From Graph Synchronization to Policy Learning: Angle-Synchronized Graph and Bilevel Policy Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection

Highlights

- We proposed the ASBPNet framework that significantly improves oriented object detection through geometric alignment and policy adaptation.

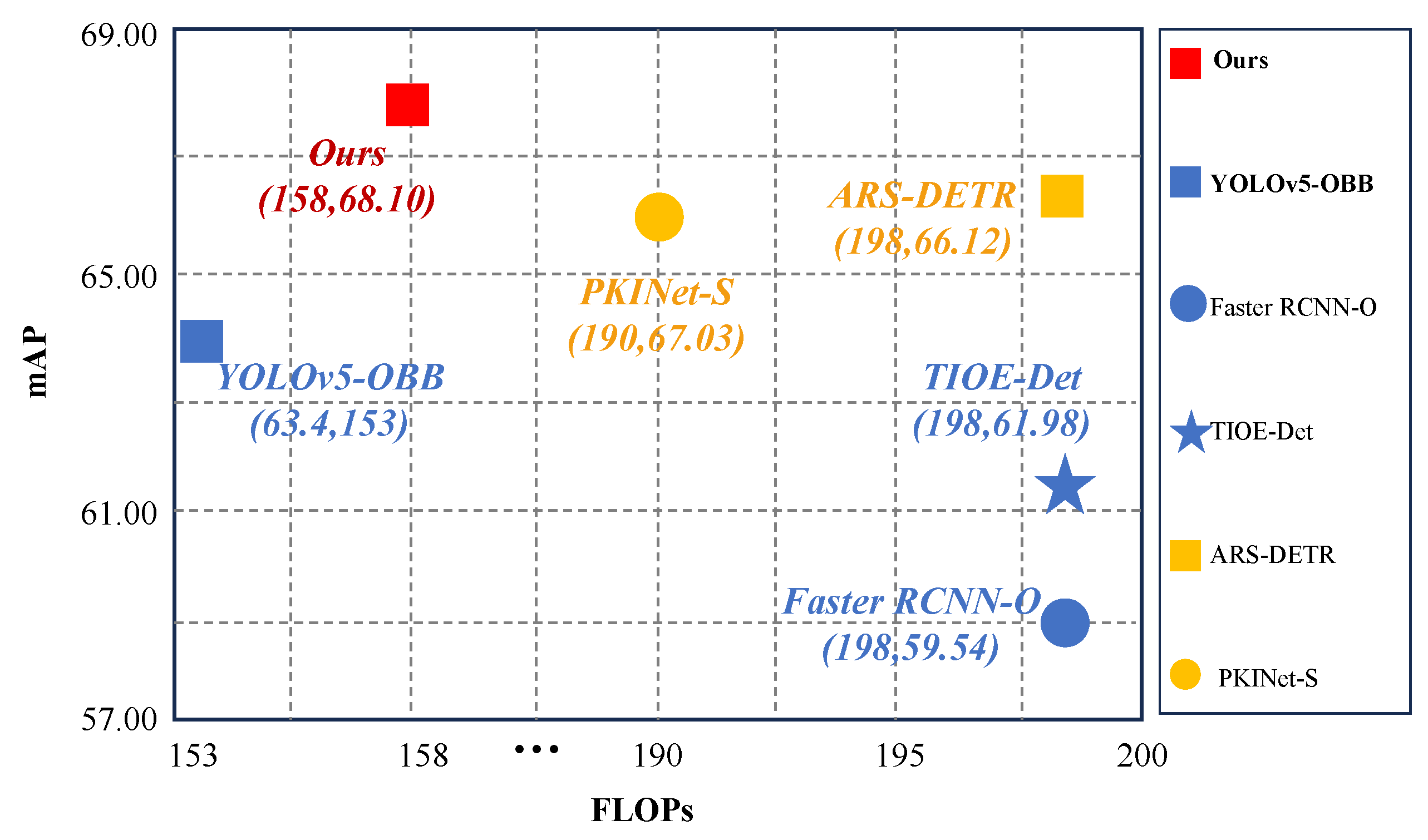

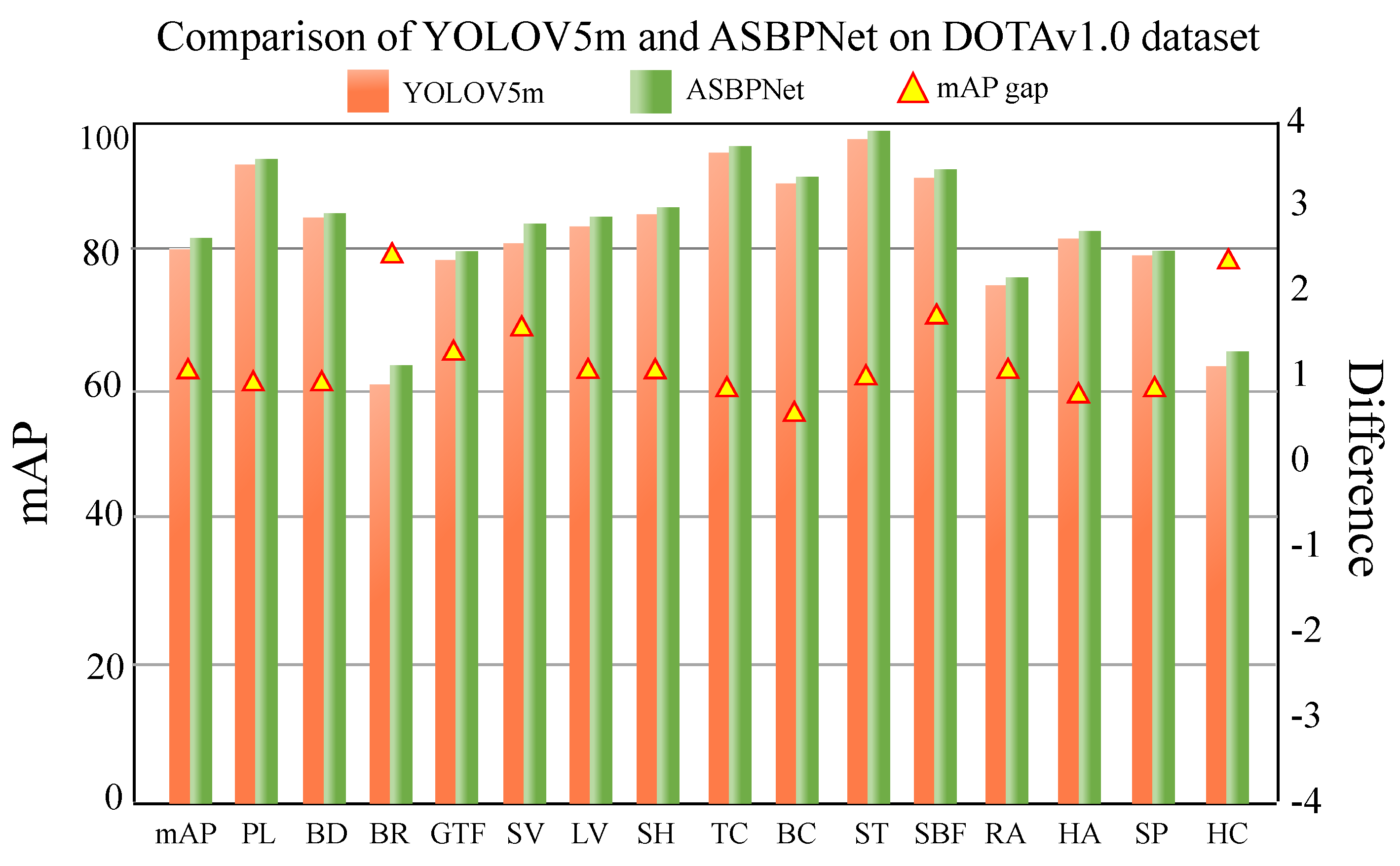

- We achieved breakthrough performance: 68.10% mAP on DIOR-R, 98.20% mAP (12) on HRSC2016, and 79.60% mAP on DOTA-v1.0.

- The framework improves geometric stability and localization accuracy while remaining lightweight, achieving a balanced, efficient solution for high-density small object detection.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The dual constraints of limited training efficiency and lack of small-target recall. Although multi-strategy combinations can improve the performance of the model in different scenarios, the traditional detection process often splits the execution of enhancement, assignment, cropping, and post-processing strategies, and the lack of global synergy and dynamic adaptation mechanisms between strategies leads to slow convergence of training and weak generalization ability of strategy migration. At the same time, the existing strategies are often insufficient to model the distribution and scale sensitivity of small targets, which makes it difficult to effectively improve the edge-detection capability and small-target recall rate, and ultimately affects the overall robustness and consistency of precision.

- Boundary fitting and angular consistency bottlenecks for rotating small targets. Small- and medium-scale targets in remote sensing images often show the characteristics of tiny size, changing attitude, and fuzzy boundary, which makes the rotation detection task face double challenges in returning to the frame boundary and maintaining the angular stability. Traditional methods often ignore the rotational correlation between candidate frames, and it is difficult to achieve the synergistic optimization of angular alignment and boundary correction, resulting in target edge drift and rotational angle jitter, which is especially obvious in multi-target dense scenarios.

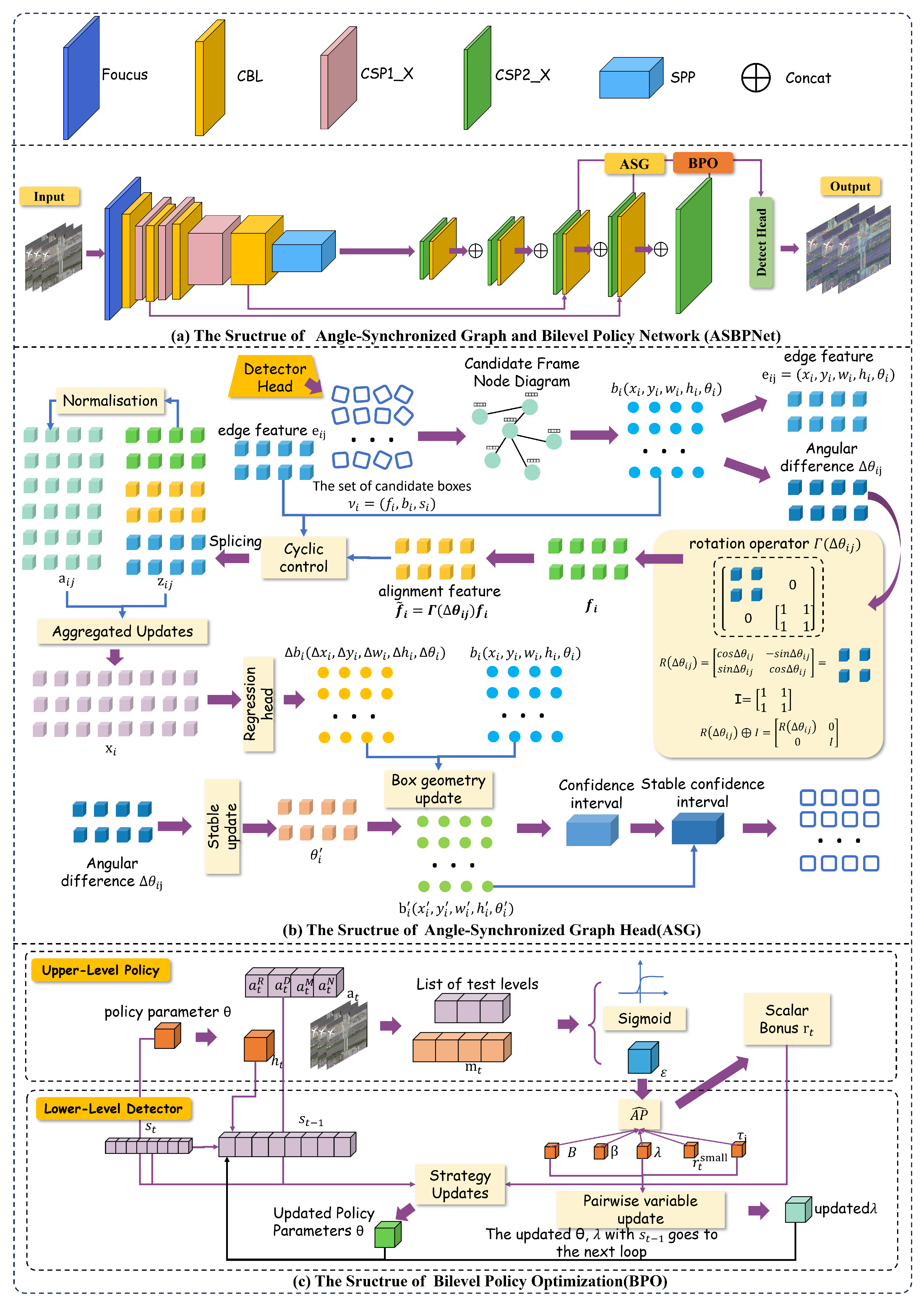

- We propose a deeply integrated approach that unifies graph-based geometric modeling and reinforcement learning-based policy optimization. This is achieved by synergizing an Angle-Synchronized Graph Head (ASG), which solves angular inconsistency and boundary jitter through equivariant message passing, and a Bilevel Policy Optimization (BPO) module, which overcomes the fragmentation of non-differentiable strategies in training and inference.

- To solve the problems of boundary instability and poor rotational robustness in the detection of remotely sensed targets at arbitrary angles, we propose the Angle-Synchronized Graph Head (ASG). Inspired by geometric equivariance and residual learning, this module enhances the angular consistency by introducing synapse-level equivariance constraints, and achieves the boundary refinement of candidate frames with the help of the micro-residual gating mechanism. It significantly improves the angle prediction accuracy and boundary alignment effect for small targets and dense structures.

- To alleviate the problem of training–inference inconsistency and delayed feedback during multi-strategy decision-making, we propose the Bilevel Policy Optimization (BPO). This module achieves consistent modeling of training and inference policies through a two-layer optimization framework combining microagentable metrics with a delayed pairing mechanism to improve the generalization and model robustness of detection policies.

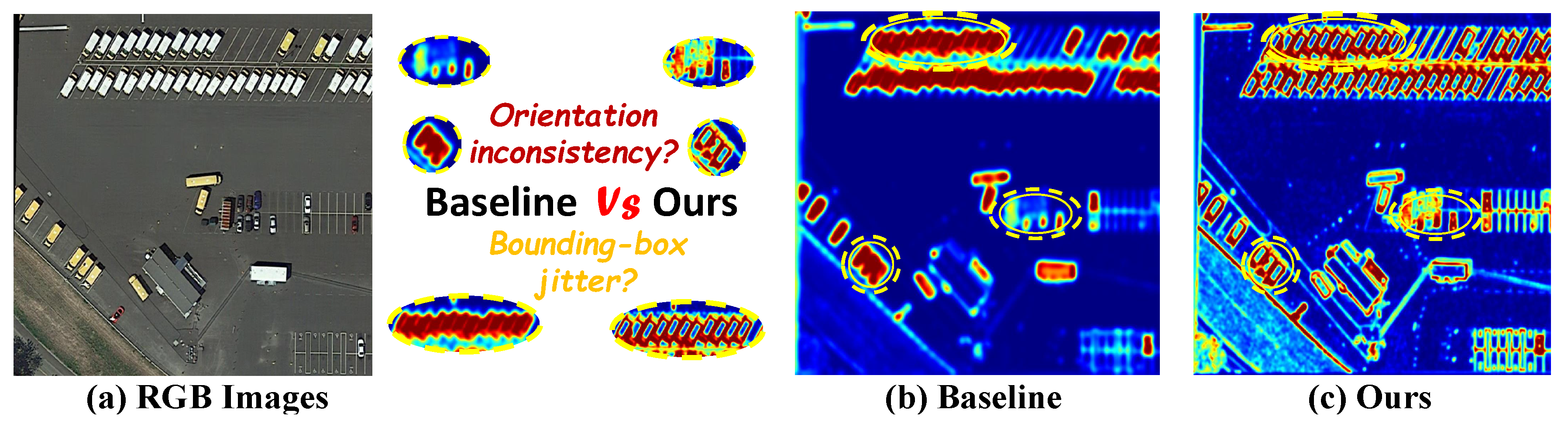

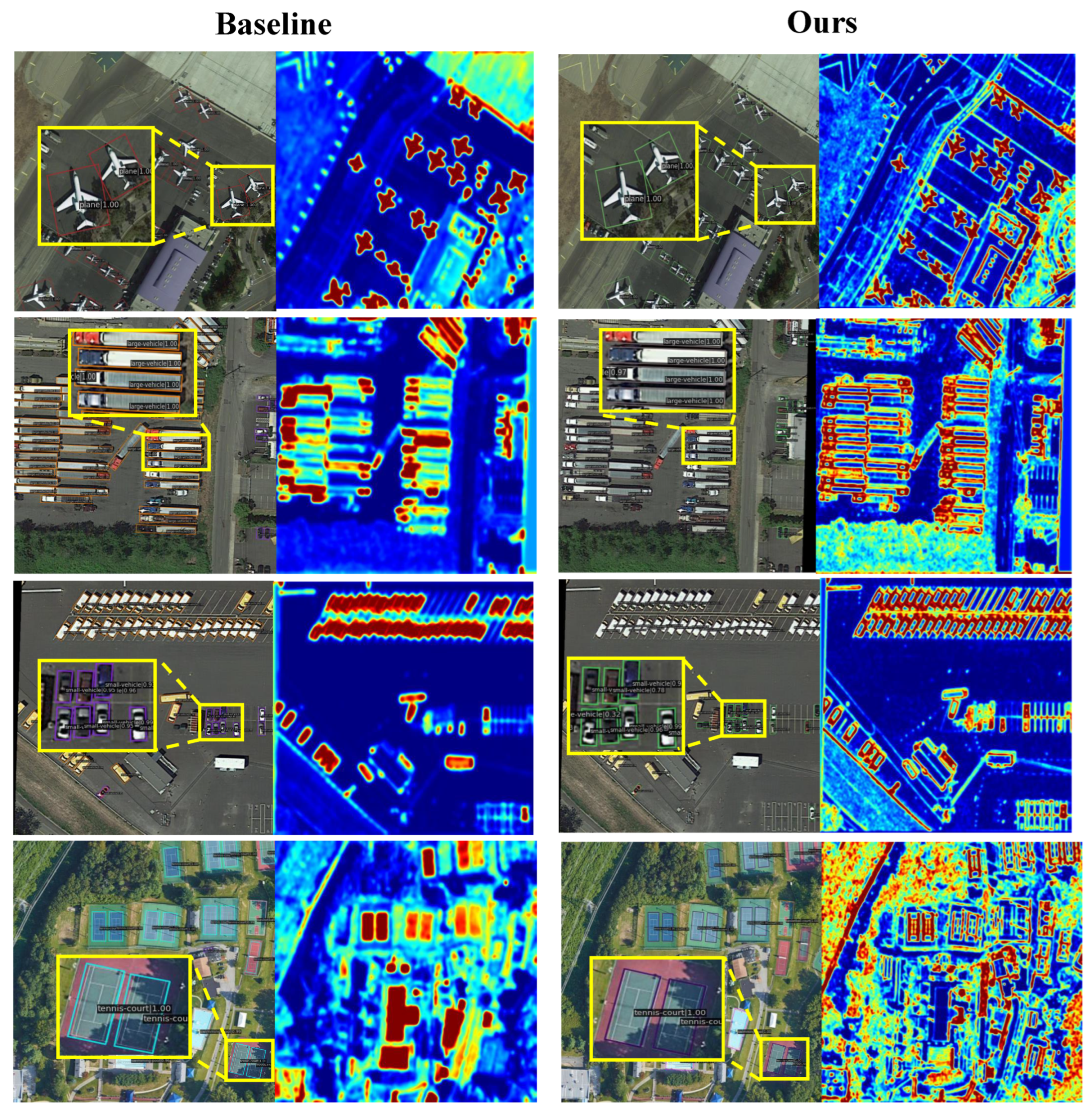

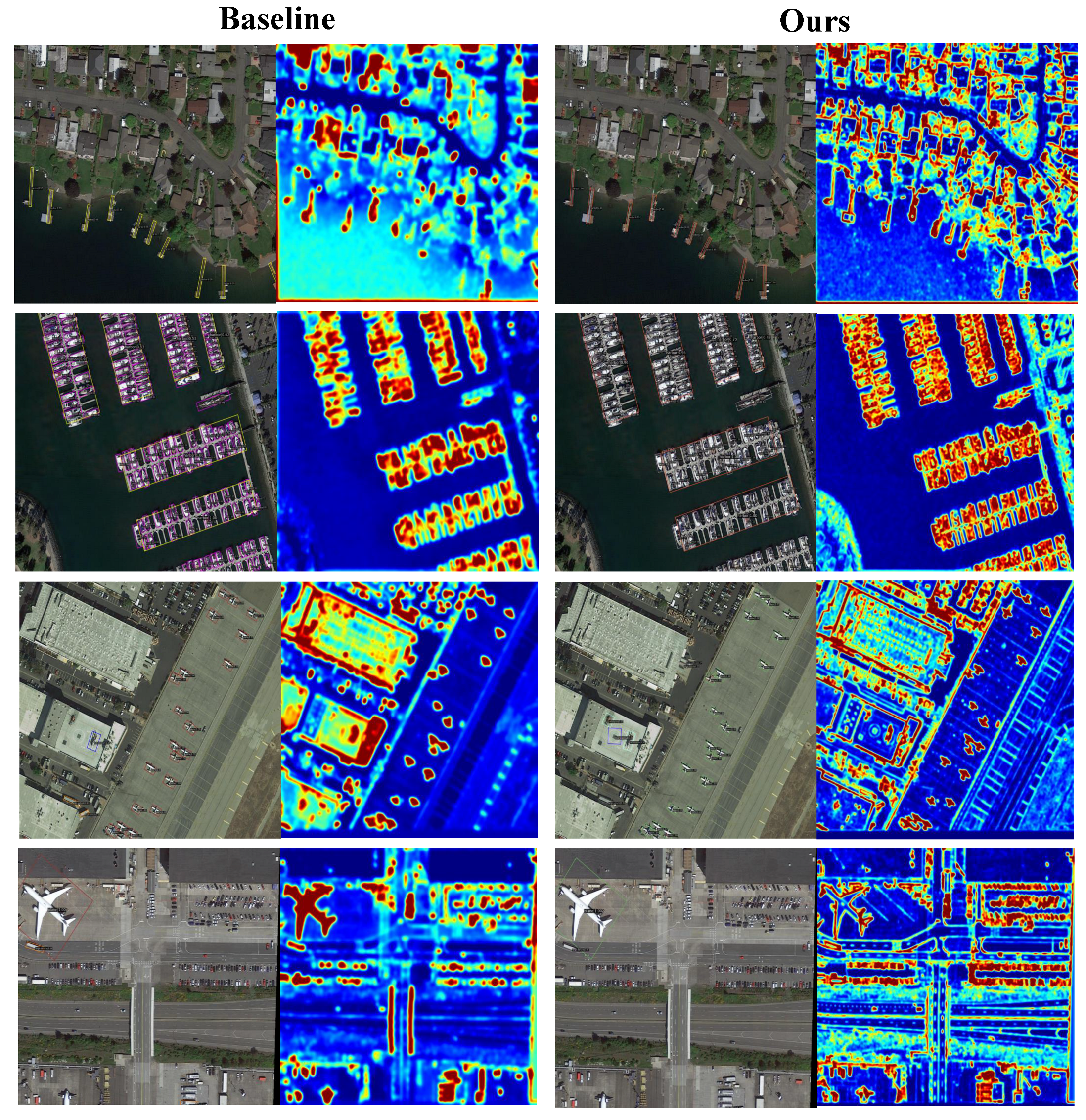

- We conducted systematic evaluations on DIOR-R, HRSC2016, and DOTAv1.0. On the DIOR-R dataset, ASBPNet improves the mAP of the baseline from 63.40% to 68.10% with only a slight increase in parameters and computation; on the HRSC2016 dataset, it achieves 98.2% mAP (12), which is a new performance for similar models. Meanwhile, the heatmap visualization demonstrates that this method has stronger target-focusing and interference-suppression ability, which significantly reduces the misdetection rate in complex backgrounds and is especially suitable for high-density and small-target scenarios in the field of remote sensing.

2. Related Work

2.1. Graph Neural Network in Remote Sensing Object Detection

2.2. Intensive Learning in Remote Sensing Object Detection

3. Methodology

3.1. Baseline: YOLOv5-OBB

3.2. Angle-Synchronized Graph Head (ASG)

3.3. Bilevel Policy Optimization (BPO)

- Upper-Level Policy: This acts as the strategic planner, implemented as a reinforcement learning agent. It observes the detection system’s performance metrics and latency status, then outputs optimized parameters for the four core strategies: rotation augmentation, sample assignment, multi-tile scanning, and rotated NMS. This policy is trained to maximize a compound reward that balances accuracy improvements against computational costs, with an adaptive dual variable enforcing the latency constraint through projected ascent updates.

- Lower-Level Detector: This serves as the tactical executor, comprising the core detection network including the ASG module. It receives strategy configurations from the upper level as fixed hyperparameters, executes the detection task, and returns performance measurements. A key component is its differentiable performance surrogate that enables effective policy learning by approximating non-differentiable evaluation metrics.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Experiments Settings

5. Results in Classic Datasets

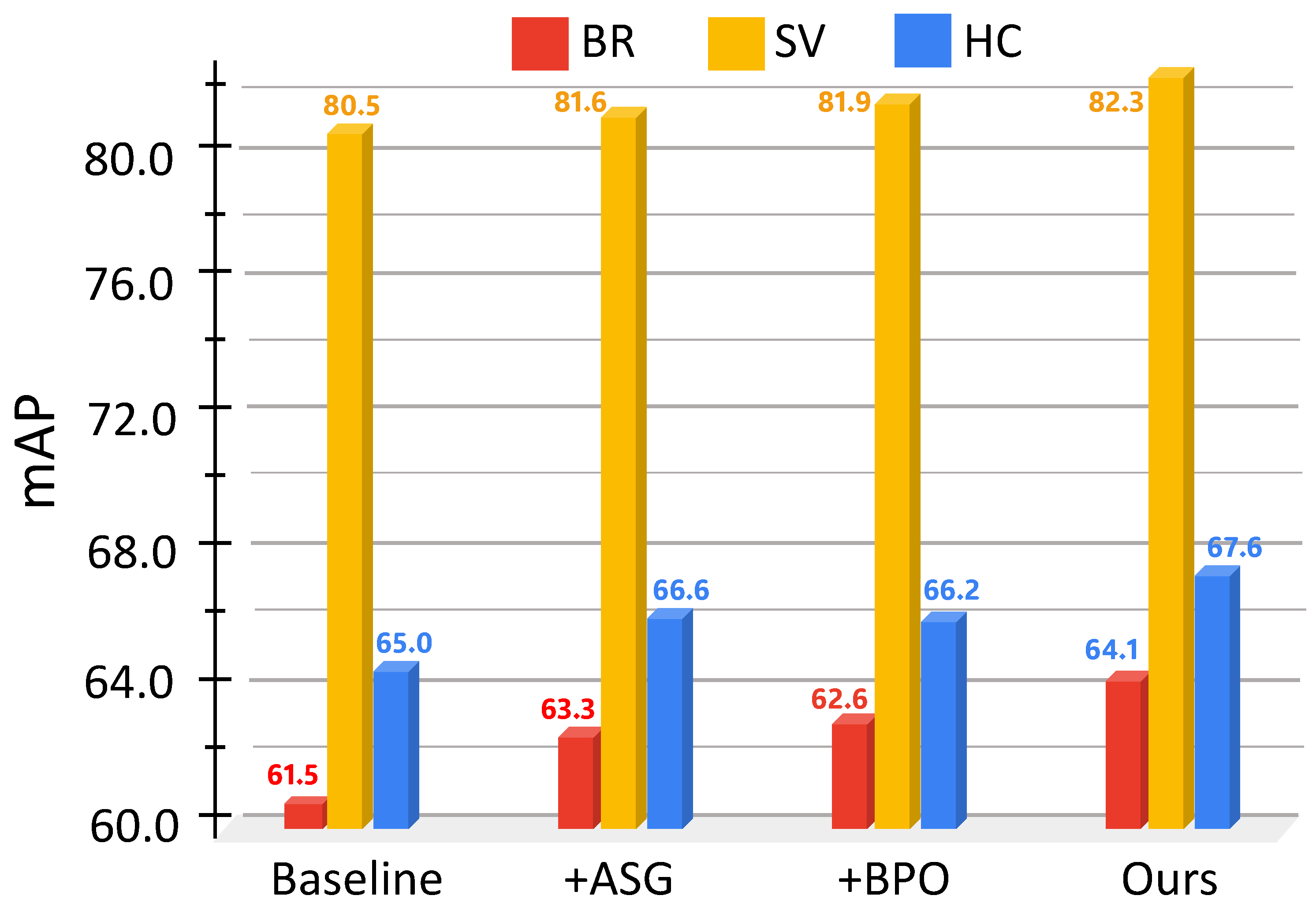

Ablation Study

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASBPNet | Edge Feature and Particle Focusing Network |

| ASG | Angle-Synchronized Graph Head |

| BPO | Bilevel Policy Optimization |

References

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, J.; Lei, L.; Zou, H. Multi-scale object detection in remote sensing imagery with convolutional neural networks. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 145, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J. A survey on object detection in optical remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 117, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, J.; Fang, Y. Few-shot object detection on remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5601614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Du, Q.; Wang, Q. ABNet: Adaptive balanced network for multiscale object detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5614914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, P.; Viegas, D.X.; Viegas, C. Vegetation mapping with random forest using sentinel 2 and GLCM texture feature—A case study for Lousã region, Portugal. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, G.; Chen, H.B.; Jing, N.; Wang, Q. Scale adaptive proposal network for object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Dong, Y. YOLO-SE: Improved YOLOv8 for remote sensing object detection and recognition. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Yi, J.; Song, Y.; Chehri, A. Small object detection based on deep learning for remote sensing: A comprehensive review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gong, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, W. Object detection in remote sensing images based on a scene-contextual feature pyramid network. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, K.; Chen, G.; Tan, X.; Zhang, L.; Dai, F.; Liao, P.; Gong, Y. Geospatial object detection on high resolution remote sensing imagery based on double multi-scale feature pyramid network. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Cai, H.; Qian, Y. Incremental detection of remote sensing objects with feature pyramid and knowledge distillation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 60, 5600413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Liang, Y. Object detection of remote sensing image based on multi-scale feature fusion and attention mechanism. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 8619–8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarian, S.; Valente, J.; Van Der Voort, M.; Tekinerdogan, B. Effect of attention mechanism in deep learning-based remote sensing image processing: A systematic literature review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Jiang, J. MTSCD-Net: A network based on multi-task learning for semantic change detection of bitemporal remote sensing images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Guo, H.; Lu, J.; Ding, L.; Yu, D. SMNet: Symmetric multi-task network for semantic change detection in remote sensing images based on CNN and transformer. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; He, J.; Zhou, G.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Sui, X. Improved oriented object detection in remote sensing images based on a three-point regression method. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, J. Rotated feature network for multiorientation object detection of remote-sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 18, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Zhao, Z.; Fan, X.; Yan, X.; Yan, W.; Xin, Y. Remote sensing image object detection based on angle classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 118696–118707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.; Wu, C.; Li, W.; Tao, R. FANet: An arbitrary direction remote sensing object detection network based on feature fusion and angle classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5608811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Bruzzone, L. DiResNet: Direction-aware residual network for road extraction in VHR remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 10243–10254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. SOAM Block: A scale–orientation-aware module for efficient object detection in remote sensing imagery. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. Multi-label remote sensing image scene classification by combining a convolutional neural network and a graph neural network. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, Y. Transformer with transfer CNN for remote-sensing-image object detection. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, J.; Ju, Y.; Lam, K.M.; Wang, Q. Efficient inductive vision transformer for oriented object detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5616320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xu, C.; Cui, Z.; Yang, J. Progressive context-dependent inference for object detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 32, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kwong, S. RRNet: Relational reasoning network with parallel multiscale attention for salient object detection in optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5613311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Han, J.; Yao, X.; Cheng, G. TCANet: Triple context-aware network for weakly supervised object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 6946–6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Sun, X.; Diao, W.; Chen, K.; Xu, G.; Fu, K. Invariant structure representation for remote sensing object detection based on graph modeling. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5625217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Celik, T.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.C. AFDet: Toward more accurate and faster object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 12557–12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Chen, G.; Zhu, K.; Liao, P.; Wang, T. Object-based classification framework of remote sensing images with graph convolutional networks. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 8010905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Hu, A.; Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q. Hierarchical GNN framework for earth’s surface anomaly detection in single satellite imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5627314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrullah, C.; Panangian, D.; Bittner, K. PolyRoof: Precision roof polygonization in urban residential building with graph neural networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, G.; Tan, K.E. Holistically-nested structure-aware graph neural network for road extraction. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Visual Computing, Virtual Event, 4–6 October 2021; pp. 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Hou, B.; Wu, Q.; Ren, B.; Wang, S.; Jiao, L. Remote sensing object tracking with deep reinforcement learning under occlusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5605213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzkent, B.; Yeh, C.; Ermon, S. Efficient object detection in large images using deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Snowmass, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 1824–1833. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J. Remote sensing image caption generation via transformer and reinforcement learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 26661–26682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Gong, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, Q. Accurate object localization in remote sensing images based on convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 2486–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Lin, S.; Cheng, G.; Yao, X.; Ren, H.; Wang, W. Object detection in remote sensing images based on improved bounding box regression and multi-level features fusion. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhou, P.; Han, J. Learning rotation-invariant convolutional neural networks for object detection in VHR optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 7405–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Guo, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L. A novel multi-model decision fusion network for object detection in remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, M.; Easwaran, A.; Das, S.; Yuhas, M. Guaranteeing out-of-distribution detection in deep RL via transition estimation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.05238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, M.; Esposito, A.; Zhao, Z.; Braun, T.; Sargento, S. RL-CNN: Reinforcement learning-designed convolutional neural network for urban traffic flow estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Harbin, China, 28 June–2 July 2021; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K.; Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, G.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. A ship rotation detection model in remote sensing images based on feature fusion pyramid network and deep reinforcement learning. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, L.; Rome, E. Reinforcement learning of object detection strategies. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Intelligent Robotic Systems (SIRS), Reading, UK, 18–20 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, Z. Multiresolution airport detection via hierarchical reinforcement learning saliency model. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 2855–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Gao, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Li, W. EMO2-DETR: Efficient-matching oriented object detection with transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5616814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Li, H.C.; Zhang, H.; Xia, G.S. Learning center probability map for detecting objects in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 4307–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Wu, Z.; Song, P. AO2-DETR: Arbitrary-oriented object detection transformer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 2342–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Guo, Z.; Sun, X.; Fu, K. SCRDet: Towards more robust detection for small, cluttered and rotated objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8232–8241. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3Det: Refined single-stage detector with feature refinement for rotating object. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2849–2858. [Google Scholar]

- Yujie, L.; Xiaorui, S.; Wenbin, S.; Yafu, Y. S2ANet: Combining local spectral and spatial point grouping for point cloud processing. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 2024, 6, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xu, K.; Chen, E.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Hu, Y.; Pan, Z. Semantic attention and structured model for weakly supervised instance segmentation in optical and SAR remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Han, J. DHSNet: Deep hierarchical saliency network for salient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 678–686. [Google Scholar]

- Bharati, P.; Pramanik, A. Deep learning techniques—R-CNN to Mask R-CNN: A survey. In Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition: Proceedings of CIPR 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Xia, G.S. ReDet: A rotation-equivariant detector for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2786–2795. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q. Rethinking rotated object detection with Gaussian Wasserstein distance loss. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 11830–11841. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, J. Learning high-precision bounding box for rotated object detection via Kullback–Leibler divergence. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 18381–18394. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yan, F.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, K. A multi-scale rotated ship targets detection network for remote sensing images in complex scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Dai, Y.; Hou, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.M.; Yang, J. LSKNet: A foundation lightweight backbone for remote sensing. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 1410–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Lai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Yao, Y. Poly kernel inception network for remote sensing detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 27706–27716. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. Oriented objects as pairs of middle lines. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 169, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Q.; Miao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Dong, Y. CFC-Net: A critical feature capturing network for arbitrary-oriented object detection in remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5605814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Lu, H.; He, Y. Center-boundary dual attention for oriented object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5603914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lam, K.M.; Wang, Q. CoF-Net: A progressive coarse-to-fine framework for object detection in remote-sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5600617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Gao, E.; Han, C.; Guo, H.; Du, B.; Tao, D.; et al. MTP: Advancing remote sensing foundation model via multitask pretraining. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 11632–11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, H. Detection of ship targets in remote sensing image based on improved YOLOv5. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Science (EIECS), Changchun, China, 16–18 September 2022; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12602, pp. 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Luo, C.; Li, X.; Xiao, J. Rotating target detection algorithm in remote sensing images based on improved YOLOv5s. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL), Zhuhai, China, 12–14 May 2023; pp. 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, M.; Chala Urgessa, G.; Xing, M.; Han, L.; Chen, R. Toward more robust and real-time unmanned aerial vehicle detection and tracking via cross-scale feature aggregation based on the center keypoint. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yin, H.; Weng, L.; Xia, M.; Lin, H. DAFNet: A novel change-detection model for high-resolution remote-sensing imagery based on feature difference and attention mechanism. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yao, Y.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Dual-aligned oriented detector. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5618111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Lang, C.; Yao, Y.; Han, J. Anchor-free oriented proposal generator for object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5625411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhao, D.; Liu, S. Research on object detection in remote sensing images based on improved horizontal target detection algorithm. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Jing, N.; Jiang, J.; Guo, H.; Sheng, W.; Mao, Z.; Wang, Q. RTMDet-R2: An improved real-time rotated object detector. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV), Xiamen, China, 13–15 October 2023; pp. 352–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Su, A.; Teng, X.; Pan, E.; Liu, M.; Yu, Q. Oriented object detection in optical remote sensing images using deep learning: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wan, S.; Ma, X. Remote sensing image dense target detection based on rotating frame. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2006, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Lu, S.; Zhang, W. CAD-Net: A context-aware detection network for objects in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 10015–10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotto, L.; Cenedese, A.; Cavallaro, A. Active sensing for search and tracking: A review. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.02381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Qi, J. Research on remote sensing image target detection methods based on convolutional neural networks. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2025, 012068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method Category | Core Idea | Representative Models | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNN Methods | ||||

| Relational Inference | Model contextual dependencies by constructing topological graphs between objects. | RelaDet; GCN-based Detector | Strong for dense and occluded objects; enhanced contextual reasoning. | Requires predefined graph structures; potential over-smoothing. |

| Context-Aware Modeling | Capture multi-scale contextual cues using graph convolution or attention. | Contextual Graph Detector; Hierarchical GNN | Robust under complex backgrounds; suitable for large-scale RS scenes. | Lacks rotational invariance; may introduce angular inconsistency. |

| Hierarchical Graph Fusion | Fuse local and global information using multi-level graph structures. | PolyRoof; HNS-GNN | Improved multi-scale representation. | Cross-level noise propagation; insufficient refinement. |

| RL Methods | ||||

| Region Search | Model detection as a sequential decision process progressively focusing on candidate regions. | DeepRL-Detector; RLCNN | Efficient localization; reduced HR image computation. | Fixed search grids; action conflicts in dense scenes. |

| Rotation and Scale Adjustment | Learn actions that dynamically adjust bounding box orientation and scale. | FFPN-RL | Effective for multi-oriented, multi-scale objects. | Discrete actions cause error accumulation; slow convergence. |

| Policy Fusion and Optimization | Fuse multiple decision strategies to enhance adaptability and robustness. | Strategy Learning; HRL Saliency Model | Strong adaptability across scenes. | Depends on predefined modules; hierarchical feedback errors. |

| Method | Pre-Training | #P | FLOPs | FPS | mAP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetinaNet-O | IN | – | – | 23.0 | 57.55 |

| Faster RCNN-O | IN | 41.1 M | 198 G | 19.0 | 59.54 |

| TIOE-Det | IN | 41.1 M | 198 G | – | 61.98 |

| ARS-DETR | IN | 41.1 M | 198 G | 12 | 66.12 |

| O-RepPoints | IN | 36.6 M | – | 29 | 66.71 |

| DCFL | IN | – | – | 29 | 66.80 |

| LSKNet-S | IN | 31.0 M | 161 G | – | 65.90 |

| PKINet-S | IN | 30.8 M | 190 G | 5.2 | 67.03 |

| YOLOv5m-OBB (baseline) | IN | 21.2 M | 153 G | 62.3 | 63.40 |

| ASBPNet | CO | 22.1 M | 158 G | 61.1 | 68.10 |

| Method | Pre-Training | mAP (07) | mAP (12) | #P | FLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRN | IN | – | 92.70 | – | – | – |

| CenterMap | IN | – | 92.80 | 41.1 M | 198 G | – |

| RoI Trans. | IN | 86.20 | – | 55.1 M | 200G | 6.0 |

| G.V. | IN | 88.20 | – | 41.1 M | 198 G | – |

| R3Det | IN | 89.26 | 96.01 | 41.9 M | 336 G | 12.0 |

| DAL | IN | 89.77 | – | 36.4 M | 216 G | – |

| GWD | IN | 89.85 | 97.37 | 47.4 M | 456 G | – |

| S2ANet | IN | 90.17 | 95.01 | 38.6 M | 198 G | 14.3 |

| AOPG | IN | 90.34 | 96.22 | – | – | – |

| ReDet | IN | 90.46 | 97.63 | 31.6 M | – | 24.7 |

| O-RCNN | IN | 90.50 | 97.60 | 41.1 M | 199 G | 32.0 |

| RTMDet | CO | 90.60 | 97.10 | 52.3 M | 205 G | – |

| YOLOv5m-OBB (baseline) | IN | 88.50 | 96.80 | 21.2 M | 153 G | 62.6 |

| ASBPNet | CO | 90.60 | 98.20 | 22.1 M | 158 G | 61.7 |

| Method | mAP↑ | PL | BD | BR | GTF | SV | LV | SH | TC | BC | ST | SBF | RA | HA | SP | HC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Scale | ||||||||||||||||

| EMO2-DETR [47] | 70.91 | 87.99 | 79.46 | 45.74 | 66.64 | 78.90 | 73.90 | 73.30 | 90.40 | 80.55 | 85.89 | 55.19 | 63.62 | 51.83 | 70.15 | 60.04 |

| CenterMap [48] | 71.59 | 89.02 | 80.56 | 49.41 | 61.98 | 77.99 | 74.19 | 83.74 | 89.44 | 78.01 | 83.52 | 47.64 | 65.93 | 63.68 | 67.07 | 61.59 |

| AO2-DETR [49] | 72.15 | 86.01 | 75.92 | 46.02 | 66.65 | 79.70 | 79.93 | 89.17 | 90.44 | 81.19 | 76.00 | 56.91 | 62.45 | 64.22 | 65.80 | 58.96 |

| SCRDet [50] | 72.61 | 89.98 | 80.65 | 52.09 | 68.36 | 68.36 | 60.32 | 72.41 | 90.85 | 87.94 | 86.86 | 65.02 | 66.68 | 66.25 | 68.24 | 65.21 |

| R3Det [51] | 73.70 | 89.50 | 81.20 | 50.50 | 66.10 | 70.90 | 78.70 | 78.20 | 90.80 | 85.30 | 84.20 | 61.80 | 63.80 | 68.20 | 69.80 | 67.20 |

| RoI Trans. [52] | 74.05 | 89.01 | 77.48 | 51.64 | 72.07 | 74.43 | 77.55 | 87.76 | 90.81 | 79.71 | 85.27 | 58.36 | 64.11 | 76.50 | 71.99 | 54.06 |

| S2ANet [53] | 74.12 | 89.11 | 82.84 | 48.37 | 71.11 | 78.11 | 78.39 | 87.25 | 90.83 | 84.90 | 85.64 | 60.36 | 62.60 | 65.26 | 69.13 | 57.94 |

| SASM [54] | 74.92 | 86.42 | 78.97 | 52.47 | 69.84 | 77.30 | 75.99 | 86.72 | 90.89 | 82.63 | 85.66 | 60.13 | 68.25 | 73.98 | 72.22 | 62.37 |

| G.V. [55] | 75.02 | 89.64 | 85.00 | 52.26 | 77.34 | 73.01 | 73.14 | 86.82 | 90.74 | 79.02 | 86.81 | 59.55 | 70.91 | 72.94 | 70.86 | 57.32 |

| O-RCNN [56] | 75.87 | 89.46 | 82.12 | 54.78 | 70.86 | 78.93 | 83.00 | 88.20 | 90.90 | 87.50 | 84.68 | 63.97 | 67.69 | 74.64 | 84.93 | 52.28 |

| ReDet [57] | 76.25 | 88.79 | 82.64 | 53.97 | 74.00 | 78.13 | 84.06 | 88.04 | 90.89 | 87.78 | 85.75 | 61.76 | 60.39 | 75.96 | 68.07 | 63.59 |

| R3Det-GWD [58] | 76.34 | 88.82 | 82.94 | 55.63 | 72.75 | 78.52 | 83.10 | 87.46 | 90.21 | 86.36 | 85.44 | 64.70 | 61.41 | 73.46 | 76.94 | 57.38 |

| R3Det-KLD [59] | 77.36 | 88.90 | 84.17 | 55.80 | 69.35 | 78.72 | 84.08 | 87.00 | 89.75 | 84.32 | 85.73 | 64.74 | 61.80 | 76.62 | 78.49 | 70.89 |

| ARC [60] | 77.35 | 89.40 | 82.48 | 55.33 | 73.88 | 79.37 | 84.05 | 88.06 | 90.90 | 86.44 | 84.83 | 63.63 | 70.32 | 74.29 | 71.91 | 65.43 |

| LSKNet-S [61] | 77.49 | 89.66 | 85.52 | 57.72 | 75.70 | 74.95 | 78.69 | 88.24 | 90.88 | 86.79 | 86.38 | 66.92 | 63.77 | 77.77 | 74.47 | 64.82 |

| PKINet-S [62] | 78.39 | 89.72 | 84.20 | 55.81 | 77.63 | 80.25 | 84.45 | 88.12 | 90.88 | 87.57 | 86.07 | 66.86 | 70.23 | 77.47 | 73.62 | 62.94 |

| O2DNet [63] | 71.01 | 89.36 | 82.18 | 47.31 | 61.24 | 71.33 | 74.02 | 78.64 | 90.81 | 82.23 | 81.42 | 60.90 | 60.22 | 58.21 | 67.02 | 61.04 |

| CFC-Net [64] | 73.52 | 89.13 | 80.44 | 52.41 | 70.04 | 76.31 | 78.14 | 87.23 | 90.92 | 84.54 | 85.61 | 60.51 | 61.53 | 67.82 | 68.01 | 50.15 |

| CBDA-Net [65] | 75.74 | 89.24 | 85.94 | 50.32 | 65.01 | 77.71 | 82.33 | 87.93 | 90.52 | 86.51 | 85.90 | 66.92 | 66.51 | 67.43 | 71.32 | 62.91 |

| CoF-Net [66] | 77.21 | 89.60 | 83.12 | 48.31 | 73.64 | 78.23 | 83.04 | 86.72 | 90.24 | 82.32 | 86.61 | 67.61 | 64.63 | 74.70 | 71.32 | 78.42 |

| MTP [67] | 79.03 | 89.87 | 85.09 | 58.27 | 71.70 | 81.70 | 87.10 | 88.98 | 91.44 | 85.41 | 86.45 | 57.44 | 68.47 | 78.42 | 82.97 | 71.71 |

| YOLOv5m-OBB (baseline) [68] | 77.30 | 89.90 | 81.50 | 58.80 | 75.50 | 76.90 | 79.30 | 81.30 | 89.70 | 83.00 | 87.10 | 67.10 | 72.00 | 79.50 | 77.00 | 60.90 |

| ASBPNet | 79.60 | 91.50 | 83.00 | 64.40 | 77.70 | 80.80 | 81.30 | 83.10 | 90.90 | 84.60 | 89.10 | 69.10 | 73.90 | 81.00 | 78.70 | 64.90 |

| Multi-Scale | ||||||||||||||||

| CSL [69] | 76.17 | 90.25 | 85.53 | 54.64 | 75.31 | 70.44 | 73.51 | 77.62 | 90.84 | 86.15 | 86.69 | 69.60 | 68.04 | 73.83 | 71.10 | 68.93 |

| CFA [70] | 76.67 | 89.08 | 83.20 | 54.37 | 66.87 | 81.23 | 80.96 | 87.17 | 90.21 | 84.32 | 86.09 | 52.34 | 69.94 | 75.52 | 80.76 | 67.96 |

| DAFNeT [71] | 76.95 | 89.40 | 86.27 | 53.70 | 60.51 | 82.04 | 81.17 | 88.66 | 90.37 | 83.81 | 87.27 | 53.93 | 69.38 | 75.61 | 81.26 | 70.86 |

| DODet [72] | 80.62 | 89.96 | 85.52 | 58.01 | 81.22 | 78.71 | 85.46 | 88.59 | 90.89 | 87.12 | 87.80 | 70.50 | 71.54 | 82.06 | 77.43 | 74.47 |

| AOPG [73] | 80.66 | 89.88 | 85.57 | 60.90 | 81.51 | 78.70 | 85.29 | 88.85 | 90.89 | 87.60 | 87.65 | 71.66 | 68.69 | 82.31 | 77.32 | 73.10 |

| KFIoU [74] | 80.93 | 89.44 | 84.41 | 62.22 | 82.51 | 80.10 | 86.07 | 88.68 | 90.90 | 87.32 | 88.38 | 72.80 | 71.95 | 78.96 | 74.95 | 75.27 |

| RTMDet-RKFIoU [75] | 81.33 | 88.01 | 86.17 | 58.54 | 82.44 | 81.30 | 84.82 | 88.71 | 90.89 | 88.77 | 87.37 | 71.96 | 71.18 | 81.23 | 81.40 | 77.13 |

| Multi-Scale | ||||||||||||||||

| RVSA [76] | 81.24 | 88.97 | 85.76 | 61.46 | 81.27 | 79.98 | 85.31 | 88.30 | 90.84 | 85.06 | 87.50 | 66.77 | 73.11 | 84.75 | 81.88 | 77.58 |

| LSKNet-S [61] | 81.64 | 89.57 | 86.34 | 63.13 | 83.67 | 82.20 | 86.10 | 88.66 | 90.89 | 88.41 | 87.42 | 71.72 | 69.58 | 78.88 | 81.77 | 76.52 |

| FR-O [77] | 54.11 | 79.42 | 77.13 | 17.72 | 64.14 | 35.32 | 38.01 | 37.26 | 89.43 | 69.62 | 59.34 | 50.30 | 52.93 | 47.91 | 47.43 | 46.31 |

| CAD-Net [78] | 69.96 | 87.82 | 82.41 | 49.43 | 73.51 | 71.13 | 63.52 | 76.62 | 90.91 | 79.23 | 73.33 | 48.44 | 60.92 | 62.03 | 67.01 | 62.24 |

| APE [79] | 75.81 | 90.01 | 83.65 | 53.43 | 76.02 | 74.01 | 77.27 | 79.53 | 90.82 | 87.27 | 84.51 | 67.72 | 60.31 | 74.60 | 71.84 | 65.62 |

| SCRDet [80] | 72.63 | 90.01 | 80.71 | 52.14 | 68.43 | 68.42 | 60.32 | 72.44 | 90.92 | 87.94 | 86.96 | 65.02 | 66.73 | 66.31 | 68.23 | 65.21 |

| YOLOv5m-OBB (baseline) | 80.20 | 92.50 | 84.00 | 61.50 | 78.50 | 80.50 | 82.00 | 84.50 | 93.00 | 86.00 | 90.50 | 70.00 | 74.00 | 82.00 | 79.00 | 65.00 |

| ASBPNet | 81.50 | 93.40 | 84.90 | 64.10 | 79.90 | 82.30 | 83.20 | 85.60 | 93.30 | 86.80 | 91.50 | 71.80 | 75.30 | 82.90 | 79.90 | 67.60 |

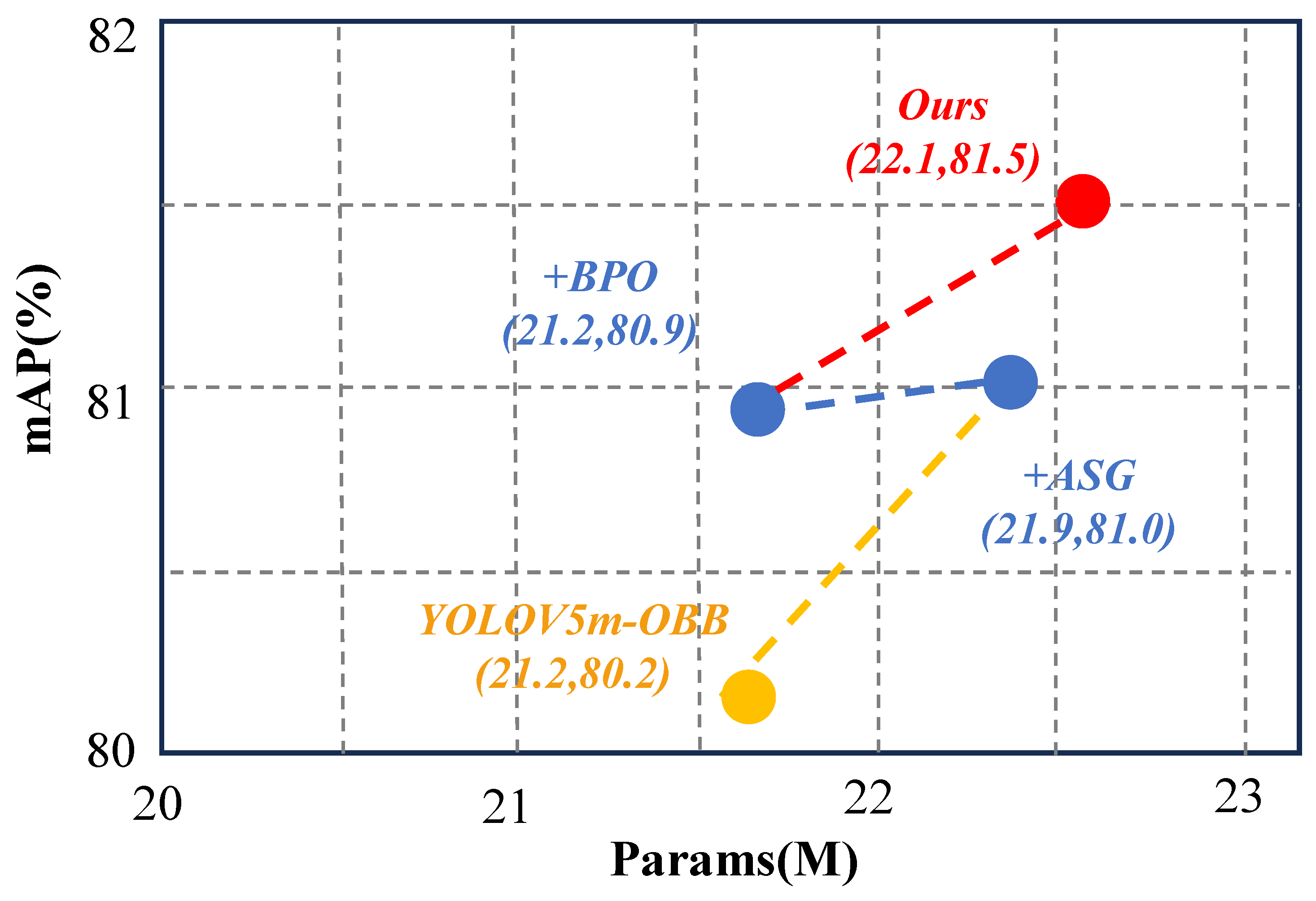

| Setting | Description | mAP | ΔmAP | #Params | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | YOLOv5m-OBB | 80.20 | – | 21.2 M | 153 |

| B | +ASG | 81.00 | +0.80 | 21.9 M | 156 |

| C | +BPO | 80.90 | +0.70 | 21.2 M | 153 |

| D | ASG + BPO (Ours) | 81.50 | +1.30 | 22.1 M | 158 |

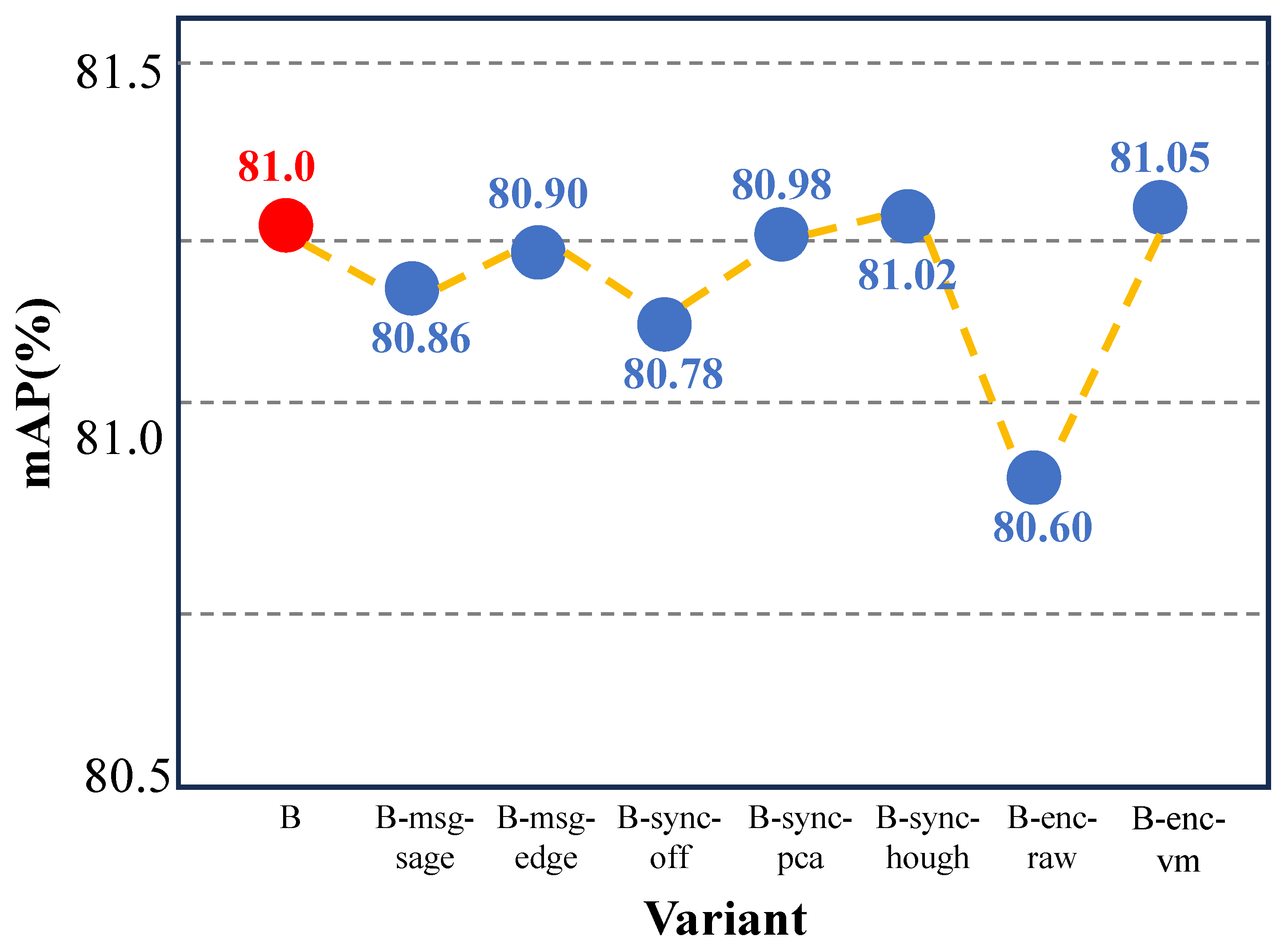

| Variant | Description | mAP |

|---|---|---|

| B (default) | GATv2 message + SE(2) equivariant alignment + Angle Sync | 81.00 |

| B-msg-sage | GraphSAGE message passing | 80.86 |

| B-msg-edge | EdgeConv-style message passing | 80.90 |

| B-sync-off | Disable Angle Sync regularization | 80.78 |

| B-sync-pca | Sync prior: local PCA principal direction | 80.98 |

| B-sync-hough | Sync prior: Hough line direction | 81.02 |

| B-enc-rawθ | Angle encoding: raw (no sin/cos) | 80.60 |

| B-enc-vm | Angle encoding: sin/cos + von Mises embedding | 81.05 |

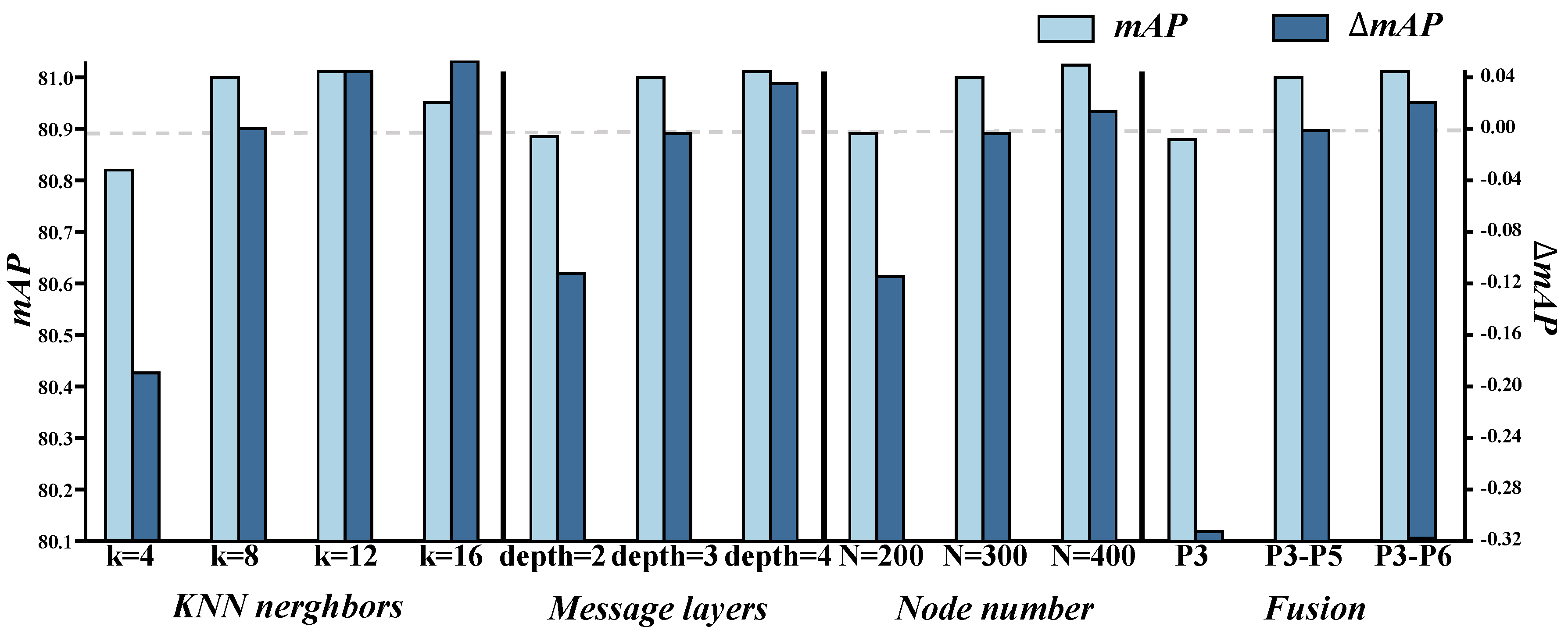

| Variant | Configuration | mAP | ΔmAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| k-4 | kNN neighbors | 80.82 | −0.18 |

| k-8 (default) | 81.00 | – | |

| k-12 | 81.04 | +0.04 | |

| k-16 | 80.95 | −0.05 | |

| depth-2 | Message layers = 2 | 80.89 | −0.11 |

| depth-3 (default) | Message layers = 3 | 81.00 | – |

| depth-4 | Message layers = 4 | 81.03 | +0.03 |

| TopN-200 | Node number | 80.90 | −0.10 |

| TopN-300 (default) | 81.00 | – | |

| TopN-400 | 81.01 | +0.01 | |

| P3-only | P3 RoI only | 80.70 | −0.30 |

| P3–P5 (default) | Fusion of P3–P5 | 81.00 | – |

| P3–P6 | Fusion of P3–P6 | 81.02 | +0.02 |

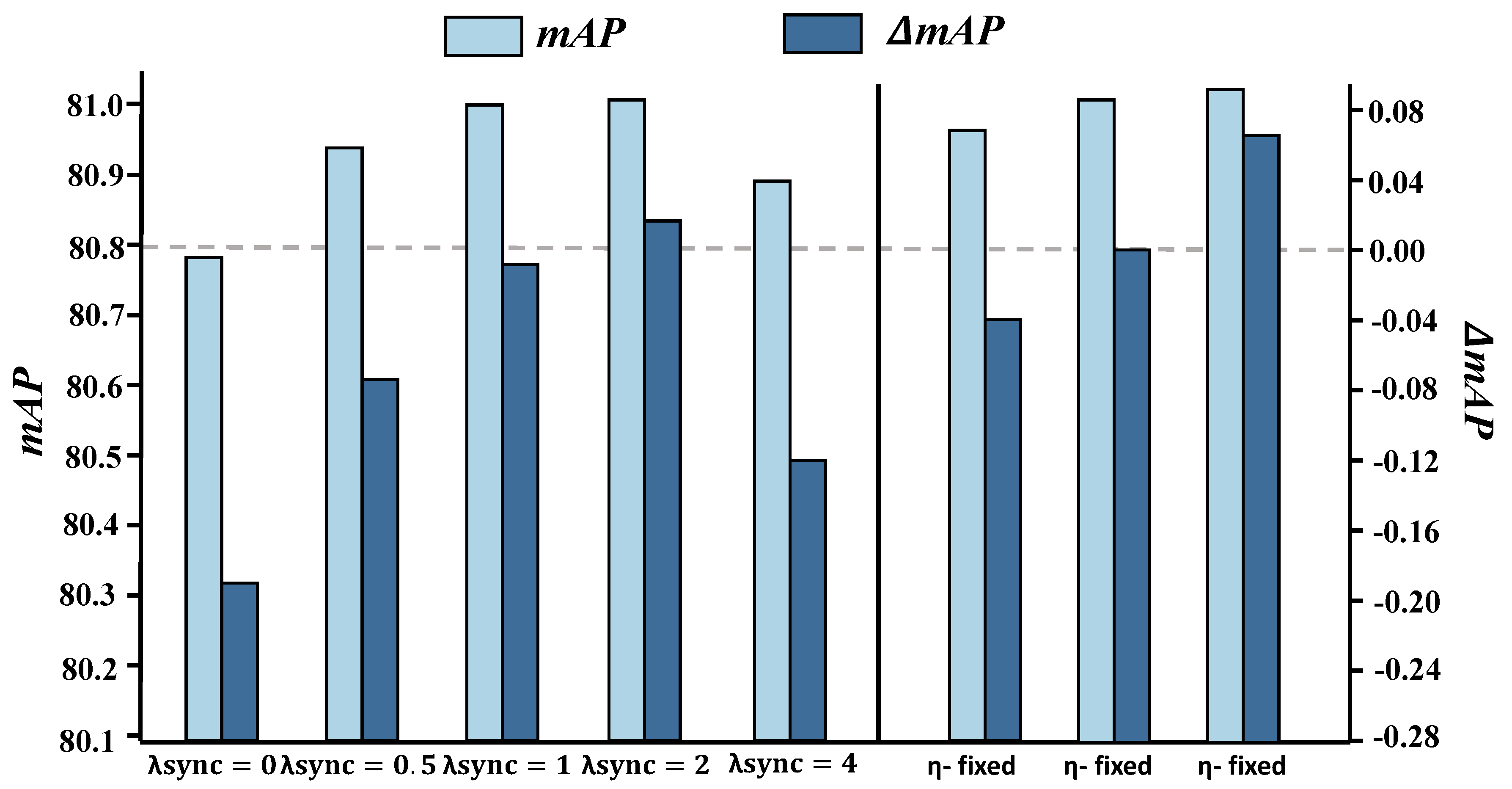

| Variant | Configuration | mAP | ΔmAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remove synchronization term | 80.78 | −0.22 | |

| Sync weight = 0.5 | 80.94 | −0.06 | |

| (default) | Default sync weight | 81.00 | – |

| Sync weight = 2.0 | 81.02 | +0.02 | |

| Sync weight = 4.0 | 80.88 | −0.12 | |

| -fixed | Fixed step size | 80.96 | −0.04 |

| -learn (default) | Lightweight MLP predicts | 81.00 | – |

| -linesearch | Line-search single-step backtracking | 81.06 | +0.06 |

| Variant | Action Space | mAP | Latency Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 R-Aug only | Learn rotation augmentation angle distribution | 80.56 | 0% |

| C2 DNMS only | Learn rNMS threshold (class/scale adaptive) | 80.48 | 0% |

| C3 AMTS only | Learn slice size/stride/overlap/rotation | 80.42 | +4% |

| C4 DPA only | Learn rIoU positive/negative thresholds | 80.32 | 0% |

| C (default) | R-Aug + DNMS + AMTS (with budget) | 80.90 | +2% |

| Small | Medium | Large | mAP | ΔmAP | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 80.72 | −0.18 | 0% |

| 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.55 (default) | 80.90 | – | +2% |

| 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 81.00 | +0.10 | +2% |

| 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 80.84 | −0.06 | +2% |

| Tile/Stride/Overlap/Rotation | mAP | ΔmAP | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 768/256/33%/ON | 80.96 | +0.06 | +6% |

| 1024/384/25%/ON (default) | 80.90 | – | +2% |

| 1024/384/25%/OFF | 80.85 | −0.05 | +1% |

| 1280/512/20%/ON | 80.88 | −0.02 | −3% |

| Distribution | Angle/Probability Scheme | mAP | ΔmAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform | 80.82 | −0.08 | |

| Bimodal | High weights at / | 81.02 | +0.12 |

| Tri-modal (default) | Mix of , , and uniform | 80.90 | – |

| (IoUpos, IoUneg) | mAP | ΔmAP |

|---|---|---|

| (0.4, 0.2) | 80.60 | −0.30 |

| (0.5, 0.3) (default) | 80.90 | – |

| (0.6, 0.3) | 80.96 | +0.06 |

| (0.6, 0.4) | 80.88 | −0.02 |

| Hyperparameter | Setting | mAP | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | PPO (default) | 80.90 | +2% |

| SAC | 80.88 | +2% | |

| Budget B | 10.0 ms | 80.70 | ≤10 ms |

| 12.5 ms (default) | 80.90 | ≤12.5 ms | |

| 15.0 ms | 81.05 | ≤15 ms | |

| Small-object weight | 0.0 | 80.78 | +1% |

| 0.2 (default) | 80.90 | +2% | |

| 0.5 | 81.00 | +3% | |

| AP surrogate | 0.05 | 80.82 | +2% |

| 0.10 (default) | 80.90 | +2% | |

| 0.20 | 80.84 | +2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, J.; Liu, J.; Tang, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y. From Graph Synchronization to Policy Learning: Angle-Synchronized Graph and Bilevel Policy Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244029

Yan J, Liu J, Tang L, Wang X, Guo Y. From Graph Synchronization to Policy Learning: Angle-Synchronized Graph and Bilevel Policy Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244029

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Jie, Jialang Liu, Lixing Tang, Xiaoxiang Wang, and Yanming Guo. 2025. "From Graph Synchronization to Policy Learning: Angle-Synchronized Graph and Bilevel Policy Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244029

APA StyleYan, J., Liu, J., Tang, L., Wang, X., & Guo, Y. (2025). From Graph Synchronization to Policy Learning: Angle-Synchronized Graph and Bilevel Policy Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244029