Evaluating Global and National Datasets in an Ensemble Approach to Estimating Carbon Emissions as Part of SERVIR’s CArbon Pilot

Highlights

- An ensemble analysis of 17 biomass and 12 land cover datasets revealed substantial variability in forest loss and carbon stock estimates across Guatemala, Nepal, and Zambia.

- Comparisons with national reference data showed large differences between global and national NFI.

- The results demonstrate that understanding dataset variability is essential for transparent and robust national greenhouse gas reporting under REDD+ frameworks.

- Integrating regional reference data with global Earth Observation products through ensemble methods can improve the reliability of national carbon accounting.

Abstract

1. Introduction

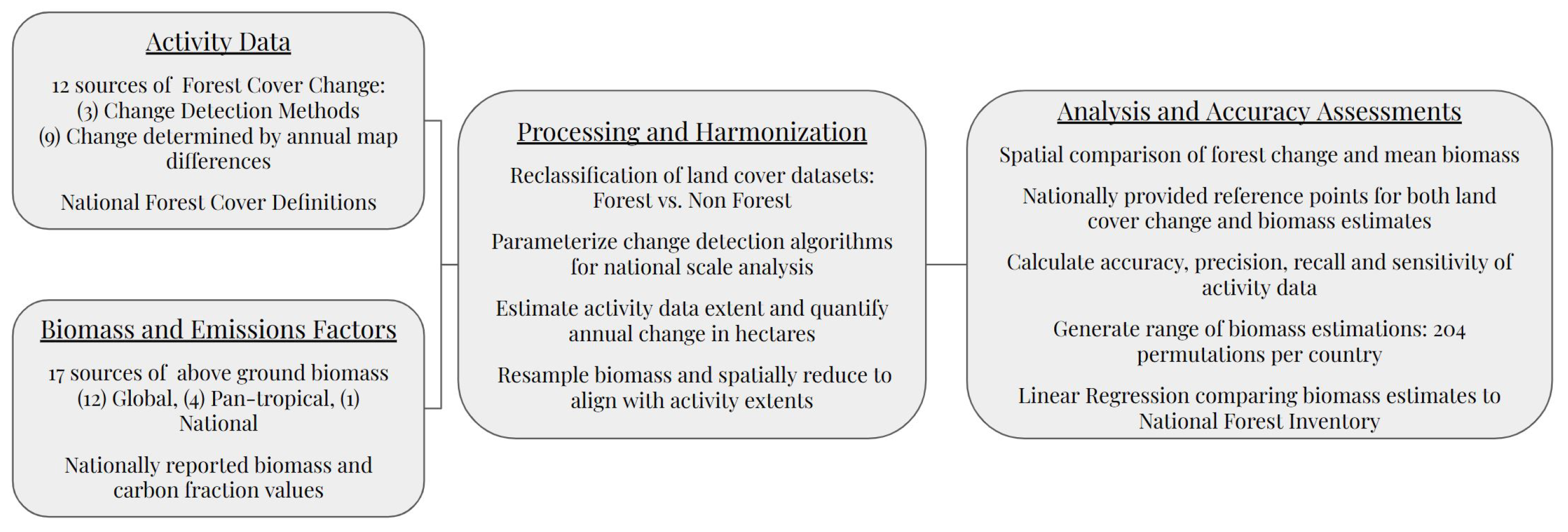

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geographic Domain

Country Reporting

2.2. Activity Data Inputs and Preparation

2.2.1. Pre-Existing Datasets

| Geographic Area | Dataset Source | Dataset Type | Spatial Resolution | Epochs | Reported Accuracy | Dataset Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global/Tropics | Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI)/Impact Observatory [24] | Tree Cover | 10 m | 2017–2021 | 85.0% | Static land cover |

| WorldCover [25,26] | Tree Cover | 10 m | 2020–2022 | 74.4%, 76.7% | Static land cover | |

| Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Forest/Non-Forest Cover (F/NF) [27] | Tree Cover | 25 m | 2007–2021 | 91.0% | Static land cover | |

| Hansen et. al./Global Forest Watch (GFW) [18] | ‘treecover2000’ and ‘lossyear’ | 30 m | 2000–2021 | 94.5% | Static 2000 tree cover and change dataset | |

| ESA CCI Land Cover [28] | Tree Cover | 300 m | 1992–2020 | 75.4% | Static land cover | |

| MODIS MCD12Q1 [29] | Forest Cover | 500 m | 2001–2021 | 73.6% | Static land cover | |

| Guatemala | Mapa de Cobertura Forestal de Guatemala (MAGA) [30,31] | Forest Cover | 30 m | 1991–2020 | 85.0% | Static land cover |

| Nepal | Regional Land Cover Monitoring System (RLCMS) [32,33] | Forest Cover | 30 m | 2000–2021 | 81.7% | Static land cover |

| National Land Cover Monitoring System (NLCMS) [34] | Forest Cover | 30 m | 2000–2019 | 84.8% | Static land cover | |

| Zambia | Regional Centre for Mapping Resource for Development (RCMRD) [35] | Forest Cover | 30 m | 2000–2017 | 68%–74% | Static land cover |

| Parameterized individually for each country: Reference Table 2 | Continuous Change Detection and Classification—Spectral Mixture Analysis (CCDC-SMA) [36] | Change Detection Algorithm | 30 m | 2000–2020 | Variable | Change detection |

| Landsat-based Detection of Trends in Disturbance and Recovery (LandTrendr) [37] | Change Detection Algorithm | 30 m | 2000–2020 | Variable | Change detection |

2.2.2. Change Detection Algorithms

2.2.3. Reference Data Sources and Preparation

2.3. Aboveground Biomass Data and Processing

Assessment of Biomass Products

3. Results

3.1. Forest Cover and Change

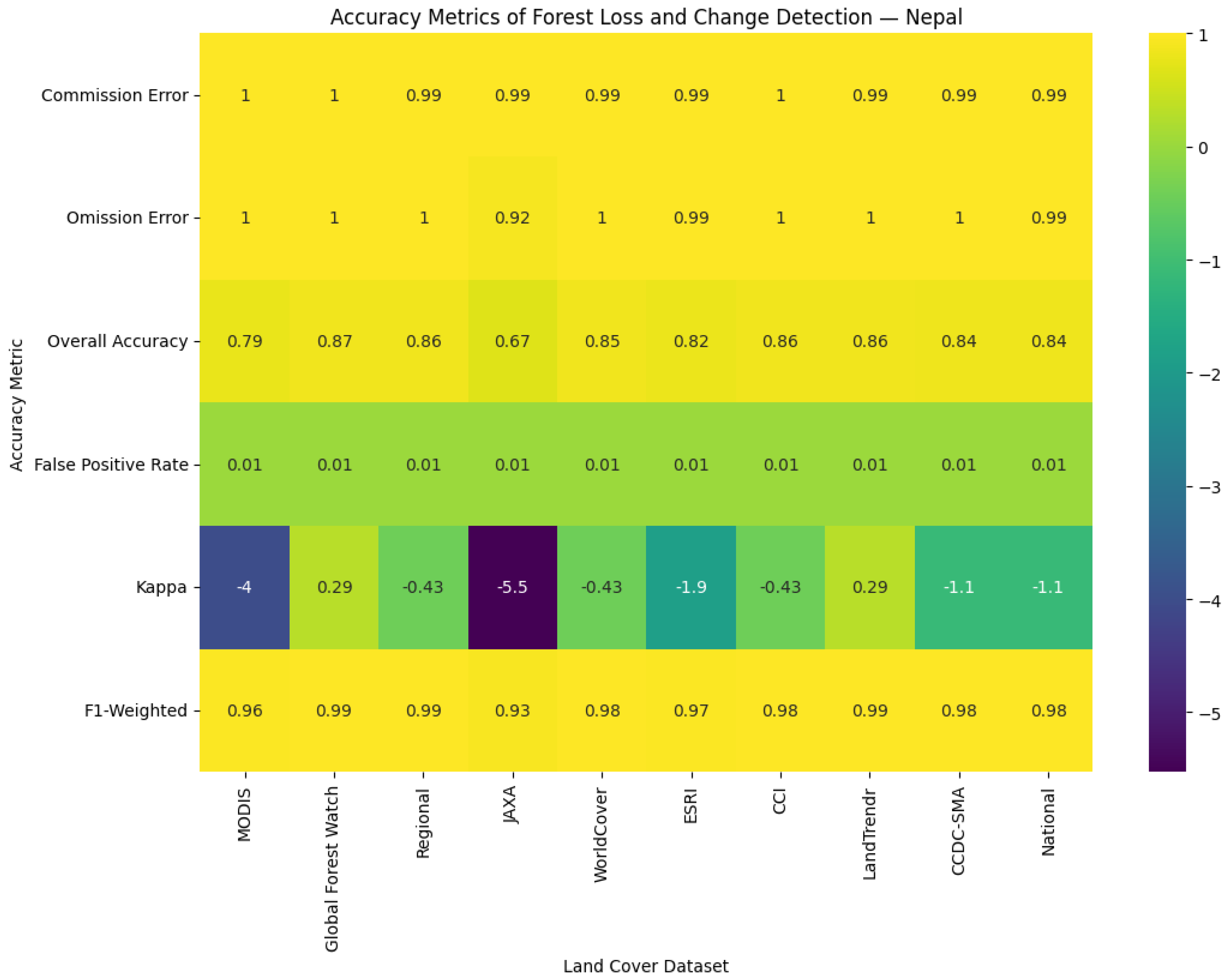

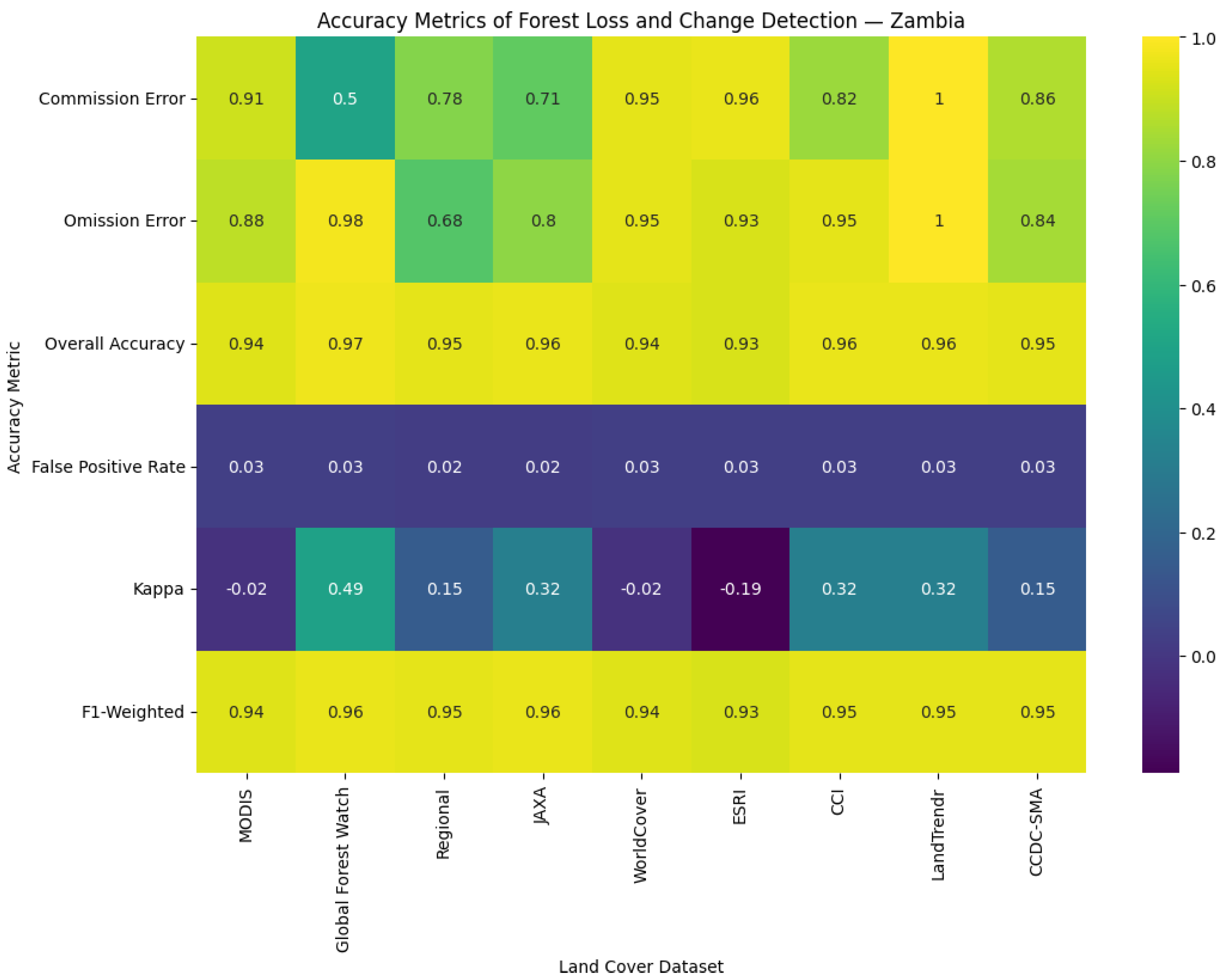

Accuracy Assessment of Activity Data

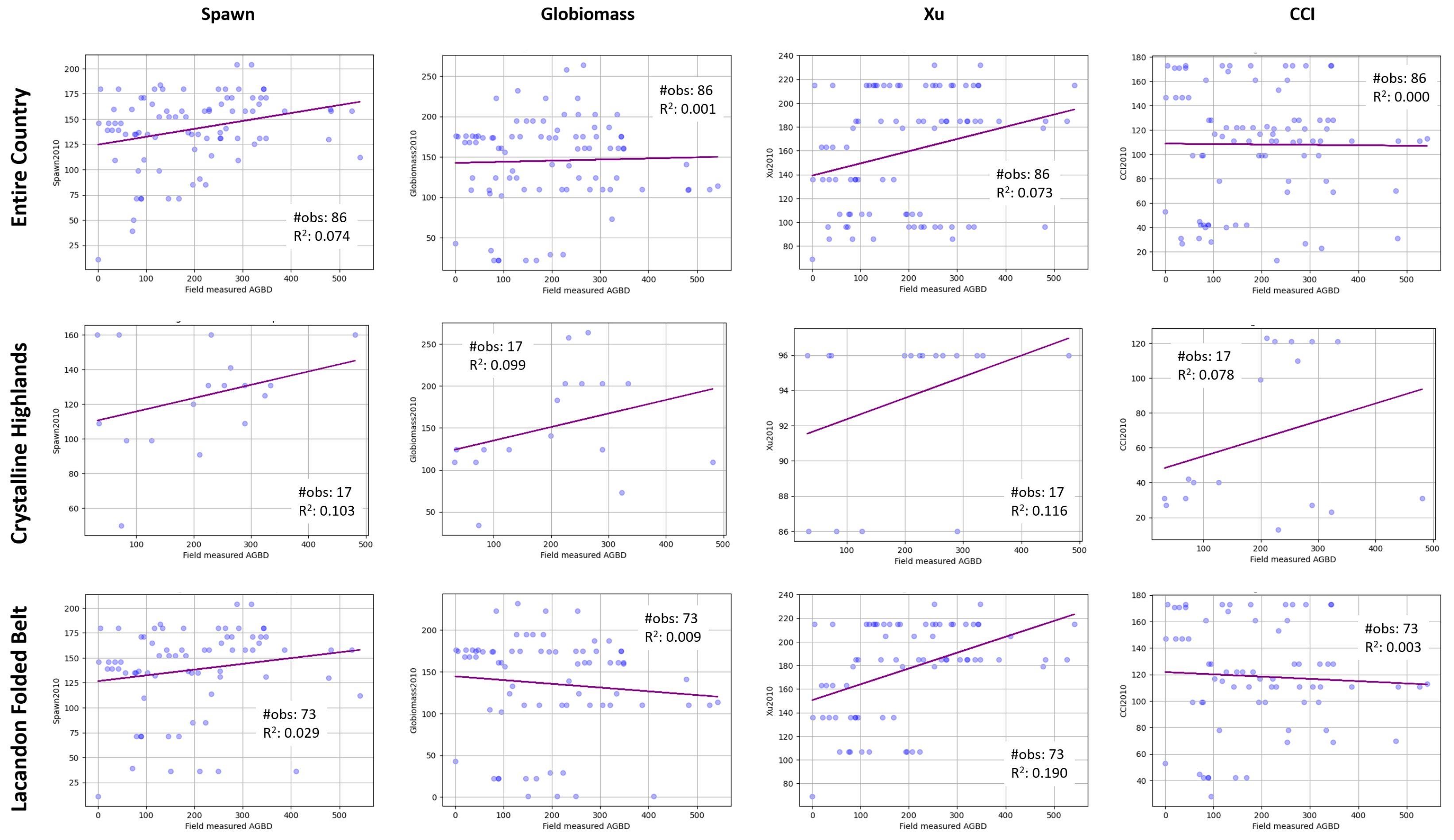

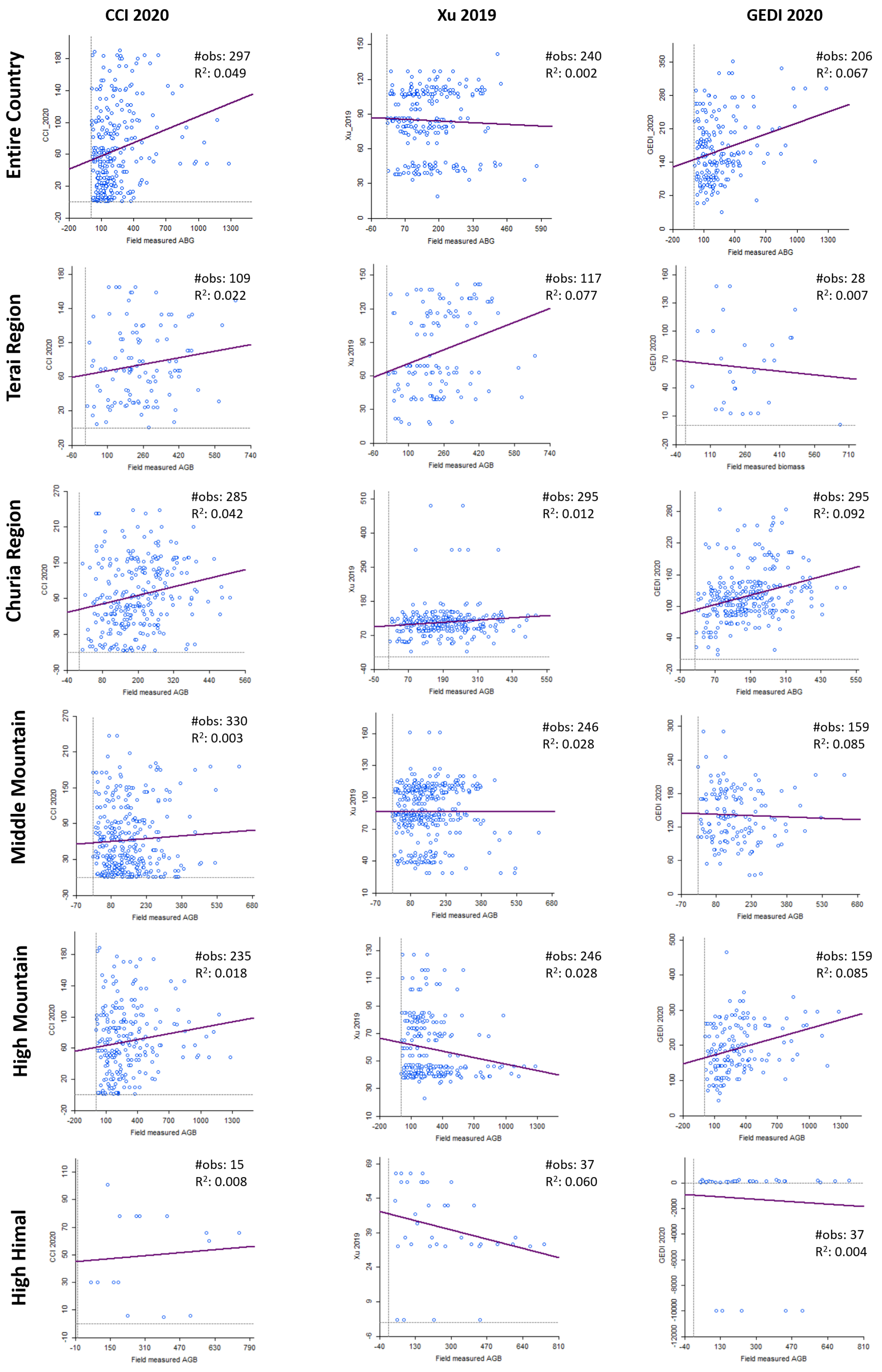

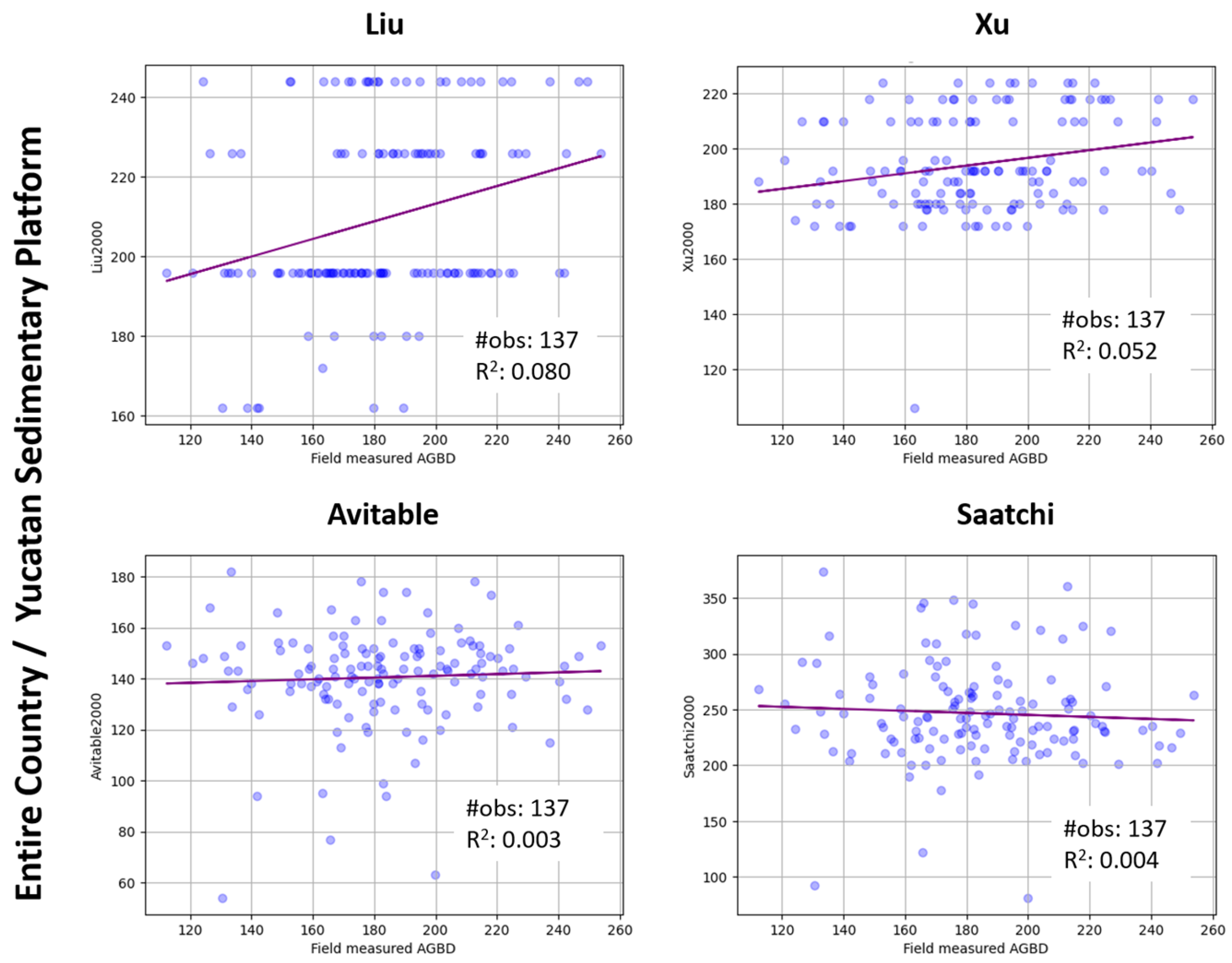

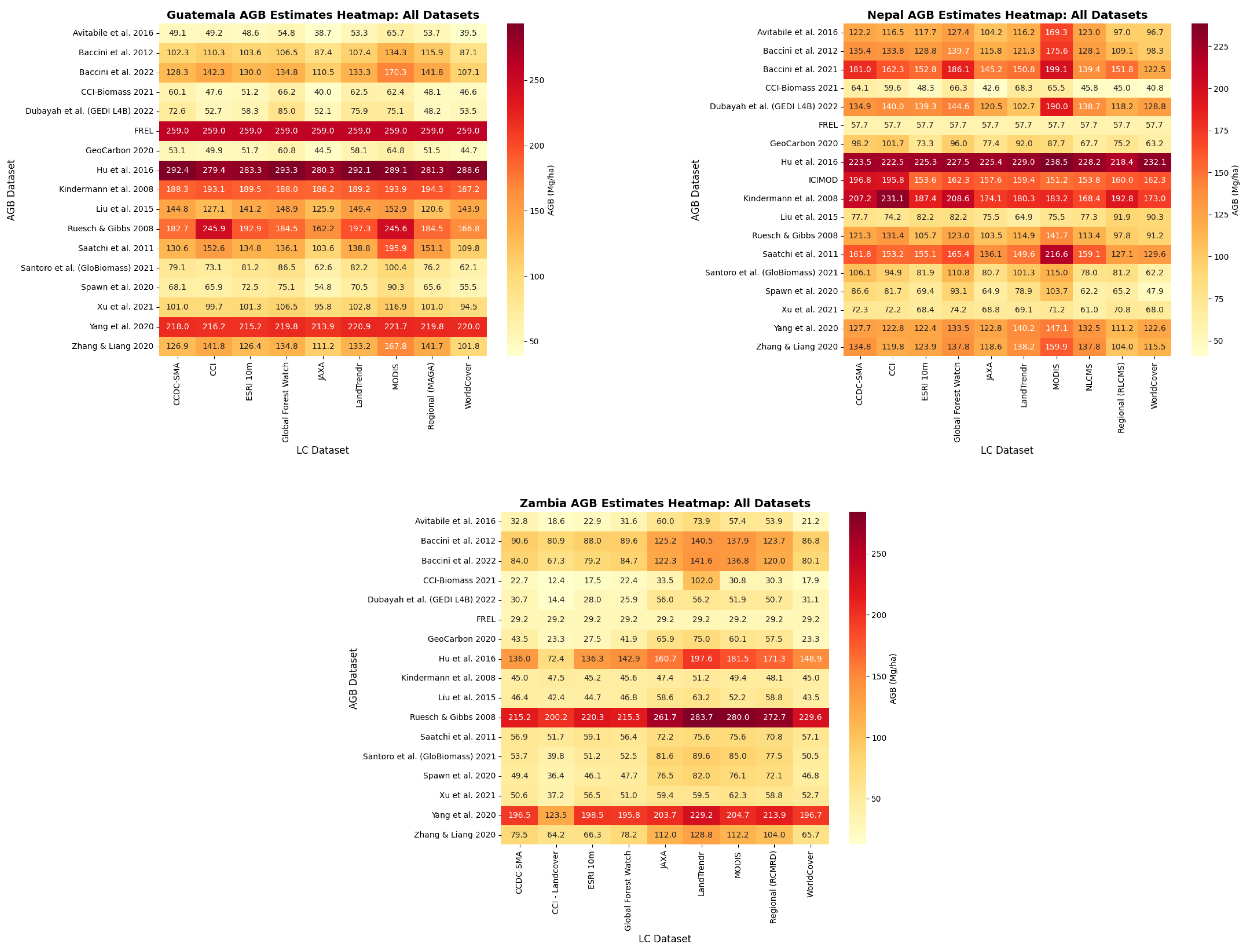

3.2. Biomass

3.2.1. Assessment of Biomass Data

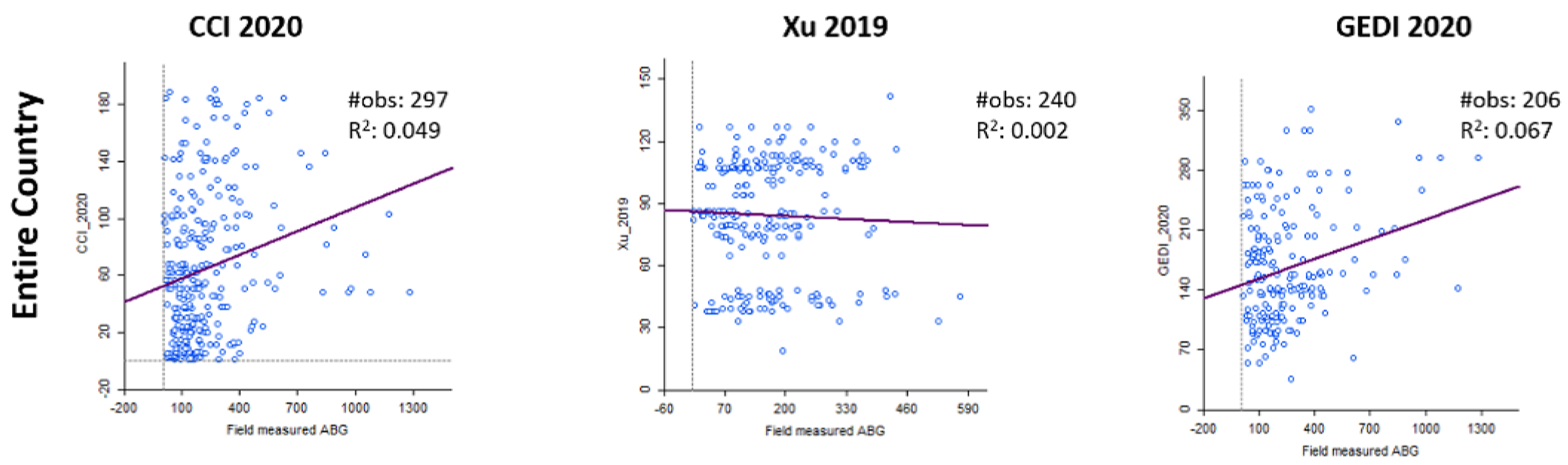

3.2.2. Additional GEDI Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Activity Data

4.2. Biomass Assessments

4.3. Limitations

5. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGB | Aboveground biomass |

| AGC | Aboveground carbon |

| CCDC-SMA | Continuous Change Detection and Classification—Spectral Mixture Analysis |

| CCI | Climate Change Initiative |

| CEO | Collect Earth Online |

| CF | Dry Carbon Fraction |

| EO | Earth Observation |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| ESRI | Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. |

| FRLs | Forest Reference Levels |

| GEDI | Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GFW | Global Forest Watch |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| ICIMOD | International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development |

| IPCC | International Panel on Climate Change |

| LandTrendr | Landsat-based Detection of Trendrs in Disturbance and Recovery |

| MAGA | Mapa de Cobertura Forestal de Guatemala |

| MODIS | Modersate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NLCMS | National Land Cover Monitoring System |

| RCMRD | Regional Centre for Mapping Resouce for Development |

| REDD+ | Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation |

| RLCMS | Regional Land Cover Monitoring System |

| S-CAP | SERVIR CArbon Pilot |

| UNFCCC | United National Framework on Climate Change |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

Appendix A. Dataset Reclassification

| Geographic Area | Land Cover Dataset | Classes Used to Determine Forest Cover |

|---|---|---|

| Global/Tropics | ESRI/Impact Observatory | Trees |

| WorldCover | Tree cover | |

| JAXA Forest/Non-Forest Cover | Dense Forest, Non-dense Forest | |

| Global/Tropics | ESA CCI Land cover | Evergreen Tree Cover, Deciduous Tree Cover, Needleleaved Tree Cover, Mixed Tree Cover |

| MODIS MCD12Q1 | Evergreen Needleleaf Forests, Evergreen Broadleaf Forests, Deciduous Needleleaf Forests Deciduous, Broadleaf Forests, Mixed Forests | |

| Guatemala | MAGA | Forests and semi-natural environments |

| Nepal | RLCMS | Forest |

| NLCMS | Forest | |

| Zambia | RCMRD | Forest |

Appendix B. Biomass

References

- Melo, J.; Baker, T.; Nemitz, D.; Quegan, S.; Ziv, G. Satellite-based global maps are rarely used in forest reference levels submitted to the UNFCCC. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 034021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Gitarskiy, M.L. The refinement to the 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. Fundam. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 2, G.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenqvist, A. Earth Observation Support to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change: The Example of REDD+. In Satellite Earth Observations and Their Impact on Society and Policy; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, L.; Armston, J.; Disney, M.; Avitabile, V.; Barbier, N.; Calders, K.; Carter, S.; Chave, J.; Herold, M.; MacBean, N.; et al. Aboveground Woody Biomass Product Validation Good Practices Protocol. Version 1.0; Technical Report; Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS) Working Group on Calibration & Validation (WGCV) Land Product Validation Subgroup: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araza, A.; de Bruin, S.; Herold, M.; Quegan, S.; Labrière, N.; Rodríguez-Vega, P.; Avitabile, V.; Santoro, M.; Willcock, S.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; et al. A comprehensive framework for assessing the accuracy and uncertainty of global above-ground biomass maps. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 272, 112917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrington, E.A.; Evans, C.A.; Limaye, A.S.; Anderson, E.R.; Flores-Anderson, A.I. Reviews and syntheses: One forest carbon model to rule them all? Utilizing ensembles of forest cover and biomass datasets to determine carbon budgets of the world’s forest ecosystems. EGUsphere 2024, 2024, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatchi, S.S.; Harris, N.L.; Brown, S.; Lefsky, M.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; Salas, W.; Zutta, B.R.; Buermann, W.; Lewis, S.L.; Hagen, S.; et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9899–9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, A.G.S.J.; Goetz, S.J.; Walker, W.S.; Laporte, N.T.; Sun, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Hackler, J.; Beck, P.S.A.; Dubayah, R.; Friedl, M.A.; et al. Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitabile, V.; Herold, M.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; Asner, G.P.; Armston, J.; Ashton, P.S.; Banin, L.; Bayol, N.; et al. An integrated pan-tropical biomass map using multiple reference datasets. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1406–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sy, V.; Herold, M.; Achard, F.; Avitabile, V.; Baccini, A.; Carter, S.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Lindquist, E.; Pereira, M.; Verchot, L. Tropical deforestation drivers and associated carbon emission factors derived from remote sensing data. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 94022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, M.; López, J.; Merino, E.; Buñay, G.; Peñafiel, M.; Villa, R.; Santana, J.; Tipán, E. Monitoring Forest Dynamics in the Palmira Area of Ecuador Using the Land Trendr and Continuous Change Detection Algorithms. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2024, 29, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, S.; Ruiz-Benito, P.; Rebollo, P.; Viana-Soto, A.; Mihai, M.C.; García-Martín, A.; Tanase, M. Forest disturbance regimes and trends in continental Spain (1985–2023) using dense Landsat time series. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICIMOD. Regional Land Cover Monitoring System, 2018. Available online: https://geoapps.icimod.org/RLCMS/ (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- ICIMOD. National Landcover Monitoring System for Nepal, 2024. Available online: https://nepal.spatialapps.net/nlcms (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- RCMRD. Eastern and Southern Africa Land Cover Viewer, 2024. Available online: https://www.rcmrd.org/land-cover-viewer (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Vesa, L.; Mukosha, J.; Roberts, W. Open Foris Calc Scripts for ILUA-II Project, 2015. Available online: https://www.openforis.org/tools/ (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ambiente y Recursos Naturales; Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería y Alimentación; Instituto Nacional de Bosque; Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas; EQUIPO TÉCNICO DE LA FAO. Nivel de Referencia de Emisiones/Absorciones Forestales de la Republica de Guatemala, 2022. Available online: https://www.inab.gob.gt/images/dependencias/dccs/Niveles%20de%20Referencia/Niveles%20de%20Referencia%20Forestales_2022.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation; Ministry of Population and Environment; REDD Implementation Center; Department of Forest Research and Survey; Department of Forests; FRL Nepal Technical Team; FAO International Experts. National Forest Reference Level of Nepal (2000–2010), 2017. Available online: https://redd.gov.np/upload/e66443e81e8cc9c4fa5c099a1fb1bb87/files/Nepal-Forest-RL.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Ministry of Green Economy and Environment. Forest Reference Emissions Level (Zambia). 2021. Available online: https://redd.unfccc.int/files/zambia_frel_modified_2021.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Paudel, N.S.; Karki, R. The Context of REDD+ in Nepal: Drivers, Agents and Institutions; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2013; Volume 81. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri, D.; Mwitwa, J.; Ng’andwe, P.; Kanja, K.; Munyaka, J.; Chileshe, F.; Hamazakaza, P.; Kapembwa, S.; Kwenye, J.M. Agricultural expansion into forest reserves in Zambia: A remote sensing approach. Geocarto Int. 2023, 38, 2213203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, K.; Kontgis, C.; Statman-Weil, Z.; Mazzariello, J.C.; Mathis, M.; Brumby, S.P. Global land use/land cover with Sentinel 2 and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 4704–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaga, D.; Van De Kerchove, R.; Daems, D.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Brockmann, C.; Kirches, G.; Wevers, J.; Cartus, O.; Santoro, M.; Fritz, S.; et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2020 v100, 2021. Available online: https://worldcover2020.esa.int/download?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Zanaga, D.; Van De Kerchove, R.; Daems, D.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Brockmann, C.; Kirches, G.; Wevers, J.; Cartus, O.; Santoro, M.; Fritz, S.; et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2021 v200, 2022. Available online: https://worldcover2021.esa.int/download (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Shimada, M.; Itoh, T.; Motooka, T.; Watanabe, M.; Shiraishi, T.; Thapa, R.; Lucas, R. New global forest/non-forest maps from ALOS PALSAR data (2007–2010). Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 155, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESA. Land Cover CCI Product User Guide Version 2; Tech. Rep.; ESA: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Friedl, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D. MODIS/Terra+ Aqua land cover type yearly L3 global 500m SIN grid V061. In NASA EOSDIS Land Process; DAAC: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2022; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Bosques (INAB); Consejo Nacional de Areas Protegidas (CONAP). Estudio de la Cobertura Forestal para el año 2020 y Dinámica de la Cobertura Forestal en el periodo 2016–2020. Available online: https://www.sifgua.org.gt/SIFGUAData/PaginasEstadisticas/Recursos-forestales/Cobertura.aspx (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Universidad Del Valle Instituto Nacional de Bosques (INAB); Consejo Nacional de Areas Protegidas (CONAP). Dinámica de Cobertura Forestal 1991–2001. Available online: https://www.sifgua.org.gt/SIFGUAData/PaginasEstadisticas/Recursos-forestales/Cobertura.aspx (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- ICIMOD. Land Cover of HKH Region [2001–2021]. Available online: https://rds.icimod.org/Home/DataDetail?metadataId=1972511 (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Uddin, K.; Matin, M.A.; Khanal, N.; Maharjan, S.; Bajracharya, B.; Tenneson, K.; Poortinga, A.; Quyen, N.H.; Aryal, R.R.; Saah, D.; et al. Regional Land Cover Monitoring System for Hindu Kush Himalaya. In Earth Observation Science and Applications for Risk Reduction and Enhanced Resilience in Hindu Kush Himalaya Region: A Decade of Experience from SERVIR; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Research and Training Centre (FRTC). National Land Cover Monitoring System of Nepal. Available online: https://rds.icimod.org/Home/DataDetail?metadataId=1972729 (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- RCMRD SERVIR Eastern Southern Africa; The Government of Zambia. Zambia Landcover Scheme I. Available online: https://maps.rcmrd.org/arcgis/rest/services/Zambia/Zambia_Landcover_2000_Scheme_II/ImageServer (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Chen, S.; Woodcock, C.E.; Bullock, E.L.; Arévalo, P.; Torchinava, P.; Peng, S.; Olofsson, P. Monitoring temperate forest degradation on Google Earth Engine using Landsat time series analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.; Gorelick, N.; Braaten, J.; Cavalcante, L.; Cohen, W.B.; Healey, S. Implementation of the LandTrendr algorithm on google earth engine. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, V.J.; Arévalo, P.; Bratley, K.H.; Bullock, E.L.; Gorelick, N.; Yang, Z.; Kennedy, R.E. Demystifying LandTrendr and CCDC temporal segmentation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 110, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, G.; McCallum, I.; Fritz, S.; Obersteiner, M. A global forest growing stock, biomass and carbon map based on FAO statistics. Silva Fenn. 2008, 42, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.K.; Ruesch, A. New IPCC Tier-1 Global Biomass Carbon Map for the Year 2000; 2008. Available online: https://data.ess-dive.lbl.gov/datasets/doi:10.15485/1463800 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Xu, L.; Saatchi, S.S.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Pongratz, J.; Bloom, A.A.; Bowman, K.; Worden, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, Y.; et al. Changes in global terrestrial live biomass over the 21st century. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M. CCI-Biomass: Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, Version 4.0; 2013; Available online: https://climate.esa.int/media/documents/D2_2_Algorithm_Theoretical_Basis_Document_ATBD_V4.0_20230317.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Liu, Y.Y.; Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; De Jeu, R.A.M.; Canadell, J.G.; McCabe, M.F.; Evans, J.P.; Wang, G. Recent reversal in loss of global terrestrial biomass. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, A.; Walker, W.; Carvahlo, L.; Farina, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D. Aboveground Live Woody Biomass Density. 2021. Available online: https://data.globalforestwatch.org/datasets/gfw::aboveground-live-woody-biomass-density/about (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Hu, T.; Su, Y.; Xue, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Fang, J.; Guo, Q. Mapping global forest aboveground biomass with spaceborne LiDAR, optical imagery, and forest inventory data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.; Beaudoin, A.; Beer, C.; Cartus, O.; Fransson, J.E.S.; Hall, R.J.; Pathe, C.; Schmullius, C.; Schepaschenko, D.; Shvidenko, A.; et al. Forest growing stock volume of the northern hemisphere: Spatially explicit estimates for 2010 derived from Envisat ASAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 168, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spawn, S.A.; Sullivan, C.C.; Lark, T.J.; Gibbs, H.K. Harmonized global maps of above and belowground biomass carbon density in the year 2010. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, S. Fusion of multiple gridded biomass datasets for generating a global forest aboveground biomass map. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M.; Cartus, O.; Carvalhais, N.; Rozendaal, D.; Avitabilie, V.; Araza, A.; De Bruin, S.; Herold, M.; Quegan, S.; Rodríguez Veiga, P.; et al. The global forest above-ground biomass pool for 2010 estimated from high-resolution satellite observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2020, 2020, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Y. A new method for generating a global forest aboveground biomass map from multiple high-level satellite products and ancillary information. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubayah, R.O.; Armston, J.; Healey, S.P.; Yang, Z.; Patterson, P.L.; Saarela, S.; Stahl, G.; Duncanson, L.; Kellner, J.R. GEDI L4B Gridded Aboveground Biomass Density, Version 2. ORNL DAAC 2022. Available online: https://daac.ornl.gov/GEDI/guides/GEDI_L4B_Gridded_Biomass.html (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- ICIMOD. Above Ground Biomass (AGB) Data in Nepal.R 2015. Available online: https://rds.icimod.org/Home/DataDetail?metadataId=23172 (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Shriar, A.J. Food security and land use deforestation in northern Guatemala. Food Policy 2002, 27, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, J.A.; Currit, N.; Reygadas, Y.; Liller, L.I.; Allen, G. Drug trafficking, cattle ranching and Land use and Land cover change in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, E.L.; Nolte, C.; Reboredo Segovia, A.L.; Woodcock, C.E. Ongoing forest disturbance in Guatemala’s protected areas. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 6, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environment of Zambia Ministry of Tourism and Natural Resources. Integrated Land Use Assessment (ILUA) II, 2013. Available online: https://www.woodwellclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Wamunyima_ILUA.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Paudel, B.; Zhang, Y.l.; Li, S.C.; Liu, L.S.; Wu, X.; Khanal, N.R. Review of studies on land use and land cover change in Nepal. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, N.; Matin, M.A.; Uddin, K.; Poortinga, A.; Chishtie, F.; Tenneson, K.; Saah, D. A comparison of three temporal smoothing algorithms to improve land cover classification: A case study from NEPAL. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.L.; Sah, R.N. Structure and diversity of natural and managed sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.) forest in the Terai of Nepal. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 176, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, O.; Parajuli, R.; Kharel, G.; Poudyal, N.; Taylor, E. Stakeholder opinions on scientific forest management policy implementation in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Masri, B.; Xiao, J. Comparison of Global Aboveground Biomass Estimates From Satellite Observations and Dynamic Global Vegetation Models. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2025, 130, e2024JG008305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, L.; Kellner, J.R.; Armston, J.; Dubayah, R.; Minor, D.M.; Hancock, S.; Healey, S.P.; Patterson, P.L.; Saarela, S.; Marselis, S.; et al. Aboveground biomass density models for NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) lidar mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, S.; Armston, J.; Hofton, M.; Sun, X.; Tang, H.; Duncanson, L.; Kellner, J.R.; Dubayah, R. The GEDI simulator: A large-footprint waveform lidar simulator for calibration and validation of spaceborne missions. Earth Space Sci. 2019, 6, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsendbazar, N.E.; Li, L.; Koopman, M.; Carter, S.; Herold, M.; Georgieva, I.; Lesiv, M. Product Validation Report (D12-PVR) v1.1: ESA WorldCover; Version 1.1; Technical Report; ESA WorldCover Consortium/IIASA: Laxenburg, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M.C.; Pickens, A.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Turubanova, S.; Zalles, V.; Li, X.; Khan, A.; Stolle, F.; et al. The Global 2000–2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset Derived from the Landsat Archive: First Results. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 856903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Hanan, N.P.; Yu, Q.; Gilani, H. Enhancing GEDI aboveground biomass density estimates in contrasting forests of Pakistan. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 587, 122747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SERVIR Science Coordination Office. SERVIR CArbon Pilot. Available online: https://s-cap.servirglobal.net/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

| CCDC-SMA (2000–2020) [36] | LandTrendr (2000–2020) [37] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | H | N | L | Parameters | H | N | L |

| Forest Mask | R | R | R | Max Segments | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Threshold | 6300 | 2600 | 0 | Spike Threshold | 1 | 0.9 | 0.75 |

| Change Probability | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | Vertex Count Overshoot | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Num of Consec | 5 | 5 | 5 | Prevent One Year Recovery | F | F | F |

| CCDC-SMA performed better when including imagery from the entire year, whereas LandTrendr performed better when only including imagery during the dry season for that region. | Recovery Threshold | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | |||

| pval Threshold | 0.05 | 0.5 | 1 | ||||

| Best Model Proportion | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | ||||

| Min Observations Needed | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| MMU: True | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| Geographic Area | Biomass Data Source | Spatial Resolution | Epochs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Kindermann et al. 2008 [39] | 50 km | 2005 |

| Ruesch and Gibbs 2008 [40] | 1 km | 2000 | |

| Xu et al. 2021 [41] | 10 km | 2000–2019 * | |

| CCI-Biomass 2021 [42] | 100 m | 2010, 2017–2020 * | |

| Liu et al. 2015 [43] | 25 km | 1993–2012 * | |

| Baccini et al. 2021 [44] | 30 m | 2000 | |

| Hu et al. 2016 [45] | 1 km | 2000 | |

| GeoCarbon 2020 [46] | 1 km | 2000 | |

| Spawn et al. 2020 [47] | 250 m | 2010 | |

| Zhang and Liang 2020 [48] | 1 km | 2000 | |

| Santoro et al. (GloBiomass) 2021 [49] | 100 m | 2010 | |

| Yang et al. 2020 [50] | 1 km | 2005 | |

| Pan-tropical | Baccini et al. 2012 [9] | 500 m | 2008 |

| Saatchi et al. 2011 [8] | 1 km | 2000 | |

| Avitabile et al. 2016 [10] | 1 km | 2000 | |

| Dubayah et al. (GEDI, Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation, L4B) 2022 [51] | 1 km | 2017–2020 * | |

| Nepal | ICIMOD [52] | 5 km | 2015 |

| Forest/Tree Cover Source | GTM (ha) | GTM (%) | NPL (ha) | NPL (%) | ZMB (ha) | ZMB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRI | 6,063,840 | 55.68 | 7,527,721 | 51.14 | 42,310,275 | 56.22 |

| WorldCover | 7,160,109 | 65.75 | 8,964,781 | 60.91 | 30,908,700 | 41.07 |

| JAXA F/NF | 5,624,125 | 51.65 | 6,581,404 | 44.72 | 6,509,683 | 8.65 |

| GFW | 6,373,681 | 55.00 | 6,331,639 | 43.02 | 59,738,569 | 79.37 |

| ESA CCI LC | 6,731,937 | 57.23 | 8,569,636 | 58.23 | 24,835,162 | 33.00 |

| MODIS MCD12Q1 | 3,735,729 | 34.30 | 4,156,325 | 28.24 | 8,863,944 | 11.77 |

| Regional GTM: n/a, NPL: RLCMS, ZMB: RCMRD | - | - | 7,252,713 | 49.28 | - | - |

| National GTM: MAGA, NPL: NLCMS, ZMB: n/a | 2,917,000 | 34.33 | 7,053,215 | 47.92 | - | - |

| Region | Overlapping Pts | GEDI Pts | NFI Pts | R2 | rRMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinturon Plegado Del Lacandon | 69 | 49,881 | 96 | 0.042 | 88.49% |

| Crystalline Highlands | 58 | 35,333 | 319 | 0.088 | 101.37% |

| Izabal Depression | 14 | 4298 | 29 | 0.113 | 50.64% |

| Yucatan Sedimentary Platform | 193 | 79,341 | 669 | 0.007 | 77.62% |

| Volcanic Highlands | 73 | 45,707 | 622 | 0.005 | 96.34% |

| Sedimentary Highlands | 33 | 90,417 | 526 | 0.013 | 129.04% |

| Region | Overlapping Pts | GEDI Pts | NFI Pts | R2 | rRMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinturon Plegado Del Lacandon | 14 | 36,077 | 96 | 0.06 | 256.77% |

| Crystalline Highlands | 8 | 12,993 | 319 | 0.16 | 387.45% |

| Yucatan Sedimentary Platform | 64 | 54,544 | 669 | 0.04 | 373.29% |

| Volcanic Highlands | 15 | 24,890 | 622 | 0.12 | 226.61% |

| Sedimentary Highlands | 5 | 34,126 | 526 | 0.03 | 108.98% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Evans, C.; Cherrington, E.A.; Carey, L.; Limaye, A.; Maharjan, S.; Nuñez, D.I.; Anderson, E.R.; Herndon, K.; Flores-Anderson, A.I. Evaluating Global and National Datasets in an Ensemble Approach to Estimating Carbon Emissions as Part of SERVIR’s CArbon Pilot. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3975. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243975

Evans C, Cherrington EA, Carey L, Limaye A, Maharjan S, Nuñez DI, Anderson ER, Herndon K, Flores-Anderson AI. Evaluating Global and National Datasets in an Ensemble Approach to Estimating Carbon Emissions as Part of SERVIR’s CArbon Pilot. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3975. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243975

Chicago/Turabian StyleEvans, Christine, Emil A. Cherrington, Lauren Carey, Ashutosh Limaye, Sajana Maharjan, Diego Incer Nuñez, Eric R. Anderson, Kelsey Herndon, and Africa I. Flores-Anderson. 2025. "Evaluating Global and National Datasets in an Ensemble Approach to Estimating Carbon Emissions as Part of SERVIR’s CArbon Pilot" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3975. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243975

APA StyleEvans, C., Cherrington, E. A., Carey, L., Limaye, A., Maharjan, S., Nuñez, D. I., Anderson, E. R., Herndon, K., & Flores-Anderson, A. I. (2025). Evaluating Global and National Datasets in an Ensemble Approach to Estimating Carbon Emissions as Part of SERVIR’s CArbon Pilot. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3975. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243975