A Distributed Data Management and Service Framework for Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Observations

Highlights

- We present DDMS, a distributed data management and service framework that consolidates heterogeneous remote sensing data sources, including optical imagery and InSAR point clouds, into a unified system for scalable and efficient management.

- The framework introduces an integrated storage model combining distributed file systems, NoSQL, and relational databases, alongside a parallel computing model, enabling optimized performance for large-scale image processing and real-time data access.

- DDMS significantly enhances the scalability and efficiency of remote sensing data management, providing a flexible solution for real-time service delivery in applications that require high-volume, diverse datasets such as disaster monitoring, environmental analysis, and urban development.

- By incorporating elastic parallelism and modular design, DDMS supports dynamic, large-scale geospatial data processing, reducing latency, improving service responsiveness, and ensuring robust performance across varying workloads and data sizes.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. DDMS Management and Service Architecture

2.1. The Overall Architecture of DDMS

2.2. Remote Sensing Data Integrated Storage Model

2.3. Remote Sensing Data Distributed Processing Model

3. DDMS Application Design: Optical Image Service Management and Large-Scale InSAR Data Visualization

3.1. Optical Image Service Online Management

| Algorithm 1 Parallel update of the remote sensing image tile service |

| Input: HTTP update request R |

| Output: Resulting tile(s) T |

| 1: if isValidFormat(R) then |

| 2: forwardRequest(R) |

| 3: end if |

| 4: (z, x, y) parseTileRequest(R) |

| 5: targetBox computeSpatialBox(z, x, y) |

| 6: InfoList |

| 7: for each sourceImage S in updateCandidates do // parallelizable |

| 8: (zs, xs, ys) parseImageHeader(S) |

| 9: box_s computeSpatialBox(zs, xs, ys) |

| 10: if intersects(box_s, targetBox) then |

| 11: InfoList InfoList retrieveImageInfo(box_s) |

| 12: end if |

| 13: end for |

| 14: TileSet |

| 15: for each info in InfoList do // parallelizable |

| 16: tile readTileFromStore(info, NoSQLHandler) |

| 17: TileSet TileSet {tile} |

| 18: end for |

| 19: if |TileSet| = 0 then |

| 20: return null |

| 21: else if |TileSet| = 1 then |

| 22: return head(TileSet) |

| 23: else |

| 24: T TileSet.reduce { (A, B) |

| 25: for each band b in B do |

| 26: for r = 1 to rows(b) do |

| 27: for c = 1 to cols(b) do |

| 28: A[b][r][c] ← mergeResample(A[b][r][c], B[b][r][c], method) |

| 29: end for |

| 30: end for |

| 31: end for |

| 32: A |

| 33: } |

| 34: return T |

| 35: end if |

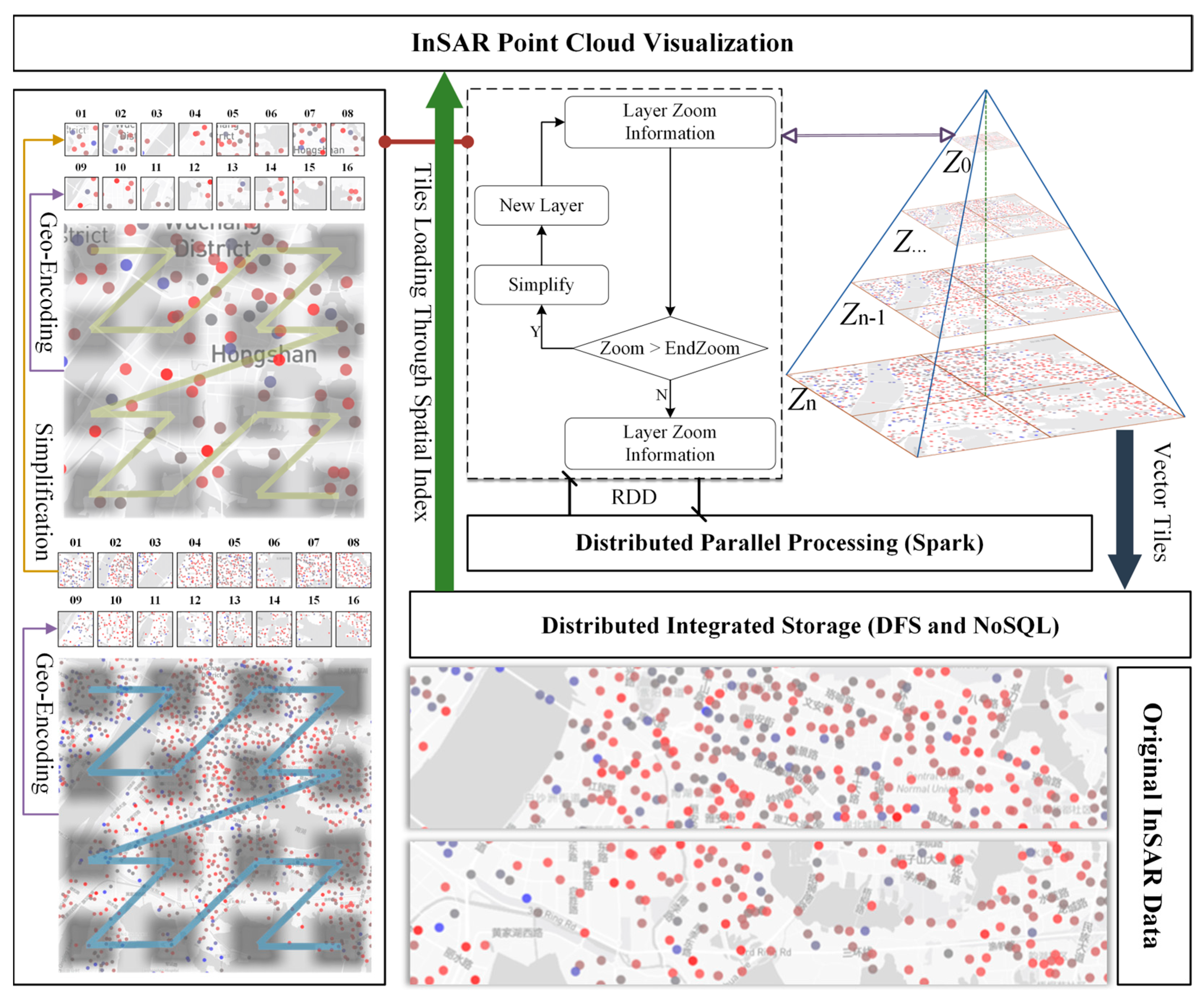

3.2. Large-Scale InSAR Point Cloud Visualization

4. Experiments and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Setting

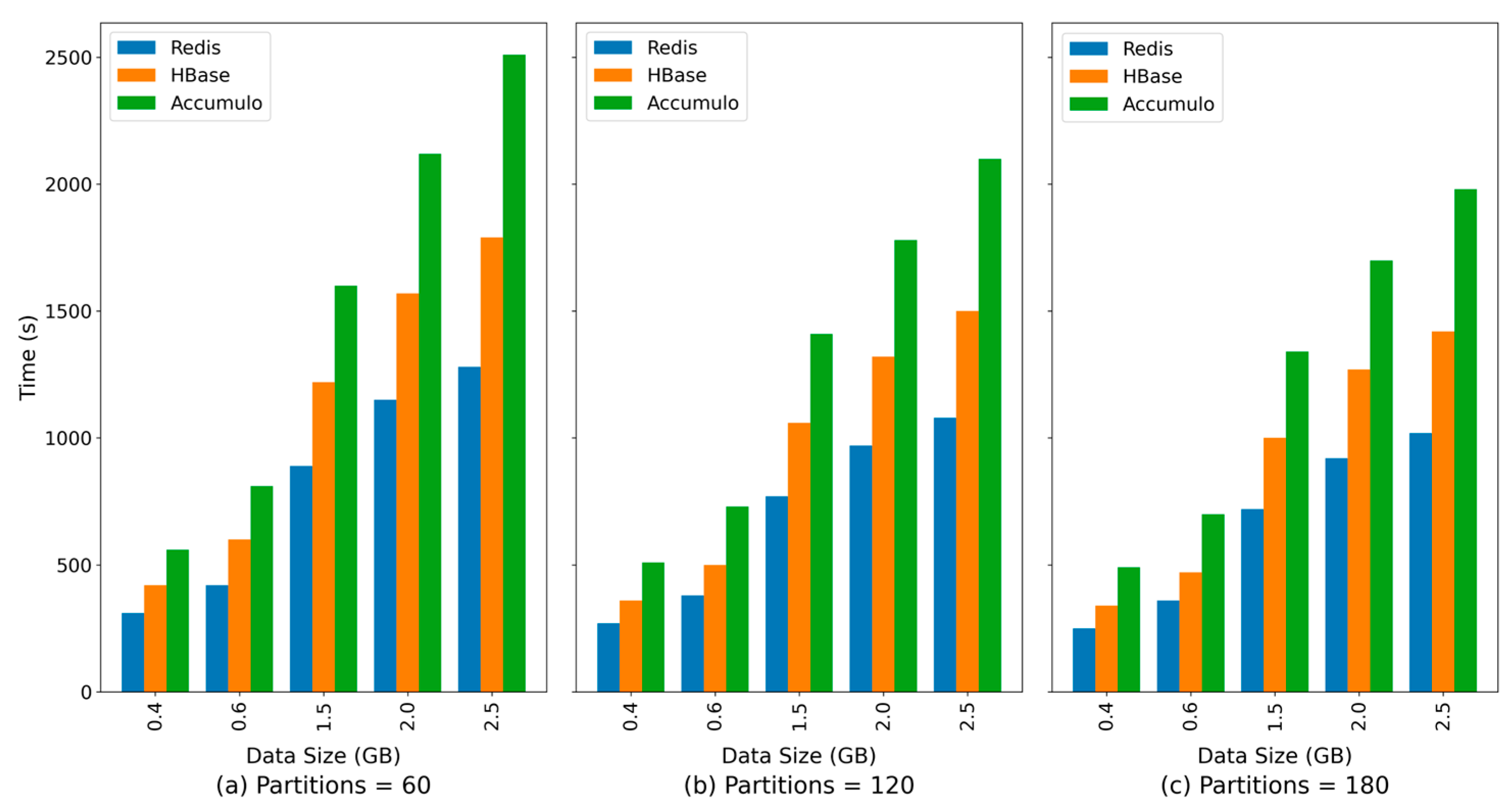

4.2. Experiments on Storage Capability

4.3. Experiments on Image Service Construction Performance

4.4. Experiments on Stress Testing for Service Responsiveness

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Remote Sensing and Geospatial Analysis in the Big Data Era: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Fang, C. Urban Remote Sensing with Spatial Big Data: A Review and Renewed Perspective of Urban Studies in Recent Decades. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, J. Geological Remote Sensing Interpretation via a Local-to-Global Sensitive Feature Fusion Network. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 135, 104258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, S.; Iliev, M.; Borisova, B.; Semerdzhieva, L.; Petrov, S. A Methodological Framework for High-Resolution Surface Urban Heat Island Mapping: Integration of UAS Remote Sensing, GIS, and the Local Climate Zoning Concept. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Chowdhury, T.; Murphy, R.R.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Rahnemoonfar, M. SAM-VQA: Supervised Attention-Based Visual Question Answering Model for Post-Disaster Damage Assessment on Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Gong, W. Impact Assessment of Flood Events Based on Multisource Satellite Remote Sensing: The Case of Kahovka Dam. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 20164–20176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.; Mleczko, M.M.; Brewin, R.J.W.; Gaston, K.J.; Mueller, M.; Shutler, J.D.; Yan, X.; Anderson, K. Environmental Impacts of Earth Observation Data in the Constellation and Cloud Computing Era. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, X.X. Vision-Language Models in Remote Sensing: Current Progress and Future Trends. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2024, 12, 32–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Guo, J.; Zimmer-Dauphinee, J.R.; Nieusma, J.M.; Wang, X.; VanValkenburgh, P.; Wernke, S.A.; Huo, Y. Vision Foundation Models in Remote Sensing: A Survey. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 13, 190–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadzadegan, F.; Toosi, A.; Dadrass Javan, F. A Critical Review on Multi-Sensor and Multi-Platform Remote Sensing Data Fusion Approaches: Current Status and Prospects. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 1327–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Plaza, A.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Sun, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhu, Y. Big Data for Remote Sensing: Challenges and Opportunities. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Mei, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, D. Efficient Storage Method for Massive Remote Sensing Image via Spark-Based Pyramid Model. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control 2017, 13, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Du, X.; Fan, X.; Giuliani, G.; Hu, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, J.; et al. Cloud-Based Storage and Computing for Remote Sensing Big Data: A Technical Review. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 1417–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, W.; Qiang, X.; Zheng, J.; Huang, F. Research on Remote Sensing Image Storage Management and a Fast Visualization System Based on Cloud Computing Technology. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 59861–59886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, X.; Ding, Z.; Wei, Z.; Plaza, J.; Plaza, A. An Efficient and Scalable Framework for Processing Remotely Sensed Big Data in Cloud Computing Environments. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4294–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. From Observation to Understanding: Rethinking Geological Hazard Research in an Era of Advanced Technologies. npj Nat. Hazards 2025, 2, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, D.S.; Brannock, J.; Dissen, J.; Keown, P.; Szura, K.; Brown, O.B.; Simonson, A. NOAA Open Data Dissemination: Petabyte-Scale Earth System Data in the Cloud. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velastegui-Montoya, A.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Rivera-Torres, H.; Sadeck, L.; Adami, M. Google Earth Engine: A Global Analysis and Future Trends. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Lyapustin, A.; Wang, Y.; Tucker, C.J.; Khan, M.N.; Policelli, F.; Neigh, C.S.R.; Hall, A.A. Calibration of Maxar Constellation Over Libya-4 Site Using MAIAC Technique. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 5460–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, V.C.F.; Queiroz, G.R.; Ferreira, K.R. An Overview of Platforms for Big Earth Observation Data Management and Analysis. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Nisar, M.; Pauciullo, A.; Imperatore, P.; Lapegna, M.; Romano, D. A Multi-Level Parallel Algorithm for Detection of Single Scatterers in SAR Tomography. In Proceedings of the 2025 33rd Euromicro International Conference on Parallel, Distributed, and Network-Based Processing (PDP), Turin, Italy, 12 March 2025; IEEE: NewYork, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 544–551. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, U.; Singh, Y.K.; Prabhu, T.S.M.; Yendargaye, G.; Kale, R.; Khare, M.K.; Kumar, B.; Panchang, R. Embankment Breach Simulation and Inundation Mapping Leveraging High-Performance Computing for Enhanced Flood Risk Prediction and Assessment. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, X-3–2024, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Huang, B.; Ranjan, R.; Zomaya, A.; Jie, W. Remote Sensing Big Data Computing: Challenges and Opportunities. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2015, 51, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, R.; Pritchard, H.; Ghafoor, S. Evaluation of a Dynamic Resource Management Strategy for Elastic Scientific Workflows. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Parallel Processing, Madrid, Spain, 26–30 August 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 334–345. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, R.; Pritchard, H.; Ghafoor, S. Enabling Elasticity in Scientific Workflows for High-Performance Computing Systems. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Parallel Processing, Dresden, Germany, 25–29 August 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, A.; Rezaei, M.; Laure, E.; Tordsson, J. Hybrid Resource Management for HPC and Data Intensive Workloads. In Proceedings of the 2019 19th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID), Larnaca, Cyprus, 14–17 May 2019; IEEE: NewYork, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Vanz, N.; Munhoz, V.; Castro, M.; Pilla, L.L.; Aumage, O. Task-Based HPC in the Cloud: Price-Performance Analysis of N-Body Simulations with StarPU. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering IC2E 2025, Rennes, France, 23–26 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhuraibi, Y.; Paraiso, F.; Djarallah, N.; Merle, P. Elasticity in Cloud Computing: State of the Art and Research Challenges. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2017, 11, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiang, L.; Yue, P.; Gong, J.; Wu, H. Open Geospatial Engine: A Cloud-Based Spatiotemporal Computing Platform. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, X-4–2024, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cao, Z.; Yue, P.; Zhang, C. Earth Video Cube: A Geospatial Data Cube for Multisource Earth Observation Video Management and Analysis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4986–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Du, X.; Yan, Z.; Fan, X. ScienceEarth: A Big Data Platform for Remote Sensing Data Processing. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gu, M.; Shi, G.; Hu, Y.; Xie, M. Distribution-Based Approach for Efficient Storage and Indexing of Massive Infrared Hyperspectral Sounding Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gan, W.; Chao, H.-C.; Yu, P.S. Geospatial Big Data: Survey and Challenges. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 17007–17020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yao, X.; Liu, D.; Zhao, L.; Li, L.; Zhu, D.; Li, G. A Ceph-Based Storage Strategy for Big Gridded Remote Sensing Data. Big Earth Data 2022, 6, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, S.; Maleki, N.; Olsson, T.; Ahlgren, F.; Seyednezhad, M.; Berahmand, K. MapReduce Scheduling Algorithms in Hadoop: A Systematic Study. J. Cloud Comput. 2023, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, W.; Han, W.; Huang, X.; Long, A.; Wang, Y. Remote Sensing Thematic Product Generation for Sustainable Development of the Geological Environment. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, I.A.T.; Anuar, N.B.; Marjani, M.; Ahmed, E.; Chiroma, H.; Firdaus, A.; Abdullah, M.T.; Alotaibi, F.; Ali, W.K.M.; Yaqoob, I. MapReduce Scheduling Algorithms: A Review. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 4915–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, C.; Hou, J. A Scalable Computing Resources System for Remote Sensing Big Data Processing Using GeoPySpark Based on Spark on K8s. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldawy, A.; Mokbel, M.F. SpatialHadoop: A MapReduce Framework for Spatial Data. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 31st International Conference on Data Engineering, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 13–17 April 2015; pp. 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, A.; Wang, F.; Vo, H.; Lee, R.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Saltz, J. Hadoop-GIS: A High Performance Spatial Data Warehousing System over MapReduce. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2013, 6, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wu, J.; Sarwat, M. A Demonstration of GeoSpark: A Cluster Computing Framework for Processing Big Spatial Data. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Helsinki, Finland, 16–20 May 2016; pp. 1410–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F. A Spark Based Computing Framework For Spatial Data. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, IV-4/W2, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Yu, Y.; Malluhi, Q.M.; Ouzzani, M.; Aref, W.G. LocationSpark: A Distributed in-Memory Data Management System for Big Spatial Data. In Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment; VLDB Endowment, New Delhi, India, 5 September–9 September 2016; Volume 9, pp. 1565–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, P.; Zhang, X.; Ye, G. Efficient Management and Processing of Massive InSAR Images Using an HPC-Based Cloud Platform. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 2866–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, R.; Liu, X. Research on General System of Remote Sensing Satellite Data Preprocessing Based on MPI + CUDA. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Geology, Mapping and Remote Sensing (ICGMRS), Zhoushan, China, 22 April 2022; IEEE: NewYork, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 607–612. [Google Scholar]

- Haut, J.M.; Paoletti, M.E.; Moreno-Alvarez, S.; Plaza, J.; Rico-Gallego, J.-A.; Plaza, A. Distributed Deep Learning for Remote Sensing Data Interpretation. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1320–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, A.; Schreiber, M.; Cascajo, A.; Besnard, J.-B.; Vef, M.-A.; Huber, D.; Happ, S.; Brinkmann, A.; Singh, D.E.; Hoppe, H.-C.; et al. Malleability in Modern HPC Systems: Current Experiences, Challenges, and Future Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2024, 35, 1551–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Lei, X.; Wang, L. Distributed Fusion of Heterogeneous Remote Sensing and Social Media Data: A Review and New Developments. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, J.; Meng, X. RSIMS: Large-Scale Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Images Management System. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Du, X.; Fan, X.; Yan, Z.; Kang, X.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z. A Modular Remote Sensing Big Data Framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Su, H.; Gu, Z.; Wang, L. Efficient Management and Scheduling of Massive Remote Sensing Image Datasets. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, A.; Mühlbauer, M.; Heinen, T.; Böck, M.; Munteanu, R.; D’Amore, M.; Riedlinger, T.; Roatsch, T.; Strunz, G.; Helbert, J. Approach towards a Holistic Management of Research Data in Planetary Science—Use Case Study Based on Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar-Martos, J.A.; Rueda-Ruiz, A.J.; Ogayar-Anguita, C.J.; Segura-Sánchez, R.J.; López-Ruiz, A. Strategies for the Storage of Large LiDAR Datasets—A Performance Comparison. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, R.A.; Surin, E.S.M.; Sarker, M.R. A Systematic Review of Automated Classification for Simple and Complex Query SQL on NoSQL Database. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2024, 48, 1405–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokugam Hewage, C.N.; Laefer, D.F.; Vo, A.-V.; Le-Khac, N.-A.; Bertolotto, M. Scalability and Performance of LiDAR Point Cloud Data Management Systems: A State-of-the-Art Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriki Semlali, B.-E.; Freitag, F. SAT-Hadoop-Processor: A Distributed Remote Sensing Big Data Processing Software for Earth Observation Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Huang, X.; He, X.; Deng, Z.; Chen, Y. R-MLGTI: A Grid- and R-Tree-Based Hybrid Index for Unevenly Distributed Spatial Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, M.; Hugenholtz, C.H. Remote Sensing of Natural Hazard-Related Disasters with Small Drones: Global Trends, Biases, and Research Opportunities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 264, 112577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, H.; Rani, S.; Soni, M.; Keshta, I.; Prasad, K.D.V.; Shabaz, M. Integrating Remote Sensing and Geospatial AI-Enhanced ISAC Models for Advanced Localization and Environmental Monitoring. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, D.; Xu, J.; Xia, Z.; Hao, H.; Chen, Z. A Twenty-Years Remote Sensing Study Reveals Changes to Alpine Pastures under Asymmetric Climate Warming. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, G.V.; Aykanat, C. Scaling Sparse Matrix-Matrix Multiplication in the Accumulo Database. Distrib. Parallel Databases 2020, 38, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Dong, H.; Wei, Y.; Liu, S.; Du, D.H.C. Is-Hbase: An in-Storage Computing Optimized Hbase with i/o Offloading and Self-Adaptive Caching in Compute-Storage Disaggregated Infrastructure. ACM Trans. Storage 2022, 18, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopade, R.; Pachghare, V. A Data Recovery Technique for Redis Using Internal Dictionary Structure. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2021, 38, 301218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Qi, R.; Tsai, Q.; Lin, S.; Dong, F.; Li, K.; Li, K. Parallel Algorithm Design and Optimization of Geodynamic Numerical Simulation Application on the Tianhe New-Generation High-Performance Computer. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, S.; Masterov, M.V.; Padding, J.T.; Buist, K.A.; Baltussen, M.W.; Kuipers, J.A.M. Parallelization of a Stochastic Euler-Lagrange Model Applied to Large Scale Dense Bubbly Flows. J. Comput. Phys. X 2020, 8, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, H.; Wu, H.; Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Qi, K.; Gong, J.; Xiang, L.; Cao, Y. A Distributed Data Management and Service Framework for Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Observations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244009

Cheng H, Wu H, Zheng J, Li Z, Qi K, Gong J, Xiang L, Cao Y. A Distributed Data Management and Service Framework for Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Observations. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244009

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Hongquan, Huayi Wu, Jie Zheng, Zhenqiang Li, Kunlun Qi, Jianya Gong, Longgang Xiang, and Yipeng Cao. 2025. "A Distributed Data Management and Service Framework for Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Observations" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244009

APA StyleCheng, H., Wu, H., Zheng, J., Li, Z., Qi, K., Gong, J., Xiang, L., & Cao, Y. (2025). A Distributed Data Management and Service Framework for Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Observations. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244009