Effects of Prescribed Fire on Spatial Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Spectral Diversity Using Hyperspectral Imagery from Savannah Landscapes on the Edwards Plateau of Texas, USA

Highlights

- What are the main findings?

- Weather and soil moisture shaped spectral diversity, whereas fire dampened the effects of reduced precipitation for spectral indices indicative of plant functional traits like canopy structure, greenness, and chlorophyll content. Although functional trait spectral indices declined with dry-down, the declines were smaller in burned areas.

- Fire substantially influenced the spatial patterns of spectral evenness and functional trait indices. Fire disrupted the spatial patterns of spectral evenness (but not β-diversity) and spectral functional traits. Additionally, the combined effects of fire and dry-down increased spatial heterogeneity in spectral evenness and in spectral indices indicative of biophysical and biochemical traits across scales.

- What is the implication of the main finding?

- Prescribed fire can modestly moderate drought impacts but does not override soil–climate controls. Fire’s influence on vegetation resilience operates mainly through short-term phenological effects rather than large shifts in spectral diversity and savanna ecosystems’ functional diversity and resilience under changing rainfall patterns, highlighting the need to integrate climate forecasts into fire management plans.

- Hyperspectral remote sensing supports adaptive fire management. Multi-scale hyperspectral monitoring can inform adaptive fire management by identifying where functional recovery is strongest and where environmental constraints limit post-fire vegetation responses.

Abstract

1. Introduction

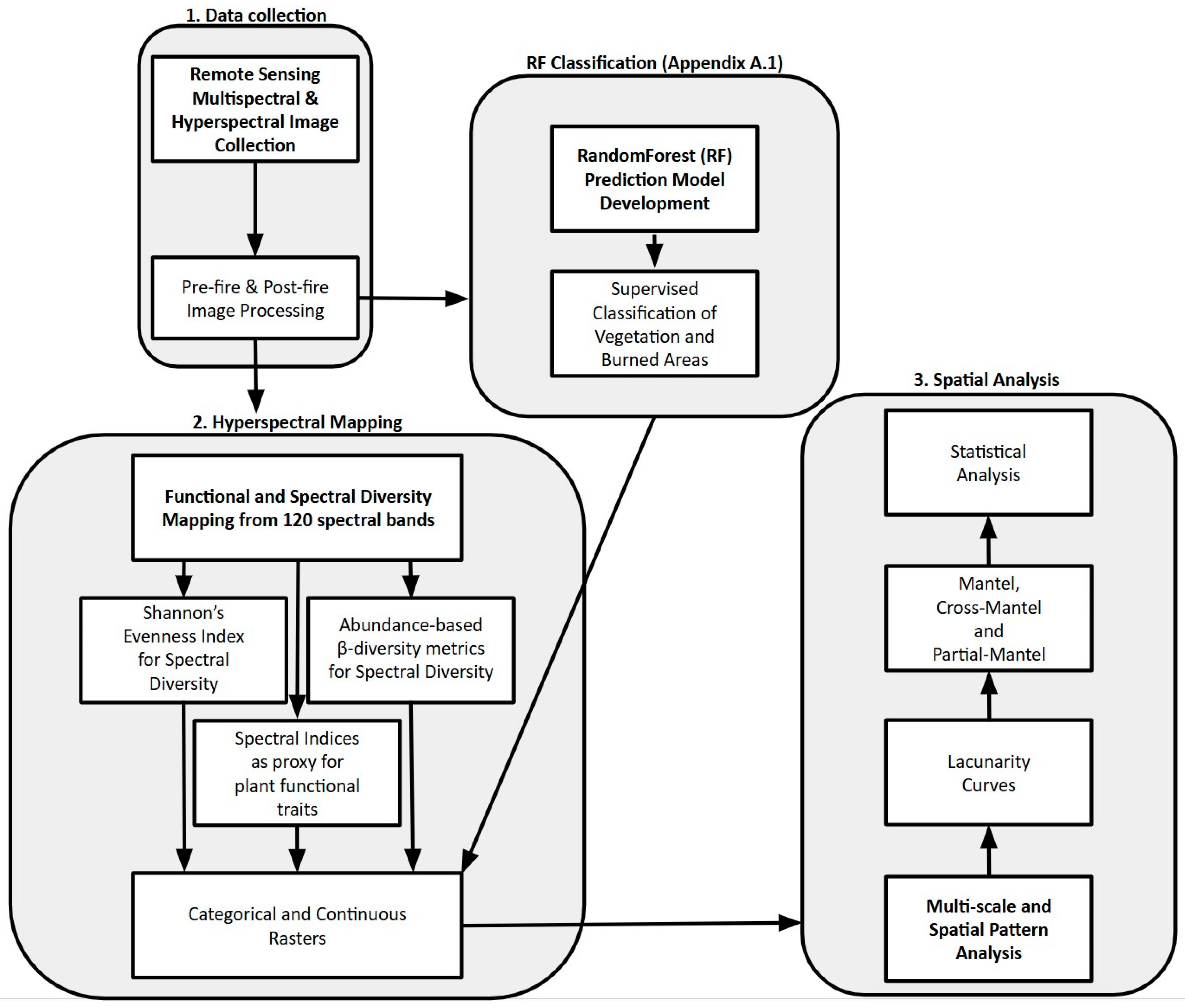

2. Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Remote Sensing Data

2.3. Indices of Plant Functional Traits

2.4. Spectral Evenness and β-Diversity

2.5. Lacunarity Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

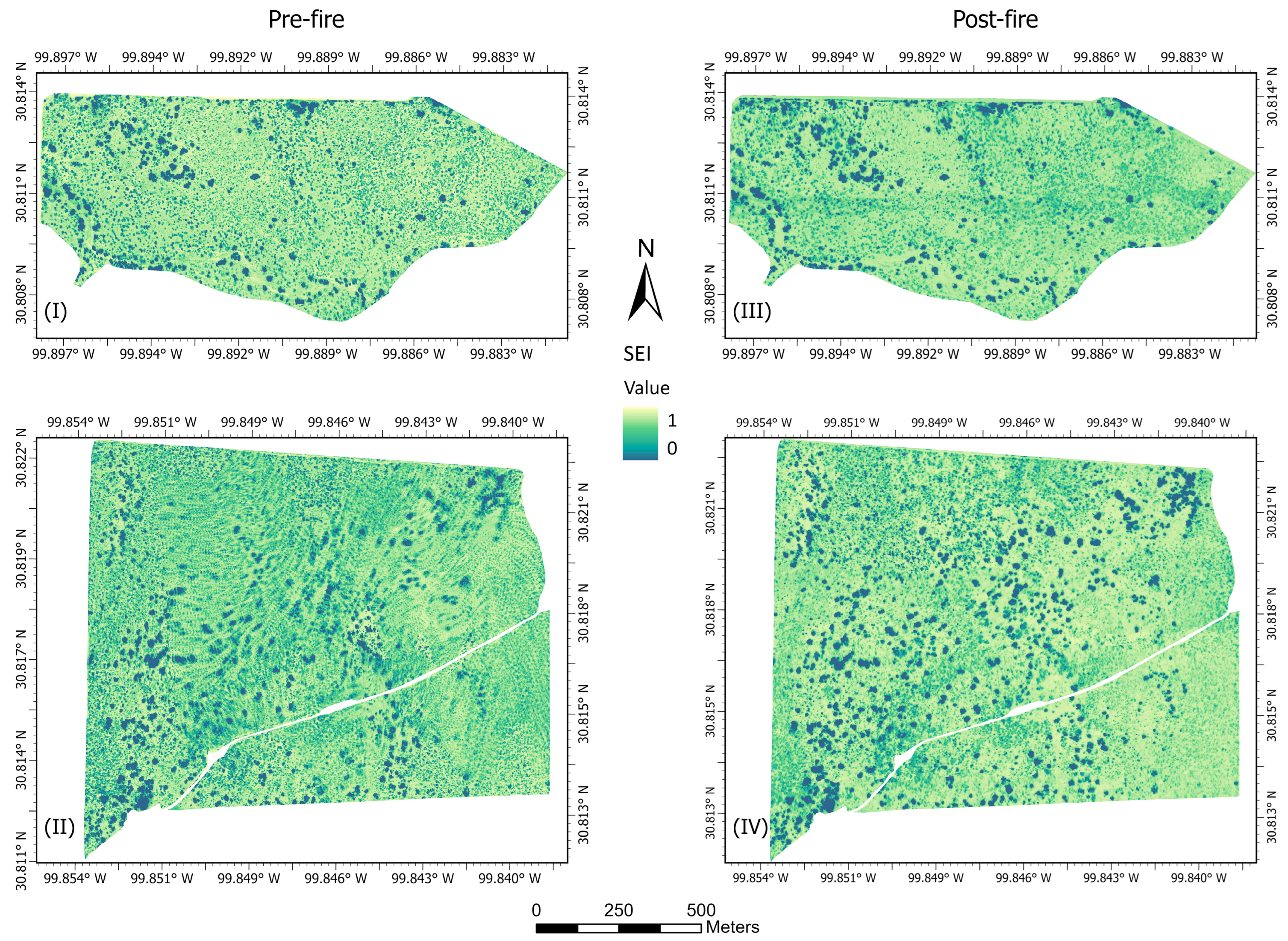

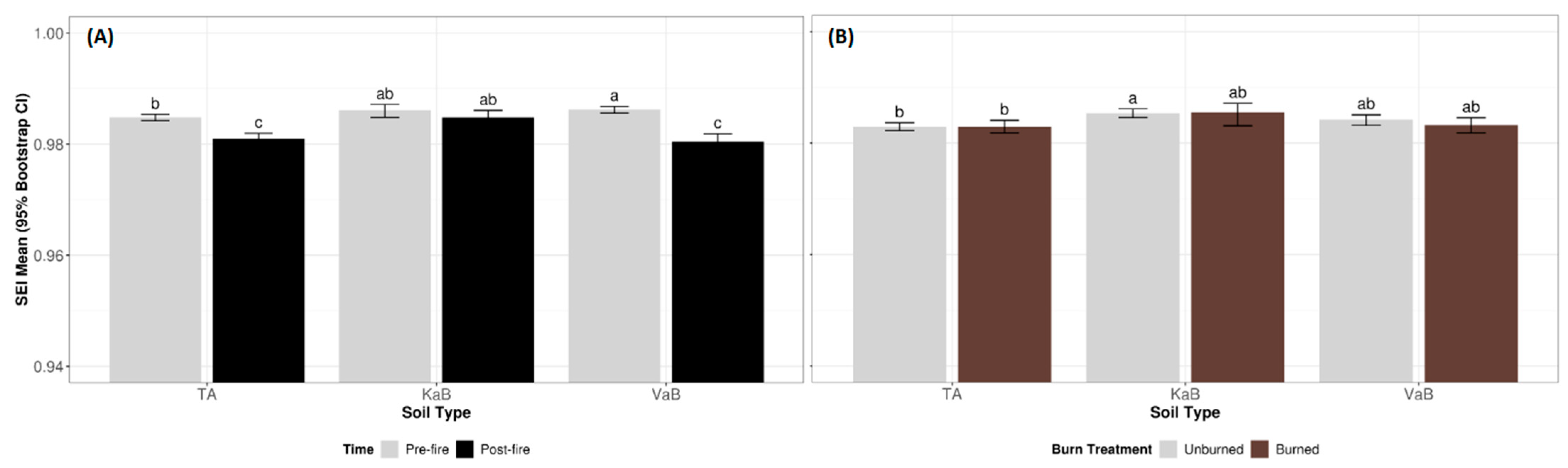

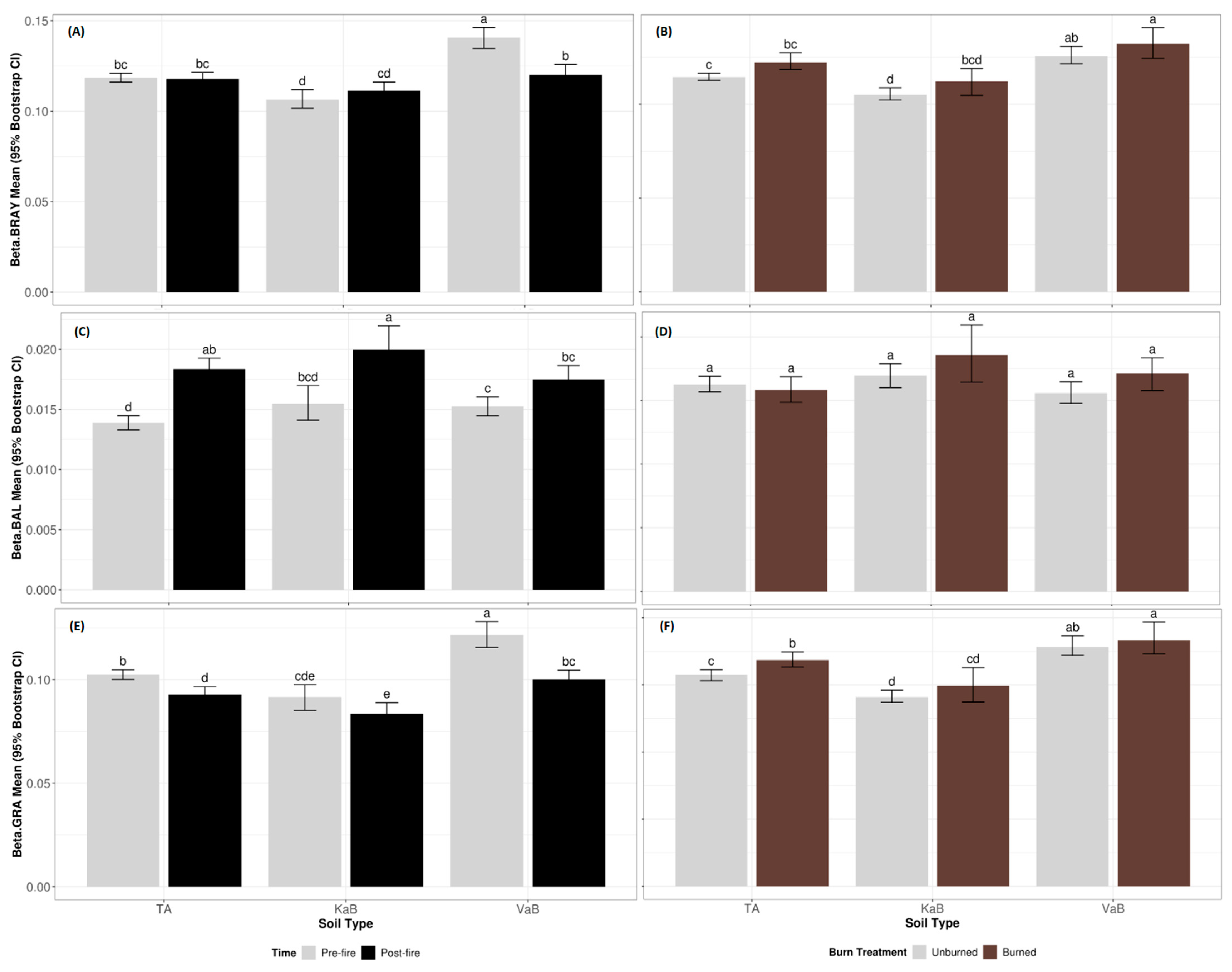

3.1. Changes in Shannon’s Evenness and Abundance-Based β-Diversity from Vegetation Spectra

3.2. Pre-Fire and Post-Fire Spatial Patterns of Shannon’s Evenness and Abundance-Based β-Diversity

3.3. Effect of Fire on Spectral Functional Traits

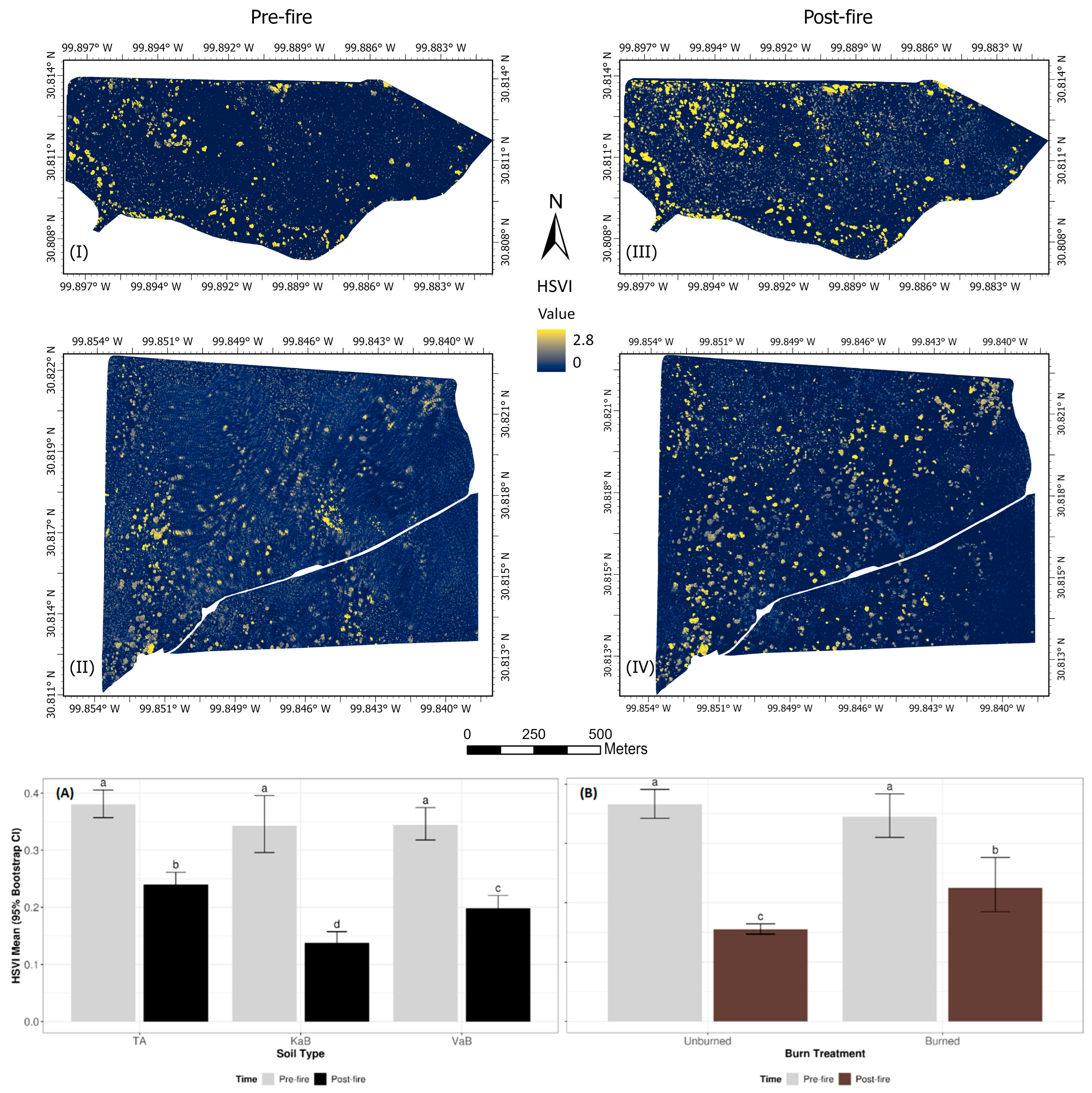

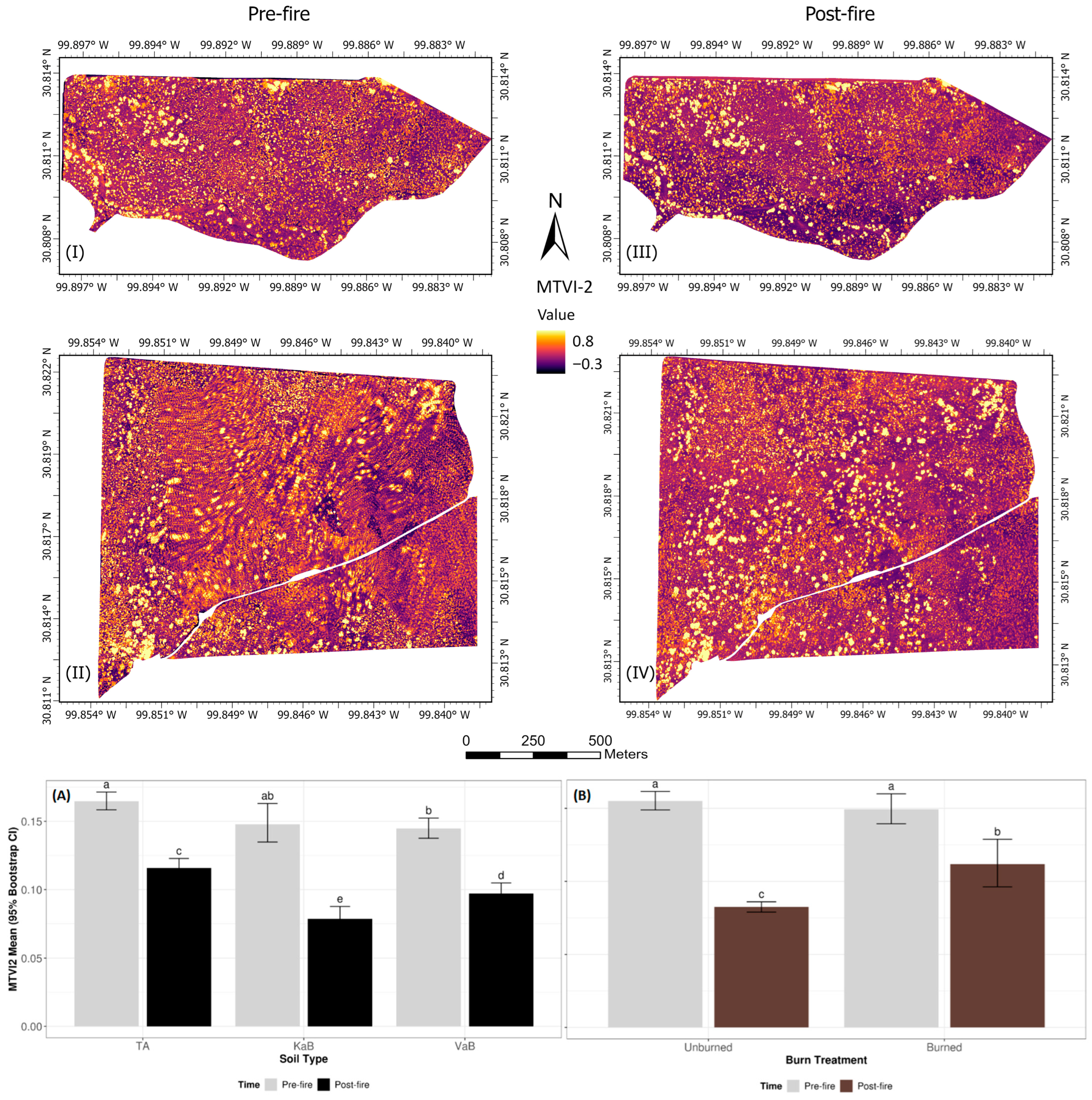

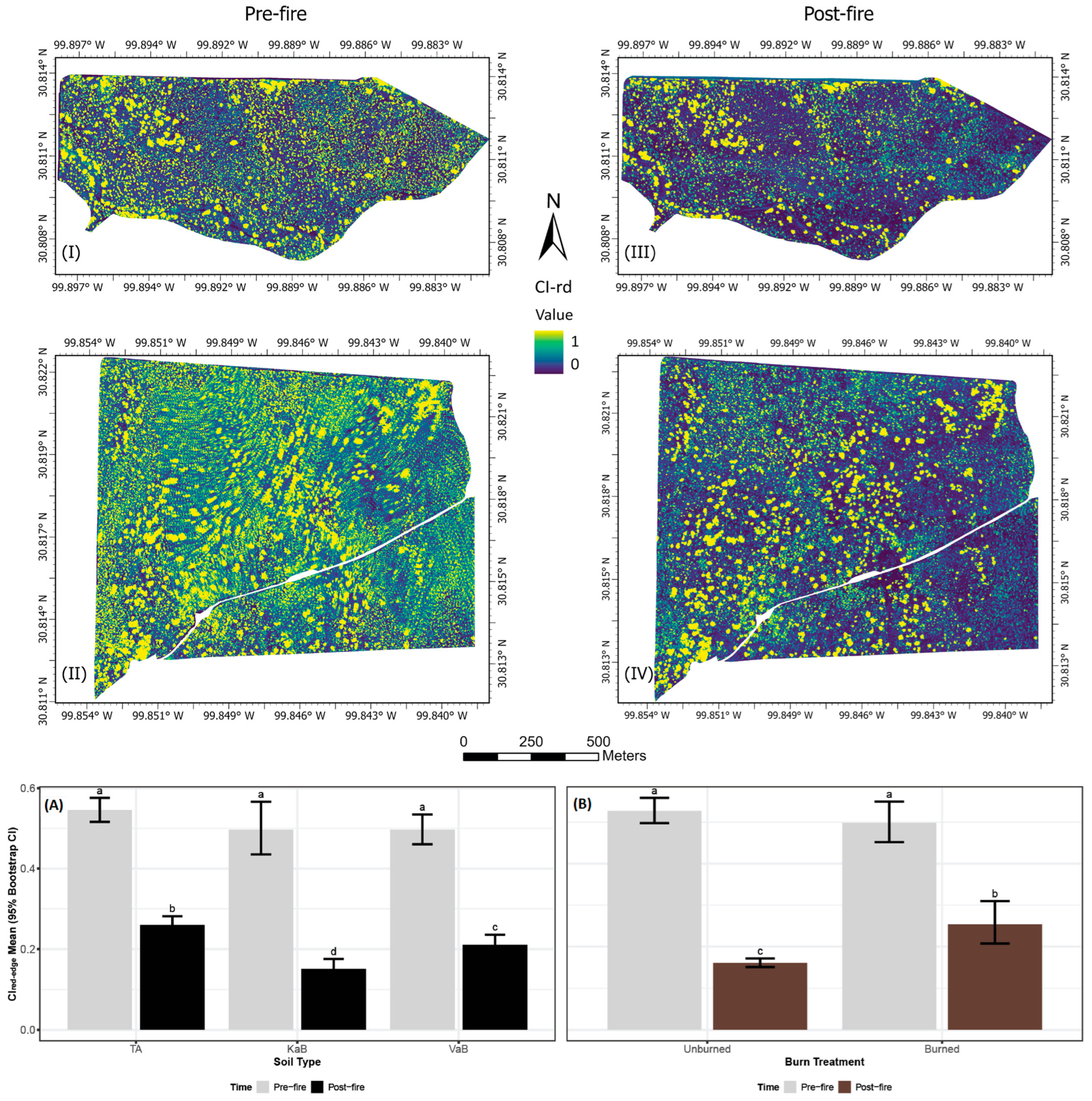

3.4. Pre-Fire and Post-Fire Spatial Patterns of Spectral Functional Traits

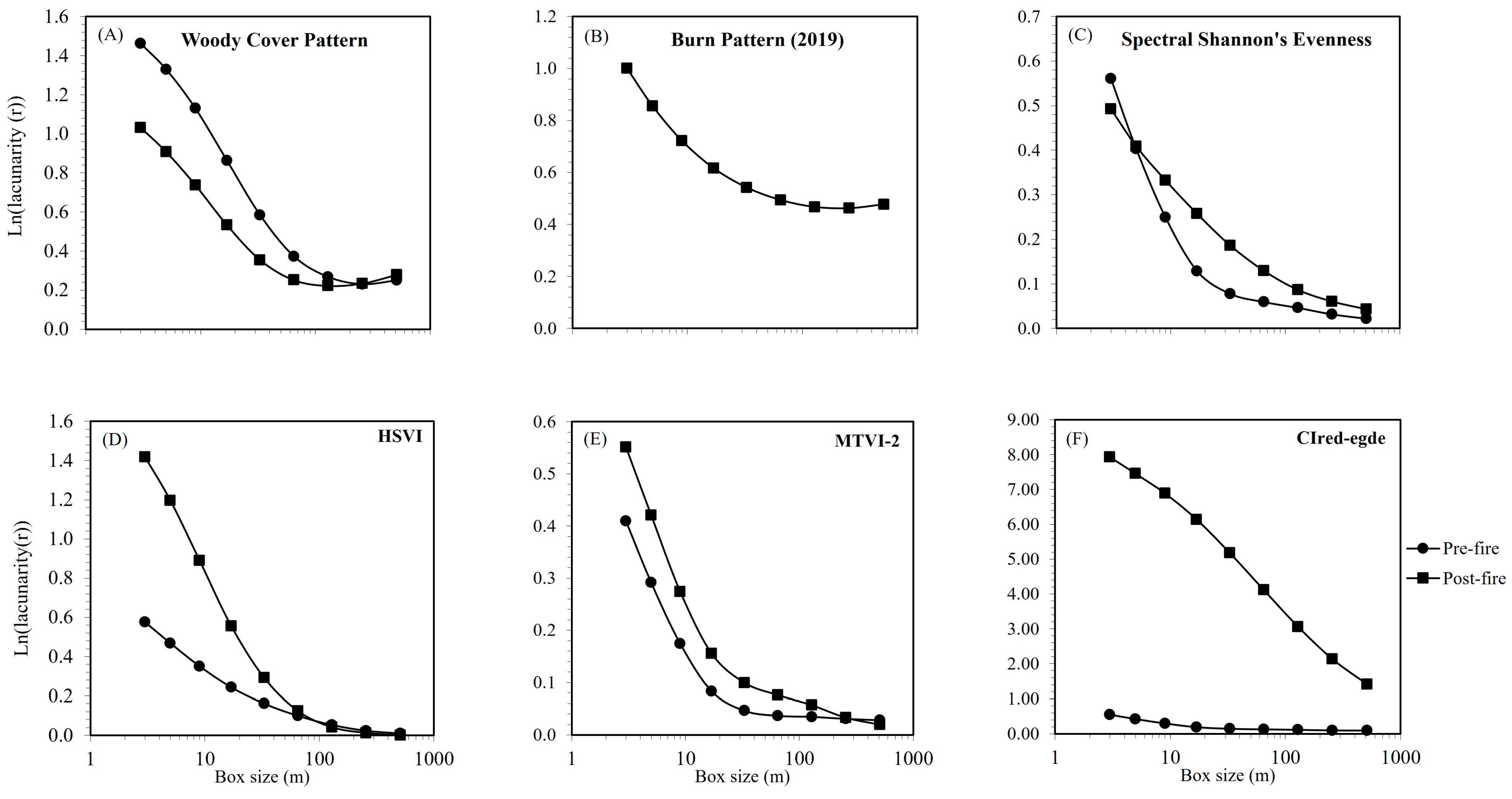

3.5. Multiscale Analysis of Heterogeneity of Vegetation Structure, Burn Pattern, Spectral Diversity, Functional Trait Indices

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Environmental Conditions Outweighted the Fire as Primary Drivert of Spectral Diversity Dynamics

4.2. Fire Influenced the Spatial Pattern of Spectral Evenness and Abundance-Based β-Diversity

4.3. Biophysical and Biochemical Spectral Indices Responded Primarily to Time and Weather-Driven Dry-Down Across Soils, with Some Moderation by Fire

4.4. Fire Significantly Influenced the Spatial Pattern of Spectral Indices Representative of Plant Functional Traits

4.5. Fire and Weather Altered the Scale-Dependent Spatial Heterogeneity of Spectral Evenness and Spectral Indices Representing Plant Functional Traits

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Multispectral Image Classification for Vegetation and Burn Cover Maps

| Classified data | Bare Ground | Woody | Non-Woody | Row Totals | User’s Accuracy (%) | |

| Bare Ground | 970 | 30 | 20 | 1020 | 95.1 | |

| Woody | 25 | 1580 | 43 | 1648 | 95.9 | |

| Non-Woody | 35 | 45 | 1081 | 1161 | 93.1 | |

| Column Totals | 1030 | 1655 | 1144 | 3829 | ||

| Producer’s Accuracy (%) | 94.2 | 95.5 | 94.5 | OA (94.8%) K (92.0%) |

| Classified data | Reference Data | ||||||

| Bare Ground | Non-Woody | Woody | Burn | Row Totals | User’s Accuracy (%) | ||

| Bare Ground | 998 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 1020 | 97.8 | |

| Non-Woody | 10 | 1091 | 128 | 75 | 1304 | 83.7 | |

| Woody | 0 | 48 | 1472 | 0 | 1520 | 96.8 | |

| Burn | 17 | 58 | 0 | 1054 | 1129 | 93.4 | |

| Column Totals | 1025 | 1209 | 1600 | 1139 | 4973 | ||

| Producer’s Accuracy (%) | 97.4 | 90.2 | 92.0 | 92.5 | OA (92.8%) K (90.3%) | ||

Appendix A.2. Sampling Procedure for Spectrally Sampled Locations

| UNIT | Categories | Hectares | %Area | Samples | Allowed Minimal Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lively | TA-Burn | 15.11 | 0.161 | 161 | 10 |

| Lively | TA-Unburn | 22.43 | 0.239 | 239 | 5 |

| Lively | VaB-Burn | 20.49 | 0.219 | 219 | 10 |

| Lively | VaB-Unburn | 20.96 | 0.224 | 224 | 5 |

| E6M | TA-Burn | 33.45 | 0.226 | 226 | 10 |

| E6M | TA-Unburn | 78.45 | 0.531 | 531 | 5 |

| E6M | KaB-Burn | 14.29 | 0.097 | 97 | 10 |

| E6M | KaB-Unburn | 21.45 | 0.145 | 145 | 5 |

| Lively | Overall | 93.71 | 1.00 | 843 | |

| E6M | Overall | 147.72 | 1.00 | 999 |

References

- Dahlin, K.M. Spectral Diversity Area Relationships for Assessing Biodiversity in a Wildland–Agriculture Matrix. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 2758–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.T.; Ostrovsky, M. From Space to Species: Ecological Applications for Remote Sensing. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeck, C.A.; Harms, K.E.; Yavitt, J.B.; John, R.; Turner, B.L.; Valencia, R.; Navarrete, H.; Davies, S.J.; Chuyong, G.B.; Kenfack, D.; et al. Soil Resources and Topography Shape Local Tree Community Structure in Tropical Forests. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldeck, C.A.; Colgan, M.S.; Féret, J.-B.; Levick, S.R.; Martin, R.E.; Asner, G.P. Landscape-scale Variation in Plant Community Composition of an African Savanna from Airborne Species Mapping. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, L.; Cho, M.A.; Mathieu, R.; Asner, G. Classification of Savanna Tree Species, in the Greater Kruger National Park Region, by Integrating Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data in a Random Forest Data Mining Environment. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2012, 69, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gamon, J.A.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Townsend, P.A.; Zygielbaum, A.I. The Spatial Sensitivity of the Spectral Diversity-Biodiversity Relationship: An Experimental Test in a Prairie Grassland. Ecol. Appl. Publ. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2018, 28, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Kneubühler, M.; Schütz, M.; Schaepman, M.E.; Haller, R.M.; Risch, A.C. Spatial Resolution, Spectral Metrics and Biomass Are Key Aspects in Estimating Plant Species Richness from Spectral Diversity in Species-rich Grasslands. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 8, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresani, M.; Rossi, C.; Perrone, M.; Hauser, L.T.; Féret, J.; Moudrý, V.; Simova, P.; Ricotta, C.; Foody, G.M.; Kacic, P.; et al. Reviewing the Spectral Variation Hypothesis: Twenty Years in the Tumultuous Sea of Biodiversity Estimation by Remote Sensing. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbin, S.P.; Singh, A.; McNeil, B.E.; Kingdon, C.C.; Townsend, P.A. Spectroscopic Determination of Leaf Morphological and Biochemical Traits for Northern Temperate and Boreal Tree Species. Ecol. Appl. 2014, 24, 1651–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, A.K.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Townsend, P.A.; Hobbie, S.E.; Madritch, M.D.; Wang, R.; Tilman, D.; Gamon, J.A. Plant Spectral Diversity Integrates Functional and Phylogenetic Components of Biodiversity and Predicts Ecosystem Function. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Schweiger, A.K.; Gamon, J.A.; Gholizadeh, H.; Helzer, K.; Lapadat, C.; Madritch, M.D.; Townsend, P.A.; Wang, Z.; Hobbie, S.E. Remotely Detected Aboveground Plant Function Predicts Belowground Processes in Two Prairie Diversity Experiments. Ecol. Monogr. 2022, 92, 01488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, F.E.; Müllerová, J.; Conti, L.; Malavasi, M.; Schmidtlein, S. About the Link between Biodiversity and Spectral Variation. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2022, 25, 12643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Malavasi, M.; Galland, T.; Komárek, J.; Lagner, O.; Carmona, C.P.; Rocchini, D.; Šímová, P. The Relationship between Species and Spectral Diversity in Grassland Communities Is Mediated by Their Vertical Complexity. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2021, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.W.; Earls, P.G.; Hoagland, B.W.; White, P.S.; Wohlgemuth, T. Quantitative tools for perfecting species lists. Environmetrics 2002, 13, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Balkenhol, N.; Carter, G.A.; Foody, G.M.; Gillespie, T.W.; He, K.S.; Kark, S.; Levin, N.; Lucas, K.; Luoto, M.; et al. Remotely Sensed Spectral Heterogeneity as a Proxy of Species Diversity: Recent Advances and Open Challenges. Ecol. Inform. 2010, 5, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; McGlinn, D.; Ricotta, C.; Neteler, M.; Wohlgemuth, T. Landscape Complexity and Spatial Scale Influence the Relationship between Remotely Sensed Spectral Diversity and Survey-Based Plant Species Richness. J. Veg. Sci. 2011, 22, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornley, R.H.; Gerard, F.F.; White, K.; Verhoef, A. Prediction of Grassland Biodiversity Using Measures of Spectral Variance: A Meta-Analytical Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberté, E.; Schweiger, A.K.; Legendre, P. Partitioning Plant Spectral Diversity into Alpha and Beta Components. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gamon, J.A. Remote sensing of terrestrial plant biodiversity. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Bacaro, G.; Chirici, G.; Re, D.; Feilhauer, H.; Foody, G.M.; Galluzzi, M.; Garzon-Lopez, C.X.; Gillespie, T.W.; He, K.S.; et al. Remotely Sensed Spatial Heterogeneity as an Exploratory Tool for Taxonomic and Functional Diversity Study. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Bai, Y. The Potential of Mapping Grassland Plant Diversity with the Links among Spectral Diversity, Functional Trait Diversity, and Species Diversity. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaraj, N.P.; Gholizadeh, H.; Hamilton, R.G.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Gamon, J.A. Estimating Plant β-Diversity Using Airborne and Spaceborne Imaging Spectroscopy. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchini, D.; Boyd, D.S.; Féret, B.; Foody, G.M.; He, K.S.; Lausch, A.; Nagendra, H.; Wegmann, M.; Pettorelli, N. Satellite Remote Sensing to Monitor Species Diversity: Potential and Pitfalls. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gamon, J.A.; Schweiger, A.K.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Townsend, P.A.; Zygielbaum, A.I.; Kothari, S. Influence of Species Richness, Evenness, and Composition on Optical Diversity: A Simulation Study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 211, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chlus, A.; Geygan, R.; Ye, Z.; Zheng, T.; Singh, A.; Couture, J.J.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Kruger, E.L.; Townsend, P.A. Foliar Functional Traits from Imaging Spectroscopy across Biomes in Eastern North America. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneece, I.P.; Epstein, H.; Lerdau, M. Correlating Species and Spectral Diversities Using Hyperspectral Remote Sensing in Early-Successional Fields. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 3475–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Fan, M.; Bai, L.; Sang, W.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Z.; Tao, Z. Identification of the Best Hyperspectral Indices in Estimating Plant Species Richness in Sandy Grasslands. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.D.; Morsdorf, F.; Schmid, B.; Petchey, O.L.; Hueni, A.; Schimel, D.S.; Schaepman, M.E. Mapping Functional Diversity from Remotely Sensed Morphological and Physiological Forest Traits. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfenstein, I.S.; Schneider, F.D.; Schaepman, M.E.; Morsdorf, F. Assessing Biodiversity from Space: Impact of Spatial and Spectral Resolution on Trait-Based Functional Diversity. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 275, 113024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violle, C.; Navas, M.; Vile, D.; Kazakou, E.; Fortunel, C.; Hummel, I.; Garnier, É. Let the Concept of Trait Be Functional! Oikos 2007, 116, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, F.; Fu, H.; Li, Z. Hyperspectral Image-Based Vegetation Index (HSVI): A New Vegetation Index for Urban Ecological Research. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 103, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T.; Huete, A.R.; Yoshioka, H.; Holben, B.N. An Error and Sensitivity Analysis of Atmospheric Resistant Vegetation Indices Derived from Dark Target-Based Atmospheric Correction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 78, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, B. Chlorophyll: Structure and Function. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, K.M.; Stone, C.; Mohammed, C.L. Crown-scale Evaluation of Spectral Indices for Defoliated and Discoloured Eucalypts. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between Leaf Chlorophyll Content and Spectral Reflectance and Algorithms for Non-Destructive Chlorophyll Assessment in Higher Plant Leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briske, D.D.; Coppock, D.L. Rangeland Stewardship Envisioned through a Planetary Lens. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briske, D.D.; Archer, S.R.; Burchfield, E.; Burnidge, W.; Derner, J.D.; Gosnell, H.; Hatfield, J.; Kazanski, C.E.; Khalil, M.; Lark, T.J.; et al. Supplying ecosystem services on US rangelands. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.; Perry, G.L.; Higgins, S.I.; Johnson, C.N.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Murphy, B.P. Pyrodiversity Is the Coupling of Biodiversity and Fire Regimes in Food Webs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, D.A.; Hovick, T.J.; Elmore, R.D.; Engle, D.M.; Fuhlendorf, S.D. Moderate Patchiness Optimizes Heterogeneity, Stability, and Beta Diversity in Mesic Grassland. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 5008–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Engle, D.M.; Kerby, J.; Hamilton, R. Pyric Herbivory: Rewilding Landscapes through the Recoupling of Fire and Grazing. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhlendorf, S.; Fynn, R.; McGranahan, D.; Twidwell, D. Heterogeneity as the Basis for Rangeland Management. In Rangeland Systems: Processes, Management and Challenges; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-46707-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Engle, D.M. Application of the Fire–Grazing Interaction to Restore a Shifting Mosaic on Tallgrass Prairie. J. Appl. Ecol. 2004, 41, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limb, R.F.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Engle, D.M.; Weir, J.R.; Elmore, R.D.; Bidwell, T.G. Pyric–Herbivory and Cattle Performance in Grassland Ecosystems. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 64, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, D.; Engle, D.; Fuhlendorf, S.; Winter, S.; Miller, J.; Debinski, D. Inconsistent Outcomes of Heterogeneity-Based Management Underscore Importance of Matching Evaluation to Conservation Objectives. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 31, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhlendorf, S.; Davis, C.; Elmore, R.; Goodman, L.; Hamilton, R. Perspectives on Grassland Conservation Efforts: Should We Rewild to the Past or Conserve for the Future? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerby, J.; Fuhlendorf, S.; Engle, D. Landscape Heterogeneity and Fire Behavior: Scale-Dependent Feedback between Fire and Grazing Processes. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Fuhlendorf, S.; Goad, C.; Davis, C.; Hickman, K. Topoedaphic Variability and Patch Burning in Sand Sagebrush Shrubland. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 64, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, B.P.; Birt, A.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Archer, S.R. Emerging Frameworks for Understanding and Mitigating Woody Plant Encroachment in Grassy Biomes. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 32, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime Davila, X.A. Spatial Patterns and Interactions of Prescribed Fire and Plant Communities in Heterogeneous Landscapes in the Edwards Plateau. Ph.D. Dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Staff Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) Database. Available online: https://sdmdataaccess.sc.egov.usda.gov (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- PRISM Group. PRISM Gridded Climate Data; Oregon State University: Corvallis, Oregon, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abatzoglou, J.T. Development of Gridded Surface Meteorological Data for Ecological Applications and Modelling. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime, X.A.; Angerer, J.P.; Yang, C.; Walker, J.; Mata, J.; Tolleson, D.R.; Wu, X.B. Exploring Effective Detection and Spatial Pattern of Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia Genus) from Airborne Imagery before and after Prescribed Fires in the Edwards Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime, X.A.; Angerer, J.P.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Walker, J.W.; Yang, C.; Tolleson, D.R.; Wu, X.B. Effects of Prescribed Fire on Plant α- and ꞵ-Diversity and the Regulating Role of Soil in a Mesquite-Oak Savanna. Landsc. Ecol. 2025, 40, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, J.R.; Salvaggio, C.; Volchok, W.J. Radiometric Scene Normalization Using Pseudoinvariant Features. Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, F.G.; Strebel, D.E.; Nickeson, J.E.; Goetz, S.J. Radiometric Rectification: Toward a Common Radiometric Response among Multidate, Multisensor Images. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 35, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J. Terra: Spatial Data Analysis, Version 1.8-44. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/rspatial/terra (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Keydan, G.P.; Merzlyak, M.N. Three-Band Model for Noninvasive Estimation of Chlorophyll, Carotenoids, and Anthocyanin Contents in Higher Plant Leaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L11402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J. Raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/rspatial/raster (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Izrailev, S. Tictoc: Functions for Timing R Scripts, as Well as Implementations of “Stack” and “StackList”, version 1. Structures R Package Version. 2023. Available online: https://jabiru.github.io/tictoc/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, Version 2.7-2. 2024. Available online: https://vegandevs.github.io/vegan/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Baselga, A. Separating the Two Components of Abundance-based Dissimilarity: Balanced Changes in Abundance vs. Abundance Gradients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnick, R.; Gardner, R.; Hargrove, W.; Prestegaard, K.; Perlmutter, M. Lacunarity Analysis: A General Technique for the Analysis of Spatial Patterns. Phys. Rev. E 1996, 53, 5461–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.B.; Thurow, T.L.; Whisenant, S.G. Fragmentation and Changes in Hydrologic Function of Tiger Bush Landscapes, South-West Niger. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.B.; Sui, D.Z. An Initial Exploration of a Lacunarity-Based Segregation Measure. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2001, 28, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derner, J.D.; Wu, X.B. Light Distribution in Mesic Grasslands: Spatial Patterns and Temporal Dynamics. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2001, 4, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S.T. spatLac: R Package for Computing Lacunarity for Spatial Raster. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5786547 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Allain, C.; Cloitre, M. Characterizing the Lacunarity of Random and Deterministic Fractal Sets. Phys. Rev. A 1991, 44, 3552–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P. Lacunarity for Spatial Heterogeneity Measurement in GIS. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2000, 6, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagin, R.A. Heterogeneity Versus Homogeneity: A Conceptual and Mathematical Theory in Terms of Scale-Invariant and Scale-Covariant Distributions. Ecol. Complex. 2005, 2, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoechstetter, S.; Walz, U.; Thinh, N. Adapting Lacunarity Techniques for Gradient-Based Analyses of Landscape Surfaces. Ecol. Complex. 2011, 8, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.D. Detection of Influential Observation in Linear Regression. Technometrics 1977, 19, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Statistics and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-387-95457-8. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A. Finding Optimal Normalizing Transformations via bestNormalize. R J. 2021, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Cavanaugh, J.E. Ordered Quantile Normalization: A Semiparametric Transformation Built for the Cross-Validation Era. J. Appl. Stat. 2020, 47, 2312–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V.; Piaskowski, J. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package Version 2.0.0. 2017. Available online: https://rvlenth.github.io/emmeans/ (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Baselga, A.; Orme, C.D.L. Betapart: An R Package for the Study of Beta Diversity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Mitsch, W.J. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Algae in Newly Constructed Freshwater Wetlands. Wetlands 1998, 18, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Fortin, M.-J. Comparison of the Mantel Test and Alternative Approaches for Detecting Complex Multivariate Relationships in the Spatial Analysis of Genetic Data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thioulouse, J.; Dray, S.; Dufour, A.; Siberchicot, A.; Jombart, T.; Pavoine, S. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data with Ade4; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, S.; Dufour, A.; Chessel, D. The Ade4 Package—II: Two-Table and K-Table Methods. R News 2007, 7, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, S.; Bauman, D.; Blanchet, G.; Borcard, D.; Clappe, S.; Guénard, G.; Jombart, T.; Larocque, G.; Legendre, P.; Madi, N.; et al. Adespatial: Multivariate Multiscale Spatial Analysis. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=adespatial (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Bivand, R. R Packages for Analyzing Spatial Data: A Comparative Case Study with Areal Data. Geogr. Anal. 2022, 54, 488–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabot, J.; Clappe, S.; Dray, S.; Datry, T. Testing the Mantel Statistic with a Spatially-Constrained Permutation Procedure. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, P. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2024. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. In R; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, D.M.; Germino, M.J.; Bradford, J.B.; O’Connor, R.C.; Andrews, C.M.; Shriver, R.K. Are Drought Indices and Climate Data Good Indicators of Ecologically Relevant Soil Moisture Dynamics in Drylands? Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, P.J.; Steiner, J.L.; Neel, J.P.S.; Turner, K.E.; Northup, B.K.; Gowda, P.H.; Brown, M.A. Assessment of the Standardized Precipitation and Evaporation Index (SPEI) as a Potential Management Tool for Grasslands. Agronomy 2019, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sotoca, J.J.; Sanz, E.; Saa-Requejo, A.; Moratiel, R.; Almeida-Ñauñay, A.F.; Tarquis, A.M. Relationship between Vegetation and Soil Moisture Anomalies Based on Remote Sensing Data: A Semiarid Rangeland Case. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, Q.; Liu, B.; Chen, H. Exploring the Relationship between Vegetation Spectra and Eco-Geo-Environmental Conditions in Karst Region, Southwest China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 160, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twidwell, D.; Wonkka, C.L.; Taylor, C.A.; Zou, C.B.; Twidwell, J.J.; Rogers, W.E. Drought-induced Woody Plant Mortality in an Encroached Semi-arid Savanna Depends on Topoedaphic Factors and Land Management. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2014, 17, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.; Silva, J.M.; Cerasoli, S. Spectral-Based Monitoring of Climate Effects on the Inter-Annual Variability of Different Plant Functional Types in Mediterranean Cork Oak Woodlands. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastro, L.A.; Dickman, C.R.; Letnic, M. Burning for Biodiversity or Burning Biodiversity? Prescribed Burn vs. Wildfire Impacts on Plants, Lizards, and Mammals. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 3238–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Ramirez, A.; Salas-Eljatib, C.; González, M.E.; Urrutia-Estrada, J.; Arroyo-Vargas, P.; Santibañez, P. Initial Response of Understorey Vegetation and Tree Regeneration to a Mixed-Severity Fire in Old-Growth Araucaria–Nothofagus Forests. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2020, 23, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Quiring, S.M.; Zhao, C. Evaluating the Utility of Drought Indices as Soil Moisture Proxies for Drought Monitoring and Land–Atmosphere Interactions. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 2157–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Han, K.; Hong, S.; Park, N.; Lee, Y.; Cho, J. Satellite-Based Evaluation of the Post-Fire Recovery Process from the Worst Forest Fire Case in South Korea. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudnikova, E.; Savin, I.; Vindeker, G.; Grubina, P.; Shishkonakova, E.; Sharychev, D. Influence of Soil Background on Spectral Reflectance of Winter Wheat Crop Canopy. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraverbeke, S.; Somers, B.; Gitas, I.; Katagis, T.; Polychronaki, A.; Goossens, R. Spectral Mixture Analysis to Assess Post-Fire Vegetation Regeneration Using Landsat Thematic Mapper Imagery: Accounting for Soil Brightness Variation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, R.J.; Pinchak, W.E. Stability of C3 and C4 Grass Patches in Woody Encroached Rangeland after Fire and Simulated Grazing. Diversity 2023, 15, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masunga, G.S.; Moe, S.R.; Pelekekae, B. Fire and Grazing Change Herbaceous Species Composition and Reduce Beta Diversity in the Kalahari Sand System. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeire, L.T.; Mitchell, R.B.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Gillen, R.L. Patch Burning Effects on Grazing Distribution. J. Range Manag. 2004, 57, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, B.W.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Engle, D.M.; Elmore, R.D. Ungulate Preference for Burned Patches Reveals Strength of Fire–Grazing Interaction. Ecol. Evol. 2011, 1, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiess, J.W.; McGranahan, D.A.; Berti, M.T.; Gasch, C.K.; Hovick, T.; Geaumont, B. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Rangeland Forage Nutritive Value and Grazer Selection with Patch-Burning in the US Northern Great Plains. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahood, A.L.; Balch, J.K. Repeated Fires Reduce Plant Diversity in Low-Elevation Wyoming Big Sagebrush Ecosystems (1984–2014. Ecosphere 2019, 10, 02591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.J.; Midgley, G.F.; Woodward, F.I. The Importance of Low Atmospheric CO2 and Fire in Promoting the Spread of Grasslands and Savannas. Glob. Change Biol. 2003, 9, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, R.J.; Wiedemann, H.T.; Castellano, M.J.; Slosser, J.E. Herbaceous Restoration of Juniper Dominated Grasslands With Chaining and Fire. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 59, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, R.J.; Boutton, T.W.; Mirik, M.; Castellano, M.J.; Kramp, B.A. Restoration of C4 Grasses with Seasonal Fires in a C3/C4 Grassland Invaded by Prosopis glandulosa, a Fire-resistant Shrub. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2010, 13, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, R.J.; Moeller, A.K.; Fuhlendorf, S.D. Pyric-based Restoration of C4 Grasses in Woody (Prosopis glandulosa) Encroached Grassland Is Best with an Alternating Seasonal Fire Regime. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Auken, O.W. Shrub Invasions of North American Semiarid Grasslands. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, R.J.; Castellano, M.J. Prickly Pear Cactus Responses to Summer and Winter Fires. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 60, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.M.; Kolden, C.A.; Talhelm, A.F.; Smith, A.M.; Apostol, K.G.; Johnson, D.M.; Boschetti, L. Spectral Indices Accurately Quantify Changes in Seedling Physiology Following Fire: Towards Mechanistic Assessments of Post-Fire Carbon Cycling. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, W.T. Physiological Consequences of Moisture Deficit Stress in Cotton. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Candón, D.; Bellvert, J.; Royo, C. Performance of the Two-Source Energy Balance (Tseb) Model as a Tool for Monitoring the Response of Durum Wheat to Drought by High-Throughput Field Phenotyping. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 658357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certini, G. Effects of Fire on Properties of Forest Soils: A Review. Oecologia 2005, 143, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, D.G.; Klopatek, C.C.; DeBano, L.F.; Ffolliott, P.F. Fire Effects on Belowground Sustainability: A Review and Synthesis. For. Ecol. Manag. 1999, 122, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Hedin, L.O.; Staver, A.C.; Govender, N. Fire Alters Ecosystem Carbon and Nutrients but Not Plant Nutrient Stoichiometry or Composition in Tropical Savanna. Ecology 2015, 96, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Alonso, P.; Prats, S.A.; Merino, A.; Guiomar, N.; Guijarro, M.; Madrigal, J. Fire Enhances Changes in Phosphorus (P) Dynamics Determining Potential Post-Fire Soil Recovery in Mediterranean Woodlands. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.I.E.; Mehnaz, K.R.; Ellsworth, D.S. Stimulated Photosynthesis of Regrowth after Fire in Coastal Scrub Vegetation: Increased Water or Nutrient Availability? Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fultz, L.M.; Moore-Kucera, J.; Dathe, J.; Davinic, M.; Perry, G.; Wester, D.; Schwilk, D.W.; Rideout-Hanzak, S. Forest Wildfire and Grassland Prescribed Fire Effects on Soil Biogeochemical Processes and Microbial Communities: Two Case Studies in the Semi-Arid Southwest. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2016, 99, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knicker, H. How Does Fire Affect the Nature and Stability of Soil Organic Nitrogen and Carbon? A Review. Biogeochemistry 2007, 85, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokshin, A.; Palchan, D.; Gross, A. Direct Foliar Phosphorus Uptake from Wildfire Ash. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Gitelson, A.A. Remote Estimation of Crop and Grass Chlorophyll and Nitrogen Content Using Red-Edge Bands on Sentinel-2 and -3. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2013, 23, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, A.; Piqué, M.; Castellnou, M.; Brotons, L. Predictive Modelling of Fire Occurrences from Different Fire Spread Patterns in Mediterranean Landscapes. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2015, 24, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, E.; Sunar, F. Spatial Pattern Analysis of Post-Fire Damages in the Menderes District of Turkey. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 14, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staver, A.C.; Archibald, S.; Levin, S.A. The Global Extent and Determinants of Savanna and Forest as Alternative Biome States. Science 2011, 334, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, A.; Goldstein, G.; Franco, A.C.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Differential Seedling Establishment of Woody Plants along a Tree Density Gradient in Neotropical Savannas. J. Ecol. 2012, 100, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, H.; Dixon, A.P.; Pan, K.H.; McMillan, N.A.; Hamilton, R.G.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Gamon, J.A. Using Airborne and DESIS Imaging Spectroscopy to Map Plant Diversity across the Largest Contiguous Tract of Tallgrass Prairie on Earth. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 281, 113254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yang, C.; Wu, M.; Zhao, C.; Yang, G.; Hoffmann, W.C.; Huang, W. Evaluation of Sentinel-2A Satellite Imagery for Mapping Cotton Root Rot. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, C.; Huang, W.; Tang, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Q. Identification of Cotton Root Rot by Multifeature Selection from Sentinel-2 Images Using Random Forest. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Remote Sensing Technologies for Crop Disease and Pest Detection. In Soil and Crop Sensing for Precision Crop Production; Agriculture Automation and Control; Li, M., Yang, C., Zhang, Q., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 159–184. ISBN 978-3-030-70432-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R. Classes and methods for spatial data in R. R News 2005, 5, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiñán, O.; Hijmans, R. rasterVis. R package Version 0.51.7. 2025. Available online: https://oscarperpinan.codeberg.page/rastervis/ (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Richards, J.A. Remote Sensing Digital Image Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

| Spectral Index | Traits | Bands (nm) | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSVI 1 | Biophysical | 520, 689, 760, 861, 889 | |

| MTVI-2 2 | Biochemical Activity | 550, 670, 800 | |

| CIred-edge 3 | Biochemical Stress | 710, 780 |

| Mantel | SEI (r; p-val) | β.BRAY (r; p-val) | β.BAL (r; p-val) | β.GRA (r; p-val) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XpreD | 0.0155; <0.001 | 0.0559; <0.001 | 0.0050; 0.002 | 0.0569; <0.001 |

| XposD | 0.0067; <0.001 | 0.0075; <0.001 | 0.0134; <0.001 | 0.0146; <0.001 |

| XPreXPos | 0.3949; <0.001 | 0.0664; 0.005 | 0.3730; <0.001 | 0.0627; 0.002 |

| XposB | −0.1174; <0.001 | ns | ns | 0.0889; <0.001 |

| XposD.B | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Mantel | HSVI 1 (r; p-val) | MTVI-2 2 (r; p-val) | CIred-edge 3 (r; p-val) |

|---|---|---|---|

| XpreD | 0.0121; <0.001 | 0.0305; <0.001 | 0.0208; <0.001 |

| XposD | 0.0012; <0.001 | −0.0001; 0.002 | ns |

| XPreXPos | 0.3749; <0.001 | 0.3512; <0.001 | 0.0560; <0.001 |

| XposB | −0.0983; 0.046 | −0.1202; 0.023 | 0.1118; 0.039 |

| XposD.B | ns | ns | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaime, X.A.; Angerer, J.P.; Yang, C.; Tolleson, D.R.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Wu, X.B. Effects of Prescribed Fire on Spatial Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Spectral Diversity Using Hyperspectral Imagery from Savannah Landscapes on the Edwards Plateau of Texas, USA. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233873

Jaime XA, Angerer JP, Yang C, Tolleson DR, Fuhlendorf SD, Wu XB. Effects of Prescribed Fire on Spatial Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Spectral Diversity Using Hyperspectral Imagery from Savannah Landscapes on the Edwards Plateau of Texas, USA. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233873

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaime, Xavier A., Jay P. Angerer, Chenghai Yang, Douglas R. Tolleson, Samuel D. Fuhlendorf, and X. Ben Wu. 2025. "Effects of Prescribed Fire on Spatial Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Spectral Diversity Using Hyperspectral Imagery from Savannah Landscapes on the Edwards Plateau of Texas, USA" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233873

APA StyleJaime, X. A., Angerer, J. P., Yang, C., Tolleson, D. R., Fuhlendorf, S. D., & Wu, X. B. (2025). Effects of Prescribed Fire on Spatial Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Spectral Diversity Using Hyperspectral Imagery from Savannah Landscapes on the Edwards Plateau of Texas, USA. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233873