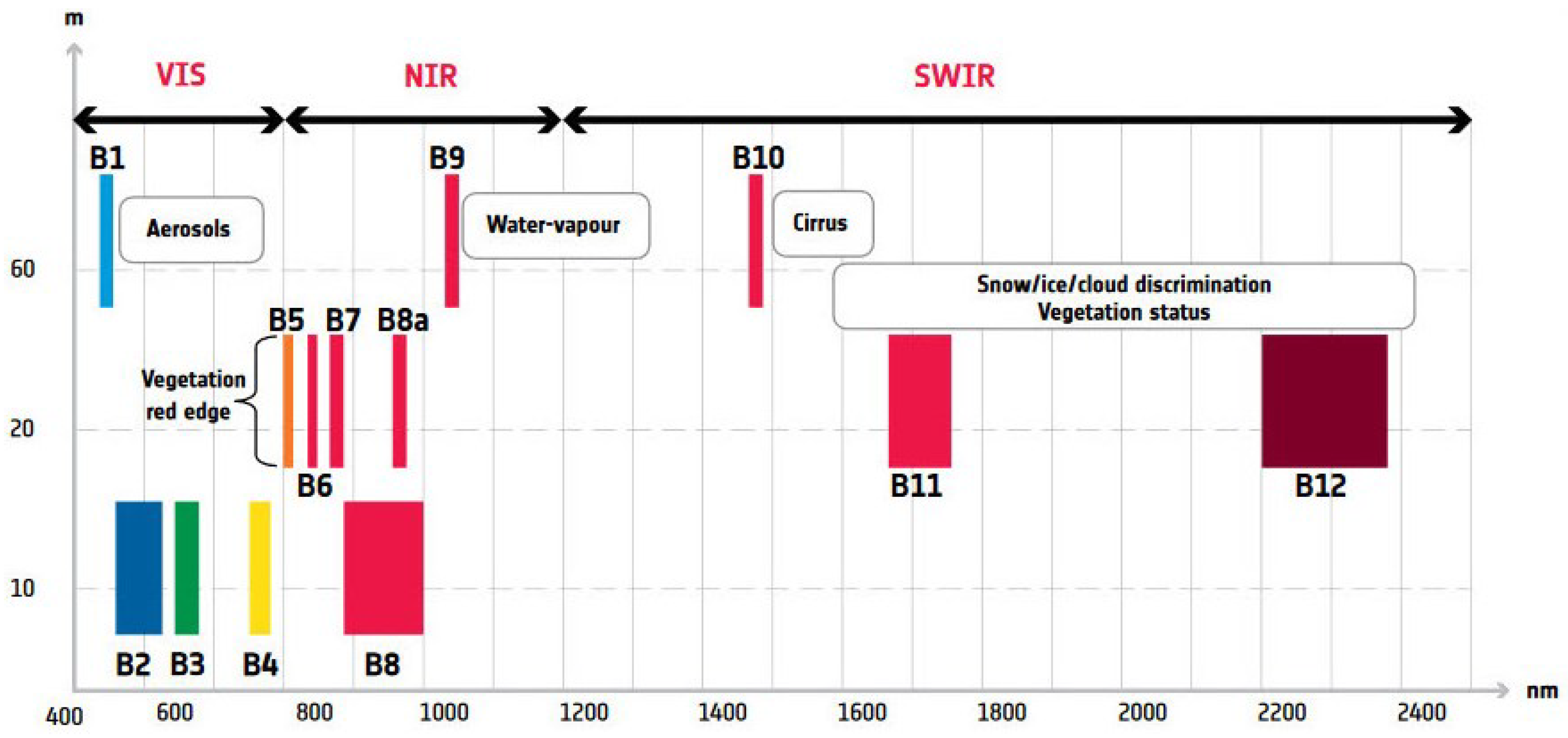

2.1. Sentinel-2 MSI

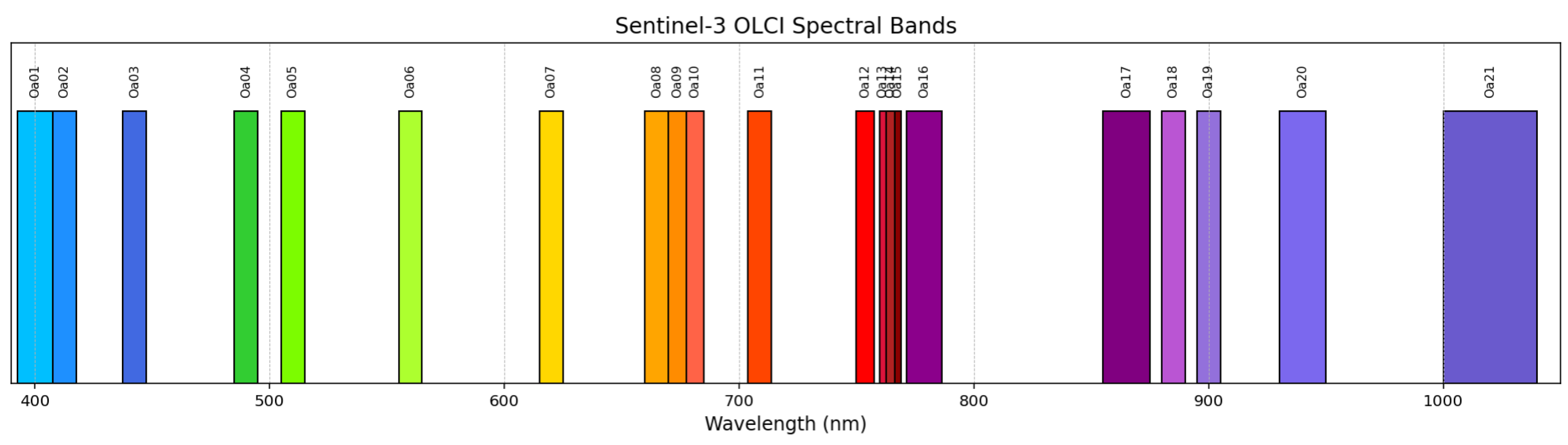

2.2. Sentinel-3 OLCI

2.3. AERONET

2.4. Aerosol Spatial Index

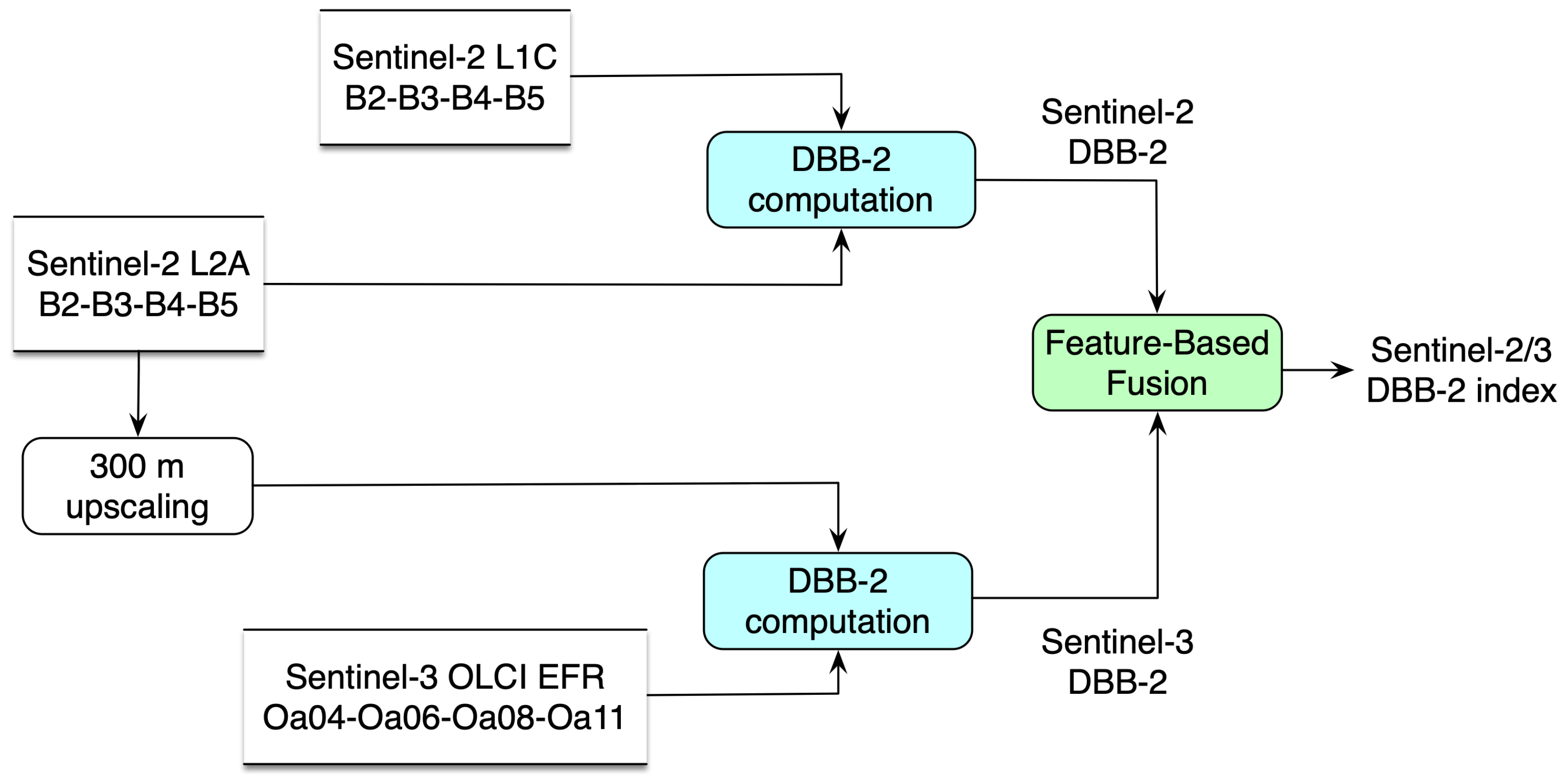

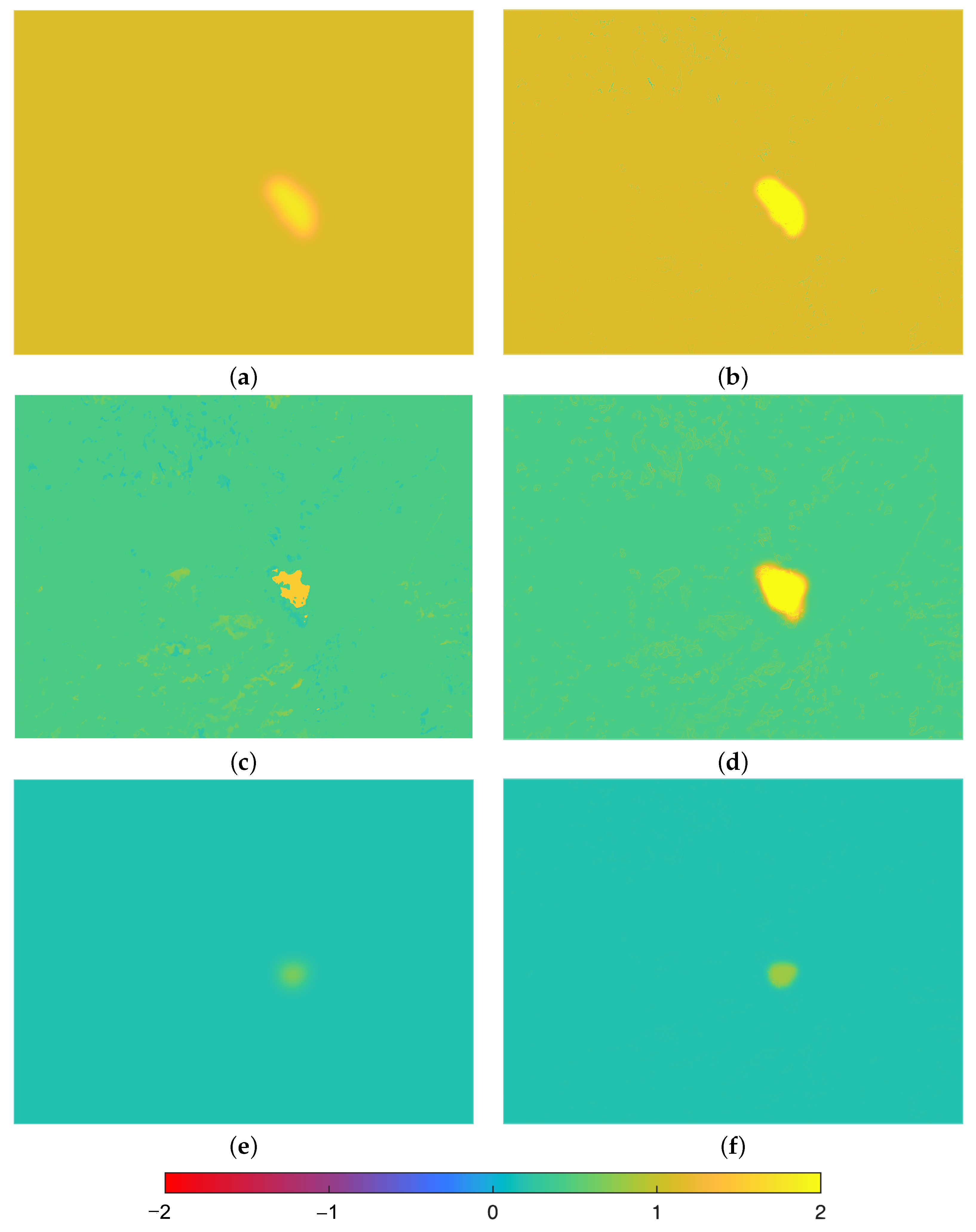

2.5. Data Fusion

3. Results

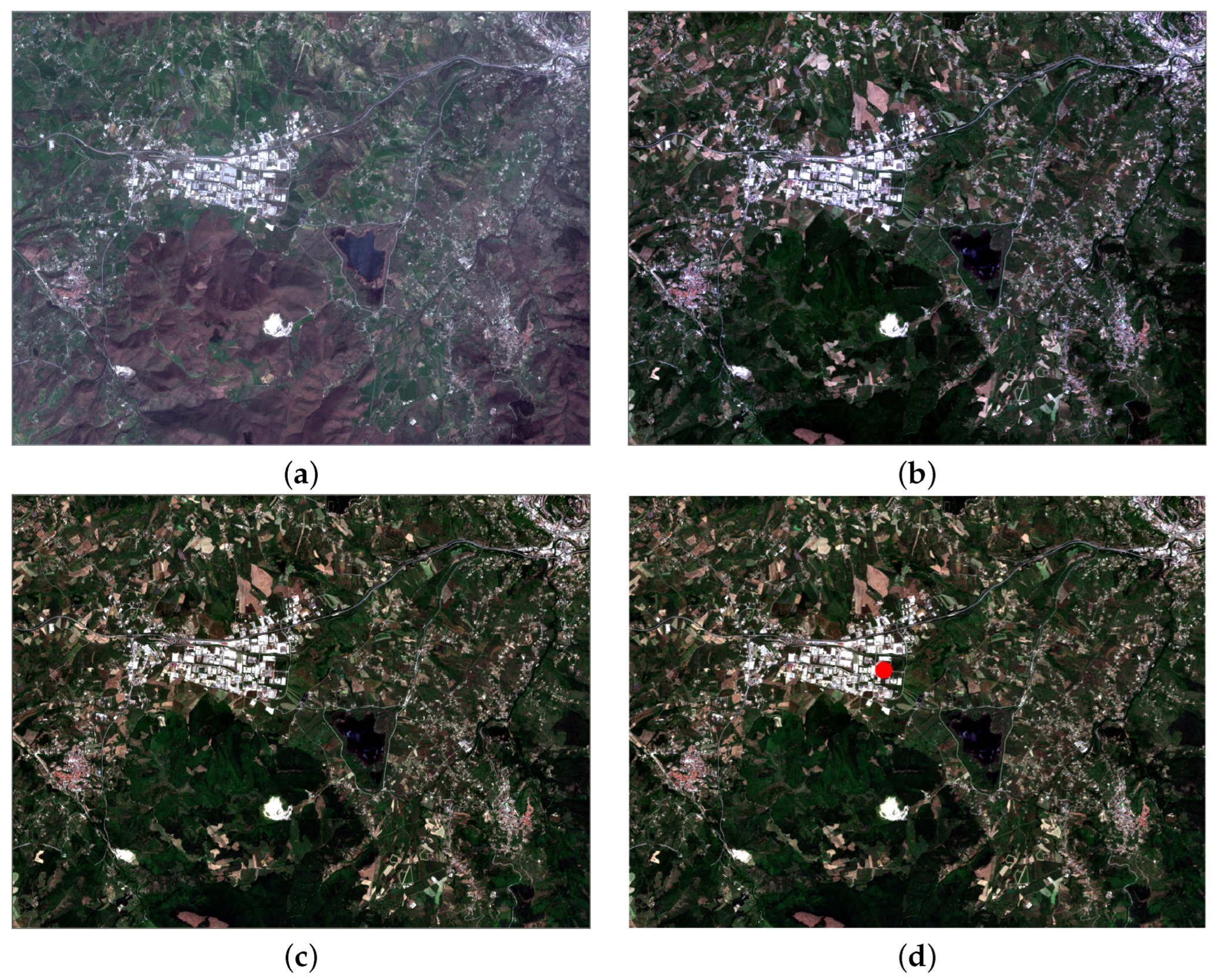

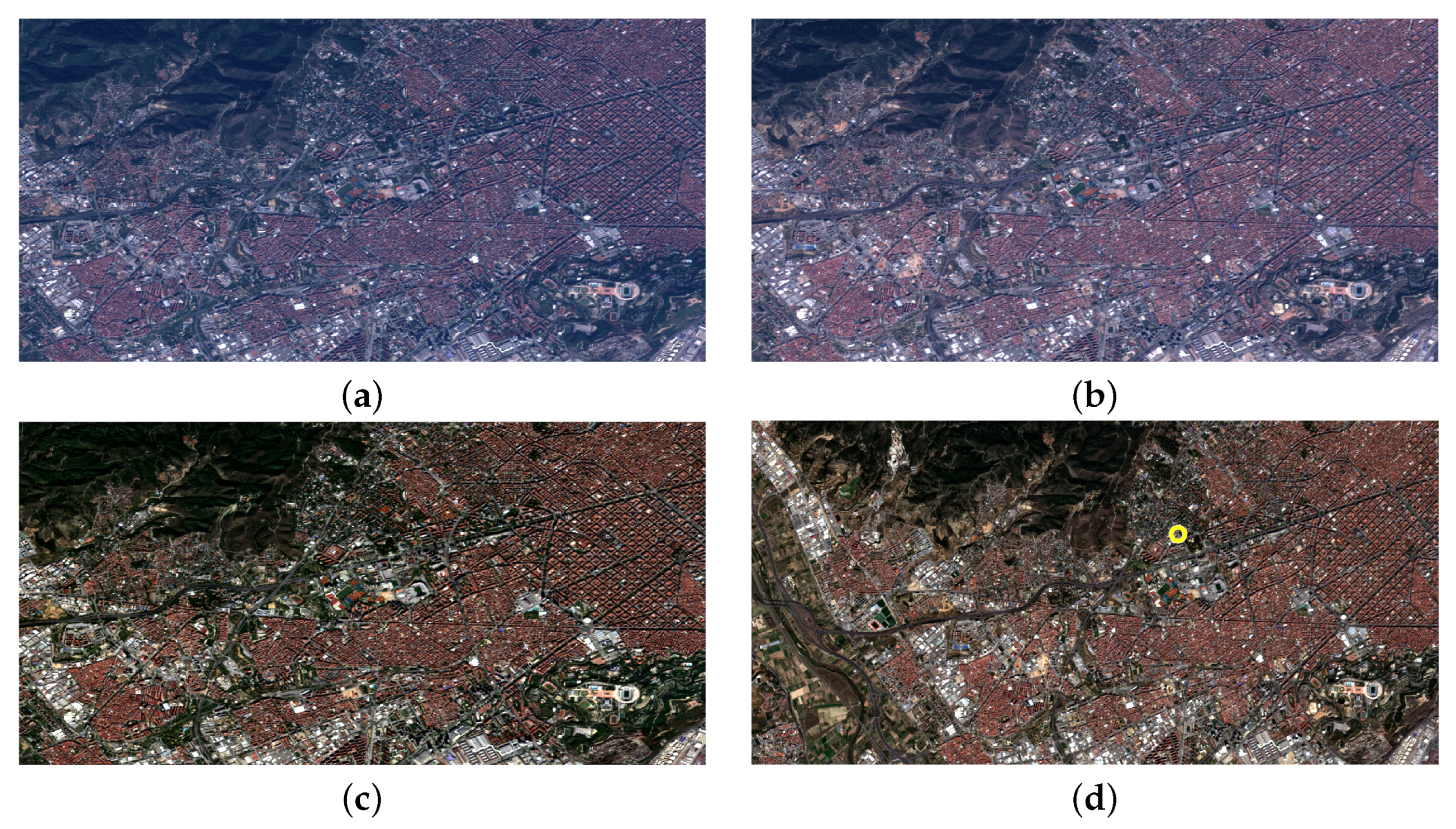

3.1. Dust Outbreak Event

3.2. Biomass Burning Event

3.3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baltensperger, U.; Prévôt, A. Chemical analysis of atmospheric aerosols. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 390, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Milroy, C.; Martucci, G.; Lolli, S.; Loaec, S.; Sauvage, L.; Xueref-Remy, I.; Lavrič, J.; Ciais, P.; Feist, D.; Biavati, G.; et al. An assessment of pseudo-operational ground-based light detection and ranging sensors to determine the boundary-layer structure in the coastal atmosphere. Adv. Meteorol. 2012, 2012, 929080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Tang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zou, Z.; Li, T.; Peng, C. Research progress, challenges, and prospects of PM2.5 concentration estimation using satellite data. Environ. Rev. 2023, 31, 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.; Lohmann, U.; Raga, G.; O’Dowd, C.; Kulmala, M.; Fuzzi, S.; Reissell, A.; Andreae, M. Flood or drought: How do aerosols affect precipitation? Science 2008, 321, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Díaz, C.; Sicard, M.; Nabat, P.; Mallet, M.; Muñoz-Porcar, C.; Comerón, A.; Rodríguez-Gómez, A.; Dos Santos Oliveira, D.C.F. Dust aerosol radiative effects during a dust event and heatwave in summer 2019 simulated with a regional climate atmospheric model over the Iberian peninsula. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Kumar, M.; Singh, N. Aerosol, climate, and sustainability. In Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, T.C.; Bonasoni, P.; Brunetti, M.; Campbell, J.R.; Marquis, J.W.; Di Girolamo, P.; Lolli, S. Aerosol direct radiative effects under cloud-free conditions over highly-polluted areas in Europe and Mediterranean: A ten-years analysis (2007–2016). Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Nichol, J.; Nazeer, M.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Kumar, K.; Ho, H.C.; Mazhar, U.; Bleiweiss, M.; Qiu, Z.; et al. Characteristics of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) over urban, suburban, and rural areas of Hong Kong. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.C.; King, A.D.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Mitchell, D.M. Regional hotspots of temperature extremes under 1.5 °C and 2 °C of global mean warming. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2019, 26, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegl, T.; Langematz, U. Twenty-first-century climate change hot spots in the light of a weakening sun. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 3431–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, S.; Khor, W.Y.; Matjafri, M.Z.; Lim, H.S. Monsoon season quantitative assessment of biomass burning clear-sky aerosol radiative effect at surface by ground-based Lidar observations in Pulau Pinang, Malaysia in 2014. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, M.; Mukai, S.; Fujito, T. Direct detection of severe biomass burning aerosols from satellite data. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopp, L.; Wieland, M.; Rättich, M.; Martinis, S. A deep learning approach for burned area segmentation with Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, J.S.; Manchanda, C. High-resolution urban air pollution mapping. Science 2024, 385, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolli, S.; Alparone, L.; Arienzo, A.; Garzelli, A. Characterizing dust and biomass burning events from Sentinel-2 imagery. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, S. Urban PM2.5 concentration monitoring: A review of recent advances in ground-based, satellite, model, and machine learning integration. Urban Clim. 2025, 63, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qin, K.; Xu, J.; Yuan, L.; Li, D.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, K. Aerosol vertical distribution and sources estimation at a site of the Yangtze River Delta region of China. Atmos. Res. 2019, 217, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; He, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cohen, J.B.; Tiwari, P.; Lolli, S. Aloft transport of haze aerosols to Xuzhou, Eastern China: Optical properties, sources, type, and components. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, S.; Sicard, M.; Amato, F.; Comeron, A.; Gíl-Diaz, C.; Landi, T.C.; Munoz-Porcar, C.; Oliveira, D.; Dios Otin, F.; Rocadenbosch, F.; et al. Climatological assessment of the vertically resolved optical and microphysical aerosol properties by Lidar measurements, sun photometer, and in situ observations over 17 years at Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) Barcelona. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 12887–12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.J.; Hao, X.; Kafatos, M.; Wang, L. Asian dust storm monitoring combining Terra and Aqua MODIS SRB measurements. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2006, 3, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Oliveira, D.C.F.; Sicard, M.; Rodríguez-Gómez, A.; Comerón, A.; Muñoz-Porcar, C.; Gil-Díaz, C.; Dubovik, O.; Derimian, Y.; Momoi, M.; Lopatin, A. Aerosol forcing from ground-based synergies over a decade in Barcelona, Spain. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M.; Malavelle, F.; Adam, M.; Buxmann, J.; Sugier, J.; Marenco, F.; Haywood, J. Saharan dust and biomass burning aerosols during ex-hurricane Ophelia: Observations from the new UK Lidar and sun-photometer network. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 3557–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Fan, M.; Tao, J. An improved method for retrieving Aerosol Optical Depth using Gaofen-1 WFV camera data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgenieva, T.S.; Gurdev, L.; Toncheva, E.; Dreischuh, T. Aerosol types identification during different aerosol events over Sofia, Bulgaria, using sun-photometer and satellite data on the aerosol optical depth and Ångström exponent. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2240, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulenkov, D.A.; Sapunov, M.V. The aerosol pollution of the atmosphere on the example of Lidar sensing data in St. Petersburg (Russia), Kuopio (Finland), Minsk (Belarus). Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 16, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivone, G.; Arienzo, A.; Bilal, M.; Garzelli, A.; Pappalardo, G.; Lolli, S. A dark target Kalman filter algorithm for aerosol property retrievals in urban environment using multispectral images. Urban Clim. 2022, 43, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustin, S.L.; Middleton, E.M. Current and near-term advances in Earth observation for ecological applications. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparone, L.; Aiazzi, B.; Baronti, S.; Garzelli, A. Remote Sensing Image Fusion; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alparone, L.; Arienzo, A.; Garzelli, A. Spatial resolution enhancement of satellite hyperspectral data via nested hypersharpening with Sentinel-2 multispectral data. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10956–10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main-Knorn, M.; Pflug, B.; Louis, J.; Debaecker, V.; Müller-Wilm, U.; Gascon, F. Sen2Cor for Sentinel-2. In Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXIII; Bruzzone, L., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Proceedings of SPIE; Volume 10427, p. 1042704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, F.; Longbotham, N.; Emery, W.J. The importance of physical quantities for the analysis of multitemporal and multiangular optical very high spatial resolution images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 6241–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holben, B.N.; Eck, T.F.; Slutsker, I.; Tanre, D.; Buis, J.P.; Setzer, A.; Vermote, E.; Reagan, J.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Nakajima, T.; et al. AERONET—A federated instrument network and data archive for aerosol characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 66, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, N.; Eck, T.; Smirnov, A.; Holben, B.; Thulasiraman, S. Spectral discrimination of coarse and fine mode optical depth. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, AAC 8-1–AAC 8-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arola, A.; Eck, T.; Kokkola, H.; Pitkänen, M.; Romakkaniemi, S. Assessment of cloud related fine mode AOD enhancements based on AERONET SDA product. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 17, 5991–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Dubovik, O.; Fuertes, D.; Schuster, G.; Cachorro, V.; Lapyonok, T.; Goloub, P.; Blarel, L.; Barreto, A.; Mallet, M.; et al. Advanced characterisation of aerosol size properties from measurements of spectral optical depth using the GRASP algorithm. Atmos. Measur. Tech. 2016, 10, 3743–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, D.M.; Sinyuk, A.; Sorokin, M.G.; Schafer, J.S.; Smirnov, A.; Slutsker, I.; Eck, T.F.; Holben, B.N.; Lewis, J.R.; Campbell, J.R.; et al. Advancements in the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) Version 3 database–automated near-real-time quality control algorithm with improved cloud screening for Sun photometer aerosol optical depth (AOD) measurements. Atmos. Measur. Tech. 2019, 12, 169–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jing, L. Improvement of a pansharpening method taking into account haze. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 5039–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapini, A.; Bianchi, T.; Argenti, F.; Alparone, L. Blind speckle decorrelation for SAR image despeckling. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparone, L.; Garzelli, A.; Zoppetti, C. Fusion of VNIR optical and C-band polarimetric SAR satellite data for accurate detection of temporal changes in vegetated areas. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiazzi, B.; Alparone, L.; Baronti, S.; Garzelli, A.; Selva, M. Advantages of Laplacian pyramids over “à trous” wavelet transforms for pansharpening of multispectral images. In Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XVIII; Bruzzone, L., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; Volume 8537, pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparone, L.; Garzelli, A.; Vivone, G. Spatial consistency for full-scale assessment of pansharpening. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Geoscience And Remote Sensing Symposium, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 5132–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, B.; Mytilinaios, M.; Amodeo, A.; Colangelo, C.; D’Amico, G.; Dema, C.; Gandolfi, I.; Giunta, A.; Gumà-Claramunt, P.; Laurita, T.; et al. Observations of Saharan dust intrusions over Potenza, Southern Italy, during 13 years of Lidar measurements: Seasonal variability of optical properties and radiative impact. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, M.; Granados-Muñoz, M.; Alados-Arboledas, L.; Barragán, R.; Bedoya-Velásquez, A.; Benavent-Oltra, J.; Bortoli, D.; Comerón, A.; Córdoba-Jabonero, C.; Costa, M.; et al. Ground/space, passive/active remote sensing observations coupled with particle dispersion modelling to understand the inter-continental transport of wildfire smoke plumes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

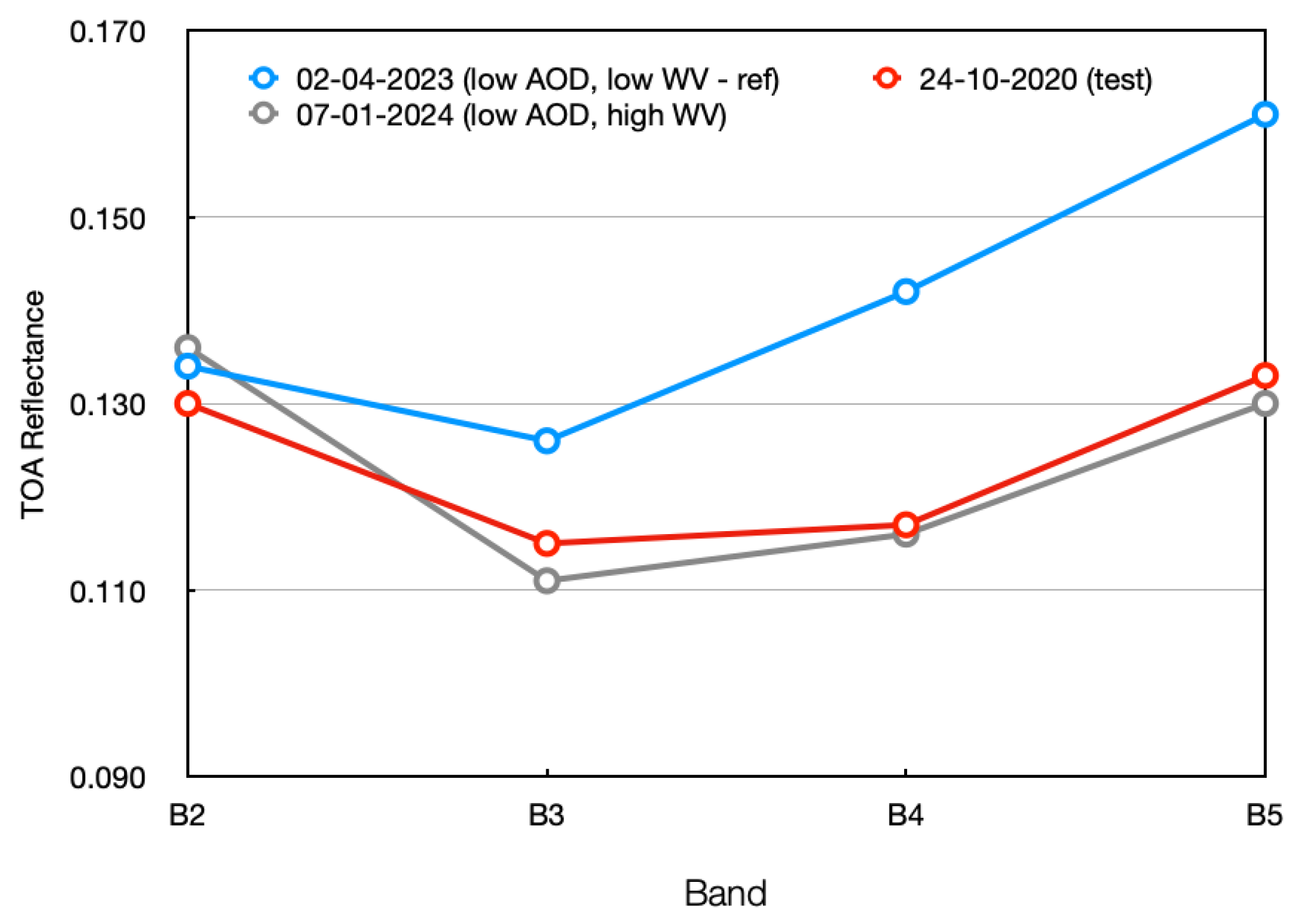

| AERONET AOD | DBB-2 (S2) | DBB-2 (OLCI + S2) | DBB-2 (OLCI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 March 2024 | 1.01 | - | 1.111 | 1.110 |

| 1 April 2024 | 0.40 | 0.408 | 0.406 | 0.404 |

| 7 April 2024 | 0.07 | - | 0.083 | 0.083 |

| 5 June 2024 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AERONET AOD | DBB-2 (S2) | DBB-2 (OLCI + S2) | DBB-2 (OLCI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 October 2020 | 0.089 | −0.092 | −0.091 | −0.092 |

| 28 October 2020 | 0.053 | - | −0.060 | −0.060 |

| 2 April 2023 | 0.029 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alparone, L.; Bianchini, M.; Garzelli, A.; Lolli, S. Fusion of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Images for Producing Daily Maps of Advected Aerosols at Urban Scale. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010116

Alparone L, Bianchini M, Garzelli A, Lolli S. Fusion of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Images for Producing Daily Maps of Advected Aerosols at Urban Scale. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlparone, Luciano, Massimo Bianchini, Andrea Garzelli, and Simone Lolli. 2026. "Fusion of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Images for Producing Daily Maps of Advected Aerosols at Urban Scale" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010116

APA StyleAlparone, L., Bianchini, M., Garzelli, A., & Lolli, S. (2026). Fusion of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3 Images for Producing Daily Maps of Advected Aerosols at Urban Scale. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010116