1. Introduction

In recent years, the remote sensing field has developed rapidly [

1], with video satellites emerging as a novel type of Earth observation satellite. These satellites are capable of persistent regional staring imaging, acquiring continuous video data of designated areas. This regional staring imaging capability allows the satellite to maintain observation over a specific region for an extended duration. As a result, they are particularly well-suited for monitoring regional dynamic changes [

2], including situational shifts, dynamic target reconnaissance and surveillance [

3], and assessing attack impacts. However, due to constraints in the data transmission process, satellite videos are often compressed and downsampled, leading to unintended loss of high-frequency information and limiting their utility across various applications. To address this issue, developing a practical approach, such as super-resolution (SR) techniques, is crucial for enhancing the spatial resolution of satellite videos.

SR, a fundamental low-level task in computer vision, aims to reconstruct high-resolution (HR) data from a single low-resolution (LR) observation [

4,

5,

6]. As an ill-posed problem, SR primarily focuses on enhancing spatial information, offering a practical solution to mitigate hardware constraints. Video super-resolution (VSR) extends image SR by reconstructing HR videos from LR video sequences, aiming to enhance perceptual quality. Unlike image SR, VSR is inherently more complex, as it requires simultaneous modeling of spatial and temporal information across misaligned video frames. Various approaches have been developed for this task. Early methods, inspired by image SR, often employed a sliding-window approach [

7,

8,

9,

10], reconstructing a target frame using 3–7 adjacent frames. However, because video sequences typically consist of dozens of frames, this approach captures only local temporal dependencies, leading to suboptimal performance. To model global temporal dependencies, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have gained increasing attention in VSR. Among these, bidirectional propagation neural networks have become a widely adopted paradigm. Notably, BasicVSR [

11] and BasicVSR++ [

12] have achieved remarkable performance by decomposing the VSR pipeline into four key components: propagation, alignment, aggregation (fusion), and upsampling.

Despite significant advancements in VSR methods, these approaches are not directly applicable to satellite videos. Compared to natural videos, satellite videos, characterized by diverse scenarios and small-scale targets, pose significantly more complex challenges, rendering the satellite video super-resolution (SVSR) task particularly demanding [

13]. First, satellite videos typically lack the rich texture and detail of natural videos, making feature extraction more challenging. Second, moving objects in satellite videos, which often occupy only a few pixels and exhibit subtle motion changes, pose challenges for capturing fine-grained motion information. These factors collectively make it challenging for mainstream alignment methods designed for natural videos to achieve precise alignment in SVSR. Specifically, mainstream alignment techniques are broadly categorized into explicit alignment (based on optical flow [

14]) and implicit alignment (based on deformable convolution network (DCN) [

15]). However, optical flow-based alignment relies on gradient information from frames, which is often insufficient for small and subtle motion moving objects in satellite video scenes. Meanwhile, it is sensitive to multi-scale small objects and complex boundary variations [

9]. Similarly, accurately estimating the subtle motion offsets of DCN for alignment becomes exceptionally challenging in such scenes, resulting in suboptimal feature alignment. Meanwhile, DCN-based alignment methods have been widely criticized for their unstable training dynamics, which often lead to inconsistent performance when applied in complex and highly varied scenarios. Consequently, an alignment compensation strategy that accounts for satellite video characteristics is essential to improve alignment accuracy in SVSR. On the other hand, satellite videos often feature numerous densely packed small-scale building structures, which readily generate artifacts. Meanwhile, the small size of objects makes it challenging to distinguish objects from artifacts, which is crucial for downstream tasks such as object detection and tracking. Therefore, enhancing edge reconstruction is crucial to improve the performance in SVSR.

In this paper, we address the aforementioned challenges from a frequency-domain perspective, leveraging the global representation capabilities of frequency-based models [

16]. To this end, we propose a novel Frequency-Aware Enhancement Network (FAENet) for SVSR, that focuses on alignment compensation and edge reconstruction in the frequency domain. Specifically, the proposed Frequency Alignment Compensation Mechanism (FACM) incorporates a frequency-domain distribution alignment function to achieve precise alignment compensation. In contrast to methods that perform alignment directly in the frequency domain [

17], the FACM is designed to compensate and enhance the output of existing alignment methods, thereby enabling them to effectively adapt to the unique motion characteristics of satellite video scenes. Notably, FACM is designed for seamless integration into existing VSR frameworks, eliminating the need for fine-tuning of the architecture, which significantly facilitates the adoption of VSR techniques for challenging satellite video applications. Additionally, the proposed Frequency Prompt Enhancement Block (FPEB) combines prompts with frequency-domain components not only to extract features [

16], but also to distinguish objects from artifacts, thereby enhancing edge reconstruction accurately. Extensive experiments demonstrate that FAENet significantly outperforms existing methods across two SVSR datasets. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

The proposed FACM employs frequency-domain alignment compensation for fine-grained frame alignment, enhancing the model’s ability to capture subtle motion. Additionally, it integrates seamlessly as a plug-and-play module into RNN-based natural VSR methods, enabling effective adaptation to satellite videos.

The proposed FPEB incorporates learnable prompts directly into the frequency domain. This design enhances the model’s capacity to differentiate genuine objects from high-frequency artifacts. As a result, it facilitates adaptive edge reconstruction in the spatial image domain.

Comprehensive evaluations on two satellite video datasets show that our method surpasses existing approaches in both quantitative and qualitative metrics. These results underscore the robustness and efficacy of the proposed framework in handling complex dynamic scenes, establishing a new benchmark for satellite video analysis.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on VSR and SVSR.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of our proposed method.

Section 4 presents the datasets, training details, experimental results, and analysis. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the conclusions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Natural Video SR

VSR builds upon single-image SR by jointly exploiting spatial and temporal information processing that poses a central challenge to the task. Generally, existing VSR methods can be categorized into two primary paradigms: sliding-window methods and RNN-based methods.

Sliding-window methods aggregate information from multiple neighboring LR frames to reconstruct a target frame, typically following the alignment, fusion, and reconstruction paradigm [

18]. Kappeler et al. [

19] developed models that leverage both spatial and temporal dimensions of videos to enhance spatial resolution and systematically evaluated multiple strategies for integrating video frames within a unified convolutional neural network (CNN). Caballero et al. [

20] proposed a spatio-temporal sub-pixel CNN that effectively utilizes temporal redundancies to optimize reconstruction accuracy while ensuring real-time computational efficiency. Jo et al. [

8] proposed an end-to-end DNN that generates dynamic upsampling filters and a residual image based on local spatio-temporal pixel neighborhoods, eliminating explicit motion compensation. Yi et al. [

21] proposed a novel progressive fusion network for VSR that leverages spatio-temporal information via an improved non-local operation, avoiding complex motion estimation and compensation, and proving more efficient and effective than existing direct fusion, slow fusion, or three-dimensional (3D) convolution strategies. In summary, while sliding-window-based methods have demonstrated considerable success in various video analysis tasks, they inherently suffer from a critical limitation: the reliance solely on local window information. This constraint prevents them from effectively capturing long-range dependencies across more extended temporal sequences. Consequently, this inherent architectural bottleneck has led to a noticeable performance plateau in these approaches. To mitigate this deficiency and facilitate the modeling of global context, RNNs are introduced as a compelling alternative.

RNN-based models seek to effectively leverage long-range dependencies by recurrently propagating comprehensive information from both past and future frames [

22]. For example, RBPN [

23] considered each context frame an independent information source, employing a recurrent encoder–decoder module to fuse spatial and temporal contexts derived from consecutive video frames. RSDN [

24] presented a recurrent unit composed of multiple two-stream structure-detail blocks, which facilitates selective utilization of the current frame’s hidden state information to bolster robustness against appearance variations and error accumulation. Liu et al. [

25] proposed a deformable motion alignment module to precisely estimate offsets, thereby efficiently aligning adjacent image frames using a small number of input frames. BasicVSR [

11] presented a streamlined pipeline that reconsiders four key components for VSR: propagation, alignment, aggregation, and upsampling. BasicVSR++ [

12] introduced second-order grid propagation and flow-guided deformable alignment, building upon the foundation of BasicVSR. In this work, we select these methods (BasicVSR, IconVSR, and BasicVSR++) as the compared methods. They represent the classics in RNN-based VSR frameworks, and since our proposed FAENet is also built upon the RNN architecture, benchmarking against them allows for a direct validation of our proposed methods.

In brief, RNN-based methods leverage long-range frame sequences to achieve superior performance in natural scenes. However, their direct application to satellite scenarios faces significant challenges due to distinct imaging characteristics. Mainstream approaches assume that moving objects exhibit large-scale motion and strong gradients, facilitating the capture of motion. However, this assumption is invalid in satellite videos, where the bird’s-eye view results in tiny object sizes (often occupying only a few pixels) and minimal motion, which severely impedes robust motion capture and alignment.

2.2. Satellite Video SR

As a subfield of VSR, SVSR has recently attracted increasing attention but remains underexplored compared to VSR due to challenges in data acquisition. Compared to the general scenario, satellite video suffers from greater degradation, and its wide scene characteristic also poses greater challenges for SVSR in reconstructing high-frequency details [

26]. Zhang et al. [

27] presented one of the first studies to utilize satellite video for SVSR, integrating both single- and multi-frame data. The multi-frame network was adapted from the classic general VSR network, EDVR [

7], and employs deformable convolutions for feature alignment. Furthermore, standard models such as VDSR [

28] and ESPCN [

29] were retrained on satellite video data to suit the SVSR task. Subsequently, greater efforts have been devoted to leveraging the distinct characteristics of remote sensing imagery to improve feature representation capabilities. For example, to address temporal redundancy in satellite video [

30], Liu et al. [

31] proposed an efficient framework that leverages local prior knowledge and nonlocal spatial similarity. He et al. [

32] proposed an OFEnet that employs 3D convolution to achieve temporal compensation. To optimize the reconstruction of high-frequency components, Jiang et al. [

33] proposed a deep distillation recursive network that performs feature distillation and high-frequency compensation across multiple network stages. Furthermore, Jiang et al. [

34] introduced a GAN-based SVSR approach to enhance high-frequency edge features and mitigate noise. To improve the detail of small objects in satellite video, Chen et al. [

35] modeled the LR airplane with a new reflective symmetry shape prior to extracting more complete features for VSR. To mitigate errors resulting from inaccurate motion estimation and alignment, Xiao et al. [

36] developed a novel fusion approach that integrates temporal grouping projection with multiscale deformable convolution alignment to optimize spatial resolution and generalization. Additionally, Xiao et al. [

9] employed local and global temporal differences to facilitate efficient and robust temporal compensation.

In short, recent SVSR methods have primarily focused on feature extraction and reconstruction in the image domain. However, satellite videos lack sufficient detail and exhibit lower image quality than natural ones. These approaches overlook fine-grained features from a frequency-domain perspective, which could amplify distinctions between objects and artifacts, thereby enhancing the capture of motion information and the reconstruction of detail.

2.3. Learning in Frequency Domain

Recently, frequency-based models have garnered significant attention in image and video processing due to their capability to capture global representations effectively. Commonly employed techniques for extracting frequency-domain information are the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT). The inherent multi-resolution property of the DWT enables it to effectively capture multi-scale features, while the FFT is well-suited for extracting global features [

37]. The FFT decomposes data into amplitude and phase components, while the DWT separates data into four distinct frequency sub-bands: a low-frequency component and three high-frequency components in the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions. Leveraging the unique properties of these transforms, researchers have extended their applications to various domains, including low-light image enhancement, SR, and image segmentation. Approaches that leverage frequency information can be broadly categorized into transform-domain modeling and frequency-domain-guided recovery approaches, based on whether interaction between feature and frequency domains. Approaches leveraging frequency information can be broadly categorized into transform-domain modeling and frequency-domain-guided recovery, depending on the interaction mechanism between the feature and frequency domains.

Transform-domain modeling involves transforming features into the frequency domain within the intermediate network layers, operating on the resulting frequency components, and then transforming them back. For example, Zhang et al. [

38] introduced a hierarchical feature restoration block to model wavelet frequency features, which considers the unique characteristics of distinct frequency sub-bands, establishing a robust model that fully exploits frequency domain features. Xiao et al. [

39] incorporated high-frequency cues into Mamba by dynamically selecting more informative frequency signals, thereby reducing computational complexity. Leveraging the global modeling capacity of the FFT [

40], Li et al. [

16] aggregated spatial-temporal information directly within the frequency domain, thereby enabling CNNs to effectively capture long-range dependencies. Zhu et al. [

17] captured motion relationships in the frequency domain to generate fine-grained details from aligned features, and utilized a frequency-aware contrastive loss that supervises reconstruction via separate high- and low-frequency groups. Yan et al. [

41] leveraged the generative capability of diffusion models to produce frequency priors, which are then used to reconstruct more reliable details. It is a wavelet-based Transformer block that significantly accelerates inference because DWT decomposes features into smaller and more compact frequency components for processing. Li et al. [

42] introduced multi-level wavelet transforms to extract pyramidal features and reduce the encoding cost of latent video diffusion models.

In contrast, frequency-domain-guided methods primarily perform recovery in the feature domain, utilizing frequency analysis to provide auxiliary guidance or constraints. For example, Xu et al. [

43] integrated high-frequency components with U-Net feature maps, using this connection to guide the precise insertion of details, which effectively mitigates output blurriness. Zhao et al. [

44] combined the original low-light image and its low-frequency component to search a new image space, achieving noise suppression and reducing its impact on feature encoding and interaction. Liu et al. [

45] generated amplitude residuals to bridge the gaps between hazy and clear domains without adding extra parameters, and proposed a phase correction module to eliminate unwanted artifacts.

As previously mentioned, several existing SR methods have incorporated frequency-domain information. However, they often process it in a non-discriminative manner, applying uniform operations across all frequency features without targeted modulation, thereby limiting performance in challenging satellite scenarios, such as those involving small, slow-moving targets and dense small buildings. Therefore, we incorporate learnable prompts to enhance the model’s sensitivity to discriminative information, improving edge reconstruction and artifact discrimination.

3. Methods

In this section, we first provide an overview of the proposed FAENet. Next, we introduce its key components, FACM and FPEB, which address alignment challenges in SVSR and enhance object-edge reconstruction, respectively. Finally, we present the loss function for this pipeline.

3.1. Overview

RNNs are a widely recognized framework in VSR. We select the comprehensive VSR framework [

46] as our baseline model. This framework is particularly advantageous as it integrates several classic VSR and SVSR models into a single architecture, providing a unified environment for training and testing to facilitate fair comparisons. Building upon this established architecture, we propose a novel SVSR model, termed FAENet, which integrates the proposed FACM and FPEB modules. Specifically, FACM includes a frequency-domain distribution alignment function designed to adapt alignment methods for satellite videos in a plug-and-play manner. Furthermore, FPEB is introduced to distinguish high-frequency textures from artifacts and enhance edge reconstruction. Let

frames of LR video sequence be denoted as

, and its corresponding reconstructed HR video sequence as

, where

is the length of the video. The FAENet architecture is illustrated in

Figure 1: (1) The model extracts features from the LR satellite video sequence

, where

C,

m, and

w represent channel, height, and width, respectively. (2) Alignment and feature fusion modules align neighboring frames and integrate forward or backward propagation features (

or

) with the current frame. (3) FACM combines current features (

) and propagation features (

) to compensate for alignment inaccuracies. (4) FPEB leverages frequency components and prompts to enhance edge reconstruction. Finally, the reconstruction module upsamples the LR sequence to an HR video sequence

, where

denotes the upscale factor. Moreover, the pixel shuffle layer upsamples the LR input video sequence.

3.2. Frequency Alignment Compensation Mechanism

As previously noted, mainstream alignment methods are primarily designed for natural videos with frontal perspectives. In such scenarios, moving objects typically exhibit large motion scales relative to the background, providing strong gradient information or distinct offsets that allow optical flow or DCN to capture motion effectively. In contrast, satellite videos capture information from a bird’s-eye view, where moving objects occupy only a few pixels and exhibit subtle, slow-motion characteristics. This results in weak gradient information, making it challenging for conventional spatial alignment methods to achieve high precision. To address this “insufficient alignment accuracy,” we propose alleviating the problem from a global perspective in the frequency domain. We introduce the FACM, a plug-and-play module that leverages a frequency-domain distribution alignment function to compensate for the limitations of spatial alignment in satellite scenarios.

In detail, the FACM takes the current features

(or

) and the propagation features

(or

) as inputs. For clarity, this section describes the process using the forward propagation pair

and

, noting that backward feature pair (

and

) undergo analogous processing. First, we utilize the 2D Haar DWT for feature decomposition. In the proposed FAENet, ‘DWT’ implies the Haar wavelet transform. The DWT yields four subbands: one low-frequency component (

) and three high-frequency components (

,

, and

). Since the

primarily contain structural information that remains relatively stable between frames, the FACM focuses exclusively on the high-frequency components to capture subtle motion details and minimize computational complexity. Consequently,

is excluded from the process, as shown in

Figure 1. To characterize the global statistical distribution of these high-frequency details [

16,

17,

45], we calculate the mean values

and

for each subband, formulated as:

where

and

represent the spatial dimensions of the frequency subbands. Here,

denotes the set of frequency-domain coefficients (e.g.,

, and

) for the current and forward frames. Similarly,

represents the corresponding feature maps.

To compensate for spatial misalignment, we propose a frequency-domain distribution alignment function

. The

acts as a statistical calibration function:

Specifically, we utilize the relationship between the global means to calibrate the reference feature. The alignment formulation is defined as:

where

represents the aligned high-frequency component

. The term

functions as a residual correction. When the frames are statistically well-aligned (i.e.,

), the correction term approaches 0, and the function naturally simplifies to preserving the target distribution

. Moreover, FACM degenerates into an optimization module for features, preventing signal degradation when alignment is already accurate. This formulation leverages the ratio of means to implicitly adjust the intensity of the propagation features to match the distribution of the current frame, thereby enhancing alignment accuracy globally.

is set to

for numerical stability. The components

and

are obtained similarly.

After compensating the three high-frequency components, they are concatenated and refined through a series of convolutional layers, average pooling, ReLU, and a sigmoid activation to generate a spatial modulation map. This map is then combined with the input features to produce the compensated output

. Finally, to robustly integrate this compensation with the original propagation features, we introduce a learnable parameter

. The final output of FACM is formulated as:

where

is a learning weight optimized end-to-end alongside the network parameters. This enables the model to adaptively determine the optimal balance between frequency-compensated features and original propagation features.

3.3. Frequency Prompt Enhancement Block

In this section, we introduce a key component of our proposed FAENet framework, the FPEB, designed to enhance edge reconstruction for small moving objects and background buildings in SVSR. It is widely recognized that satellite videos provide the advantage of continuous monitoring of specific areas, enabling adequate support for tasks such as object tracking and detection. However, the inherent characteristics of satellite videos restrict the accuracy of these applications. Specifically, (1) satellite videos typically capture a wide field of view, resulting in a dense arrangement of objects; (2) the frame quality is generally lower than that of natural videos; (3) moving objects occupy only a small portion of pixels. Such factors make SR results prone to artifacts and poor edges, making it difficult to distinguish objects clearly. To address this, we propose the FPEB module, which leverages visual prompts in the frequency domain to guide the network in prioritizing the restoration of object and building edges, thereby reducing interference in downstream tasks.

In general, edges correspond to high-frequency information, while content corresponds to low-frequency components. Therefore, high-frequency information is key to enhancing edge reconstruction. However, traditional frequency methods are sensitive to scene noise [

16], often failing to distinguish true object details from artifacts or noise. To overcome this, the proposed module incorporates visual prompts [

47,

48] to facilitate automatic learning of critical edge patterns. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the FPEB utilizes a prompt pool

to store frequency-domain priors. Here,

T denotes the number of prompts in the pool, and

r represents the inner rank of each prompt.

Specifically, after feature refinement (FR), we apply the DWT to extract high-frequency components. The process is formulated as follows:

where

comprises convolutional and LeakyReLU activation layers. The extracted high-frequency components

are flattened and passed through a routing strategy to generate a selection matrix. Subsequently, a LogSoftmax function is applied to compute the log probabilities, indicating the likelihood of each prompt in

being selected by the frequency components or the relevance of each prompt in

to the current inputs. To enable differentiable prompt selection, we apply the Gumbel-Softmax trick [

49] to the log probabilities, yielding a one-hot routing matrix

, where

is the flattened spatial resolution of LR frames. The specific frequency prompt

is then retrieved through matrix multiplication, acting as a lookup mechanism:

Finally, we concatenate the selected frequency prompt P with the output of . This learned prompt serves as a guiding cue, dynamically emphasizing frequency regions corresponding to genuine object edges while suppressing artifacts or noise. This mechanism significantly strengthens the network’s ability to reconstruct fine-grained structures in complex satellite scenes.

3.4. Loss Function

We adopt the Charbonnier penalty function [

50] to optimize our network. This function provides a differentiable, smooth approximation of the

loss while offering robustness comparable to that of the

loss, effectively reducing the influence of large errors and emphasizing smaller ones. This makes it particularly effective for handling outliers in SR tasks [

51]. The loss function is as follows:

where

is the ground truth (GT) frame and

is a constant which is set to

.

4. Results

This section first introduces two satellite video datasets and evaluation metrics. It then elaborates on the training procedure, followed by a comparison of our proposed approach with state-of-the-art (SOTA) VSR and SVSR models and result analysis. Finally, we conduct comprehensive ablation experiments to validate the rationale and effectiveness of our method.

4.1. Satellite Video Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

Satellite Video Dataset

To thoroughly assess our SVSR method against SOTA approaches, we select two publicly accessible satellite video datasets for experimentation. The Jilin-189 dataset, derived from Jilin-1 satellites, offers a spatial resolution of 1 m, a frame rate of 25 frames per second, and video durations of 20 to 30 s, with each video containing 100 frames at a resolution of

pixels. Accessible via Jilin-189 (

https://github.com/XY-boy/LGTD?tab=readme-ov-file, 10 October 2025), the dataset comprises 189 training clips and 12 testing clips. For clarity, we label these testing clips as sequence 000 to sequence 011. Meanwhile, we set the HR and LR patch sizes for training to

and

, respectively, and for testing to

and

, respectively.

The SAT-MTB-VSR (

https://github.com/Alioth2000/RASVSR, 11 September 2025) dataset, derived from the SAT-MTB satellite video multitask benchmark dataset acquired by the Jilin-1 satellite, comprises 431 video clips, each consisting of 100 consecutive frames with a resolution of

pixels. Of these, 413 clips are allocated for training and 18 for validation, sourced from distinct original videos. For clarity, we label these testing clips as sequence 000 to sequence 017. The HR and LR patch sizes for training and testing settings are the same as the previous dataset.

To rigorously evaluate the quality of VSR outputs, we employ the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and the structural similarity index measure (SSIM) to quantify the performance of all methods objectively. The learned perceptual image patch similarity (LPIPS) [

52] is used to evaluate the perceptual quality of reconstructed videos. Notably, the PSNR and SSIM metrics are calculated across all three RGB channels rather than the Y channel of the YCbCr color space. Higher PSNR and SSIM values indicate better performance, and the lower LPIPS values indicate better perceptual performance.

4.2. Training Details

Our network is implemented using the PyTorch 2.7.1 framework. Following previous work, we employ bicubic interpolation to downsample video frames and generate LR frames. Our approach builds upon the open-source RASVSR framework [

46]. The network is trained on four NVIDIA RTX 4090d GPUs. For fair comparison, we set the batch size to 4 for both our method and all compared methods. The length of the video sequences is fixed at 60 frames, and the compared methods adhere to their official code settings. We use the Adam optimizer [

53] with an initial learning rate of

and adopt the Cosine Annealing Warm Restarts strategy [

54] to adjust the learning rate. Training is conducted for a total of

iterations. For the optical flow network, SpyNet, we utilize pretrained weights with fixed parameters for the first

iterations, after which they are fine-tuned with a learning rate one-quarter of the initial value. All experiments are conducted exclusively at a

scaling factor.

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

To further illustrate the reasonableness and effectiveness of the algorithms in this paper, comparisons are made with some popular and currently available algorithms, including Bicubic, BasicVSR [

11], IconVSR [

11], BasicVSR++ [

12], RASVSR [

46], DVSRNet [

55], and MADNet [

18]. For a fair comparison, we utilize the baseline source code from [

46] to train BasicVSR [

11], IconVSR [

11], BasicVSR++ [

12], and RASVSR [

46]. The remaining models are obtained from their official repositories. All results are evaluated at their best epoch to ensure optimal performance.

4.4. Results on Jilin-189 Dataset

Table 1 presents the quantitative results of all compared methods across 12 scenes, along with their average performance on the Jilin-189 test set. Our FAENet outperforms existing approaches, achieving the highest average values across two metrics, with improvements of 0.08 dB in PSNR and 0.0007 in SSIM over the second-best method. These results demonstrate that our method effectively restores high-quality, realistic details from LR sequences. DVSRNet introduces a new alignment method that fails to account for the specific characteristics of satellite videos, leading to suboptimal performance. When compared to methods using the same number of input frames and RNN-based architectures, such as RASVSR and MADNet, which perform alignment via DCN and optical flow, respectively, they are challenging to capture motion information in satellite scenarios featuring tiny moving objects and dense building backgrounds. In contrast, our approach integrates alignment compensation information, achieving a superior balance between computational efficiency and performance, as evidenced in Table 5. This demonstrates the effectiveness of FACM in capturing subtle motion information.

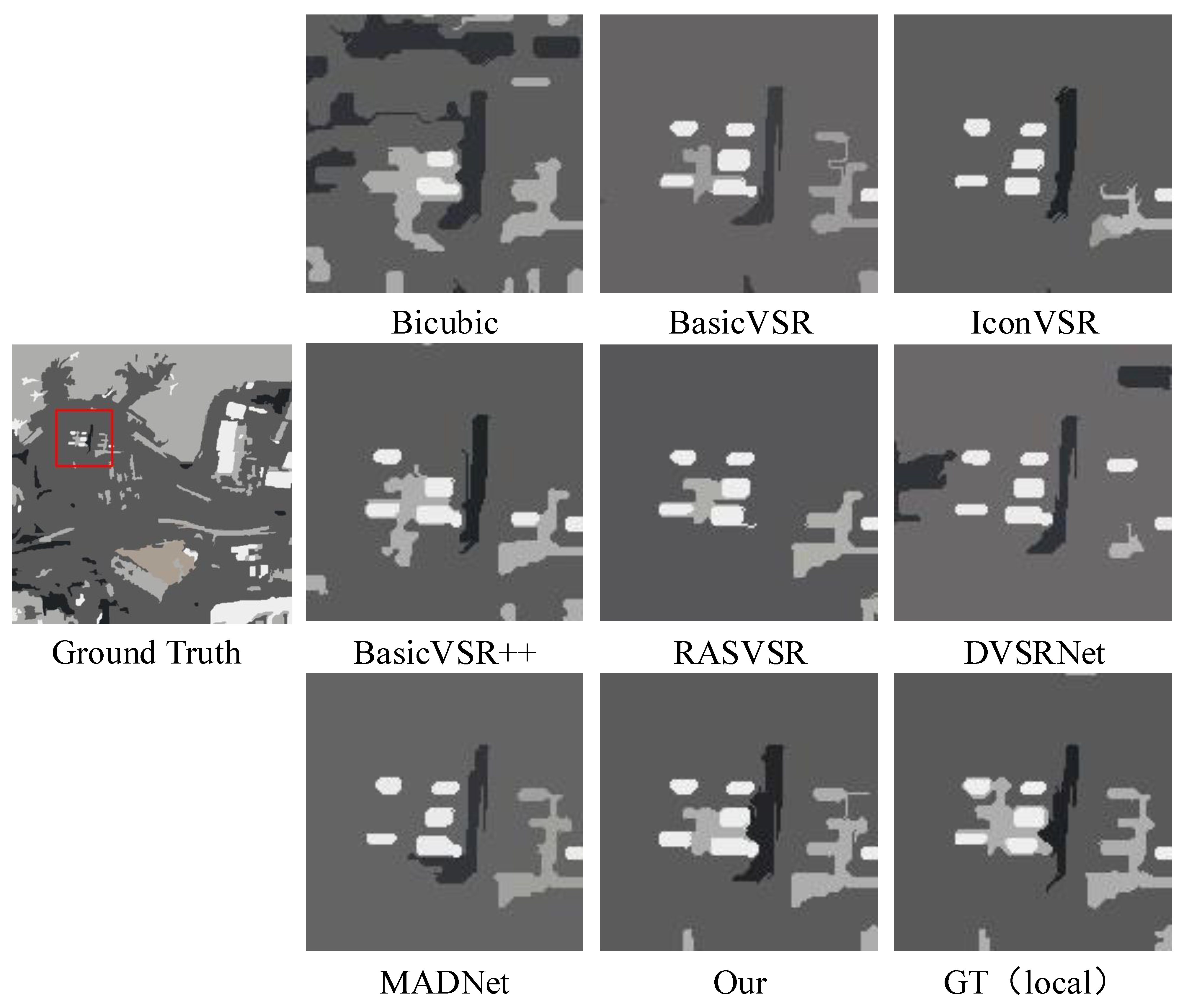

To comprehensively demonstrate the effectiveness of our models, we have provided visual comparison results in

Figure 2. The first and fourth rows display the scenes from test clips 001 and 005, respectively. Meanwhile, the second and fifth rows present randomly selected local regions with enlarged results for enhanced visualization, while the third and last rows display their corresponding error maps computed relative to the ground truth. It can be seen that all results are better with bicubic interpolation. BasicVSR, IconVSR, and DVSRNet present various distortions in structural details. Although our method’s performance is comparable to that of MADNet, it produces sharper edges. This improved edge reconstruction is facilitated by the FPEB module, which consistently prioritizes edge sharpness across diverse scenarios.

To better visualize the results, we present absolute error maps of locally enlarged regions. Specifically, red regions indicate maximum deviation from the ground truth, while blue regions denote close alignment with it. Analysis of the error maps reveals that BasicVSR and IconVSR exhibit larger red areas, corresponding to structural distortions in the enlarged RGB regions. As optical flow-based alignment methods, these approaches confirm that their direct application is unsuitable for satellite videos due to challenges in capturing motion information. BasicVSR++ and RASVSR exhibit fewer red regions in their error maps; however, their overall colors are lighter than ours, indicating inferior reconstruction in global structural fidelity. These methods rely on DCN-based alignment, which often results in accumulated misalignment errors in SVSR. Notably, our method significantly reduces the number of red regions compared to others, demonstrating that our alignment compensation mechanism and frequency-domain prompts effectively reconstruct ground object contours with enhanced textures and structures, thereby achieving closer visual alignment with the ground truth.

4.5. Results on SAT-MTB-VSR Dataset

Table 2 presents the quantitative results for all video clips and their average performance on the SAT-MTB-VSR dataset. This dataset is larger than previous and includes more scenes featuring dense buildings and objects. Notably, the dataset is derived from satellite video tracking of small objects, leading to a higher prevalence of tiny moving objects and introducing significant alignment challenges. Under these demanding conditions, our proposed method outperforms existing approaches in 13 of the 18 evaluated scenes in terms of PSNR. BasicVSR++ and RASVSR rely on DCN-based alignment methods that perform alignment at the feature or image level. This strategy proves unsuitable for lower-quality satellite videos, primarily because DCN may extract inaccurate offset estimates from potentially noisy or LR inputs. In such conditions, misalignment artifacts amplify during propagation, leading to ghosting effects and degraded temporal consistency in SR sequences. BasicVSR and IconVSR rely on optical flow-guided alignment to aggregate temporal information. This design assumes access to reliable motion cues derived from high-contrast, large-displacement scenarios typical in videos. However, satellite video often contains small, slowly moving objects, rendering optical flow estimators prone to failure. In contrast, our method underscores an alignment compensation mechanism at a finer, more distinctive level in the frequency domain to reduce misalignment accumulation in complex satellite scenes, achieving superior average PSNR and SSIM, demonstrating its effectiveness and robust generalization capabilities. Furthermore, compared to the second-best model, MADNet, our approach improves PSNR by 0.1 dB and SSIM by 0.0004, which demonstrates the superiority of our FAENet.

Figure 3 illustrates the visual results of various compared methods on test clips 003 (first row) and 010 (fourth row) from the SAT-MTB-VSR test set. The second and fifth rows present their corresponding enlarged local regions, with error maps computed for these regions displayed in the third and last rows to enhance visualization. From the enlarged results, we can see that ours are sharper and the details are more accurate. In the visual results, both IconVSR and DVSRNet demonstrate a noticeable loss of fine details, failing to preserve intricate features in the reconstructed images. In contrast, MADNet, while maintaining overall structural integrity, tends to produce blurred edges, resulting in a less sharp appearance of object boundaries. In summary, our proposed FAENet delivers exceptional performance in reconstructing objects and background structures, demonstrating the high effectiveness of frequency-domain alignment compensation and prompts for detailed reconstruction.

To better visualize fine-grained differences in visual results, we present absolute error maps that highlight reconstruction errors relative to the ground truth. The third row, derived from the 003 clip, reveals varying degrees of reconstruction errors across methods. Featuring a complex scene with dense trees, a highway, and landmarks, the 003 clip poses significant challenges to accurate edge reconstruction. Other methods exhibit inferior performance, with expanded red and yellow regions in locally enlarged images indicating suboptimal structural reconstruction. In contrast, our approach achieves the fewest errors, demonstrating superior reconstruction quality. This advantage stems from our proposed FPEB’s ability to guide the model to prioritize edge capture, regardless of background complexity or the presence of moving objects, via frequency-domain prompts, thereby further validating the robust generalization capability of our method across diverse and complex scenes.

4.6. Evaluation on Perceptual Quality (LPIPS)

The quantitative results in terms of LPIPS are reported in

Table 3. As shown in

Table 3, the proposed FAENet achieves the best average performance on both test sets. Specifically, FAENet attains average scores of 0.0257 on the Jilin-189 dataset and 0.0238 on the SAT-MTB-VSR dataset, outperforming the second-best method, MADNet, by margins of 0.0005 and 0.0002, respectively. These observations highlight the superior capability of FAENet in recovering satellite videos with high perceptual quality and structural details.

4.7. Ablation Studies

In this section, we first perform ablation studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the core modules, FACM and FPEB. Next, we assess the generalization capability of FACM. We then investigate additional factors influencing the network’s performance and discuss their implications. Finally, we validate the effectiveness of our SVSR methods through downstream tasks. Notably, all our ablation studies were conducted on the Jilin-189 dataset, using a consistent batch size of 4 across all experiments. The number of frame inputs for each algorithm is specified in tables.

4.7.1. The Effectiveness of FACM and FPEB

In this section, we validate the effectiveness of the two proposed key modules: the FACM and the FPEB. The average results are presented in

Table 4. The FACM is designed to enhance alignment accuracy, which is a critical operation in VSR. For RNN, effective alignment across the entire video sequence is essential, as misalignment can lead to significant error accumulation, rendering the results unusable. The FACM addresses this by compensating for alignment inaccuracies, which is particularly important given the discrepancies between natural videos and satellite videos, where the latter often present unique challenges due to their distinct characteristics. As shown in the comparison between the first and second rows of the

Table 4, the inclusion of FACM improves the PSNR by 0.56 dB and the SSIM by 0.0046, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing alignment accuracy through the frequency-domain distribution alignment function, which provides fine-grained alignment compensation. The FPEB uses frequency-domain prompts to differentiate between artifacts and objects, thereby improving edge reconstruction. As indicated in

Table 4, the incorporation of FPEB results in a performance improvement of 0.54 dB in PSNR and 0.0046 in SSIM, confirming the effectiveness of FPEB in enhancing the quality of reconstructed edges. Finally, integrating the FACM and FPEB significantly enhances the overall performance of the proposed method. By combining FACM’s ability to improve alignment accuracy and FPEB’s capability to refine edge reconstruction through frequency-domain prompt utilization, the model achieves superior results in both PSNR and SSIM, as evidenced by the quantitative improvements reported in

Table 4. This synergistic incorporation of FACM and FPEB underscores their contributions to robust SVSR, particularly in challenging satellite video scenarios.

4.7.2. Complexity on Model Complexity

We evaluate model complexity based on two metrics: floating-point operations (Flops) and parameters (Para). Specifically, Flops represent the total number of addition and multiplication operations performed by the model, with higher counts indicating greater computational complexity. Para refers to the number of trainable parameters in the model.

Table 5 presents the complexity comparison of our method against six SOTA methods. For a fair comparison, we first consider RASVSR, MADNet, and our proposed FAENet, all using an input sequence length of 60 frames. Our method achieves the best performance metrics while maintaining moderate complexity among these three, striking an effective balance between performance and computational efficiency. This superior performance is attributed to the FACM of the proposed FAENet. The FACM is specifically designed to account for the unique characteristics of satellite video scenarios (i.e., subtle motion and tiny moving objects) to implement effective alignment compensation. In contrast, the alignment methods employed by RASVSR and MADNet did not incorporate such a scenario-specific consideration, leading to suboptimal results. Compared to methods with shorter input sequence lengths, our approach ranks third in terms of Para while delivering the best performance, demonstrating clear advantages in both efficacy and efficiency.

4.7.3. Generalization of FACM

As previously mentioned, FACM is a plug-and-play module that can be integrated into methods derived from natural VSR algorithms, enabling their adaptation for SVSR tasks by compensating for alignment errors, thus enhancing alignment accuracy and overall performance. Therefore, we conduct the ablation study to evaluate the generalization of FACM. Specifically, we integrated FACM into four approaches without any fine-tuning of their frameworks. The results, including Flops, Para, PSNR, and SSIM, are presented in

Table 6. The paired comparisons demonstrate that adding FACM improves PSNR and SSIM to varying degrees, accompanied by a marginal increase in Flops and Para. BasicVSR and IconVSR rely on optical flow estimation for alignment, while BasicVSR++ and RAVSR employ DCN to achieve alignment. The incorporation of FACM into these two mainstream alignment methods results in consistent performance improvements, as evidenced by enhanced PSNR and SSIM metrics, demonstrating the effectiveness and strong generalization capability of the proposed alignment compensation mechanism.

4.7.4. The Length of Input Sequence

To ensure the best effectiveness of input sequence length, we conducted experiments with sequence lengths ranging from 7 to 75 frames, as reported in

Table 7. For a fair comparison, we maintained a consistent batch size across all experiments. The results demonstrate that increasing the lengths of the training and testing sequences improves SVSR performance. Models trained on 7- and 15-frame sequences perform similarly, whereas extending the sequence to 60 frames significantly improves PSNR, indicating that SVSR benefits from aggregating information across more extended sequences because of its inherently lower image quality compared to natural videos. However, an excessively long sequence may lead to information redundancy, resulting in increased computational complexity with minimal performance gains, as observed with a sequence length of 75 frames. To achieve a trade-off between performance and complexity, we ultimately set the input sequence length to 60 frames.

4.7.5. The Hyperparameters of the Number of Prompts in FPEB

One of the core components of FPEB is the learnable prompts, which enhance object edges in conjunction with the high-frequency domain. Two hyperparameters govern their performance: the prompt pool size,

T, and the inner rank,

r. In this section, we conduct ablation experiments to evaluate the impact of varying

T and

r on SVSR performance. To accelerate the training process, we obtain all results using an input sequence length of 7 frames, which maintains trend consistency with a 60-frame sequence. As shown in

Table 8, when

r is small, performance exhibits a slight downward trend. Conversely, when

T is small, reducing the prompt pool size sometimes leads to a slight performance increase but presents instability. Therefore, we select

, as it yields the optimal PSNR.

4.7.6. Temporal Consistency Analysis

In the context of VSR, temporal consistency plays a critical role in determining reconstruction quality. To illustrate this, we compare temporal profiles between our method and other approaches in

Figure 4, generated by horizontally stacking pixel rows across consecutive frames from the Jilin-189 dataset. The results reveal that Bicubic, IconVSR, and DVSRNet exhibit discontinuities in the output video, while MADNet, BasicVSR, and RASVSR display slight flickering artifacts. Benefiting from our FACM, FAENet effectively aggregates richer information from video frames, achieving smoother temporal transitions.

4.7.7. Evaluation on Downstream Segmentation Task

To rigorously verify the quality of edge reconstruction, we conducted an evaluation on a downstream segmentation task, as segmentation necessitates higher edge fidelity than detection or tracking. Using an unsupervised segmentation method [

56] on the Jilin-189 dataset, we measured performance via the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and Pixel Accuracy (PA), as shown in

Table 9. Our method outperforms comparison methods in both metrics, confirming that the FPEB module effectively preserves intricate edges and suppresses artifacts. Furthermore, as illustrated in

Figure 5, our generated segmentation maps most closely approximate the GT. In contrast, other compared methods exhibit noticeable segmentation errors.

5. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to address the unique challenges of SVSR, specifically the difficulties in aligning tiny, slow-moving objects and reconstructing sharp edges. Our experimental results on the Jilin-189 and SAT-MTB-VSR datasets demonstrate that the proposed FAENet significantly outperforms existing SOTA methods.

5.1. Relationship Between Previous Studies and the Working Hypotheses

On one hand, previous studies, such as BasicVSR and IconVSR, rely heavily on optical flow for alignment. While effective for natural videos, our results indicate that these methods struggle in satellite scenarios, leading to unsatisfactory performance. This confirms our working hypothesis that motion estimation in the image/feature space is insufficient for tiny and slow-moving targets. In contrast, our FACM operates on the global statistics of frequency subbands. The superior performance of FAENet suggests that alignment in the frequency domain provides a more robust, “coarse-to-fine” compensation strategy that effectively corrects the misalignment errors prone to occur in spatial-domain methods.

On the other hand, satellite videos inherently lack rich texture and feature dense buildings, often leading to blurring or artifacts. While traditional frequency-domain methods are susceptible to high-frequency noise/artifacts, our FPEB mitigates this by introducing a dynamic selection mechanism implemented through visual prompts. The significant improvement in PSNR and the superior performance in downstream segmentation tasks validate that FPEB is successful. It effectively captures critical structural details even in the presence of noise/artifacts, thereby enhancing edge reconstruction fidelity.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

While our method generalizes well across diverse satellite scenes, it relies on supervised training with large-scale paired HR and LR data. Future work could investigate unsupervised adaptation techniques to fine-tune the frequency prompts for unseen sensor data without requiring paired ground truth, thereby enhancing cross-sensors/scenes generalization. In addition, although FAENet achieves a favorable trade-off between performance and complexity compared to advanced models like MADNet, the total computational cost remains non-negligible for real-time processing. Future research will focus on optimizing the architecture, potentially through network quantization or distillation, to enable efficient deployment on resource-constrained satellite edge devices.