A Deep Learning Approach to Lidar Signal Denoising and Atmospheric Feature Detection

Highlights

- A deep learning-based denoising algorithm using U-Net CNNs significantly improves the signal-to-noise ratio of ICESat-2 daytime lidar data.

- The method enables accurate daytime cloud–aerosol discrimination and layer detection at native spatial resolution.

- The approach allows fast processing of photon-counting lidar data, enhancing the utility of daytime observations and improving sensitivity to optically thin atmospheric features.

- This methodology supports the development of smaller, lower-power spaceborne lidar systems capable of delivering high-quality atmospheric data products comparable to larger instruments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Description

2.1. ICESat-2 Atmospheric Data Products

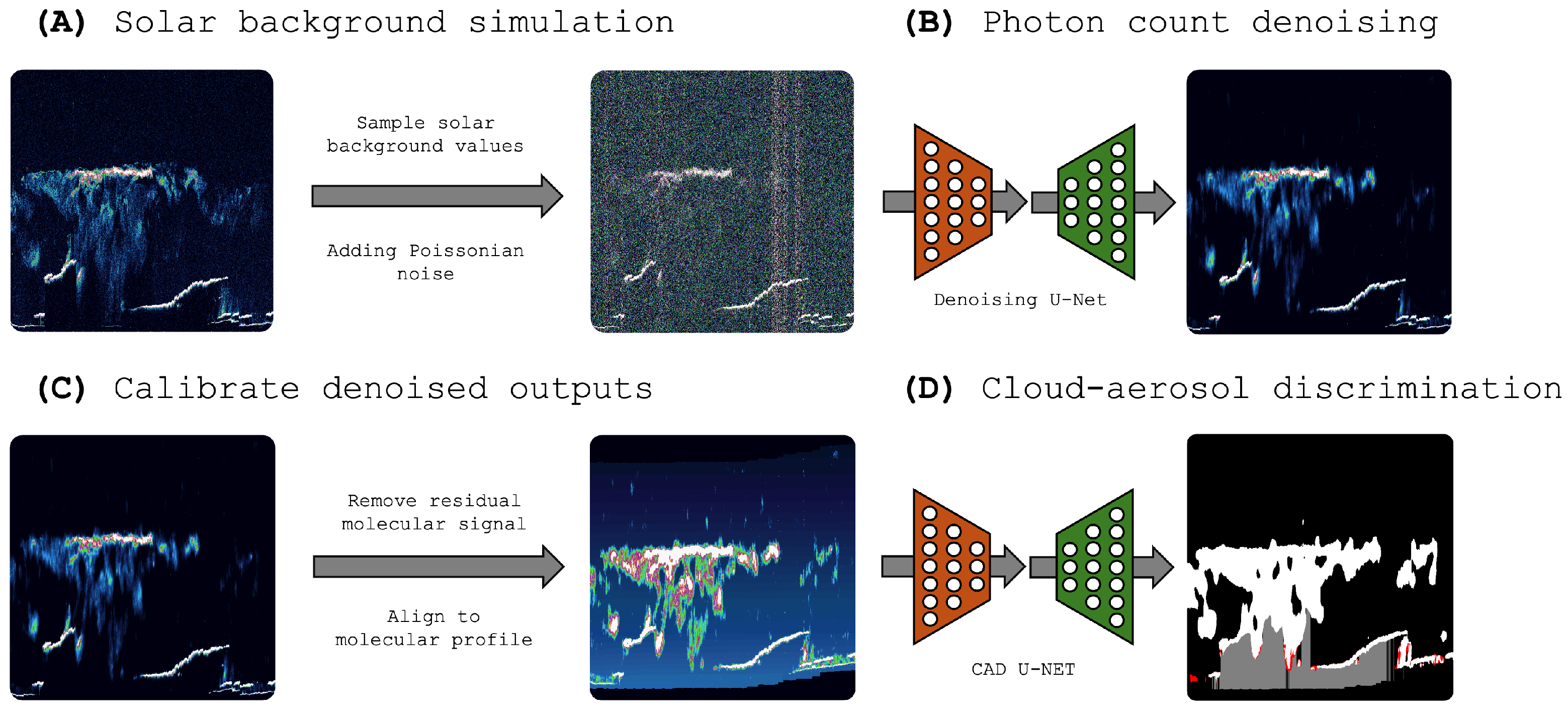

2.2. Solar Background Simulation

2.3. Vertical Feature Mask

3. Methods

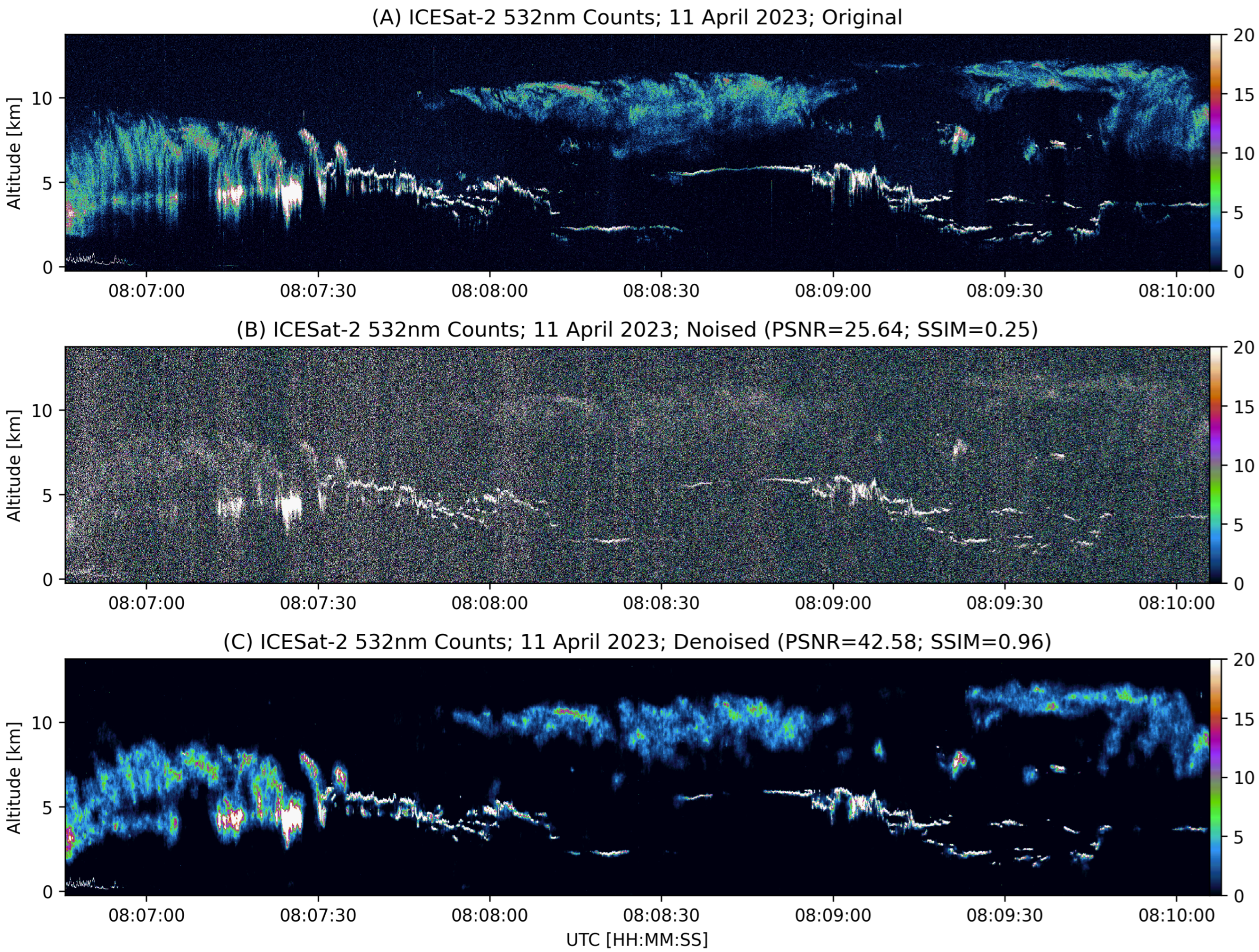

3.1. Photon Count Denoising

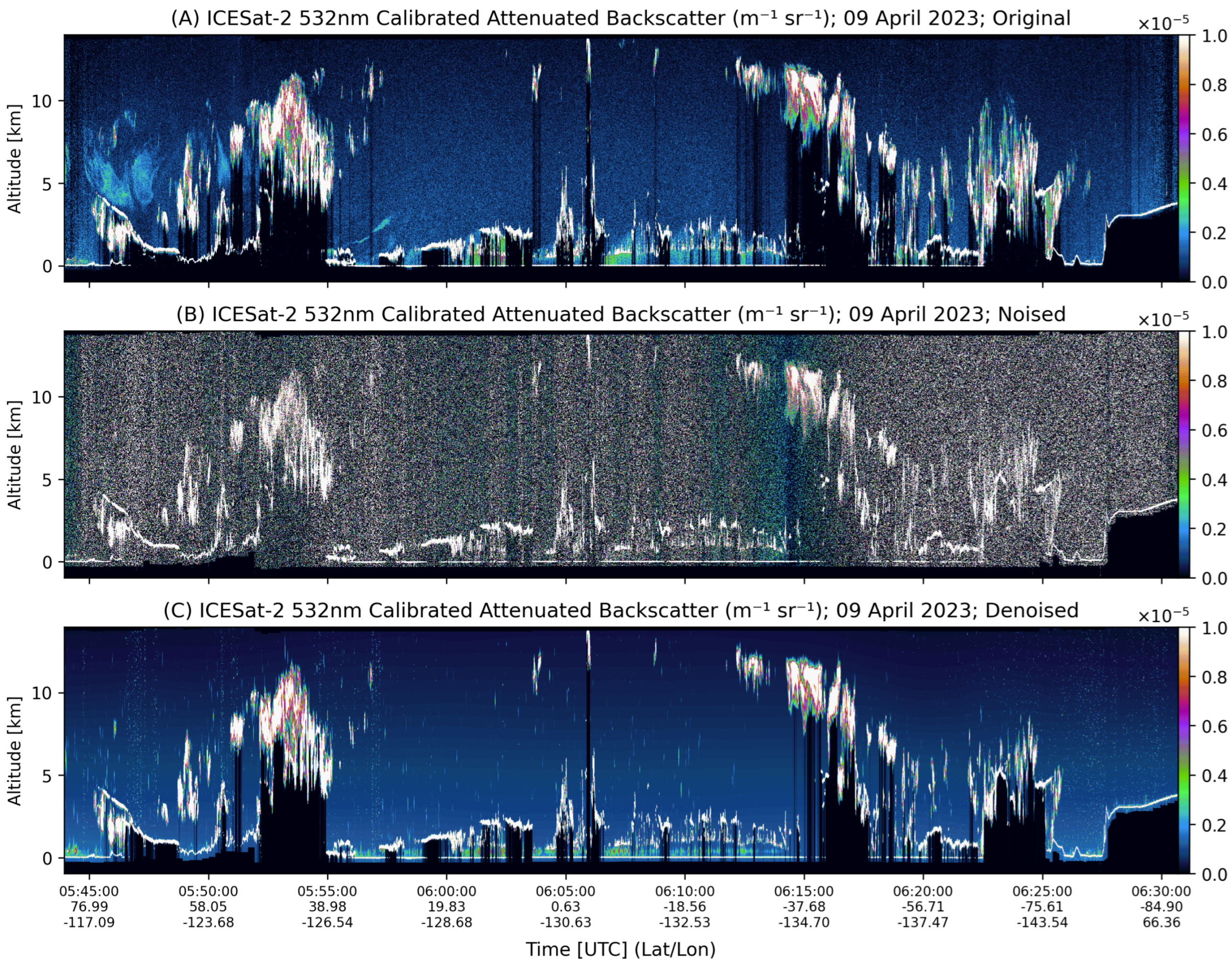

3.2. Calibrated Attenuated Backscatter

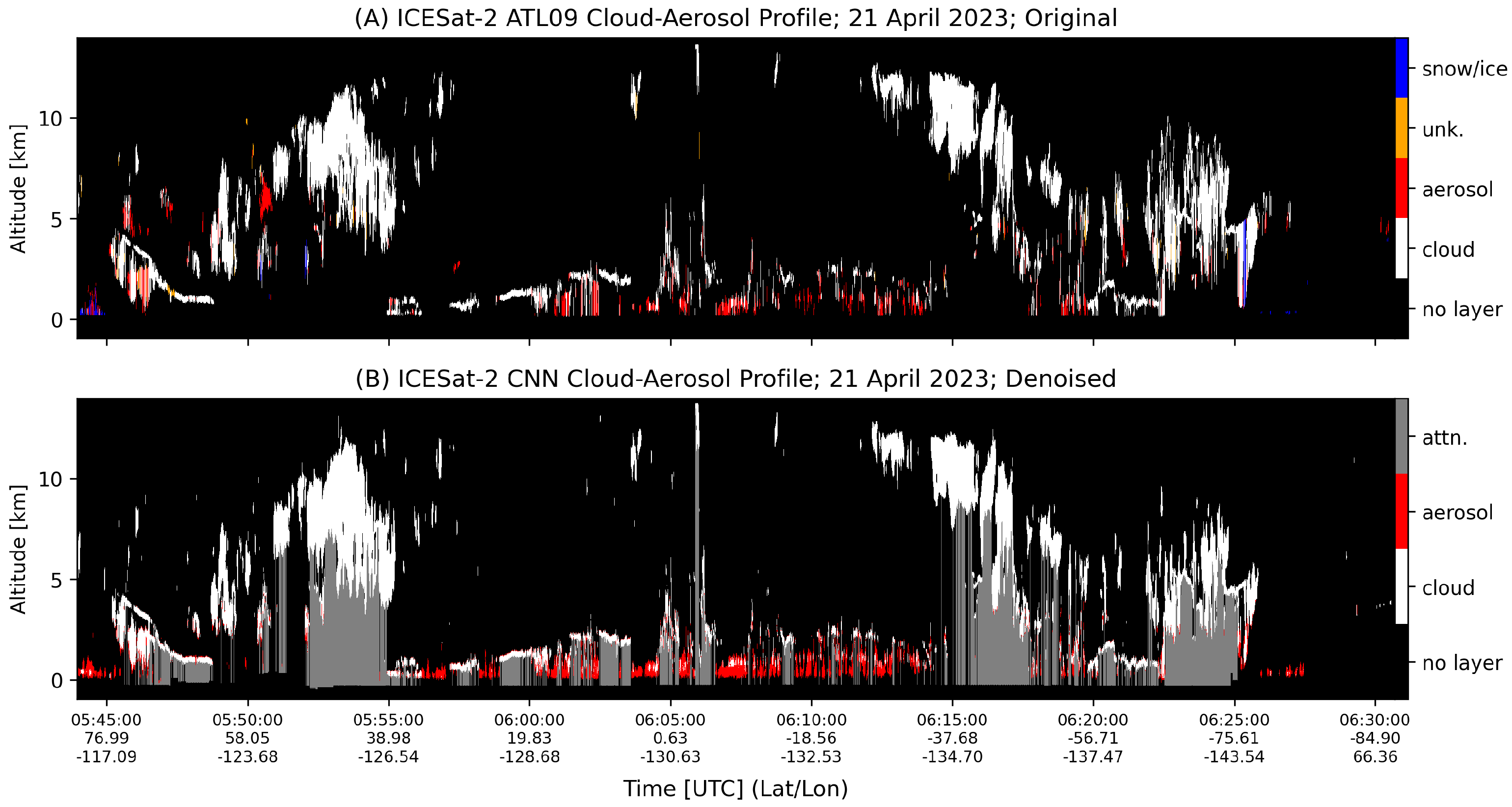

3.3. Cloud–Aerosol Discrimination

4. Computational Details

4.1. Dataset Construction

4.2. Convolutional Neural Network

4.3. Signal Quality Metrics

4.4. Classification Evaluation

4.5. Implementation Details

5. Performance Assessment Using Simulated Data

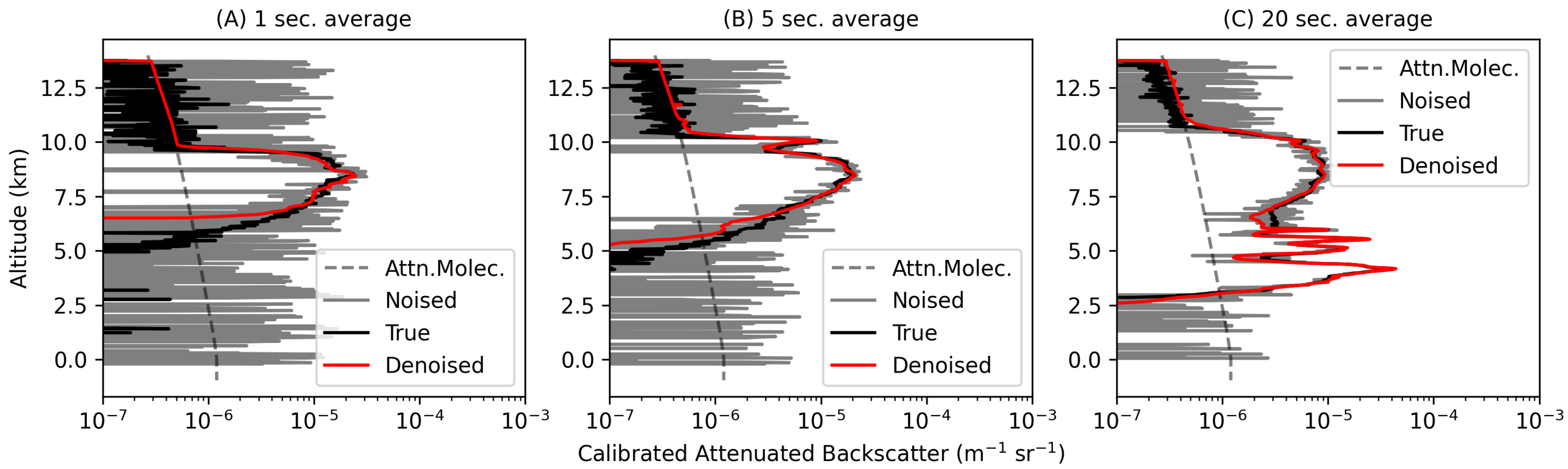

5.1. Denoising

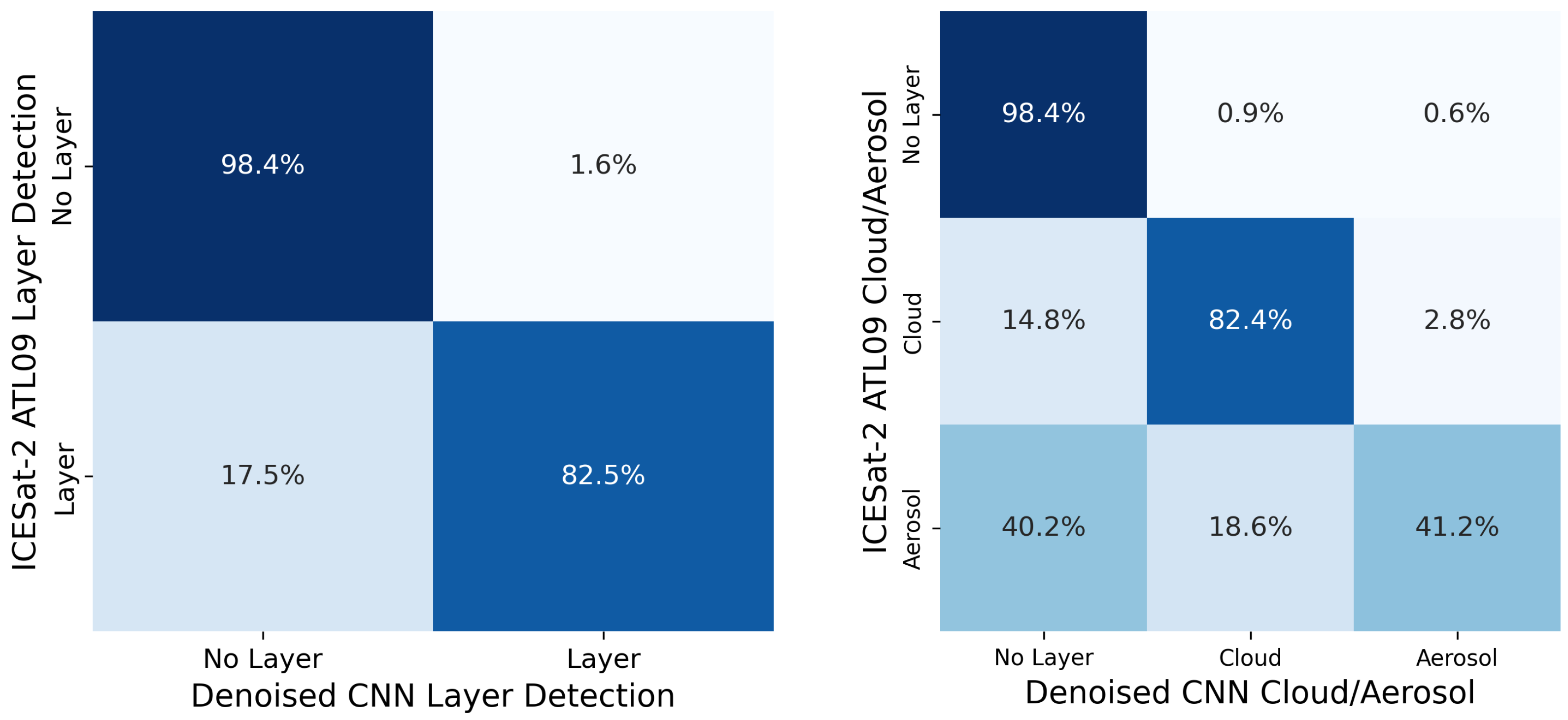

5.2. Layer Detection and Cloud–Aerosol Discrimination

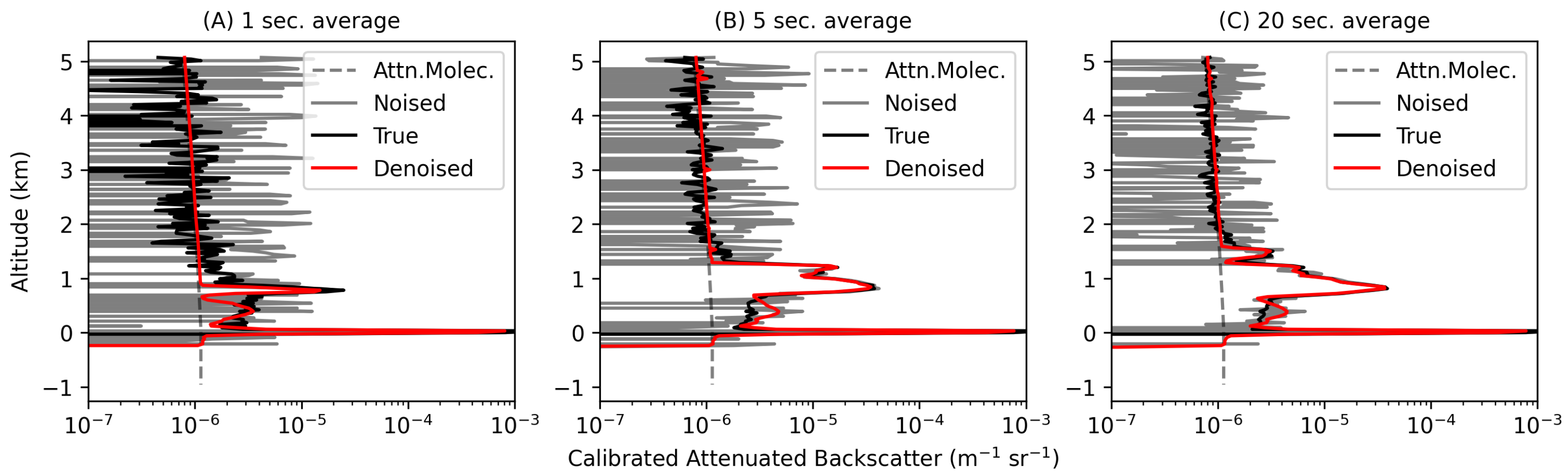

5.3. Single Profile Comparisons

5.4. Summary Statistics

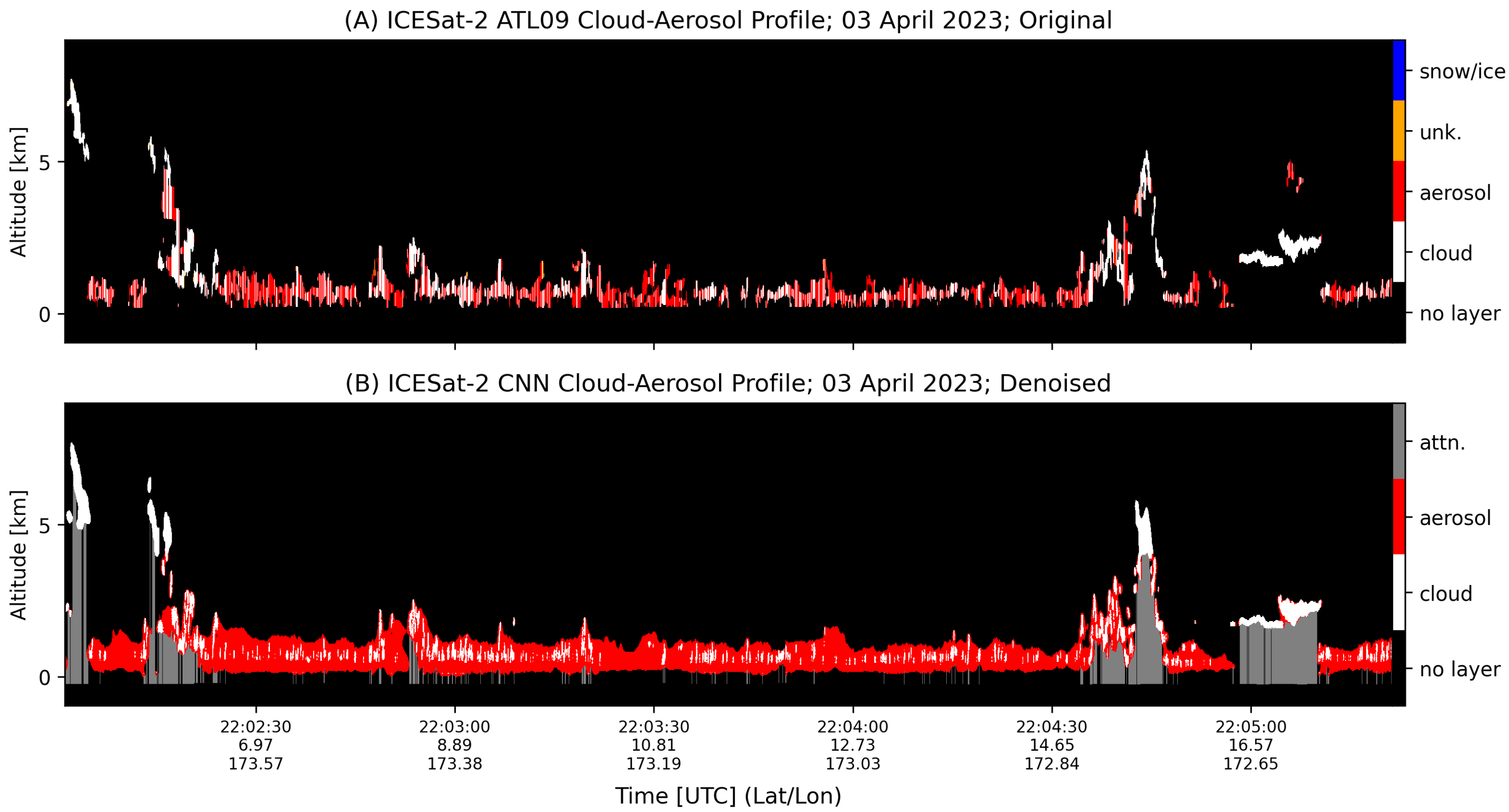

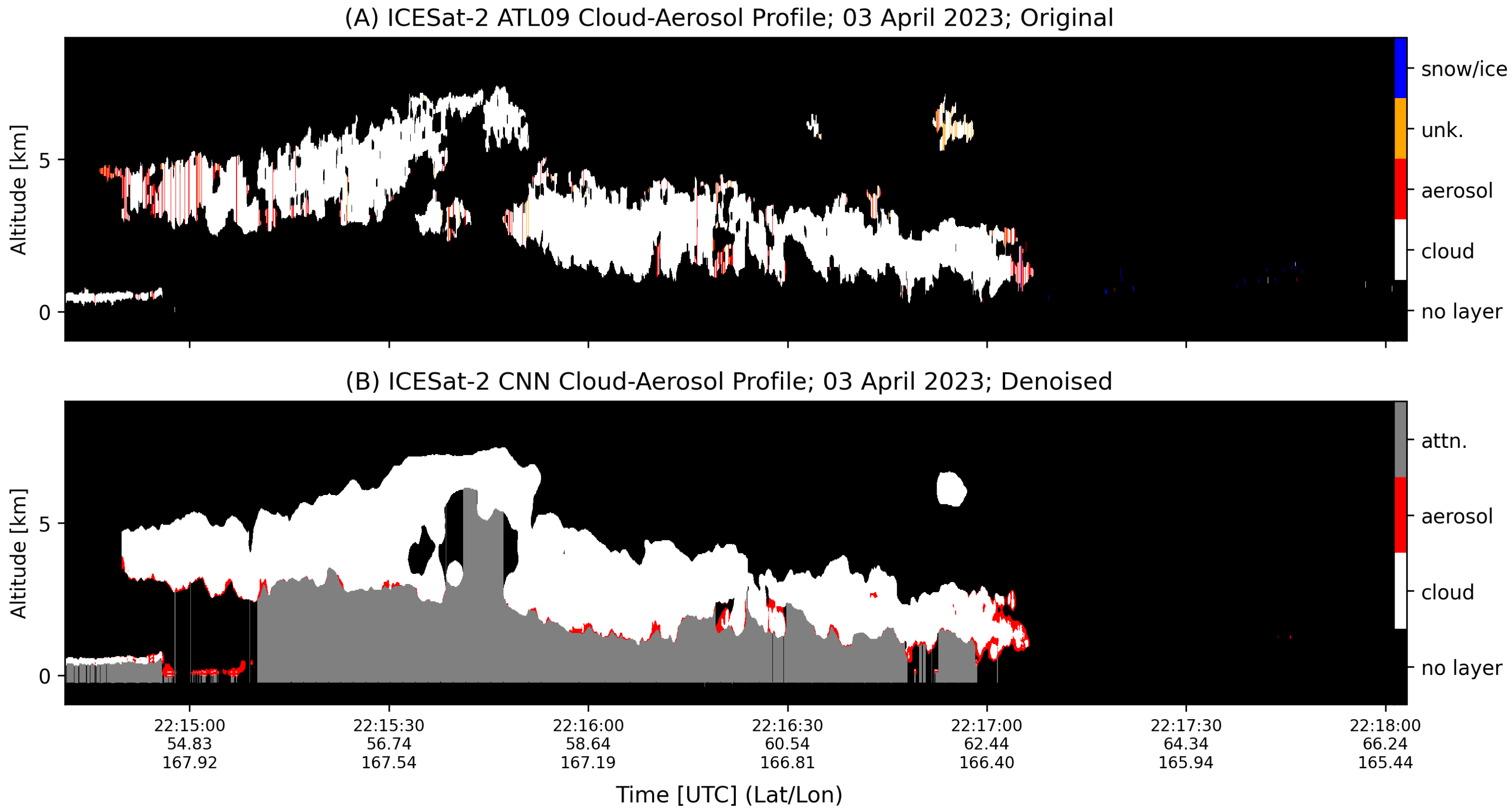

6. Cloud–Aerosol Discrimination Using Real ICESat-2 Daytime Data

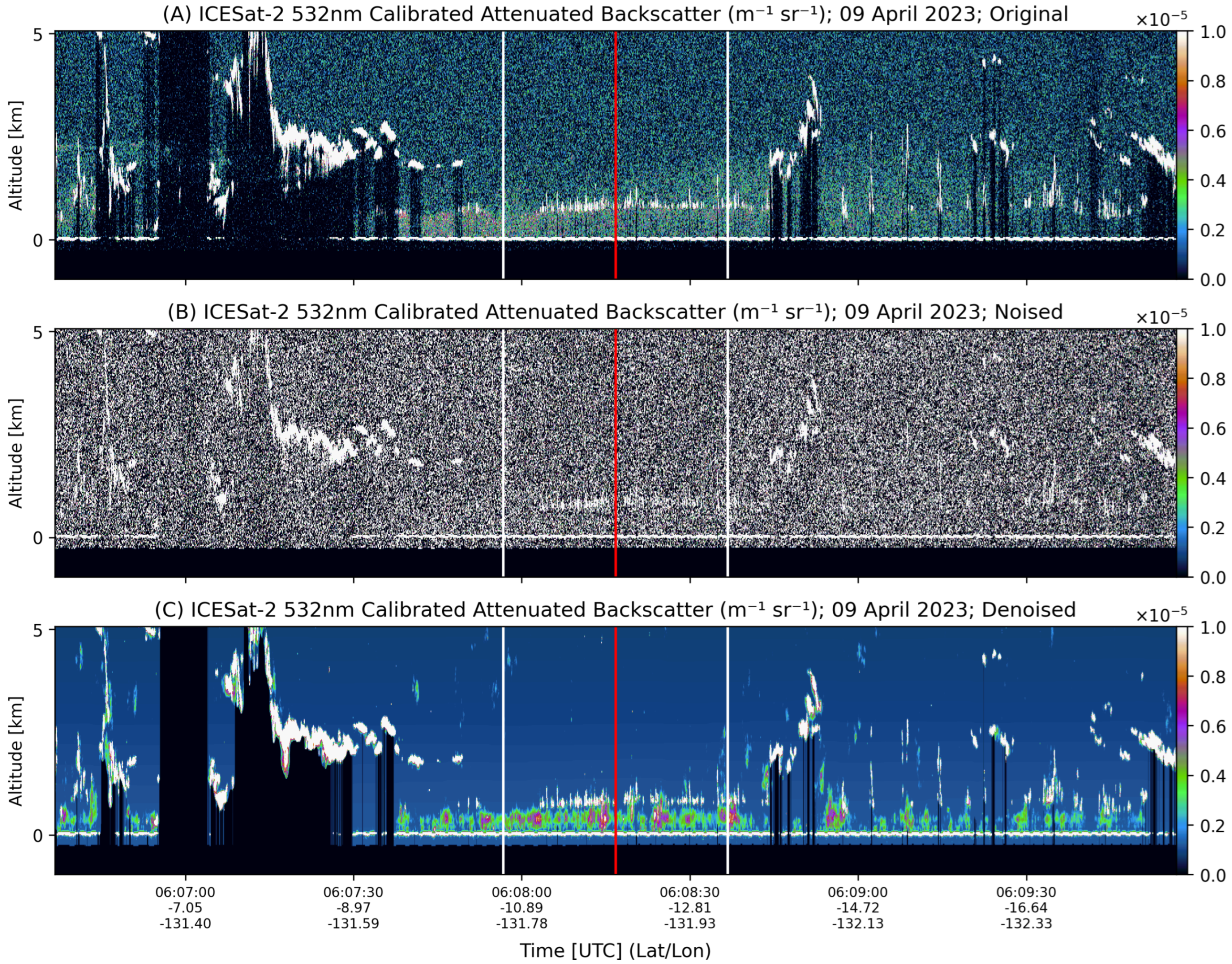

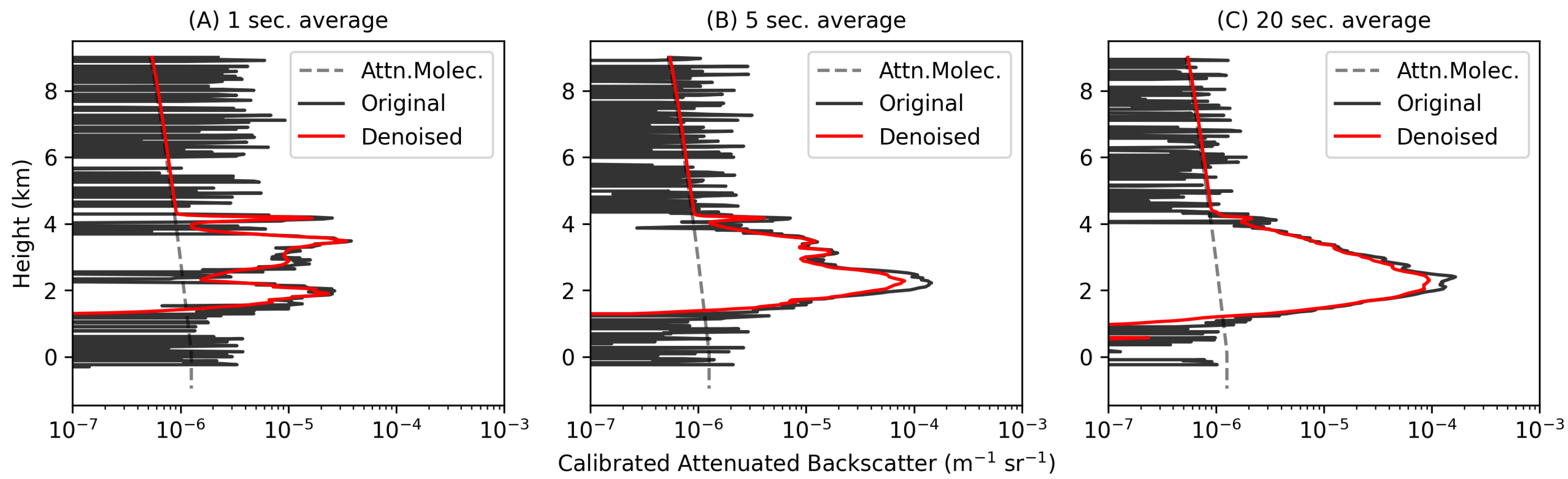

6.1. Denoising

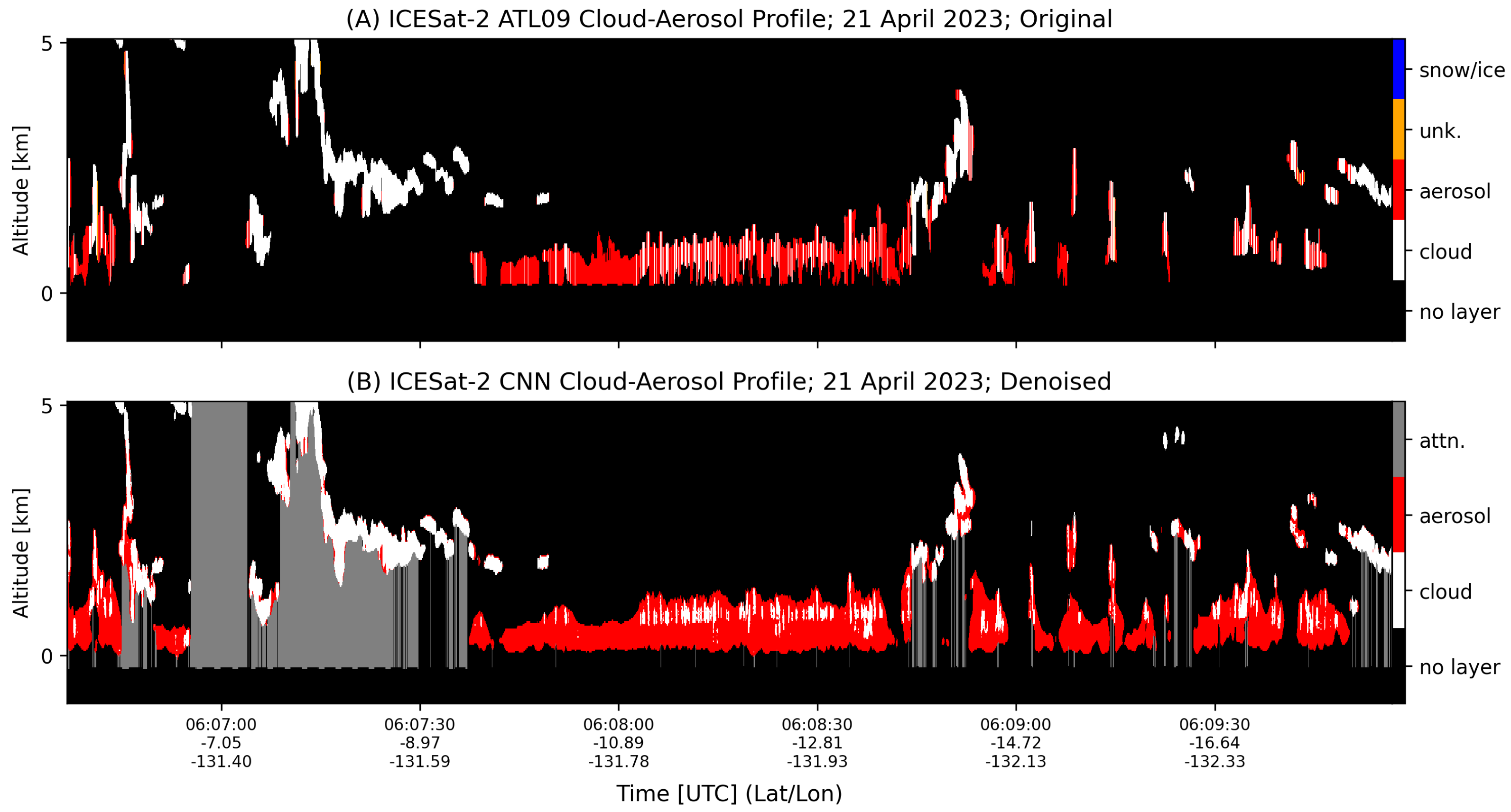

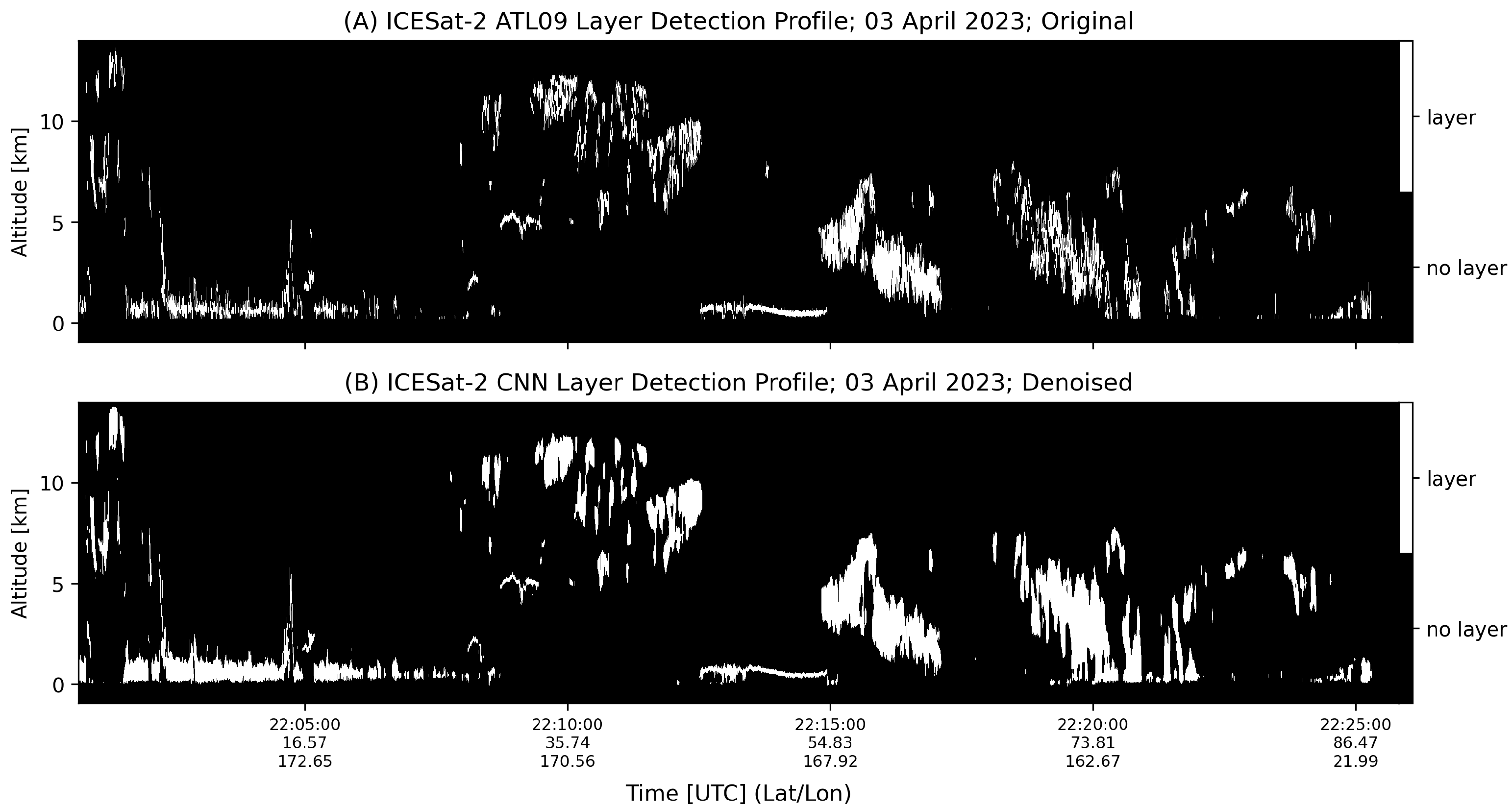

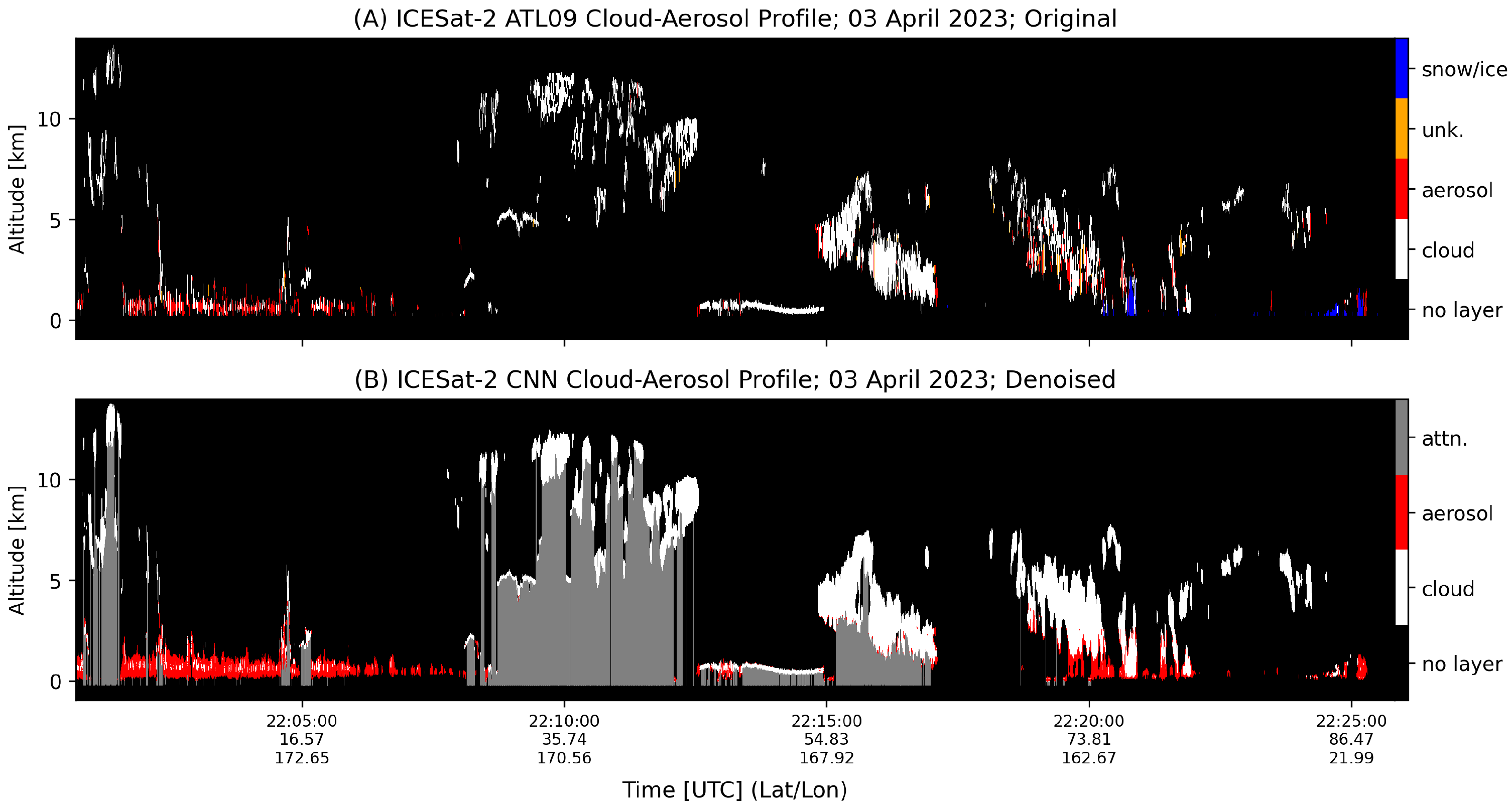

6.2. Layer Detection and Cloud–Aerosol Discrimination

6.3. Single Profile Comparisons

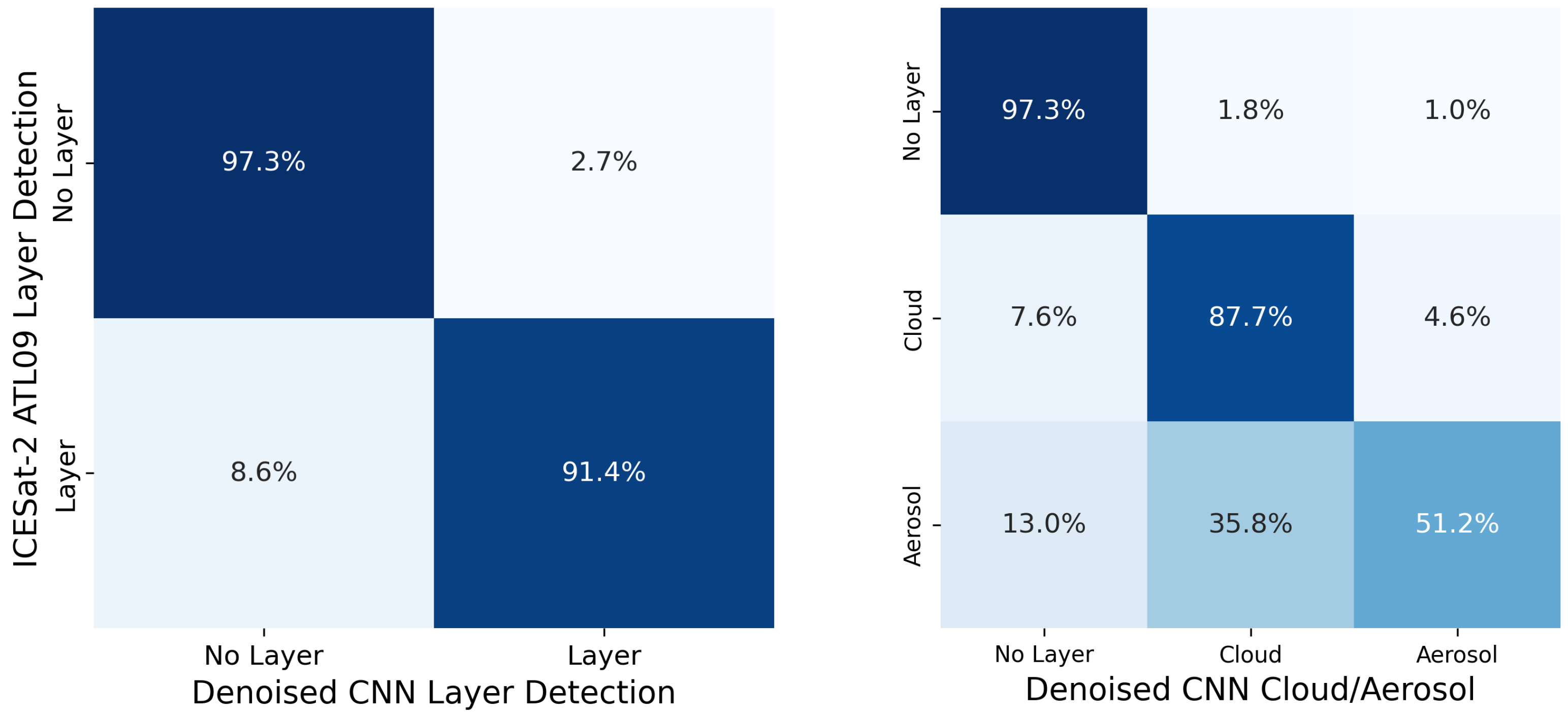

6.4. Summary Statistics

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGill, M.; Hlavka, D.; Hart, W.; Scott, V.S.; Spinhirne, J.; Schmid, B. Cloud physics lidar: Instrument description and initial measurement results. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 3725–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.J.; Yorks, J.E.; Scott, V.S.; Kupchock, A.W.; Selmer, P.A. The cloud-aerosol transport system (CATS): A technology demonstration on the international space station. In Proceedings of the Lidar Remote Sensing for Environmental Monitoring XV, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–13 August 2015; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 9612, pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifer, I.; Melton, C.; Chatfield, R.; Cui, X.; Fischer, M.L.; Fladeland, M.; Gore, W.; Hlavka, D.L.; Iraci, L.T.; Marrero, J.; et al. Air pollution inputs to the Mojave Desert by fusing surface mobile and airborne in situ and airborne and satellite remote sensing: A case study of interbasin transport with numerical model validation. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 224, 117184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowottnick, E.P.; Christian, K.E.; Yorks, J.E.; McGill, M.J.; Midzak, N.; Selmer, P.A.; Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Salinas, S.V. Aerosol detection from the cloud–aerosol transport system on the international space station: Algorithm overview and implications for diurnal sampling. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, S.; McGill, M.; Gomes, J.; Selmer, P.; Finneman, G.; Begolka, J. Global Aerosol Climatology from ICESat-2 Lidar Observations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiskova, M.; Stiller, O. Development of Strategies for Radar and Lidar Data Assimilation; European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts: Reading, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama, T.; Tanaka, T.; Shimizu, A.; Miyoshi, T. Data assimilation of CALIPSO aerosol observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Campbell, J.R.; Reid, J.S.; Westphal, D.L.; Baker, N.L.; Campbell, W.F.; Hyer, E.J. Evaluating the impact of assimilating CALIOP-derived aerosol extinction profiles on a global mass transport model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L14801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.; Yorks, J.; Krotkov, N.; Da Silva, A.; McGill, M. Using CATS near-real-time lidar observations to monitor and constrain volcanic sulfur dioxide (SO2) forecasts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 11-089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.J.; Swap, R.J.; Yorks, J.E.; Selmer, P.A.; Piketh, S.J. Observation and quantification of aerosol outflow from southern Africa using spaceborne lidar. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2020, 116, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favrichon, S.; Prigent, C.; Jimenez, C.; Aires, F. Detecting cloud contamination in passive microwave satellite measurements over land. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 1531–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, R.; Ackerman, S.; Nagle, F.; Frey, R.; Dutcher, S.; Kuehn, R.; Vaughan, M.; Baum, B. Global Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) cloud detection and height evaluation using CALIOP. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D00A19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hasekamp, O.; van Diedenhoven, B.; Cairns, B.; Yorks, J.E.; Chowdhary, J. Passive remote sensing of aerosol layer height using near-UV multiangle polarization measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 8783–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorks, J.E.; Selmer, P.A.; Kupchock, A.; Nowottnick, E.P.; Christian, K.E.; Rusinek, D.; Dacic, N.; McGill, M.J. Aerosol and cloud detection using machine learning algorithms and space-based lidar data. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.J.; Selmer, P.A.; Kupchock, A.W.; Yorks, J.E. Machine learning-enabled real-time detection of cloud and aerosol layers using airborne lidar. Front. Remote Sens. 2023, 4, 1116817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Gao, L.; Redemann, J.; Flynn, C.J.; Espinosa, W.R.; da Silva, A.M.; Stamnes, S.; Burton, S.P.; Liu, X.; Ferrare, R.; et al. A combined lidar-polarimeter inversion approach for aerosol remote sensing over ocean. Front. Remote Sens. 2021, 2, 620871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, T.D.; Campbell, J.R.; Reid, J.S.; Tackett, J.L.; Vaughan, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Marquis, J.W. Minimum aerosol layer detection sensitivities and their subsequent impacts on aerosol optical thickness retrievals in CALIPSO level 2 data products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinar, E.K.; Campbell, J.R.; Lolli, S.; Ozog, S.C.; Yorks, J.E.; Camacho, C.; Gu, Y.; Bucholtz, A.; McGill, M.J. Sensitivities in satellite lidar-derived estimates of daytime top-of-the-atmosphere optically thin cirrus cloud radiative forcing: A case study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, S. Machine Learning Techniques for Vertical Lidar-Based Detection, Characterization, and Classification of Aerosols and Clouds: A Comprehensive Survey. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Wu, S.; Long, W.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y.; Sun, K.; Meng, F.; Song, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, W. Aerosol and cloud data processing and optical property retrieval algorithms for the spaceborne ACDL/DQ-1. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Mao, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. A Novel Lidar Signal Denoising Method Based on Convolutional Autoencoding Deep Learning Neural Network. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmer, P.; Yorks, J.E.; Nowottnick, E.P.; Cresanti, A.; Christian, K.E. A Deep Learning Lidar Denoising Approach for Improving Atmospheric Feature Detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorks, J.E.; Wang, J.; McGill, M.J.; Follette-Cook, M.; Nowottnick, E.P.; Reid, J.S.; Colarco, P.R.; Zhang, J.; Kalashnikova, O.; Yu, H.; et al. A SmallSat concept to resolve diurnal and vertical variations of aerosols, clouds, and boundary layer height. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E815–E836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalati, W.; Zwally, H.J.; Bindschadler, R.; Csatho, B.; Farrell, S.L.; Fricker, H.A.; Harding, D.; Kwok, R.; Lefsky, M.; Markus, T.; et al. The ICESat-2 laser altimetry mission. Proc. IEEE 2010, 98, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, T.; Neumann, T.; Martino, A.; Abdalati, W.; Brunt, K.; Csatho, B.; Farrell, S.; Fricker, H.; Gardner, A.; Harding, D.; et al. The Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2): Science requirements, concept, and implementation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 190, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, S.; Yang, Y.; Herzfeld, U.; Hancock, D. ICESat-2 Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document for the Atmosphere, Part I: Level 2 and 3 Data Products; Version 6; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Goddard Space Flight Center: Glenn Dale, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld, U.C.; Trantow, T.M.; Harding, D.; Dabney, P.W. Surface-height determination of crevassed glaciers—Mathematical principles of an autoadaptive density-dimension algorithm and validation using ICESat-2 simulator (SIMPL) data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 1874–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzfeld, U.; Hayes, A.; Palm, S.; Hancock, D.; Vaughan, M.; Barbieri, K. Detection and height measurement of tenuous clouds and blowing snow in ICESat-2 ATLAS data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL093473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). ICESat-2 Data Products; National Snow and Ice Data Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2025; Available online: https://nsidc.org/data/icesat-2 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Proceedings, Part III 18. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, B.; Gomes, J.; McGill, M.; Selmer, P. Leveraging deep learning as a new approach to layer detection and cloud–aerosol classification using ICESat-2 atmospheric data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer, E.; Long, J.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2015), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32, pp. 8024–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; Van Der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, J.; McGill, M.J.; Selmer, P.A.; Kuang, S. A Deep Learning Approach to Lidar Signal Denoising and Atmospheric Feature Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244060

Gomes J, McGill MJ, Selmer PA, Kuang S. A Deep Learning Approach to Lidar Signal Denoising and Atmospheric Feature Detection. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244060

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Joseph, Matthew J. McGill, Patrick A. Selmer, and Shi Kuang. 2025. "A Deep Learning Approach to Lidar Signal Denoising and Atmospheric Feature Detection" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244060

APA StyleGomes, J., McGill, M. J., Selmer, P. A., & Kuang, S. (2025). A Deep Learning Approach to Lidar Signal Denoising and Atmospheric Feature Detection. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4060. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244060