Advancing Wildfire Damage Assessment with Aerial Thermal Remote Sensing and AI: Applications to the 2025 Eaton and Palisades Fires

Highlights

- By leveraging multiple data sources, innovative data processing techniques, and machine learning, an approach is presented for leveraging aerial thermal imagery to automate assessment of structural damage caused by active wildfires.

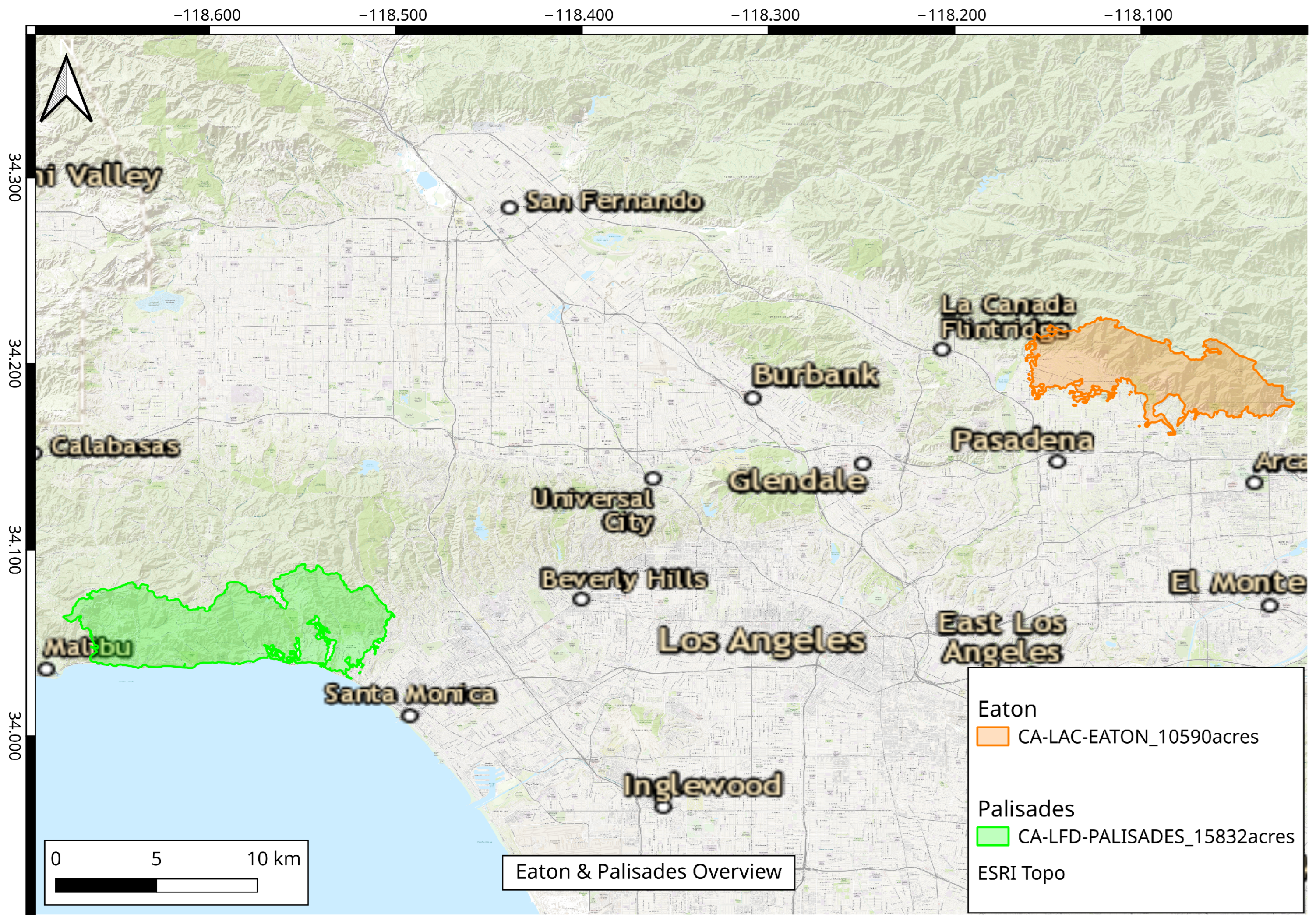

- The effectiveness of the approach is demonstrated by applying it to the 2025 Eaton and Palisades wildfires in California.

- The proposed approach offers rapid and reliable assessment of damaged structures from wildfires using imagery that was once not widely available. With more rapid data collection in California, these refined techniques can provide more rapid and accurate assessments.

- The proposed approach is suitable for operational wildfire damage assessment and provides insights to variation in fire behavior, as seen in heat intensities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Related Work

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Imagery Processing

2.3. Data Preparation

2.3.1. Feature Extraction

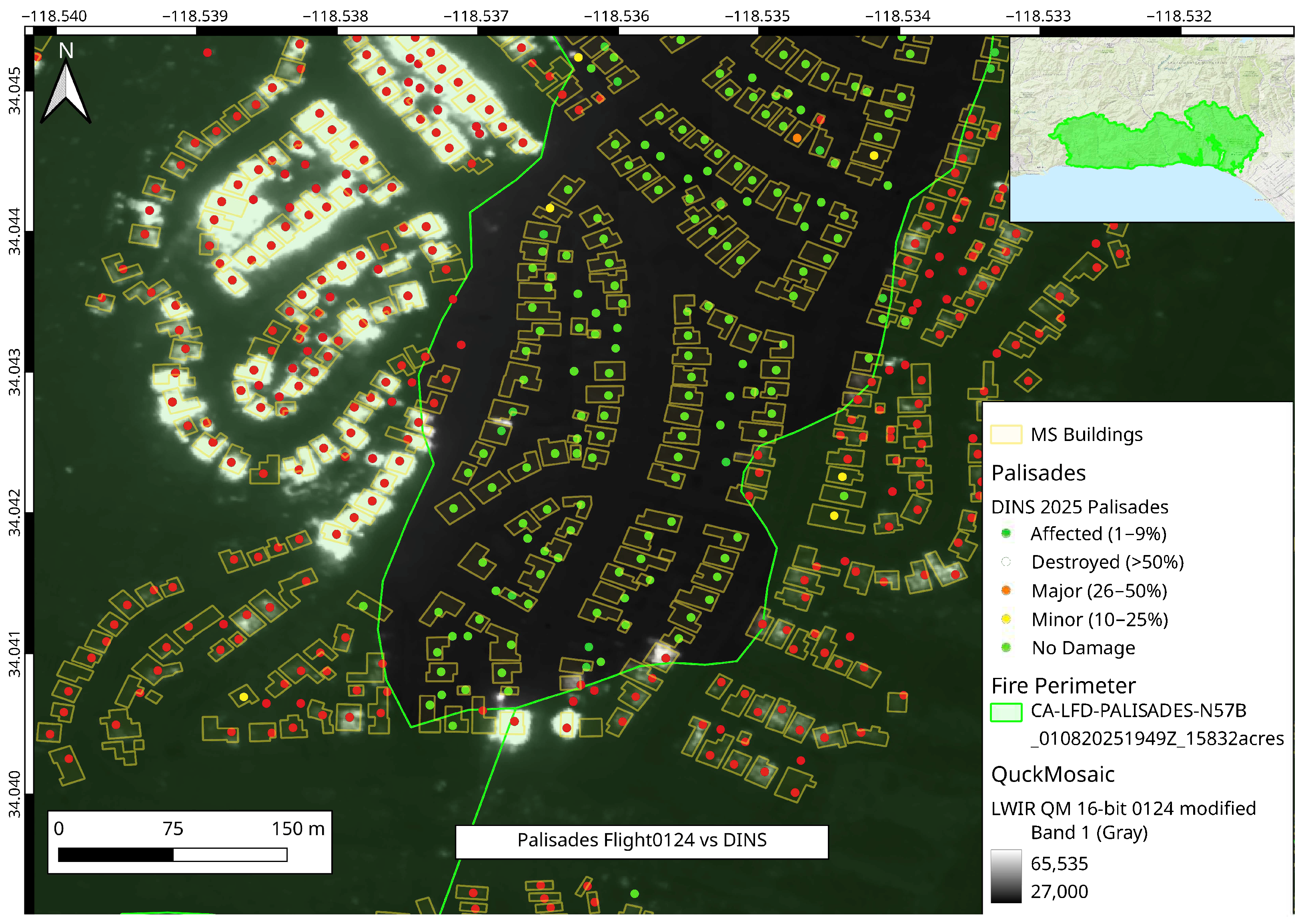

2.3.2. Fire Perimeter Restriction

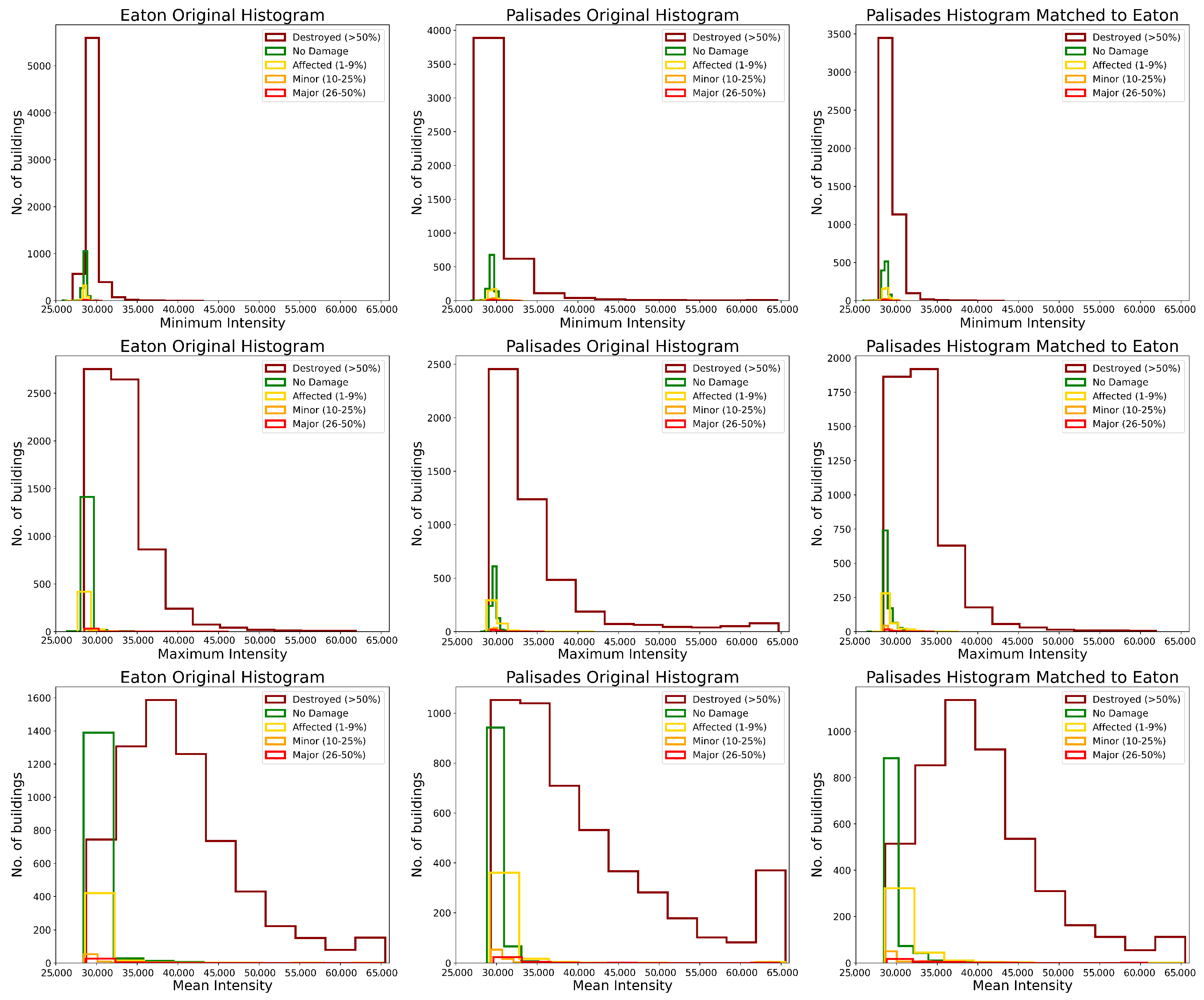

2.3.3. Domain Adaptation Using Histogram Matching

2.4. Machine Learning Setup

- Destroyed —More than 50% damage;

- Major—Between 26 and 50% damage;

- Minor—Between 10 and 25% damage;

- Affected—Less than 10% damage;

- No Damage;

- Inaccessible.

3. Experimental Setup and Results

3.1. Experimental Setup

- Resolution: Full Resolution vs. Quick MosaicThe first set of experiments compares model performance between full-resolution (FR) and Quick Mosaic (QM) IR data. Full-resolution mosaics are refined post-flight products that undergo extensive human-assisted rectification and alignment, providing high spatial precision but requiring considerable processing time before they can be used. Quick Mosaics, on the other hand, are automatically stitched and rapidly released following data collection, enabling near-real-time readiness with minimal preprocessing. This experiment evaluates the effectiveness of these two data products in supporting ML-based damage classification, with a focus on understanding how differences in data preparation and spatial detail influence overall model performance.

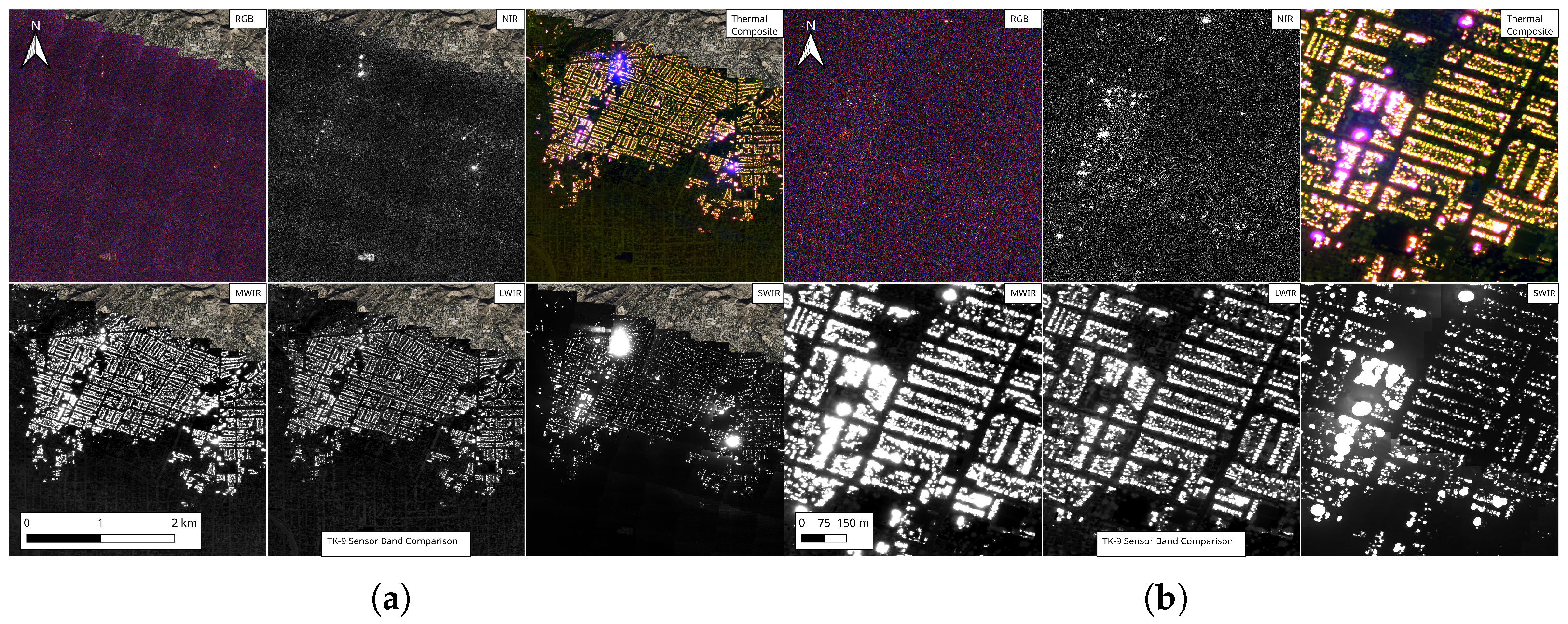

- IR Bands: LWIR vs. MWIR vs. SWIR vs. Thermal Composite (TC)The second set of experiments evaluates model performance across different infrared spectral bands, namely long-wave infrared (LWIR), mid-wave infrared (MWIR), short-wave infrared (SWIR), and thermal composite (TC) imagery. Each single-band mosaic captures a distinct portion of the thermal spectrum, providing complementary information on fire intensity and post-fire heat distribution. The thermal composite (TC) Quick Mosaics integrate three bands—LWIR, MWIR, and SWIR—into a single three-channel composite product. Since each spectral band is originally provided separately, using TC mosaics could potentially eliminate the need for individual preprocessing pipelines and per-band model evaluations. These experiments therefore investigate whether TC imagery can serve as a standard unified data product capable of preserving the discriminative power of separate bands. This comparison is crucial, as the relative performance of MWIR and LWIR in particular may vary based on environmental conditions such as time of day, fire intensity, topography, and atmospheric effects.

- Data Type: 16-bit vs. 8-bitThese experiments are designed to evaluate the impact of radiometric resolution on classification performance. The initial default is the 8-bit Quick Mosaic, which is efficient for storage, faster to process, and easier for humans to inspect when analyzing thermal signatures in damaged buildings. The 16-bit Quick Mosaics preserve the full range of sensor intensity values, capturing subtle variations in thermal response that may be important for accurately distinguishing damage levels [28]. In contrast, the 8-bit products, while easier to store and interpret, may lose some of these fine details that a machine learning model could use. This experiment evaluates whether the extra computational and storage cost of 16-bit mosaics is justified by improvements in model performance.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Full Resolution vs. Quick Mosaic

3.2.2. IR Band Comparison

3.2.3. 16-Bit vs. 8-Bit

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance of Our Results

- Differences in topography, which influences wind speed and direction, since Palisades is predominantly hilly and separated by canyons versus the mostly contiguous, flat, and gently sloped Eaton area downwind of the San Gabriel Mountains; for the effect of topography on the image preprocessing, we found that the areas of high topographic relief affected the amount of distortion in the generated full-resolution and QuickMosaic mosaics.

- Differences in predominant fuels based on vegetation types at the Wildland–Urban Interface (WUI), since Palisades is at the coast and likely experiences more regular moisture and subsequent vegetation growth, while Eaton is approximately 25 miles (40 km) further inland and presumably much drier (Figure 3).

- Differences in the fire environment impacting the probability of ignition (PIG) and neighborhood burn times, potentially due to building density, landscaping, construction type (residential, commercial, etc.) and material (wood-frame, concrete, etc.), age (building codes), and form (density and setbacks).

- And/or differences in the time of day the imagery was collected and its global effect on intensity values, particularly where the low-intensity damage thresholds separating burning structures and objects at elevated fire-warmed and ambient temperatures increasingly overlap.

4.2. Data Challenges

4.2.1. Building Footprint Data

4.2.2. Damage Inspection (DINS) Data Limitations

4.2.3. Imagery

4.3. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. FIRIS. 2025. Available online: https://www.caloes.ca.gov/office-of-the-director/operations/response-operations/fire-rescue/firis/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- CAL FIRE. Top 20 Most Destructive California Wildfires. 2025. Available online: https://34c031f8-c9fd-4018-8c5a-4159cdff6b0d-cdn-endpoint.azureedge.net/-/media/calfire-website/our-impact/fire-statistics/top-20-destructive-ca-wildfires.pdf?rev=737a1073f76947b4a3bfb960b19f44c7&hash=7CA02D30D9BF46A32D5D98BD108BA26A (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Galanis, M.; Rao, K.; Yao, X.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Ventura, J.; Fricker, G.A. DamageMap: A post-wildfire damaged buildings classifier. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 65, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Goodman, B.; Patel, N.; Hosfelt, R.; Sajeev, S.; Heim, E.; Doshi, J.; Lucas, K.; Choset, H.; Gaston, M. Creating xBD: A Dataset for Assessing Building Damage from Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, H.; Baireddy, S.; Bartusiak, E.R.; Konz, L.; LaTourette, K.; Gribbons, M.; Chan, M.; Comer, M.L.; Delp, E.J. An Attention-Based System for Damage Assessment Using Satellite Imagery. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.06643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farasin, A.; Colomba, L.; Garza, P. Double-step U-Net: A deep learning-based approach for the estimation of wildfire damage severity through Sentinel-2 satellite data. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shafian, S.; Hu, D. Integrating Machine Learning and Remote Sensing in Disaster Management: A Decadal Review of Post-Disaster Building Damage Assessment. Buildings 2024, 14, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Lian, I.B. Building a Vision Transformer-Based Damage Severity Classifier with Ground-Level Imagery of Homes Affected by California Wildfires. Fire 2024, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.; Perez, J. GIS and Deep Learning Make Damage Assessments More Timely and Precise. 2024. Available online: https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcuser/lahaina (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Du, Y.N.; Feng, D.C. A rapid and quantitative post-wildfire damage assessment of buildings in the 2025 Palisades fire in California based on InSAR. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 129, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, S.; Nguyen, M.H.; Crawl, D.; Block, J.; Al Rawaf, R.; Hart, F.; Campbell, M.; Scott, R.; Altintas, I. Near Real-Time Wildfire Damage Assessment using Aerial Thermal Imagery and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TK Sensors | Overwatch Imaging | Delivering Critical Intelligence Through Faster Automation. Available online: https://www.overwatchimaging.com/tk-sensor-payloads (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Microsoft Planetary Computer. Microsoft Planetary Computer. Available online: https://planetarycomputer.microsoft.com/dataset/ms-buildings (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. CAL FIRE. 2025. Available online: https://www.fire.ca.gov/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- CAL FIRE Damage Inspection (DINS) Data. Available online: https://gis.data.cnra.ca.gov/datasets/CALFIRE-Forestry::cal-fire-damage-inspection-dins-data/about (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- QGIS Changelog: Versions. Available online: https://changelog.qgis.org/en/version/list/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- QGIS Documentation Georeferencer. Available online: https://docs.qgis.org/3.40/en/docs/user_manual/managing_data_source/georeferencer.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Dubinin, M. QuickMapServices: Easy Basemaps in QGIS. Available online: https://nextgis.com/blog/quickmapservices/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- QGIS Documentation Raster Miscellaneous. Available online: https://docs.qgis.org/3.40/en/docs/user_manual/processing_algs/gdal/rastermiscellaneous.html#merge (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Agisoft Metashape. Available online: https://www.agisoft.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Gonzalez, R.C. Digital Image Processing; Pearson Education India: Noida, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J.P.; Vo, V.; Bloss, B.; Abbey, C.K. Fast algorithms for histogram matching: Application to texture synthesis. J. Electron. Imaging 2000, 9, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, P. Histogram Matching—Paulbourke.net. 2011. Available online: https://paulbourke.net/miscellaneous/equalisation/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Bottenus, N.; Byram, B.C.; Hyun, D. Histogram Matching for Visual Ultrasound Image Comparison. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Shi, L.; Luo, Y.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Liang, P.; Li, K.; Mok, V.C.T.; Chu, W.C.W.; Wang, D. Histogram-based normalization technique on human brain magnetic resonance images from different acquisitions. BioMed. Eng. OnLine 2015, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baktashmotlagh, M.; Harandi, M.; Salzmann, M. Distribution-matching embedding for visual domain adaptation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 17, 3760–3789. [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt, S.; Schönberger, J.L.; Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Boulogne, F.; Warner, J.D.; Yager, N.; Gouillart, E.; Yu, T. scikit-image: Image processing in Python. PeerJ 2014, 2, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verde, N.; Mallinis, G.; Tsakiri-Strati, M.; Georgiadis, C.; Patias, P. Assessment of Radiometric Resolution Impact on Remote Sensing Data Classification Accuracy. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, F.S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: Overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2022, 75, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USA Structures. Available online: https://gis-fema.hub.arcgis.com/pages/usa-structures (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- OSM Buildings. Available online: https://osmbuildings.org/copyright/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sebastian, B.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Balakrishnan, K. Gray Level Co-Occurrence Matrices: Generalisation and Some New Features. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1205.4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Law, M.W.K.; Chung, A.C.S. Dominant Local Binary Patterns for Texture Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2009, 18, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.07193. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.T.; Hu, R.; Ryali, C.; Ma, T.; Khedr, H.; Rädle, R.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; et al. SAM 2: Segment Anything in Images and Videos. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- GRASS GIS Manual r.series. Available online: https://grass.osgeo.org/grass-stable/manuals/r.series.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Image Type | Data Type | File Format | Geocorrection Level | CRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quick Mosaic | 8-bit | GeoTIFF | Fastest | EPSG 4326 |

| Quick Mosaic | 16-bit | GeoTIFF | Best | EPSG 4326 |

| FullRes | 16-bit | GeoTIFF | Manual | EPSG 4326 |

| Image Type | Transform Method | Resampling Method | Compression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quick Mosaic 8-bit | Thin Plate Spline | Cubic B-Spline (4 × 4 Kernel) | Deflate |

| Quick Mosaic 16-bit | Thin Plate Spline | Cubic B-Spline (4 × 4 Kernel) | Deflate |

| Full-Res 16-bit | Thin Plate Spline | Cubic B-Spline (4 × 4 Kernel) | N/A |

| Fire | No Damage | Affected | Minor | Major | Destroyed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palisades | 1029 | 393 | 80 | 33 | 4217 |

| Eaton | 1446 | 452 | 73 | 35 | 6671 |

| Multi-Class | Binary | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fire | Res | ACC | F1 | AUC | ACC | F1 | AUC |

| Palisades | QM | 0.8633 (0.0064) | 0.8516 (0.0007) | 0.9544 (0.0014) | 0.9178 (0.0030) | 0.9184 (0.0034) | 0.9573 (0.0026) |

| FR | 0.8461 (0.0009) | 0.8267 (0.0015) | 0.9351 (0.0007) | 0.8867 (0.0013) | 0.8893 (0.0011) | 0.9448 (0.0014) | |

| Multi-Class | Binary | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Band | ACC | F1 | AUC | ACC | F1 | AUC |

| Palisades | Eaton | SWIR | 0.6887 (0.0028) | 0.6534 (0.0021) | 0.6065 (0.0079) | 0.6609 (0.0019) | 0.6731 (0.0021) | 0.6294 (0.0039) |

| MWIR | 0.8548 (0.0015) | 0.8548 (0.0011) | 0.9557 (0.0003) | 0.9168 (0.0010) | 0.9181 (0.0010) | 0.9648 (0.0017) | ||

| LWIR | 0.8867 (0.0011) | 0.8694 (0.0009) | 0.9609 (0.0010) | 0.9394 (0.0010) | 0.9394 (0.0009) | 0.9734 (0.0003) | ||

| TC | 0.8729 (0.0047) | 0.8613 (0.0032) | 0.9608 (0.0029) | 0.9206 (0.0013) | 0.9204 (0.0015) | 0.9675 (0.0006) | ||

| Eaton | Palisades | SWIR | 0.6451 (0.0009) | 0.6424 (0.0007) | 0.6054 (0.0031) | 0.6879 (0.0019) | 0.6911 (0.0014) | 0.6018 (0.0028) |

| MWIR | 0.8004 (0.0071) | 0.7832 (0.0039) | 0.9051 (0.0024) | 0.8807 (0.0010) | 0.8810 (0.0010) | 0.9312 (0.0047) | ||

| LWIR | 0.8393 (0.0023) | 0.8300 (0.0016) | 0.9278 (0.0033) | 0.9048 (0.0012) | 0.9051 (0.0010) | 0.9405 (0.0022) | ||

| TC | 0.8380 (0.0019) | 0.8321 (0.0017) | 0.9280 (0.0040) | 0.9050 (0.0011) | 0.9053 (0.0009) | 0.9259 (0.0064) | ||

| Multi-Class | Binary | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Data Type | ACC | F1 | AUC | ACC | F1 | AUC | Time (in s) |

| Palisades | Eaton | 16-bit | 0.8867 (0.0011) | 0.8694 (0.0009) | 0.9609 (0.0010) | 0.9394 (0.0010) | 0.9394 (0.0009) | 0.9734 (0.0003) | 38.39 (0.78) |

| 8-bit | 0.8794 (0.0015) | 0.8710 (0.0011) | 0.9629 (0.0009) | 0.9348 (0.0008) | 0.9362 (0.0008) | 0.9773 (0.0002) | 29.76 (1.20) | ||

| Eaton | Palisades | 16-bit | 0.8393 (0.0023) | 0.8300 (0.0016) | 0.9278 (0.0033) | 0.9048 (0.0012) | 0.9051 (0.0010) | 0.9405 (0.0022) | 48.41 (0.70) |

| 8-bit | 0.8035 (0.0045) | 0.7962 (0.0021) | 0.8721 (0.0008) | 0.8625 (0.0021) | 0.8632 (0.0016) | 0.8788 (0.0022) | 31.56 (0.94) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trivedi, S.; al Rawaf, R.; Hart, F.; Block, J.; Nguyen, M.H.; Roten, D.; Crawl, D.; Scott, R.; Martin, M.; Pahalek, C.; et al. Advancing Wildfire Damage Assessment with Aerial Thermal Remote Sensing and AI: Applications to the 2025 Eaton and Palisades Fires. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243962

Trivedi S, al Rawaf R, Hart F, Block J, Nguyen MH, Roten D, Crawl D, Scott R, Martin M, Pahalek C, et al. Advancing Wildfire Damage Assessment with Aerial Thermal Remote Sensing and AI: Applications to the 2025 Eaton and Palisades Fires. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243962

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrivedi, Siddharth, Rawaf al Rawaf, Francesca Hart, Jessica Block, Mai H. Nguyen, Daniel Roten, Daniel Crawl, Robert Scott, Michael Martin, Chris Pahalek, and et al. 2025. "Advancing Wildfire Damage Assessment with Aerial Thermal Remote Sensing and AI: Applications to the 2025 Eaton and Palisades Fires" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243962

APA StyleTrivedi, S., al Rawaf, R., Hart, F., Block, J., Nguyen, M. H., Roten, D., Crawl, D., Scott, R., Martin, M., Pahalek, C., Rodriguez, E., & Altintas, I. (2025). Advancing Wildfire Damage Assessment with Aerial Thermal Remote Sensing and AI: Applications to the 2025 Eaton and Palisades Fires. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243962