Detecting Harmful Algae Blooms (HABs) on the Ohio River Using Landsat and Google Earth Engine

Highlights

- Satellite analysis revealed the 2015 Ohio River HAB event affected 636.5 river miles, representing a more than 20-fold increase compared to the 30-mile extent detected through ground-based monitoring alone.

- The ensemble machine learning approach combining Support Vector Regression, Neural Networks, and Extreme Gradient Boosting achieved a correlation coefficient of 0.85 with ground-truth measurements, demonstrating operational reliability for large river systems.

- This study provides a validated operational framework for integrating satellite-based HAB monitoring with existing ground-based surveillance systems in large river environments.

- The quantitative relationships between environmental factors and bloom development provide essential tools for climate change adaptation planning and future HAB risk assessment.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Current Monitoring Approaches and Limitations

1.3. Remote Sensing Applications for Monitoring HABs

2. Materials and Methods

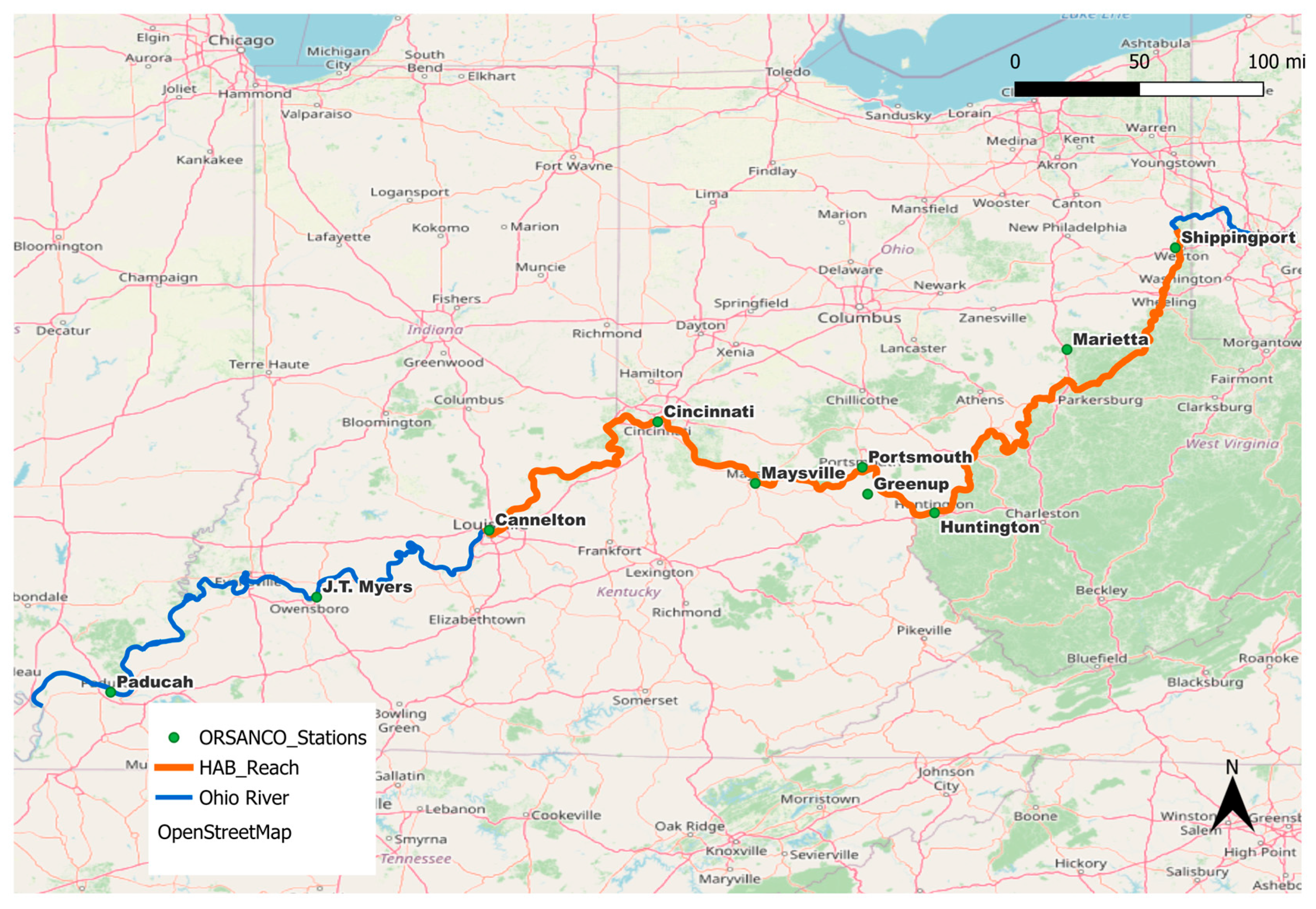

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

- Microcystin concentration (μg/L) via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA);

- Chlorophyll-a levels via fluorometric analysis;

- Water temperature (°C);

- Dissolved oxygen (mg/L);

- Turbidity (NTU);

- Flow velocity (m/s).

2.2. Satellite Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.1. Landsat 7 and 8 Imagery Selection

- Temporal compositing: Combining multiple overpasses within 8-day windows to fill spatial gaps;

- Multi-path coverage: The Ohio River spans four path/row combinations (paths 17–18, rows 32–33), providing overlapping coverage that minimizes gap impacts;

- Selective scene use: SLC gaps were evaluated on a scene-by-scene basis, with scenes retained when gaps did not affect the active river channel;

- Gap interpolation: For narrow SLC gaps (<2 pixels) crossing the river, linear interpolation from adjacent valid pixels was applied.

- Band 1 (Blue): 450–520 nm

- Band 2 (Green): 520–600 nm

- Band 3 (Red): 630–690 nm

- Band 4 (Near-Infrared, NIR): 770–900 nm

- Band 5 (Shortwave Infrared 1, SWIR1): 1550–1750 nm

- Band 7 (Shortwave Infrared 2, SWIR2): 2090–2350 nm

- Band 2 (Blue): 450–510 nm

- Band 3 (Green): 530–590 nm

- Band 4 (Red): 640–670 nm

- Band 5 (Near-Infrared, NIR): 850–880 nm

- Band 6 (Shortwave Infrared 1, SWIR1): 1570–1650 nm

- Band 7 (Shortwave Infrared 2, SWIR2): 2110–2290 nm

- Cloud coverage < 20% over study area

- Solar zenith angle < 60° (to minimize sun glint)

- No sensor anomalies or data quality issues flagged in QA bands

- For Landsat 7: SLC gaps not intersecting primary river corridor

- Temporal coincidence within ±3 days of ground sampling when available

- NIR: L7_harmonized = 0.9723 × L7_original + 0.0005

- Red: L7_harmonized = 0.9237 × L7_original + 0.0034

- SWIR1: L7_harmonized = 0.9548 × L7_original + 0.0022

2.2.2. Atmospheric Correction

- Rayleigh scattering (molecular atmosphere);

- Aerosol scattering and absorption;

- Water vapor absorption;

- Ozone absorption.

2.2.3. Adjacency Effect Considerations

- Buffer exclusion: Water pixels within 90 m (3 Landsat pixels) of land boundaries were excluded from analysis;

- Narrow section masking: River sections < 270 m width had insufficient valid water pixels after buffering and were excluded, creating data gaps representing ~18% of total river length;

- Visual inspection: Remaining pixels were visually inspected for anomalous brightness suggesting residual land contamination.

2.3. Google Earth Engine Implementation

2.3.1. Study Area Definition

2.3.2. Image Collection and Filtering

2.3.3. Mosaicking and Compositing

2.4. Spectral Index Calculation

2.4.1. Floating Algae Index (FAI)

- R_red = Band 4

- R_NIR = Band 5

- R_SWIR1 = Band 6

2.4.2. Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI)

- R_red = Band 4 (640–670 nm)

- R_NIR = Band 5 (850–880 nm)

2.5. Machine Learning Model Development

2.5.1. Model Architecture

- Kernel: Radial basis function (RBF)

- Regularization parameter (C): 100

- Kernel coefficient (γ): 0.001

- Epsilon: 0.1

- Architecture: 8 input features → 50 neurons (hidden layer 1) → 25 neurons (hidden layer 2) → 1 output

- Activation function: Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU)

- Solver: Adam optimizer

- Learning rate: 0.001

- Max iterations: 500

- Number of estimators: 100

- Maximum tree depth: 5

- Learning rate: 0.1

- Subsample ratio: 0.8

2.5.2. Input Features

- Blue reflectance (Band 2)

- Green reflectance (Band 3)

- Red reflectance (Band 4)

- NIR reflectance (Band 5)

- SWIR1 reflectance (Band 6)

- SWIR2 reflectance (Band 7)

- FAI (calculated)

- NDCI (calculated)

2.5.3. Target Variable

2.5.4. Training and Validation Approach

- Training period: 15 August–15 September 2015 (n = 62 matched satellite-ground pairs)

- Testing period: 16 September–30 September 2015 (n = 26 matched satellite-ground pairs)

- Training performance: assessed via 5-fold cross-validation within the training period

- Testing performance: assessed on the completely independent 16–30 September test period

- Overfitting assessment: quantified as the difference between training and testing R2 values, with differences < 0.05 considered acceptable

2.5.5. Ensemble Method

- Weights: w_SVR, w_NN, w_XGB

- Constraint: w_SVR + w_NN + w_XGB = 1, all weights ≥ 0

- SVR: 0.25

- NN: 0.30

- XGB: 0.45

2.6. Spatio-Temporal Matching Protocol

2.6.1. Buffer-Based Matching

- Spatial uncertainty: GPS positioning error (±5–10 m) and Landsat geolocation accuracy (±30 m LE90).

- Downstream transport: With average Ohio River flow velocity of 0.5–0.8 m/s and typical 1–3-day lag between satellite overpass and ground sampling, water parcels travel 4–21 km downstream. A 5 km buffer captures approximately 50% of this transport envelope in both upstream and downstream directions.

Enhanced Dynamic Buffer Approach

- Base_buffer = 5 km (determined through optimization testing balancing spatial accuracy vs. successful matching rate)

- Flow_velocity = measured river velocity at the sampling station (m/s), obtained from ORSANCO flow records

- Time_difference = hours between Landsat overpass time and ground sample collection time

2.6.2. Pixel Extraction and Aggregation

- Median predicted microcystin (primary metric);

- Mean predicted microcystin;

- Standard deviation (spatial variability indicator);

- Number of valid pixels.

2.6.3. Temporal Constraints

2.7. Validation Metrics

- Sensitivity: True positive rate (correctly detected blooms)

- Specificity: True negative rate (correctly identified non-blooms)

2.8. Sensitivity Analyses

- Buffer size variation: Validation repeated using 1 km, 5 km, and 10 km buffer radii

- Individual vs. ensemble models: Comparison of SVR, NN, XGB, and ensemble performance

- Single-index baselines: Performance of NDCI-only and FAI-only linear regression models

3. Results

3.1. Enhanced Spatial Detection Capabilities

3.1.1. Spatial Coverage Comparison and Detection Patterns

3.1.2. Validation and Uncertainty

3.1.3. Implications for Water Resource Management

3.2. Early Warning System Development

3.2.1. Temporal Detection Sequence and Validation

3.2.2. Quantifying Temporal Advantage

3.2.3. Mechanistic Basis for Early Detection

3.2.4. Operational Implications for Water Management

3.2.5. Validation Against Historical Events

3.3. Machine Learning Integration and Analytical Performance

3.3.1. Individual Algorithm Performance

3.3.2. Ensemble Integration and Combined Performance

3.3.3. Feature Importance and Model Interpretability

3.3.4. Cross-Validation Robustness and Environmental Variability

3.4. Field Validation Results

3.4.1. Dynamic Buffer Validation Methodology

3.4.2. Spatial Validation Performance

3.4.3. Temporal Validation and Early Detection Capability

3.4.4. Environmental Relationships and Bloom Dynamics

3.4.5. Validation Accuracy Assessment and Uncertainty Analysis

- Pearson correlation coefficient: r = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82–0.91);

- Root Mean Square Error: RMSE = 0.023 (normalized RMSE = 18%);

- Mean Absolute Error: MAE = 0.018;

- Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency: NSE = 0.82;

- Bias: −0.003 (indicating slight underestimation tendency).

3.5. Technical Implementation and Operational Feasibility

3.5.1. Multi-Index Spectral Analysis Performance

3.5.2. Atmospheric Correction and Quality Control

3.5.3. Computational Efficiency and Scalability

3.5.4. Operational Deployment Framework

3.5.5. Integration with Existing Monitoring Systems

3.5.6. Cost-Effectiveness and Resource Optimization

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Limitations and Future Directions

4.1.1. Temporal and Spatial Resolution Constraints

4.1.2. Model Generalizability and Training Data

4.1.3. Atmospheric Correction and Radiometric Uncertainty

4.1.4. Detection Limitations and System-Specific Considerations

4.1.5. Future Enhancement Opportunities

- Multi-platform integration incorporating Sentinel-2 MSI (10-m resolution, 5-day revisit) could improve temporal resolution to 2–3 days, substantially reducing cloud cover impacts and enabling detection of shorter-duration events. Machine learning approaches have proven adaptable across diverse remote sensing application [48], supporting transferability to multi-platform integration.

- Enhanced atmospheric correction algorithms specifically optimized for inland waters (e.g., ACOLITE, SeaDAS, iCOR) could reduce residual uncertainties, particularly when integrated with AERONET aerosol monitoring.

- Species discrimination capabilities through additional spectral features, particularly phycocyanin-sensitive bands available on Sentinel-3 OLCI (620 nm), could improve distinction between cyanobacterial blooms and other phytoplankton assemblages. Integration of AI approaches with remote sensing has shown promise in monitoring wetland ecosystems [49], suggesting potential for adaptation to HAB species discrimination.

- Predictive modeling integration coupling satellite observations with hydrodynamic-ecological models could extend early warning beyond the current 5–7-day advantage by forecasting bloom development based on environmental drivers.

- Multi-year validation programs encompassing diverse bloom events, species compositions, and environmental conditions would strengthen confidence in model generalizability and operational reliability.

- Cross-system validation extending methodology to other major river systems (Mississippi, Columbia, Tennessee, Missouri) would test generalizability while building robust multi-system training datasets.

4.2. Implications for Water Resource Management

4.2.1. Public Health Protection and Operational Integration

4.2.2. Economic Efficiency and Strategic Watershed Management

4.2.3. Climate Change Adaptation and Long-Term Planning

4.3. Scientific Contributions and Broader Context

4.3.1. Advances in Riverine HAB Understanding

4.3.2. Methodological Advances and Framework Contributions

4.3.3. Integration Across Scales and Future Research Directions

- Multi-system validation testing methodology generalizability across diverse river systems with different hydrodynamic characteristics, optical properties, and bloom species composition.

- Species-specific detection and toxin prediction through integration of phycocyanin-sensitive spectral features and machine learning approaches utilizing full spectral signatures [49].

- Predictive modeling integration coupling satellite observations with hydrodynamic-ecological models to extend early warning capabilities beyond current 5–7-day detection advantage.

- Enhanced atmospheric correction and radiometric validation through dedicated campaigns with coincident optical measurements.

- High-frequency temporal monitoring integrating multiple satellite platforms (Landsat 8/9, Sentinel-2A/B, Sentinel-3A/B) to achieve 2–3-day temporal resolution [48].

- Long-term trend analysis applying methodology to historical Landsat archives (1984−present) to reveal temporal changes in HAB frequency, intensity, and spatial distribution.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDOM | Carbon Dissolved Organic Matter |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ECCC | Environment and Climate Change Canada |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| FAI | Floating Algae Index |

| HAB | Harmful Algae Bloom |

| HIS | Hyperspectral Imaging |

| L&D | Locks and Dam |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography with tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MERIS | Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| MSS | Multispectral Scanner |

| NDCI | Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| OLCI | Ocean and Land Colour instrument |

| ORM | Ohio River Mile |

| ORSANCO | Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission |

| RM | River Mile |

| Rrs | Remote Sensing Reflectance |

| SPATT | Solid Phase Absorption Toxin Tracking |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TDI | Toxin Diversity Index |

| UAS | Unmanned Aircraft System |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| ```javascript var collection = ee.ImageCollection(‘LANDSAT/LC08/C02/T1_L2’) .filterBounds(studyArea) .filterDate(‘2015-08-15’, ‘2015-09-30’) .filter(ee.Filter.lt(‘CLOUD_COVER’, 70)) .map(applyScaleFactors) .map(maskClouds); ``` |

Appendix A.2

| ```javascript function enhancedWaterMask(image) { var ndwi = image.normalizedDifference([‘GREEN’, ‘NIR’]); var turbidityMask = image.normalizedDifference([‘RED’, ‘GREEN’]); var combinedMask = ndwi.gt(0.1).and(turbidityMask.lt(0.2)); return image.updateMask(combinedMask); } ``` |

References

- Kislik, C.; Dronova, I.; Grantham, T.E.; Kelly, M. Mapping algal bloom dynamics in small reservoirs using Sentinel-2 imagery in Google Earth Engine. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 140, 109041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, F.d.L.; Nagel, G.W.; Maciel, D.A.; Carvalho, L.A.S.d.; Martins, V.S.; Barbosa, C.C.F.; Novo, E.M.L.d.M. AlgaeMAp: Algae Bloom Monitoring Application for Inland Waters in Latin America. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietch, C.T.; Gains-Germain, L.; Lazorchak, J.; Keely, S.P.; Youngstrom, G.; Urichich, E.M.; Astifan, B.; DaSilva, A.; Mayfield, H. Development of a Risk Characterization Tool for Harmful Cyanobacteria Blooms on the Ohio River. Water 2022, 14, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio, R.J.; Linhoss, A.; Murdock, J.; Yeager-Armstead, M.; Raju, M. Sensitivity analysis of a hydrodynamic and harmful algal model in a riverine system. Ecol. Model. 2024, 497, 110846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO). Ohio River Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring and Response Plan. 2021. Available online: https://www.orsanco.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/FINAL-2021-HAB-Monitoring-and-Response-Plan.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Howard, M.D.A.; Smith, J.; Caron, D.A.; Kudela, R.M.; Loftin, K.; Hayashi, K.; Fadness, R.; Fricke, S.; Kann, J.; Roethler, M.; et al. Integrative monitoring strategy for marine and freshwater harmful algal blooms and toxins across the freshwater-to-marine continuum. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO). Harmful Algal Blooms. Available online: https://www.orsanco.org/programs/harmful-algal-blooms/ (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Preece, E.P.; Cooke, J.; Plaas, H.; Sabo, A.; Nelson, L.; Paerl, H.W. Managing a Cyanobacteria Harmful Algae Bloom ‘Hotspot’ in the Sacramento—San Joaquin Delta, California. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwaran, A.; Kayode, A.J.; Moloantoa, K.M.; Khetsha, Z.P.; Unuofin, J.O. Cyanobacteria Harmful Algae Blooms: Causes, Impacts, and Risk Management. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.K.; Bouska, W.W.; Eitzmann, J.L.; Pilger, T.J.; Pitts, K.L.; Riley, A.J.; Schloesser, J.T.; Thornbrugh, D.J. Eutrophication of US freshwaters: Analysis of potential economic damages. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Klaiber, H.A. Bloom and bust? Water quality valuation in an algae-impacted watershed. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2017, 46, 306–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, M.; Sinha, S.K.; Lupi, F. Economic Benefits of Reducing Harmful Algal Blooms in Lake Erie; International Joint Commission, Great Lakes Regional Office: Windsor, ON, Canada, 2015.

- Stumpf, R.P.; Wynne, T.T.; Baker, D.B.; Fahnenstiel, G.L. Interannual variability of cyanobacterial blooms in Lake Erie. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.A.D.; Alonso, C.A.; García, A.A. Remote Sensing as a Tool for Monitoring Water Quality Parameters for Mediterranean Lakes of European Union Water Framework Directive (WFD) and as a System of Surveillance of Cyanobacterial Harmful Algae Blooms (SCyanoHABs). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 181, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorham, T.; Jia, Y.; Shum, C.K.; Lee, J. Ten-year survey of cyanobacterial blooms in Ohio’s waterbodies using satellite remote sensing. Harmful Algae 2017, 66, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres Palenzuela, J.M.; Vilas, L.G.; Bellas Aláez, F.M.; Pazos, Y. Potential Application of the New Sentinel Satellites for Monitoring of Harmful Algal Blooms in the Galician Aquaculture. Thalass. Rev. Cienc. Mar. 2020, 36, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Mutanga, O. Google Earth Engine applications since inception: Usage, trends, and potential. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S.; et al. Google Earth Engine cloud computing platform for remote sensing big data applications: A comprehensive review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiminia, H.; Salehi, B.; Mahdianpari, M.; Quackenbush, L.; Adeli, S.; Brisco, B. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 164, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janga, B.; Asamani, G.; Sun, Z.; Cristea, N. A Review of Practical AI for Remote Sensing in Earth Sciences. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Kumar, L. Google Earth Engine applications. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P. Progress and trends in the application of Google Earth Engine to remote sensing at scale. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Matsushita, B.; Matsuzaki, H.; Kamiya, K.; Kobinata, H. Monitoring levels of cyanobacterial blooms using the visual cyanobacteria index (VCI) and floating algae index (FAI). ITC J. 2015, 38, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visitacion, M.R.; Alnin, C.A.; Ferrer, M.R.; Suñiga, L. Detection of Algal Bloom in the Coastal Waters of Boracay, Philippines Using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Floating Algae Index (FAI). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-4/W19, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adegun, A.A.; Viriri, S.; Tapamo, J.-R. Review of deep learning methods for remote sensing satellite images classification: Experimental survey and comparative analysis. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, A.; Kumar, S. Deep Learning Methods for Land Cover and Land Use Classification in Remote Sensing: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), Noida, India, 4–5 June 2020; pp. 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Jain, S.; Dube, N.; Varghese, N. Earth Observation Data Analytics Using Machine and Deep Learning: Modern Tools, Applications and Challenges, 1st ed.; Institution of Engineering & Technology: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Shi, J.; Gu, L. A review of deep learning methods for semantic segmentation of remote sensing imagery. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 169, 114417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.R.; Kumar, A.; Temimi, M.; Bull, D.R. HABNet: Machine Learning, Remote Sensing Based Detection and Prediction of Harmful Algal Blooms. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1912.02305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, K.S.; Sahu, S.R.; Singh, S.K.; Chander, S.; Gujrati, A. Water Quality Analysis Using Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI) and Normalized Difference Turbidity Index (NDTI), Using Google Earth Engine Platform. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Modeling, Simulation & Intelligent Computing (MoSICom), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 7–9 December 2023; pp. 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Zhang, X.; Dong, R. Long-Term Spatial and Temporal Monitoring of Cyanobacteria Blooms Using MODIS on Google Earth Engine: A Case Study in Taihu Lake. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, M.; Wei, J.; He, Y.; Niu, L.; Li, H.; Xu, G. Adaptive Threshold Model in Google Earth Engine: A Case Study of Ulva prolifera Extraction in the South Yellow Sea, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Kovalskyy, V.; Zhang, H.K.; Vermote, E.F.; Yan, L.; Kumar, S.S.; Egorov, A. Characterization of Landsat-7 to Landsat-8 reflective wavelength and normalized difference vegetation index continuity. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, T.; Martínez-López, J.; Llodrà-Llabrés, J.; Alcaraz-Segura, D.; Pérez-Martínez, C. Dataset of processed Sentinel-2 images for chlorophyll-a estimation in high-altitude lakes in the Sierra Nevada, Spain [Dataset]. Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q.; Ruddick, K. Atmospheric correction of metre-scale optical satellite data for inland and coastal water applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825−2830. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroming, S.; Robertson, M.; Mabee, B.; Kuwayama, Y.; Schaeffer, B. Quantifying the Human Health Benefits of Using Satellite Information to Detect Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms and Manage Recreational Advisories in U.S. Lakes. Geohealth 2020, 4, e2020GH000254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höhl, A.; Obadic, I.; Fernández Torres, M.Á.; Najjar, H.; Oliveira, D.; Akata, Z.; Dengel, A.; Zhu, X.X. Opening the Black-Box: A Systematic Review on Explainable AI in Remote Sensing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, J.; Burgert, T.; Demir, B. On the Effectiveness of Methods and Metrics for Explainable AI in Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.05916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, O.S.; Acar, U.; Sanli, F.B.; Gülgen, F.; Ateş, A.M. Investigation of Water Quality in Izmir Bay with Remote Sensing Techniques Using NDCI on Google Earth Engine Platform. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, 13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekki, J. Airborne Hyperspectral Sensing of Harmful Algal Blooms in the Great Lakes Region: System Calibration and Validation from Photons to Algae Information: The Processes In-Between; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, F.; Buis, K.; Verschoren, V.; Meire, P. Depth Estimation of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in Clear Water Streams Using Low-Altitude Optical Remote Sensing. Sensors 2015, 15, 25287–25312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, B.; Dwivedi, R. Review on remote sensing methods for landslide detection using machine and deep learning. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.K.; Jain, V.; Yadav, U. Monitoring India’s Ramsar Wetlands: Water Quality and Ecosystem Health via Remote Sensing and AI, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaiser, D.; Qu, J.J. Detecting Harmful Algae Blooms (HABs) on the Ohio River Using Landsat and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244010

Kaiser D, Qu JJ. Detecting Harmful Algae Blooms (HABs) on the Ohio River Using Landsat and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244010

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaiser, Douglas, and John J. Qu. 2025. "Detecting Harmful Algae Blooms (HABs) on the Ohio River Using Landsat and Google Earth Engine" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244010

APA StyleKaiser, D., & Qu, J. J. (2025). Detecting Harmful Algae Blooms (HABs) on the Ohio River Using Landsat and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4010. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244010