Optimizing Cloud Mask Accuracy over Snow-Covered Terrain with a Multistage Decision Tree Framework

Highlights

- Optimized a multi-level decision tree cloud detection algorithm for cloud-snow discrimination.

- Utilized the distinct bright temperature difference at 3.7 μm and 11 μm to enhance cloud detection performance.

- Outperforms existing algorithms and significantly reduces the false cloud detection in snow-covered areas.

- Provides accurate and efficient cloud detection in the Northern Hemisphere to support related cryospheric studies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Preprocessing

2.1. AVHRR Surface Reflectance CDR

2.2. Landsat 5 Reference Snow and Cloud Maps

2.3. Ancillary Data

3. Methods

3.1. Selection of Truth Reference Samples

3.2. Build Training Dataset

3.3. Algorithm Improvement Based on Threshold Optimization

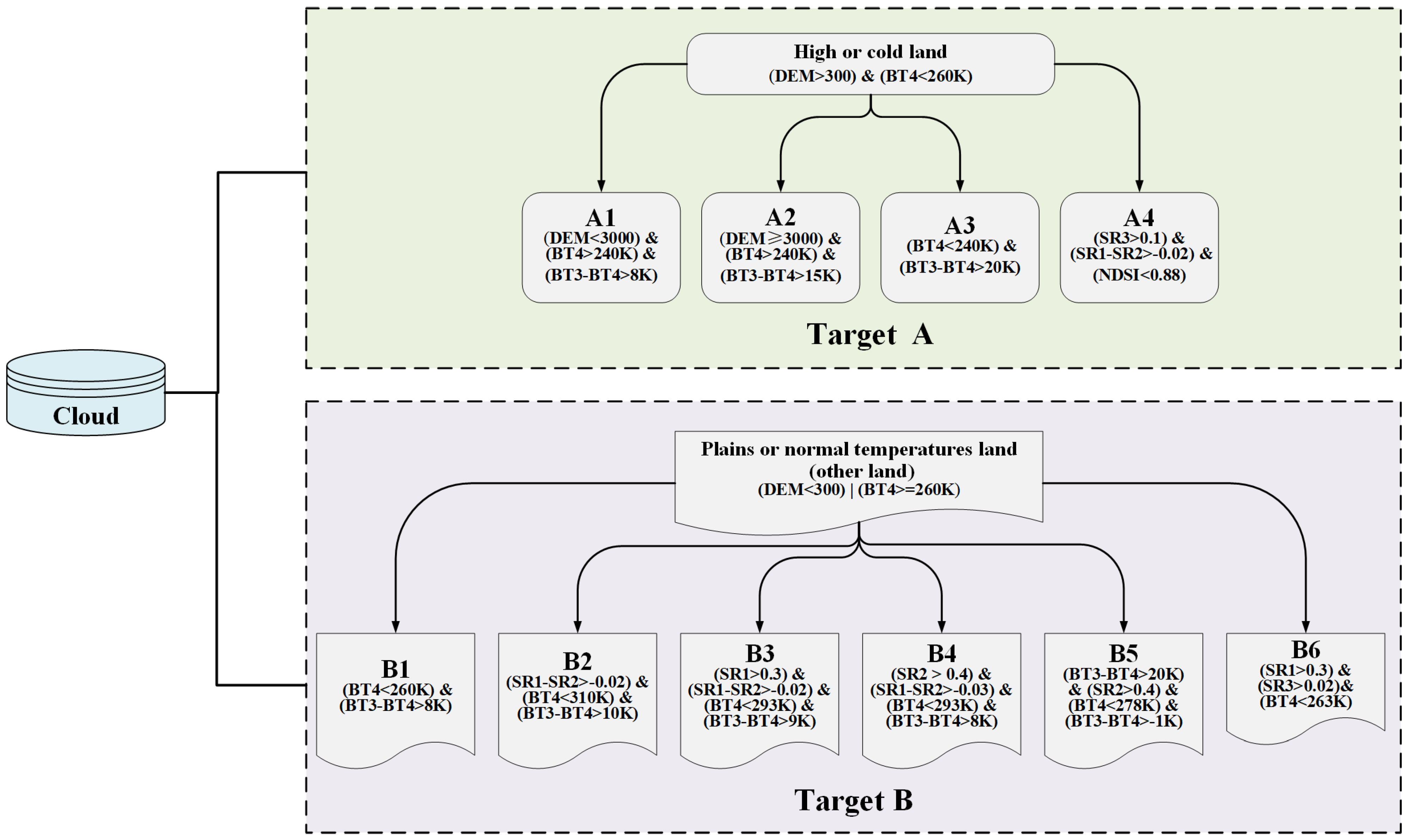

3.3.1. Existing Algorithm Framework

3.3.2. Proposed Algorithm Improvement Strategy

3.4. Accuracy Assessment Metrics

4. Results

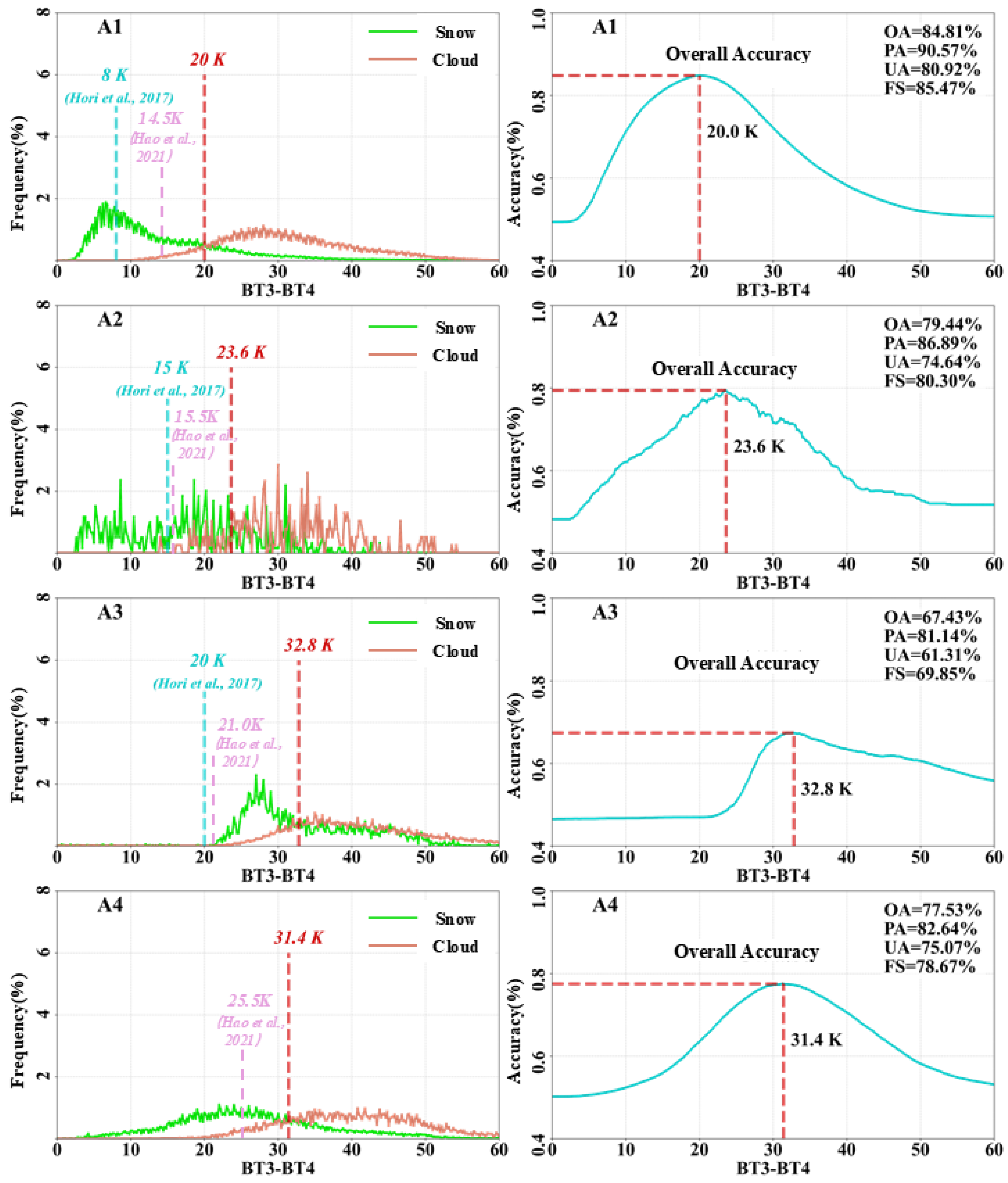

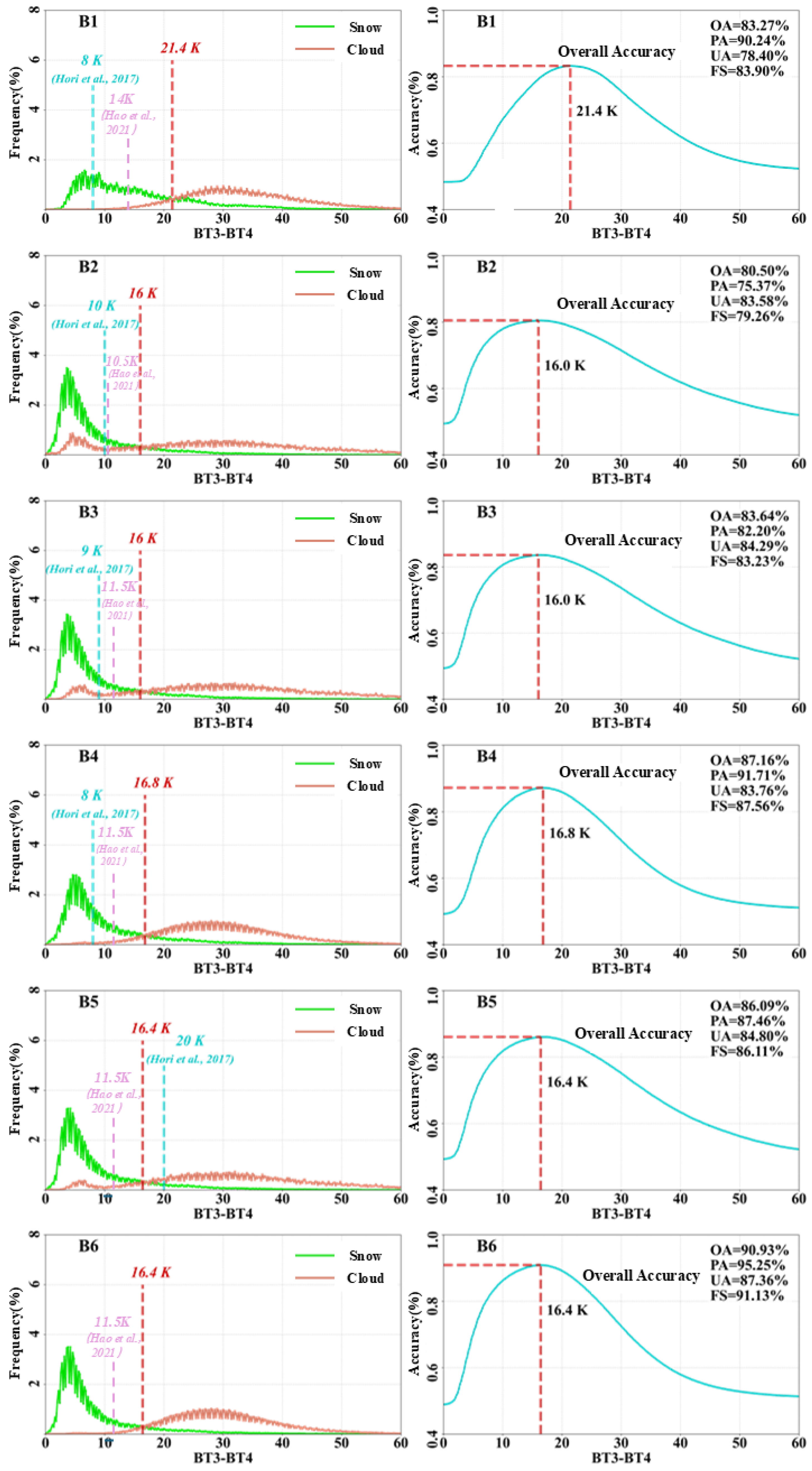

4.1. Improved Thresholds

4.2. Accuracy Assessment

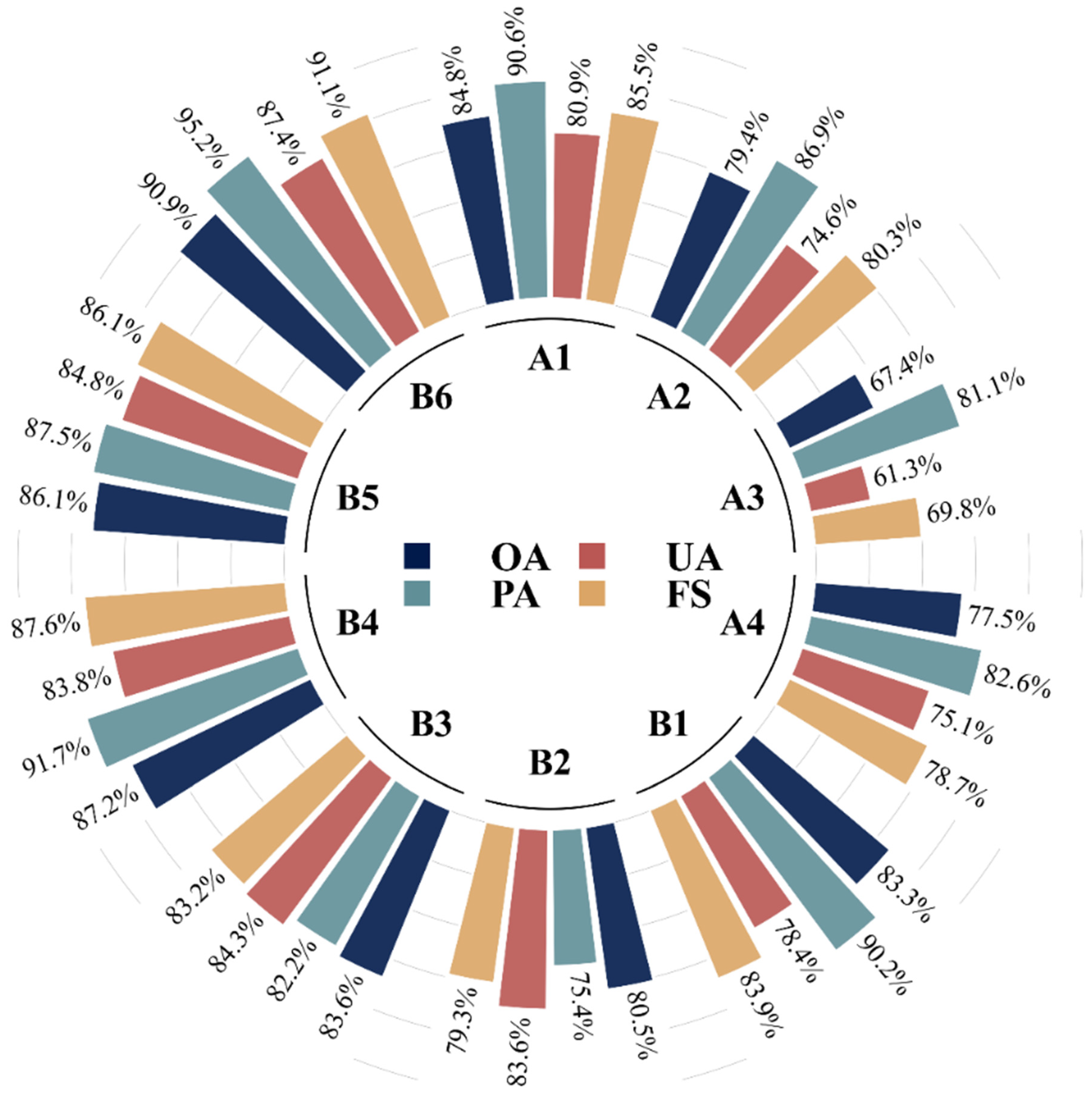

4.2.1. Overview of the Algorithm Accuracies

4.2.2. Algorithm Accuracies of Different Cloud Detection Schemes

4.3. Performance Comparison with Existing Algorithms

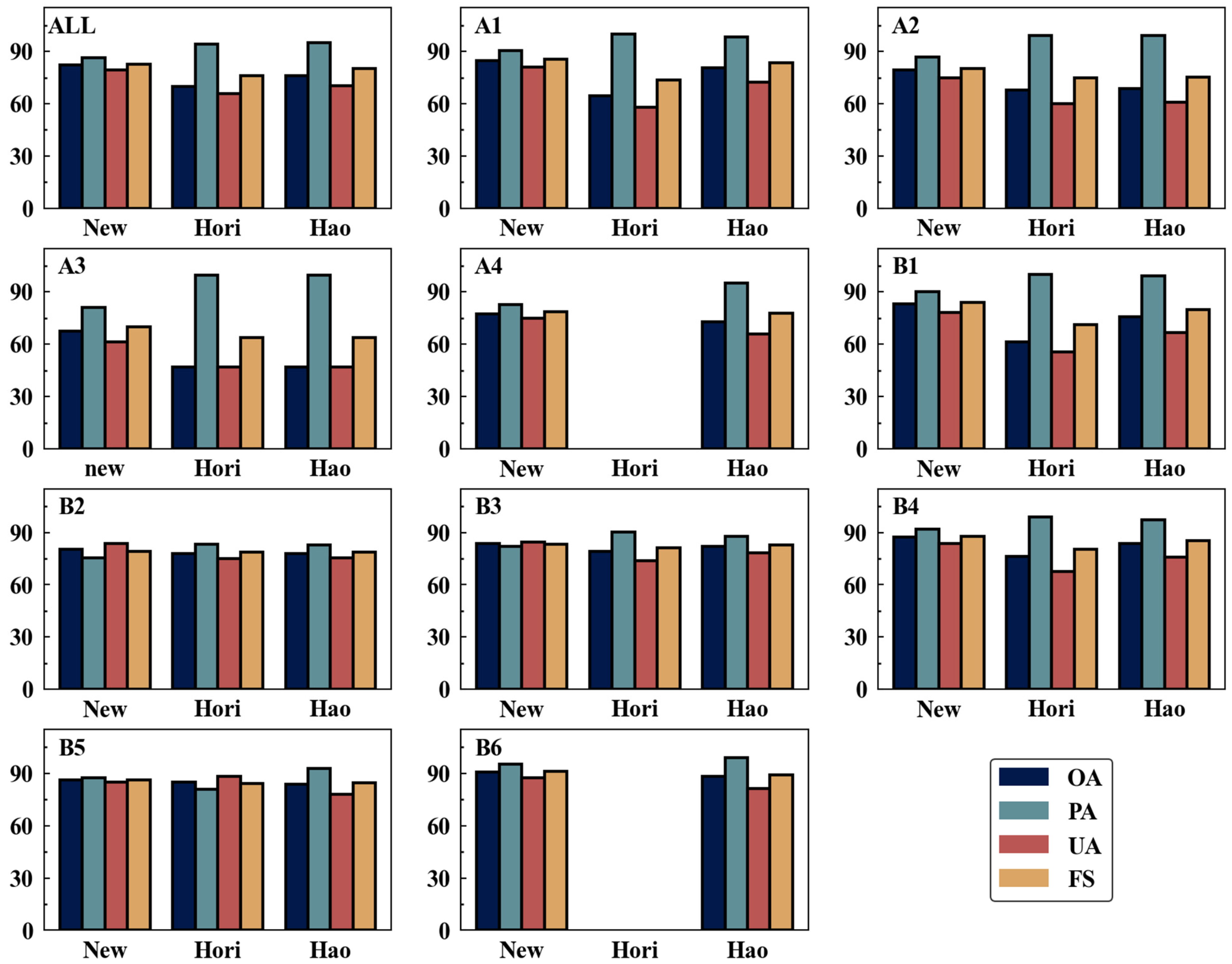

4.3.1. Overview of the Algorithm Performance Comparison

4.3.2. Algorithm Performance Comparison of Different Detection Schemes

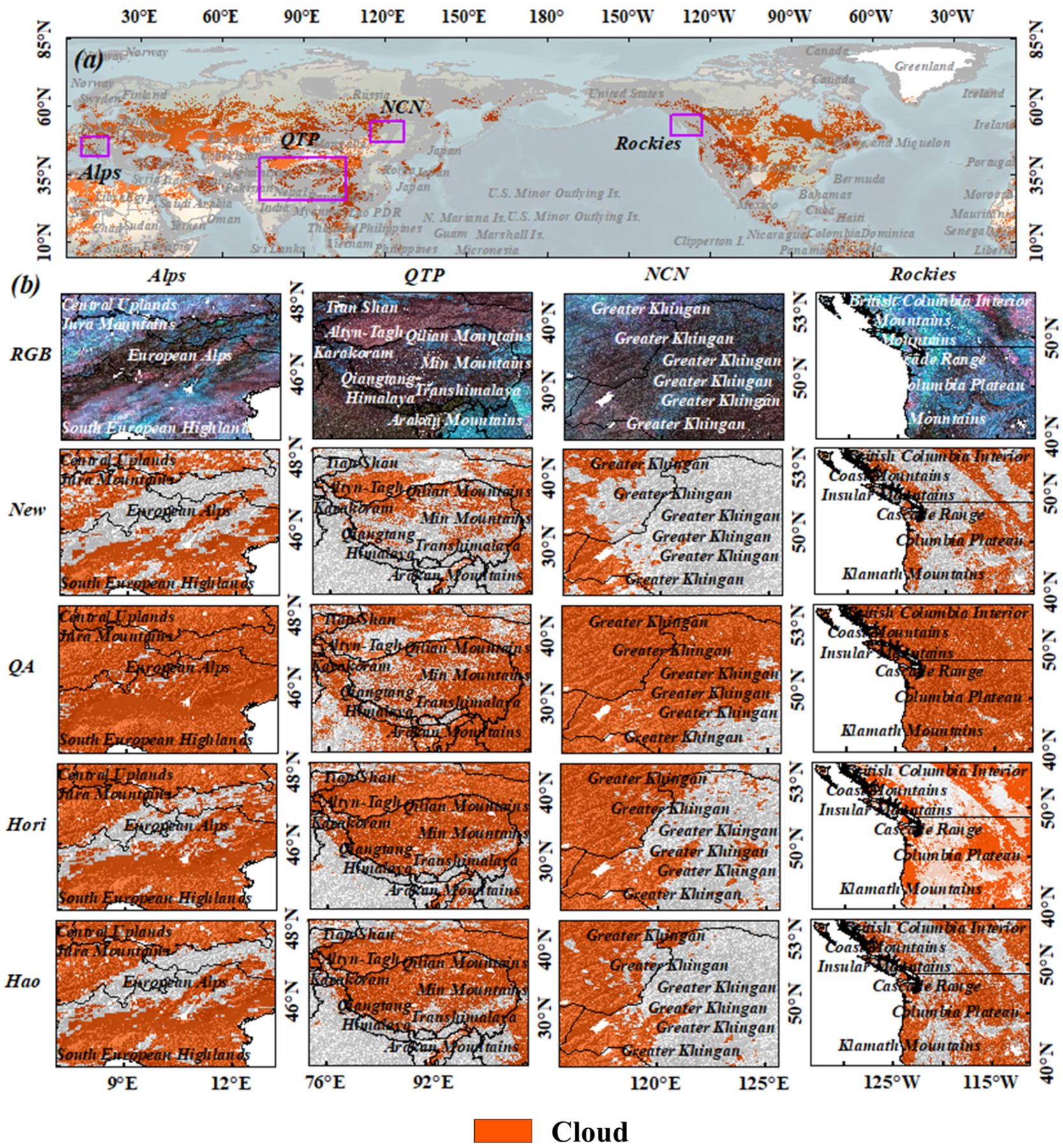

4.3.3. Algorithm Performance Comparison in Typical Regions

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Algorithm Uncertainty

5.1.1. Uncertainty of Truth Reference

5.1.2. Spectral Characteristic Overlap

5.1.3. Limitations of the Algorithm

5.2. Analysis of Application Prospects

5.2.1. Application and Characteristics of the Algorithm

5.2.2. Extended Applications of Products

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J.; Gong, P.; Fu, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Liang, S.; Xu, B.; Shi, J.; Dickinson, R. The role of satellite remote sensing in climate change studies. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Peng, Y.; Jia, K.; Hicks, B.J. Remote sensing big data for water environment monitoring: Current status, challenges, and future prospects. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, R.; Hubanks, P.A.; Platnick, S.; Meyer, K.; Holz, R.E.; Botambekov, D.; Wall, C.J. Updated observations of clouds by MODIS for global model assessment. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2483–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudente, V.H.R.; Martins, V.S.; Vieira, D.C.; de França e Silva, N.R.; Adami, M.; Sanches, I.D.A. Limitations of cloud cover for optical remote sensing of agricultural areas across South America. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2020, 20, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolin, A.W. Recent advances in remote sensing of seasonal snow. J. Glaciol. 2010, 56, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Deng, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Q.; Hao, X.; Liang, T. Spatiotemporal dynamics of snow cover based on multi-source remote sensing data in China. Cryosphere 2016, 10, 2453–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, T.; Suzuki, K.; Kawaguchi, S. Detection of clouds in Antarctica from infrared multispectral data of AVHRR. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 1987, 65, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, M.; Aoki, T.; Stamnes, K.; Chen, B.; Li, W. Preliminary validation of the GLI cryosphere algorithms with MODIS daytime data. Polar Meteorol. Glaciol. 2001, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, K.-G.; Stengel, M.; Meirink, J.F.; Riihelä, A.; Trentmann, J.; Akkermans, T.; Stein, D.; Devasthale, A.; Eliasson, S.; Johansson, E. CLARA-A3: The third edition of the AVHRR-based CM SAF climate data record on clouds, radiation and surface albedo covering the period 1979 to 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 4901–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, M.; Stapelberg, S.; Sus, O.; Schlundt, C.; Poulsen, C.; Thomas, G.; Christensen, M.; Carbajal Henken, C.; Preusker, R.; Fischer, J. Cloud property datasets retrieved from AVHRR, MODIS, AATSR and MERIS in the framework of the Cloud_cci project. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 881–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaps, A.; Lauer, A.; Kazeroni, R.; Stengel, M.; Eyring, V. Characterizing clouds with the CCClim dataset, a machine learning cloud class climatology. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3001–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.G.; Gan, T.Y. The Global Cryosphere: Past, Present, and Future; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Villaescusa Nadal, J.L. Development of a Global Long Term Surface Albedo Data Record from Noaa Avhrr for the Estimation of 38 Year Trends (1982–2020). Diploma Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Kuenzer, C.; Dietz, A.J.; Dech, S. The potential of Earth observation for the analysis of cold region land surface dynamics in europe—A review. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, G.; Agusti-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Beljaars, A.; Bidlot, J.; Blyth, E.; Bousserez, N.; Boussetta, S.; Brown, A.; et al. Satellite and In Situ Observations for Advancing Global Earth Surface Modelling: A Review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2038, Correction in Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 941.. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, M.; Sugiura, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Aoki, T.; Tanikawa, T.; Kuchiki, K.; Niwano, M.; Enomoto, H. A 38-year (1978–2015) Northern Hemisphere daily snow cover extent product derived using consistent objective criteria from satellite-borne optical sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 191, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Huang, G.; Che, T.; Ji, W.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, Q. The NIEER AVHRR snow cover extent product over China—A long-term daily snow record for regional climate research. Earth System Science Data 2021, 13, 4711–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E. NOAA CDR Program. (2019): NOAA Climate Data Record (CDR) of AVHRR Surface Reflectance, Version 5; NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information: Asheville, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Che, T.; Huang, X.; Hao, X.; Li, H. Snow cover mapping for complex mountainous forested environments based on a multi-index technique. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.C.M. AVHRR Surface Reflectance and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index—Climate Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document; CDRP-ATBD-0459 Rev. 2; NOAA Climate Data Record Program: Asheville, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N. Google Earth Engine. In EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts; American Geophysical Union: Vienna, Austria, 2013; Volume 15, p. 11997. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C.J.; Roy, D.P.; Arab, S.; Barnes, C.; Vermote, E.; Hulley, G.; Gerace, A.; Choate, M.; Engebretson, C.; Micijevic, E. The 50-year Landsat collection 2 archive. Sci. Remote Sens. 2023, 8, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foga, S.; Scaramuzza, P.L.; Guo, S.; Zhu, Z.; Dilley, R.D., Jr.; Beckmann, T.; Schmidt, G.L.; Dwyer, J.L.; Hughes, M.J.; Laue, B. Cloud detection algorithm comparison and validation for operational Landsat data products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 194, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Xie, P.; Wang, J.; Hao, X. A conditional probability interpolation method based on a space-time cube for modis snow cover products gap filling. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Jiang, L.; Wang, G.; Pan, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Cui, H.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, S. MODIS daily cloud-gap-filled fractional snow cover dataset of the Asian Water Tower region (2000–2022). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2501–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAAC, L. Global 30 Arc-Second Elevation Data Set GTOPO30; Land Process Distributed Active Archive Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, M.; DiMiceli, C.; Townshend, J.; Sohlberg, R.; Hubbard, A.; Wooten, M. MOD44W: Global MODIS water maps user guide. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2017, 10, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, S.A.; Strabala, K.I.; Menzel, W.P.; Frey, R.A.; Moeller, C.C.; Gumley, L.E. Discriminating clear sky from clouds with MODIS. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1998, 103, 32141–32157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamnes, K.; Li, W.; Eide, H.; Aoki, T.; Hori, M.; Storvold, R. ADEOS-II/GLI snow/ice products—Part I: Scientific basis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 111, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Pfeifroth, U. Remote sensing of solar surface radiation–a reflection of concepts, applications and input data based on experience with the effective cloud albedo. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 1537–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavolonis, M.J. Advances in extracting cloud composition information from spaceborne infrared radiances—A robust alternative to brightness temperatures. Part I: Theory. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 1992–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniston, M.; Diaz, H.; Bradley, R. Climatic change at high elevation sites: An overview. Clim. Change 1997, 36, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, C.D. Mountain Meteorology: Fundamentals and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Houze, R.A., Jr. Cloud Dynamics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Volume 104. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Q.; You, D.; Hao, D.; Wu, S.; Lin, X. Characterizing land surface anisotropic reflectance over rugged terrain: A review of concepts and recent developments. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xiao, Z. Exploring topographic effects on surface parameters over rugged terrains at various spatial scales. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, L.; Yang, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Yang, K.; Xu, X.; Liu, L. Land-surface processes and summer-cloud-precipitation characteristics in the Tibetan Plateau and their effects on downstream weather: A review and perspective. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Woodcock, C.E. Automated cloud, cloud shadow, and snow detection in multitemporal Landsat data: An algorithm designed specifically for monitoring land cover change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 152, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillinger, T.; Roberts, D.A.; Collar, N.M.; Dozier, J. Cloud masking for Landsat 8 and MODIS Terra over snow-covered terrain: Error analysis and spectral similarity between snow and cloud. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 6169–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.D.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Menzel, W.P.; Tanre, D. Remote sensing of cloud, aerosol, and water vapor properties from the moderate resolution imaging spectrometer (MODIS). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, A.; Zhang, N.; Liang, Y. A Machine Learning Algorithm Using Texture Features for Nighttime Cloud Detection from FY-3D MERSI L1 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Hao, X.; Che, T.; Shao, D.; Ji, W.; Luo, S.; Huang, G.; Feng, T.; Dong, L.; Sun, X. Estimating AVHRR snow cover fraction by coupling physical constraints into a deep learning framework. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Huang, G.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, X.; Ji, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X. Development and validation of a new MODIS snow-cover-extent product over China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 1937–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Shen, H.; Guan, X.; Chen, J.M.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Long time-series NDVI reconstruction in cloud-prone regions via spatio-temporal tensor completion. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 264, 112632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Park, T.; Yan, G.; Liu, Z.; Yang, B.; Chen, C.; Nemani, R.R.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Myneni, R.B. Evaluation of MODIS LAI/FPAR product collection 6. Part 2: Validation and intercomparison. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, G. Estimation of soil moisture from optical and thermal remote sensing: A review. Sensors 2016, 16, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doraiswamy, P.C.; Moulin, S.; Cook, P.W.; Stern, A. Crop yield assessment from remote sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Yin, Z.; Zeng, C.; Duan, S.-B.; Göttsche, F.-M.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Shen, H. Spatially continuous and high-resolution land surface temperature product generation: A review of reconstruction and spatiotemporal fusion techniques. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2021, 9, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Band Name | Units | Scale | Wavelength | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR1 | 0.0001 | 640 nm | Bidirectional surface reflectance | |

| SR2 | 0.0001 | 860 nm | Bidirectional surface reflectance | |

| SR3 | 0.0001 | 3.75 um | Bidirectional surface reflectance | |

| BT3 | K | 0.1 | 3.75 um | Brightness temperature |

| BT4 | K | 0.1 | 11.0 um | Brightness temperature |

| BT5 | K | 0.1 | 12.0 um | Brightness temperature |

| RAA | deg | 0.01 | Relative sensor azimuth angle | |

| SZA | deg | 0.01 | Solar zenith angle | |

| VZA | deg | 0.01 | View zenith angle, scale 0.01 | |

| QA | Quality control bit flags |

| Bitmask Value | Description | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bit 0 | Unused | No | Yes |

| Bit 1 | Pixel is cloudy | No | Yes |

| Bit 2 | Pixel contains cloud shadow | No | Yes |

| Bit 3 | Pixel is over water | No | Yes |

| Bit 4 | Pixel is over sunglint | No | Yes |

| Bit 5 | Pixel is over dense dark vegetation | No | Yes |

| Bit 6 | Pixel is at night (high solar zenith) | No | Yes |

| Bit 7 | Channels 1–5 are valid | No | Yes |

| Bit 8 | Channel 1 value is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 9 | Channel 2 value is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 10 | Channel 3 value is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 11 | Channel 4 value is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 12 | Channel 5 value is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 13 | RHO3 value is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 14 | BRDF correction is invalid | No | Yes |

| Bit 15 | Polar flag, latitude over 60 degrees (land) or 50 degrees (ocean) | No | Yes |

| Name | Units | Scale | Wavelength (μm) | Spatial Resolution | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR_B1 | 2.75 × 10−5 | 0.45~0.52 | 30 m | Band 1 (blue) surface reflectance | |

| SR_B2 | 2.75 × 10−5 | 0.52~0.60 | 30 m | Band 2 (green) surface reflectance | |

| SR_B3 | 2.75 × 10−5 | 0.63~0.69 | 30 m | Band 3 (red) surface reflectance | |

| SR_B4 | 2.75 × 10−5 | 0.77~0.90 | 30 m | Band 4 (near-infrared) surface reflectance | |

| SR_B5 | 2.75 × 10−5 | 1.55~1.75 | 30 m | Band 5 (shortwave infrared 1) surface reflectance | |

| ST_B6 | K | 3.418 × 10−3 | 10.40~12.50 | 120 m | Band 6 surface temperature. |

| SR_B7 | 2.75 × 10−5 | 2.08~2.35 | 30 m | Band 7 (shortwave infrared 2) surface reflectance | |

| QA_PIXEL | Pixel quality attributes generated from the CFMASK algorithm |

| Bitmask Value | Description | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bit 0 | Fill | |||

| Bit 1 | Dilated Cloud | |||

| Bit 2 | Unused | |||

| Bit 3 | Cloud | |||

| Bit 4 | Cloud Shadow | |||

| Bit 5 | Snow | |||

| Bit 6 | Clear | Cloud or Dilated Cloud bits are set | Cloud and Dilated Cloud bits are not set | |

| Bit 7 | Water | |||

| Bit 8–9 | Cloud Confidence | None | Low | Medium |

| Bit 10–11 | Cloud Shadow Confidence | None | Low | Medium |

| Bit 12–13 | Snow/Ice Confidence | None | Low | Medium |

| Bit 14–15 | Cirrus Confidence | None | Low | Medium |

| Classification | Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface reflectance data (SR) | SR1 | SR2 | SR3 | |

| Bright temperature data (BT) | BT4 | |||

| Index and band combination data (I&B) | NDVI | SR1-SR2 | BT3-BT4 | BT4-BT5 |

| Terrain data (TD) | DEM | |||

| Confusion Matrix | Prediction/Product | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Positive | Negative | |

| Positive | TP | FN | |

| Negative | FP | TN | |

| Target | Target Serial Number | Switch | Elevation (m) | SR1 | SR2 | SR3 | SR1-SR2 | NDVI | BT4 | BT3-BT4 | BT4-BT5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: high or cold land (DEM > 300 and BT4 < 260 K) | A1 | On | <3000 | ≥240 | >20 | ||||||

| A2 | On | ≥3000 | ≥240 | >23.6 | |||||||

| A3 | On | <240 | >32.8 | ||||||||

| A4 | On | >0.1 | >0.02 | >31.4 | |||||||

| B: plains or normal-temperature land (other land) (DEM < 300 and BT4 ≥ 260 K) | B1 | On | <260 | >21.4 | |||||||

| B2 | On | >−0.02 | <310 | >16 | |||||||

| B3 | On | >0.3 | >−0.02 | <293 | >16 | ||||||

| B4 | On | >0.4 | >−0.03 | <293 | >16.8 | >−1 | |||||

| B5 | On | >0.4 | <278 | >16.4 | >−1 | ||||||

| B6 | On | >0.3 | >0.02 | >16.4 | |||||||

| B7 | Off | >0.5 | >288 | ||||||||

| B8 | Off | >310 | |||||||||

| B9 | Off | >1000 | <0.4 | <−0.04 | >275 | ||||||

| B10 | Off | <−0.04 | >300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Q.; Hao, X.; Shao, D.; Ji, W.; Huang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J. Optimizing Cloud Mask Accuracy over Snow-Covered Terrain with a Multistage Decision Tree Framework. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243992

Zhao Q, Hao X, Shao D, Ji W, Huang G, Zhao Z, Zhang J. Optimizing Cloud Mask Accuracy over Snow-Covered Terrain with a Multistage Decision Tree Framework. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243992

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Qin, Xiaohua Hao, Donghang Shao, Wenzheng Ji, Guanghui Huang, Zisheng Zhao, and Juan Zhang. 2025. "Optimizing Cloud Mask Accuracy over Snow-Covered Terrain with a Multistage Decision Tree Framework" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243992

APA StyleZhao, Q., Hao, X., Shao, D., Ji, W., Huang, G., Zhao, Z., & Zhang, J. (2025). Optimizing Cloud Mask Accuracy over Snow-Covered Terrain with a Multistage Decision Tree Framework. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3992. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243992