Advancements in Satellite Observations of Inland and Coastal Waters: Building Towards a Global Validation Network

Highlights

- Review of the state of science of satellite-derived optical and water quality products.

- Field data measurement review for remote sensing validation in inland and coastal waters.

- Guidance for the scientific community to consider when implementing field campaigns to collect data for remote sensing validation needs.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Why Are Inland and Coastal Waters Important?

1.2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Remote Sensing as a Tool

1.3. Gaining User Trust and the Role of Validation

1.4. Publication Aims and Objectives

2. State of the Science

2.1. Advancements Since 2015

2.2. Current & Upcoming Missions

2.3. Existing In Situ Sensor Technology

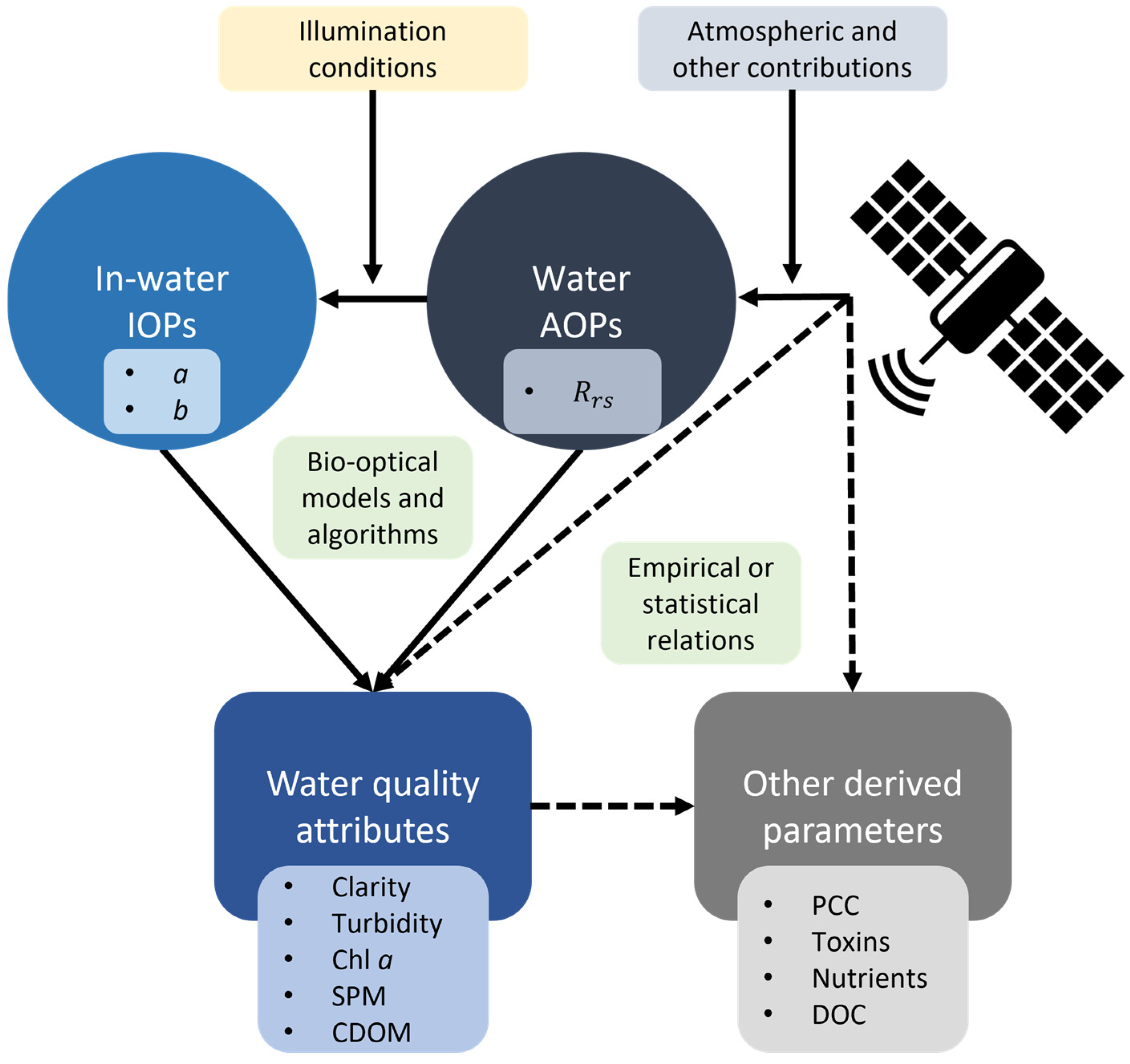

2.3.1. IOPs, AOPs, and Water Quality Attributes

2.3.2. IOP Measurements

2.3.3. AOP Measurements

2.3.4. Water Quality Measurements

2.4. Existing Databases

2.5. The Validation Process

3. Outstanding Validation Gaps

3.1. Validation Gaps for Rrs and Water Quality Parameters

3.1.1. Remote Sensing Reflectance (Rrs)

3.1.2. Water Quality Parameters

3.2. From Open Ocean to Inland and Coastal Water Validation Protocols

3.2.1. Time Window

3.2.2. Averaging and Multi-Pixel Analysis

3.2.3. Atmospheric Correction

3.2.4. Light Assumptions

3.2.5. Case 1 vs. Case 2 Assumptions

3.3. In Situ Sensor Technologies for Measurement of IOPs

3.3.1. Absorption

3.3.2. Backscattering

3.4. Current Validation Gaps

3.4.1. General Trends

3.4.2. Gaps in Parameters

3.4.3. Geographic Gaps

3.4.4. User Engagement Gaps

4. Research Opportunities

4.1. Key Research Opportunities and Considerations

- Increased validation studies in understudied regions.

- Development of validation educational resources that are both multilingual and written for remote sensing experts and non-experts.

- Continued development of protocols for validation in inland and coastal waters.

- Communication of uncertainties and expectations related to field measurements and satellite data products.

- Further research on specific validation issues for inland and coastal waters.

4.1.1. Validation in Understudied Regions

- Literature supports that 48.9% of validation studies are performed in the United States and China. As such, there is limited global representation of validation studies, which is probably linked to the lack of adequate training, lack of equipment, or different scientific priorities. Some regions are particularly underrepresented, including Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa.

4.1.2. Educational Resources

- Increase multilingual education of end-users so they can learn how satellite-derived products were created and their potential applications and limitations. Educational materials could include a variety of formats to account for differences in end-user capabilities (remote sensing experts and non-experts).

- Improve multilingual hands-on training for water quality professionals and volunteers to expand data collection and support training on the use of satellite-derived data for water quality management.

4.1.3. Protocol Development

- Translate protocols and standard operating procedures to languages other than English to promote the dissemination of the content.

- Consider specific characteristics (e.g., optically shallow waters) when developing and/or adapting available (open ocean) protocols for measurements in inland and coastal waters.

- Collect matched data pairs of in situ reflectance and water quality attributes to help improve algorithm and model development, including the revision of implicit assumptions of open ocean models that are often adapted to inland or coastal waters.

- Record and report validation measurement metadata in a standardized format, including at least the following information: latitude, longitude, date/time, Secchi depth, water depth, elevation, wind conditions, cloud cover, and water temperature. It is also desirable to record the methods used for data collection and processing, including sensor manufacturer and model when applicable.

- Consider the appropriate sampling time-windows before and after satellite data acquisition for inland and coastal waters. The development of a time-window guide considering different characteristics of the water bodies would be very useful when designing validation sampling plans. Parameters that may be important to consider when developing a time-window guide include: tidal range (coastal waters) or mean residence time (inland waters); diurnal variability; spatial variability (homogeneous or heterogeneous); spatial resolution of the satellite sensor; and sampling accessibility (e.g., Tables S4 and S5 of the Supplementary Materials).

- Develop standard operating procedures to account for uncertainty and environmental variability of measurements. This could include but is not limited to: replication of measurements or samples over a short period of time (in the scale of minutes) to reduce and account for random errors; and report, at least, simple uncertainty quantifications, such as standard deviation, percentiles, and number of samples.

4.1.4. Data Uncertainty and Expectations

- Clearly communicate uncertainties associated with both field measurements and satellite data products.

- Identify the conditions or regions for which a satellite data product is expected to perform well or poorly.

- Focus on understanding and defining which uncertainties are “acceptable” across dynamic systems through improving the understanding of end-user needs.

4.1.5. Knowledge Gaps

- Severity of the impacts of known issues (e.g., adjacency effects, shading and reflectance from the deployment platform) on water quality attribute retrievals and radiometric measurements for inland and coastal waters.

- Atmospheric correction for coastal and inland waters, including: the validation of available atmospheric correction procedures across varying atmospheric and water column states to ensure robustness, the development of atmospheric corrections for inland and coastal waters that implicitly account for straylight from land adjacent pixels, and to this end, generating validation data sets impacted by adjacency effects so that tools can be generated to further address the issue.

- Effects of particle size (algal and non-algal), composition of dissolved and particulate matter, and algal community composition and pigments on the absorption and scattering properties of inland and coastal water bodies (i.e., on the IOPs) to better understand their effects on aquatic reflectance.

- Improving in situ absorption and scattering sensor designs or developing corrections for existing sensors that work well in highly attenuating/scattering mediums, which are often common in inland/coastal waters and incorporate these measurements in field campaigns.

- Characterization of known interferences and issues (e.g., NPQ, temperature quenching, etc.) with in situ fluorometry-based sensors (e.g., Chl a, CDOM, accessory algal pigments) to expand their use as satellite validation data.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grizzetti, B.; Poikane, S. The Importance of Inland Waters. In Wetzel’s Limnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 7–13. ISBN 978-0-12-822701-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hoepffner, N.; Zibordi, G. Remote Sensing of Coastal Waters. In Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 732–741. ISBN 978-0-12-374473-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Gosselink, J.G. Wetlands, 5th ed.; Environmental/water supply; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-67682-0. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN) Water (Ed.) Valuing Water, The United Nations World Water Development Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-3-100434-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Stocker, B.D.; Zhang, Z.; Malhotra, A.; Melton, J.R.; Poulter, B.; Kaplan, J.O.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Siebert, S.; Minayeva, T.; et al. Extensive Global Wetland Loss over the Past Three Centuries. Nature 2023, 614, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-Resolution Mapping of Global Surface Water and Its Long-Term Changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Bernhardt, E.S. Inland Waters. In Biogeochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 293–360. ISBN 978-0-12-814608-8. [Google Scholar]

- Heino, J.; Alahuhta, J.; Bini, L.M.; Cai, Y.; Heiskanen, A.; Hellsten, S.; Kortelainen, P.; Kotamäki, N.; Tolonen, K.T.; Vihervaara, P.; et al. Lakes in the Era of Global Change: Moving beyond Single-lake Thinking in Maintaining Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Biol. Rev. 2021, 96, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno, J.; Harrison, I.J.; Dudgeon, D.; Clausnitzer, V.; Darwall, W.; Farrell, T.; Savy, C.; Tockner, K.; Tubbs, N. Sustaining Freshwater Biodiversity in the Anthropocene. In The Global Water System in the Anthropocene; Bhaduri, A., Bogardi, J., Leentvaar, J., Marx, S., Eds.; Springer Water; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 247–270. ISBN 978-3-319-07547-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dethier, E.N.; Renshaw, C.E.; Magilligan, F.J. Rapid Changes to Global River Suspended Sediment Flux by Humans. Science 2022, 376, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maúre, E.D.R.; Terauchi, G.; Ishizaka, J.; Clinton, N.; DeWitt, M. Globally Consistent Assessment of Coastal Eutrophication. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Nicolai, M., Oken, A., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-009-15796-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Invasive Alien Species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botrel, M.; Maranger, R. Global Historical Trends and Drivers of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation Quantities in Lakes. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2493–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jeppesen, E.; Liu, X.; Qin, B.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Thomaz, S.M.; Deng, J. Global Loss of Aquatic Vegetation in Lakes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 173, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunic, J.C.; Brown, C.J.; Connolly, R.M.; Turschwell, M.P.; Côté, I.M. Long-term Declines and Recovery of Meadow Area across the World’s Seagrass Bioregions. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4096–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wildlife Federation (WWF). Building a Nature-Positive Society; CBS Library: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2022; ISBN 978-2-88085-316-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hallegraeff, G.M.; Anderson, D.M.; Belin, C.; Bottein, M.-Y.D.; Bresnan, E.; Chinain, M.; Enevoldsen, H.; Iwataki, M.; Karlson, B.; McKenzie, C.H.; et al. Perceived Global Increase in Algal Blooms Is Attributable to Intensified Monitoring and Emerging Bloom Impacts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.; Kudela, R.M.; Velo-Suárez, L. Developing Global Capabilities for the Observation and Prediction of Harmful Algal Blooms. In Oceans and Society: Blue Planet; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4438-6116-8. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, M.W. A Current Review of Empirical Procedures of Remote Sensing in Inland and Near-Coastal Transitional Waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 6855–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, M.; Melesse, A.; Reddi, L. A Comprehensive Review on Water Quality Parameters Estimation Using Remote Sensing Techniques. Sensors 2016, 16, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnhöfer, K.; Oppelt, N. Remote Sensing for Lake Research and Monitoring—Recent Advances. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, E.; Dekker, A. Application of Remote Sensing Techniques for Water Quality Monitoring. Hydrobiol. Bull. 1986, 20, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, S.N.; Pavelsky, T.M.; Jensen, D.; Simard, M.; Ross, M.R.V. Research Trends in the Use of Remote Sensing for Inland Water Quality Science: Moving Towards Multidisciplinary Applications. Water 2020, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, C.B.; Greb, S.; Aurin, D.; DiGiacomo, P.M.; Lee, Z.; Twardowski, M.; Binding, C.; Hu, C.; Ma, R.; Moore, T.; et al. Aquatic Color Radiometry Remote Sensing of Coastal and Inland Waters: Challenges and Recommendations for Future Satellite Missions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 160, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, L.; Urquhart, E.; Georgantzis, N.; Schaeffer, B.; Simmons, R.; Hoque, B.; Neely, M.B.; Neil, C.; Oliver, J.; Tyler, A. Perspectives on User Engagement of Satellite Earth Observation for Water Quality Management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, B.; Celliers, L.; Assad, L.P.D.F.; Heymans, J.J.; Rome, N.; Thomas, J.; Anderson, C.; Behrens, J.; Calverley, M.; Desai, K.; et al. The Role of Stakeholders in Creating Societal Value from Coastal and Ocean Observations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podestá, G.P.; Natenzon, C.E.; Hidalgo, C.; Ruiz Toranzo, F. Interdisciplinary Production of Knowledge with Participation of Stakeholders: A Case Study of a Collaborative Project on Climate Variability, Human Decisions and Agricultural Ecosystems in the Argentine Pampas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 26, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, C.B.; Greb, S. Inland and Coastal Waters. EoS Trans. 2012, 93, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.S.; Dowell, M.D.; Bradt, S.; Ruiz Verdu, A. An Optical Water Type Framework for Selecting and Blending Retrievals from Bio-Optical Algorithms in Lakes and Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 143, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, V.; Peterson, K.T.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Sidike, P.; Sloan, J.; Greeling, B.A.; Maalouf, S.; Adams, C. Monitoring Inland Water Quality Using Remote Sensing: Potential and Limitations of Spectral Indices, Bio-Optical Simulations, Machine Learning, and Cloud Computing. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 205, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahat, S.H.; Steissberg, T.; Chang, W.; Chen, X.; Mandavya, G.; Tracy, J.; Wasti, A.; Atreya, G.; Saki, S.; Bhuiyan, M.A.E.; et al. Remote Sensing-Enabled Machine Learning for River Water Quality Modeling under Multidimensional Uncertainty. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighkia, M.; Datta, B.; Saeedipour, P.; Abdoli, A. Predicting Water Quality Distribution of Lakes through Linking Remote Sensing–Based Monitoring and Machine Learning Simulation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranathan, A.M.; Werther, M.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Odermatt, D.; Pahlevan, N. Assessment of Advanced Neural Networks for the Dual Estimation of Water Quality Indicators and Their Uncertainties. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1383147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Pahlevan, N.; Schalles, J.; Ruberg, S.; Errera, R.; Ma, R.; Giardino, C.; Bresciani, M.; Barbosa, C.; Moore, T.; et al. A Chlorophyll-a Algorithm for Landsat-8 Based on Mixture Density Networks. Front. Remote Sens. 2021, 1, 623678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouris, D.M.; Hestir, E.L.; Fleck, J.; Hansen, J.A.; Bergamaschi, B.A. An Integrated Sensor Network and Data Driven Approach to Satellite Remote Sensing of Dissolved Organic Matter. Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2024EA004048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Karger, F.E.; Hestir, E.; Ade, C.; Turpie, K.; Roberts, D.A.; Siegel, D.; Miller, R.J.; Humm, D.; Izenberg, N.; Keller, M.; et al. Satellite Sensor Requirements for Monitoring Essential Biodiversity Variables of Coastal Ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, C.D. Estimation of the Remote-Sensing Reflectance from above-Surface Measurements. Appl. Opt. 1999, 38, 7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werdell, P.J.; McKinna, L.I.W.; Boss, E.; Ackleson, S.G.; Craig, S.E.; Gregg, W.W.; Lee, Z.; Maritorena, S.; Roesler, C.S.; Rousseaux, C.S.; et al. An Overview of Approaches and Challenges for Retrieving Marine Inherent Optical Properties from Ocean Color Remote Sensing. Prog. Oceanogr. 2018, 160, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffione, R.A.; Dana, D.R. Instruments and Methods for Measuring the Backward-Scattering Coefficient of Ocean Waters. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, A. Optical Properties of Pure Water and Pure Seawater. In Optical Aspects of Oceanography; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pegau, W.S.; Gray, D.; Zaneveld, J.R.V. Absorption and Attenuation of Visible and Near-Infrared Light in Water: Dependence on Temperature and Salinity. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegau, W.S.; Zaneveld, J.R.V. Temperature Dependence of the Absorption Coefficient of Pure Water in the Visible Portion of the Spectrum. In Proceedings of the Ocean Optics XII, Bergen, Norway, 13–15 June 1994; pp. 597–604, Volume 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeley, A.R.; Mannino, A. Ocean Optics and Biogeochemistry Protocols for Satellite Ocean Colour Sensor Validation, Volume 1.0: Inherent Optical Property Measurements and Protocols: Absorption Coefficient; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG): Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, K.G.; Voss, K.; Boss, E.; Castagna, A.; Frouin, R.; Gilerson, A.; Hieronymi, M.; Johnson, B.C.; Kuusk, J.; Lee, Z.; et al. A Review of Protocols for Fiducial Reference Measurements of Water Leaving Radiance for Validation of Satellite Remote-Sensing Data over Water. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibordi, G.; Voss, K.J.; Johnson, B.C.; Mueller, J.L. Ocean Optics and Biogeochemistry Protocols for Satellite Ocean Colour Sensor Validation, Volume 3.0: Protocols for Satellite Ocean Colour Data Validation: In Situ Optical Radiometry; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG): Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.; Wei, J.; Shang, Z.; Garcia, R.; Dierssen, H.; Ishizaka, J.; Castagna, A. On-Water Radiometry Measurements: Skylight-Blocked Approach and Data Processing (Appendix to IOCCG Protocol Series (2019). Protocols for Satellite Ocean Colour Data Validation: In Situ Optical Radiometry. Zibordi, G., Voss, K.J., Johnson, B.C. and Mueller, J.L. IOCCG Ocean Optics and Biogeochemistry Protocols for Satellite Ocean Colour Sensor Validation, Volume 3.0, IOCCG, Dartmouth, NS, Canada); IOCCG: Sidney, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z. KPAR: An Optical Property Associated with Ambiguous Values. J. Lake Sci. 2009, 21, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, A.G.; MacLeod, A. End User Consultation Report; SmartSat CRC Ltd.: Adelaide, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Droujko, J.; Molnar, P. Open-Source, Low-Cost, in-Situ Turbidity Sensor for River Network Monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidam, E.F.; Langhorst, T.; Goldstein, E.B.; McLean, M. OpenOBS: Open-source, Low-cost Optical Backscatter Sensors for Water Quality and Sediment-transport Research. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2022, 20, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watras, C.J.; Morrison, K.A.; Rubsam, J.L.; Hanson, P.C.; Watras, A.J.; LaLiberte, G.D.; Milewski, P. A Temperature Compensation Method for Chlorophyll and Phycocyanin Fluorescence Sensors in Freshwater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2017, 15, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, A.; Novak, M.G.; Nelson, N.B.; Belz, M.; Berthon, J.-F.; Blough, N.V.; Boss, E.; Bricaud, A.; Chaves, J.; Del Castillo, C.; et al. Measurement Protocol of Absorption by Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) and Other Dissolved Materials. In Inherent Optical Property Measurements and Protocols: Absorption Coefficient; IOCCG Ocean Optics and Biogeochemistry Protocols for Satellite Ocean Colour Sensor Validation; IOCCG: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Watras, C.J.; Hanson, P.C.; Stacy, T.L.; Morrison, K.M.; Mather, J.; Hu, Y.-H.; Milewski, P. A Temperature Compensation Method for CDOM Fluorescence Sensors in Freshwater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2011, 9, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.W.; Werdell, P.J. A Multi-Sensor Approach for the on-Orbit Validation of Ocean Color Satellite Data Products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 102, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multiscale Observation Networks for Optical monitoring of Coastal Waters, Lakes and Estuaries (MONOCLE) Project Resources. Available online: https://monocle-h2020.eu/Project_Resources.html (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Group on Earth Observations (GEO) AquaWatch, 2024. Water Quality Database Inventory. Available online: https://www.geoaquawatch.org/water-quality-database-inventory/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Burggraaff, O. Biases from Incorrect Reflectance Convolution. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahlevan, N.; Smith, B.; Schalles, J.; Binding, C.; Cao, Z.; Ma, R.; Alikas, K.; Kangro, K.; Gurlin, D.; Hà, N.; et al. Seamless Retrievals of Chlorophyll-a from Sentinel-2 (MSI) and Sentinel-3 (OLCI) in Inland and Coastal Waters: A Machine-Learning Approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 240, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, S.K.; Brito, T.V.; Welling, D.T. Measures of Model Performance Based on the Log Accuracy Ratio. Space Weather 2018, 16, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, A.; Ruddick, K.G.; Nechad, B.; Doxaran, D.; Knaeps, E. A Single Algorithm to Retrieve Turbidity from Remotely-Sensed Data in All Coastal and Estuarine Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 156, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Smith, B.; Alikas, K.; Anstee, J.; Barbosa, C.; Binding, C.; Bresciani, M.; Cremella, B.; Giardino, C.; Gurlin, D.; et al. Simultaneous Retrieval of Selected Optical Water Quality Indicators from Landsat-8, Sentinel-2, and Sentinel-3. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Pang, S.; Cheng, Q. Applicability Evaluation of Landsat-8 for Estimating Low Concentration Colored Dissolved Organic Matter in Inland Water. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichot, C.G.; Tzortziou, M.; Mannino, A. Remote Sensing of Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) Stocks, Fluxes and Transformations along the Land-Ocean Aquatic Continuum: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 242, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Hestir, E.L.; Tufillaro, N.; Palmieri, B.; Acuña, S.; Osti, A.; Bergamaschi, B.A.; Sommer, T. Monitoring Turbidity in San Francisco Estuary and Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Using Satellite Remote Sensing. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2021, 57, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Z.; Carder, K.L.; Arnone, R.A. Deriving Inherent Optical Properties from Water Color: A Multiband Quasi-Analytical Algorithm for Optically Deep Waters. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 5755–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Barreto, B.N.; Hestir, E.L.; Lee, C.M.; Beutel, M.W. Satellite Remote Sensing: A Tool to Support Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring and Recreational Health Advisories in a California Reservoir. GeoHealth 2024, 8, e2023GH000941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R. Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index: A Novel Model for Remote Estimation of Chlorophyll-a Concentration in Turbid Productive Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, C.B.; Chen, H.; McKinley, G.A.; Effler, S.; O’Donnell, D.; Perkins, M.G.; Strait, C. Evaluation and Optimization of Bio-optical Inversion Algorithms for Remote Sensing of Lake Superior’s Optical Properties. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2013, 118, 1696–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, C.B.; Ciochetto, A.B.; Grunert, B.; Yu, A. Expanding Understanding of Optical Variability in Lake Superior with a Four-Year Dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechad, B.; Ruddick, K.G.; Park, Y. Calibration and Validation of a Generic Multisensor Algorithm for Mapping of Total Suspended Matter in Turbid Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, T.T.; Stumpf, R.P.; Tomlinson, M.C.; Dyble, J. Characterizing a Cyanobacterial Bloom in Western Lake Erie Using Satellite Imagery and Meteorological Data. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010, 55, 2025–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Pratolongo, P.; Loisel, H.; Tran, M.D.; Jorge, D.S.F.; Delgado, A.L. Optical Water Characterization and Atmospheric Correction Assessment of Estuarine and Coastal Waters around the AERONET-OC Bahia Blanca. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1305787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, A.I.; Piegari, E.; Rubinstein, L.; Perna, P.; Ruddick, K.G. Using the Automated HYPERNETS Hyperspectral System for Multi-Mission Satellite Ocean Colour Validation in the Río de La Plata, Accounting for Different Spatial Resolutions. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1354662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, K.G.; Brando, V.E.; Corizzi, A.; Dogliotti, A.I.; Doxaran, D.; Goyens, C.; Kuusk, J.; Vanhellemont, Q.; Vansteenwegen, D.; Bialek, A.; et al. WATERHYPERNET: A Prototype Network of Automated in Situ Measurements of Hyperspectral Water Reflectance for Satellite Validation and Water Quality Monitoring. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1347520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, F.P.; Pedocchi, F. Evaluation of ACOLITE Atmospheric Correction Methods for Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 in the Río de La Plata Turbid Coastal Waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sòria-Perpinyà, X.; Delegido, J.; Urrego, E.P.; Ruíz-Verdú, A.; Soria, J.M.; Vicente, E.; Moreno, J. Assessment of Sentinel-2-MSI Atmospheric Correction Processors and In Situ Spectrometry Waters Quality Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q. Adaptation of the Dark Spectrum Fitting Atmospheric Correction for Aquatic Applications of the Landsat and Sentinel-2 Archives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 225, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, R.; Xue, K.; Loiselle, S. The Assessment of Landsat-8 OLI Atmospheric Correction Algorithms for Inland Waters. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Mangin, A.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Smith, B.; Alikas, K.; Arai, K.; Barbosa, C.; Bélanger, S.; Binding, C.; Bresciani, M.; et al. ACIX-Aqua: A Global Assessment of Atmospheric Correction Methods for Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 over Lakes, Rivers, and Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.A.; Simis, S.G.H.; Martinez-Vicente, V.; Poser, K.; Bresciani, M.; Alikas, K.; Spyrakos, E.; Giardino, C.; Ansper, A. Assessment of Atmospheric Correction Algorithms for the Sentinel-2A MultiSpectral Imager over Coastal and Inland Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 225, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, I.; Zibordi, G. AERONET-OC LWN Uncertainties: Revisited. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2023, 40, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q. Sensitivity Analysis of the Dark Spectrum Fitting Atmospheric Correction for Metre- and Decametre-Scale Satellite Imagery Using Autonomous Hyperspectral Radiometry. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 29948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.K.; Gurlin, D.; Pahlevan, N.; Alikas, K.; Conroy, T.; Anstee, J.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Barbosa, C.C.F.; Binding, C.; Bracher, A.; et al. GLORIA—A Globally Representative Hyperspectral in Situ Dataset for Optical Sensing of Water Quality. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, B.; Zibordi, G. On the Detectability of Adjacency Effects in Ocean Color Remote Sensing of Mid-Latitude Coastal Environments by SeaWiFS, MODIS-A, MERIS, OLCI, OLI and MSI. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibordi, G. Experimental Evaluation of Theoretical Sea Surface Reflectance Factors Relevant to Above-Water Radiometry. Opt. Express 2016, 24, A446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.R.; Ding, K. Self-shading of In-water Optical Instruments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1992, 37, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibordi, G.; Ferrari, G.M. Instrument Self-Shading in Underwater Optical Measurements: Experimental Data. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.B.; Zibordi, G. Platform Perturbations in Above-Water Radiometry. Appl. Opt. 2005, 44, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talone, M.; Zibordi, G. Spectral Assessment of Deployment Platform Perturbations in Above-Water Radiometry. Opt. Express 2019, 27, A878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HyperInSPACE Community Processor (HyperCP), GitHub. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/nasa/HyperCP/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Harmel, T.; Chami, M.; Tormos, T.; Reynaud, N.; Danis, P.-A. Sunglint Correction of the Multi-Spectral Instrument (MSI)-SENTINEL-2 Imagery over Inland and Sea Waters from SWIR Bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bailey, S.W. Correction of Sun Glint Contamination on the SeaWiFS Ocean and Atmosphere Products. Appl. Opt. 2001, 40, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roesler, C.S.; Perry, M.J. In Situ Phytoplankton Absorption, Fluorescence Emission, and Particulate Backscattering Spectra Determined from Reflectance. J. Geophys. Res. 1995, 100, 13279–13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, R.E.; Pahlevan, N.; Smith, B.; Boss, E.; Gurlin, D.; Alikas, K.; Kangro, K.; Kudela, R.M.; Vaičiūtė, D. A Hyperspectral Inversion Framework for Estimating Absorbing Inherent Optical Properties and Biogeochemical Parameters in Inland and Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, I.; Roca, M.; Santos-Echeandía, J.; Bernárdez, P.; Navarro, G. Use of the Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Satellites for Water Quality Monitoring: An Early Warning Tool in the Mar Menor Coastal Lagoon. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, A.; Ruddick, K.; Guerrero, R. Seasonal and Inter-Annual Turbidity Variability in the Río de La Plata from 15 Years of MODIS: El Niño Dilution Effect. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 182, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, F.P.; Haakonsson, S.; Ponce De León, L.; Bonilla, S.; Pedocchi, F. Challenges for Chlorophyll-a Remote Sensing in a Highly Variable Turbidity Estuary, an Implementation with Sentinel-2. Geocarto Int. 2023, 38, 2160017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.S.; Friedrichs, C.T.; Friedrichs, M.A.M. Long-Term Trends in Chesapeake Bay Remote Sensing Reflectance: Implications for Water Clarity. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2021, 126, e2021JC017959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llodrà-Llabrés, J.; Martínez-López, J.; Postma, T.; Pérez-Martínez, C.; Alcaraz-Segura, D. Retrieving Water Chlorophyll-a Concentration in Inland Waters from Sentinel-2 Imagery: Review of Operability, Performance and Ways Forward. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Fleck, J.; Pellerin, B.A.; Hansen, A.; Etheridge, A.; Foster, G.M.; Graham, J.L.; Bergamaschi, B.A.; Carpenter, K.D.; Downing, B.D.; et al. Field Techniques for Fluorescence Measurements Targeting Dissolved Organic Matter, Hydrocarbons, and Wastewater in Environmental Waters: Principles and Guidelines for Instrument Selection, Operation and Maintenance, Quality Assurance, and Data Reporting; USGS Techniques and Methods: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Sarkar, S.; Franz, B.A. Uncertainties in Coastal Ocean Color Products: Impacts of Spatial Sampling. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 181, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha, J.A.; Bracaglia, M.; Brando, V.E. Assessing the Influence of Different Validation Protocols on Ocean Colour Match-up Analyses. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 259, 112415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, E.J. In Vitro Determination of Chlorophylls a, b, C1 + C2 and Pheopigments in Marine and Freshwater Algae by Visible Spectrophotometry; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Arar, E.J.; Collins, G.B. In Vitro Determination of Chlorophyll a and Pheophytin a in Marine and Freshwater Algae by Fluorescence; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roesler, C.S.; Uitz, J.; Claustre, H.; Boss, E.; Xing, X.; Organelli, E.; Briggs, N.; Bricaud, A.; Schmechtig, C.; Poteau, A.; et al. Recommendations for Obtaining Unbiased Chlorophyll Estimates from in Situ Chlorophyll Fluorometers: A Global Analysis of WET Labs ECO Sensors. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2017, 15, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, B.D.; Pellerin, B.A.; Bergamaschi, B.A.; Saraceno, J.F.; Kraus, T.E.C. Seeing the Light: The Effects of Particles, Dissolved Materials, and Temperature on in Situ Measurements of DOM Fluorescence in Rivers and Streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2012, 10, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramski, D.; Woźniak, S.B. On the Role of Colloidal Particles in Light Scattering in the Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2005, 50, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, T.S.; Lambert, C.; Biggs, D.C. Distribution of Chlorophyll A and Phaeopigments in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico: A Comparison between Fluorometric and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Measurements. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1995, 56, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Trees, C.C.; Kennicutt, M.C.; Brooks, J.M. Errors Associated with the Standard Fluorimetric Determination of Chlorophylls and Phaeopigments. Mar. Chem. 1985, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilori, C.; Pahlevan, N.; Knudby, A. Analyzing Performances of Different Atmospheric Correction Techniques for Landsat 8: Application for Coastal Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Balasubramanian, S.; Sarkar, S.; Franz, B. Toward Long-Term Aquatic Science Products from Heritage Landsat Missions. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, A.; Gossn, J.; Vanhellemont, Q.; Ruddick, K. Detecting and Quantifying a Massive Invasion of Floating Aquatic Plants in the Río de La Plata Turbid Waters Using High Spatial Resolution Ocean Color Imagery. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG). Remote Sensing of Ocean Colour in Coastal, and Other Optically-Complex, Waters; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG): Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2000. Available online: https://www.ioccg.org/reports/report3.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Schröder, T.; Schmidt, S.I.; Kutzner, R.D.; Bernert, H.; Stelzer, K.; Friese, K.; Rinke, K. Exploring Spatial Aggregations and Temporal Windows for Water Quality Match-Up Analysis Using Sentinel-2 MSI and Sentinel-3 OLCI Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleratti, G.; Martinez-Vicente, V.; Atwood, E.C.; Simis, S.G.H.; Jackson, T. Validation of Full Resolution Remote Sensing Reflectance from Sentinel-3 OLCI across Optical Gradients in Moderately Turbid Transitional Waters. Front. Remote Sens. 2024, 5, 1359709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettle, M.; Brando, V.E.; Dekker, A.G. A Methodology for Retrieval of Environmental Noise Equivalent Spectra Applied to Four Hyperion Scenes of the Same Tropical Coral Reef. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.M.; Simis, S.G.H.; Selmes, N.; Sent, G.; Ienna, F.; Martinez-Vicente, V. Spatial Structure of in Situ Reflectance in Coastal and Inland Waters: Implications for Satellite Validation. Front. Remote Sens. 2023, 4, 1249521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, S.L.; Forrest, A.L.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Jin, Y.; Cortés, A.; Schladow, S.G. Quantifying Scales of Spatial Variability of Cyanobacteria in a Large, Eutrophic Lake Using Multiplatform Remote Sensing Tools. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 612934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, T.; Behnert, I.; Schaale, M.; Fischer, J.; Doerffer, R. Atmospheric Correction Algorithm for MERIS above Case-2 Waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 1469–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, K.G.; De Cauwer, V.; Park, Y.-J.; Moore, G. Seaborne Measurements of near Infrared Water-Leaving Reflectance: The Similarity Spectrum for Turbid Waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006, 51, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Franz, B.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Bailey, S.W. Multiband Atmospheric Correction Algorithm for Ocean Color Retrievals. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Remote Sensing of the Ocean Contributions from Ultraviolet to Near-Infrared Using the Shortwave Infrared Bands: Simulations. Appl. Opt. 2007, 46, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Son, S.; Shi, W. Evaluation of MODIS SWIR and NIR-SWIR Atmospheric Correction Algorithms Using SeaBASS Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, W.; Jiang, L. Atmospheric Correction Using Near-Infrared Bands for Satellite Ocean Color Data Processing in the Turbid Western Pacific Region. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, K.G.; Ovidio, F.; Rijkeboer, M. Atmospheric Correction of SeaWiFS Imagery for Turbid Coastal and Inland Waters. Appl. Opt. 2000, 39, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.A.; Wang, M.; Maritorena, S.; Robinson, W. Atmospheric Correction of Satellite Ocean Color Imagery: The Black Pixel Assumption. Appl. Opt. 2000, 39, 3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werdell, P.J.; Franz, B.A.; Bailey, S.W. Evaluation of Shortwave Infrared Atmospheric Correction for Ocean Color Remote Sensing of Chesapeake Bay. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2238–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimitsis, D.G.; Retalis, A.; Clayton, C.R.I. The Assessment of Atmospheric Pollution Using Satellite Remote Sensing Technology in Large Cities in the Vicinity of Airports. In Urban Air Quality—Recent Advances; Sokhi, R.S., Bartzis, J.G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 631–640. ISBN 978-94-010-3935-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhellemont, Q.; Ruddick, K. Atmospheric Correction of Sentinel-3/OLCI Data for Mapping of Suspended Particulate Matter and Chlorophyll-a Concentration in Belgian Turbid Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, M. Identification of Pixels with Stray Light and Cloud Shadow Contaminations in the Satellite Ocean Color Data Processing. Appl. Opt. 2013, 52, 6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Ocean Color, Accepted Changes to Masks and Flags. Available online: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/reprocessing/r2002/seawifs/masks_n_flags/#SEC5 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Hommersom, A. Technical Report about Measurement Protocols; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Vanhellemont, Q. A Generalized Physics-Based Correction for Adjacency Effects. Appl. Opt. 2025, 64, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, A.; Prieur, L. Analysis of Variations in Ocean Color1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingas, M.; Brown, C. A Review of Oil Spill Remote Sensing. Sensors 2017, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurin, D.A.; Dierssen, H.M. Advantages and Limitations of Ocean Color Remote Sensing in CDOM-Dominated, Mineral-Rich Coastal and Estuarine Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 125, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Lu, Y.; Sun, S.; Liu, Y. Optical Remote Sensing of Oil Spills in the Ocean: What Is Really Possible? J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021, 9141902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.S.; Fall, K.A.; Friedrichs, C.T. Clarifying Water Clarity: A Call to Use Metrics Best Suited to Corresponding Research and Management Goals in Aquatic Ecosystems. Limnol. Ocean. Lett. 2023, 8, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaneveld, J.R.V.; Kitchen, J.C.; Moore, C.C. Scattering Error Correction of Reflecting-Tube Absorption Meters. In Proceedings of the Ocean Optics XII, Bergen, Norway, 13–15 June 1994; pp. 44–55, Volume 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.M.; Twardowski, M.S.; Zaneveld, J.R.V.; Moore, C.M.; Barnard, A.H.; Donaghay, P.L.; Rhoades, B. Hyperspectral Temperature and Salt Dependencies of Absorption by Water and Heavy Water in the 400–750 Nm Spectral Range. Appl. Opt. 2006, 45, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, I.; Twardowski, M.; Roesler, C.S.; Röttgers, R.; Stramski, D.; McKee, D.; Tonizzo, A.; Drapeau, S. Hyperspectral Optical Absorption Closure Experiment in Complex Coastal Waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2021, 19, 589–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaneveld, J.R.V.; Kitchen, J.C.; Bricaud, A.; Moore, C.C. Analysis of In-Situ Spectral Absorption Meter Data. In Proceedings of the Ocean Optics XI, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–22 July 1992; pp. 187–200, Volume 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, D.; Piskozub, J.; Brown, I. Scattering Error Corrections for in Situ Absorption and Attenuation Measurements. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 19480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röttgers, R.; McKee, D.; Woźniak, S.B. Evaluation of Scatter Corrections for Ac-9 Absorption Measurements in Coastal Waters. Methods Oceanogr. 2013, 7, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockley, N.D.; Röttgers, R.; McKee, D.; Lefering, I.; Sullivan, J.M.; Twardowski, M.S. Assessing Uncertainties in Scattering Correction Algorithms for Reflective Tube Absorption Measurements Made with a WET Labs Ac-9. Opt. Express 2017, 25, A1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, D.; Piskozub, J.; Röttgers, R.; Reynolds, R.A. Evaluation and Improvement of an Iterative Scattering Correction Scheme for in Situ Absorption and Attenuation Measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 1527–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fry, E.S.; Kattawar, G.W.; Pope, R.M. Integrating Cavity Absorption Meter. Appl. Opt. 1992, 31, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, J.T.O. Modeling the Performance of an Integrating-Cavity Absorption Meter: Theory and Calculations for a Spherical Cavity. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, M.; Thirouard, A.; Harmel, T. POLVSM (Polarized Volume Scattering Meter) Instrument: An Innovative Device to Measure the Directional and Polarized Scattering Properties of Hydrosols. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 26403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.M.; Twardowski, M.S. Angular Shape of the Oceanic Particulate Volume Scattering Function in the Backward Direction. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, Y.; He, M.-X. Calibration of the LISST-VSF to Derive the Volume Scattering Functions in Clear Waters. Opt. Express 2019, 27, A1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fournier, G.R.; Gray, D.J. Interpretation of Scattering by Oceanic Particles around 120 Degrees and Its Implication in Ocean Color Studies. Opt. Express 2017, 25, A191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, E.; Pegau, W.S. Relationship of Light Scattering at an Angle in the Backward Direction to the Backscattering Coefficient. Appl. Opt. 2001, 40, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, D.R.; Maffione, R.A. Determining the Backward Scattering Coefficient with Fixed-Angle Backscattering Sensors Revisited. In Proceedings of the Ocean Optics XVI, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 18–22 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, T. Significant Relationship between the Backward Scattering Coefficient of Sea Water and the Scatterance at 120°. Appl. Opt. 1990, 29, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chami, M.; Marken, E.; Stamnes, J.J.; Khomenko, G.; Korotaev, G. Variability of the Relationship between the Particulate Backscattering Coefficient and the Volume Scattering Function Measured at Fixed Angles. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, 2005JC003230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, R.; Christensen, V.G.; Graham, J.L.; Rogosch, J.S.; Rosen, B.H. Toxic Algae in Inland Waters of the Conterminous United States—A Review and Synthesis. Water 2023, 15, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, F.R. Blooming Algae: A Canadian Perspective on the Rise of Toxic Cyanobacteria. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 73, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxaran, D.; Leymarie, E.; Nechad, B.; Dogliotti, A.; Ruddick, K.; Gernez, P.; Knaeps, E. Improved Correction Methods for Field Measurements of Particulate Light Backscattering in Turbid Waters. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Chin Liew, S.; Wong, E. Simple Method to Extend the Range of ECO-BB for Waters with High Backscattering Coefficient. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrisk, G.; Drayson, N.; Ford, P.; Botha, H.; Anstee, J. Performance Assessment of Serial Dilutions for the Determination of Backscattering Properties in Highly Turbid Waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2023, 21, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WET Labs, Inc. Scattering Meter ECO-BB User’s Guide. 2007. Available online: https://www.comm-tec.com/prods/mfgs/Wetlabs/Manuals/Eco-BB_manual.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- HOBI Labs. HydroScat-6P Series 300 Spectral Backscattering Sensor & Fluorometer User’s Manual. 2014. Available online: https://www.hobiservices.com/docs/HS6ManualRevL-2014-7.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Werdell, P.J.; Bailey, S.; Fargion, G.; Pietras, C.; Knobelspiesse, K.; Feldman, G.; McClain, C. Unique Data Repository Facilitates Ocean Color Satellite Validation. EoS Trans. 2003, 84, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogashawara, I. Bibliometric Analysis of Remote Sensing of Inland Waters Publications from 1985 to 2020. Geographies 2021, 1, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean Optics Class—Calibration & Validation for Ocean Color Remote Sensing. Available online: https://misclab.umeoce.maine.edu/OceanOpticsClass2023/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Applied Remote Sensing Training Program. Available online: http://appliedsciences.nasa.gov/what-we-do/capacity-building/arset (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG). Lecture Material from IOCCG Training Courses. Available online: https://ioccg.org/what-we-do/training-and-education/lectures/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Ocean Optics Class 2023 Resources. Available online: https://misclab.umeoce.maine.edu/OceanOpticsClass2023/resources/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Ocean Optics Web Book. Available online: https://www.oceanopticsbook.info/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Ramírez-Castañeda, V. Disadvantages in Preparing and Publishing Scientific Papers Caused by the Dominance of the English Language in Science: The Case of Colombian Researchers in Biological Sciences. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CEOS Analysis Ready Data. Available online: https://ceos.org/ard/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Muir, J. Building Trust in Earth Observation Satellites and Imagery. Spiral Blue Seminar Series, 2021. Available online: https://portal.ogc.org/files/?artifact_id=97952 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Djenontin, I.N.S.; Meadow, A.M. The Art of Co-Production of Knowledge in Environmental Sciences and Management: Lessons from International Practice. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howarth, C.; Monasterolo, I. Opportunities for Knowledge Co-Production across the Energy-Food-Water Nexus: Making Interdisciplinary Approaches Work for Better Climate Decision Making. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, C.J.; Carmen Lemos, M.; Dessai, S. Actionable Knowledge for Environmental Decision Making: Broadening the Usability of Climate Science. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2013, 38, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weko, S.; Goldthau, A. Bridging the Low-Carbon Technology Gap? Assessing Energy Initiatives for the Global South. Energy Policy 2022, 169, 113192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor | Satellite Agency Region | Orbit | Spatial Resolution (m) | Spectral Resolution (nm) | Temporal Resolution | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI | HIMAWARI-8 JMA Japan | Geostationary | 1000–2000 | 470–1331 (16 bands) | 10 min | Meteorological Satellite Center (MSC)|HOME (https://www.data.jma.go.jp/mscweb/en/index.html) |

| AHI | HIMAWARI-9 JAXA Japan | Geostationary | 1000–2000 | 470–1331 (16 bands) | 10 min | Meteorological Satellite Center (MSC)|HOME (https://www.data.jma.go.jp/mscweb/en/index.html) |

| GOCI-II | GeoKompsat-2B KARI/KIOST South Korea | Geostationary | 250 | 380–900 | 10 times per day | Korea Ocean Satellite Center (https://kosc.kiost.ac.kr/index.nm?menuCd=44&lang=en) |

| HYC | PRISMA ASI Italy | Polar | 30 | 400–1010 (hyperspectral, 66 bands), and 920–2505 (hyperspectral, 173 bands) | User-defined targets | ASI|Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (https://www.asi.it/en/earth-science/prisma/) |

| MSI | Sentinel-2A/B/C ESA EU | Polar | 10–20-60 | 442–2202 (13 bands) | 10 days | Sentinel-2|Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/data-collections/copernicus-sentinel-data/sentinel-2) |

| MODIS | Aqua (EOS-PM1) NASA USA | Polar | 250–1000 | 405–2130 (13 bands) | 1 day | MODIS Web (https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/) |

| MODIS | Terra (EOS-PM2) NASA USA | Polar | 250–1000 | 405–2130 (13 bands) | 1 day | MODIS Web (https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/) |

| OCI | PACE NASA USA | Polar | 1000 | 317–885, 1240–2250 nm (hyperspectral, 5 nm spacing) | 1 day | NASA PACE - Home (https://pace.gsfc.nasa.gov/) |

| OCM | Oceansat-2 ISRO India | Polar | 360 × 236 | 404–885 (8 bands) | 2 days | Oceansat-2 (https://www.isro.gov.in/Oceansat_2.html) |

| OCM | EOS-6-Oceansat-3 ISRO India | Polar | 360/1080 | 412–1010 (13 bands) | 2 days | EOS-06 (https://www.isro.gov.in/EOS_06.html) |

| EnMAP | Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program DLR-EOC Germany | Polar | 30 | 420–1000 (hyperspectral 6.5 nm spacing) 900–2450 (hyperspectral 10 nm spacing) | 27 days | EnMAP (https://www.enmap.org/) |

| PMC-2 | Gaofen-2 CRESDA China | Polar | Sub-meter | Multispectral (4 bands VIS-NIR) | 5 days | Earth Observation Satellites from CRESDA (https://database.eohandbook.com/database/agencysummary.aspx?agencyID=130) |

| OLCI | Sentinel-3A/B ESA/EUMETSATEU | Polar | 300 | 400–1020 (16 bands) | 2 days | Sentinel-3|EUMETSAT (https://www.eumetsat.int/sentinel-3) |

| OLI | LandSat-8 NASA/USGS USA | Polar | 30 | 442–2200 (9 bands) | 16 days | Landsat 8|U.S. Geological Survey (https://www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions/landsat-8) |

| OLI-2 | LandSat-9 NASA/USGS USA | Polar | 30 | 442–2200 (9 bands) | 16 days | Landsat 9|U.S. Geological Survey (https://www.usgs.gov/landsat-missions/landsat-9) |

| SGLI | GCOM-C JAXA Japan | Polar | 250–1000 | 375–12,500 (19 bands) | 2–3 days | JAXA|Global Change Observation Mission - Climate “SHIKISAI” (GCOM-C) (https://global.jaxa.jp/projects/sat/gcom_c/) |

| VIIRS | Suomi NPP NOAA USA | Polar | 375/750 | 412–11,800 (22 bands) | 1 day | Joint Polar Satellite System|NESDIS|National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/our-satellites/currently-flying/joint-polar-satellite-system) |

| VIIRS | JPSS-1/NOAA-20 NOAA/NASA USA | Polar | 375/750 | 412–11,800 (22 bands) | 1 day | Joint Polar Satellite System|NESDIS|National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/our-satellites/currently-flying/joint-polar-satellite-system) |

| VIIRS | JPSS-2/NOAA-21 NOAA/NASA USA | Polar | 375/750 | 412–11,800 (22 bands) | 1 day | Joint Polar Satellite System|NESDIS|National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/our-satellites/currently-flying/joint-polar-satellite-system) |

| COCTS | HY-1C/1D NSOAS/MNR China | Polar | 1000 | 412–1200 (10 bands) | 1 day | HY-1C/1D (HaiYang-1C/1D) - eoPortal (https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/hy-1c-1d#eop-quick-facts-section) |

| CZI | HY-1C/1D NSOAS/MNR China | Polar | 50 | 460–825 (5 bands) | 1 day | HY-1C/1D (HaiYang-1C/1D) - eoPortal (https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/hy-1c-1d#eop-quick-facts-section) |

| Symbol/Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| a | Absorption coefficient |

| aCDOM | Absorption coefficient of CDOM |

| aNAP | Absorption coefficient of non-algal particles |

| anw | Non-water absorption coefficient |

| ap | Absorption coefficient of suspended particles (phytoplankton + NAP) |

| aphy | Absorption coefficient of phytoplankton |

| AOP | Apparent Optical Property |

| b | Scattering coefficient |

| bb | Backscattering coefficient |

| bbp | Backscattering coefficient of suspended particles |

| bnw | Non-water scattering coefficient |

| c | Beam attenuation |

| CDOM | Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter |

| Chl a | Chlorophyll a concentration |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| Ed | Downwelling irradiance |

| HAB | Harmful Algal Bloom |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IOP | Inherent Optical Property |

| Kd | Diffuse attenuation coefficient of downwelling irradiance |

| KPAR | Diffuse attenuation coefficient of photosynthetically active radiation |

| Lw | Upwelling (water-leaving) radiance |

| NAP | Non-Algal Particles |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NPQ | Non-Photochemical Quenching |

| PC | Phycocyanin |

| PCC | Phytoplankton Community Composition |

| PE | Phycoerythrin |

| Rrs | Remote sensing reflectance |

| SPM/TSS | Suspended Particulate Matter/Total Suspended Solids |

| SWIR | Shortwave Infrared |

| VIS | Visible spectrum |

| VSF or β | Volume scattering function |

| βp | Particulate volume scattering function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avouris, D.M.; Maciel, F.; Sharp, S.L.; Craig, S.E.; Dekker, A.G.; Di Vittorio, C.A.; Gardner, J.R.; Goldsmith, E.; Gossn, J.I.; Greb, S.R.; et al. Advancements in Satellite Observations of Inland and Coastal Waters: Building Towards a Global Validation Network. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244008

Avouris DM, Maciel F, Sharp SL, Craig SE, Dekker AG, Di Vittorio CA, Gardner JR, Goldsmith E, Gossn JI, Greb SR, et al. Advancements in Satellite Observations of Inland and Coastal Waters: Building Towards a Global Validation Network. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244008

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvouris, Dulcinea M., Fernanda Maciel, Samantha L. Sharp, Susanne E. Craig, Arnold G. Dekker, Courtney A. Di Vittorio, John R. Gardner, Emma Goldsmith, Juan I. Gossn, Steven R. Greb, and et al. 2025. "Advancements in Satellite Observations of Inland and Coastal Waters: Building Towards a Global Validation Network" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244008

APA StyleAvouris, D. M., Maciel, F., Sharp, S. L., Craig, S. E., Dekker, A. G., Di Vittorio, C. A., Gardner, J. R., Goldsmith, E., Gossn, J. I., Greb, S. R., Grunert, B. K., Gurlin, D., Jampani, M., Khan, R. M., Lowin, B., McKinna, L., Mouw, C. B., Ogashawara, I., Rivero Calle, S., ... Werdell, J. (2025). Advancements in Satellite Observations of Inland and Coastal Waters: Building Towards a Global Validation Network. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244008