InSAR-Based Multi-Source Monitoring and Modeling of Multi-Seam Mining-Induced Deformation and Hazard Chain Evolution in the Loess Gully Region

Highlights

- The InSAR-based multi-source monitoring and modeling framework captured the spatiotemporal evolution of multi-seam mining-induced deformation.

- Multi-source observations demonstrated that fissure development, slope responses, and hazard-chain evolution are strongly synchronized with mining progression.

- The adopted multi-source monitoring and modeling framework provides a practical reference for improving deformation assessment in multi-seam mining regions.

- The clarified spatiotemporal evolution of hazard chains offers scientific guidance for mine planning and early warning in gully landform regions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

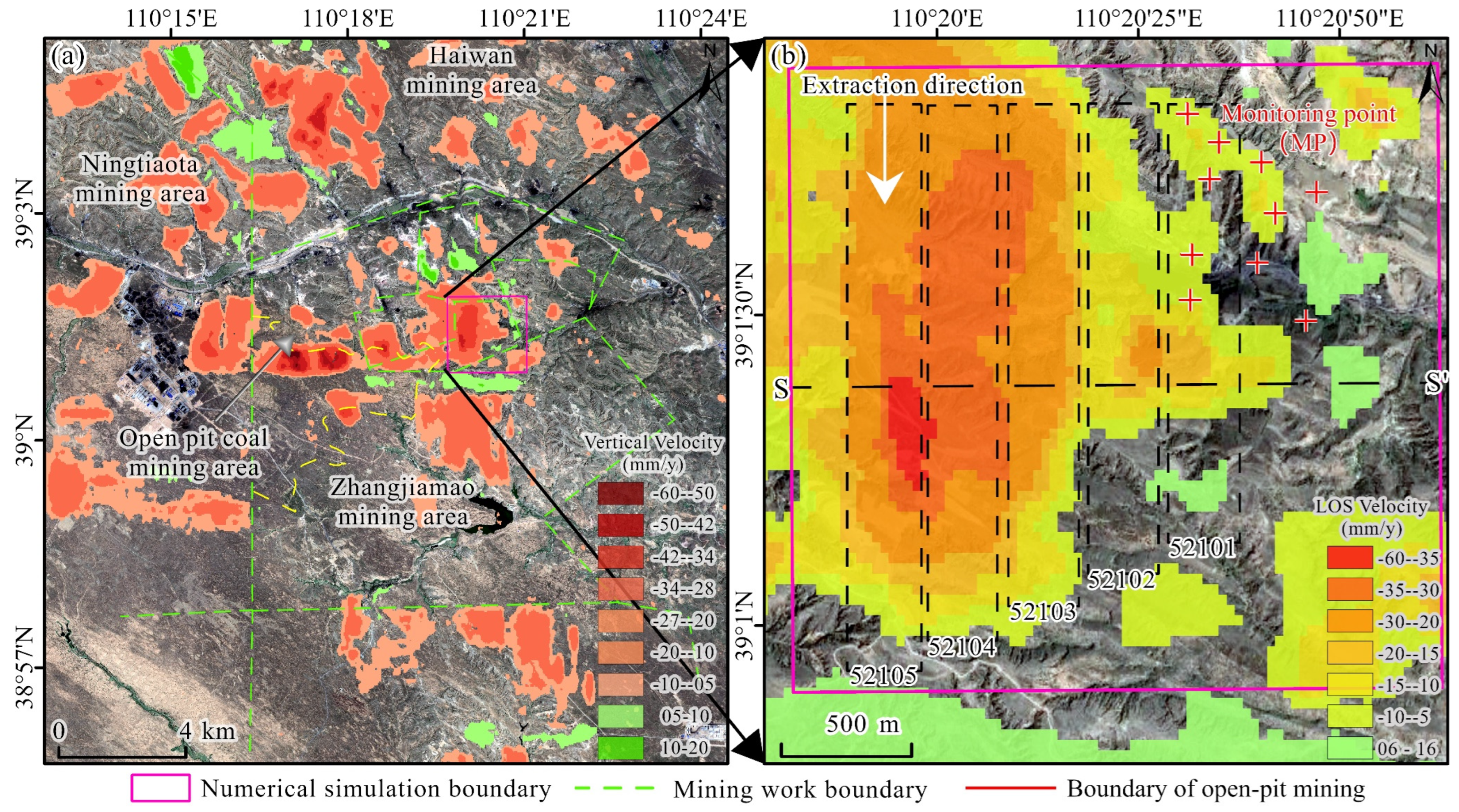

2. Study Area

2.1. Geologic Conditions

2.2. Mining Conditions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Workflow

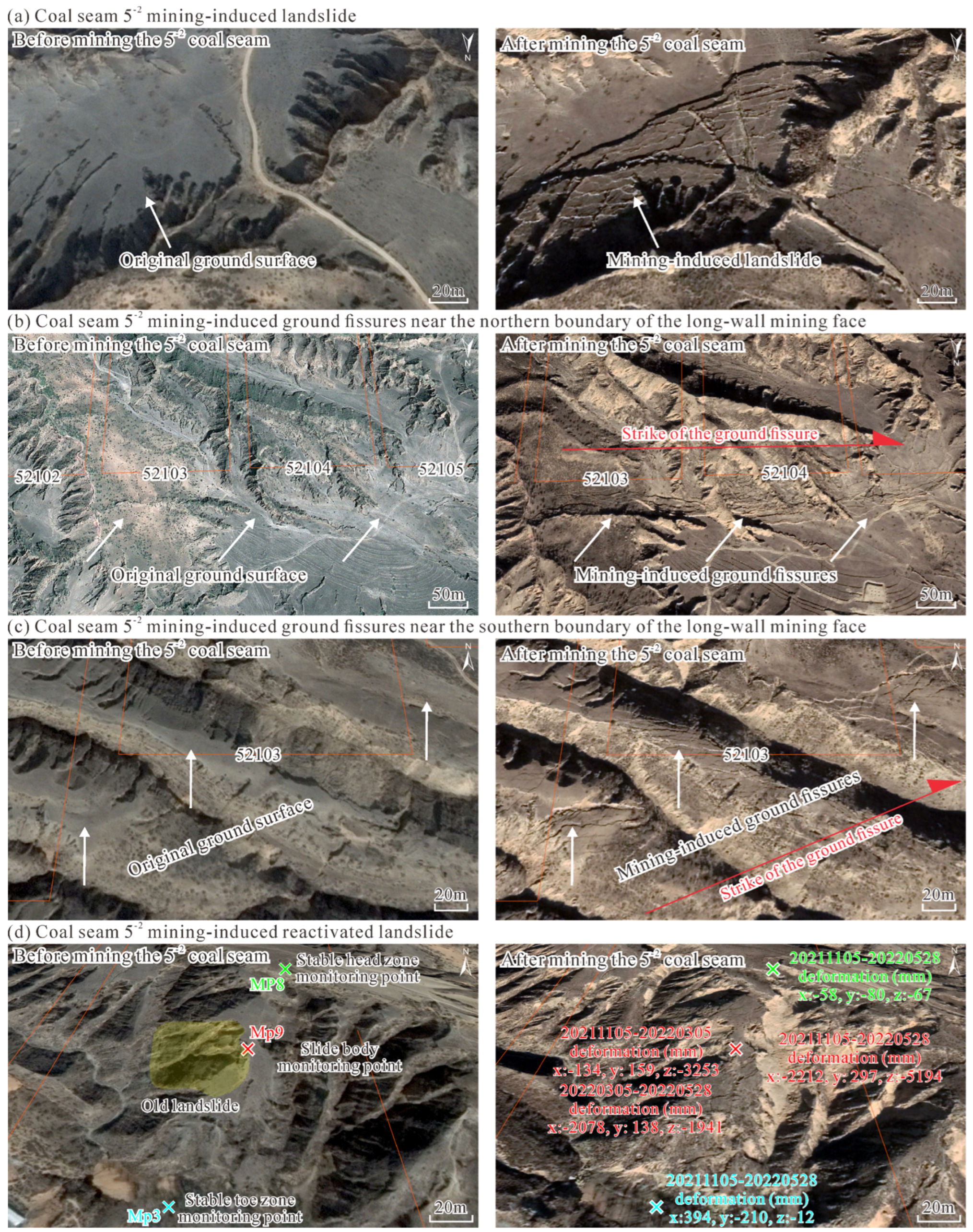

3.2. Site Investigations

3.3. Combined Interferogram Stacking and SBAS Approach

3.4. Simulation

3.4.1. Simulation Method and Parameters

3.4.2. Numerical Model and Modeling Scheme

4. Results

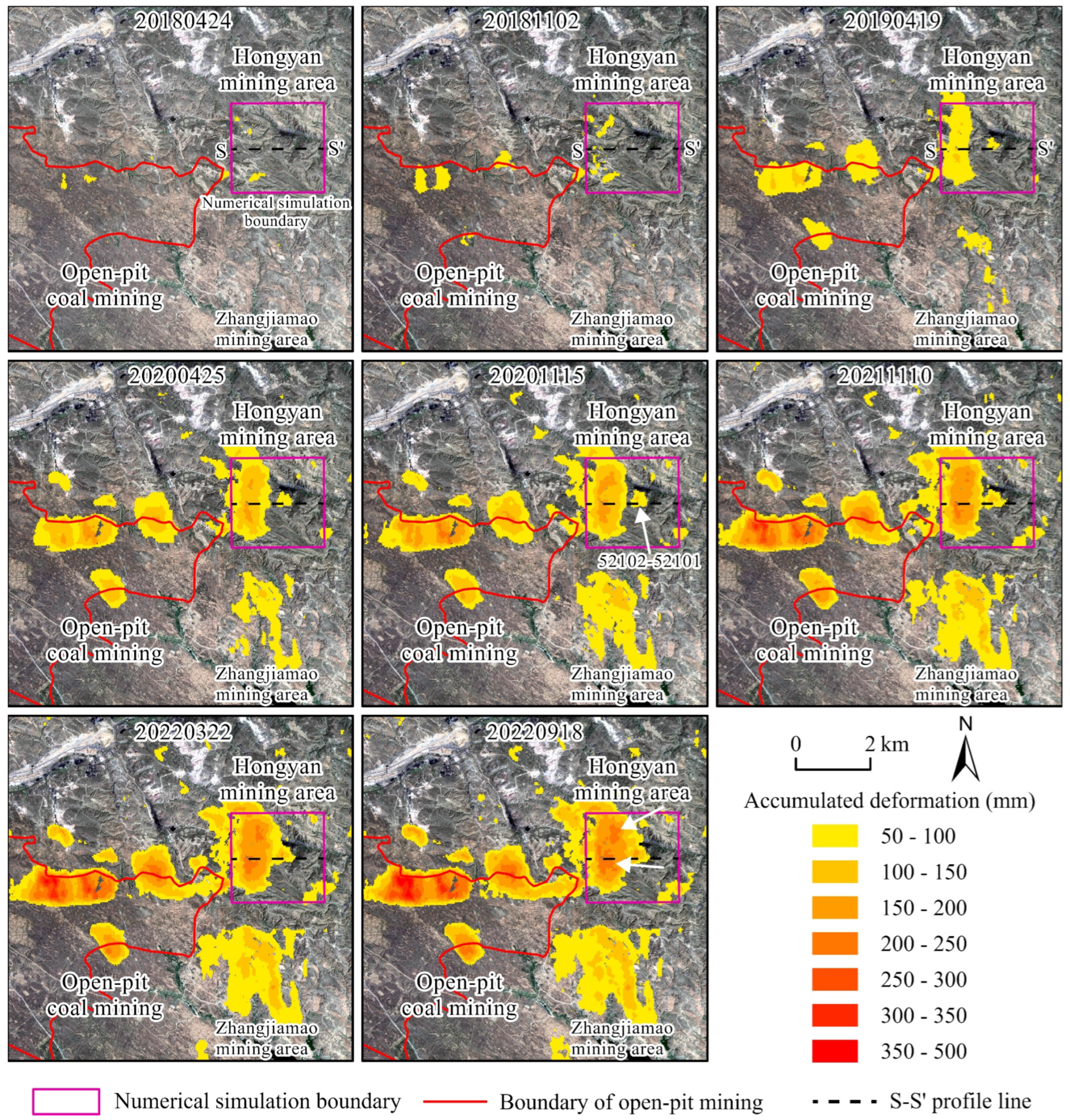

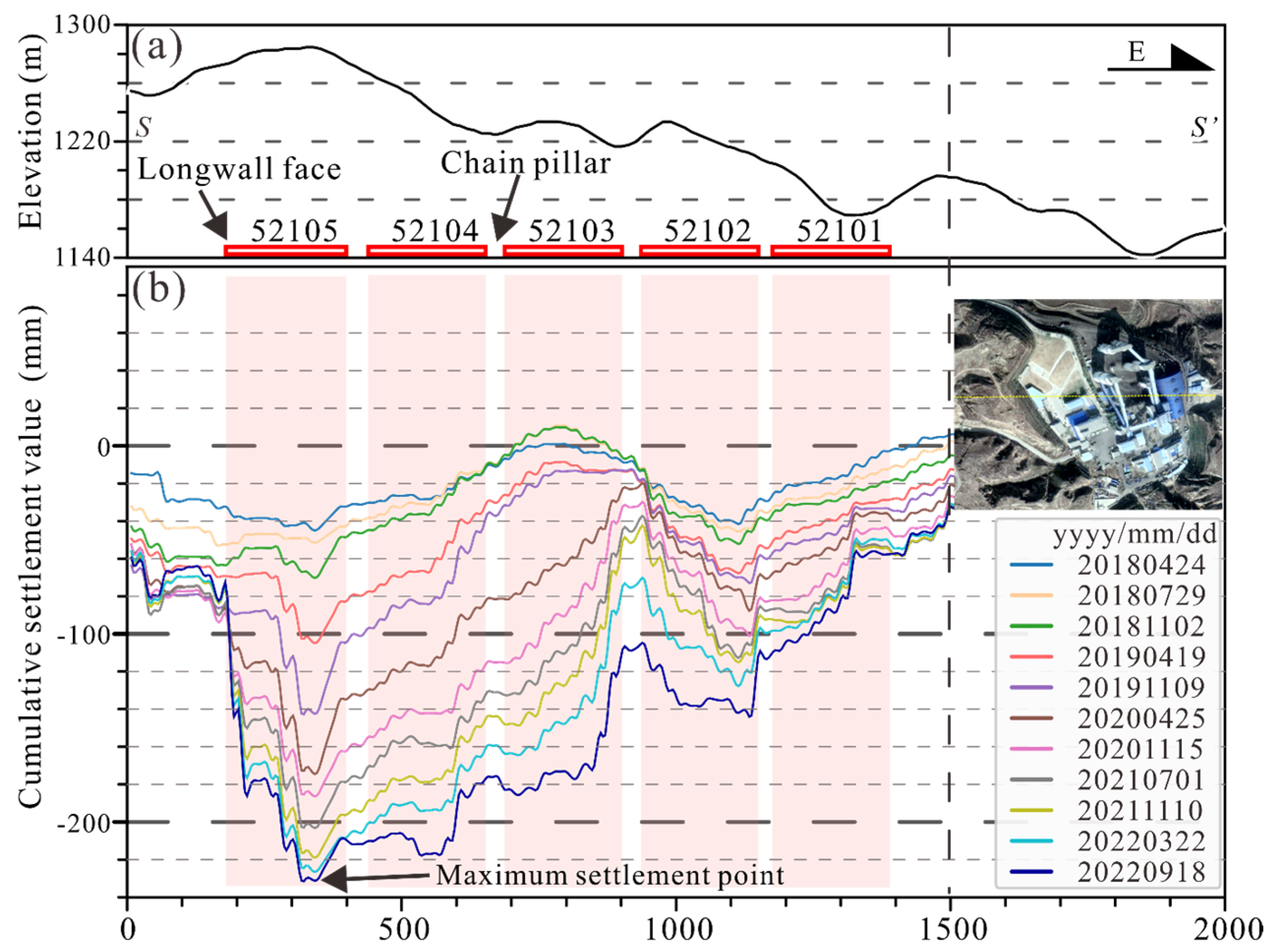

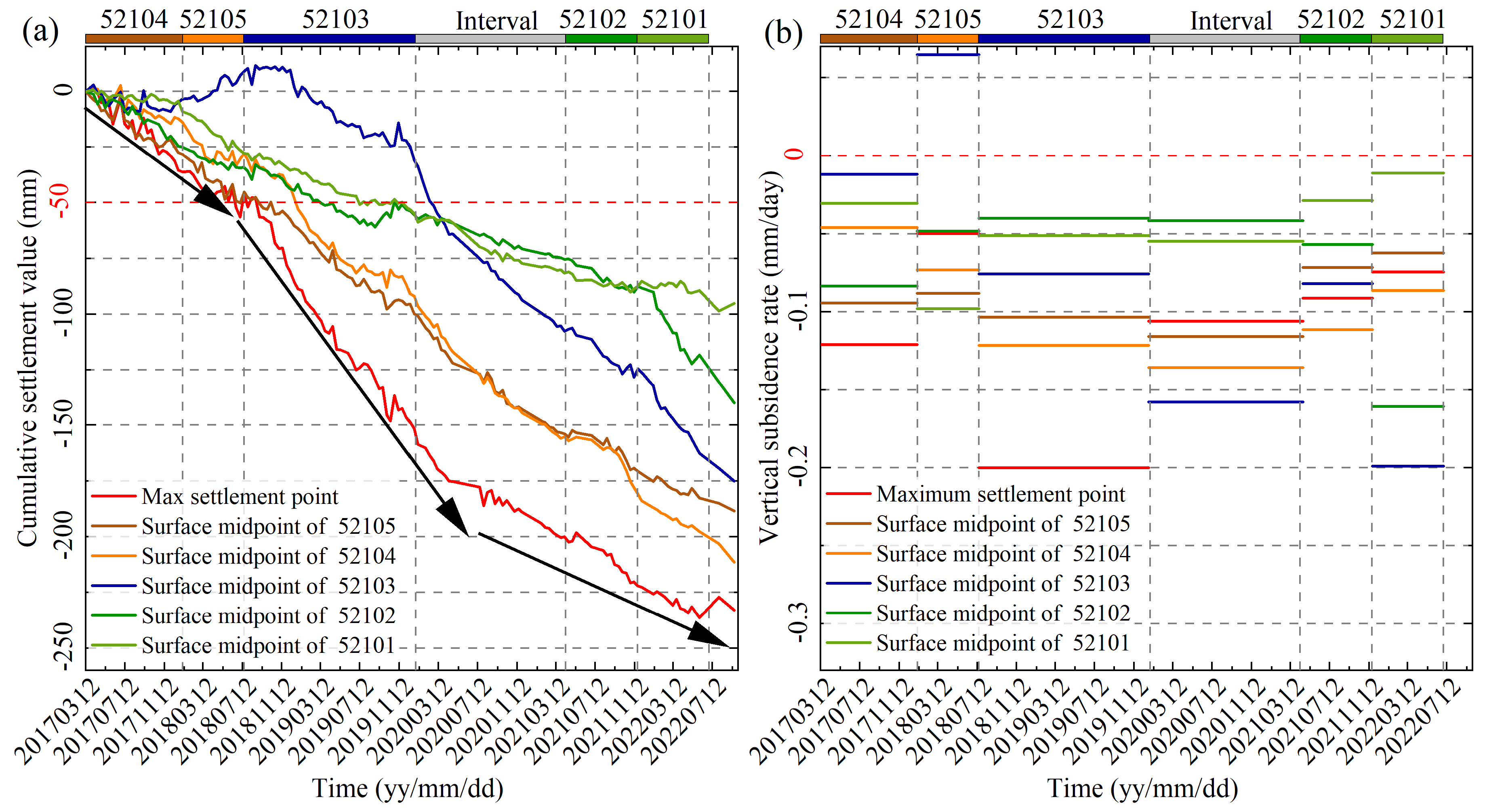

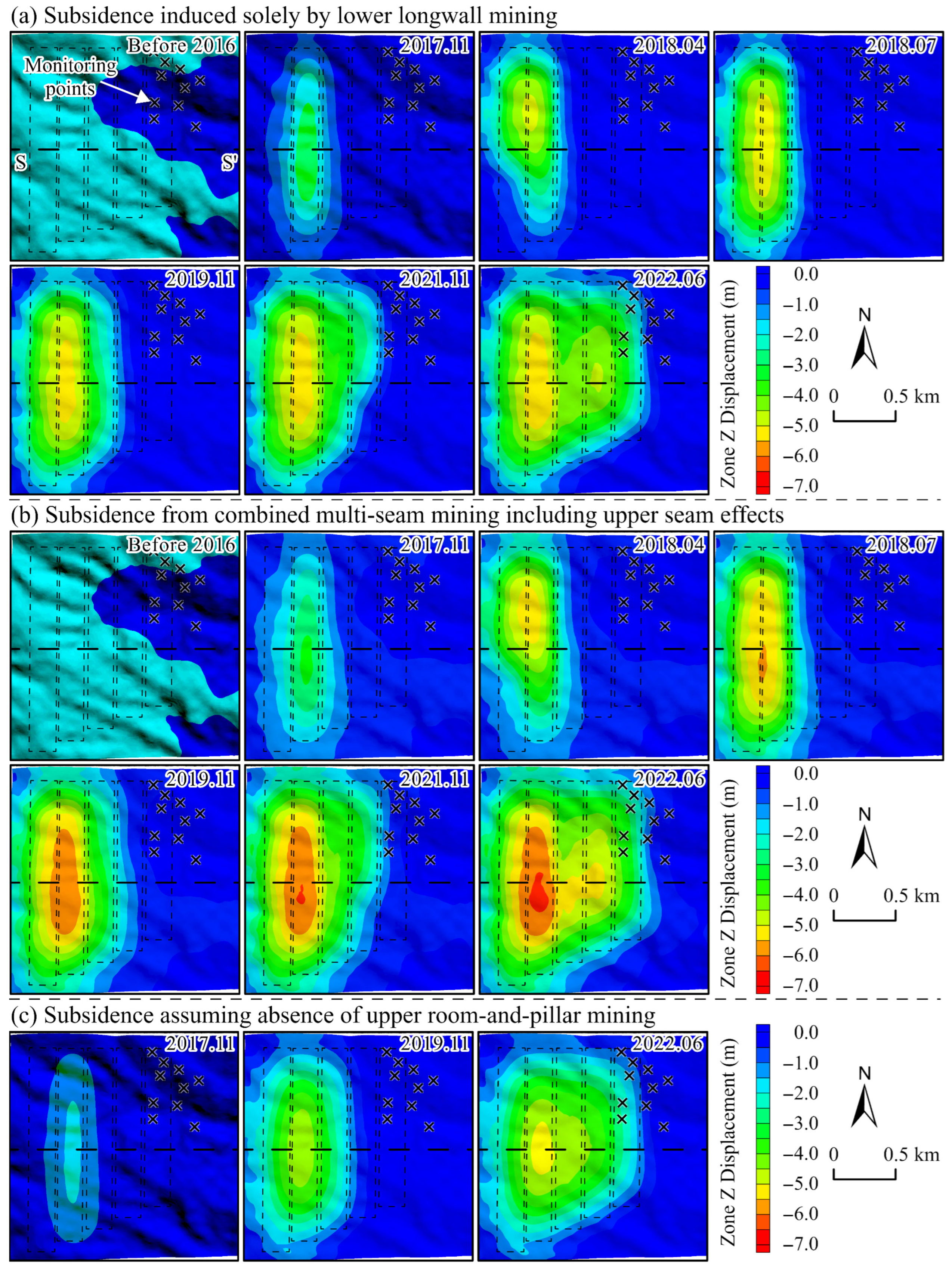

4.1. Surface Deformation

4.2. Mining-Induced Surface Multi-Hazards

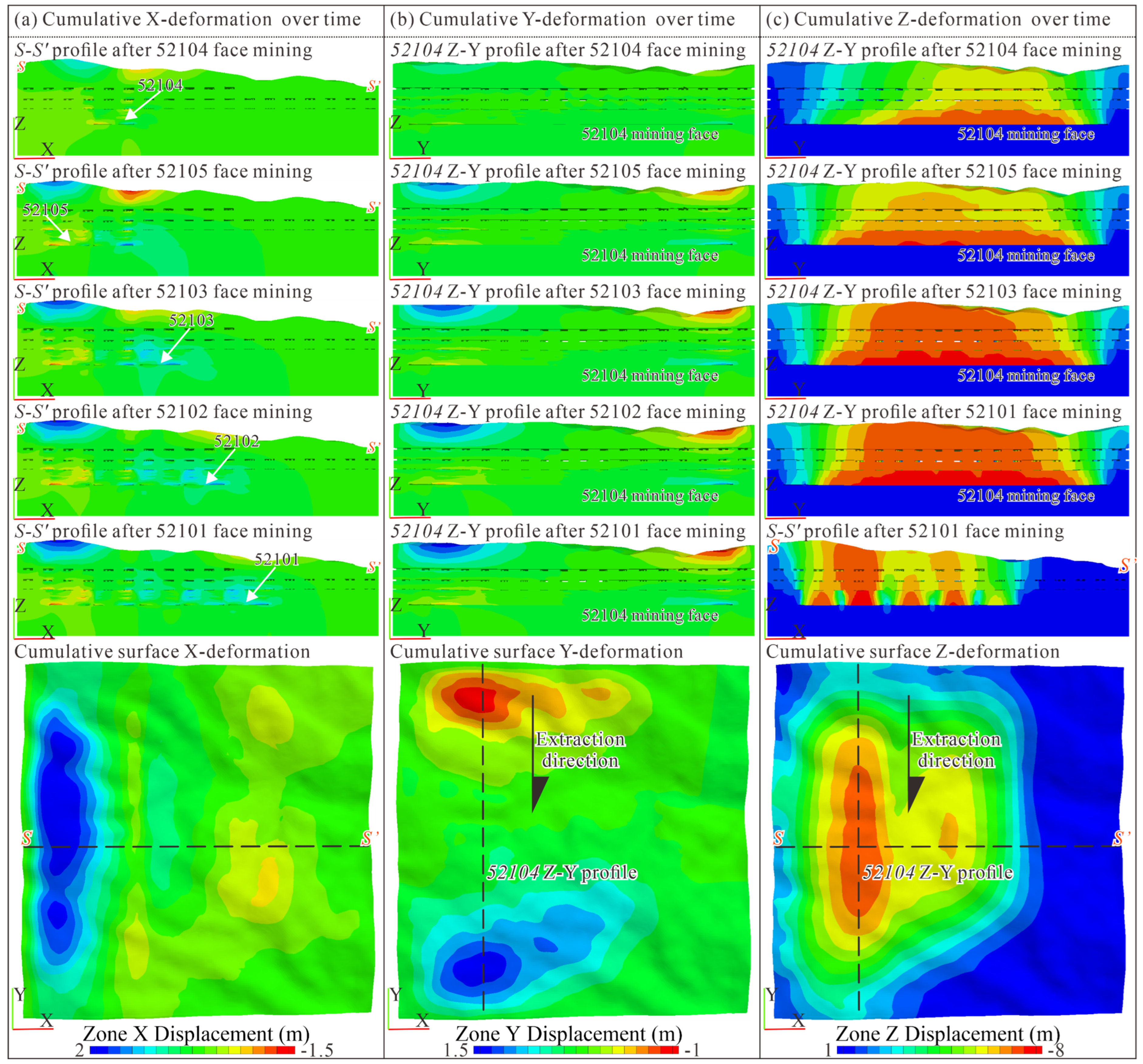

4.3. Simulated Underground Deformation

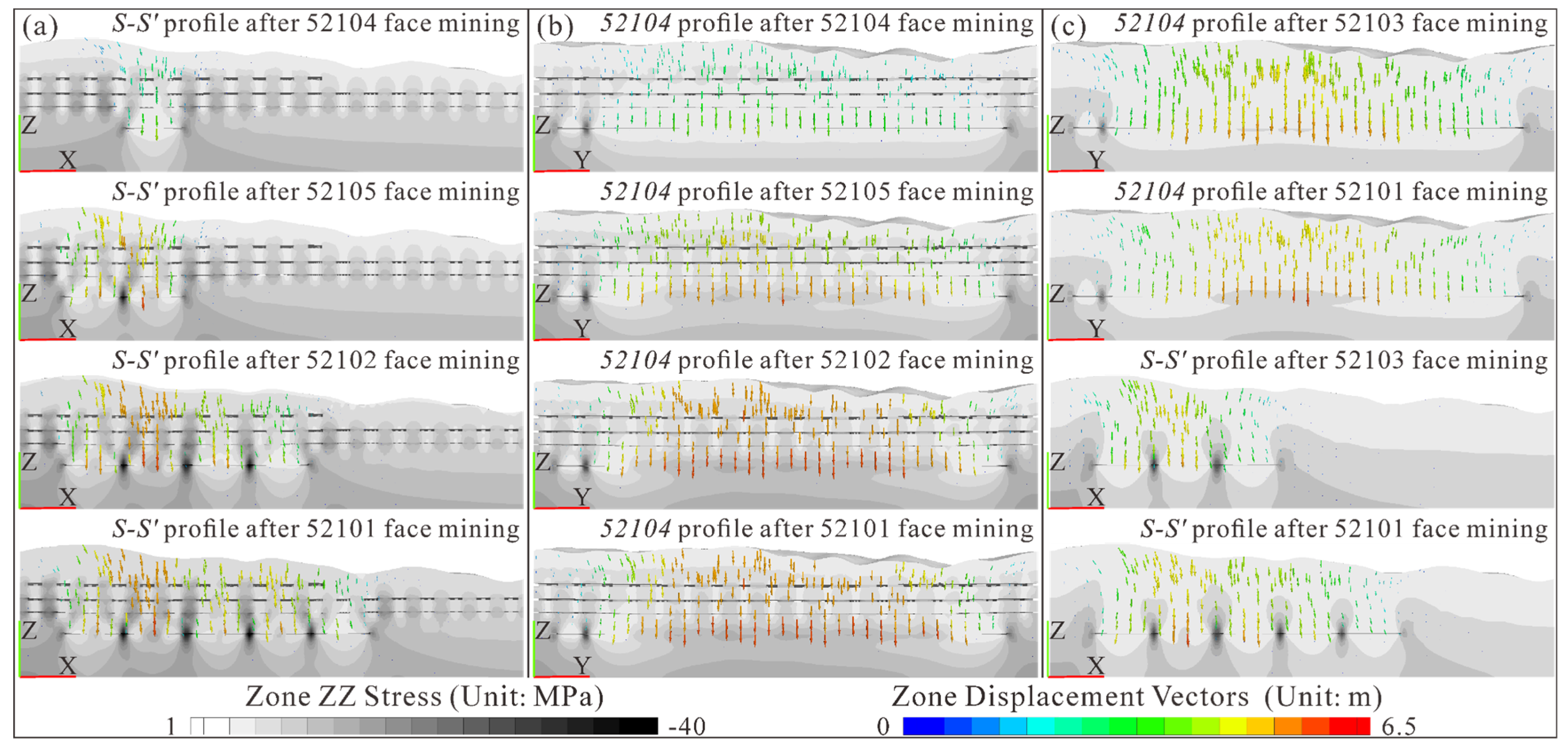

5. Discussion

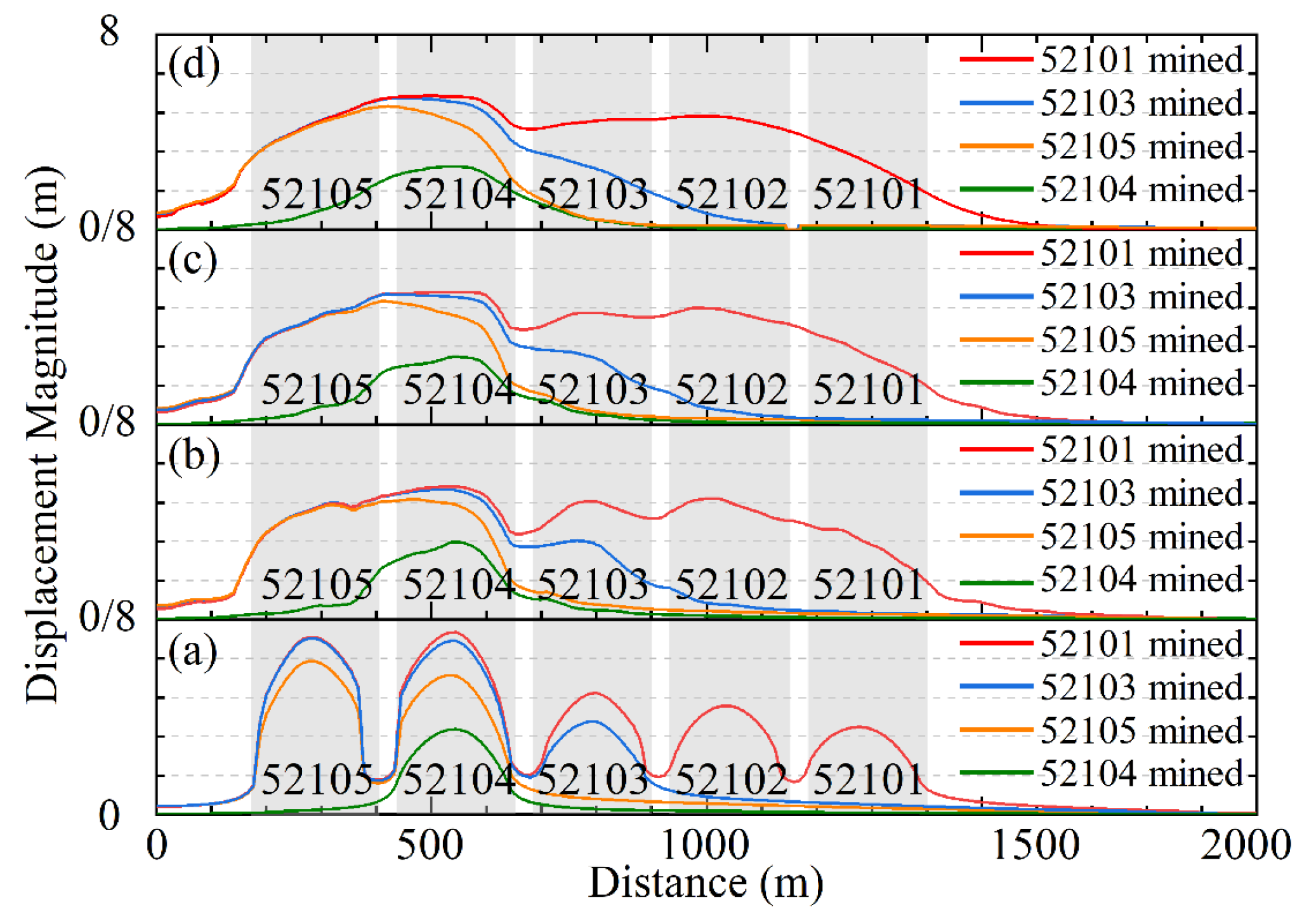

5.1. The Evolution Law of Ground Subsidence Induced by Multi-Seam Mining

5.2. Coal Pillar-Strata Interaction and Failure Mechanisms in Multi-Seam Mining

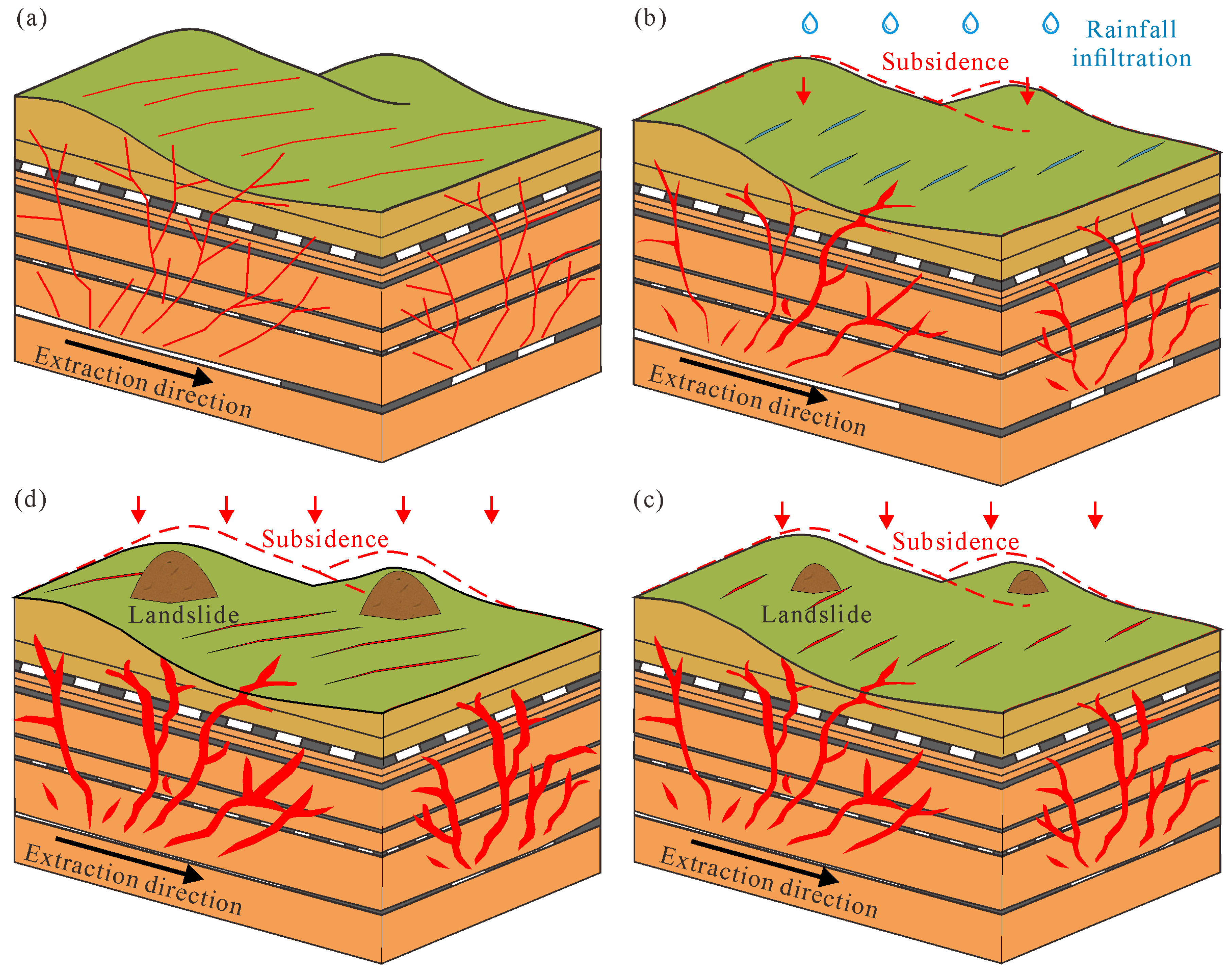

5.3. The Process and Interaction of Mining-Induced Hazard Chain

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Qi, L. The Current Situation and Prevention and Control Countermeasures for Typical Dynamic Disasters in Kilometer-Deep Mines in China. Saf. Sci. 2019, 115, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, E.F.; Nazem, M.; Karakus, M. The Effect of Rock Mass Gradual Deterioration on the Mechanism of Post-Mining Subsidence over Shallow Abandoned Coal Mines. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 91, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Qiu, H.; Ma, S.; Liu, Z.; Du, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, M. Slow Surface Subsidence and Its Impact on Shallow Loess Landslides in a Coal Mining Area. Catena 2022, 209, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Key World Energy Statistics 2020; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, F.G.; Stacey, T.R.; Genske, D.D. Mining Subsidence and Its Effect on the Environment: Some Differing Examples. Environ. Geol. 2000, 40, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergïnal, A.E.; Türkeş, M.; Ertek, T.A.; Baba, A.; Bayrakdar, C. Geomorphological Investigation of the Excavation-induced Dündar Landslide, Bursa—Turkey. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2008, 90, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modeste, G.; Doubre, C.; Masson, F. Time Evolution of Mining-Related Residual Subsidence Monitored over a 24-Year Period Using InSAR in Southern Alsace, France. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozzi, T.; Delaloye, R.; Poffet, D.; Hansmann, J.; Loew, S. Surface Subsidence and Uplift above a Headrace Tunnel in Metamorphic Basement Rocks of the Swiss Alps as Detected by Satellite SAR Interferometry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Chen, T.; Zhen, N.; Niu, R. Monitoring the Effects of Open-Pit Mining on the Eco-Environment Using a Moving Window-Based Remote Sensing Ecological Index. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 15716–15728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Pei, Y.; Qiao, W.; Wu, Y. Classification of the Type of Eco-Geological Environment of a Coal Mine District: A Case Study of an Ecologically Fragile Region in Western China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1513–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, K.; Hou, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J. Characteristics of Strata Movement and Method for Runoff Disaster Management for Shallow Multiseam Mining in Gully Regions: A Case Study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 172, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yang, T.; Liu, H.; Wei, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J. Characteristics of Stratum Movement Induced by Downward Longwall Mining Activities in Middle-Distance Multi-Seam. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 136, 104517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabraie, B.; Ren, G.; Smith, J.V. Characterising the Multi-Seam Subsidence Due to Varying Mining Configuration, Insights from Physical Modelling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 93, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Xu, J. Structural Characteristics of Key Strata and Strata Behaviour of a Fully Mechanized Longwall Face with 7.0 m Height Chocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2013, 58, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Qiu, H.; Yang, D.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, B.; Sun, K.; Cao, M. Surface Multi-Hazard Effect of Underground Coal Mining. Landslides 2023, 20, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, S.E.; Amponsah-Dacosta, F. A Review of Problems and Solutions of Abandoned Mines in South Africa. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2016, 30, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Kong, W.; Xiao, W.; Li, X.; Lian, X.; Hu, H. A Review of Monitoring, Calculation, and Simulation Methods for Ground Subsidence Induced by Coal Mining. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peternel, T.; Kumelj, Š.; Oštir, K.; Komac, M. Monitoring the Potoška Planina Landslide (NW Slovenia) Using UAV Photogrammetry and Tachymetric Measurements. Landslides 2017, 14, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L. Use of SAR/InSAR in Mining Deformation Monitoring, Parameter Inversion, and Forward Predictions: A Review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2020, 8, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Banerjee, B.P.; Raval, S. A Review of Laser Scanning for Geological and Geotechnical Applications in Underground Mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, W.; Hu, Z. A Review of UAV Monitoring in Mining Areas: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2019, 6, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jin, C.; Wang, Q.; Han, T.; Li, G.; Zhong, X.; Chen, G. Combining InSAR and Infrared Thermography with Numerical Simulation to Identify the Unstable Slope of Open-Pit: Qidashan Case Study, China. Landslides 2023, 20, 1961–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liu, G.; Deng, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, F. Large Deformation Monitoring over a Coal Mining Region Using Pixel-Tracking Method with High-Resolution Radarsat-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 7, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, P.R.; Davie, C.T.; Glendinning, S. Numerical Modelling of Shallow Abandoned Mine Working Subsidence Affecting Transport Infrastructure. Eng. Geol. 2013, 154, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Qiu, H.; Wang, L.; Pei, Y.; Tang, B.; Ma, S.; Yang, D.; Cao, M. Combining Rainfall-Induced Shallow Landslides and Subsequent Debris Flows for Hazard Chain Prediction. Catena 2022, 213, 106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.; Yadav, A.; Singh, G.S.P.; Sharma, S.K. Numerical Modeling Study of the Geo-Mechanical Response of Strata in Longwall Operations with Particular Reference to Indian Geo-Mining Conditions. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 1827–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, N.; Diederichs, M.S. Appropriate Uses and Practical Limitations of 2D Numerical Analysis of Tunnels and Tunnel Support Response. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2014, 32, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardino, P.; Fornaro, G.; Lanari, R.; Sansosti, E. A New Algorithm for Surface Deformation Monitoring Based on Small Baseline Differential SAR Interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Snoeij, P.; Geudtner, D.; Bibby, D.; Davidson, M.; Attema, E.; Potin, P.; Rommen, B.; Floury, N.; Brown, M.; et al. GMES Sentinel-1 Mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwell, D.T.; Price, E.J. Phase Gradient Approach to Stacking Interferograms. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 30183–30204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Choudhury, D.; Bhargava, K. Simulation of Rock Subjected to Underground Blast Using FLAC3D. JGS Spec. Publ. 2016, 2, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Peng, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, B. Improving Boundary Constraint of Probability Integral Method in SBAS-InSAR for Deformation Monitoring in Mining Areas. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, Q. Simulation Study on Spatial Form of the Suspended Roof Structure of Working Face in Shallow Coal Seam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhao, W.; Lu, Z.; Ren, J.; Miao, Y. Research on the Reasonable Width of the Waterproof Coal Pillar during the Mining of a Shallow Coal Seam Located Close to a Reservoir. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 3532784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, S.J.; Liu, T.Y.; Ma, F.S. Engineering Geology, Ground Surface Movement and Fissures Induced by Underground Mining in the Jinchuan Nickel Mine. Eng. Geol. 2004, 76, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wen, G.; Dai, L.; Sun, H.; Li, X. Ground Subsidence and Surface Cracks Evolution from Shallow-Buried Close-Distance Multi-Seam Mining: A Case Study in Bulianta Coal Mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 2835–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lin, B.; Qu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhai, C.; Jia, L.; Zhao, W. Stress Evolution with Time and Space during Mining of a Coal Seam. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2011, 48, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggan, J.; Gao, F.; Stead, D.; Elmo, D. Numerical Modelling of the Effects of Weak Immediate Roof Lithology on Coal Mine Roadway Stability. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 90–91, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Jia, J. Weakening Effects of Hydraulic Fracture in Hard Roof under the Influence of Stress Arch. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shimada, H.; Sasaoka, T.; Matsui, K.; Dou, L. Evolution and Effect of the Stress Concentration and Rock Failure in the Deep Multi-Seam Coal Mining. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhao, G.; Bai, E.; Guo, M.; Wang, Y. Effect of Overburden Bending Deformation and Alluvium Mechanical Parameters on Surface Subsidence Due to Longwall Mining. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 2751–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, B.; Xu, Y. Failure Propagation of Pillars and Roof in a Room and Pillar Mine Induced by Longwall Mining in the Lower Seam. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Siddle, H.; Reddish, D.; Whittaker, B. Landslides and Undermining: Slope Stability Interaction with Mining Subsidence Behaviour. In Proceedings of the 7th ISRM Congress, Aachen, Germany, 16–20 September 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marschalko, M.; Yilmaz, I.; Bednárik, M.; Kubečka, K. Influence of Underground Mining Activities on the Slope Deformation Genesis: Doubrava Vrchovec, Doubrava Ujala and Staric Case Studies from Czech Republic. Eng. Geol. 2012, 147–148, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschalko, M.; Matěj, F.; Lubomír, T. Influence of Mining Activity on Selected Landslide in the Ostrava-Karviná Coalfield. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2008, 13, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Urciuoli, G.; Picarelli, L.; Leroueil, S. Local Soil Failure before General Slope Failure. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2007, 25, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Song, Y.; Zhao, H.; Han, Z.; Wang, D. Changes of Precipitation Infiltration Recharge in the Circumstances of Coal Mining Subsidence in the Shen-Dong Coal Field, China. Acta Geol. Sin. (Eng.) 2012, 86, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasowski, J.; Bovenga, F. Investigating Landslides and Unstable Slopes with Satellite Multi Temporal Interferometry: Current Issues and Future Perspectives. Eng. Geol. 2014, 174, 103–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coal Seam | Thickness (m) | Coal Seam Structure | Interval (m) | Mineability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2−2 | 6.93~9.83 7.95 | Complex structure, typically containing 2–3 intercalations | - | Partially Mineable |

| 33.66~37.81 35.14 | ||||

| 3−1 | 1.74~2.87 2.64 | Simple structure, no intercalations or occasionally one | Mostly Mineable | |

| 37.30~45.27 40.74 | ||||

| 4−2 | 3.09~3.86 3.47 | Simple structure, containing one intercalation | Mostly Mineable | |

| 14.37~21.20 17.99 | ||||

| 4−3 | 0.94~1.55 1.23 | Simple structure, containing one intercalation | Mostly Mineable | |

| 13.09~16.29 14.44 | ||||

| 4−4 | 0.80~0.95 0.90 | Simple structure, containing one intercalation | Partially Mineable | |

| 34.44~41.79 37.94 | ||||

| 5−2 | 5.23~6.25 5.79 | Simple structure, locally containing 1–2 intercalations | Fully Mineable | |

| - |

| No. | Rock Stratum | Density ρ (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus E/Gpa | Poisson’s Ratio ν | Cohesion C/Mpa | Internal Friction Angle φ/◦ | Tensile Strength Rc/Mpa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loose layer | 1870 | 0.110 | 0.25 | 0.048 | 22.07 | _ |

| 2 | Clay | 1960 | 0.250 | 0.35 | 0.850 | 25.10 | 0.35 |

| 3 | CGS | 2560 | 7.070 | 0.15 | 3.040 | 33.00 | 4.34 |

| 4 | Coal Seams 2−2 | 1280 | 1.740 | 0.30 | 3.720 | 36.98 | 1.37 |

| 5 | FGS | 2450 | 0.803 | 0.21 | 2.540 | 38.13 | 1.87 |

| 6 | Coal Seams 3−1 | 1280 | 1.740 | 0.30 | 3.720 | 36.00 | 1.37 |

| 7 | Siltstone | 2470 | 0.826 | 0.19 | 3.130 | 39.29 | 1.75 |

| 8 | Coal Seams 4−2 | 1390 | 0.435 | 0.21 | 1.160 | 36.98 | 0.74 |

| 9 | Siltstone | 2320 | 0.824 | 0.23 | 2.420 | 38.60 | 1.24 |

| 10 | Coal Seams 4−3 | 1390 | 0.266 | 0.14 | 1.450 | 37.60 | 0.82 |

| 11 | FGS | 2430 | 1.112 | 0.17 | 2.640 | 39.37 | 1.24 |

| 12 | Coal Seams 4−4 | 1390 | 0.266 | 0.14 | 1.450 | 37.60 | 0.82 |

| 13 | Silty mudstone | 2150 | 1.021 | 0.22 | 3.660 | 38.69 | 0.65 |

| 14 | Coal Seams 5−2 | 1390 | 0.266 | 0.14 | 1.450 | 37.60 | 0.82 |

| 15 | CGS | 2690 | 5.610 | 0.29 | 3.500 | 33.00 | 3.70 |

| 16 | FGS | 2430 | 0.971 | 0.20 | 4.430 | 39.60 | 1.22 |

| Number | 5 November 2021–5 March 2022 | 5 March 2022–28 May 2022 | 5 November 2021–28 May 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | X | Y | Z | X | Y | Z | |

| MP1 | −19 | −8 | −2 | −16 | −6 | −31 | −35 | −14 | −33 |

| MP2 | 42 | −1 | −83 | −358 | 722 | −1314 | −316 | 721 | −1396 |

| MP3 | 8 | −2 | 96 | 386 | −208 | −107 | 394 | −210 | −12 |

| MP4 | 52 | −2 | 14 | −998 | 2262 | −2101 | −946 | 2260 | −2087 |

| MP5 | −569 | −596 | −4149 | −434 | −91 | −466 | −1003 | −687 | −4615 |

| MP6 | 16 | 4 | −15 | −124 | −165 | −149 | −108 | −161 | −164 |

| MP7 | −21 | −431 | −339 | −164 | −212 | −206 | −185 | −643 | −545 |

| MP8 | 19 | 20 | 129 | −77 | −100 | −196 | −58 | −80 | −67 |

| MP9 | −134 | 159 | −3253 | −2078 | 138 | −1941 | −2212 | 297 | −5194 |

| MP10 | −970 | 1913 | −2059 | −207 | −50 | −295 | −1177 | 1863 | −2354 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Guo, Z.; Wang, M.; Mei, J.; Liu, L.; Ashraf, T.; Wang, X. InSAR-Based Multi-Source Monitoring and Modeling of Multi-Seam Mining-Induced Deformation and Hazard Chain Evolution in the Loess Gully Region. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243993

Zhang Q, Guo Z, Wang M, Mei J, Liu L, Ashraf T, Wang X. InSAR-Based Multi-Source Monitoring and Modeling of Multi-Seam Mining-Induced Deformation and Hazard Chain Evolution in the Loess Gully Region. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243993

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qunjia, Zhenhua Guo, Meng Wang, Jiacheng Mei, Lei Liu, Tariq Ashraf, and Xue Wang. 2025. "InSAR-Based Multi-Source Monitoring and Modeling of Multi-Seam Mining-Induced Deformation and Hazard Chain Evolution in the Loess Gully Region" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243993

APA StyleZhang, Q., Guo, Z., Wang, M., Mei, J., Liu, L., Ashraf, T., & Wang, X. (2025). InSAR-Based Multi-Source Monitoring and Modeling of Multi-Seam Mining-Induced Deformation and Hazard Chain Evolution in the Loess Gully Region. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3993. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243993