Assessment of WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS Radiation Estimation in Asia Using the Geostationary Satellite Measurement

Highlights

- The WRF-Solar EPS model shows comparable short-term (<36 h) forecasting capabilities to WRF-Solar, the model performing well in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and the Yangtze River Delta. Bias is lower in summer and autumn, while RMSE and MAE are lower in autumn and winter.

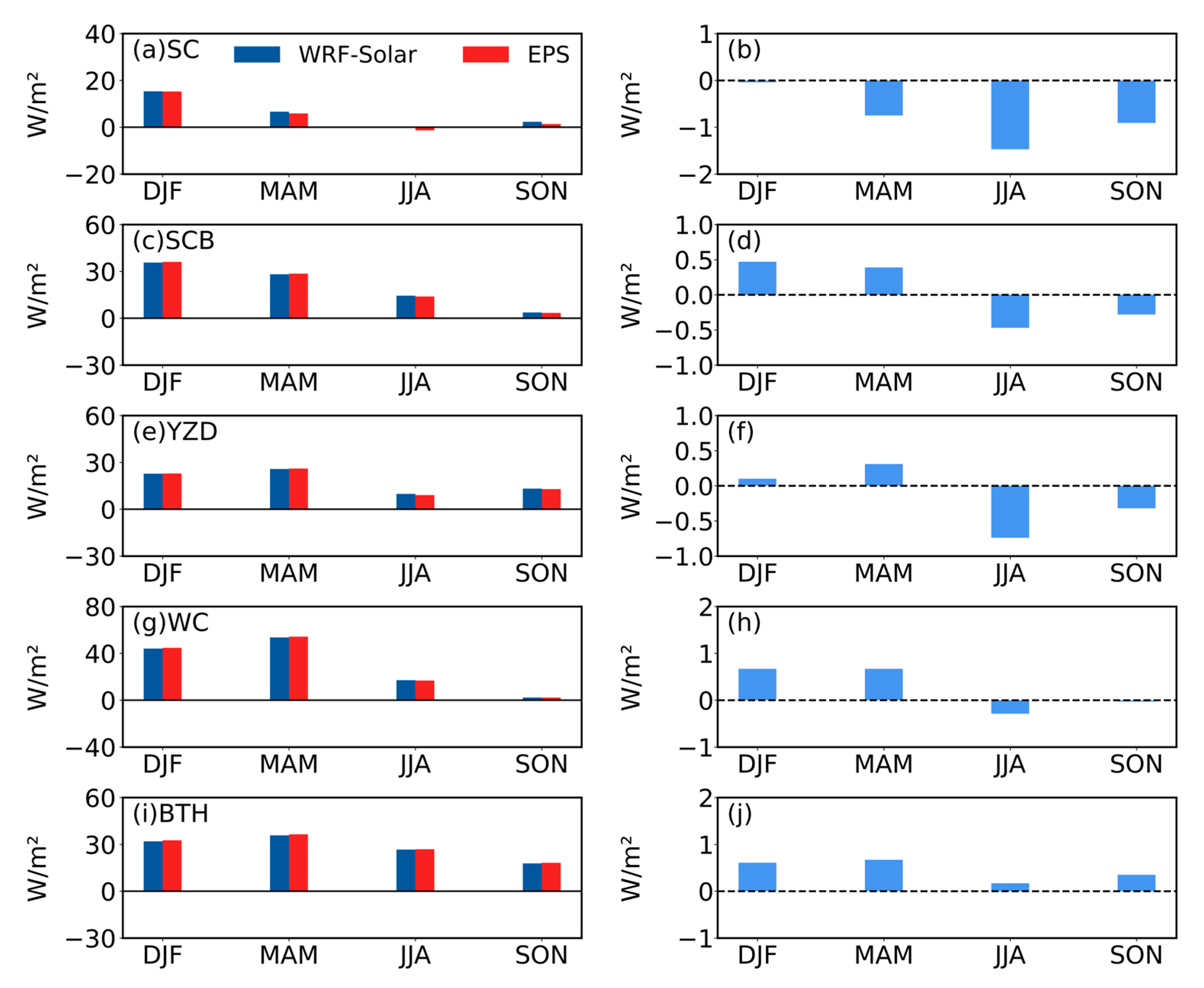

- There is a temporal mismatch in the seasonal fluctuations of the bias, root mean square error, and mean absolute error of GHI. The errors fluctuations in DIR over Western China follow a distinctive pattern.

- Ensemble forecasting can slightly enhance the stability of forecast results, but improve results little in short-term forecasting.

- The error performance of WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS in the short-term prediction of solar irradiance at the interannual scale in Asia is quantitatively evaluated, which provides a basic reference for subsequent improvement work.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Satellite-Derived Solar Radiation Data

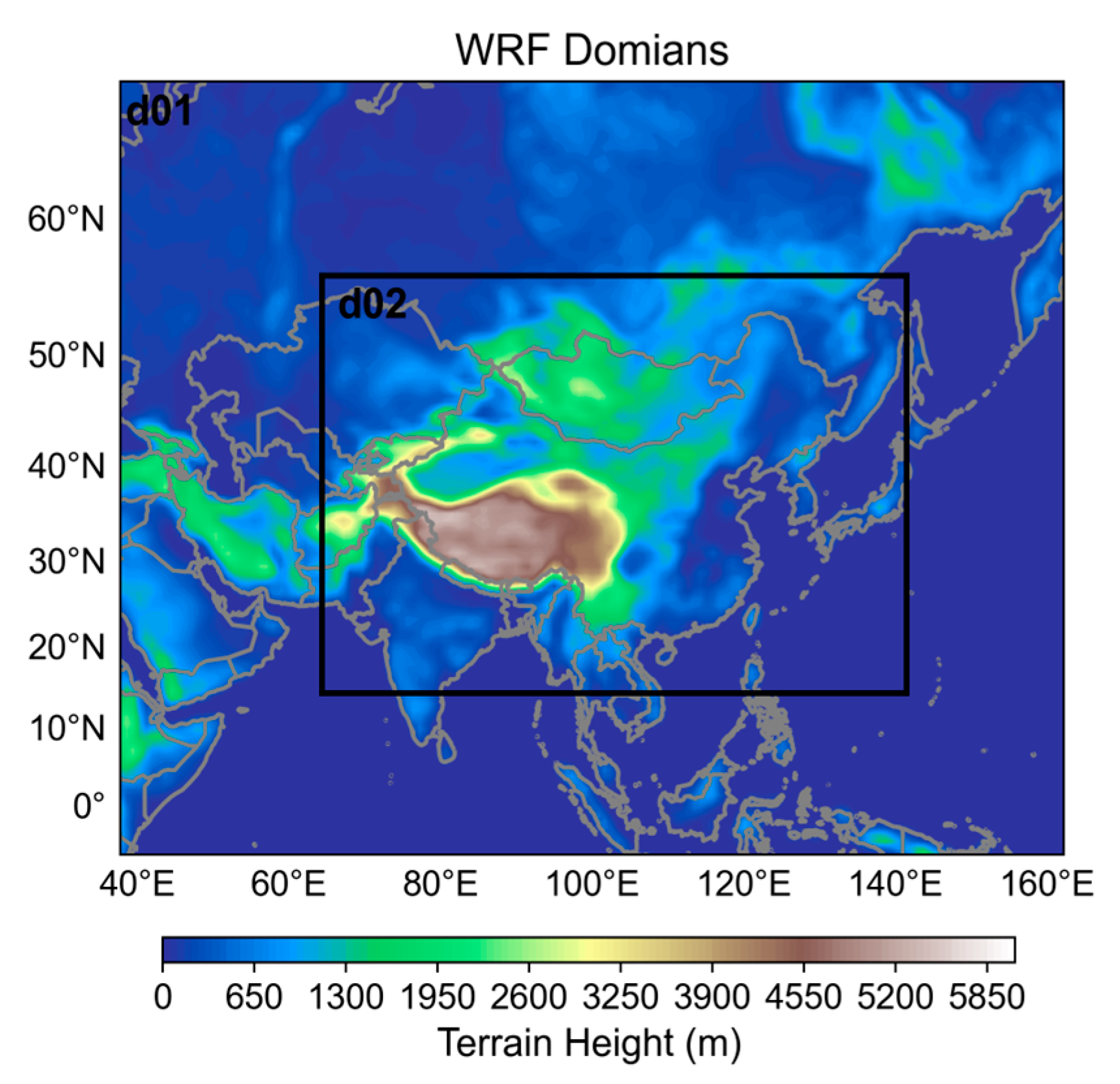

2.2. WRF-Solar Setting

2.3. Statistics Methods

3. Results

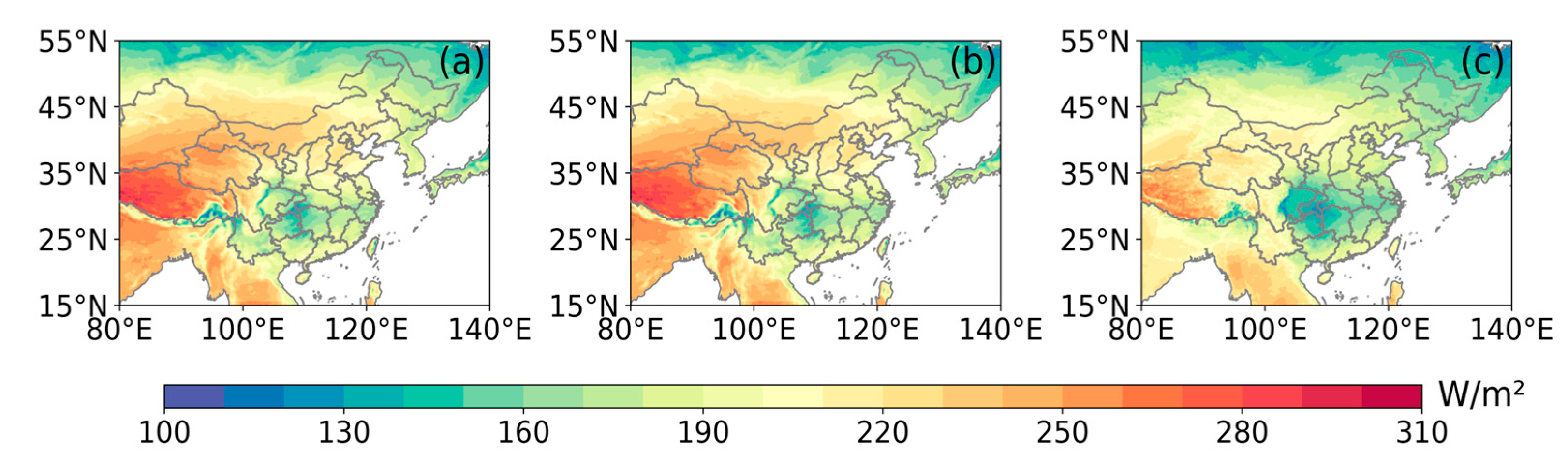

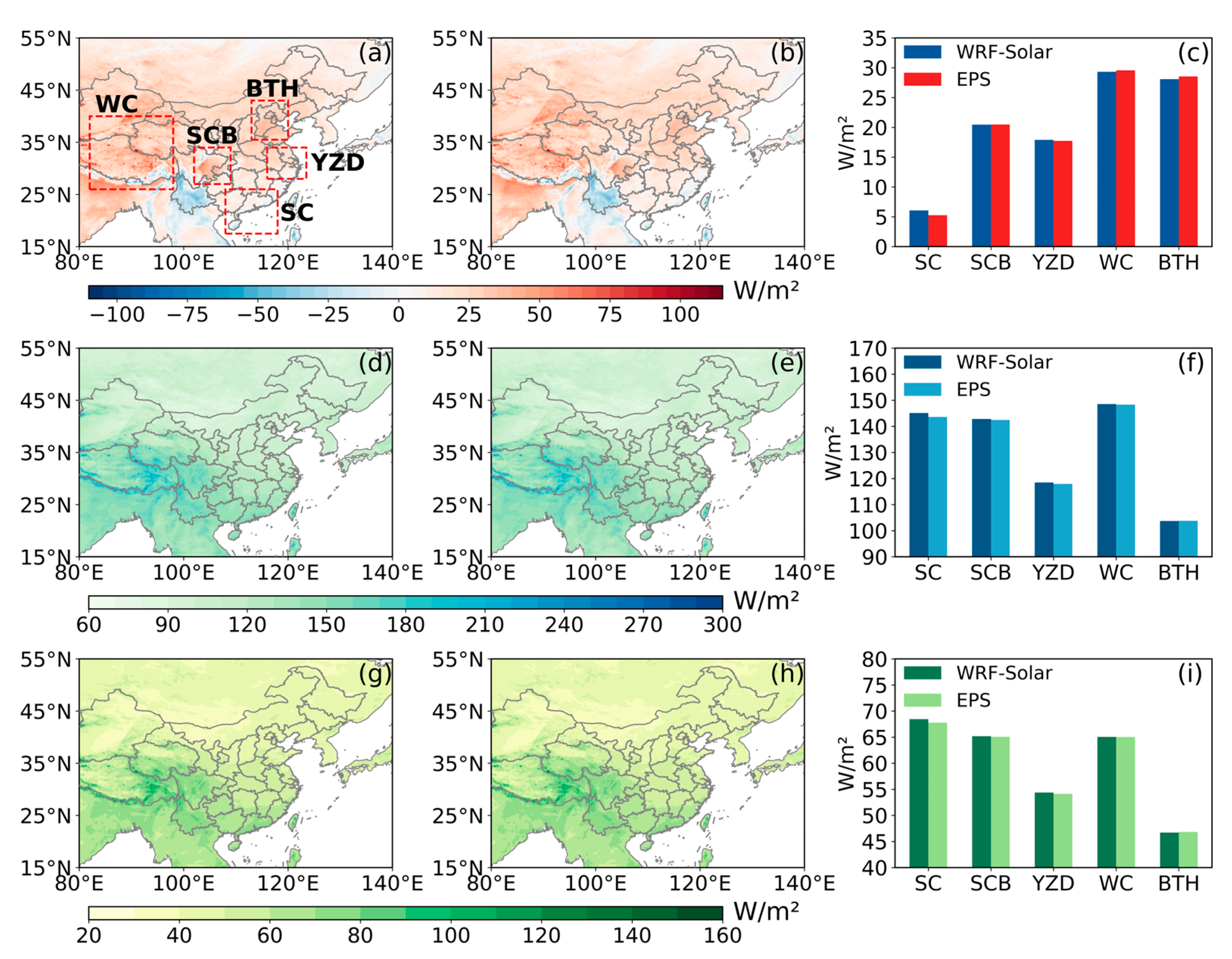

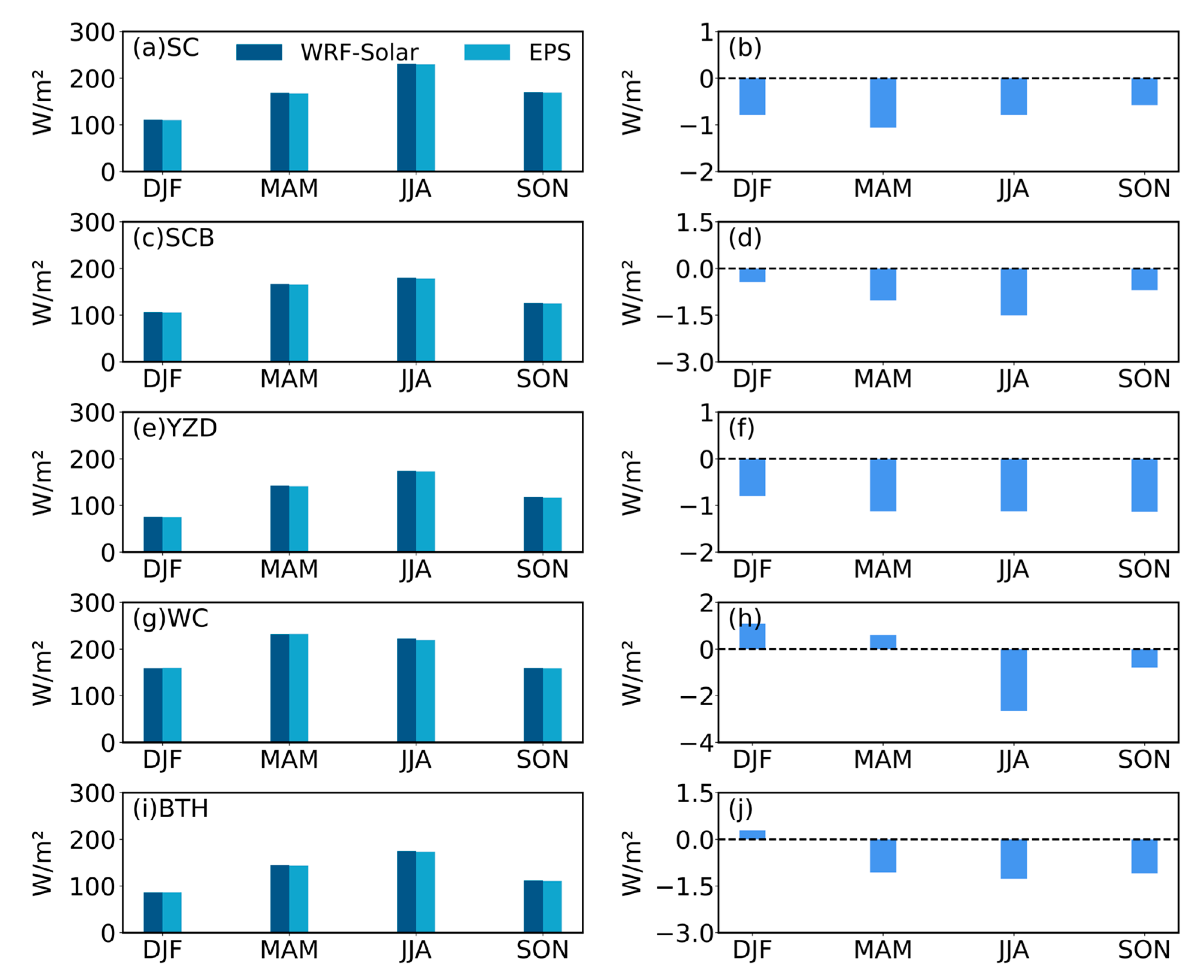

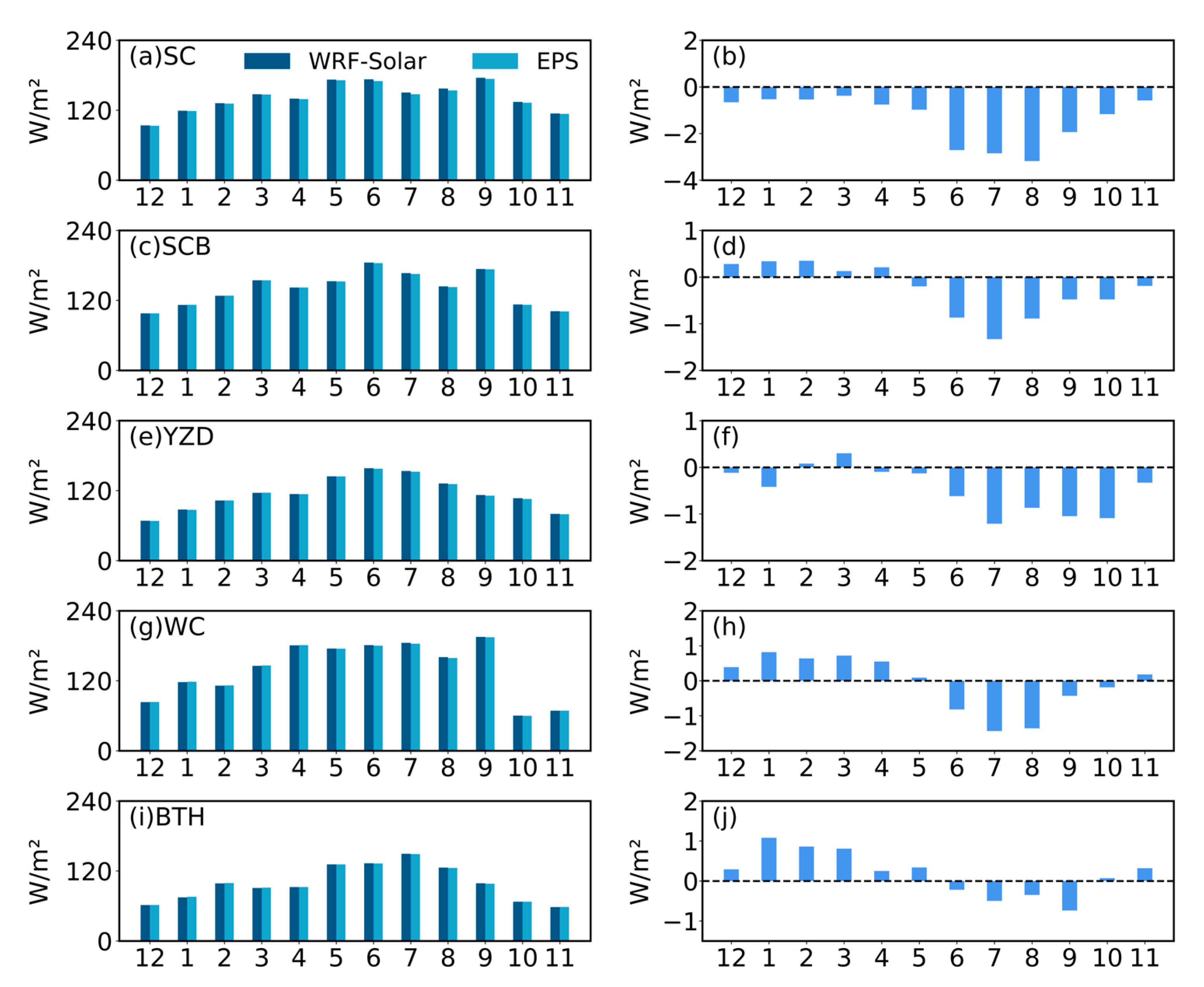

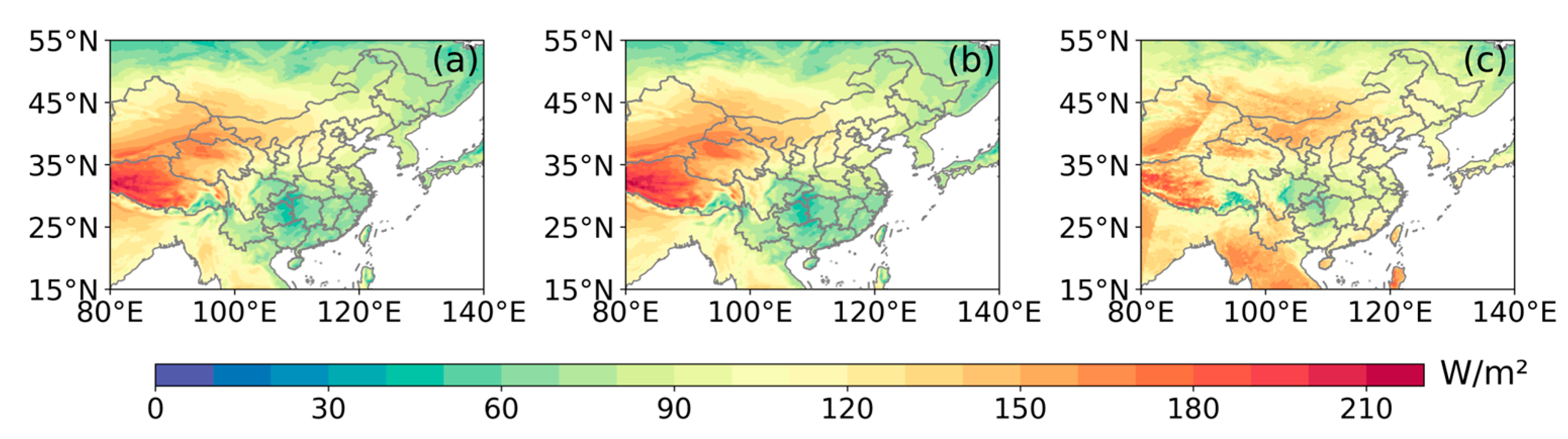

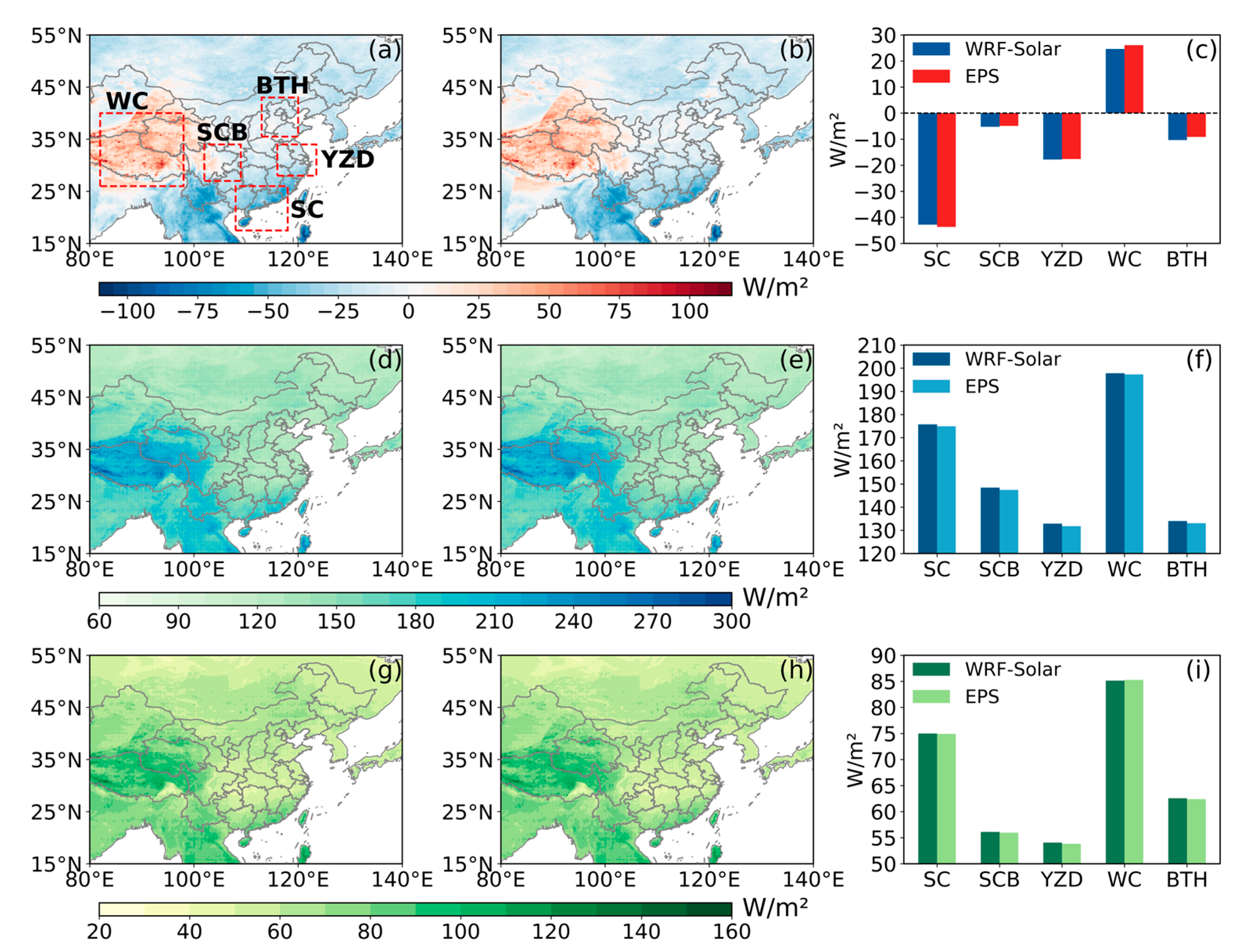

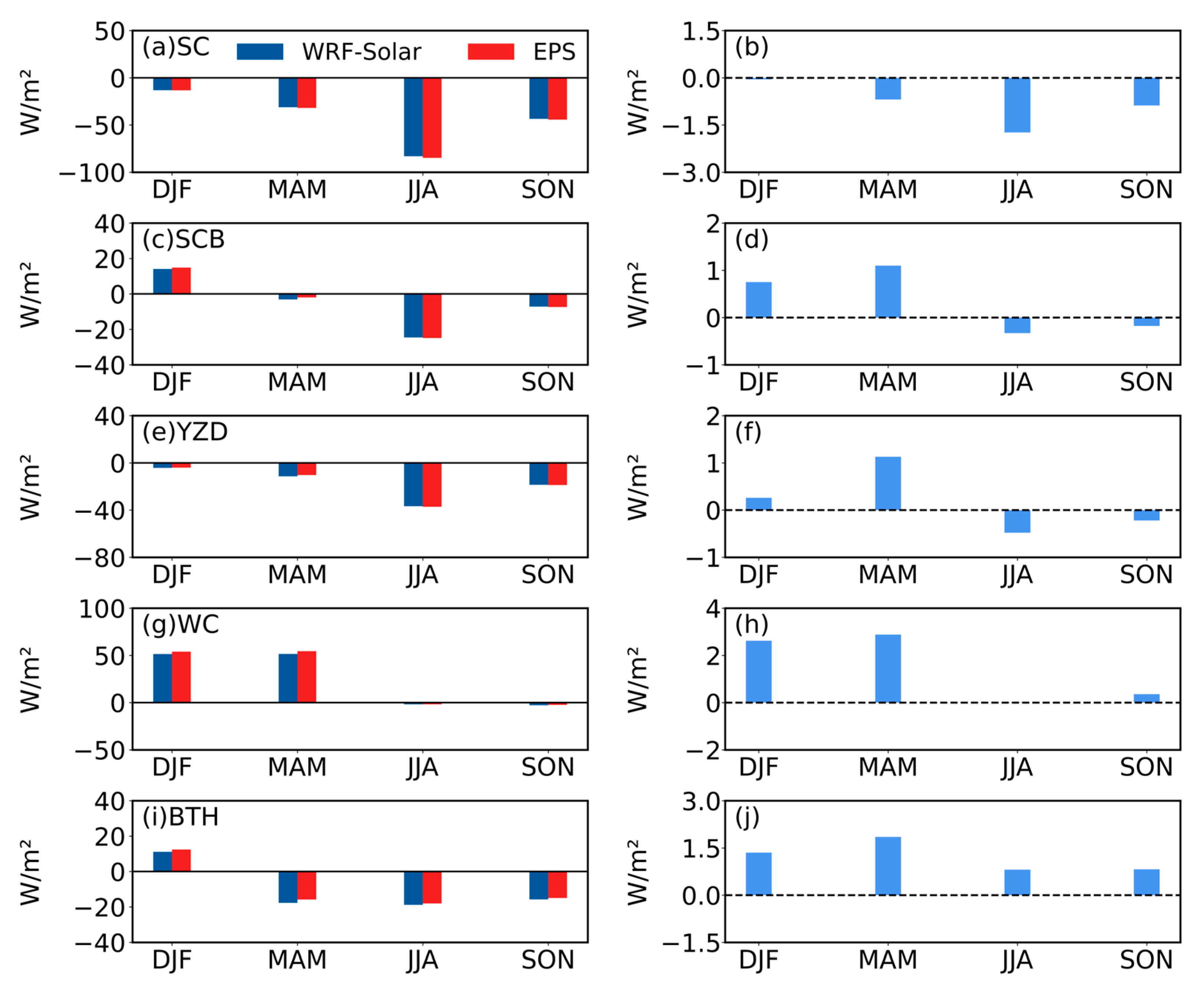

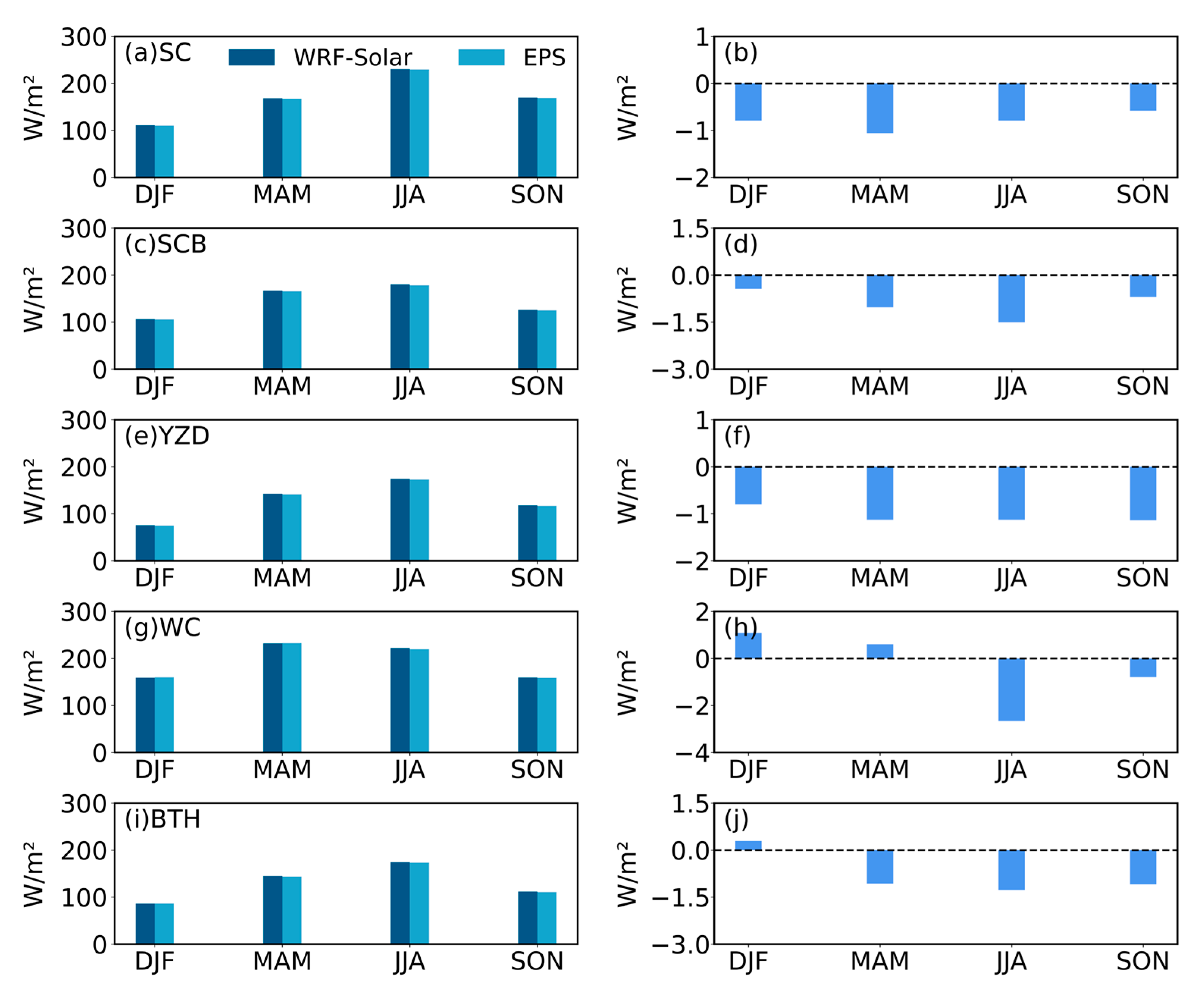

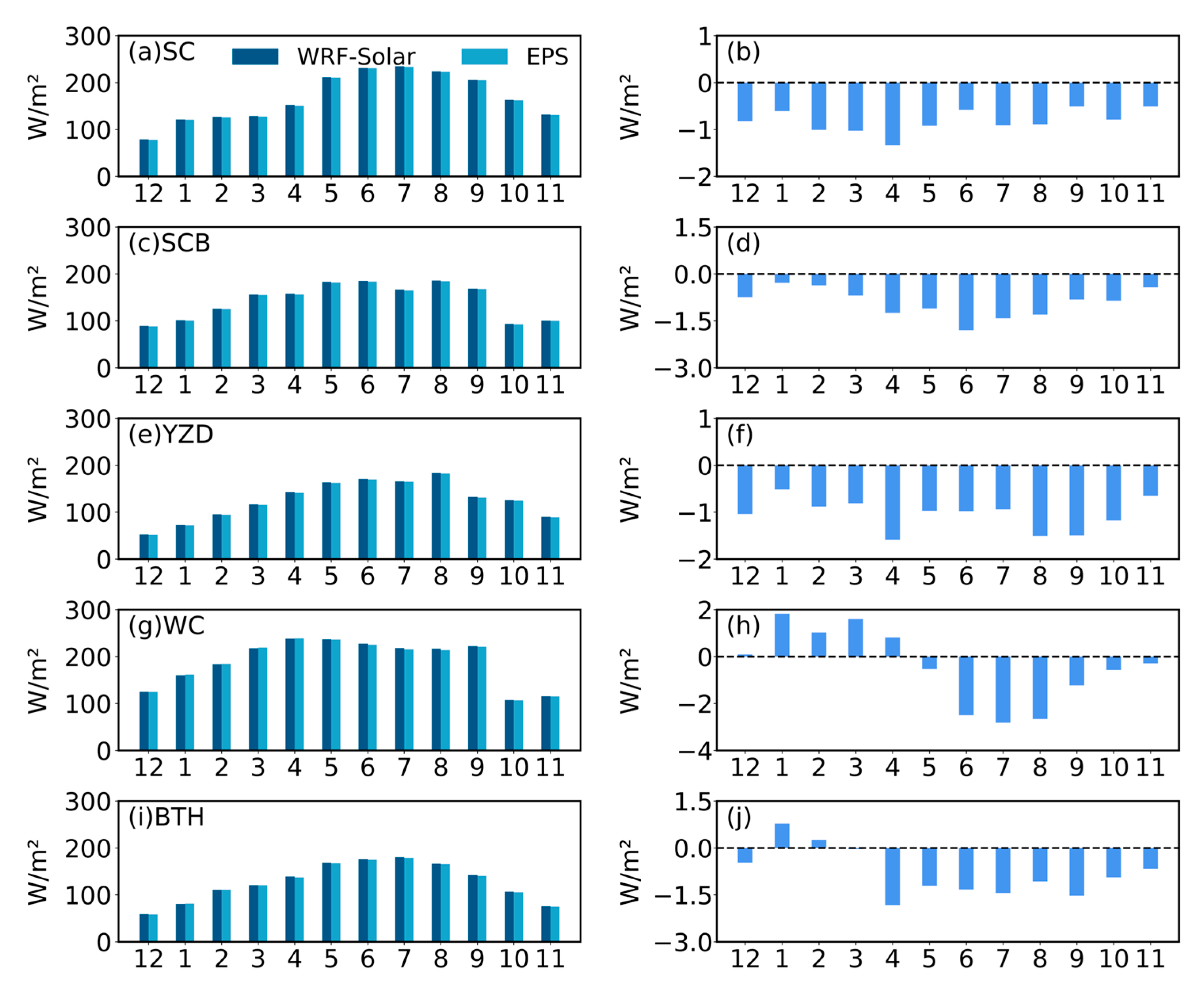

3.1. Assessment of WRF-Solar and EPS GHI Estimation

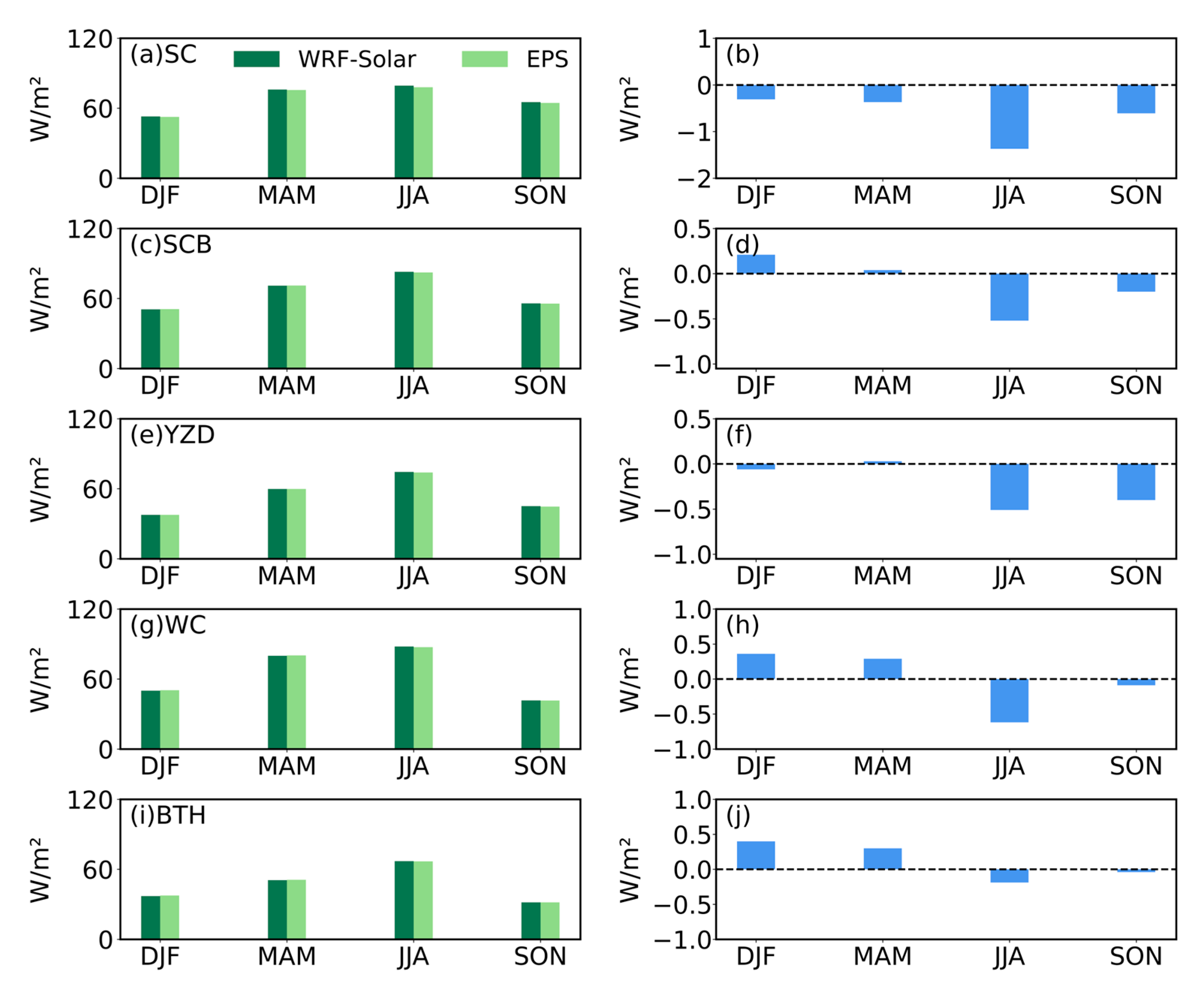

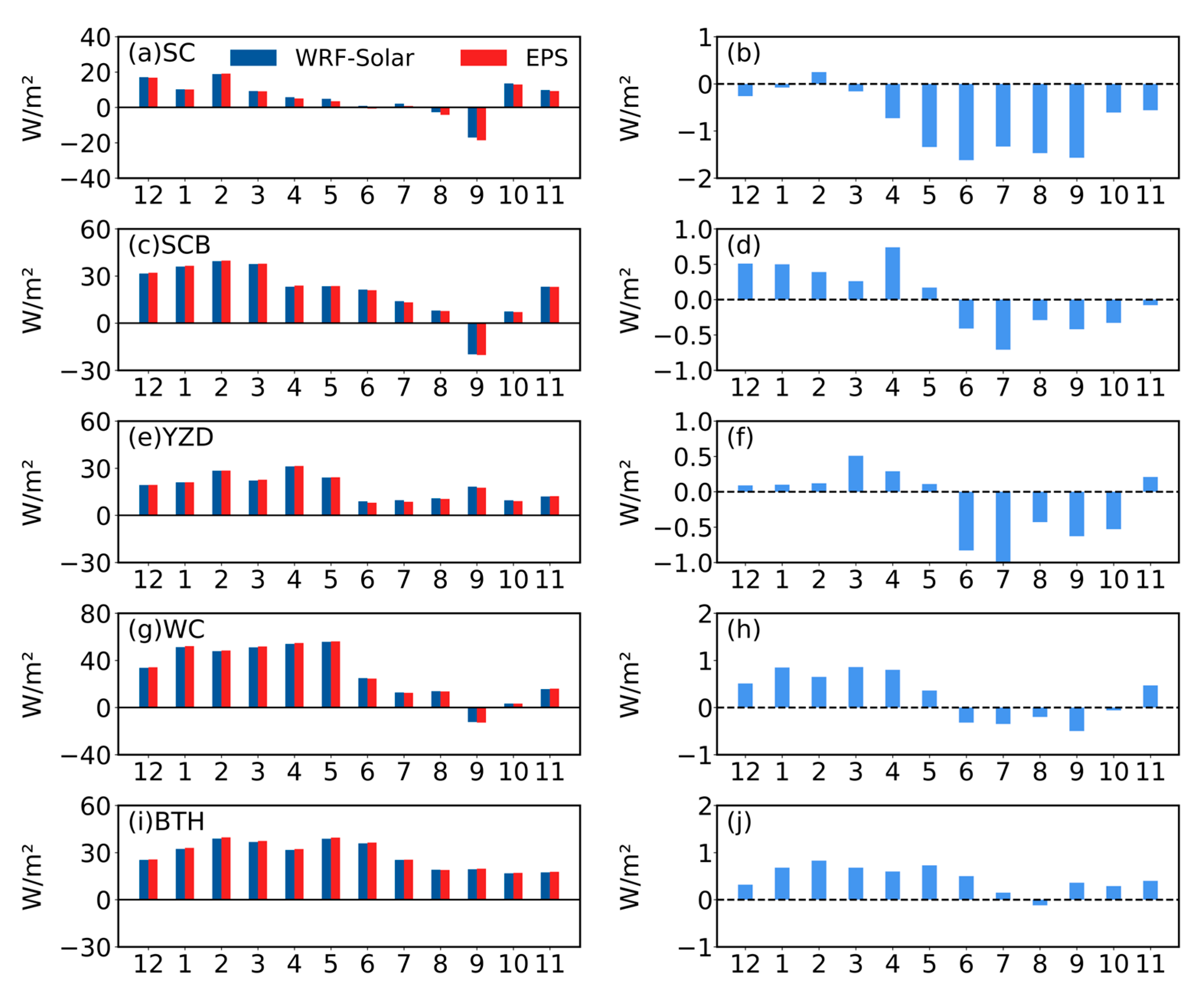

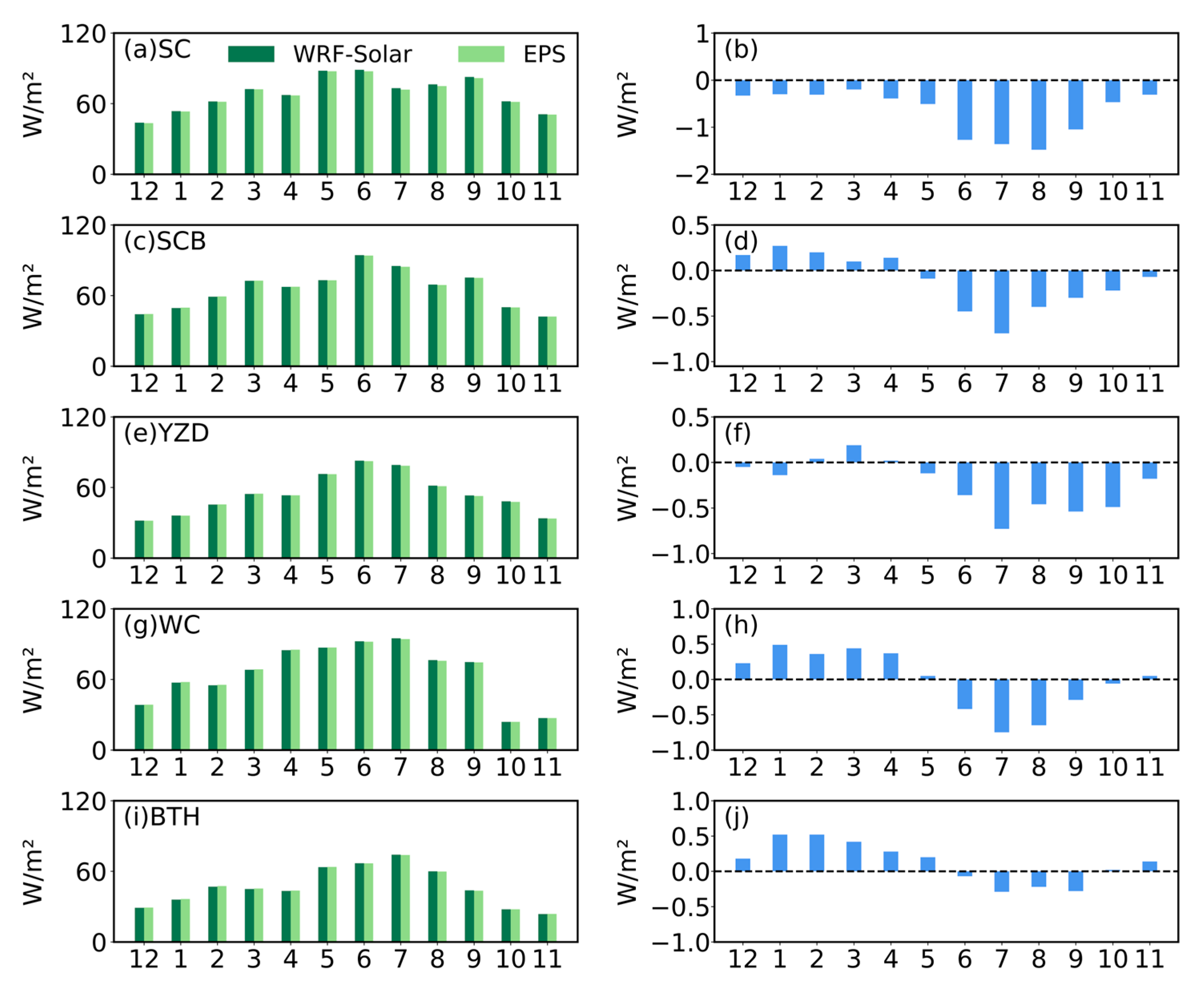

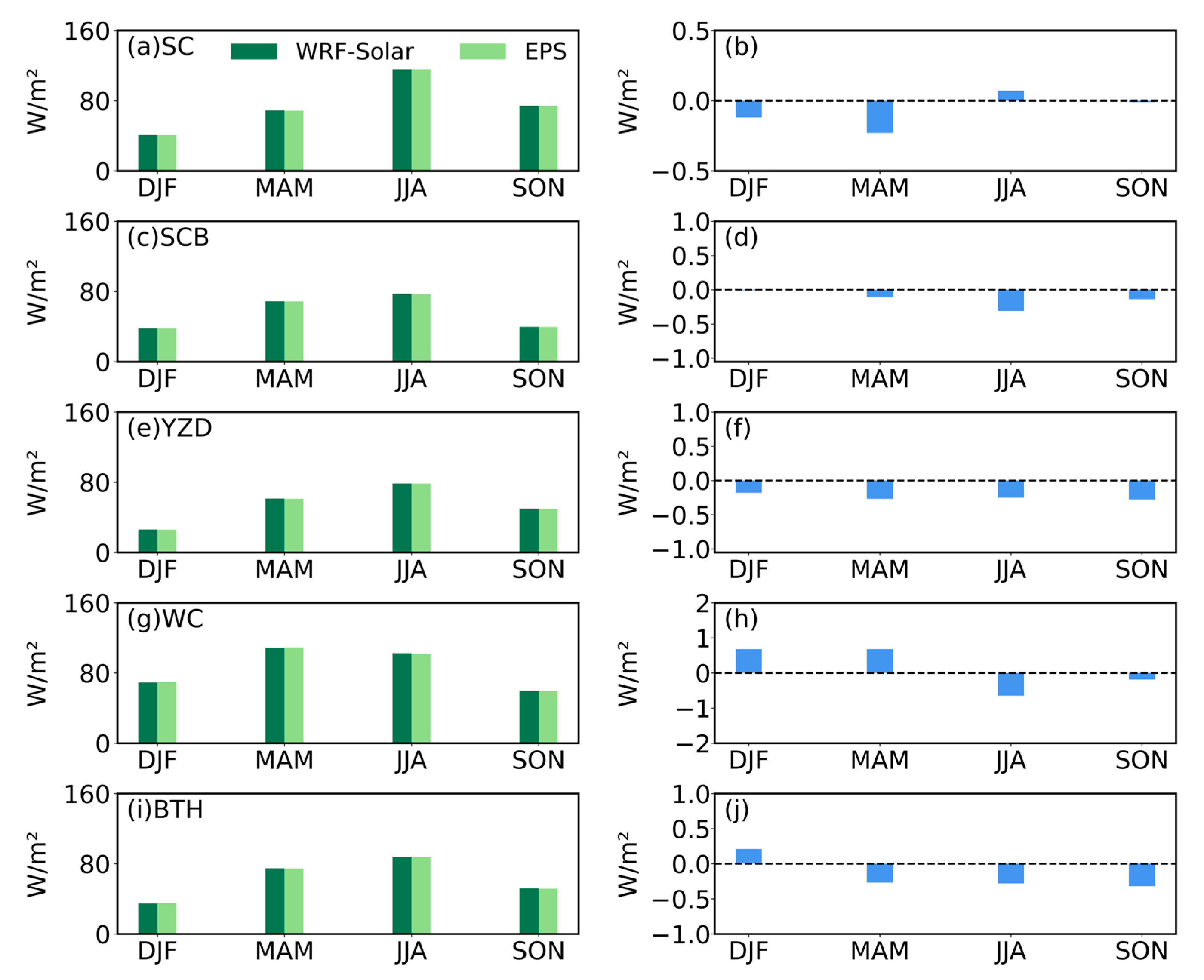

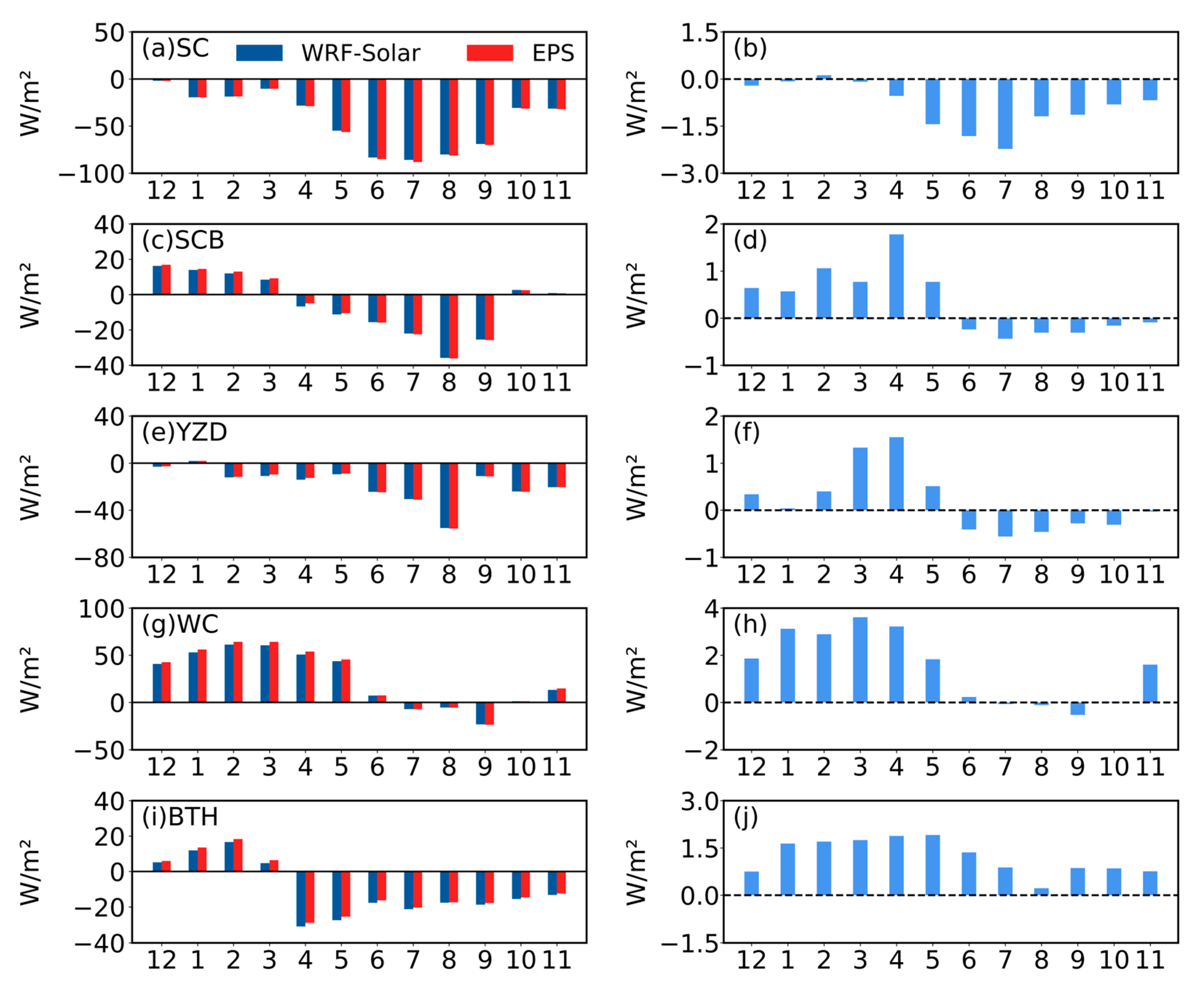

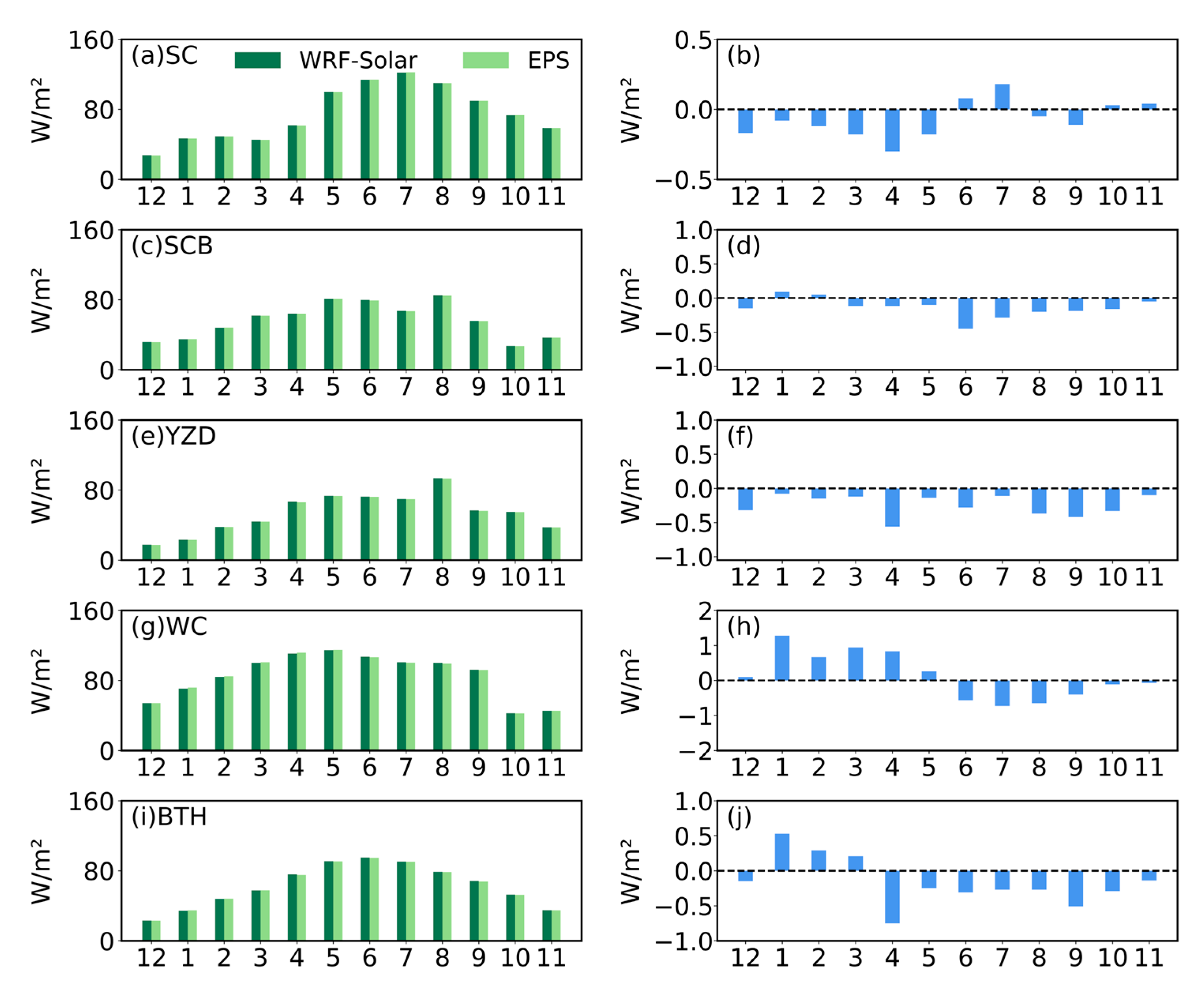

3.2. Assessment of WRF-Solar and EPS DIR Estimation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS effectively captured the spatial patterns of surface GHI over East Asia, with high radiation areas concentrated in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and Indo-China Peninsula, and low radiation areas in northern East Asia and the Sichuan Basin. However, both models exhibited a systematic overestimation of GHI compared to satellite retrievals over East Asia (annual mean biases: 17.27 W/m2for WRF-Solar and 17.68 W/m2for WRF-Solar EPS). Overestimations were most pronounced in northwest China, the North China Plain, the Sichuan Basin, and the northern Indian Peninsula. It is noted that the temporal patterns of bias and other error metrics (RMSE and MAE) diverged: maximum biases occurred in winter (DJF) and spring (MAM), whereas peak RMSE/MAE appeared in summer (JJA).

- (2)

- DIR exhibited larger regional disparities in model performance. Unlike GHI, DIR simulations showed contrasting biases: positive biases dominated the Tibetan Plateau, Qinghai, Gansu, and parts of the Gangetic Plain, while negative biases prevailed in southern China and the Indo-China Peninsula. Specifically, the WC was uniquely characterized by persistent overestimation, whereas the SC, SCB, YZD, and BTH exhibited significant underestimations. Both models yielded higher RMSE and MAE for DIR than for GHI, with peak errors in the SC and WC regions.

- (3)

- For short-term (≤36 h) predictions, WRF-Solar EPS performed comparably to WRF-Solar at the annual scale, with no statistically significant reduction in systematic biases for either GHI or DIR. However, modest improvements in RMSE and MAE were observed, particularly during JJA and SON, with the most notable enhancements in the SC region (e.g., RMSE reduced by up to 3.18 W/m2 in August for GHI). Conversely, limited benefits were seen in the BTH region, where minor increases in bias and error metrics were noted. These results indicate that while WRF-Solar EPS does not resolve the underlying systematic biases in short-term simulations, it marginally enhances predictive stability—an effect that varies by region and season.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NWP | Numerical weather prediction |

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting |

| WRF-Solar EPS | WRF-Solar Ensemble Prediction System |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

References

- Devabhaktuni, V.; Alam, M.; Depuru, S.S.S.R.; Green, R.C., II; Green, R.C.; Nims, D.; Near, C. Solar Energy: Trends and Enabling Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 19, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Adelodun, A.A.; Kim, K.-H. Solar Energy: Potential and Future Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yu, X.; Tian, C.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Zhong, J.; Guo, L.; Liu, L.; et al. Global Solar Droughts Due To Supply-Demand Imbalance Exacerbated by Anthropogenic Climate Change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.; Wei, L.; Zhangrong, P.; Chenchen, L.; Huiyuan, W.; Junhong, G. Spatiotemporal Changes in PV Potential and Extreme Characteristics in China under SSP Scenarios. Energy 2025, 320, 135215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, P.; Madsen, H.; Nielsen, H.A. Online Short-Term Solar Power Forecasting. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Kumar, K.R.; Inda, C.S. How Solar Radiation Forecasting Impacts the Utilization of Solar Energy: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 388, 135860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, R.H.; Pedro, H.T.C.; Coimbra, C.F.M. Solar Forecasting Methods for Renewable Energy Integration. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2013, 39, 535–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.S.; Yagli, G.M.; Kashyap, M.; Srinivasan, D. Solar Irradiance Resource and Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 1641–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; Min, M.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Jia, S. Accurate Nowcasting of Cloud Cover at Solar Photovoltaic Plants Using Geostationary Satellite Images. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Letu, H.; Nakajima, T.Y.; Nakajima, T.; Wei, L.; Xu, R.; Lu, F.; Riedi, J.; Ichii, K.; Zeng, J.; et al. Near-Global Monitoring of Surface Solar Radiation Through the Construction of a Geostationary Satellite Network Observation System. Innovation 2025, 6, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.W.; Urquhart, B.; Lave, M.; Dominguez, A.; Kleissl, J.; Shields, J.; Washom, B. Intra-Hour Forecasting with a Total Sky Imager at the UC San Diego Solar Energy Testbed. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 2881–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, M.; David, M.; Lauret, P.; Boland, J.; Schmutz, N. Review of Solar Irradiance Forecasting Methods and a Proposition for Small-Scale Insular Grids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Cesar, L.; Amaro e Silva, R.; Manso Callejo, M.Á.; Cira, C.-I. Review on Spatio-Temporal Solar Forecasting Methods Driven by In Situ Measurements or Their Combination with Satellite and Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) Estimates. Energies 2022, 15, 4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zuo, H.; Bai, Y.; Chang, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Ma, L.; Chen, B. A Multistep Short-Term Solar Radiation Forecasting Model Using Fully Convolutional Neural Networks and Chaotic Aquila Optimization Combining WRF-Solar Model Results. Energy 2023, 271, 126980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.A.; Hacker, J.P.; Dudhia, J.; Haupt, S.E.; Ruiz-Arias, J.A.; Gueymard, C.A.; Thompson, G.; Eidhammer, T.; Deng, A. WRF-Solar: Description and Clear-Sky Assessment of an Augmented NWP Model for Solar Power Prediction. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2016, 97, 1249–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, S.E.; Kosović, B.; Jensen, T.; Lazo, J.K.; Lee, J.A.; Jiménez, P.A.; Cowie, J.; Wiener, G.; McCandless, T.C.; Rogers, M.; et al. Building the Sun4Cast System: Improvements in Solar Power Forecasting. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 99, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.A.; Kay, M. Assessment of Simulated Solar Irradiance on Days of High Intermittency Using WRF-Solar. Energies 2020, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.A.; Yang, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Sengupta, M.; Dudhia, J. Assessing the WRF-Solar Model Performance Using Satellite-Derived Irradiance from the National Solar Radiation Database. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2022, 61, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sengupta, M.; Jiménez, P.A.; Kim, J.-H.; Xie, Y. Evaluating WRF-Solar EPS Cloud Mask Forecast Using the NSRDB. Sol. Energy 2022, 243, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, J.; Höller, R. Evaluation of High Resolution WRF Solar. Energies 2023, 16, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Jimenez, P.A.; Sengupta, M.; Yang, J.; Dudhia, J.; Alessandrini, S.; Xie, Y. The WRF-Solar Ensemble Prediction System to Provide Solar Irradiance Probabilistic Forecasts. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 48th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1233–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Jimenez, P.A.; Dudhia, J.; Yang, J.; Sengupta, M. A Gridded Solar Irradiance Ensemble Prediction System Based on WRF-Solar EPS and the Analog Ensemble. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Jiménez, P.A.; Sengupta, M.; Dudhia, J.; Xie, Y.; Golnas, A.; Giering, R. An Efficient Method to Identify Uncertainties of WRF-Solar Variables in Forecasting Solar Irradiance Using a Tangent Linear Sensitivity Analysis. Sol. Energy 2021, 220, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, A.; Heinemann, D.; Hoyer, C.; Kuhlemann, R.; Lorenz, E.; Müller, R.; Beyer, H.G. Solar Energy Assessment Using Remote Sensing Technologies. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amillo, A.G.; Huld, T.; Müller, R. A New Database of Global and Direct Solar Radiation Using the Eastern Meteosat Satellite, Models and Validation. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 8165–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M.; Xie, Y.; Lopez, A.; Habte, A.; Maclaurin, G.; Shelby, J. The National Solar Radiation Data Base (NSRDB). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letu, H.; Ma, R.; Nakajima, T.Y.; Shi, C.; Hashimoto, M.; Nagao, T.M.; Baran, A.J.; Nakajima, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, T.; et al. Surface Solar Radiation Compositions Observed from Himawari-8/9 and Fengyun-4 Series. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1772–E1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Ye, D.; Shen, Y.; Li, D.; Feng, J. Studies on the Improvement of Modelled Solar Radiation and the Attenuation Effect of Aerosol Using the WRF-Solar Model with Satellite-Based AOD Data over North China. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-B.; Wang, L.-C.; Zhou, J.-J.; Niu, Z.-G.; Zhang, M.; Qin, W.-M. Assessment of the High-Resolution Estimations of Global and Diffuse Solar Radiation Using WRF-Solar. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2023, 14, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Tang, X.; Hu, B.; Chen, K.; Wu, Q.; Kong, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J. Evaluation of the Simulation Performance of WRF-Solar for a Summer Month in China Using Ground Observation Network Data. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2025, 18, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, S. Impact of Aerosols on NPP in Basins: Case Study of WRF−Solar in the Jinghe River Basin. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shi, H.; Fu, D.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Shan, Y.; Hong, T.; Yang, D.; Xia, X. Moving beyond the Aerosol Climatology of WRF-Solar: A Case Study over the North China Plain. Weather Forecast. 2024, 39, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Hua, T.; Liu, L.; Ma, X.; Tharaka, W.A.N.D.; Xing, Y.; Deng, Z.; Shen, L. Assessing Aerosol-Radiation Interaction with WRF-Chem-Solar: Case Study on the Impact of the “Pollution Reduction and Carbon Reduction Synergy” Policy. Atmos. Res. 2024, 308, 107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Chen, L.; Letu, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Bao, S. Development of a Daytime Cloud and Haze Detection Algorithm for Himawari-8 Satellite Measurements over Central and Eastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 3528–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M.; Jimenez, P.; Kim, J.-H.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Final Report on Probabilistic Cloud Optimized Day-Ahead Forecasting System Based on WRF-Solar; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.J.; Delamere, J.S.; Mlawer, E.J.; Shephard, M.W.; Clough, S.A.; Collins, W.D. Radiative Forcing by Long-Lived Greenhouse Gases: Calculations with the AER Radiative Transfer Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D13103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Field, P.R.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Hall, W.D. Explicit Forecasts of Winter Precipitation Using an Improved Bulk Microphysics Scheme. Part II: Implementation of a New Snow Parameterization. Mon. Weather Rev. 2008, 136, 5095–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Niino, H. Development of an Improved Turbulence Closure Model for the Atmospheric Boundary Layer. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2009, 87, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Dudhia, J. Coupling an Advanced Land Surface–Hydrology Model with the Penn State–NCAR MM5 Modeling System. Part I: Model Implementation and Sensitivity. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2001, 129, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Dévényi, D. A Generalized Approach to Parameterizing Convection Combining Ensemble and Data Assimilation Techniques. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegen, I.; Hollrig, P.; Chin, M.; Fung, I.; Jacob, D.; Penner, J. Contribution of Different Aerosol Species to the Global Aerosol Extinction Optical Thickness: Estimates from Model Results. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1997, 102, 23895–23915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Feng, S.; Berg, L.K.; Juliano, T.W.; Jiménez, P.A.; Liu, Y. Sensitivity of Solar Irradiance to Model Parameters in Cloud and Aerosol Treatments of WRF-Solar. Sol. Energy 2022, 233, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, G.; Sogacheva, L.; Rodriguez, E.; Kourtidis, K.; Georgoulias, A.K.; Alexandri, G.; Amiridis, V.; Proestakis, E.; Marinou, E.; Xue, Y.; et al. Two Decades of Satellite Observations of AOD over Mainland China Using ATSR-2, AATSR and MODIS/Terra: Data Set Evaluation and Large-Scale Patterns. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 1573–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Xu, H.; Li, K.T.; Li, D.H.; Xie, Y.S.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.F.; Zhao, W.; Tian, Q.J.; et al. Comprehensive Study of Optical, Physical, Chemical, and Radiative Properties of Total Columnar Atmospheric Aerosols over China: An Overview of Sun–Sky Radiometer Observation Network (SONET) Measurements. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 99, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.C.B.; de Almeida Dantas, V.; dos Reis, J.S.; de Assis Bose, N.; de Azevedo Santos Emiliavaca, S.; Cruz Bezerra, L.A.; de Fátima Alves de Matos, M.; de Mello Nobre, M.T.C.; de Lima Oliveira, L.; de Medeiros, A.M. Analysis of WRF-Solar in the Estimation of Global Horizontal Irradiation in Amapá, Northern Brazil. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamees, A.S.; Sayad, T.; Morsy, M.; Ali Rahoma, U. Evaluation of Three Radiation Schemes of the WRF-Solar Model for Global Surface Solar Radiation Forecast: A Case Study in Egypt. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 2880–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadogo, W.; Fersch, B.; Bliefernicht, J.; Meilinger, S.; Rummler, T.; Salack, S.; Guug, S.; Kunstmann, H. Evaluation of the WRF-Solar Model for 72-Hour Ahead Forecasts of Global Horizontal Irradiance in West Africa: A Case Study for Ghana. Sol. Energy 2024, 271, 112413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhao, C.; Cribb, M.C.; Dong, X.; Fan, J.; Gong, D.; Huang, J.; Jiang, M.; et al. East Asian Study of Tropospheric Aerosols and Their Impact on Regional Clouds, Precipitation, and Climate (EAST-AIRCPC). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 13026–13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Shan, Y.; Endo, S.; Xie, Y.; Sengupta, M. Influences of Cloud Microphysics on the Components of Solar Irradiance in the WRF-Solar Model. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Feng, S.; Berg, L.K.; Juliano, T.W.; Jiménez, P.A.; Grimit, E.; Liu, Y. Calibration of Cloud and Aerosol Related Parameters for Solar Irradiance Forecasts in WRF-Solar. Sol. Energy 2022, 241, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lu, B.; Chen, M.; Guo, C. Revealing Key Factor in Cloud Radiation Processes Affecting Global Horizontal Irradiance in WRF-Solar in China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Eidhammer, T. A Study of Aerosol Impacts on Clouds and Precipitation Development in a Large Winter Cyclone. J. Atmos. Sci. 2014, 71, 3636–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Nagao, T.M.; Murakami, H.; Nomaki, T.; Higurashi, A. Common Retrieval of Aerosol Properties for Imaging Satellite Sensors. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2018, 96B, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Murakami, H.; Suzuki, K.; Nagao, T.M.; Higurashi, A. Improved Hourly Estimates of Aerosol Optical Thickness Using Spatiotemporal Variability Derived from Himawari-8 Geostationary Satellite. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 3442–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Shi, H.; Gueymard, C.A.; Yang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Che, H.; Fan, X.; Han, X.; Gao, L.; Bian, J.; et al. A Deep-Learning and Transfer-Learning Hybrid Aerosol Retrieval Algorithm for FY4-AGRI: Development and Verification over Asia. Engineering 2024, 38, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Setting | WRF-Solar | WRF-Solar EPS |

|---|---|---|

| microphysical scheme | Thompson | Thompson |

| longwave and shortwaveradiation scheme | RRTMG | RRTMG |

| planetary boundary layer scheme | MYNN | MYNN |

| land surface scheme | Noah | Noah |

| cumulus cloud scheme | Grell-3D | Grell-3D |

| sub-grid-scale cloud scheme | CLD3 | CLD3 |

| AOD data | monthly climatology | monthly climatology |

| stochastic perturbations | off | on |

| Regions of Interest | Abbreviation | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| South China | SC | 17.5°N–26°N | 108°E–118°E |

| Sichuan Basin | SCB | 27°S–34°N | 102°E–109°E |

| Yangtze River Delta | YZD | 27°N–34°N | 116°E–123.5°E |

| Western China | WC | 26°N–40°N | 82°E–98°E |

| Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei | BTH | 35.5°N–43°N | 113°E–120°E |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Gui, K.; Ma, J.; Che, H. Assessment of WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS Radiation Estimation in Asia Using the Geostationary Satellite Measurement. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3970. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243970

Zhang H, Li L, Zhang X, Liu S, Zheng Y, Gui K, Ma J, Che H. Assessment of WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS Radiation Estimation in Asia Using the Geostationary Satellite Measurement. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3970. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243970

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Haoling, Lei Li, Xindan Zhang, Shuhui Liu, Yu Zheng, Ke Gui, Jingrui Ma, and Huizheng Che. 2025. "Assessment of WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS Radiation Estimation in Asia Using the Geostationary Satellite Measurement" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3970. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243970

APA StyleZhang, H., Li, L., Zhang, X., Liu, S., Zheng, Y., Gui, K., Ma, J., & Che, H. (2025). Assessment of WRF-Solar and WRF-Solar EPS Radiation Estimation in Asia Using the Geostationary Satellite Measurement. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3970. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243970