Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S. and G.H.; methodology, X.S.; software, X.S.; validation, X.S. and G.H.; formal analysis, X.S.; investigation, X.S.; resources, G.H.; data curation, X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.S.; writing—review and editing, G.H.; visualization, X.S.; supervision, G.H.; project administration, G.H.; funding acquisition, G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Distribution of ancient walled city sites in the Qinghai Lake Basin. Numbers indicate the locations of major known sites: (1) Yangchang South Ancient City; (2) Yangchang North Ancient City; (3) Hargai Ancient City; (4) Beixiangyang Ancient City; (5) Nanxiangyang Ancient City; (6) Cangkai Ancient City; (7) Xihai Commandery City; (8) Gahai Ancient City; (9) Fusi City; (10) Upper Jiala Ancient City; (11) Lower Jiala Ancient City; (12) Shangtama Ancient City; (13) Shangtama–Xiazhatan Ancient City; (14) Zhengdongba Ancient City; (15) North Zhujianliang Site of Dongba Ancient City; (16) Dongtai Western Han Lankasuo City (Dongba Township); (17) Xitai Gorge-edge Ancient City; (18) Xinsi Back Terrace Ancient City; (19) Shangmeitai Ancient City; (20) Xitai Ancient City (Dongba Brigade); (21) Kecai Ancient City; (22) Zhihai Ancient City; (23) Daoganri Ancient City; (24) Qunke Jiala Ancient City; (25) Western Extension of Qunke Jiala; (26) Eastern Extension of Qunke Jiala; (27) Southeastern Extension of Qunke Jiala; (28) Eastern Architectural Site of Qunke Jiala; (29) Hei (Black) Ancient City; (30) Nahailie Ancient City; (31) General’s Temple Ancient City; (32) Hudong Yangchang Ancient City; (33) Dacang Jianggai Ancient City; (34) Haixinshan Ancient City (Yinglong City); (35) Jinquan Ancient City; (36) Dalai Mani Ancient City No. 1; (37) Dalai Mani Ancient City No. 2.

Figure 1.

Distribution of ancient walled city sites in the Qinghai Lake Basin. Numbers indicate the locations of major known sites: (1) Yangchang South Ancient City; (2) Yangchang North Ancient City; (3) Hargai Ancient City; (4) Beixiangyang Ancient City; (5) Nanxiangyang Ancient City; (6) Cangkai Ancient City; (7) Xihai Commandery City; (8) Gahai Ancient City; (9) Fusi City; (10) Upper Jiala Ancient City; (11) Lower Jiala Ancient City; (12) Shangtama Ancient City; (13) Shangtama–Xiazhatan Ancient City; (14) Zhengdongba Ancient City; (15) North Zhujianliang Site of Dongba Ancient City; (16) Dongtai Western Han Lankasuo City (Dongba Township); (17) Xitai Gorge-edge Ancient City; (18) Xinsi Back Terrace Ancient City; (19) Shangmeitai Ancient City; (20) Xitai Ancient City (Dongba Brigade); (21) Kecai Ancient City; (22) Zhihai Ancient City; (23) Daoganri Ancient City; (24) Qunke Jiala Ancient City; (25) Western Extension of Qunke Jiala; (26) Eastern Extension of Qunke Jiala; (27) Southeastern Extension of Qunke Jiala; (28) Eastern Architectural Site of Qunke Jiala; (29) Hei (Black) Ancient City; (30) Nahailie Ancient City; (31) General’s Temple Ancient City; (32) Hudong Yangchang Ancient City; (33) Dacang Jianggai Ancient City; (34) Haixinshan Ancient City (Yinglong City); (35) Jinquan Ancient City; (36) Dalai Mani Ancient City No. 1; (37) Dalai Mani Ancient City No. 2.

![Remotesensing 17 03997 g001 Remotesensing 17 03997 g001]()

Figure 2.

Examples of positive and negative samples in the Qinghai Lake Ancient City Dataset (QHACD). (a–d) represent positive samples of confirmed ancient city sites: (a) Dachang Jianggai Ancient City, (b) Gala Upper Ancient City, (c) Xihai Jun Ancient City, and (d) Fusi City. (e–h) represent negative samples collected from non-archaeological areas with similar morphological or spectral characteristics, including (e) salt-lake textures, (f) agricultural grids, (g) modern industrial facilities, and (h) contemporary settlements. All samples are derived from 0.8 m GF-2 pan-sharpened imagery and annotated as part of the QHACD to enhance model discrimination between archaeological and modern anthropogenic features. Green bounding boxes indicate confirmed ancient-city targets, while purple bounding boxes denote negative samples.

Figure 2.

Examples of positive and negative samples in the Qinghai Lake Ancient City Dataset (QHACD). (a–d) represent positive samples of confirmed ancient city sites: (a) Dachang Jianggai Ancient City, (b) Gala Upper Ancient City, (c) Xihai Jun Ancient City, and (d) Fusi City. (e–h) represent negative samples collected from non-archaeological areas with similar morphological or spectral characteristics, including (e) salt-lake textures, (f) agricultural grids, (g) modern industrial facilities, and (h) contemporary settlements. All samples are derived from 0.8 m GF-2 pan-sharpened imagery and annotated as part of the QHACD to enhance model discrimination between archaeological and modern anthropogenic features. Green bounding boxes indicate confirmed ancient-city targets, while purple bounding boxes denote negative samples.

Figure 3.

Illustration of data augmentation strategies for the Qinghai Lake Ancient City Dataset (QHACD). Panels are shown in the same order as the code outputs: (a–e) five examples of geometric/radiometric augmentations on the same tile (random rotation/flip, scale–shift–rotate, random crop, and brightness/contrast/saturation jitter, ±20%); (f) Mosaic augmentation formed by randomly combining four tiles from the study area; (g) MixUp augmentation obtained by linear blending of two independently augmented tiles; (h) the original GF-2 pan-sharpened image (0.8 m). All tiles are 450 m × 450 m (562 × 562 px). These augmentations increase sample diversity and improve model generalization.

Figure 3.

Illustration of data augmentation strategies for the Qinghai Lake Ancient City Dataset (QHACD). Panels are shown in the same order as the code outputs: (a–e) five examples of geometric/radiometric augmentations on the same tile (random rotation/flip, scale–shift–rotate, random crop, and brightness/contrast/saturation jitter, ±20%); (f) Mosaic augmentation formed by randomly combining four tiles from the study area; (g) MixUp augmentation obtained by linear blending of two independently augmented tiles; (h) the original GF-2 pan-sharpened image (0.8 m). All tiles are 450 m × 450 m (562 × 562 px). These augmentations increase sample diversity and improve model generalization.

Figure 4.

Simplified structure of the Dual-Path Excitation Block (DPEB) in AC-SENet. The module receives an input feature map , performs global average pooling, and processes it through two fully connected layers (FC1, FC2) with ReLU and Sigmoid activations to generate a channel attention weight vector. This vector recalibrates feature responses, enhancing salient structural details such as city walls and corners while suppressing background noise. Different colors represent different functional components of the DPEB, including channel attention, spatial attention, and feature fusion paths.

Figure 4.

Simplified structure of the Dual-Path Excitation Block (DPEB) in AC-SENet. The module receives an input feature map , performs global average pooling, and processes it through two fully connected layers (FC1, FC2) with ReLU and Sigmoid activations to generate a channel attention weight vector. This vector recalibrates feature responses, enhancing salient structural details such as city walls and corners while suppressing background noise. Different colors represent different functional components of the DPEB, including channel attention, spatial attention, and feature fusion paths.

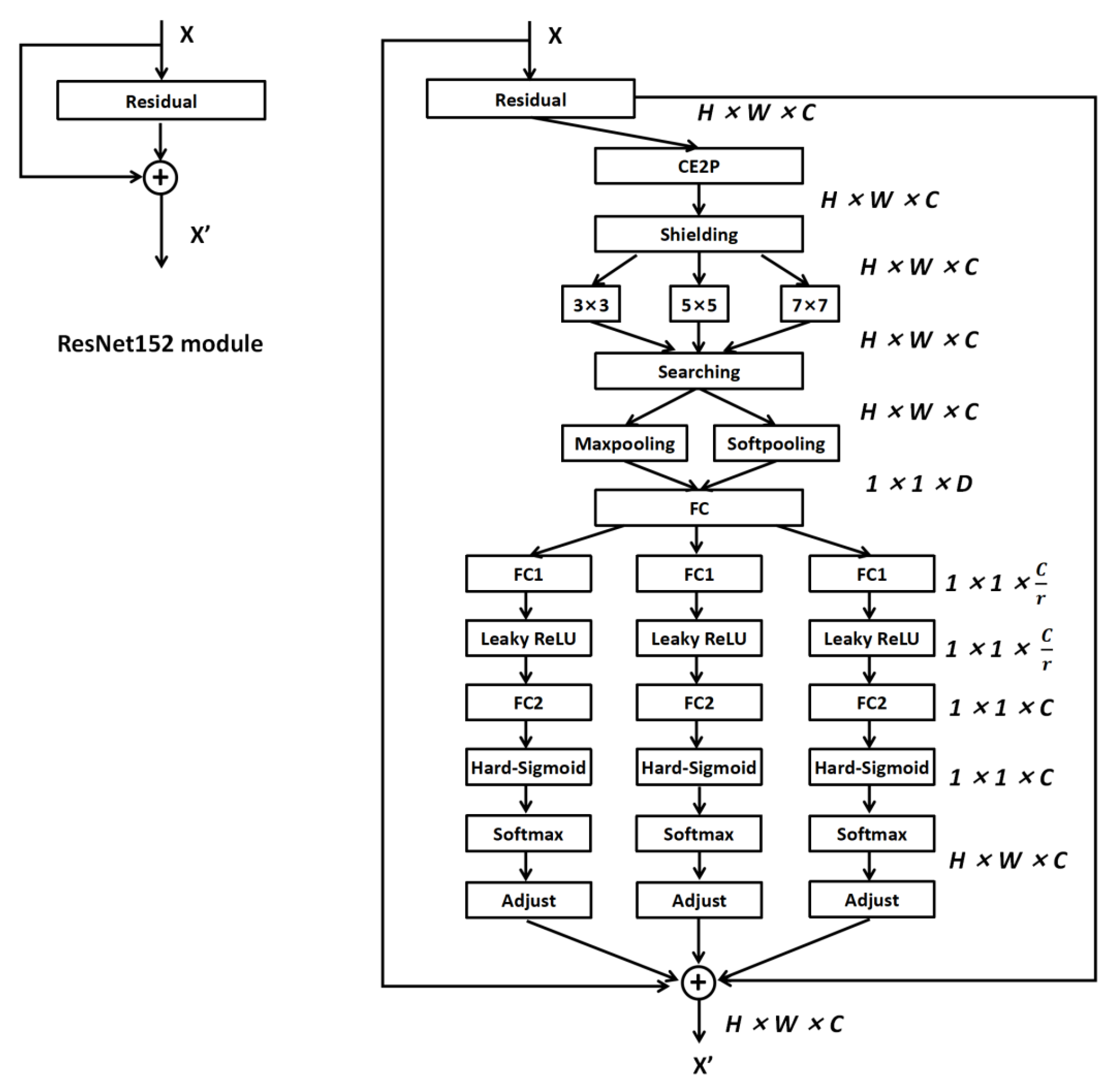

Figure 5.

Structure of the adjustment module in AC-SENet (based on a ResNet-152 residual block). The module fuses three scale-specific feature maps through 1 × 1 convolution and Softmax normalization to generate dynamic weights The fused feature is then refined by a deformable convolution with learnable offsets and merged with the residual input . This process enhances robustness to erosion-induced boundary degradation and irregular city-wall geometries in GF-2 imagery.

Figure 5.

Structure of the adjustment module in AC-SENet (based on a ResNet-152 residual block). The module fuses three scale-specific feature maps through 1 × 1 convolution and Softmax normalization to generate dynamic weights The fused feature is then refined by a deformable convolution with learnable offsets and merged with the residual input . This process enhances robustness to erosion-induced boundary degradation and irregular city-wall geometries in GF-2 imagery.

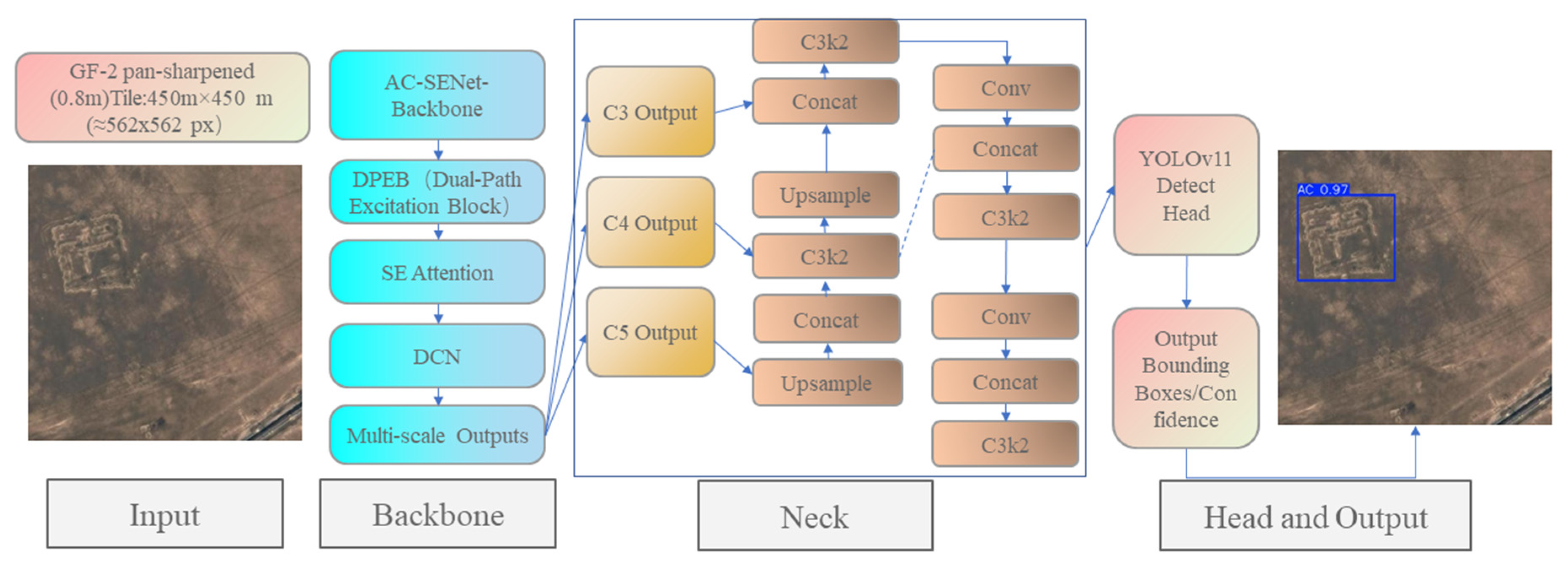

Figure 6.

Overall architecture of the AC-YOLOv11 model for ancient city detection. The AC-YOLOv11 model integrates the AC-SENet backbone (ResNet-152 with SE and dual-path attention modules) with the YOLOv11 neck and detection head. Multi-scale features (C3–C5) extracted from GF-2 pan-sharpened images are fused via PANet for ancient city identification.

Figure 6.

Overall architecture of the AC-YOLOv11 model for ancient city detection. The AC-YOLOv11 model integrates the AC-SENet backbone (ResNet-152 with SE and dual-path attention modules) with the YOLOv11 neck and detection head. Multi-scale features (C3–C5) extracted from GF-2 pan-sharpened images are fused via PANet for ancient city identification.

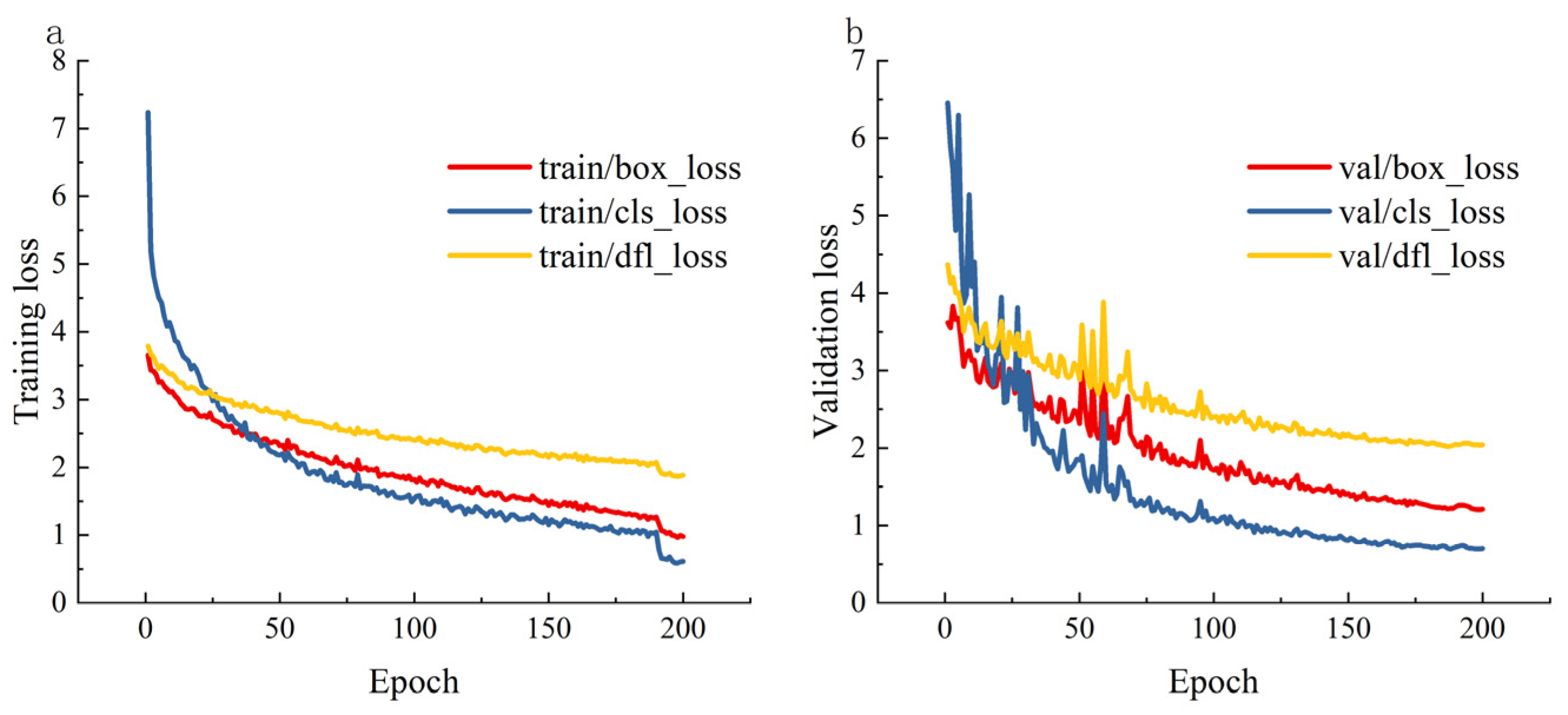

Figure 7.

Training and validation loss curves of AC-YOLOv11. (a) Training losses, including box_loss, cls_loss, and dfl_loss; (b) Validation losses, including val/box_loss, val/cls_loss, and val/dfl_loss.

Figure 7.

Training and validation loss curves of AC-YOLOv11. (a) Training losses, including box_loss, cls_loss, and dfl_loss; (b) Validation losses, including val/box_loss, val/cls_loss, and val/dfl_loss.

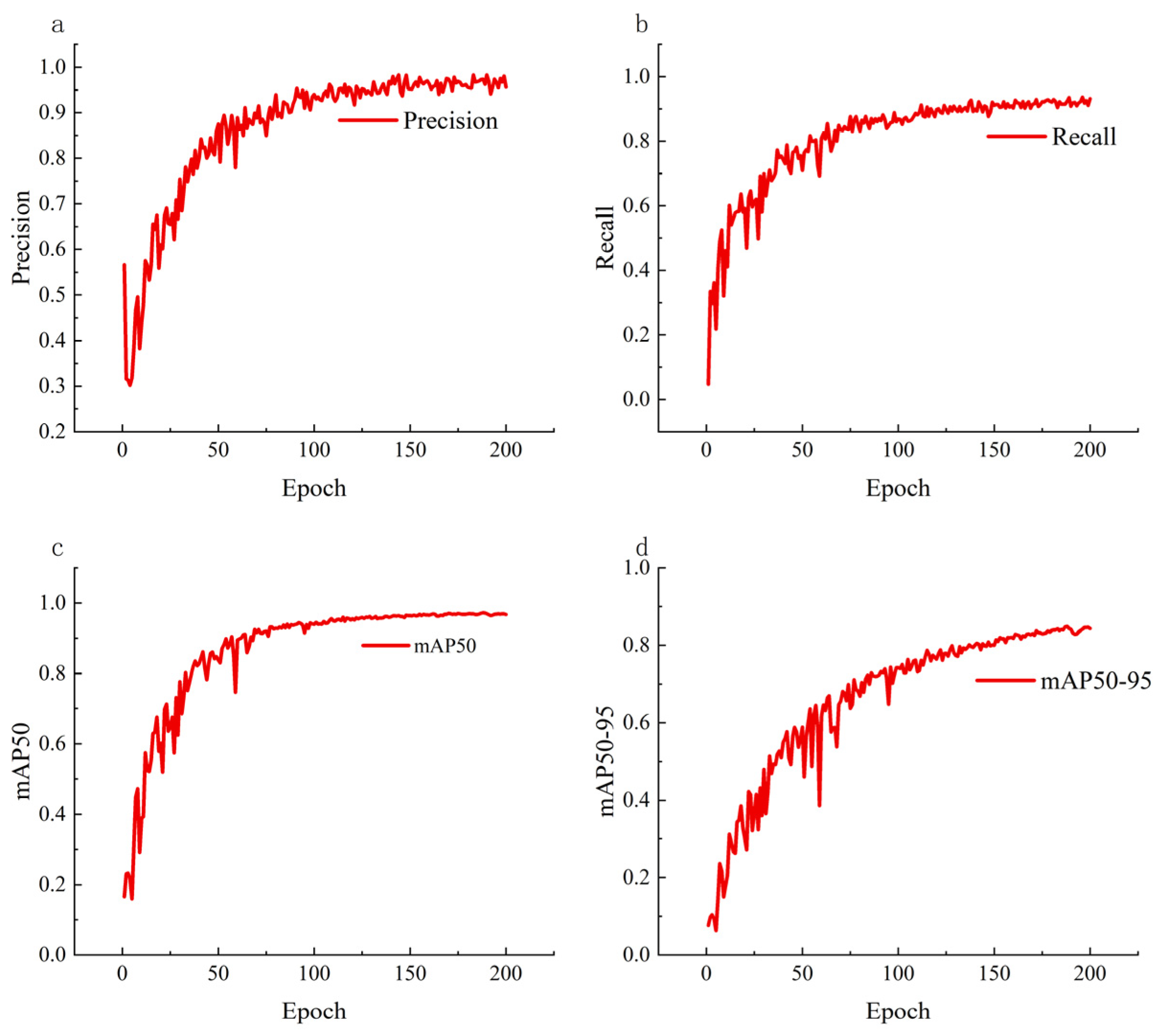

Figure 8.

Performance curves of AC-YOLOv11 across 200 training epochs. (a) Precision; (b) Recall; (c) mAP@0.5; (d) mAP@0.5:0.95.

Figure 8.

Performance curves of AC-YOLOv11 across 200 training epochs. (a) Precision; (b) Recall; (c) mAP@0.5; (d) mAP@0.5:0.95.

Figure 9.

F1-score variation across 200 epochs of training for AC-YOLOv11 on the QHACD.

Figure 9.

F1-score variation across 200 epochs of training for AC-YOLOv11 on the QHACD.

Figure 10.

Visualized detection results of ancient city sites in the QHACD validation set. Panels (a–p) show representative prediction examples randomly selected from the validation set. Blue bounding boxes indicate the detected ancient-city targets, and the numbers displayed beside the boxes represent the corresponding confidence scores predicted by the model.

Figure 10.

Visualized detection results of ancient city sites in the QHACD validation set. Panels (a–p) show representative prediction examples randomly selected from the validation set. Blue bounding boxes indicate the detected ancient-city targets, and the numbers displayed beside the boxes represent the corresponding confidence scores predicted by the model.

Figure 11.

Model detection examples of typical ancient city sites in the Qinghai Lake Basin. AC-YOLOv11 detection results under different geomorphic and surface conditions: (a) complete rectangular enclosure; (b) degraded rammed-earth remains; (c) vegetated area; (d) main city with subsidiary Wengcheng; (e) partially cropped ancient city; (f) heavily eroded zone; (g) modern disturbance area; (h) simple geomorphic unit. All detections were performed at a confidence threshold of 0.75 (blue bounding boxes), showing robust geometric and contour extraction capability.

Figure 11.

Model detection examples of typical ancient city sites in the Qinghai Lake Basin. AC-YOLOv11 detection results under different geomorphic and surface conditions: (a) complete rectangular enclosure; (b) degraded rammed-earth remains; (c) vegetated area; (d) main city with subsidiary Wengcheng; (e) partially cropped ancient city; (f) heavily eroded zone; (g) modern disturbance area; (h) simple geomorphic unit. All detections were performed at a confidence threshold of 0.75 (blue bounding boxes), showing robust geometric and contour extraction capability.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of 74 highly probable ancient city sites detected in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of 74 highly probable ancient city sites detected in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 13.

Spatial relationship between ancient city sites and river systems (10 km buffer) in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 13.

Spatial relationship between ancient city sites and river systems (10 km buffer) in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 14.

Altitudinal distribution of ancient city sites in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 14.

Altitudinal distribution of ancient city sites in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 15.

Spatial relationship between ancient city sites and slope gradients in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Figure 15.

Spatial relationship between ancient city sites and slope gradients in the Qinghai Lake Basin.

Table 1.

Parameter settings for AC-YOLOv11 training.

Table 1.

Parameter settings for AC-YOLOv11 training.

| Parameters | Setup |

|---|

| Epochs | 200 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Workers | 4 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Imgsz | 640 |

| Ratio of training set to validation set | 8:2 |

Table 2.

Evaluation metrics used for model performance assessment.

Table 2.

Evaluation metrics used for model performance assessment.

| Metric | Formula | Definition | Purpose |

|---|

| Loss function (L) | | Measures the error between predicted and ground-truth values across classes. In this single-class detection task, YOLO combines bounding box regression loss and distribution focal loss. | Evaluates training stability and effectiveness of learning rate scheduling. |

| Precision | | Proportion of correctly predicted positives among all predicted positives. | Reflects the accuracy of positive predictions. |

| Recall | | Proportion of actual positives correctly identified by the model. | Reflects the completeness of positive detection. |

| Mean Average Precision (mAP) | | The mean of AP values across all N classes. Since N = 1, equals AP for the “Ancient City” class. Includes (IoU = 0.5) and (averaged across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95). | Provides a comprehensive measure of detection precision and localization accuracy. |

| F1 Score | | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. | Provides a balanced evaluation when precision and recall are uneven. |

Table 3.

Ablation experiment results of AC-YOLOv11 on the QHACD.

Table 3.

Ablation experiment results of AC-YOLOv11 on the QHACD.

| ID | Model Variant | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Inference Speed (ms) |

|---|

| 1 | YOLOv11 (Original Backbone) | 88.6 | 83.1 | 85.7 | 78.5 | 70.4 | 5.1–5.3 |

| 2 | + ResNet-152 Backbone | 90.3 | 86.7 | 88.4 | 80.9 | 72.6 | 5.4–5.6 |

| 3 | + ResNet-152 + SE Attention | 94.5 | 89.2 | 91.7 | 81.8 | 73.4 | 5.7–5.9 |

| 4 | + ResNet-152 + DPEB (Ours) | 97.5 | 91.2 | 94.2 | 82.3 | 74.9 | 6.2 |

Table 4.

Comparison of detection performance among different models on the QHACD.

Table 4.

Comparison of detection performance among different models on the QHACD.

| Model | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Inference Speed (ms) |

|---|

| YOLOv3 | 89.1 | 84.3 | 86.6 | 78.9 | 70.5 | 7.8 |

| YOLOv4 | 91.5 | 86.9 | 89.1 | 81.2 | 72.4 | 8.5 |

| YOLOv7 | 92.3 | 88.1 | 90.1 | 82 | 73.5 | 5 |

| EfficientDet-D3 | 90.2 | 85.4 | 87.7 | 80.1 | 72 | 12 |

| AC-YOLOv11 (Ours) | 97.5 | 91.2 | 94.2 | 82.3 | 74.9 | 6.2 |

Table 5.

Field verification results of suspected ancient city sites detected by the AC-YOLOv11 model.

Table 5.

Field verification results of suspected ancient city sites detected by the AC-YOLOv11 model.

| ID | Coordinates (Lat, Long) | Distance to Known Site | Surface Remains | Surface Artifacts | Geomorphic Setting | Final Interpretation |

|---|

| 1 | 37°02′57.23″N, 99°31′47.39″E | ~5.2 km from Fusi City | Rammed-earth wall segments and low stone foundations; irregular plan | Painted porcelain sherds | Piedmont alluvial-fan terrace; gentle slope | Non-ancient city (modern disturbance) |

| 2 | 37°02′44.10″N, 99°32′15.70″E | ~4.4 km from Fusi City | Fragmented rammed-earth wall bases with fissures and voids | Red sandy pottery and glazed ware | Piedmont alluvial-fan terrace | Non-ancient city |

| 3 | 37°01′25.49″N, 99°34′26.08″E | ~0.7 km SW of Fusi City | Low mounds and exposed rammed layers | Dark-red sandy pottery, brown-green glaze | Second terrace on north bank of Qieji River | Peripheral settlement of Fusi City |

| 4 | 37°01′30.9″N, 99°36′14.5″E | ~1.2 km SE of Fusi City | Rammed-earth platforms and low wall remains | Decorated gray pottery with cord and grid patterns | Terrace of the Qieji River; flat terrain | Outer city of Fusi (east wall, southern section) |

| 5 | 36°52′15.00″N, 100°46′12.87″E | ~20 km from Xihai County City | Rammed-earth wall (height ~1 m) | Red sandy and brown-glazed pottery | Terminal fan terrace | Non-ancient city |

| 6 | 37°10′40.86″N, 99°44′10.32″E | ~16 km from Beixiangyang City | Elongated mound with residual rammed base | Dark-red sandy pottery, brown-green glaze | Junction of lake terrace and piedmont fan | Non-ancient city |

| 7 | 37°22′17.45″N, 98°48′55.93″E | ~4.5 km from Jinquan City | Earthen mounds with traces of compaction | Gray and glazed pottery, red sandy ware | Terrace near Buha River | Non-ancient city |

| 8 | 37°28′16.42″N, 98°36′8.20″E; 37°28′10.41″N, 98°35′56.38″E | ~200 m and 800 m from Dalai-Mane No. 2 City | No visible rammed-earth remains; covered by grass | No artifacts found; no cultural layer | Second terrace on north bank of Buha River | Ancient city remains (Dalai-Mane No. 3 and No. 4) |

Table 6.

Comparison between model-detected sites and field verification results in the Qinghai Lake Basin.