Detecting Walnut Leaf Scorch Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Data, Genetic Algorithm, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine Learning Algorithms

Highlights

- An efficient monitoring model integrating UAV hyperspectral imagery and machine learning was developed for detecting walnut leaf scorch.

- The Genetic Algorithm-optimized SVM model (GA-SVM) achieved the highest predictive performance (R2 = 0.6302, RMSE = 0.0629, MAE = 0.0480).

- Offers a rapid and precise tool for the detection and precision management of walnut leaf scorch.

- The UAV-based approach enables site-specific disease detection, improves monitoring efficiency, and reduces reliance on costly manual ground surveys.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

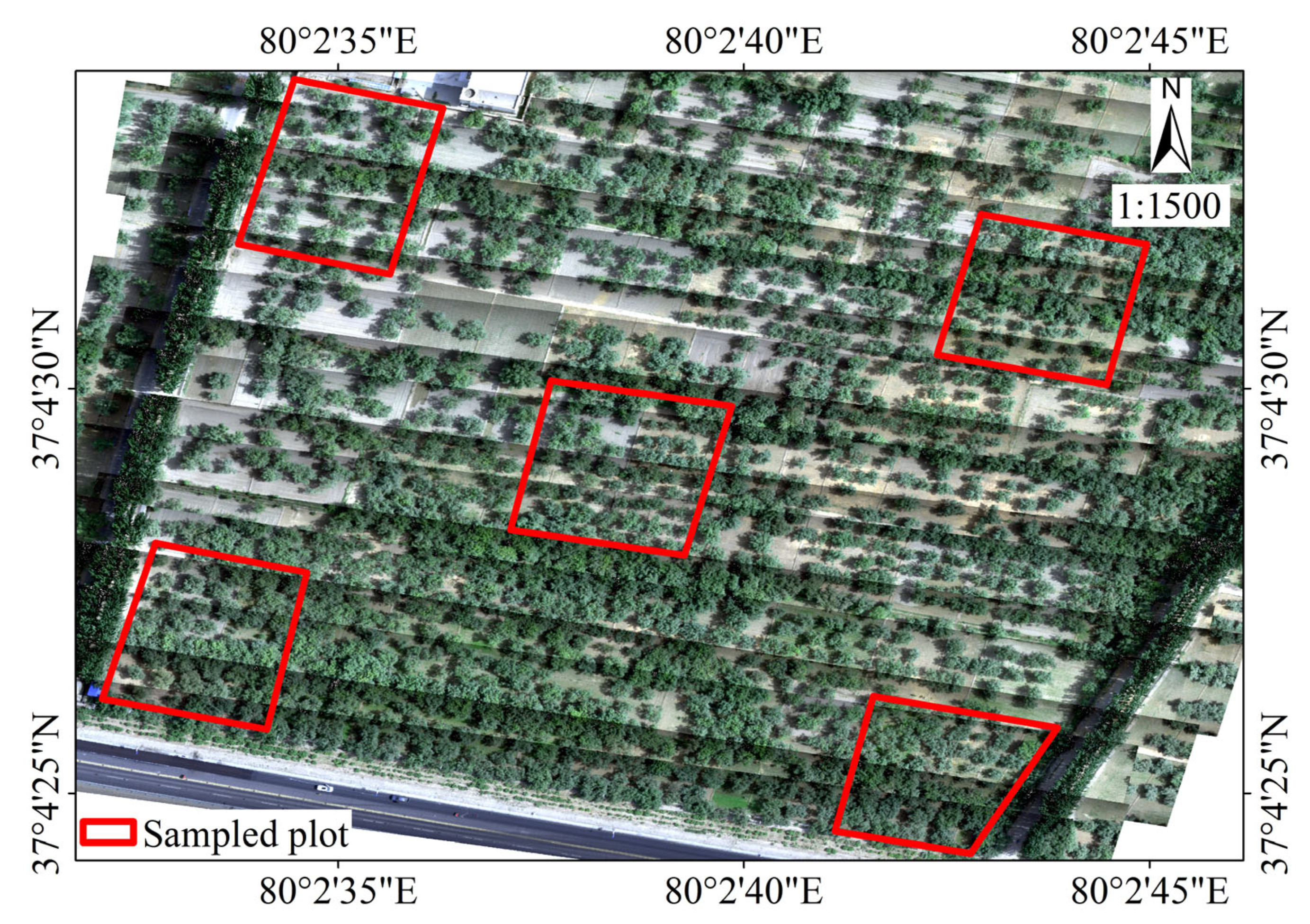

2.1. Study Area

2.2. The General Structure and Overall Workflow of This Study

2.3. Groud Data Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Sampling Design and Field Measurements

2.3.2. Ground Data Analysis Method

2.4. Hyperspectral Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.4.1. UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imagery Acquisition

2.4.2. Hyperspectral Imagery Preprocessing

2.5. Model Building

2.5.1. Random Forest

2.5.2. Support Vector Machine

2.5.3. Hyperparameter Optimization and Feature Selection

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Model Optimization Results

3.2. Comparative Performance and Visualization

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Development and Performance

4.2. Comparative Study and Future Perspective

4.2.1. Deep Learning

4.2.2. Multi-Source Remote Sensing Application

4.2.3. Spectral and Texture Indices

4.2.4. Canopy 3D Structure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, K.; Ma, J.; Cong, J.; Zhang, T.; Lei, H.; Xu, H.; Luo, Z.; Li, M. The road to reuse of walnut by-products: A comprehensive review of bioactive compounds, extraction and identification methods, biomedical and industrial applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, J. Research on the development strategy of Xinjiang walnut industry cluster. China Oils Fats 2025, 50, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B. Models for Estimating Foliar Mineral Nutrition Concentrations of Juglans regia ‘Xinxin2’ Using Spectral Reflectance. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Ürümqi, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- China News Service. How Xinjiang Forged a Ten-Billion-Yuan Industry Cluster from Walnuts? Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2023/12-30/10138171.shtml (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Li, Y.; Pu, S.; Mao, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q. Analysis on characteristics and causes of leaf scorch in walnut. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2022, 59, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jing, R.; Zou, Y.; Han, Y.; Ba, W.; Kheymo, A. Control technology for the physiological disease of “leaf margin scorch” in walnut. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. Technol. 2014, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, B. Study on causation of walnut withered leaf symptom in southern Xinjiang. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2012, 49, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Wang, S.; Pan, C.; Sattar, A.; Xing, C.; Hao, H.; Zhang, C. Evidence of the involvement of Xylella fastidiosa in the occurrence of walnut leaf scorch in Xinjiang, China. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Causes and control measures of walnut leaf scorch in Aksu. Rural Sci. Technol. 2014, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R. Study on Effect of Environmental Factors on Disease of Walnut Leaf Scorch in Xinjiang Shajingzi. Master’s Thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Jiang, P. Identification of the pathogens of walnut leaf spot disease. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2015, 52, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Dong, Y.; Huang, W.; Du, X.; Ren, B.; Huang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, H. A disease index for efficiently detecting wheat Fusarium head blight using Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 52181–52191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Peñuelas, J.; McCabe, M.F.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Atzberger, C.; Poblete, T.; Kumar, L.; Reynolds, M.P.; Nie, C. Hyperspectral remote sensing for monitoring crop disease: Applications, challenges, and perspectives. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, J.; Li, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhi, D.; Guang, Y.; Liu, W.; Qu, L.; Fu, X.; Zhao, H. Rapid large-scale monitoring of pine wilt disease using Sentinel-1/2 images in GEE. Forests 2025, 16, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.; Zhou, J.; Vories, E.; Sudduth, K.A. Evaluation of cotton emergence using UAV-based narrow-band spectral imagery with customized image alignment and stitching algorithms. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Hong, D.; Li, C.; Chanussot, J. SpectralMamba: Efficient Mamba for hyperspectral image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08489. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, A.F. Three decades of hyperspectral remote sensing of the earth: A personal view. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S5–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Monitoring of Pinus densiflora Bursaphelenchus xylophilus Disease Infection Stages. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nasi, R.; Honkavaara, E.; Lyytikainen-Saarenmaa, P.; Blomqvist, M.; Litkey, P.; Hakala, T.; Viljanen, N.; Kantola, T.; Tanhuanpaa, T.; Holopainen, M. Using UAV-Based photogrammetry and hyperspectral imaging for mapping bark beetle damage at tree-level. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 15467–15493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulridha, J.; Batuman, O.; Ampatzidis, Y. UAV-Based remote sensing technique to detect citrus canker disease utilizing hyperspectral imaging and machine learning. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, M.; Hu, J.; Pan, M.; Shen, L.; Ye, J.; Tan, J. Early diagnosis of pine wilt disease in Pinus thunbergii based on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Forests 2023, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Wu, D.; Qin, L. Preliminary study on data collecting and processing of unmanned airship low altitude hyperspectral remote sensing. Ecol. Environ. Monit. Three Gorges 2016, 1, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, D.; Ren, L. A machine learning algorithm to detect pine wilt disease using UAV-based hyperspectral imagery and Lidar data at the tree level. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2021, 101, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulridha, J.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Kakarla, S.C.; Roberts, P. Detection of target spot and bacterial spot diseases in tomato using UAV-Based and benchtop-based hyperspectral imaging techniques. Precis. Agric. 2019, 21, 955–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Huang, W.; Dong, Y.; Ye, H.; Ma, H.; Liu, B.; Wu, W.; Ren, Y.; Ruan, C.; Geng, Y. Wheat yellow rust detection using UAV-based hyperspectral technology. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, C.; Ma, Y.; Chen, X.; Lu, B.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R. Estimation of nitrogen concentration in walnut canopies in southern Xinjiang based on UAV multispectral images. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhao, R.; Tang, W.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Li, M.; et al. Estimation on powdery mildew of wheat canopy based on in-situ hyperspectral responses and characteristic wavelengths optimization. Crop Prot. 2024, 184, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Li, Y.; Moncada, J.D.S.; Johnson, W.; Lang, E.B.; Li, X.; Jin, J. Proximal hyperspectral imaging for early detection and disease development prediction of Septoria leaf blotch in wheat using spectral-temporal features. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.R.; Chen, G.; Berger, E.M.; Warrier, S.; Lan, G.; Grubert, E.; Dellaert, F.; Chen, Y. Dynamically controlled environment agriculture: Integrating machine learning and mechanistic and physiological models for sustainable food cultivation. ACS EST Eng. 2022, 2, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdoğan, G.; Gowen, A. Unveiling the potential: Harnessing spectral technologies for enhanced protein and gluten content prediction in wheat grains and flour. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemura, A.; Mutanga, O.; Sibanda, M.; Chidoko, P. Machine learning prediction of coffee rust severity on leaves using spectroradiometer data. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2018, 43, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelong, C.C.D.; Roger, J.-M.; Brégand, S.; Dubertret, F.; Lanore, M.; Sitorus, N.A.; Raharjo, D.A.; Caliman, J.-P. Evaluation of oil-palm fungal disease infestation with canopy hyperspectral reflectance data. Sensors 2010, 10, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Extraction of tree crowns damaged by Dendrolimus tabulaeformis Tsai et Liu via spectral-spatial classification using UAV-based hyperspectral images. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Karjalainen, M.; Dong, S.; Lu, R.; Wang, J.; Hyyppä, J. The effect of artificial intelligence evolving on hyperspectral imagery with different signal-to-noise ratio, spectral and spatial resolutions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, E.M.; Mutanga, O.; Rugege, D.; Ismail, R. Discriminating the papyrus vegetation (Cyperus papyrus L.) and its co-existent species using random forest and hyperspectral data resampled to HYMAP. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, A.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Boardman, J.W.; Brazile, J.; Bruzzone, L.; Camps-Valls, G.; Chanussot, J.; Fauvel, M.; Gamba, P.; Gualtieri, A.; et al. Recent advances in techniques for hyperspectral image processing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S110–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Mutanga, O.; Adam, E.; Ismail, R. Detecting Sirex noctilio grey-attacked and lightning-struck pine trees using airborne hyperspectral data, random forest and support vector machines classifiers. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 88, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, B.T.; Olugbara, O.O.; Marwala, T. Experimental comparison of support vector machines with random forests for hyperspectral image land cover classification. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 123, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoot, C.; Andersen, H.-E.; Moskal, L.M.; Babcock, C.; Cook, B.D.; Morton, D.C. Classifying forest type in the national forest inventory context with airborne hyperspectral and Lidar data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Valls, G.; Bruzzone, L. Kernel-based methods for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, S. Feature selection in machine learning: A new perspective. Neurocomputing 2018, 300, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.; Lee, H.-S.; Lee, J.-W. A review on multi-fidelity hyperparameter optimization in machine learning. ICT Express 2025, 11, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waske, B.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Arnason, K.; Sveinsson, J.R. Mapping of hyperspectral AVIRIS data using machine-learning algorithms. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 35, S106–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-L.; Wang, C.-J. A GA-based feature selection and parameters optimizationfor support vector machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 2006, 31, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Han, L.; He, L.; Yang, X. A GA-based feature selection and parameter optimization for linear support higher-order tensor machine. Neurocomputing 2014, 144, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Ai, B.; Qian, J. A genetic algorithm based wrapper feature selection method for classification of hyperspectral images using support vector machine. In Geoinformatics 2008 and Joint Conference on GIS and Built Environment: Classification of Remote Sensing Images, Proceedings of the 2008 SPIE, Guangzhou, China, 28–29 June 2008; Society of Photo Optical: Bellingham, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 7147, pp. 503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Shao, Y.-H.; Wu, T.-R. A GA-based model selection for smooth twin parametric-margin support vector machine. Pattern Recognit. 2013, 46, 2267–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, E.N.; Barbosa, B.H.G.; Silva, S.H.G.; Monti, C.A.U.; Tng, D.Y.P.; Gomide, L.R. Variable selection for estimating individual tree height using genetic algorithm and random forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 504, 119828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, H.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, D.; Huang, J. A GA and SVM classification model for pine wilt disease detection using UAV-based hyperspectral imagery. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Chatterji, S.; Pratihar, S. Feature selection using quantum inspired island model genetic algorithm for wheat rust disease detection and severity estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers in Computing and Systems, Goa, India, 13–15 December 2024; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 492, pp. 499–511. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, F.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.; Ali, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, S. Hyperspectral imaging combined with GA-SVM for maize variety identification. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3177–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y. Research on the Relative Poverty Management of Luopu County in Hetian Area. Master’s Thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Study on the Typical Experience of Poverty Alleviation in Industry and the Consolidation Path of Poverty Alleviation in Luopu County. Master’s Thesis, Tarim University, Alar, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Zhong, X.; Lei, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, T.; Sun, C.; Guo, W.; Sun, T.; Liu, S. Sampling survey method of wheat ear number based on UAV images and density map regression algorithm. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. First report of stem and root rot of coriander caused by Fusarium equiseti in China. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Guo, T.; Hao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Shu, J. Effects of leaf scorch on chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of walnut leaves. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2023, 130, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.-S.; Bock, C.H. Understanding the ramifications of quantitative ordinal scales on accuracy of estimates of disease severity and data analysis in plant pathology. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 47, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, M.; Mutanga, O.; Ismail, R. Examining the utility of random forest and AISA Eagle hyperspectral image data to predict Pinus patula age in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Geocarto Int. 2011, 26, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Ren, L.; Luo, Y. Early detection of pine wilt disease in Pinus tabuliformis in North China using a field portable spectrometer and UAV-based hyperspectral imagery. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, K. Early Detection of Mountain Pine Beetle Damage in Ponderosa Pine Forests of the Black Hills Using Hyperspectral and WorldView-2 Data. Master’s Thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Mubvumba, P.; Huang, Y.; Dhillon, J.; Reddy, K. Multi-stage corn yield prediction using high-resolution UAV multispectral data and machine learning models. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, G.; Abdelhamid, S.E.; Mallouhy, R.E.; Alghazo, J.; Kazimi, Z.A. Deep learning utilization in agriculture: Detection of rice plant diseases using an improved CNN model. Plants 2022, 11, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centorame, L.; Gasperini, T.; Ilari, A.; Del Gatto, A.; Foppa Pedretti, E. An overview of machine learning applications on plant phenotyping, with a focus on sunflower. Agronomy 2024, 14, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarle, W.S. Neural Network FAQ, Part 2 of 7: Learning. 1997. Available online: https://www.inf.ufsc.br/~aldo.vw/patrec/FAQ2.html (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; De Baets, B.; Verhoest, N.E.C.; Samson, R.; Degroeve, S.; De Becker, P.; Huybrechts, W. Random forests as a tool for ecohydrological distribution modelling. Ecol. Model. 2007, 207, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Drucker, H.; Burges, C.J.C.; Kaufman, L.; Smola, A.; Vapnik, V. Support Vector Regression Machines. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 9, Proceedings of the 1996 Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 2–5 December 1996; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 9, pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Vergun, S.; Deshpande, A.; Meier, T.B.; Song, J.; Tudorascu, D.L.; Nair, V.A.; Singh, V.; Biswal, B.B.; Meyerand, M.E.; Birn, R.M.; et al. Characterizing functional connectivity differences in aging adults using machine learning on resting state fMRI data. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, D.; Pal, S.; Patranabis, D.C. Support vector regression. Neural Inf. Process.-Lett. Rev. 2007, 11, 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Wien, F.T. Support vector machines. R News 2001, 1, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Demirtürk, B.; Harunoğlu, T. A comparative analysis of different machine learning algorithms developed with hyperparameter optimization in the prediction of student academic success. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-W.; Li, J.; Cao, G.-Y.; Tu, H.-Y.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Dynamic temperature modeling of an SOFC using least squares support vector machines. J. Power Sources 2008, 179, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aszemi, N.M.; Dominic, P.D.D. Hyperparameter optimization in convolutional neural network using genetic algorithms. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Li, J.; Chapman, M.; Deng, F.; Ji, Z.; Yang, X. Integration of orthoimagery and Lidar data for object-based urban thematic mapping using random forests. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 5166–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, G.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Khan, I.H.; Hussain, S.; Liu, J.; Weize, W.; Chen, M.; Cheng, T.; et al. Leveraging machine learning to discriminate wheat scab infection levels through hyperspectral reflectance and feature selection methods. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 161, 127372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-J. A Practical Guide to Support Vector Classification. 2003. Available online: https://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~cjlin/papers/guide/guide.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Fan, R.E.; Chen, P.H.; Lin, C.J. Working set selection using second order information for training support vector machines. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2005, 6, 1889–1918. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: Past, present, and future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, H.; Ceviz, Ö. Empirical enhancement of intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive approach with genetic algorithm-based hyperparameter tuning and hybrid feature selection. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 13025–13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Z.Y.; Abdullah, A.A.; Rashid, T.A. Optimizing feature selection with genetic algorithms: A review of methods and applications. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 9739–9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, N.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P.; Chen, C.; Cui, Z.; Chen, B.; Tan, T. Prediction of plasticizer property based on an improved genetic algorithm. Polymers 2022, 14, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrucca, L. GA: A package for genetic algorithms in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2013, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Chen, B.; Lu, X.; Bai, B.; Fan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, X. Integration of UAV multi-source data for accurate plant height and SPAD estimation in peanut. Drones 2025, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabdeh, A.N.; Al-Fugara, A.; Khedher, K.M.; Mabdeh, M.; Al-Shabeeb, A.R.; Al-Adamat, R. Forest fire susceptibility assessment and mapping using support vector regression and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system-based evolutionary algorithms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X. Object-based tree species classification using airborne hyperspectral images and LiDAR data. Forests 2019, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadbagher, E.; Marangoz, A.M.; Becek, K. Estimation of above-ground biomass using machine learning approaches with InSAR and LiDAR data in tropical peat swamp forest of Brunei Darussalam. Iforest-Biogeosci. For. 2024, 17, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Tie, N. Forest land resource information acquisition with Sentinel-2 image utilizing support vector machine, k-nearest neighbor, random forest, decision trees and multi-layer perceptron. Forests 2023, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Cho, S. Response modeling with support vector machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 2006, 30, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, T.; Ge, X.; Yin, F.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, W. A general maximal margin hyper-sphere SVM for multi-class classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedaie, A.; Najafi, A.A. Polar support vector machine: Single and multiple outputs. Neurocomputing 2016, 171, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, V.; Ma, Y. Practical selection of SVM parameters and noise estimation for SVM regression. Neural Netw. 2004, 17, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lameski, P.; Zdravevski, E.; Mingov, R.; Kulakov, A. SVM Parameter Tuning with Grid Search and Its Impact on Reduction of Model Over-Fitting. In Rough Sets, Fuzzy Sets, Data Mining, and Granular Computing; Yao, Y., Hu, Q., Yu, H., Grzymala-Busse, J.W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9437, pp. 464–474. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.; Tsangaratos, P.; Ilia, I.; Liu, J.; Zhu, A.-X.; Xu, C. Applying genetic algorithms to set the optimal combination of forest fire related variables and model forest fire susceptibility based on data mining models. The case of Dayu County, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Biedebach, L.; Kuepfer, A.; Neunhoeffer, M. The role of hyperparameters in machine learning models and how to tune them. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 2024, 12, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, Y.; Sharma, N.; Alsadoon, A. The accuracy of machine learning models relies on hyperparameter tuning: Student result classification using random forest, randomized search, grid search, bayesian, genetic, and optuna algorithms. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 74349–74364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.; Shah, N. Comparison of naive bayes and SVM classification in grid-search hyperparameter tuned and non-hyperparameter tuned healthcare stock market sentiment analysis. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yue, C.; Wang, J. An optimization framework with dimensionality reduction using Markov chain Monte Carlo and genetic algorithms for groundwater potential assessment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 111991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukawattanavijit, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. GA-SVM algorithm for improving land-cover classification using SAR and optical remote sensing data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Xu, K.; Zeng, P.; Zhang, W. GA-SVR algorithm for improving forest above ground biomass estimation using SAR data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 6585–6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, V.P.; Minh, L.N.; Lam, T.B. Feature Weighting and SVM parameters optimization based on genetic algorithms for classification problems. Appl. Intell. 2017, 46, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyerr, B.A.; Adewumi, A.O.; Ali, M.M. Real-coded genetic algorithm with uniform random local search. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 228, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarif, I.; Prugel-Bennett, A.; Wills, G. SVM Parameter optimization using grid search and genetic algorithm to improve classification performance. TELKOMNIKA Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control 2016, 14, 1502–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Bruzzone, L.; Guan, R.; Zhou, F.; Yang, C. Spectral-spatial genetic algorithm-based unsupervised band selection for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 9616–9632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Pu, R.; Gonzalez-Moreno, P.; Yuan, L.; Wu, K.; Huang, W. Monitoring plant diseases and pests through remote sensing technology: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 165, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tong, T.; Luo, T.; Wang, J.; Rao, Y.; Li, L.; Jin, D.; Wu, D.; Huang, H. Retrieving the infected area of pine wilt disease-disturbed pine forests from medium-resolution satellite images using the stochastic radiative transfer theory. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Valdecantos, P.; Egea, G.; Borrero, C.; Perez-Ruiz, M.; Aviles, M. Detection of Fusarium wilt-induced physiological impairment in strawberry plants using hyperspectral imaging and machine learning. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2958–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.H.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Cao, A.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Cheng, T.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; et al. Early detection of powdery mildew disease and accurate quantification of its severity using hyperspectral images in wheat. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, M.; Ashourloo, D.; Aghighi, H.; Radiom, S.; Alimohammadi, A. Wheat leaf rust detection at canopy scale under different LAI levels using machine learning techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tian, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J. Estimation of disease severity for downy mildew of greenhouse cucumber based on visible spectral and machine learning. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020, 40, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ashourloo, D.; Mobasheri, M.; Huete, A. Developing two spectral disease indices for detection of wheat leaf rust (Puccinia triticina). Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4723–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sothe, C.; De Almeida, C.M.; Schimalski, M.B.; La Rosa, L.E.C.; Castro, J.D.B.; Feitosa, R.Q.; Dalponte, M.; Lima, C.L.; Liesenberg, V.; Miyoshi, G.T.; et al. Comparative performance of convolutional neural network, weighted and conventional support vector machine and random forest for classifying tree species using hyperspectral and photogrammetric data. GIScience Remote Sens. 2020, 57, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.E.; Madamidola, O.A.; Awotunde, J.B.; Misra, S.; Agrawal, A. Comparative Analysis of CNN and SVM Machine Learning Techniques for Plant Disease Detection. In Data Engineering and Applications; Agrawal, J., Shukla, R.K., Sharma, S., Shieh, C.-S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1146, pp. 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, B.; Zhou, T.; Liu, B.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Plaza, A. Multi-scale autoencoder suppression strategy for hyperspectral image anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 5115–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Guan, R.; Peng, Z.; Xu, C.; Shi, Y.; Ding, W.; Gee Lim, E.; Yue, Y.; Seo, H.; Lok Man, K.; et al. Exploring radar data representations in autonomous driving: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 7401–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Yun, L. RSWD-YOLO: A walnut detection method based on UAV remote sensing images. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J.-Z.; Song, D.-R.; Song, C.-M.; Wang, X.-H. Multi-band remote sensing image sharpening: A survey. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2023, 43, 2999–3008. [Google Scholar]

- Sa, H.-Y.; Huang, X.; Ling, L.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, J.; Bao, G.; Tong, S.; Bao, Y.; Ganbat, D.; Ariunaa, M.; et al. Multi-dimensional estimation of leaf loss rate from larch caterpillar under insect pest stress using UAV-based multi-source remote sensing. Drones 2025, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Sun, T. Applicability of UAV-based optical imagery and classification algorithms for detecting pine wilt disease at different infection stages. GIScience Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2170479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Song, L.; Duan, J.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Feng, W. Monitoring wheat powdery mildew based on hyperspectral, thermal infrared, and RGB image data fusion. Sensors 2022, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Yu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, L.; Luo, Y. Fusion of UAV hyperspectral imaging and LiDAR for the early detection of EAB stress in Ash and a new EAB detection index—NDVI (776,678). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankey, T.; Donager, J.; McVay, J.; Sankey, J.B. UAV Lidar and hyperspectral fusion for forest monitoring in the southwestern USA. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Jia, G.; Zhou, X.; Song, N.; Wu, J.; Gao, K.; Huang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Q. Adaptive high-speed echo data acquisition method for bathymetric LiDAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, S.; Harfouche, A.; Maesano, M.; Balestra, G.M. UAV-based thermal, RGB imaging and gene expression analysis allowed detection of Fusarium head blight and gave new insights into the physiological responses to the disease in durum wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 628575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, C.; Rong, G.; Wei, S.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Sudu, B.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J. Dynamic evaluation of agricultural drought hazard in Northeast China based on coupled multi-source data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utla, C.S.; Dashora, A.; Mishra, R.K.; Zhang, Y. A review on aboveground biomass estimation methods utilizing forest structural characteristics. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 5917–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, W.; Guo, T. Advances in thermal infrared remote sensing technology for geothermal resource detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Chang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Xie, H. A precise method for identifying 3-D circles in freeform surface point clouds. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, B.; Hong, D.; Hang, R.; Ghamisi, P.; Kang, X.; Chanussot, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Feature extraction for hyperspectral imagery: The evolution from shallow to deep: Overview and toolbox. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2020, 8, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szantoi, Z.; Escobedo, F.J.; Abd-Elrahman, A.; Pearlstine, L.; Dewitt, B.; Smith, S. Classifying spatially heterogeneous wetland communities using machine learning algorithms and spectral and textural features. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarira, D.; Mutanga, O.; Naidu, M. Google Earth Engine for informal settlement mapping: A random forest classification using spectral and textural information. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Lin, F.; Yin, X.; Gu, C.; Qiao, H. Development and evaluation of a new spectral disease index to detect wheat Fusarium head blight using hyperspectral imaging. Sensors 2020, 20, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.; Huang, W.; Ye, H.; Dong, Y.; Ma, H.; Ren, Y.; Ruan, C. Identification of wheat yellow rust using spectral and texture features of hyperspectral images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Ji, X.; He, Q.; Gong, Z.; Sun, H.; Wen, T.; Guo, W. Monitoring of wheat Fusarium head blight on spectral and textural analysis of UAV multispectral imagery. Agriculture 2023, 13, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Bai, T.; Yuan, X.; Bao, H.; He, D.; Sun, W.; He, Y. Cotton Verticillium wilt monitoring based on UAV multispectral-visible multi-source feature fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Chang, Q. Estimation of chlorophyll content in apple leaves infected with mosaic disease by combining spectral and textural information using hyperspectral images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gara, T.W.; Skidmore, A.K.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Wang, T. Leaf to canopy upscaling approach affects the estimation of canopy traits. GIScience Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 554–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Huete, A.; Li, L. Effects of forest canopy vertical stratification on the estimation of gross primary production by remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, G.; Qi, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, C.; Xu, B.; Wu, B.; Su, X.; Zhao, C. The impacts of tree shape, disease distribution and observation geometry on the performances of disease spectral indices of apple trees. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 329, 114953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, B.; Ellsasser, F.J.; Awawdeh, M.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.; Almahasneh, L.; Elberink, S.O.; Abuhamoor, D.; Al Asmar, Y. Remote sensing technologies using UAVs for pest and disease monitoring: A review centered on date palm trees. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, J.; Koch, B. Exploring full-waveform LiDAR parameters for tree species classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2011, 13, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni-Meister, W.; Yang, W.; Kiang, N.Y. A clumped-foliage canopy radiative transfer model for a global dynamic terrestrial ecosystem model. I: Theory. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, M.; Ishihara, M.I.; Doi, K.; Hara, T. Determination of species-specific leaf angle distribution and plant area index in a cool-temperate mixed forest from UAV and upward-pointing digital photography. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 325, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wan, Y.; Gao, D.; Cao, P. LiDAR-assisted UAV variable-rate spraying system. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease Grade | Representative Value | Grading Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Grade I (b0) | 0 | The scorched area of leaves is 0 |

| Grade II (b1) | 1 | 0–25% of leaf area in diseased leaves become scorched |

| Grade III (b2) | 2 | 26–50% of the diseased leaves become brown and scorched |

| Grade IV (b3) | 3 | 51–75% of the diseased leaves become brown and scorched |

| Grade V (b4) | 4 | 76–100% of the diseased leaves become scorched |

| Optimization Method | Model | Optimal Hyperparameters | No. of Features | Selection Criterion (Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | GS-RF | ntree: 600, mtry: 38, mtry factor: 0.5 | 231 | Min. RMSE (0.0754 ± 0.0103) |

| GS-SVM | C: 211, γ: 2−11, ε: 2−5 | 231 | Min. RMSE (0.0683 ± 0.0081) | |

| Genetic Algorithm | GA-RF | ntree: 400, mtry: 27, mtry factor: 0.75 | 108 | Max. Fitness (0.4115) |

| GA-SVM | C: 211, γ: 2−11, ε: 2−2 | 96 | Max. Fitness (0.4966) |

| WLS-UAV Dataset | Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | GS-RF | 0.9226 | 0.0303 | 0.0229 |

| GS-SVM | 0.6882 | 0.0608 | 0.0431 | |

| GA-RF | 0.9216 | 0.0305 | 0.0232 | |

| GA-SVM | 0.6647 | 0.0631 | 0.0480 | |

| Test | GS-RF | 0.5260 | 0.0712 | 0.0554 |

| GS-SVM | 0.5997 | 0.0654 | 0.0498 | |

| GA-RF | 0.5331 | 0.0707 | 0.0550 | |

| GA-SVM | 0.6302 | 0.0629 | 0.0480 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Meng, J. Detecting Walnut Leaf Scorch Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Data, Genetic Algorithm, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3986. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243986

Weng J, Zhang Q, Wang B, Zhang C, Zhang H, Meng J. Detecting Walnut Leaf Scorch Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Data, Genetic Algorithm, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3986. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243986

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeng, Jian, Qiang Zhang, Baoqing Wang, Cuifang Zhang, Heyu Zhang, and Jinghui Meng. 2025. "Detecting Walnut Leaf Scorch Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Data, Genetic Algorithm, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine Learning Algorithms" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3986. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243986

APA StyleWeng, J., Zhang, Q., Wang, B., Zhang, C., Zhang, H., & Meng, J. (2025). Detecting Walnut Leaf Scorch Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Data, Genetic Algorithm, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3986. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243986