A Review of Cross-Modal Image–Text Retrieval in Remote Sensing

Highlights

- Identifies a convergence trend between real-valued representation and deep hashing methods in remote sensing (RS) cross-modal retrieval, propelled by large-scale vision-language pre-training (VLP) models to achieve finer-grained semantic alignment.

- Systematically synthesizes three key challenges—multi-scale semantic modeling, small object feature extraction, and multi-temporal feature understanding—that impede the effective application of cross-modal retrieval in remote sensing.

- Provides a clear technical framework tracing the evolution from global feature matching to fine-grained alignment mechanisms, serving as a foundational reference for guiding future research directions.

- Outlines prospective solutions and emerging trends, including self-supervised learning and neural architecture search, to overcome the unique challenges in RS cross-modal retrieval.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Multi-scale semantic modeling. How to construct a unified semantic representation that remains robust to scale variations in ground objects.

- (2)

- Small object feature extraction. How to effectively enhance the discriminability of small object features within complex backgrounds.

- (3)

- Multi-temporal feature understanding. How to model spatio-temporal dynamic semantics in image sequences and accurately align them with natural language descriptions.

2. Feature Representation Method

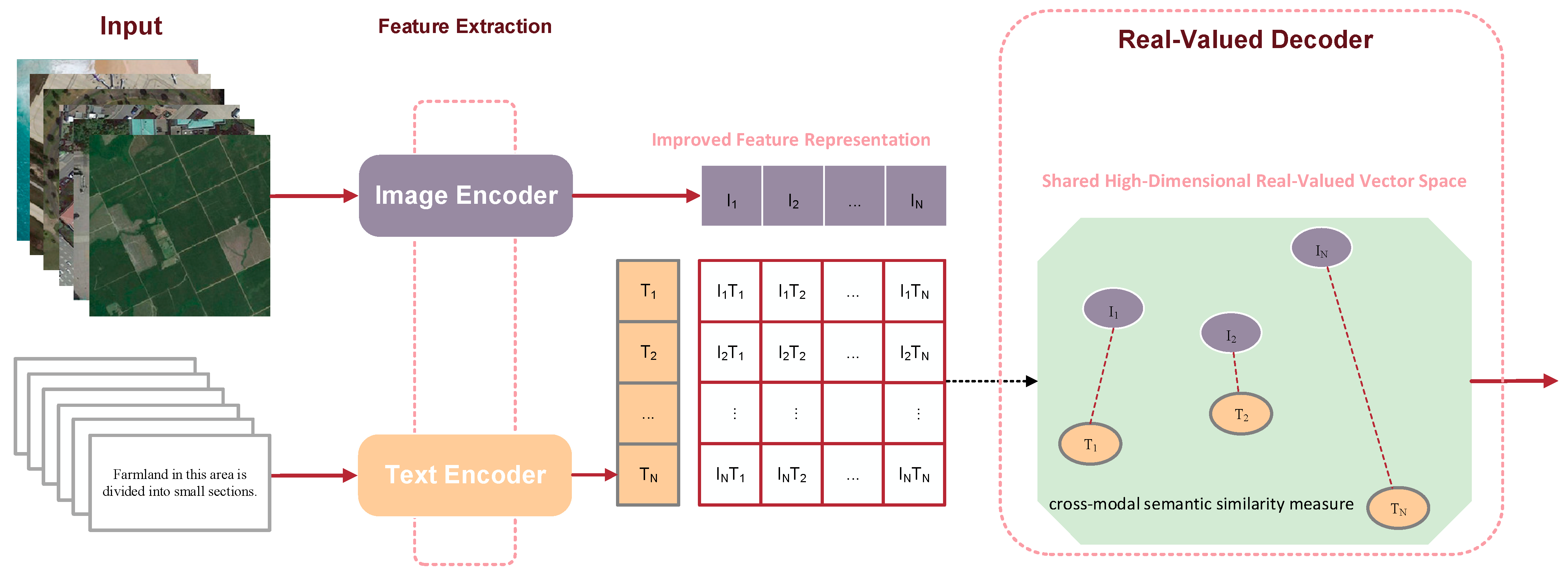

2.1. Real-Valued Representation in RS

- (1)

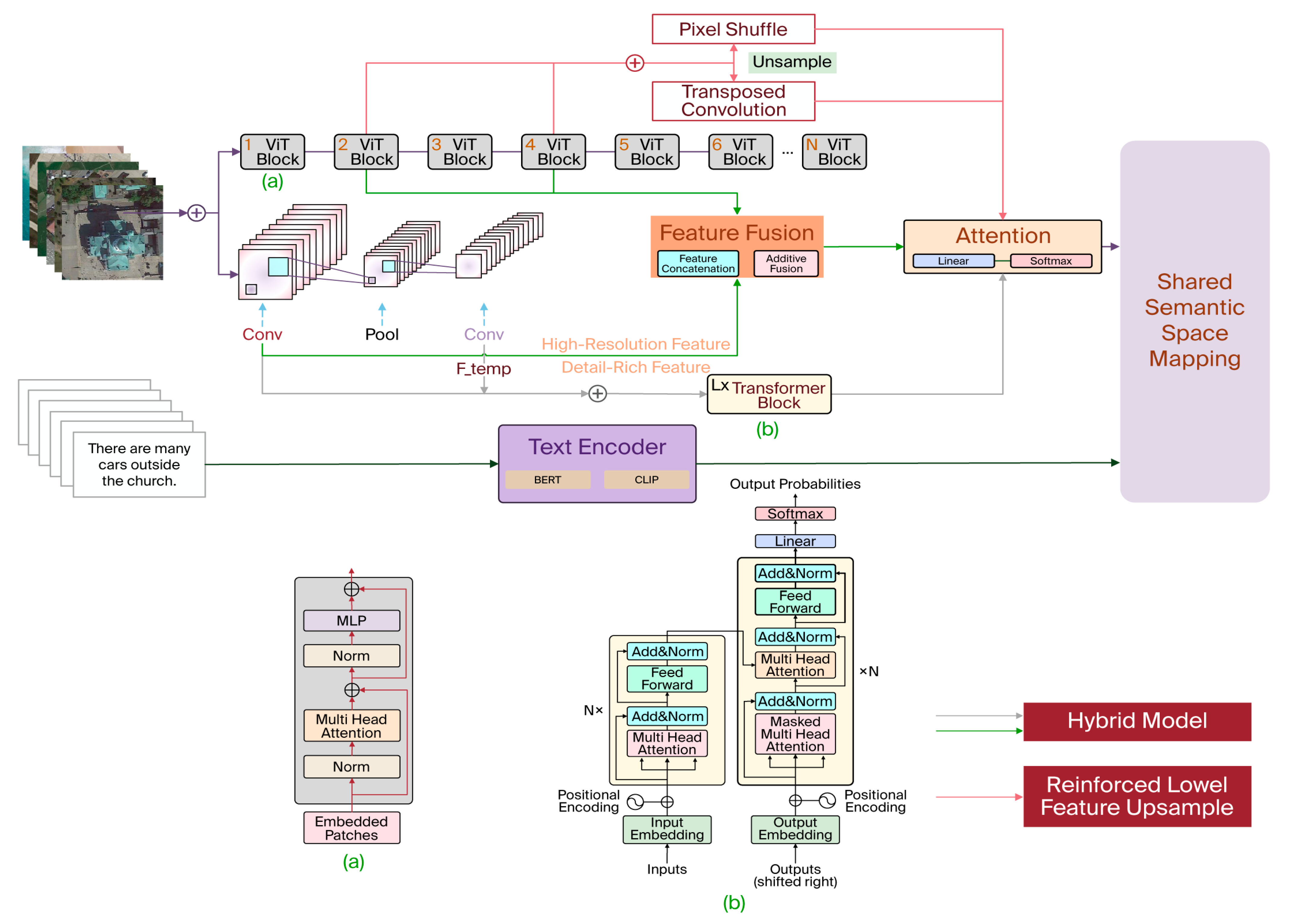

- Feature Extraction: An image encoder (e.g., CNN or ViT) processes an image to extract a visual feature vector . Concurrently, a text encoder (e.g., LSTM or BERT) processes a sentence to produce a textual feature vector

- (2)

- Projection to Shared Space: The visual and textual features are then projected into a common -dimensional semantic space using projection matrices. Respectively, the corresponding projection operations for visual and textual features are defined by Equations (1) and (2):where are learnable weight matrices, and are bias terms. The outputs are the final image and text embeddings.

- (3)

- Semantic Alignment via Loss Function: The key to modal alignment is the training objective. The triplet loss is a widely used mechanism for this purpose. Hence, it will be employed as an example to illustrate the alignment mechanism. For a given “anchor” sample—an image , with a “positive” sample and its matching text , and a “negative” sample and its a non-matching text —the loss function encourages the distance between the anchor and positive to be smaller than the distance between the anchor and negative by a margin . To formalize this objective, the triplet loss is defined as follows in Equation (3):where is a distance metric, such as cosine distance, and is a margin hyperparameter. The hinge loss function is defined separately in Equation (4) for clarity:This loss function directly minimizes the distance between matching pairs while pushing non-matching pairs apart, effectively achieving the alignment of image and text features in the shared space.

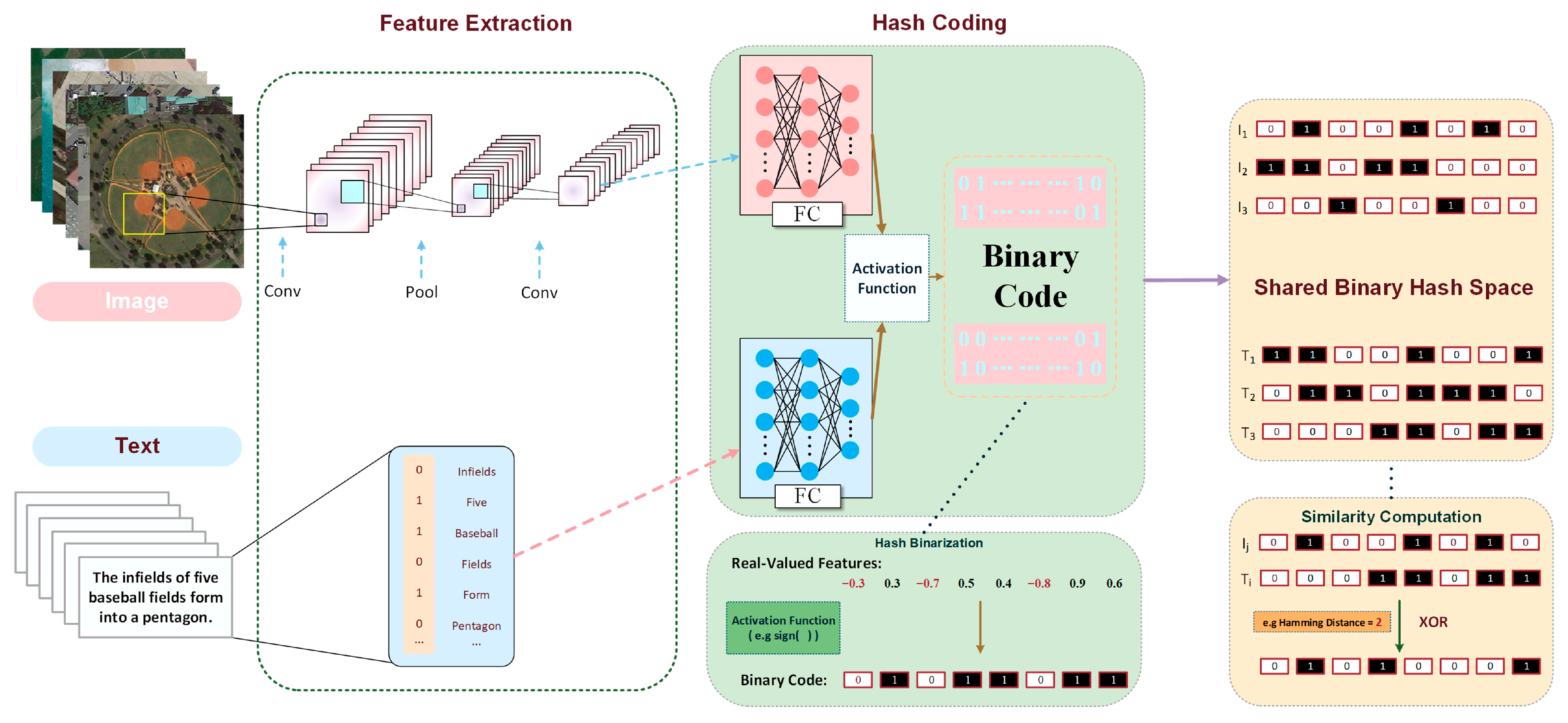

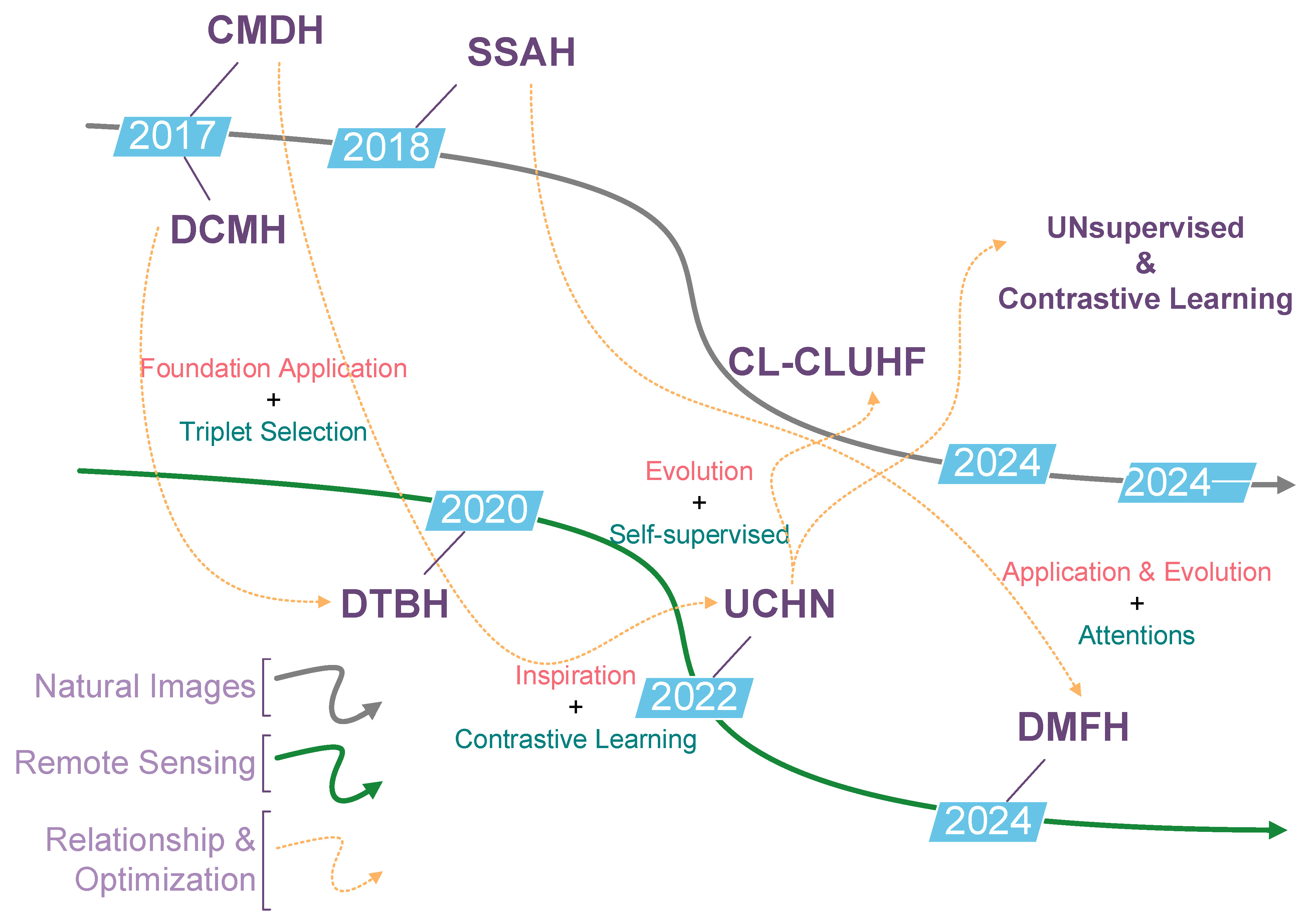

2.2. Deep Hashing in RS

- (1)

- Feature Extraction and Hashing Code Generation: Similarly to real-valued methods, image and text features are first extracted using dedicated encoders. Subsequently, a hashing layer, typically implemented as a fully connected layer with a -dimensional output, which is followed by a function used to generate the binary code. The corresponding binarization operations for visual and textual features are defined by Equations (5) and (6), respectively:where outputs if , else . However, the function has zero gradients almost everywhere, making direct backpropagation impossible. To circumvent this, a common practice during training is to use a continuous relaxation, such as the function, to generate continuous outputs , which are treated as approximate hash codes for the purpose of gradient computation.

- (2)

- Semantic Alignment via Similarity-Preserving Loss: The alignment objective is to ensure that the Hamming distance between hash codes reflects their semantic similarity. A supervised hashing loss often used is based on the inner product , which is linearly related to the Hamming distance. For a pair of image and text , let be their ground-truth similarity (e.g., if relevant, otherwise). The loss function encourages the inner product of the approximate codes of a relevant pair to be close to and that of an irrelevant pair to be close to . To formalize this objective, the similarity-preserving loss is defined as follows in Equation (7):

- (3)

- Quantization Loss: To mitigate the discrepancy between the continuous outputs and the discrete target binary codes , a quantization loss is added to force the continuous outputs to approach the discrete values. The quantization loss is defined separately in Equation (8):

2.3. Dominant Paradigm and Performance Comparison

3. Key Challenges

- (1)

- Modal Heterogeneity. Remote sensing images acquired by different sensors exhibit inherent differences in physical properties and scale characteristics, such as variations in ground object features and spatial resolution, which lead to diverse requirements for natural language expression.

- (2)

- Semantic Granularity Difference. Descriptions of natural image scenes typically operate at a relatively fixed scale, whereas RS text often needs to describe ground objects across multiple granularities.

- (3)

- Spatio-temporal Dynamics. RS images possess significant dynamic characteristics, and the extraction of change features differs considerably from that of static natural images.

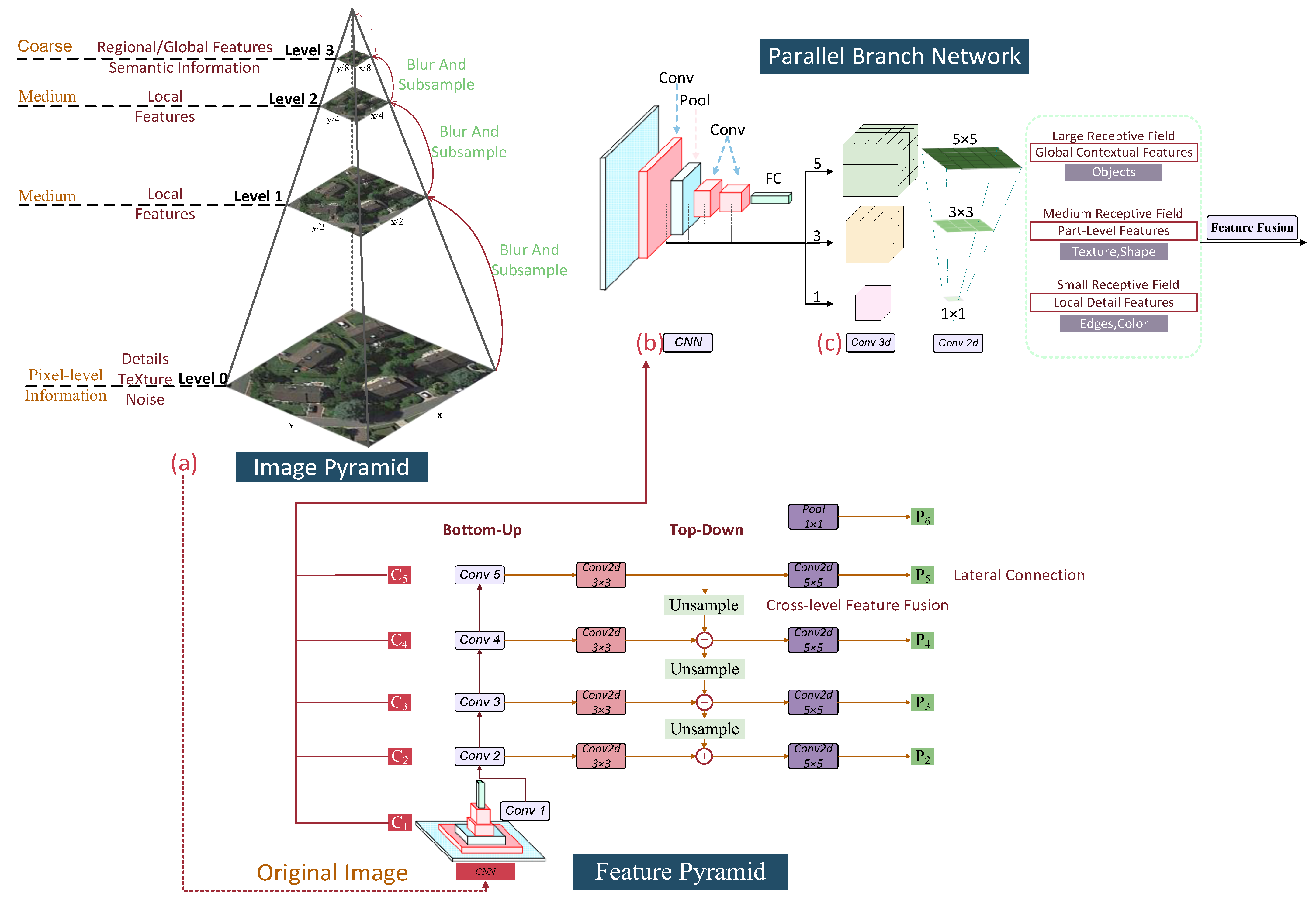

3.1. Multi-Scale

3.2. Small Objects

3.3. Multi-Temporal

4. Conclusions and Future Trends

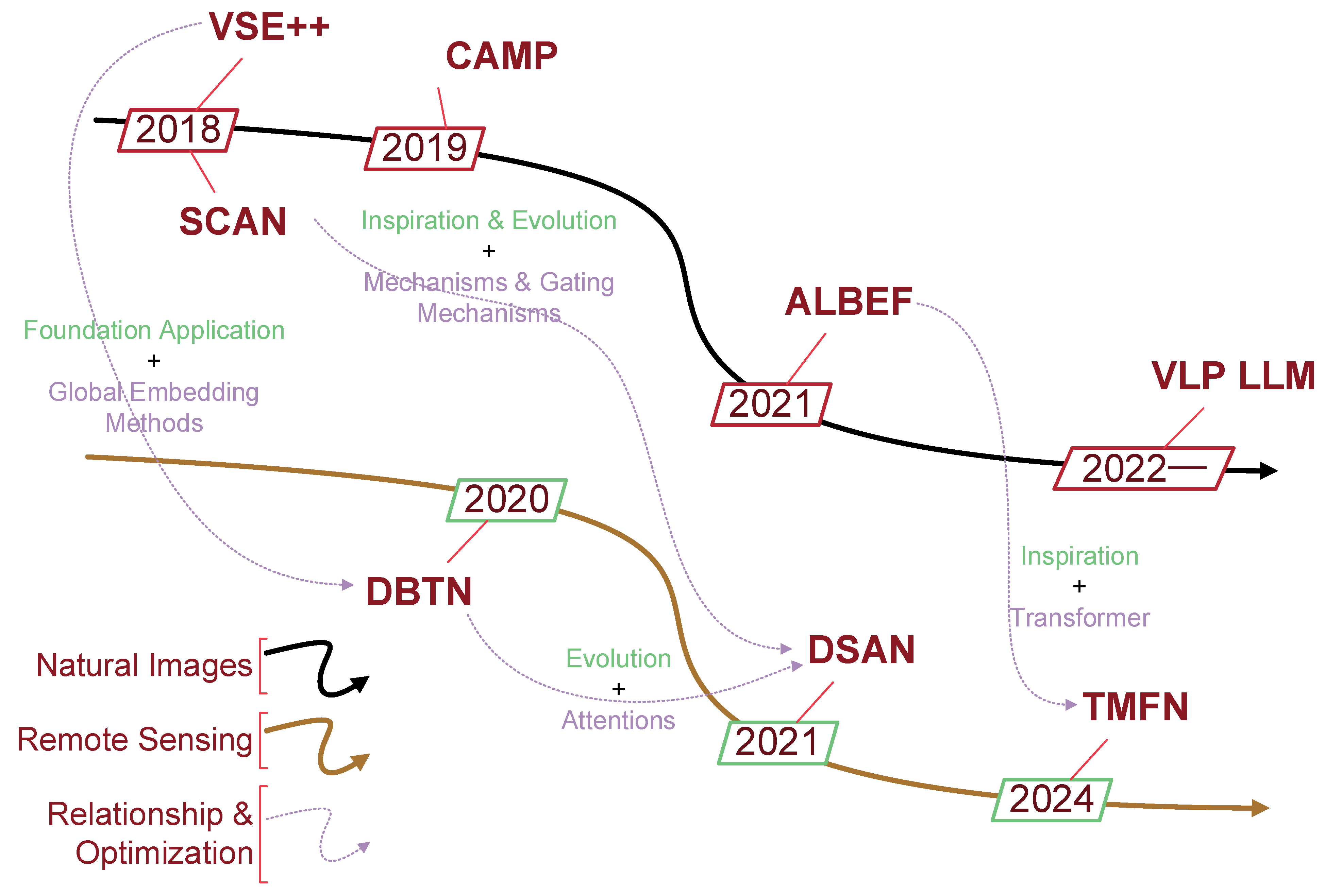

4.1. Overall Progress and Technological Evolution

4.2. Current Limitations and Open Problems

4.3. Future Research Directions

- (1)

- Richer and More Adaptive Semantic Representation. Integrating domain knowledge—such as geographic priors, sensor characteristics, and hierarchical land-cover semantics—into model architectures may enhance interpretability and alleviate annotation scarcity. The incorporation of neural architecture search (NAS) and adaptive feature selection may further balance performance and efficiency.

- (2)

- Unified Multi-Scale, Small Object, and Temporal Modeling Frameworks. Future retrieval systems should aim to jointly model large-scale spatial structures, fine-grained object details, and temporal change dynamics. This may be achieved by combining hierarchical feature pyramids, high-resolution refinement modules, and temporal reasoning blocks into an end-to-end cross-modal learning pipeline.

- (3)

- Next-Generation Datasets and Self-Supervised Learning. Building high-quality multi-temporal, multi-sensor, and fine-grained annotated datasets is crucial for capturing real-world complexity. In parallel, self-supervised, semi-supervised, and few-shot learning frameworks will reduce dependence on large-volume human annotations and improve cross-scene generalization.

- (4)

- Comprehensive Evaluation Systems for Real-World Deployment. Future benchmarks should incorporate multi-dimensional evaluation metrics covering retrieval accuracy, semantic consistency, robustness to atmospheric/sensor variations, interpretability, and computational efficiency. For multi-temporal understanding, hybrid metrics combining BLEU/ROUGE with change-detection accuracy will be essential.

4.4. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faghri, F.; Fleet, D.J.; Kiros, J.R.; Fidler, S. VSE++: Improving Visual-Semantic Embeddings with Hard Negatives. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1707.05612. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-H.; Chen, X.; Hua, G.; Hu, H.; He, X. Stacked Cross Attention for Image-Text Matching. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Sheng, L.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Shao, J. CAMP: Cross-Modal Adaptive Message Passing for Text-Image Retrieval. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5763–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Selvaraju, R.R.; Gotmare, A.D.; Joty, S.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. Align before Fuse: Vision and Language Representation Learning with Momentum Distillation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.07651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, T.; Bazi, Y.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Rangarajan, L.; Zuair, M. TextRS: Deep Bidirectional Triplet Network for Matching Text to Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L. A Deep Semantic Alignment Network for the Cross-Modal Image-Text Retrieval in Remote Sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 4284–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, P.; Ji, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, X. A Transformer-Based Multi-Modal Fusion Network for Semantic Segmentation of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 133, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, T.; Xu, C. Multi-Level Correlation Adversarial Hashing for Cross-Modal Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 22, 3101–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, V.E.; Lu, J.; Tan, Y.-P.; Zhou, J. Cross-Modal Deep Variational Hashing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4097–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.-Y.; Li, W.-J. Deep Cross-Modal Hashing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3270–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Deng, C.; Li, N.; Liu, W.; Gao, X.; Tao, D. Self-Supervised Adversarial Hashing Networks for Cross-Modal Retrieval. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.01223. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Luo, L.; Lai, H.; Yin, J. Category-Level Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Hashing in Cross-Modal Retrieval. Data Sci. Eng. 2024, 9, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, X. A Deep Hashing Technique for Remote Sensing Image-Sound Retrieval. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikriukov, G.; Ravanbakhsh, M.; Demir, B. Deep Unsupervised Contrastive Hashing for Large-Scale Cross-Modal Text-Image Retrieval in Remote Sensing. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.08125. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xiong, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiang, B. Deep Multiscale Fine-Grained Hashing for Remote Sensing Cross-Modal Retrieval. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6002205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, D.; Han, M.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Xu, S.; Xu, B. VLP: A Survey on Vision-Language Pre-Training. Mach. Intell. Res. 2023, 20, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Li, X.; Tao, D.; Lu, X. Deep Semantic Understanding of High Resolution Remote Sensing Image. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer, Information and Telecommunication Systems (CITS), Kunming, China, 6–8 July 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-Visual-Words and Spatial Extensions for Land-Use Classification. In Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 2–5 November 2010; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Li, X. Exploring Models and Data for Remote Sensing Image Caption Generation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Fu, K.; Li, X.; Deng, C.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. Exploring a Fine-Grained Multiscale Method for Cross-Modal Remote Sensing Image Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4404119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Guo, Y.; Yin, J. RS5M and GeoRSCLIP: A Large Scale Vision-Language Dataset and A Large Vision-Language Model for Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5642123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Prabha, R.; Huang, T.; Wu, J.; Rajagopal, R. SkyScript: A Large and Semantically Diverse Vision-Language Dataset for Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 5805–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Stewart, A.J.; Zhao, J.; Lehmann, N.; Dujardin, T.; Yuan, Z.; Ghamisi, P.; Zhu, X.X. GeoLangBind: Unifying Earth Observation with Agglomerative Vision-Language Foundation Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.06312. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Lu, X. Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: Benchmark and State of the Art. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Huang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Z. NWPU-Captions Dataset and MLCA-Net for Remote Sensing Image Captioning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5629419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, C.; Lu, X.; Li, X. RSGPT: A Remote Sensing Vision Language Model and Benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 224, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Mao, X. EarthGPT: A Universal Multimodal Large Language Model for Multisensor Image Comprehension in Remote Sensing Domain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5917820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Hanjalic, A.; Shen, H.T.; Song, J. Matching Images and Text with Multi-Modal Tensor Fusion and Re-Ranking. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1908.04011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Rong, X.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Fu, K.; Sun, X. A Lightweight Multi-Scale Crossmodal Text-Image Retrieval Method in Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5612819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Tian, C.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wang, H.; Fu, K.; Sun, X. MCRN: A Multi-Source Cross-Modal Retrieval Network for Remote Sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Pan, Z.; Mao, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. Learning to Evaluate Performance of Multimodal Semantic Localization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5631918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ma, Q.; Bai, C. Reducing Semantic Confusion: Scene-Aware Aggregation Network for Remote Sensing Cross-Modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Thessaloniki Greece, 12–15 June 2023; pp. 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. A Fine-Grained Semantic Alignment Method Specific to Aggregate Multi-Scale Information for Cross-Modal Remote Sensing Image Retrieval. Sensors 2023, 23, 8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Ma, Q.; Bai, C. A Prior Instruction Representation Framework for Remote Sensing Image-Text Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, X.; Sun, X. Hypersphere-Based Remote Sensing Cross-Modal Text–Image Retrieval via Curriculum Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5621815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Meng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, Y.; Li, X. Knowledge-Aided Momentum Contrastive Learning for Remote-Sensing Image Text Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5625213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, D.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Ye, Q.; Fu, L.; Zhou, J. RemoteCLIP: A Vision Language Foundation Model for Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5622216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Meng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Pang, Y.; Han, J. Eliminate Before Align: A Remote Sensing Image-Text Retrieval Framework with Keyword Explicit Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 1662–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Stewart, A.J.; Hanna, J.; Borth, D.; Papoutsis, I.; Saux, B.L.; Camps-Valls, G.; Zhu, X.X. Neural Plasticity-Inspired Multimodal Foundation Model for Earth Observation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2403.15356. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Stewart, A.J.; Zhao, J.; Lehmann, N.; Dujardin, T.; Yuan, Z.; Ghamisi, P.; Zhu, X.X. DOFA-CLIP: Multimodal Vision-Language Foundation Models for Earth Observation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.06312. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Meng, C.; Pang, Y.; Han, J. iEBAKER: Improved Remote Sensing Image-Text Retrieval Framework via Eliminate Before Align and Keyword Explicit Reasoning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.05644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Song, X.; Liu, G. Deeper and Mixed Supervision for Salient Object Detection in Automated Surface Inspection. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3751053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Miao, Q. (Eds.) Computer Vision: CCF Chinese Conference, CCCV 2015, Xi’an, China, September 18–20, 2015, Proceedings, Part II; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 547, ISBN 978-3-662-48569-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of Oriented Gradients for Human Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 1, pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qin, H.; Yan, J.; Li, X.; Hu, X. Scale-Aware Face Detection. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.09876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomè, D.; Monti, F.; Baroffio, L.; Bondi, L.; Tagliasacchi, M.; Tubaro, S. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Pedestrian Detection. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2016, 47, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Davis, L.S. An Analysis of Scale Invariance in Object Detection—SNIP. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1711.08189. [Google Scholar]

- Dollar, P.; Wojek, C.; Schiele, B.; Perona, P. Pedestrian Detection: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.4729. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Kook, H.-K.; Sun, J.-Y.; Kang, M.-C.; Ko, S.-J. Parallel Feature Pyramid Network for Object Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11209, pp. 239–256. ISBN 978-3-030-01227-4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.-X. Scale-Aware Trident Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6053–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermanet, P.; LeCun, Y. Traffic Sign Recognition with Multi-Scale Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, San Jose, CA, USA, 31 July–5 August 2011; pp. 2809–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Sun, F.; Huang, W.; Liu, H. Deep Feature Pyramid Reconfiguration for Object Detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.07993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Chen, K.; Shi, J.; Feng, H.; Ouyang, W.; Lin, D. Libra R-CNN: Towards Balanced Learning for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10778–10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.-Y.; Le, Q.V. NAS-FPN: Learning Scalable Feature Pyramid Architecture for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 13–19 June 2019; pp. 7029–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahhal, M.M.A.; Bazi, Y.; Abdullah, T.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Zuair, M. Deep Unsupervised Embedding for Remote Sensing Image Retrieval Using Textual Cues. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. A Fusion Encoder with Multi-Task Guidance for Cross-Modal Text–Image Retrieval in Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Cao, S.; Pu, T.; Peng, Z. Attention-Guided Pyramid Context Networks for Detecting Infrared Small Target Under Complex Background. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 4250–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Dense Nested Attention Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Wang, W.; Tan, S. IRSTFormer: A Hierarchical Vision Transformer for Infrared Small Target Detection. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Z.; Yao, L. CourtNet: Dynamically Balance the Precision and Recall Rates in Infrared Small Target Detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 233, 120996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Du, S.; Liu, C.; Cao, Z. Interior Attention-Aware Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5002013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, Z.; Xie, X.; Li, W. IST-TransNet: Infrared Small Target Detection Based on Transformer Network. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2023, 132, 104723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, S.; An, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Tao, J. An End-to-End Framework Based on Vision-Language Fusion for Remote Sensing Cross-Modal Text-Image Retrieval. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Chang, H.; Sun, H. High-Resolution Network with Transformer Embedding Parallel Detection for Small Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikouei, M.; Baroutian, B.; Nabavi, S.; Taraghi, F.; Aghaei, A.; Sajedi, A.; Moghaddam, M.E. Small Object Detection: A Comprehensive Survey on Challenges, Techniques and Real-World Applications. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 27, 200561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. RSRefSeg: Referring Remote Sensing Image Segmentation with Foundation Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xu, T.; Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Li, J. A Lightweight Fusion Strategy with Enhanced Interlayer Feature Correlation for Small Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4708011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Mu, T.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Ke, W.; Yang, Q.; He, Z. PBT: Progressive Background-Aware Transformer for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5004513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, M.; Luo, J.; Pu, H.; Feng, Y.; Wei, X.; Jia, W. Boundary-Aware Feature Fusion with Dual-Stream Attention for Remote Sensing Small Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5600213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Liu, B.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Q. MwdpNet: Towards Improving the Recognition Accuracy of Tiny Targets in High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; You, S.; Hu, X.; Yang, P.; Zhao, J. SEB-YOLO: An Improved YOLOv5 Model for Remote Sensing Small Target Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Su, L.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, T. YOLO-DHGC: Small Object Detection Using Two-Stream Structure with Dense Connections. Sensors 2024, 24, 6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.-J. BLEU: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics—ACL ’02, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–12 July 2002; Association for Computational Linguistics: St, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2001; p. 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y. ROUGE: A Package for Automatic Evaluation of Summaries; Association for Computational Linguistics: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Cheng, M.-M.; He, R.; Ubul, K.; Silamu, W.; Zha, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.-L. (Eds.) Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision: 7th Chinese Conference, PRCV 2024, Urumqi, China, October 18–20, 2024, Proceedings, Part V; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 15035, ISBN 978-981-97-8619-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Tong, Z.; Ji, B.; Wu, G. TDN: Temporal Difference Networks for Efficient Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Kang, B.-H. (Eds.) PRICAI 2018: Trends in Artificial Intelligence: 15th Pacific Rim International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Nanjing, China, August 28–31, 2018, Proceedings, Part I; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11012, ISBN 978-3-319-97303-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.; Gao, Z.; Wu, L.; Xu, Y.; Xia, J.; Li, S.; Li, S.Z. Temporal Attention Unit: Towards Efficient Spatiotemporal Predictive Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 18770–18782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, C.-L.; Zhao, C.; Ghanem, B. End-to-End Temporal Action Detection with 1B Parameters Across 1000 Frames. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 18591–18601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Xu, F.; Chen, X.; Dong, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, J. The ClearSCD Model: Comprehensively Leveraging Semantics and Change Relationships for Semantic Change Detection in High Spatial Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 211, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Ji, S.; Guo, H.; Yu, A. Learning SAR-Optical Cross Modal Features for Land Cover Classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Dudhane, A.; Debary, H.; Fiaz, M.; Munir, M.A.; Danish, M.S.; Fraccaro, P.; Watson, C.D.; Klein, L.J.; Khan, F.S.; et al. EarthDial: Turning Multi-Sensory Earth Observations to Interactive Dialogues. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Mou, L.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, X.X. Change Detection Meets Visual Question Answering. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5630613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Pu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wan, Q. Remote Sensing Image Change Captioning Using Multi-Attentive Network with Diffusion Model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Number of Images | Image Size | Captioning Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sydney-Caption [18] | 613 | 500 × 500 | 5 sentences per image |

| UCM-Caption [18,19] | 2100 | 256 × 256 | 5 sentences per image |

| RSICD [20] | 10,921 | 224 × 224 | 1–5 sentences per image |

| RSITMD [21] | 4743 | 256 × 256 | 5 sentences per image + Fine-grained keywords |

| NWPU-Caption [25,26] | 31,500 | 256 × 256 | 5 sentences per image |

| RSICap [27] | 2585 | 512 × 512 | 1 high-quality human-annotated caption per image |

| RS5M [22] | 5 million | All Resolutions | Keyword filtering + BLIP-2 generation |

| SkyScript [23] | 5.2 million+ | All Resolutions | Automated generation + CLIP filtering |

| MMRS-1Msubset [28] | 1 million+ | All Resolutions | Multi-task instruction following |

| GeoLangBind-2Msubset [24] | 2 million+ | All Resolutions | Dataset integration + Automated generation |

| Method | Year | Backbone | Image-to-Text Retrieval | Text-to-Image Retrieval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision Encoding/ Text Encoding | RSICD Dataset | RSITMD Dataset | RSICD Dataset | RSITMD Dataset | ||

| mR = (R@1 + R@5 + R@10)/3 | mR = (R@1 + R@5 + R@10)/3 | |||||

| VSE++BMVC [1] | 2018 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 10.12 | 25.88 | 10.75 | 23.78 |

| SCANECCV [2] | 2018 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 12.86 | 25.44 | 15.61 | 27.11 |

| CAMP-tripletICCV [3] | 2019 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 13.04 | 25.59 | 15.73 | 26.80 |

| MTFNACM [29] | 2019 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 12.43 | 24.78 | 17.19 | 29.06 |

| LW-MCR-dTGRS [30] | 2022 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 11.91 | 26.33 | 17.40 | 29.25 |

| AMFMNTGRS [21,30] | 2022 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 14.62 | 25.74 | 18.21 | 33.69 |

| SWANACM [33] | 2023 | ResNet/Glove + Bi-GRU | 19.47 | 30.80 | 21.74 | 37.41 |

| HVSATGRS [36] | 2023 | ResNet18/Bi-GRU | 20.07 | 30.29 | 20.26 | 36.03 |

| FAAMISensors [34] | 2023 | DetNet/BERT | 21.33 | 33.55 | 25.02 | 38.44 |

| PIRACM [35] | 2023 | Swin-T + ResNet/BERT | 25.43 | 37.39 | 23.48 | 39.09 |

| KAMCLTGRS [37] | 2023 | ResNet/Bi-GRU | 26.01 | 33.97 | 26.20 | 38.32 |

| RemoteCLIPTGRS [38] | 2024 | ResNet + ViT/CLIP | 35.50 | 48.08 | 35.02 | 50.68 |

| GeoRSCLIPTGRS [22] | 2024 | ViT/CLIP | 39.49 | 51.18 | 38.26 | 52.43 |

| EBAKERACM [39] | 2024 | ViT/CLIP | 41.75 | 52.07 | 39.64 | 54.57 |

| SkyCLIPAAAI [23] | 2024 | ViT/CLIP | 23.70 | 30.75 | 19.97 | 30.58 |

| iEBAKERESWA [42] | 2025 | ViT/CLIP | 46.72 | 55.46 | 43.41 | 55.65 |

| GeoLangBind-LarXiv [24] | 2025 | ViT/CLIP | 23.54 | 29.57 | 23.59 | 35.98 |

| Method | Metric | Dataset | Baseline Methods | Accuracy Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSRefSeg [73] | cIoU | RRSIS-D | RMISN | +0.74 |

| FIANet | +0.33 | |||

| gIoU | RMISN | +2.4 | ||

| FIANet | +0.66 | |||

| EFC [74] | mAP | VisDrone | GFL | +0.017 |

| COCO | RetinaNet | +0.011 | ||

| GFL | +0.01 | |||

| PBT [75] | loU | NUDT-SIRST | UIU-Net | +1.38 |

| IRSTD-1k | +1.76 | |||

| IRSTD-Air | +0.71 | |||

| BAFNet [76] | AP | AI-TOD | CAF2ENet-S | +2.4 |

| VisDrone | CMDNet | +1.6 | ||

| MwdpNet [77] | mAP | Dataset 1 | MDSSD | +0.007 |

| Dataset 2 | YOLOV6-M | -0.004 | ||

| Dataset 3 | R-FCN | +0.012 | ||

| SEB-YOLO [78] | mAP | NWPU VHR-10 | Original YOLOv5 | +0.04 |

| RSOD | +0.053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Ha, D.; Zhang, H. A Review of Cross-Modal Image–Text Retrieval in Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3995. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243995

Xu L, Wang L, Zhang J, Ha D, Zhang H. A Review of Cross-Modal Image–Text Retrieval in Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3995. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243995

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Lingxin, Luyao Wang, Jinzhi Zhang, Da Ha, and Haisu Zhang. 2025. "A Review of Cross-Modal Image–Text Retrieval in Remote Sensing" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3995. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243995

APA StyleXu, L., Wang, L., Zhang, J., Ha, D., & Zhang, H. (2025). A Review of Cross-Modal Image–Text Retrieval in Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3995. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243995