Precipitation Microphysics Evolution of Typhoon During the Sharp Turn: A Case Study of Vongfong (2014)

Highlights

- During the sudden turn of Super Typhoon Vongfong (2014), the precipitation structure also changed accordingly: the precipitation coverage expanded, convective rainfall weakened, and stratiform rainfall intensified.

- The intensification of stratiform precipitation was associated with enhanced warm-rain processes due to increased cloud liquid water, whereas the weakening of convective precipitation was related to weakened ice-phase processes due to decreased cloud ice content.

- This study analyzes the evolution of precipitation during the base observation of the sudden turn of the typhoon, which can provide valuable guidance for improving flood-risk assessment, optimizing urban drainage, and emergency response planning.

- The findings provided observational constraints to improve the representation of cloud microphysics parameterization in typhoon prediction models and also contributed to the development of more accurate precipitation nowcasting and typhoon intensity–structure prediction tools.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. GPM DPR

2.2. Typhoon Track Data

2.3. PEI

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Typhoon Vongfong

3.2. The Precipitation Characteristics of Typhoon Vongfong

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The sudden turn of Super Typhoon Vongfong (2014) occurred during the eastward retreat of the WPSH. Before the sharp turn, the typhoon reached its peak intensity with the lowest central pressure and the highest wind speed. Its structure was highly organized with strong and concentrated upward motion within the eyewall. During the sharp turn, the typhoon weakened, the upward motion in the eyewall decreased, and the TC structure became more dispersed.

- The spatial distribution and intensity of precipitation changed significantly during the sudden turn of a typhoon. Before the sharp turn, convective precipitation was concentrated in the eyewall, with an average rate of 19.26 mm h−1. During the sudden change in moving direction, the precipitation area expanded, and the distribution of convective precipitation changed from the inner eyewall to the outer eyewall and spiral rainbands, with the average rate decreasing to 15.52 mm h−1. In contrast, stratiform precipitation increased from 4.37 mm h−1 to 7.70 mm h−1 during this period.

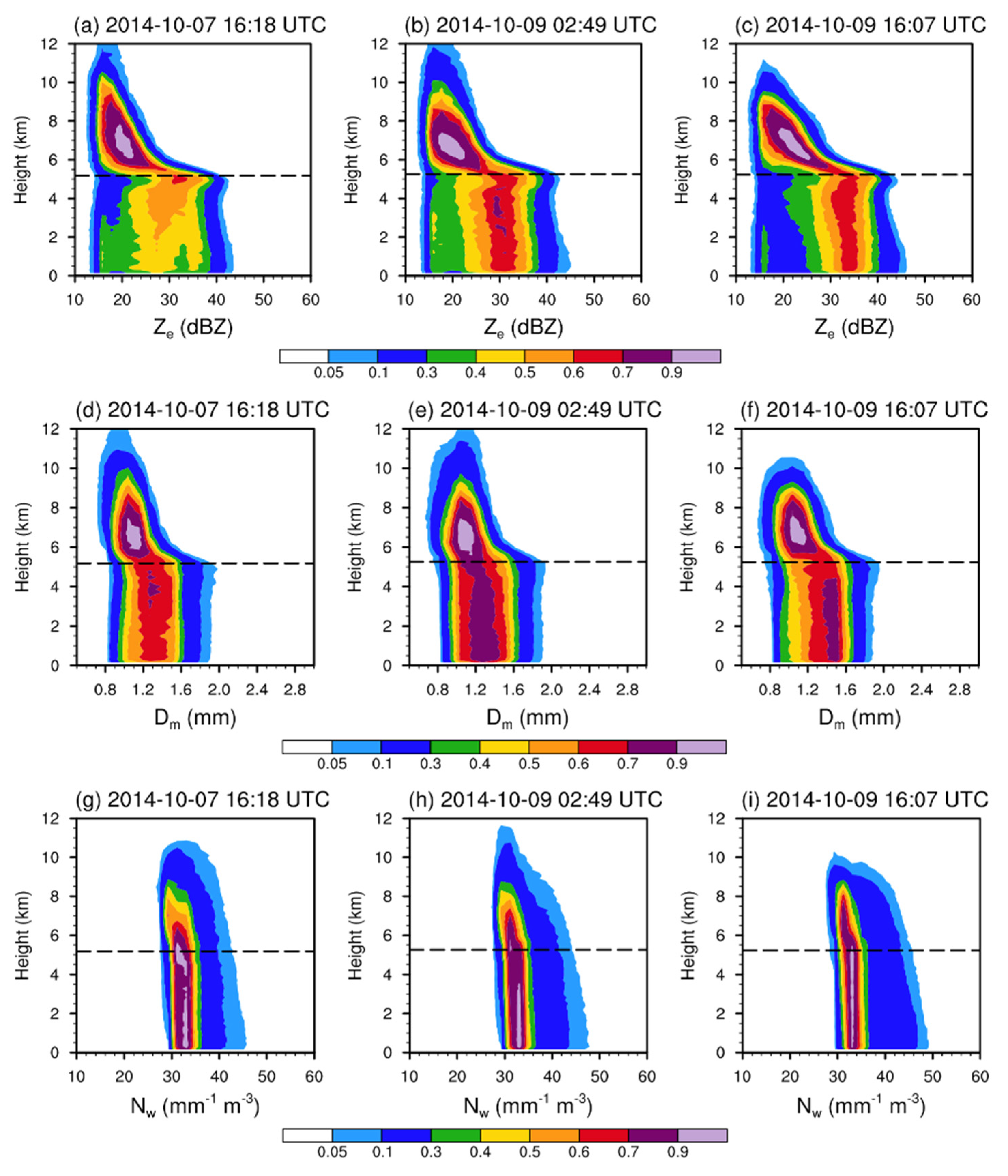

- During the sharp turn, the vertical structure of precipitation and hydrometeor content underwent significant changes influenced by the weakening of the typhoon. Due to convective precipitation mainly developed around the eyewall, the weakened eyewall ascent reduced the height of convection precipitation, with the cloud-top height decreasing from 12 km to 11 km, accompanied by lower ice water content and weaker ice-phase processes, which led to a decrease in convective precipitation intensity. Stratiform precipitation mainly occurred outside the eyewall. The increased southwest moisture transport increased cloud water content (LWP), enhancing the occurrence probabilities of large raindrops and strengthening stratiform rainfall.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emanuel, K. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature 2005, 436, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, R.; Heft-Neal, S.; Chavas, D.R.; Griswold, M.; Wang, Z.; Clark-Ginsberg, A.; Guha-Sapir, D.; Bendavid, E.; Wagner, Z. Global population profile of tropical cyclone exposure from 2002 to 2019. Nature 2024, 626, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archambault, H.M.; Bosart, L.F.; Keyser, D.; Cordeira, J.M. A Climatological Analysis of the Extratropical Flow Response to Recurving Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclones. Mon. Weather Rev. 2013, 141, 2325–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Heming, J.; Torn, R.D.; Lai, S.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. Unusual tracks: Statistical, controlling factors and model prediction. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 2023, 12, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heming, J.T.; Prates, F.; Bender, M.A.; Bowyer, R.; Cangialosi, J.; Caroff, P.; Coleman, T.; Doyle, J.D.; Dube, A.; Faure, G.; et al. Review of Recent Progress in Tropical Cyclone Track Forecasting and Expression of Uncertainties. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 2019, 8, 181–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, G.; Zhou, C.; Wong, W.K.; Yang, M.; Xu, Y.; Chen, P.; Wan, R.; Hu, X. Are We Reaching the Limit of Tropical Cyclone Track Predictability in the Western North Pacific? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E410–E428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Weather Channel. Super Typhoon Vongfong Becomes Strongest Storm on Earth. 2014. Available online: https://weather.com/storms/hurricane/news/vongfong-satellite-images-strongest-storm-20141010 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Vinour, L.; Jullien, S.; Mouche, A.; Combot, C.; Mangeas, M. Observations of Tropical Cyclone Inner-Core Fine-Scale Structure, and Its Link to Intensity Variations. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 78, 3651–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L. Characterizing the Macro and Micro Properties of Precipitation During the Landfall of Typhoon Lekima by Using GPM Observations. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbach, H.M.; Bousquet, O.; Bucci, L.; Chang, P.; Cione, J.; Ditchek, S.; Doyle, J.; Duvel, J.-P.; Elston, J.; Goni, G.; et al. Recent advancements in aircraft and in situ observations of tropical cyclones. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 2023, 12, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tian, R.; Lyu, X.; Ling, Z.; Sun, J.; Cao, A. Annual Review of In Situ Observations of Tropical Cyclone–Ocean Interaction in the Western North Pacific During 2023. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-J.; Yang, S.-C.; Chen, S.S. Improving Analysis and Prediction of Tropical Cyclones by Assimilating Radar and GNSS-R Wind Observations: Ensemble Data Assimilation and Observing System Simulation Experiments Using a Coupled Atmosphere–Ocean Model. Weather Forecast. 2022, 37, 1533–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, F. Precipitation microphysics of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific based on GPM DPR observations: A preliminary analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 3124–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, W. Precipitation microphysics of locally-originated typhoons in the south China sea based on GPM satellite observations. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lei, H.; Zheng, H. Precipitation characteristics of typhoon Lekima (2019) at landfall revealed by joint observations from GPM satellite and S-band radar. Atmos. Res. 2021, 260, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.Y.; Kakar, R.K.; Neeck, S.; Azarbarzin, A.A.; Kummerow, C.D.; Kojima, M.; Oki, R.; Nakamura, K.; Iguchi, T. The Global Precipitation Measurement Mission. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 95, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skofronick-Jackson, G.; Petersen, W.A.; Berg, W.; Kidd, C.; Stocker, E.F.; Kirschbaum, D.B.; Kakar, R.; Braun, S.A.; Huffman, G.J.; Iguchi, T.; et al. The Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission for science and society. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 1679–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skofronick-Jackson, G.; Kirschbaum, D.; Petersen, W.; Huffman, G.; Kidd, C.; Stocker, E.; Kakar, R. The Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission’s scientific achievements and societal contributions: Reviewing four years of advanced rain and snow observations. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 144, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, T.; Seto, S.; Meneghini, R.; Yoshida, N.; Awaka, J.; Le, M.; Chandrasekar, V.; Brodzik, S.; Kubota, T. GPM/DPR Level-2 Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 2010. Available online: https://gpm.nasa.gov/resources/documents/gpm-dpr-level-2-algorithm-theoretical-basis-document-atbd (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Yang, B.; Ren, S.; Wang, X.; Niu, N. Precipitation Characteristics at Different Developmental Stages of the Tibetan Plateau Vortex in July 2021 Based on GPM-DPR Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ye, G.; Leung, J.C.-H.; Zhang, B. Microphysical Characteristics of Summer Precipitation over the Taklamakan Desert Based on GPM-DPR Data from 2014 to 2023. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Yong, B.; Gourley, J.J. Monitoring the super typhoon Lekima by GPM-based near-real-time satellite precipitation estimates. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Xie, J. Revisiting the Characteristics of Super Typhoon Saola (2023) Using GPM, Himawari-9 and FY-4B Satellite Data. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Das, S.K.; Deshpande, S.M.; Deshpande, M.; Pandithurai, G. Regional variability of precipitation characteristics in tropical cyclones over the North Indian Ocean from GPM-DPR measurements. Atmos. Res. 2023, 283, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sunilkumar, K.; Srivastava, M.K. Microphysical Characteristics of Cyclonic Rainfall: A GPM-DPR Based Study Over the Arabian Sea. Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10, e2023EA002895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, F.; Ralph, F.M.; Wilson, A.M.; Lettenmaier, D.P. GPM satellite radar measurements of precipitation and freezing level in atmospheric rivers: Comparison with ground-based radars and reanalyses. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 12747–12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ryu, J.; Lee, S.; Sohn, B. Characteristics of global light rain system from GPM/DPR measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, K.R.; Kruk, M.C.; Levinson, D.H.; Diamond, H.J.; Neumann, C.J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahtan, J.; Knapp, R.; Schreck, C.J.; Diamond, H.J.; Kossin, J.P.; Kruk, M.C. International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) Project, Version 4r01. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. 2024. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ncdc:C01552 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wu, L.; Zong, H.; Liang, J. Observational Analysis of Sudden Tropical Cyclone Track Changes in the Vicinity of the East China Sea. J. Atmos. Sci. 2011, 68, 3012–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Fei, J.; Huang, X.; Cheng, X.; Ding, J.; He, Y. A numerical study on the combined effect of midlatitude and low-latitude systems on the abrupt track deflection of Typhoon Megi (2010). Mon. Weather. Rev. 2014, 142, 2483–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cha, D.; Lee, M.K.; Moon, J.; Hahm, S.; Noh, K.; Chan, J.C.L.; Bell, M. Impact of cloud microphysics schemes on tropical cyclone forecast over the western North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD032288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, D.S.; Fischer, M.S.; O’Neill, M.E. Reconsideration of the Mass and Condensate Sources for the Tropical Cyclone Outflow. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 106, E1342–E1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, D. Impacts of cloud radiative processes on the convective and stratiform rainfall associated with Typhoon Fitow (2013). Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 16, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 7 October 2014 16:18 | 9 October 2014 02:49 | 9 October 2014 16:07 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rain Types | Stratiform | Convective | Stratiform | Convective | Stratiform | Convective |

| No. of samples | 5023 | 782 | 4834 | 1365 | 5610 | 1469 |

| Rain rate (mm/h) | 4.37 | 19.26 | 5.03 | 17.17 | 7.70 | 15.52 |

| LWP (g m−2) | 960.54 | 3532.39 | 1090.47 | 3028.29 | 1608.73 | 2768.58 |

| IWP (g m−2) | 421.46 | 492.31 | 379.63 | 307.47 | 535.70 | 256.01 |

| PEI (h−1) | 2.53 | 4.46 | 2.87 | 5.07 | 2.95 | 5.26 |

| Dm (mm) | 1.32 | 1.46 | 1.33 | 1.38 | 1.35 | 1.40 |

| Nw (mm−1m−3) | 34.28 | 36.53 | 34.94 | 37.57 | 36.27 | 37.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, G.; Zhang, W.; Leung, J.C.-H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Dong, W. Precipitation Microphysics Evolution of Typhoon During the Sharp Turn: A Case Study of Vongfong (2014). Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243984

Ye G, Zhang W, Leung JC-H, Wang F, Zhang B, Dong W. Precipitation Microphysics Evolution of Typhoon During the Sharp Turn: A Case Study of Vongfong (2014). Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243984

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Guiling, Wentao Zhang, Jeremy Cheuk-Hin Leung, Fengyi Wang, Banglin Zhang, and Wenjie Dong. 2025. "Precipitation Microphysics Evolution of Typhoon During the Sharp Turn: A Case Study of Vongfong (2014)" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243984

APA StyleYe, G., Zhang, W., Leung, J. C.-H., Wang, F., Zhang, B., & Dong, W. (2025). Precipitation Microphysics Evolution of Typhoon During the Sharp Turn: A Case Study of Vongfong (2014). Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243984