1. Introduction

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) captures data across numerous adjacent spectral channels, offering exceptional spectral discrimination and rich information. This capability supports applications in precision agriculture [

1], environmental surveillance [

2], resource exploration [

3], urban development [

4], and medical diagnostics [

5,

6]. HSIs excel in target detection, scene classification, and temporal change analysis in remote sensing [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, their high dimensionality poses challenges such as redundancy, overlapping spectra, and increased computational demands [

11]. Besides spectral data, spatial structure is crucial, but traditional methods often treat spectral and spatial features separately, missing their combined potential [

12,

13]. Therefore, effectively mixing spatial and spectral information to enhance feature representation, classification accuracy, and model generalization remains a key challenge [

14,

15].

Recently, significant advancements in machine learning and deep learning have paved the way for more effective methods in hyperspectral image classification (HIC) [

16]. Earlier research primarily employed traditional classifiers that depended on manually designed feature extraction processes, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

17], Random Forests [

18], and multinomial logistic regression techniques [

19,

20]. These approaches demonstrated reasonable performance on smaller datasets; however, their effectiveness is compromised when encountering the complex, high-dimensional characteristics inherent to hyperspectral imagery. Conventional models typically exhibit limitations in acquiring profound and abstract feature representations—a necessity for high classification accuracy in complex scenarios [

21]. Recent studies have also addressed more advanced challenges, such as open-set and zero-shot classification. For instance, an open-set classification method for hyperspectral images has been proposed to improve the ability to recognize unseen categories [

22]. Similarly, a zero-shot Mars scene classification framework was introduced, addressing the lack of labeled data through knowledge distillation techniques [

23].

Deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has become a leading method for joint spectral–spatial feature extraction in HSI analysis [

24,

25]. For example, Hu et al. developed a 1D-CNN to capture spectral features [

26], while Yu et al. designed a deep 2D-CNN with deconvolutional layers to better model spatial–spectral correlations [

27]. Similarly, Joshi et al. combined wavelet transforms with 2D-CNN to enhance spatial feature extraction [

28]. Zhang et al. proposed a hybrid model integrating 1D and 2D CNNs with specialized convolution modules for spatial and spectral domains [

29]. In another article, Zhang et al. introduced an improved 3D-Inception network using multi-scale 3D convolutions and adaptive band selection [

30]. Roy et al.’s HybridSN fused 2D-CNN and 3D-CNN to jointly capture spectral and spatial features, demonstrating the strength of hybrid convolutions [

31]. Despite CNNs’ success in learning local patterns, their fixed receptive fields and sequential layers limit capturing global context, which can reduce classification accuracy [

32].

Contemporary research has witnessed the remarkable success of Transformer architectures, initially developed with self-attention operations, across diverse visual and linguistic processing applications [

33,

34]. Dosovitskiy et al. presented the Vision Transformer (ViT), which models global contextual relationships in conventional imagery and exhibits robust capabilities in visual recognition tasks [

35]. In contrast to CNNs, which are constrained by localized receptive regions, Transformer architectures leverage self-attention mechanisms to establish comprehensive feature correlations, enabling more effective extraction of extended contextual relationships [

36]. This strength has led to a growing interest in applying Transformer-based architectures to HIC [

37,

38]. For instance, Yang et al. developed a hierarchical spectral–spatial Transformer architecture built on an encoder–decoder framework, which effectively integrates spectral and spatial information and demonstrates competitive classification results [

39]. Similarly, Zou et al. designed the Locally Enhanced Spectral–Spatial Transformer (LESSFormer) to address CNNs’ limitations in modeling non-local dependencies [

40]. Zhang et al. further developed the Spectral–Spatial Center-Aware Bottleneck Transformer (S2CABT), a novel architecture that enhances classification accuracy through targeted attention to spectrally and spatially homogeneous neighboring pixels relative to the central reference pixel [

41]. Despite these advantages, applying Transformers to hyperspectral data introduces several challenges [

42,

43]. Standard Transformers, when applied directly to hyperspectral imagery, may insufficiently capture spatial information because of their inherently sequential design. Furthermore, their large number of parameters and dependence on extensive labeled data often lead to overfitting in hyperspectral scenarios where annotated samples are limited.

These limitations indicate that existing approaches, though powerful, still struggle to balance spectral–spatial representation quality, robustness, and computational efficiency. Convolutional networks excel at extracting fine-grained local features but lack global context awareness, whereas Transformers provide global dependency modeling but tend to overlook local texture and structure when data are scarce. Consequently, a unified framework that can effectively integrate CNNs’ local feature learning and Transformers’ global contextual modeling is still needed for practical hyperspectral image classification. To overcome CNNs’ limited global context capture and Transformers’ spatial modeling inefficiencies and high computational cost, hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures have emerged. These combine CNNs’ fine-grained local feature extraction with Transformers’ long-range dependency modeling to improve classification accuracy [

44,

45]. For example, Yang et al. presented Hyperspectral image Transformer (HiT), embedding convolutional layers within a Transformer to jointly leverage spectral and spatial cues, addressing CNNs’ spectral sequence modeling gaps [

46]. Zhang et al.’s TransHSI merges 3D-CNN, 2D-CNN, and Transformer modules for comprehensive spectral–spatial feature learning [

47]. Chen et al. developed a CNN–Transformer network with pooled attention fusion to reduce inter-layer information loss and enhance spatial feature learning [

48]. Wang et al. suggested Transformer Hybrid Network (CTHN), integrating multi-scale convolutions with self-attention to capture local patterns and global context simultaneously [

49]. Zhang et al. established a deeply aggregated convolutional Transformer architecture that combines CNNs’ local extraction with ViTs’ global representation, boosting classification accuracy [

50]. Despite these advances, several limitations in current hybrid methods remain:

(1) Insufficient spectral–spatial feature fusion: Some methods lack effective fusion strategies when integrating local and global features, resulting in inadequate complementarity between spectral and spatial information.

(2) Limited multi-scale feature extraction: Hyperspectral imagery exhibits significant scale variations, rich textural characteristics, and complex spatial structures among ground objects. The multi-scale information, shallow texture features, and deep structural patterns are all critical for accurate classification. However, most existing methods rely solely on single-scale or single-level features, which significantly constrain their capability to effectively extract multi-scale textural and structural information of ground objects.

(3) Inter-layer feature information loss: In HIC tasks, deep networks typically employ hierarchical feature extraction to obtain more discriminative representations. However, certain network architectures suffer from gradient vanishing, information attenuation, or feature redundancy during deep feature extraction and information propagation. These issues prevent the effective transmission of critical features to subsequent layers, thereby compromising the model’s representational capacity for hyperspectral data.

Thus, successfully merging CNNs’ local receptive field strengths with Transformers’ global context modeling remains a key challenge in hyperspectral classification [

51]. Other enhanced approaches, such as APA-boosted networks and similar ensemble-based frameworks, have also been applied to hyperspectral image classification. However, these methods mainly focus on improving decision-level outcomes through iterative reweighting or aggregation strategies, which often increase computational cost and training complexity. In contrast, STM-Net is designed to strengthen spectral–spatial representation at the feature level by combining convolutional and attention mechanisms within a unified architecture, thereby achieving more effective and efficient classification. To address this, we propose STM-Net, a novel hybrid architecture that unifies CNN-enabled local feature representation with Transformer-facilitated global context modeling to optimize classification accuracy. First, 3D convolutions with residual connections are employed by STM-Net’s CNN-based Spectral–Spatial Residual Extractor (SSRE) to capture multi-scale spectral features and deepen spectral representations. Second, 2D differential convolutions and CBAM attention are used by the Multi-scale Differential Residual Module (MDRM) to enhance local spatial feature extraction, improving edge and texture perception. Finally, standard self-attention for global context is combined with 1D convolutional attention by DBGL to strengthen local spatial modeling. This integrated design significantly improves spectral–spatial feature learning and classification performance. The significant contributions of this research are as follows:

(1) STM-Net is presented as an innovative hybrid architecture that synergistically integrates CNN and Transformer to enhance HIC. In this framework, the local spectral–spatial feature learning capacity of CNNs is seamlessly combined with the global modeling strength of the Transformer, resulting in superior classification performance on hyperspectral remote sensing data.

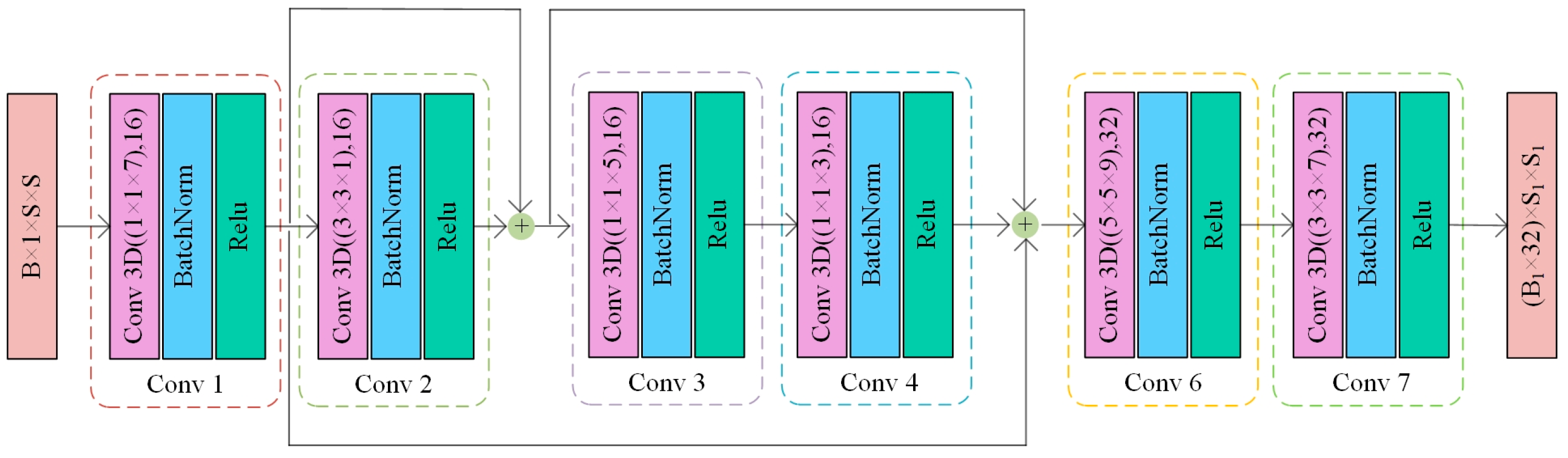

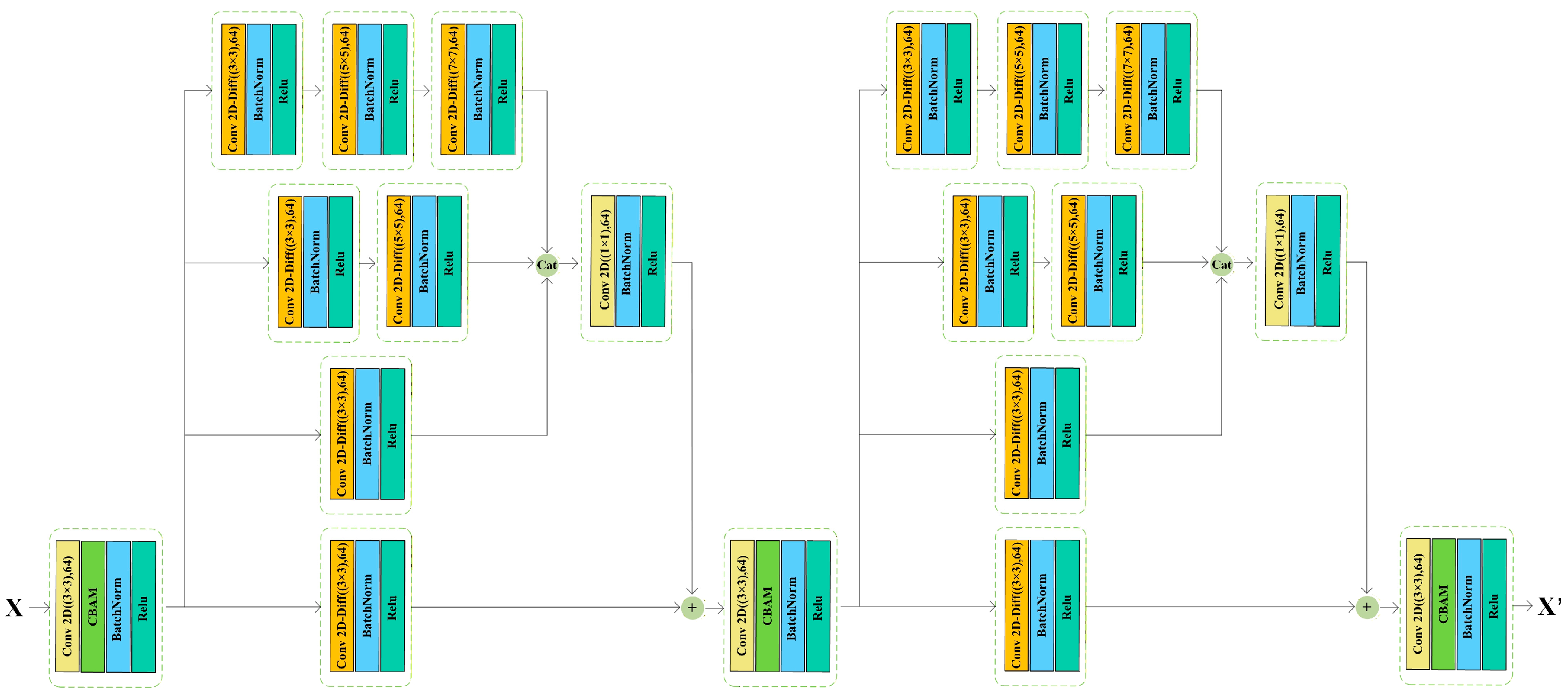

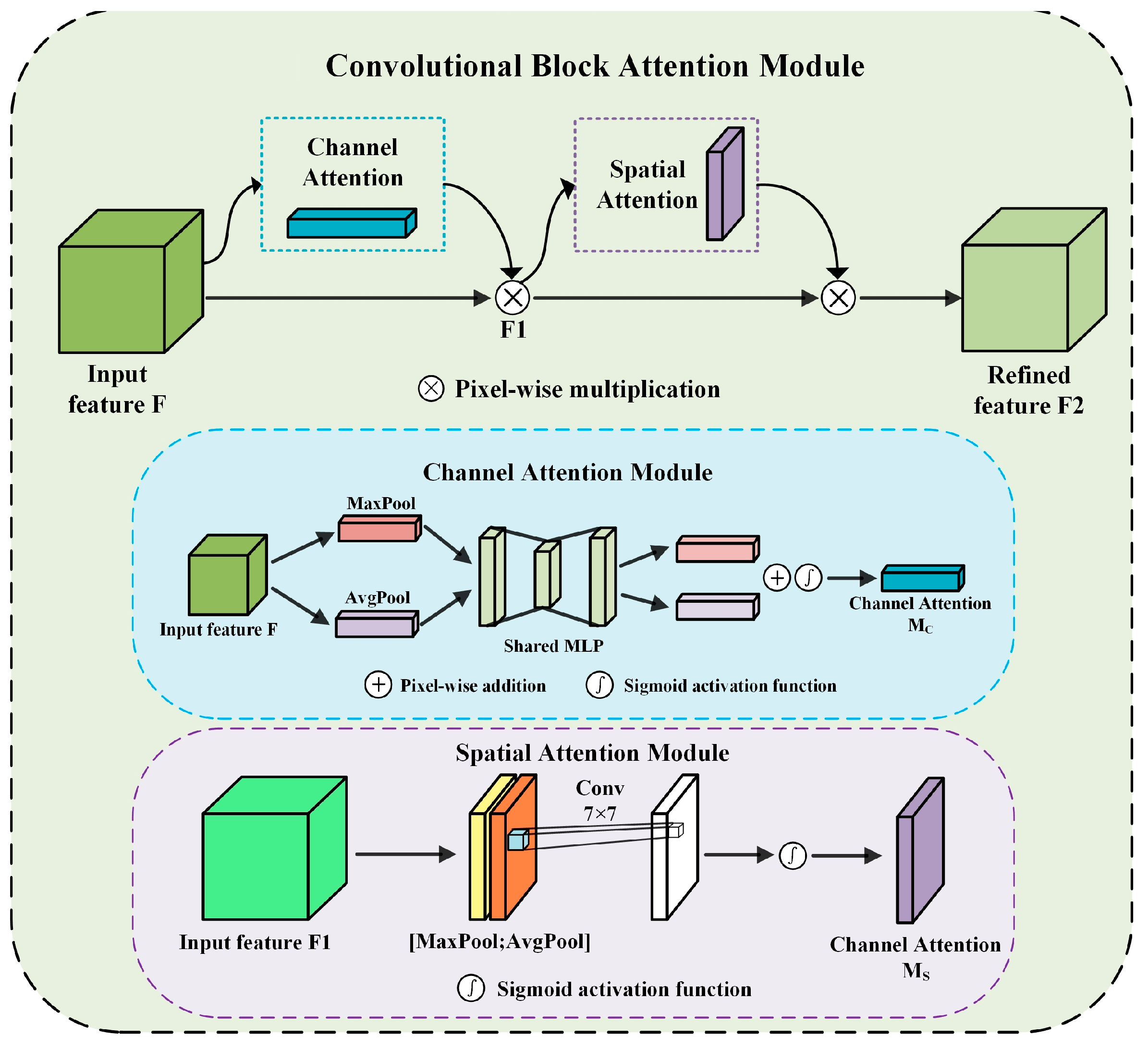

(2) An SSRE and an MDRM were designed. The SSRE module employs 3D convolutions with residual connections to enhance spectral–spatial feature extraction, while the MDRM block combines 2D differential convolutions with CBAM attention mechanisms to improve spatial feature discrimination. These integrated modules function cooperatively to strengthen the model’s discriminative power for land-cover categories with analogous spectral characteristics.

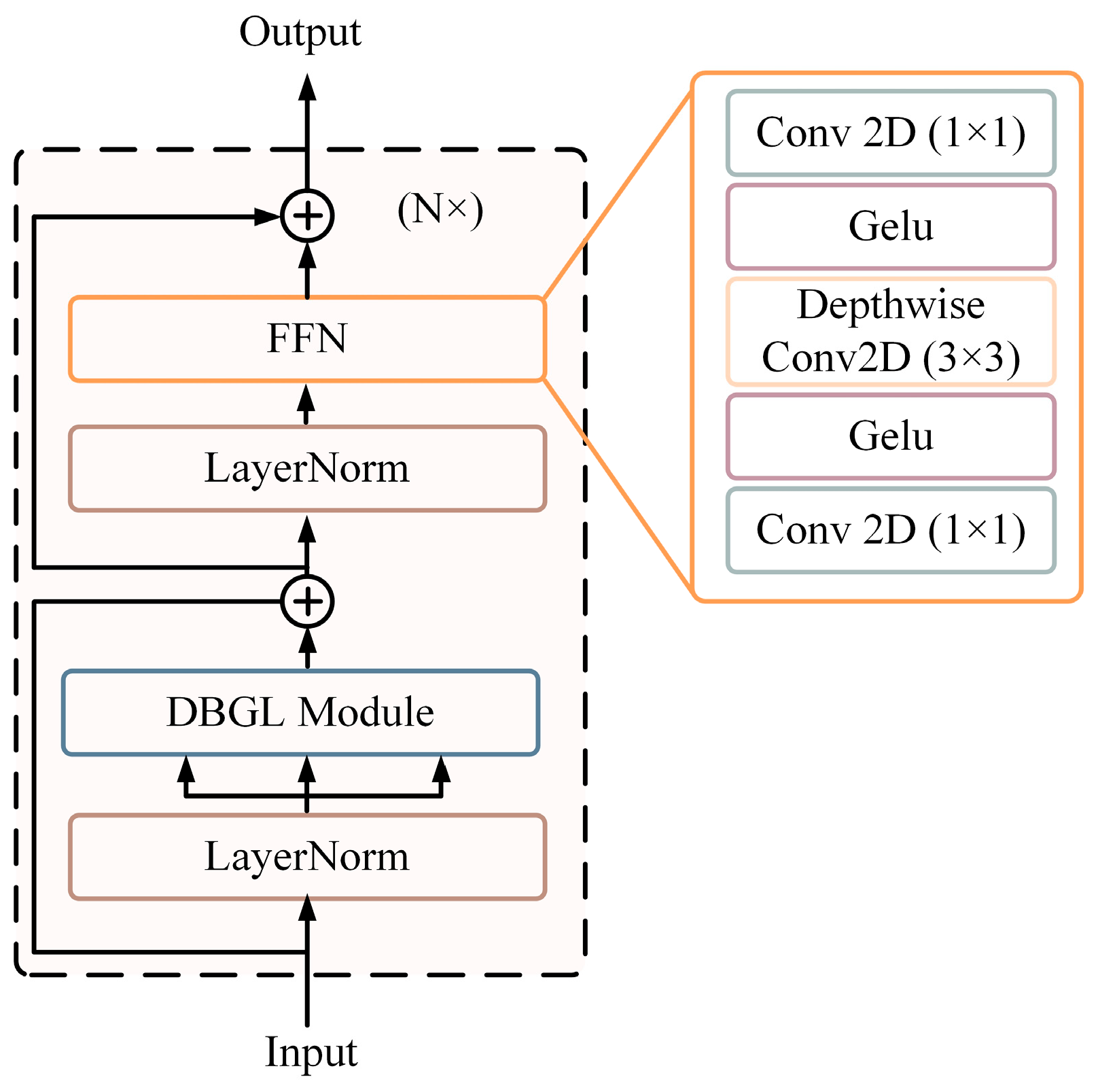

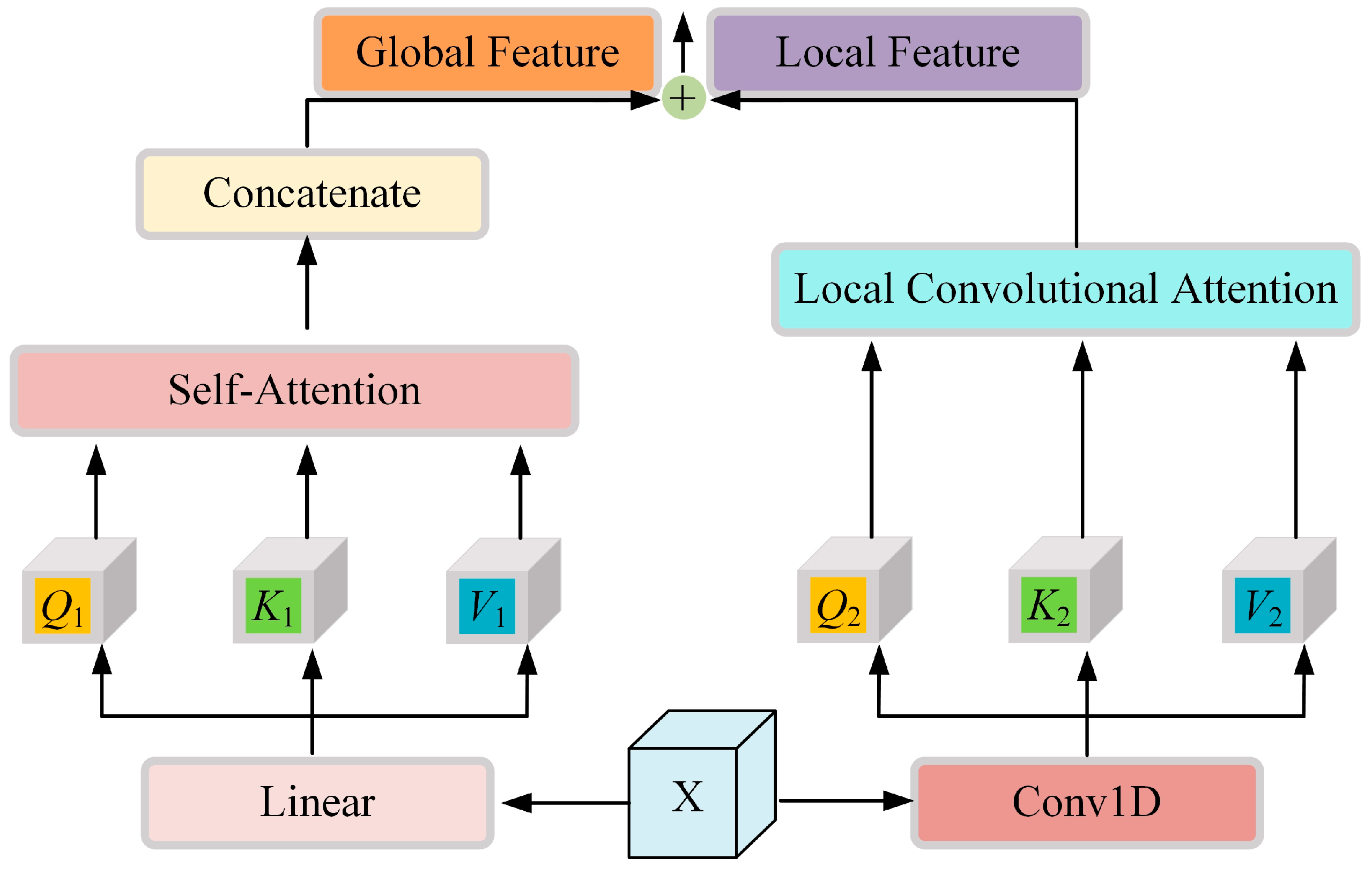

(3) An enhanced Transformer attention mechanism DBGL is proposed, integrating standard self-attention with local convolutional attention. This enables concurrent modeling of long-range dependencies and fine-grained local patterns, enhancing model robustness and generalization performance.

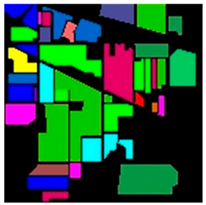

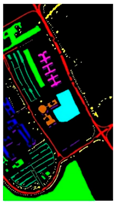

(4) The proposed method is rigorously assessed on 3 widely employed public benchmark datasets. Experimental outcomes suggest that STM-Net consistently outperforms existing state-of-the-art approaches in classification accuracy. Additionally, systematic component-wise analyses confirm the individual contribution of each network module to the overall performance.

This paper is arranged as follows.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive description of the suggested methodology, detailing the architecture and key components of our model.

Section 3 systematically reports experimental findings across three benchmark datasets, including comparative analyses with state-of-the-art techniques.

Section 5 summarizes key contributions and outlines promising avenues for future investigation.

4. Discussion

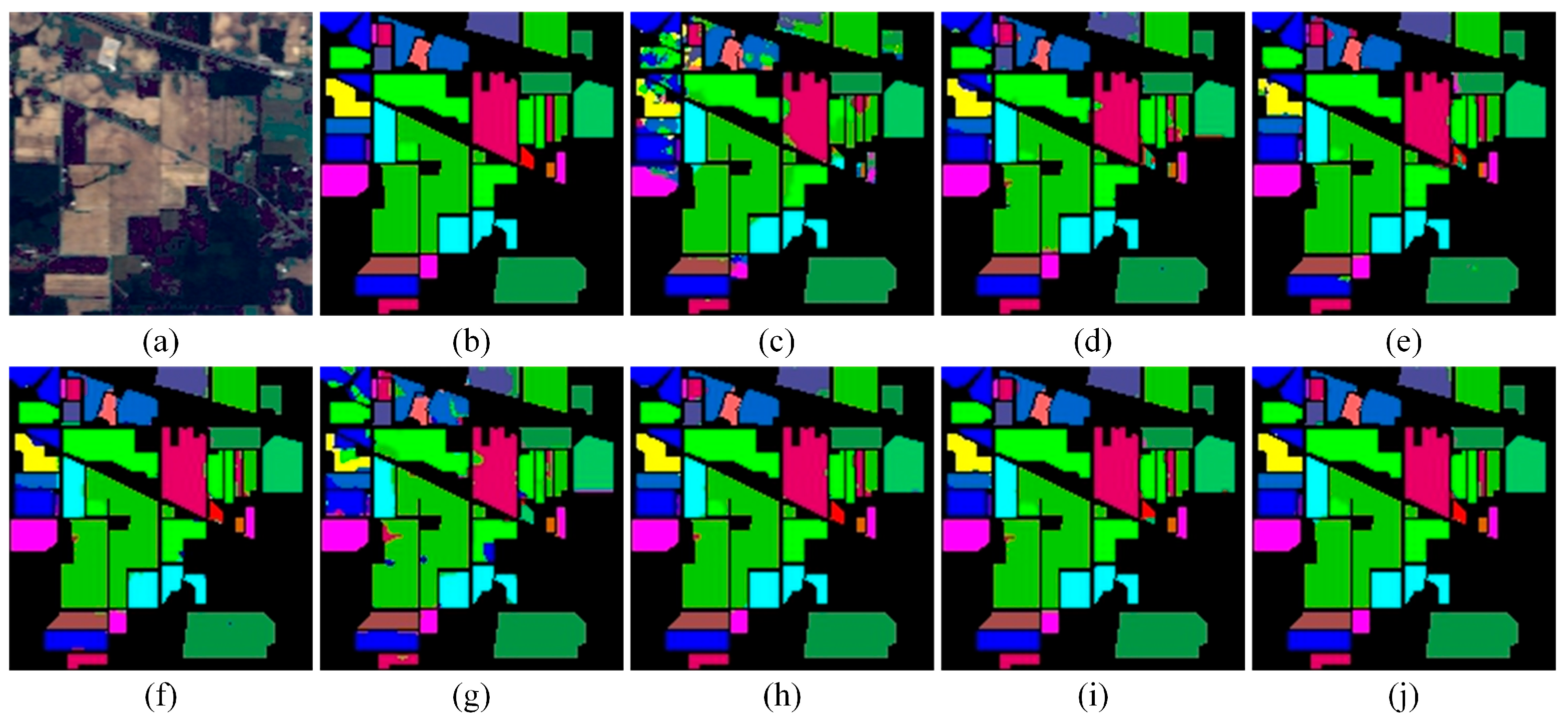

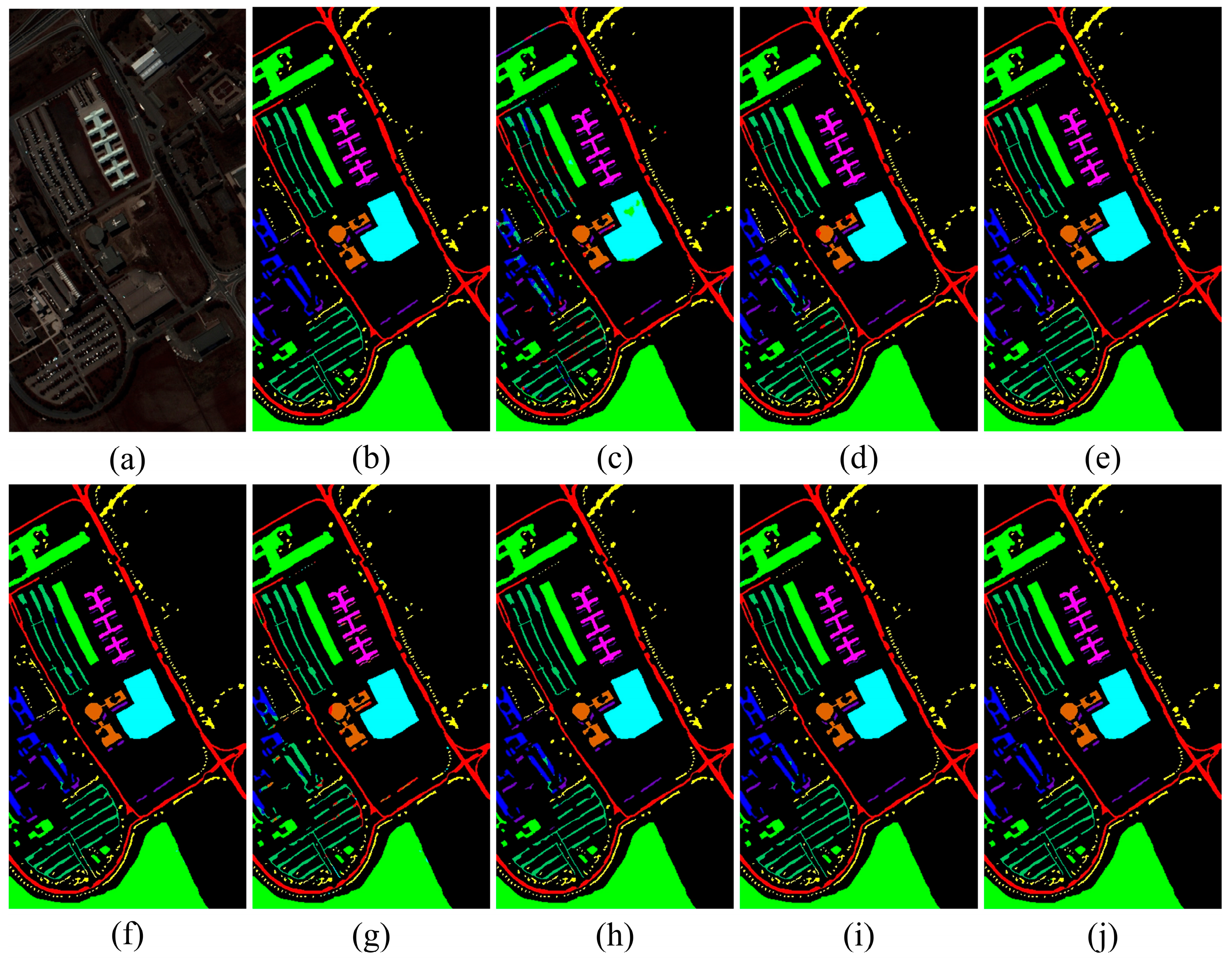

The experimental results demonstrate that STM-Net provides a more expressive and balanced representation of spectral–spatial information than competing approaches. The SSRE module plays a central role in this improvement. By employing multi-scale 3D convolutions with residual connections, SSRE captures informative spectral–spatial cues while reducing redundancy. The noticeable accuracy drop observed in its ablation verifies its importance in stabilizing feature extraction, especially under limited training samples.

Traditional CNN-based classifiers generally emphasize local texture and edge patterns but struggle to model long-range context, which is essential in hyperspectral imagery that often contains mixed pixels and spectrally similar categories. The incorporation of the DBGL mechanism addresses this limitation. Through the joint use of global self-attention and local convolutional attention, the Transformer branch becomes capable of capturing extended contextual relationships without sacrificing sensitivity to fine structural variations. The performance gains observed in boundary regions and minority classes further highlight the value of this global–local fusion strategy.

The MDRM also contributes substantially to the robustness of STM-Net. Its multi-scale differential convolutions, combined with CBAM attention, strengthen local contrast representation and texture discrimination. When either the multi-scale structure or the differential component is removed, the model exhibits a clear decline in accuracy, which underscores the importance of enhancing spatial detail for complex hyperspectral scenes.

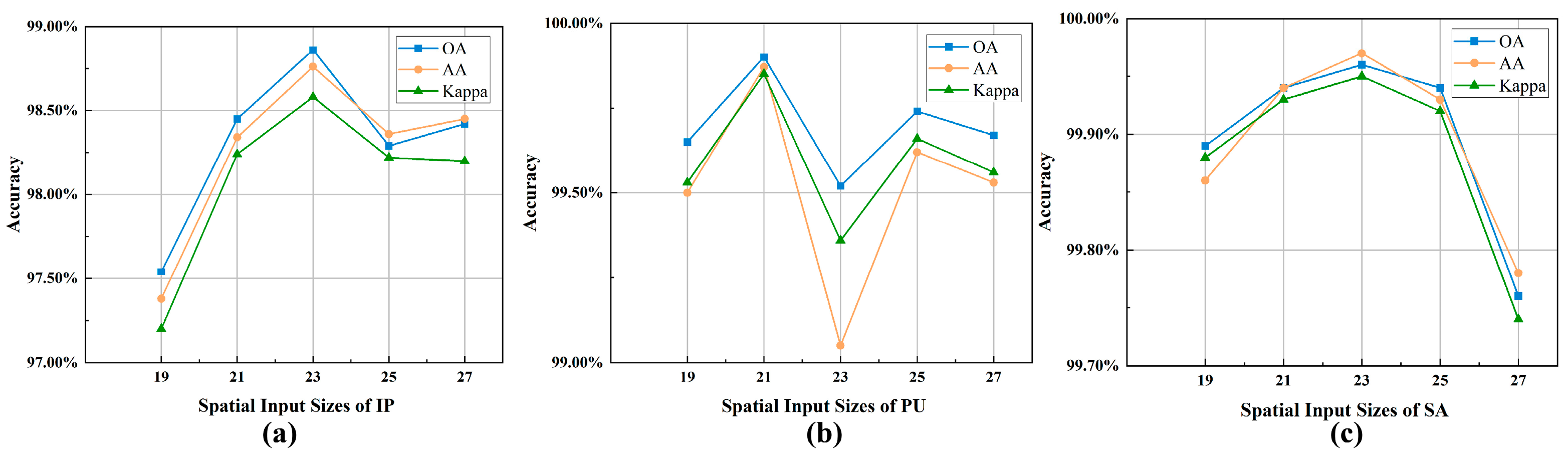

The analysis of hyperparameters provides additional insights. Both PCA channel numbers and spatial window sizes exhibit dataset-dependent optimal values. Excessive spectral dimensions introduce redundant information, whereas overly small dimensions weaken class separability. Similarly, spatial windows must balance contextual completeness and noise suppression. These findings indicate that STM-Net benefits from a tailored configuration that corresponds to scene characteristics.

In summary, STM-Net achieves a strong balance between local feature extraction and global dependency modeling, while maintaining a manageable computational cost. Although the architecture is more complex than lightweight CNNs, it remains efficient enough for most remote sensing applications. Future research may incorporate model compression, semi-supervised or self-supervised strategies, and multimodal data fusion to further enhance adaptability in real-world operational environments.