Spatial Consistency and Accuracy Assessment of Grassland Classification in the Sanjiangyuan Region: From Six Medium Resolution Land Cover Products

Highlights

- Evaluation of six global medium-resolution land cover products for grassland mapping in the Sanjiangyuan Region.

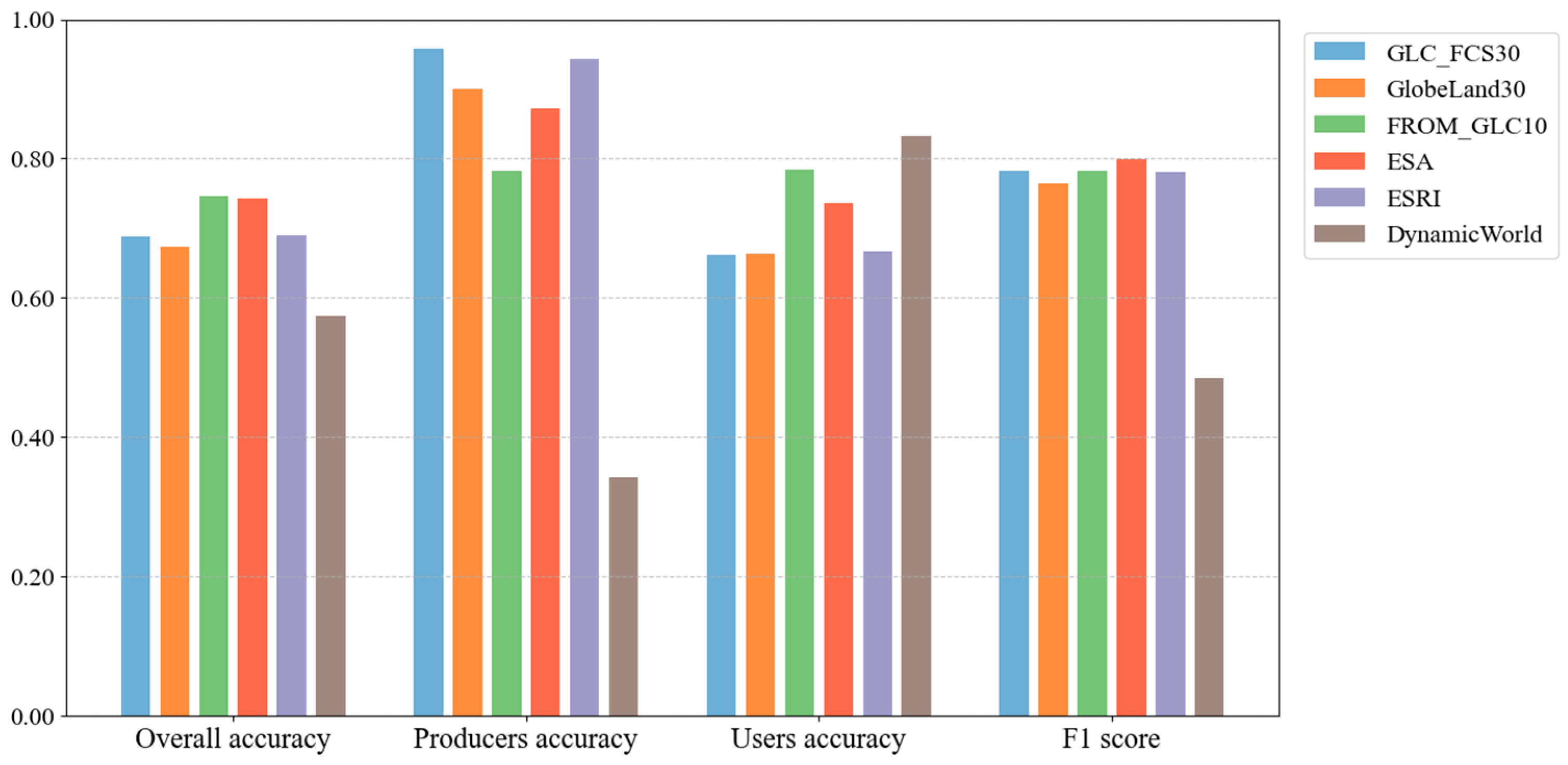

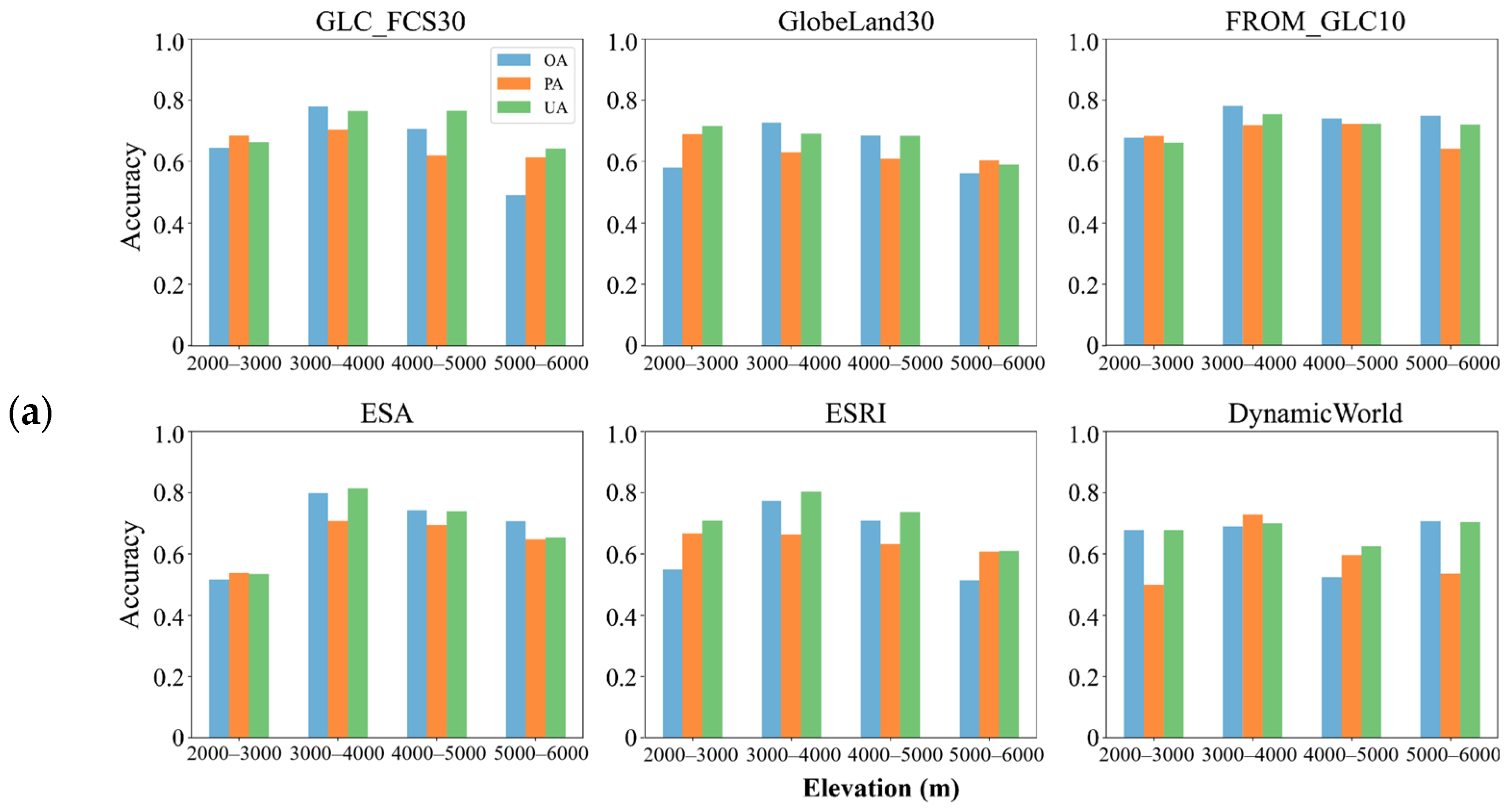

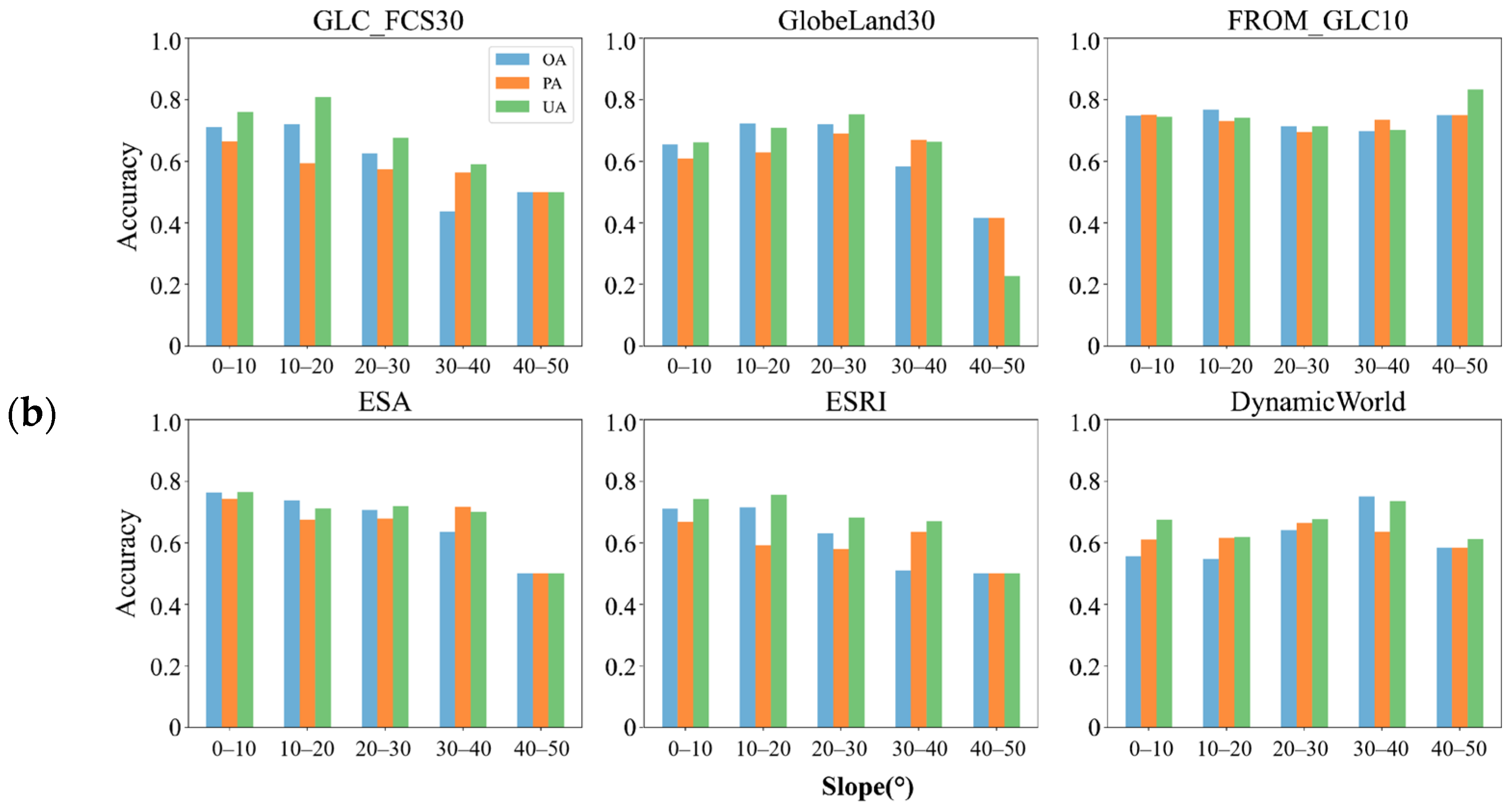

- Highest accuracy of ESA and FROM_GLC10, and lowest performance of Dynamic World, with results influenced by topography.

- Reliable reference for selecting suitable products for alpine grassland monitoring.

- Guidance for product fusion and fine-scale classification in high-altitude ecosystems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Publicly Available Land Cover Products

2.2.2. Other Data

- (1)

- Validation Sample Data

- (2)

- Topographic Data

- (3)

- Grassland Area Statistics Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Grassland Area Statistics from Six Land Cover Products

2.3.2. Consistency Analysis

- (1)

- Pairwise Consistency Analysis via the Jaccard Index

- (2)

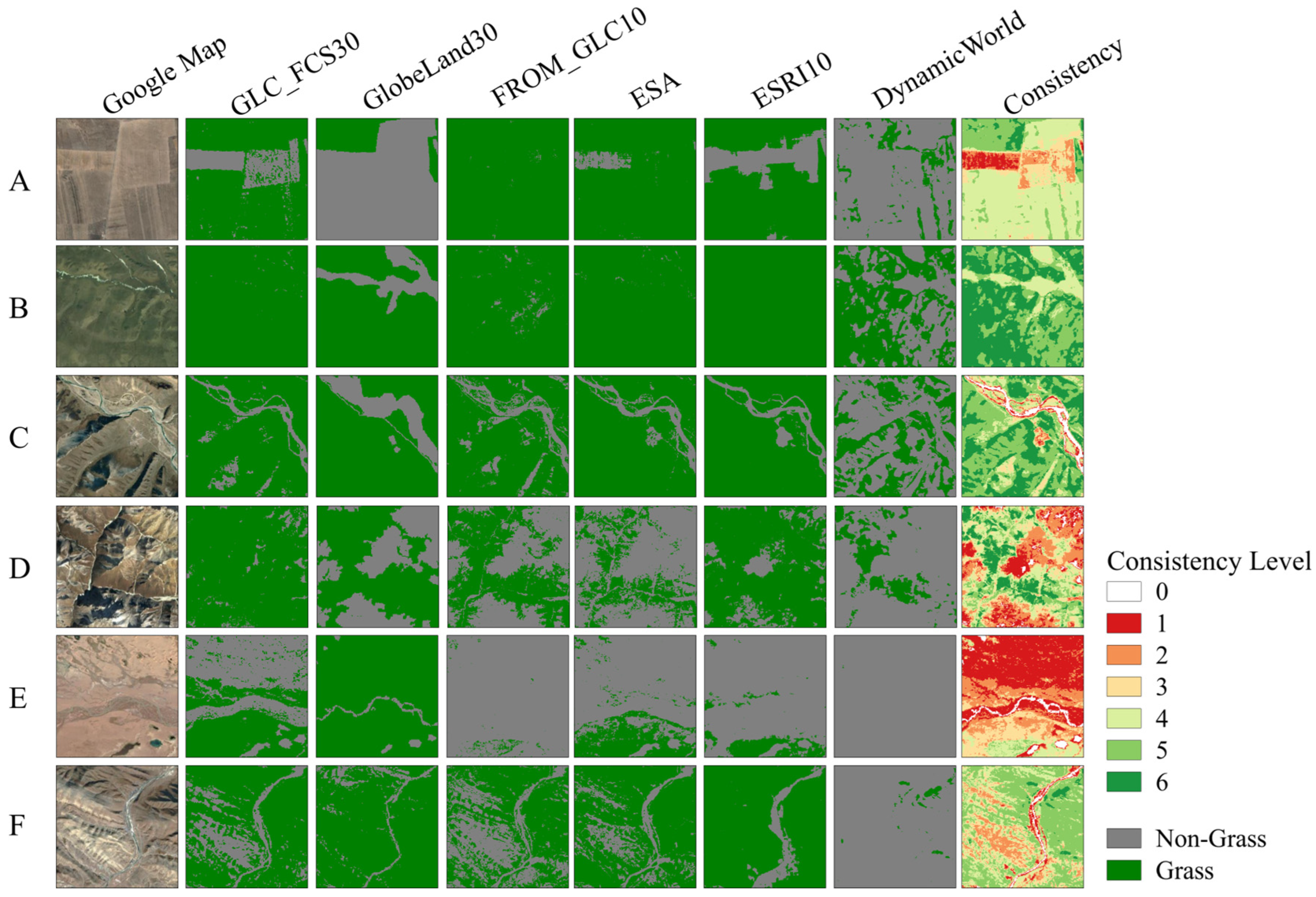

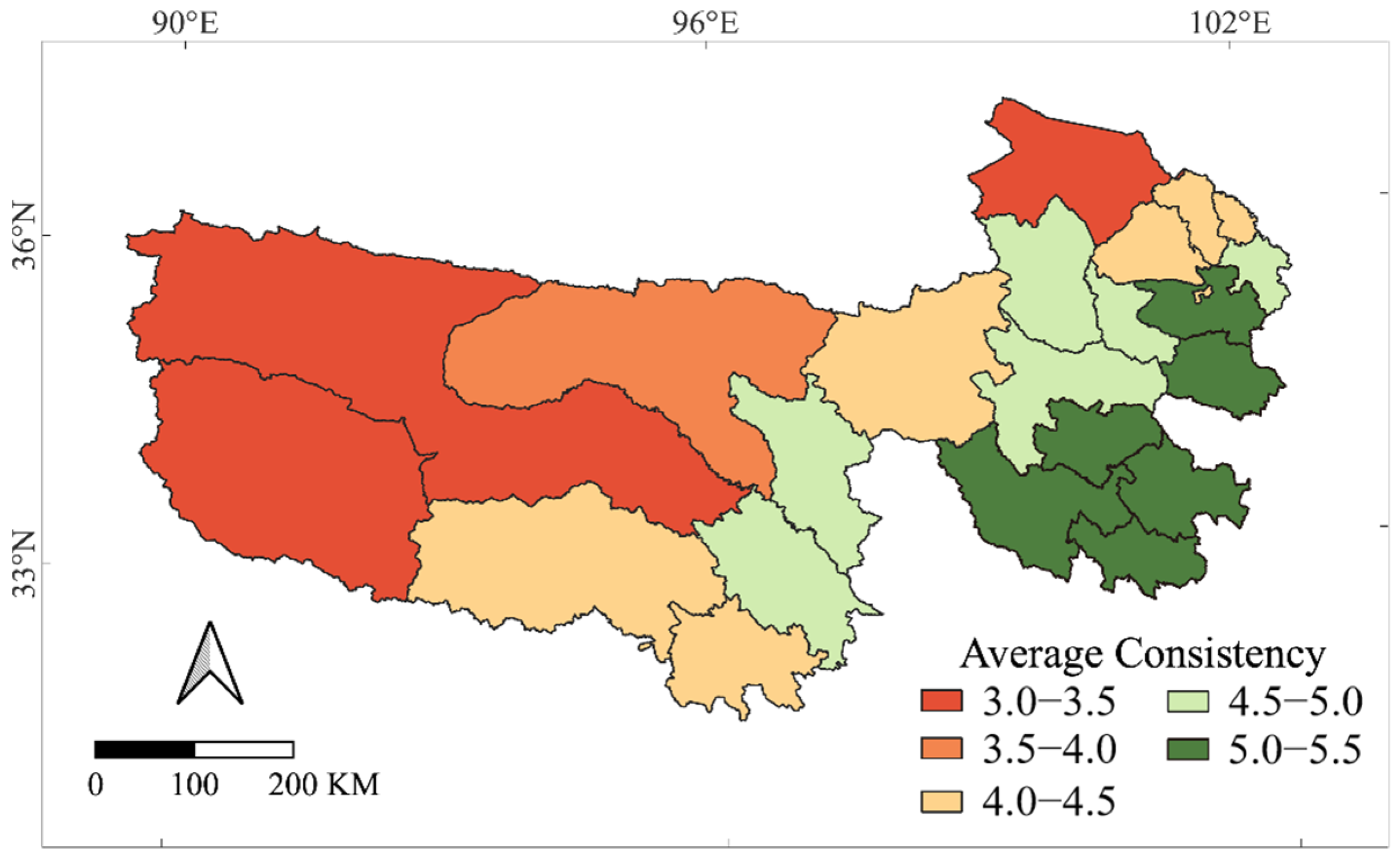

- Spatial Consistency Analysis

2.3.3. Confusion Matrix and Accuracy Assessment

- True Positive (TP): actually grassland and predicted as grassland;

- False Positive (FP): actually non-grassland and predicted as grassland;

- True Negative (TN): actually non-grassland and predicted as non-grassland;

- False Negative (FN): actually grassland and predicted as non-grassland.

3. Results

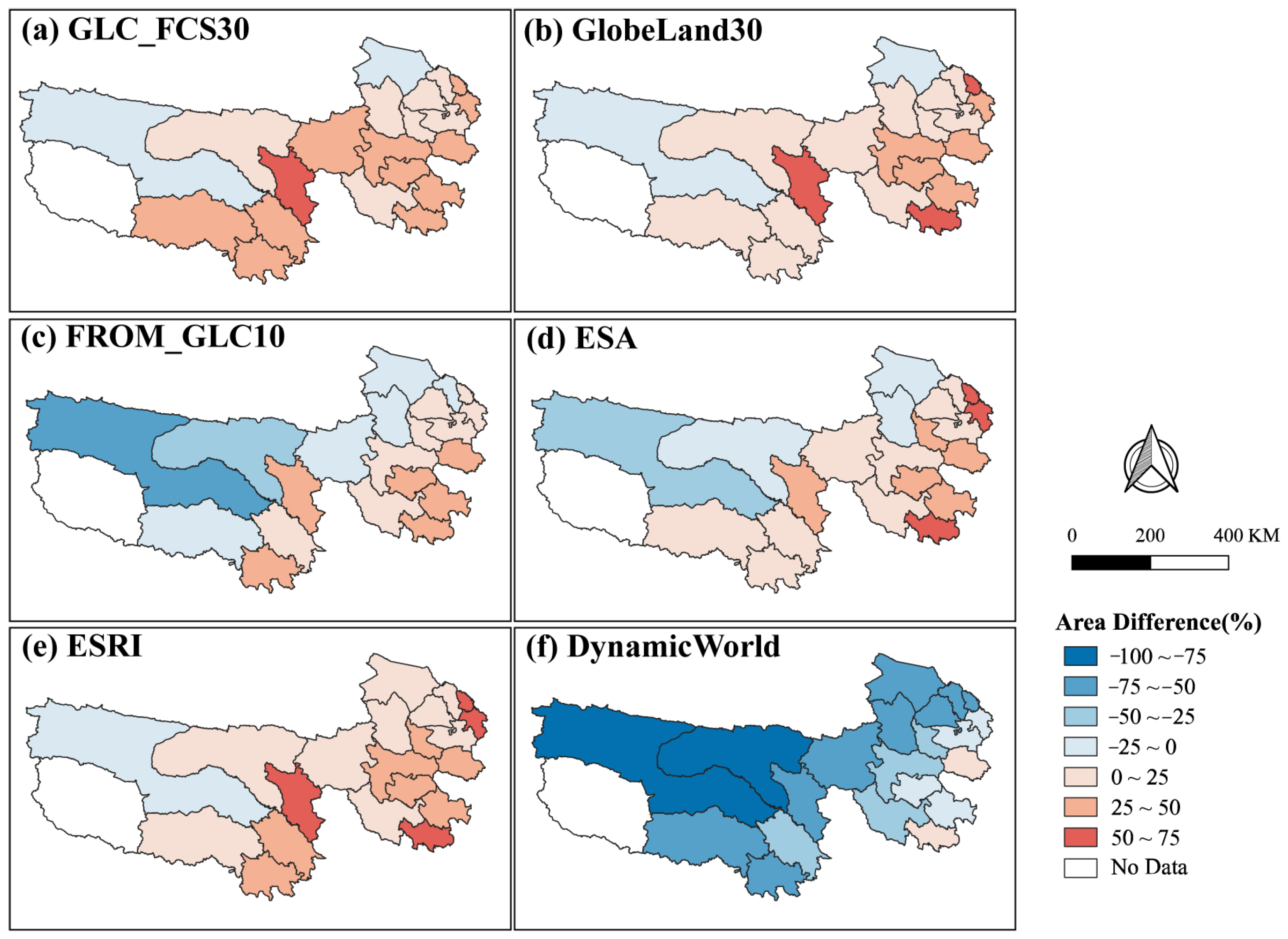

3.1. Analysis of Six Land Cover Products Based on Area

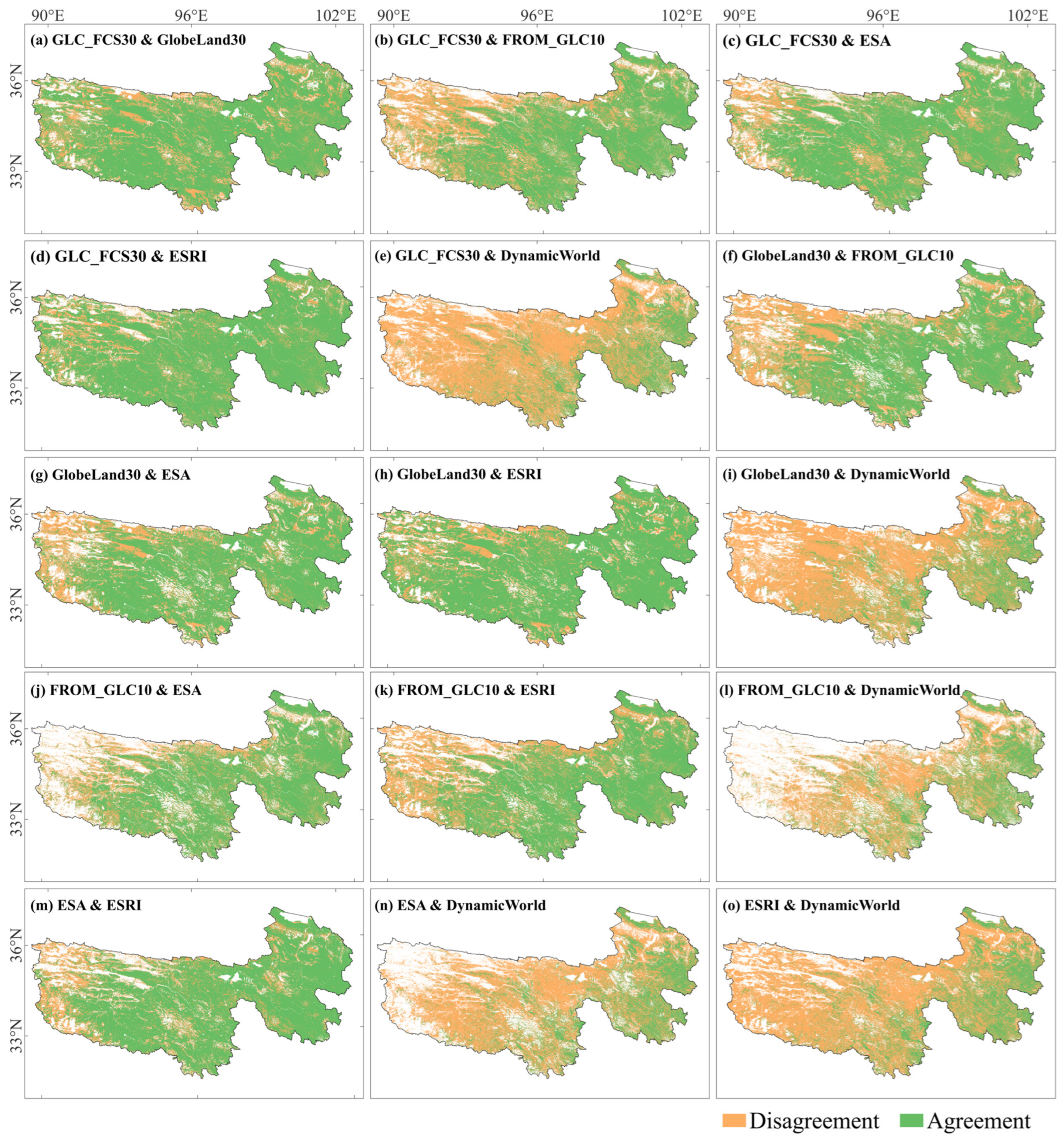

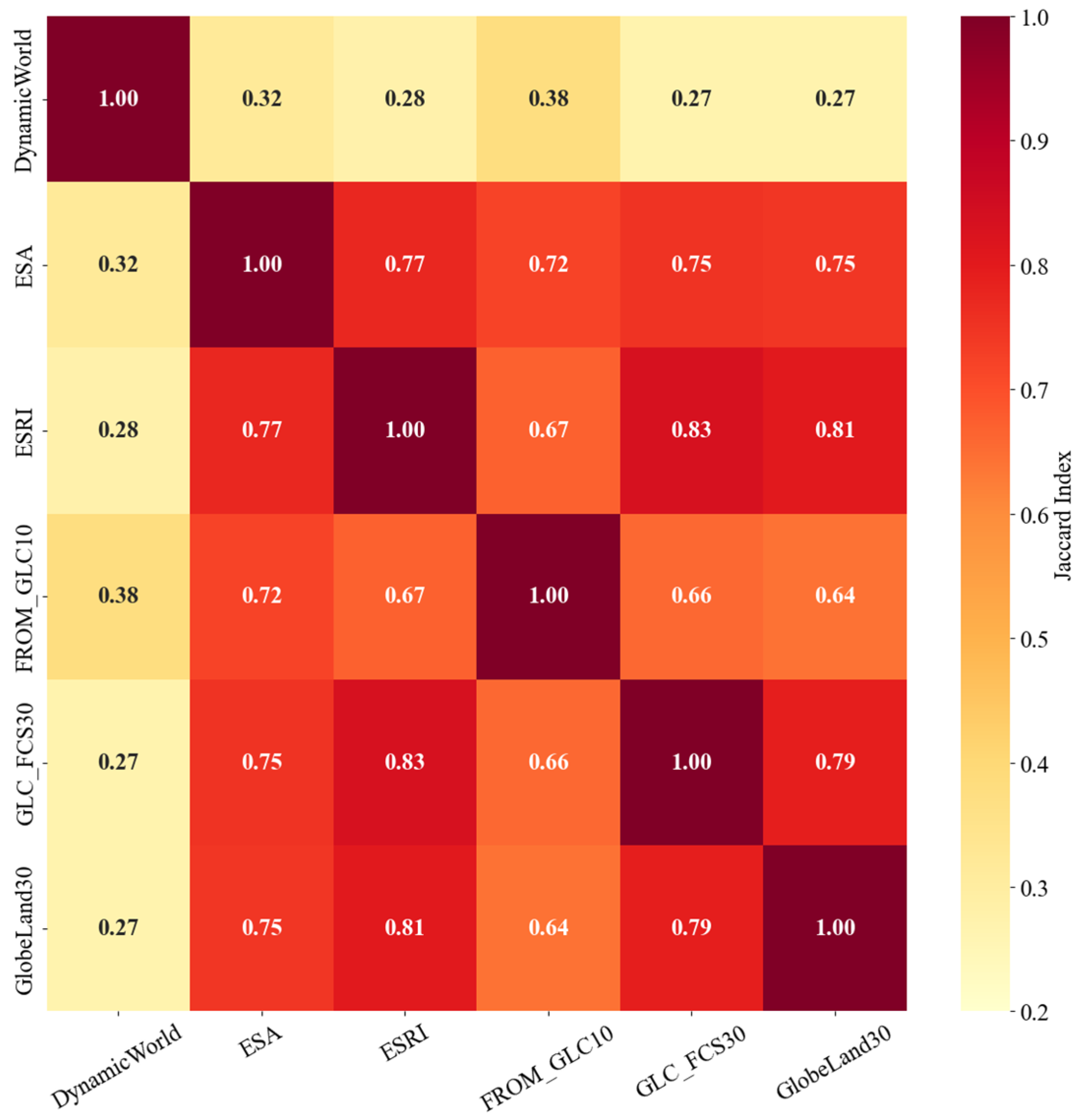

3.2. Pairwise Consistency of Six Products

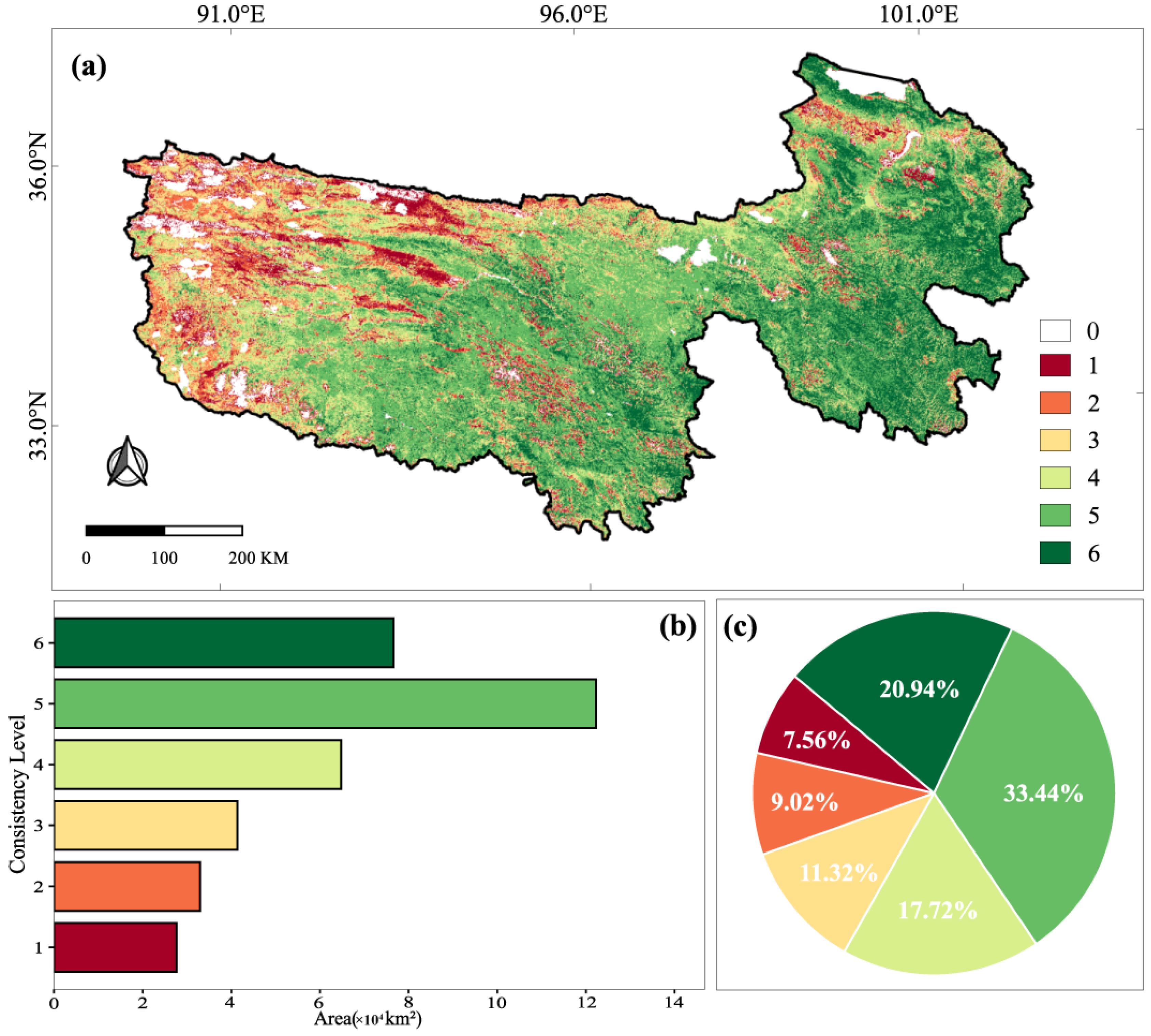

3.3. Grassland Spatial Consistency of Six Products

3.4. Grassland Classification Accuracy of Six Products

3.4.1. Accuracy Comparison of Six Products for Grassland in the SJYR

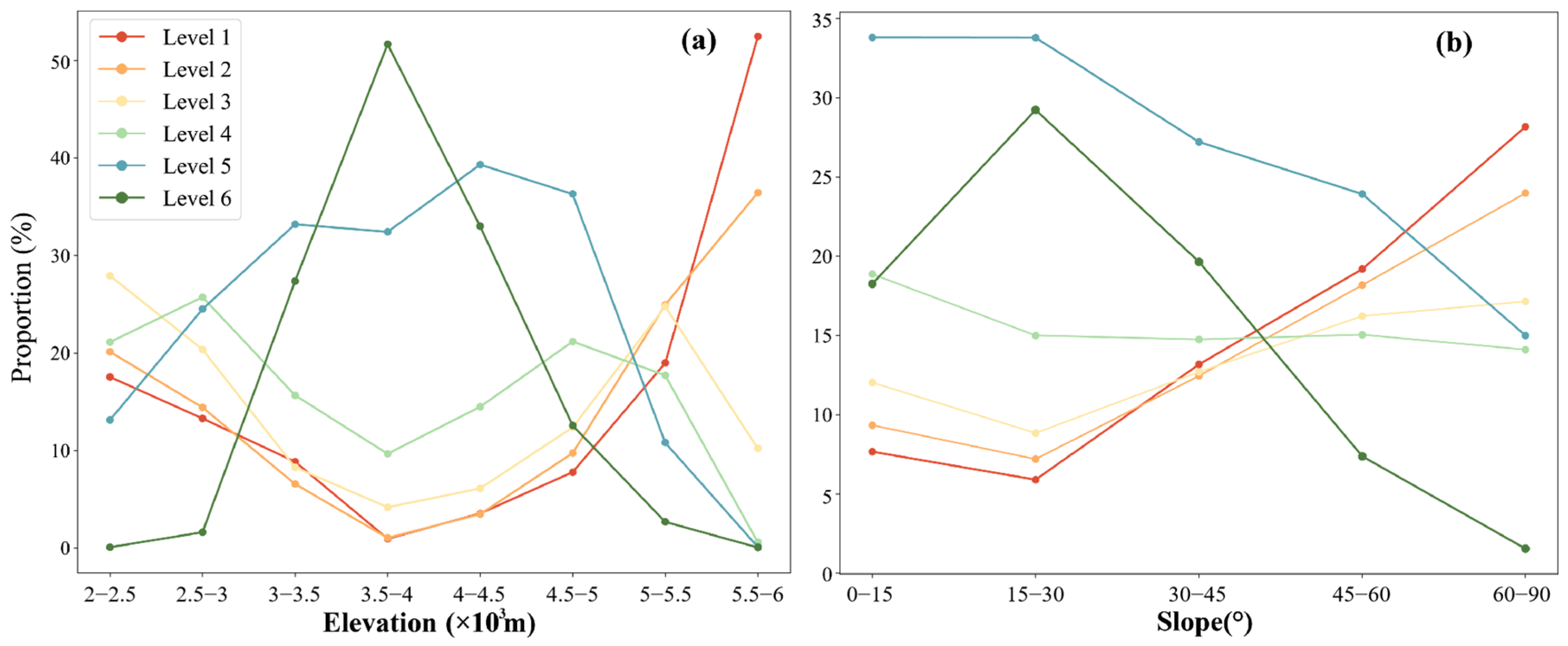

3.4.2. Accuracy Comparison of Grassland in Different Topographical Conditions

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Factors of the Uncertainty in Grassland Classification Results

4.2.1. Differences in Remote Sensing Data Sources

4.2.2. Differences in Classification Methods and Classification Systems

4.2.3. Differences in Temporal Reference

4.3. Recommendations for Future Grassland Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blair, J.; Nippert, J.; Briggs, J. Grassland Ecology. In Ecology and the Environment; Monson, R.K., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-1-4614-7612-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, J.; Bullock, J.M.; Egoh, B.; Everson, C.; Everson, T.; O’Connor, T.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Smith, H.G.; Lindborg, R. Grasslands—More Important for Ecosystem Services than You Might Think. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Ciais, P.; Gasser, T.; Smith, P.; Herrero, M.; Havlík, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Guenet, B.; Goll, D.S.; Li, W.; et al. Climate Warming from Managed Grasslands Cancels the Cooling Effect of Carbon Sinks in Sparsely Grazed and Natural Grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholtz, R.; Twidwell, D. The Last Continuous Grasslands on Earth: Identification and Conservation Importance. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2022, 4, e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Gao, J.; Brierley, G.; Qiao, Y.-M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.-W. Rangeland Degradation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Implications for Rehabilitation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2013, 24, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.P.; Faber-Langendoen, D.; Josse, C.; Morrison, J.; Loucks, C.J. Distribution Mapping of World Grassland Types. J. Biogeogr. 2014, 41, 2003–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayiah, M.; Dong, S.; Khomera, S.W.; Ur Rehman, S.A.; Yang, M.; Xiao, J. Status and Challenges of Qinghai–Tibet Plateau’s Grasslands: An Analysis of Causes, Mitigation Measures, and Way Forward. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Yan, C.; Xing, X.; Jia, H.; Wei, X.; Feng, K. Spatial-Temporal Changes and Driving Forces of Aeolian Desertification of Grassland in the Sanjiangyuan Region from 1975 to 2015 Based on the Analysis of Landsat Images. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 193, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Liu, X.; Zou, X.; Wang, Z. Impacts of Climate Variations and Human Activities on the Net Primary Productivity of Different Grassland Types in the Three-River Headwaters Region. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jia, L.; Cai, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, T.; Huang, A.; Fan, D. Assessment of Grassland Degradation on the Tibetan Plateau Based on Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Du, Q. Study on the Landcover Changes Based on GIS and RS Technologies: A Case Study of the Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve in the Hinterland Tibet Plateau, China. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2022, 10, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yan, G.; Ma, M.; Zhou, S.; Qian, Y. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of China’s Ecological Civilization Progress after Implementing National Conservation Strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Su, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Xu, W.; Min, Q.; Zhang, H. Theoretical Debates and Innovative Practices of the Development of China’s Nature Protected Area under the Background of Ecological Civilization Construction. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 839–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Brierley, G.; Shi, D.; Xie, Y.; Sun, H. Ecological Protection and Restoration in Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve, Qinghai Province, China. In Perspectives on Environmental Management and Technology in Asian River Basins; Higgitt, D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 93–120. ISBN 978-94-007-2330-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lee, T.M. Altitude Dependence of Alpine Grassland Ecosystem Multifunctionality across the Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haack, B.; English, R. National Land Cover Mapping by Remote Sensing. World Dev. 1996, 24, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Chanussot, J.; Hong, D.; Yao, J.; Gao, L. Progress and Challenges in Intelligent Remote Sensing Satellite Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Liu, H.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, Y.; An, S.; Yuan, M.; Wang, G.; Long, T.; Peng, Y.; et al. Remote Sensing Data Intelligence: Progress and Perspectives. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2025, 27, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qi, B.; He, G.; Wang, M.; Huang, S.; Long, T.; Wang, G.; Xu, Z. High Resolution Global Forest Burned Area Changes Monitoring Using Landsat 7/8 Images. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, T.R.; Reed, B.C.; Brown, J.F.; Ohlen, D.O.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, L.; Merchant, J.W. Development of a Global Land Cover Characteristics Database and IGBP DISCover from 1 Km AVHRR Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 1303–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Defries, R.S.; Townshend, J.R.G.; Sohlberg, R. Global Land Cover Classification at 1 Km Spatial Resolution Using a Classification Tree Approach. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 1331–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomé, E.; Belward, A.S. GLC2000: A New Approach to Global Land Cover Mapping from Earth Observation Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 1959–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, M.A.; McIver, D.K.; Hodges, J.C.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Muchoney, D.; Strahler, A.H.; Woodcock, C.E.; Gopal, S.; Schneider, A.; Cooper, A.; et al. Global Land Cover Mapping from MODIS: Algorithms and Early Results. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arino, O.; Gross, D.; Ranera, F.; Leroy, M.; Bicheron, P.; Brockman, C.; Defourny, P.; Vancutsem, C.; Achard, F.; Durieux, L.; et al. GlobCover: ESA Service for Global Land Cover from MERIS. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Barcelona, Spain, 23–28 July 2007; pp. 2412–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H. Comparison and Evaluation of Five Global Land Cover Products on the Tibetan Plateau. Land 2024, 13, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liao, A.; Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Han, G.; Peng, S.; Lu, M.; et al. Global Land Cover Mapping at 30 m Resolution: A POK-Based Operational Approach. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 103, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Xie, S.; Mi, J. GLC_FCS30: Global Land-Cover Product with Fine Classification System at 30 m Using Time-Series Landsat Imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 2753–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, L.; Niu, Z.; Huang, X.; Fu, H.; Liu, S.; et al. Finer Resolution Observation and Monitoring of Global Land Cover: First Mapping Results with Landsat TM and ETM+ Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 2607–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Clinton, N.; Ji, L.; Li, W.; Bai, Y.; et al. Stable Classification with Limited Sample: Transferring a 30-m Resolution Sample Set Collected in 2015 to Mapping 10-m Resolution Global Land Cover in 2017. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaga, D.; Van De Kerchove, R.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Souverijns, N.; Brockmann, C.; Quast, R.; Wevers, J.; Grosu, A.; Paccini, A.; Vergnaud, S.; et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2020 V100 2021. The European Space Agency: Paris, France, 2021. Available online: https://worldcover2020.esa.int/download (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Karra, K.; Kontgis, C.; Statman-Weil, Z.; Mazzariello, J.C.; Mathis, M.; Brumby, S.P. Global Land Use/Land Cover with Sentinel 2 and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 4704–4707. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.F.; Brumby, S.P.; Guzder-Williams, B.; Birch, T.; Hyde, S.B.; Mazzariello, J.; Czerwinski, W.; Pasquarella, V.J.; Haertel, R.; Ilyushchenko, S.; et al. Dynamic World, near Real-Time Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Mapping. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaife, T.; Quegan, S.; Disney, M.; Lewis, P.; Lomas, M.; Woodward, F.I. Impact of Land Cover Uncertainties on Estimates of Biospheric Carbon Fluxes. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22, GB4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Li, S.; Wen, L. Impacts of Land Use/Land Cover Distributions on Permafrost Simulations on Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Feng, X.; Li, H. Accuracy Assessment of Seven Global Land Cover Datasets over China. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 125, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Tsendbazar, N.-E.; Herold, M.; De Bruin, S.; Koopmans, M.; Birch, T.; Carter, S.; Fritz, S.; Lesiv, M.; Mazur, E.; et al. Comparative Validation of Recent 10 m-Resolution Global Land Cover Maps. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Wang, S.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, D.; Zhao, L. Consistency Assessments of the Land Cover Products on the Tibetan Plateau. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 5652–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, B.; Gong, D.; Li, L. Spatial Consistency and Accuracy Analysis of Multi-Source Land Cover Products on the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Liang, X.; Yan, C.; Xing, X.; Jia, H.; Wei, X.; Feng, K. Vegetation Dynamic Changes and Their Response to Ecological Engineering in the Sanjiangyuan Region of China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, F.; Guo, A.; Zhu, X. Study on the Climate Change Trend and Its Catastrophe over “Sanjiangyuan” Region in Recent 43 Years. J. Nat. Resour. 2006, 21, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Zhang, J.; Song, P.; Qin, W.; Wang, H.; Cai, Z.; Gao, H.; Liu, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, T. Identifying Priority Reserves Favors the Sustainable Development of Wild Ungulates and the Construction of Sanjiangyuan National Park. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Tang, R.; Li, J.; Tang, H.; Guo, Z. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Landscape Pattern and Vegetation Ecological Quality in Sanjiangyuan National Park. Sustainability 2025, 17, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehe, G.; Schleuss, P.-M.; Seeber, E.; Babel, W.; Biermann, T.; Braendle, M.; Chen, F.; Coners, H.; Foken, T.; Gerken, T.; et al. The Kobresia Pygmaea Ecosystem of the Tibetan Highlands—Origin, Functioning and Degradation of the World’s Largest Pastoral Alpine Ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Chakraborty, T.; Simensen, T.; Singh, G. Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Datasets: A Comparison of Dynamic World, World Cover and Esri Land Cover. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Xue, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, W.; Chen, H.; Jia, W.; Zhao, J. Assessment of Fine-Resolution Land Cover Mapping Products in the Changbai Mountain Range, China. All Earth 2024, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. USGS EROS Archive—Digital Elevation—Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 1 Arc-Second Global 2017. USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radar-topography-mission-srtm-1 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Da F. Costa, L. Further Generalizations of the Jaccard Index. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.09619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, L.; Xue, J.; Li, Y. Semantic Segmentation of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images Using Fully Convolutional Network with Adaptive Threshold. Connect. Sci. 2019, 31, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, S.; Saeedi, P. Cloud and Cloud Shadow Segmentation for Remote Sensing Imagery via Filtered Jaccard Loss Function and Parametric Augmentation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 4254–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, A.; Siddique, M.A.; Bhatti, M.K.; Sarfraz, M.S. Comparison of CNNs and Vision Transformers-Based Hybrid Models Using Gradient Profile Loss for Classification of Oil Spills in SAR Images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Xie, J.; Zhu, R. Unsupervised Remote Sensing Image Classification with Differentiable Feature Clustering by Coupled Transformer. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 026505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starovoitov, V.V.; Golub, Y.I. Comparative study of quality estimation of binary classification. Informatics 2020, 17, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Li, H.; Huang, C. Accuracy Evaluation and Consistency Analysis of Four Global Land Cover Products in the Arctic Region. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, J. Uncertainty Analysis of Multisource Land Cover Products in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, W. Comparison between GF-1 and Landsat-8 images in land cover classification. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 35, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Liu, L. Comprehensive Assessment of Nine Fine-Resolution Global Forest Cover Products in the Three-North Shelter Forest Program Region. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Liu, J.; Shi, M.; He, P.; Li, P.; Liu, D. Seasonal Scale Climatic Factors on Grassland Phenology in Arid and Semi-Arid Zones. Land 2024, 13, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Li, H.; Hu, H.; Wang, X. Classification of Alpine Grasslands in Cold and High Altitudes Based on Multispectral Landsat-8 Images: A Case Study in Sanjiangyuan National Park, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Ogaya, R.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Pugh, T.A.M.; Peñuelas, J. Increasing Climatic Sensitivity of Global Grassland Vegetation Biomass and Species Diversity Correlates with Water Availability. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1761–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Xu, J.; Okuto, E.; Luedeling, E. Seasonal Response of Grasslands to Climate Change on the Tibetan Plateau. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Jiménez, R.; Romero-Calcerrada, R.; Ramos-Bernal, R.N.; Arrogante-Funes, P.; Novillo, C.J. Topographic Correction to Landsat Imagery through Slope Classification by Applying the SCS + C Method in Mountainous Forest Areas. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Yang, M.; Wang, F. Land Use and Land Cover Mapping in China Using Multimodal Fine-Grained Dual Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4405219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xu, E. Fusion and Correction of Multi-Source Land Cover Products Based on Spatial Detection and Uncertainty Reasoning Methods in Central Asia. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Satellites | Resolution | Period | Institution | Classification System | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLC_FCS30 | Landsat | 30 m | 1985–2022 | AIR | 35 classes of the fine system | Random forest |

| GlobeLand30 | Landsat TM/ETM+, | 30 m | 2000, 2010, 2020 | NGCC | 10 classes | Pixel-bject–Knowledge (POK) |

| HJ-1, | ||||||

| GF-1 WFV | ||||||

| FROM_GLC10 | Sentinel-2 | 10 m | 2017 | THU | 10 classes | Random forest |

| ESA | Sentinel-1/2 | 10 m | 2020, 2021 | ESA | 11 classes of LCCS | Gradient boosting decision tree (CatBoost) |

| ESRI | Sentinel-2 | 10 m | 2017–2024 | Esri&Impact Observatory | 9 classes | Convolutional Neural Network—UNet |

| Dynamic World | Sentinel-2 | 10 m | Near Real-Time | Google&WRI | 9 classes of probability maps | Fully Convolutional Neural Network (FCNN) |

| Dataset | Class | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLC_FCS30 | Grassland | 130 | Herbaceous cover percentage classification to >15%. |

| GlobeLand30 | Grassland | 30 | Land covered by natural herbaceous vegetation with a cover of more than 10%, including grasslands, meadows, savannas, desert grasslands, and urban artificial grasslands. |

| FROM_GLC10 | Grassland | 30 | Herbaceous cover percentage classification to >15%. |

| Pastures | 31 | Grasslands for grazing. | |

| Other grasslands | 32 | Natural grasslands identifiable. | |

| ESA | Grassland | 30 | Any geographic area dominated by natural herbaceous plant with a cover of 10% or more. Woody plants can be present, assuming their cover is less than 10%. It may also contain uncultivated cropland areas in the reference year. |

| ESRI | Rangeland | 11 | Open areas covered in homogeneous grasses with little to no taller vegetation; Wild cereals and grasses with no obvious human plotting; Mix of small clusters of plants or single plants dispersed on a landscape that shows exposed soil or rock; Scrub-filled clearings within dense forests that are clearly not taller than trees. |

| Dynamic World | Grass | 2 | Open areas covered in homogeneous grasses with little to no taller vegetation. Other homogeneous areas of grass-like vegetation (blade-type leaves) that appear different from trees and shrubland. Wild cereals and grasses with no obvious human plotting. |

| GLC_FCS30 | GlobeLand30 | FROM_GLC10 | ESA | ESRI | Dynamic World | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | 325,669.28 | 311,595.22 | 227,187.42 | 269,262.43 | 322,775.5 | 91,105.19 |

| Proportion (%) | 87.09 | 80.16 | 58.45 | 69.27 | 83.04 | 23.44 |

| OA | PA | UA | F1 | MCC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLC_FCS30 | 68.81% | 95.74% | 66.14% | 0.78 | 0.36 |

| GlobeLand30 | 67.41% | 89.96% | 66.35% | 0.76 | 0.31 |

| FROM_GLC10 | 74.64% | 78.21% | 78.41% | 0.78 | 0.48 |

| ESA | 74.24% | 87.15% | 73.67% | 0.80 | 0.46 |

| ESRI | 69.01% | 94.21% | 66.65% | 0.78 | 0.36 |

| Dynamic World | 57.45% | 34.21% | 83.23% | 0.48 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, M.; He, G.; Wang, G.; Yin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Long, T.; Peng, Y. Spatial Consistency and Accuracy Assessment of Grassland Classification in the Sanjiangyuan Region: From Six Medium Resolution Land Cover Products. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243983

Yuan M, He G, Wang G, Yin R, Zhang Z, Long T, Peng Y. Spatial Consistency and Accuracy Assessment of Grassland Classification in the Sanjiangyuan Region: From Six Medium Resolution Land Cover Products. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243983

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Mingruo, Guojin He, Guizhou Wang, Ranyu Yin, Zhaoming Zhang, Tengfei Long, and Yan Peng. 2025. "Spatial Consistency and Accuracy Assessment of Grassland Classification in the Sanjiangyuan Region: From Six Medium Resolution Land Cover Products" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243983

APA StyleYuan, M., He, G., Wang, G., Yin, R., Zhang, Z., Long, T., & Peng, Y. (2025). Spatial Consistency and Accuracy Assessment of Grassland Classification in the Sanjiangyuan Region: From Six Medium Resolution Land Cover Products. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243983