Remote Sensing Inversion and Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Multi-Depth Soil Salinity in a Typical Arid Wetland: A Case Study of Ebinur Wetland Reserve, Xinjiang

Highlights

- The study developed a multi-depth (0–100 cm) soil salinity inversion framework based on the CNN combined with RFLA, effectively capturing spatial heterogeneity of salinization in arid regions.

- The CNN model demonstrated superior accuracy compared with RF and LSTM models, highlighting its advantage in spatial feature extraction for multi-depth salinity mapping.

- The proposed framework provides a practical and scalable approach for high-accuracy salinity monitoring in arid and semi-arid regions, supporting sustainable agricultural and ecological management.

- The multi-depth inversion results reveal vertical migration patterns of soil salinity, offering new insights into subsurface salt accumulation processes and long-term salinization dynamics.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Field Sampling and Data Acquisition

2.2.2. Landsat Series Remote Sensing Image Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Selection of Spectral Indices

2.3.2. Random Frog Leaping Algorithm (RFLA)

2.3.3. Selection of Soil Salinity Inversion Models

- (1)

- Random Forest (RF)

- (2)

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- (3)

- Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM)

2.3.4. Accuracy Validation

2.3.5. Sen’s Slope and Mann–Kendall (MK) Trend Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Soil Salinity

3.2. Selection of Characteristic Variables for Soil Salinity

3.3. Comparison of Soil Salinity Inversion Models

3.4. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Soil Salinity in the Ebinur Wetland Reserve

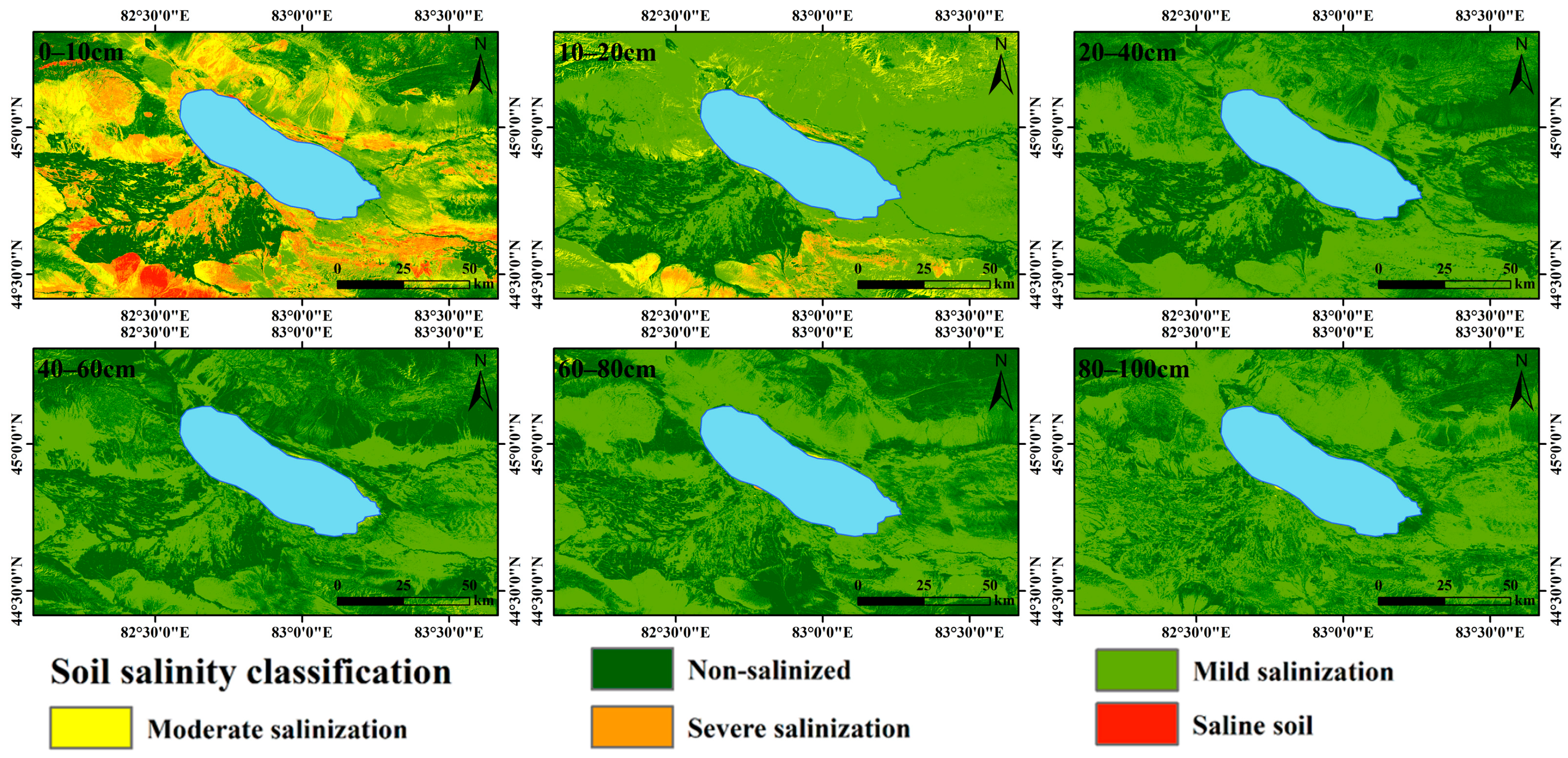

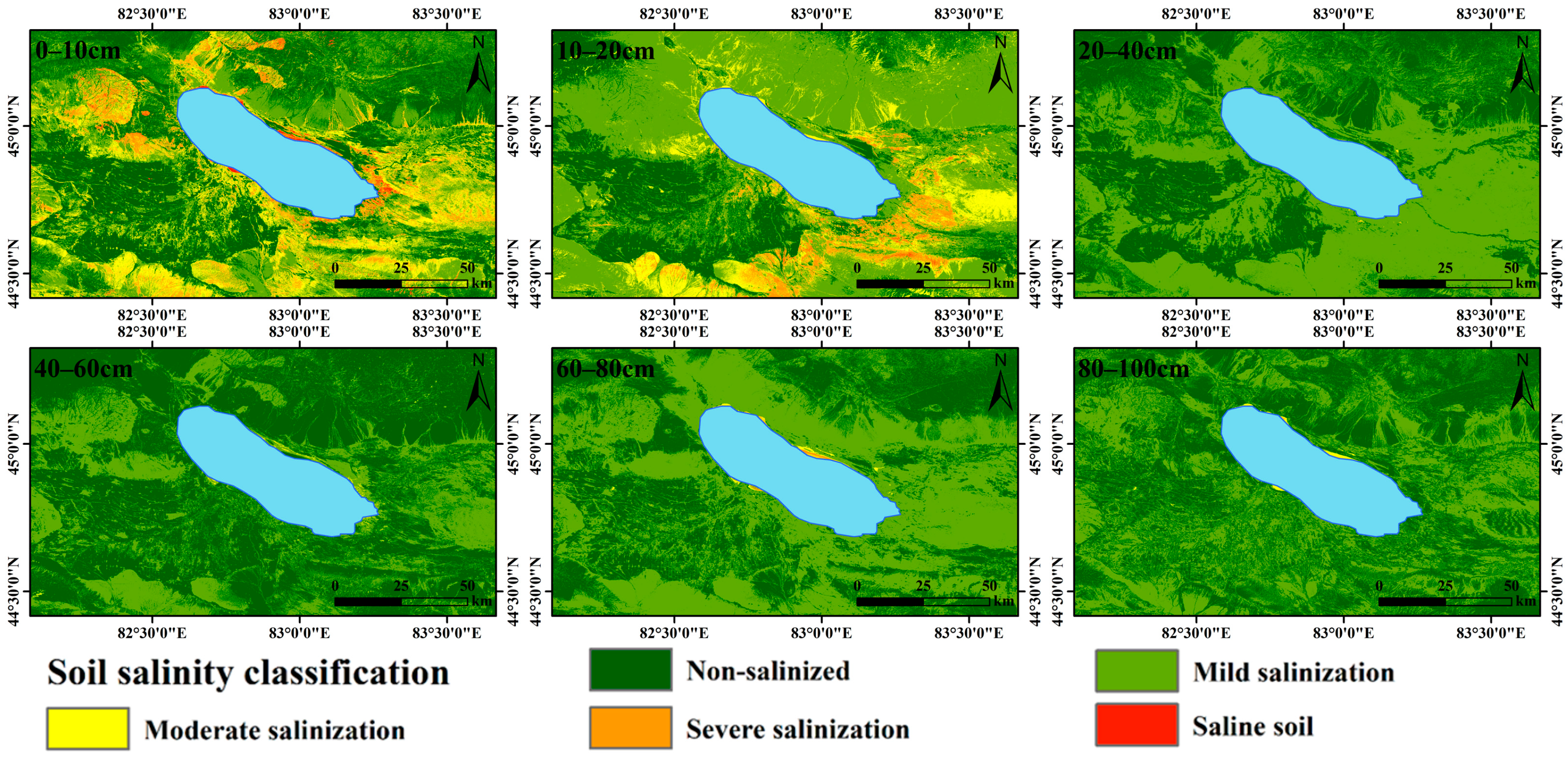

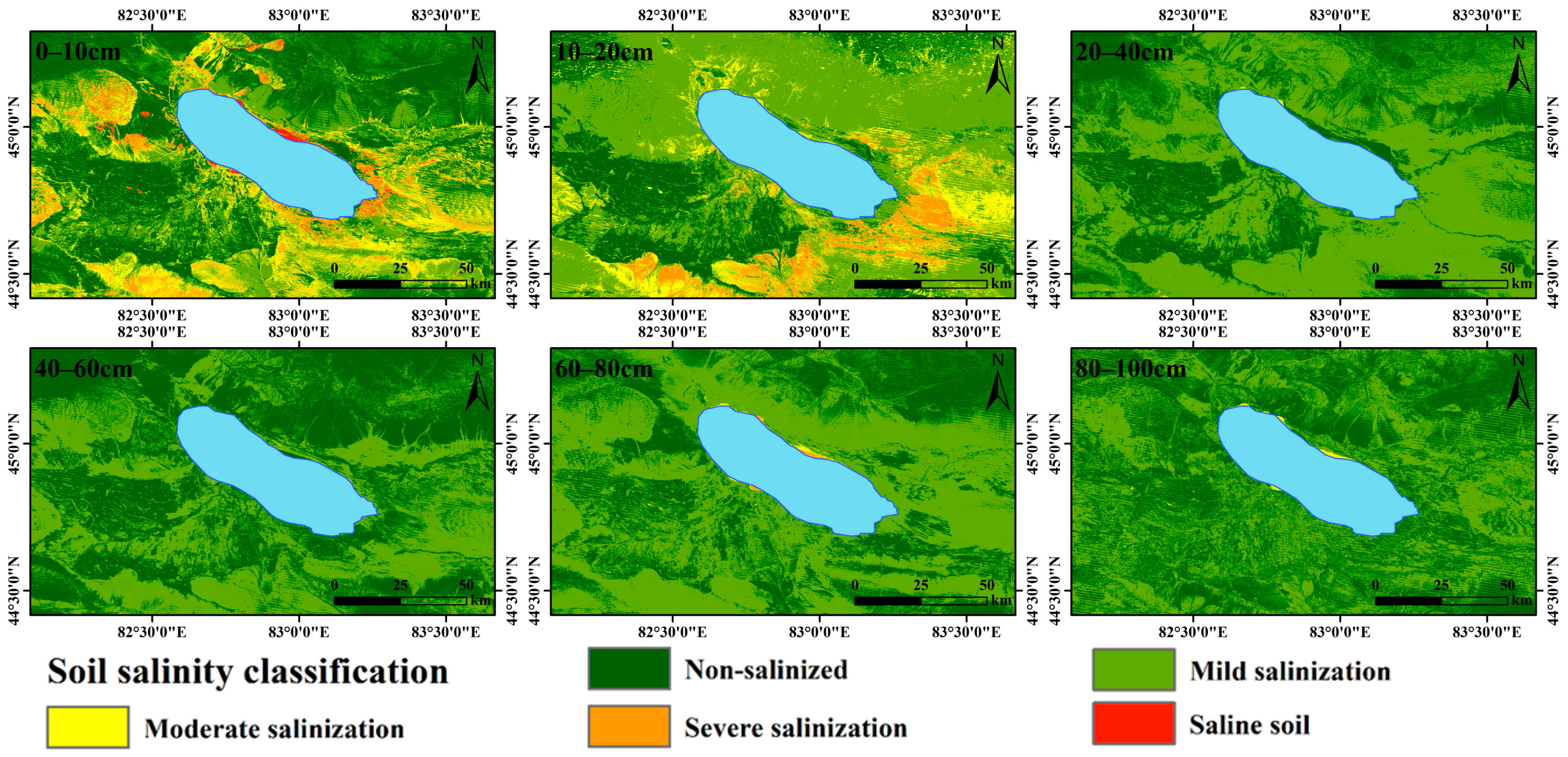

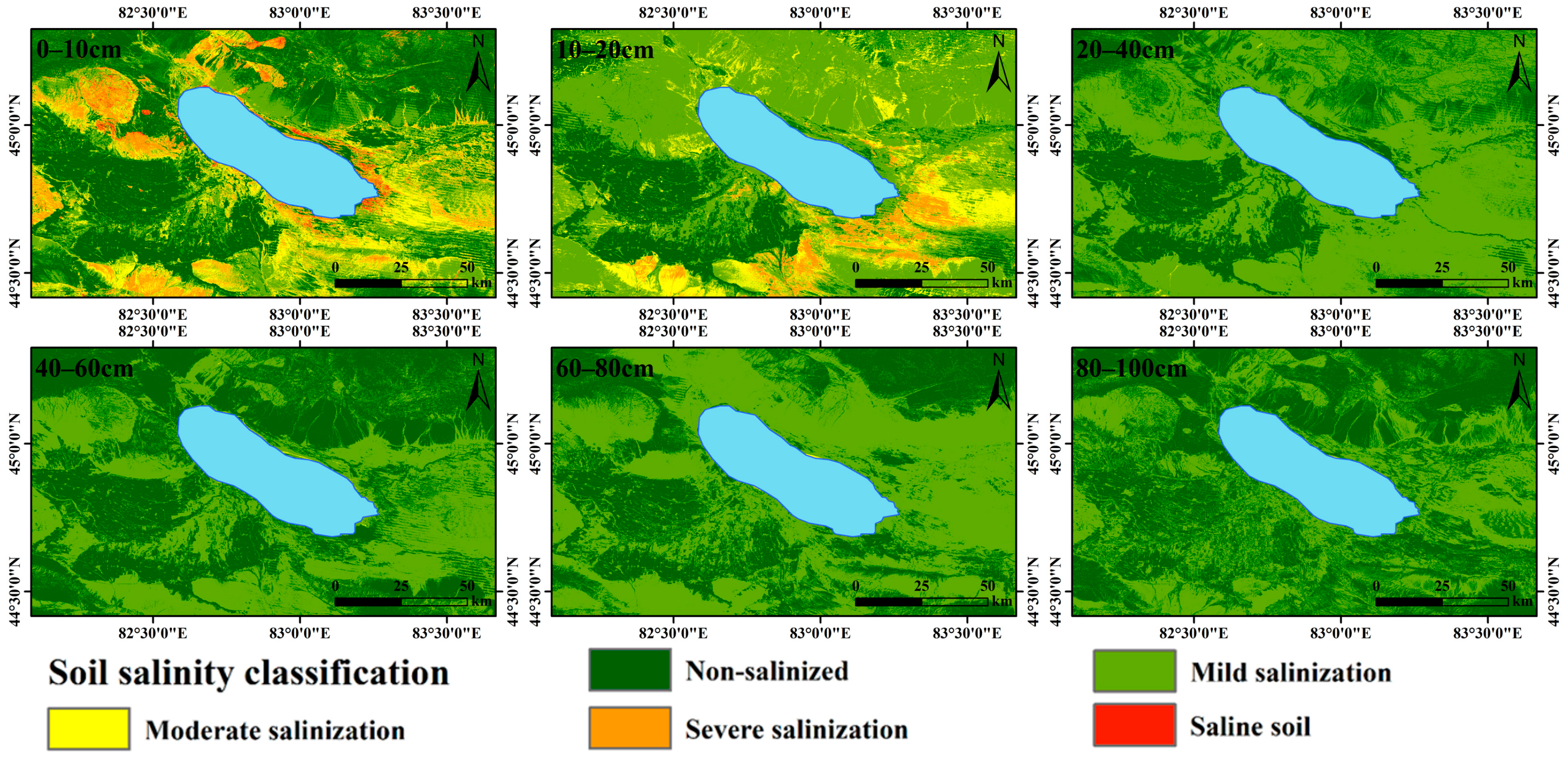

3.4.1. Mapping of Soil Salinity at Multiple Depths in the Ebinur Wetland Reserve

3.4.2. Multi-Year Mapping of Soil Salinity in the Ebinur Wetland Reserve

3.4.3. Trends in Soil Salinity Changes in the Ebinur Wetland Reserve

4. Discussion

4.1. Feature Selection and Model Comparison

4.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Causal Analysis of Salinization in the Ebinur Lake Wetland

4.3. Limitations and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

- The RFLA can effectively extract key features closely associated with soil salinity from high-dimensional spectral data, including vegetation indices, salinity indices, and soil indices. These features, used as inputs for the multi-depth model, not only enhance its predictive capability but also improve the physical interpretability of the inversion results, providing a reference approach for intelligent processing of high-dimensional spectral data.

- The constructed multi-depth CNN model exhibited excellent performance across all soil layers (with test set R2 values generally exceeding 0.5), reaching 0.74 and 0.61 in the 0–10 cm and 40–60 cm layers, significantly outperforming the LSTM and RF models. This indicates that CNN has a notable advantage in capturing spatial features and local nonlinear relationships, making it suitable for high-precision soil salinity inversion and spatial mapping, and providing a reliable technical means for salinization monitoring in arid regions.

- Multi-temporal remote sensing mapping and Sen-MK trend analysis revealed a vertical migration pattern in the study area characterized by declining surface salinity, stable mid-layer salinity, and accumulating deep-layer salinity. The decrease in surface salinity in the oasis area reflects the positive effects of irrigation and land management. In contrast, the significant increase in salinity at depths of 80–100 cm indicates a potential risk of deep-layer salt accumulation. These findings underscore the need for future salinization management to focus on deep-layer salinity and its potential impacts on crop root zones and ecosystem stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional neural net-works |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory networks |

| RF | Random forest |

| RFLA | Random frog leaping algorithm |

Appendix A

References

- Li, J.; Pu, L.; Han, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, R.; Xiang, Y. Soil salinization research in China: Advances and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Ge, X. Study on the inversion and spatiotemporal variation mechanism of soil salinization at multiple depths in typical oases in arid areas: A case study of Wei-Ku Oasis. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 315, 109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinck, J.A.; Metternicht, G. Soil salinity and salinization hazard. In Remote Sensing of Soil Salinizationnization: Impact on Land Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rozema, J.; Flowers, T. Crops for a salinized world. Science 2008, 322, 1478–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R. Plant functional types and their ecological responses to salinization in saline grasslands, Northeastern China. Photosynthetica 2004, 42, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, R.V.; Adamchuk, V.; Sudduth, K.; McKenzie, N.; Lobsey, C. Proximal soil sensing: An effective approach for soil measurements in space and time. Adv. Agron. 2011, 113, 243–291. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, D.; Van Niekerk, A. Machine learning performance for predicting soil salinity using different combinations of geomorphometric covariates. Geoderma 2017, 299, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaan, R.; Taylor, G. Field-derived spectra of salinized soils and vegetation as indicators of irrigation-induced soil salinization. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G.I.; Zinck, J. Remote sensing of soil salinity: Potentials and constraints. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farifteh, J.; Van Der Meer, F.; Carranza, E. Similarity measures for spectral discrimination of salt-affected soils. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 5273–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.R. Visible and near-infrared spectra of minerals and rocks: II carbonates. Mod. Geol. 1971, 2, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.N.; Roush, T.L. Reflectance spectroscopy: Quantitative analysis techniques for remote sensing applications. J. Geophys. Res. Solid. Earth 1984, 89, 6329–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R. Monitoring and the study of the effects of image scale on delineation of salt-affected soils in the Indo-Gangetic plains. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1992, 13, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.; Saxena, R.; Barthwal, A.; Deshmukh, S. Remote sensing technique for mapping salt affected soils. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1994, 15, 1901–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panah, S.; Goossens, R.; De Dapper, M. Study of soil salinity in the Ardakan area, Iran, based upon field observations and remote sensing. In Operational Remote Sensing for Sustainable Development, Proceedings of the 18th EARSeL Symposium on Operational Remote Sensing for Sustainable Development, Enschede,The Netherlands, 11–14 May 1998; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; pp. 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Yang, S.; Wei, Y.; Shi, Q.; Ding, J. Characterizing soil salinity at multiple depth using electromagnetic induction and remote sensing data with random forests: A case study in Tarim River Basin of southern Xinjiang, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Han, J.; Liu, D. Estimating salt content of vegetated soil at different depths with Sentinel-2 data. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ding, J.; Teng, D.; Wang, J.; Huo, T.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; He, B.; Han, L. Updated soil salinity with fine spatial resolution and high accuracy: The synergy of Sentinel-2 MSI, environmental covariates and hybrid machine learning approaches. Catena 2022, 212, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fan, X.; Gao, P.; Guo, L.; Huang, X.; Gao, X.; Pang, J.; Tan, F. Monitoring Soil Salinity in Arid Areas of Northern Xinjiang Using Multi-Source Satellite Data: A Trusted Deep Learning Framework. Land 2025, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihaiti, A.; Nurmemet, I.; Yu, X.; Aili, Y.; Li, S.; Lv, X.; Qin, Y. An enhanced soil salinity estimation method for arid regions using multisource remote sensing data and advanced feature selection. Catena 2025, 256, 109116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, J.; Ge, X. Spatial heterogeneity response of soil salinization inversion cotton field expansion based on deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1437390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Z. Distribution Characteristics and Relationship Between Soil Salinity and Soil Particle Size in Ebinur Lake Wetland, Xinjiang. Land 2025, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, A.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Song, R. The relationship between soil salinity and electrical conductivity across different salinized regions in China. Soil 1997, 29, 54–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S. Soil Agrochemical Analysis; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wulder, M.A.; Roy, D.P.; Radeloff, V.C.; Loveland, T.R.; Anderson, M.C.; Johnson, D.M.; Healey, S.; Zhu, Z.; Scambos, T.A.; Pahlevan, N. Fifty years of Landsat science and impacts. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 280, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z. Soil salinity inversion model of oasis in arid area based on UAV multispectral remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Tong, X.; Zhang, J.; Meng, P.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Yu, P. NIRv and SIF better estimate phenology than NDVI and EVI: Effects of spring and autumn phenology on ecosystem production of planted forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 315, 108819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. The generalized difference vegetation index (GDVI) for dryland characterization. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hall, F.G.; Sellers, P.J.; Marshak, A.L. The interpretation of spectral vegetation indexes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, G. Upscaling remote sensing inversion and dynamic monitoring of soil salinization in the Yellow River Delta, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Guo, B.; Zhang, R. A Novel Approach to Detecting the Salinization of the Yellow River Delta Using a Kernel Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and a Feature Space Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, G.; Chang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, N.; Peng, Z.; Song, Y. Remote Sensing Inversion of Salinization Degree Distribution and Analysis of Its Influencing Factors in an Arid Irrigated District. Land 2024, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silleos, N.G.; Alexandridis, T.K.; Gitas, I.Z.; Perakis, K. Vegetation indices: Advances made in biomass estimation and vegetation monitoring in the last 30 years. Geocarto Int. 2006, 21, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Hong, Y.; Qin, Q.; Liu, L. VSDI: A visible and shortwave infrared drought index for monitoring soil and vegetation moisture based on optical remote sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 4585–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, P.; Flasse, S.; Gregoire, J.-M. Designing a spectral index to estimate vegetation water content from remote sensing data: Part 2. Validation and applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 82, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A.; Guedon, A.; El-Harti, A.; Cherkaoui, F.; El-Ghmari, A. Characterization of slightly and moderately saline and sodic soils in irrigated agricultural land using simulated data of advanced land imaging (EO-1) sensor. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 39, 2795–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douaoui, A.E.K.; Nicolas, H.; Walter, C. Detecting salinity hazards within a semiarid context by means of combining soil and remote-sensing data. Geoderma 2017, 134, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 77, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, C. NDBSI: A normalized difference bare soil index for remote sensing to improve bare soil mapping accuracy in urban and rural areas. Catena 2022, 214, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudiero, E.; Skaggs, T.H.; Corwin, D.L. Regional-scale soil salinity assessment using Landsat ETM+ canopy reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 169, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prout, J.M.; Shepherd, K.D.; McGrath, S.P.; Kirk, G.J.; Haefele, S.M. What is a good level of soil organic matter? An index based on organic carbon to clay ratio. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2021, 72, 2493–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Minasny, B.; Sarmadian, F.; Malone, B. Digital mapping of soil salinity in Ardakan region, central Iran. Geoderma 2014, 213, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of remotely-sensed ecological indexes’ influence on urban thermal environment dynamic using an integrated ecological index: A case study of Xi’an, China. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 3421–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.B.; Yang, Z.; Healey, S.P.; Kennedy, R.E.; Gorelick, N. A LandTrendr multispectral ensemble for forest disturbance detection. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 205, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkheyli, A.; Zain, A.M.; Sharif, S. The role of basic, modified and hybrid shuffled frog leaping algorithm on optimization problems: A review. Soft Comput. 2015, 19, 2011–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Pilon, P. A comparison of the power of the t test, Mann-Kendall and bootstrap tests for trend detection/Une comparaison de la puissance des tests t de Student, de Mann-Kendall et du bootstrap pour la détection de tendance. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2004, 49, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Miao, Q.; Shi, H.; Feng, W.; Hou, C.; Yu, C.; Mu, Y. Spatial Variations and Distribution Patterns of Soil Salinity at the Canal Scale in the Hetao Irrigation District. Water 2023, 15, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Du, X.; Meng, B.; Guo, H. Characteristics and mechanisms of soil salinization in humid climate areas. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Factors influencing usage of subsurface drainage to improve soil desalination and cotton yield in the Tarim Basin oasis in China. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, H.; Tan, M.; Zou, J.; Zong, R.; Dhital, Y.P. The impact of long-term mulched drip irrigation on soil particle composition and salinity in arid northwest China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, N. Variations of soil salinity and cotton growth under six-years mulched drip irrigation. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, Z.M.; Bannari, A.; El-Battay, A.; Hameid, N. Potionential of spectral indices for halophyte vegetation cover detection in arid and salt-affected landscape. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 4632–4635. [Google Scholar]

- Abuelgasim, A.; Ammad, R. Mapping soil salinity in arid and semi-arid regions using Landsat 8 OLI satellite data. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2019, 13, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarbakhsh, A.; Mahmoudabadi, E.; Afzali, S.F.; Khajehzadeh, M. Spatial Prediction of Soil Salinity by Using Remote Sensing and Data Mining Algorithms at Watershed Scale, Northwest Iran. J. Indian. Soc. Remote Sens. 2024, 52, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Zhu, B.; Sun, J. Comparative Study on Different Index Methods in Remote Sensing Monitoring of Drought. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 8289–8291. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, O.H.; Jia, Z. Evaluation of different soil salinity indices using remote sensing techniques in siwa oasis, Egypt. Agronomy 2024, 14, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, J.; Jiang, H.; Xie, K.; Gu, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z. Characteristic Wavelength Optimization Based on Random Frog Algorithm. Acta Opt. Sin. 2021, 41, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-D.; Xu, Q.-S.; Liang, Y.-Z. Random frog: An efficient reversible jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo-like approach for variable selection with applications to gene selection and disease classification. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 740, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Y. Measurement of water content in biodiesel using visible and near infrared spectroscopy combined with Random-Frog algorithm. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2014, 30, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Garajeh, M.K.; Malakyar, F.; Weng, Q.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Lakes, T. An automated deep learning convolutional neural network algorithm applied for soil salinity distribution mapping in Lake Urmia, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Wu, S. A fault diagnosis method for small pressurized water reactors based on long short-term memory networks. Energy 2022, 239, 122298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z. Mapping multi-depth soil salinity using remote sensing-enabled machine learning in the yellow river delta, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulimiti, A.; Wang, Y.-h. Soil organic matter, salinity, and water content in the Aibi Lake Wetland. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2020, 48, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.-R.; Chen, S.-J.; Fan, H.-J.; Chen, M.-Y.; Jia, X.; Huang, T.-C.; Miao, R. Response of soil salinity to change of water area in crisscross between foreshore vegetation and zonal vegetation in Aibi Lake. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 34, 862–871. [Google Scholar]

- Mingliang, Z.; Yanhong, L.; Fadong, L.; China, P. Analysis of the spatial variability of soil moisture and salinity in Ebinur Lake wetlands, Xinjiang. J. Lake Sci. 2016, 28, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuduwaili, J.; Jun-rong, X.; Gui-jin, M.; Man, X.; Gabchenko, M. Effect of soil dust from Ebinur Lake on soil salts and landscape of surrounding regions. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2007, 29, 928–939. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.P.; Grossl, P.R.; Amacher, M.C.; Boettinger, J.L.; Jacobson, A.R.; Lawley, J.R. Selenium and salt mobilization in wetland and arid upland soils of Pariette Draw, Utah (USA). Geoderma 2017, 305, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Bi, W.; He, Y.; Ge, Y.; Mao, X. Optimizing irrigation amount and salinity level for sustainable cotton production and soil health. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 316, 109581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, G.; Song, Z.; Xu, P.; Li, X.; Ma, L. Optimization of Subsurface Drainage Parameters in Saline–Alkali Soils to Improve Salt Leaching Efficiency in Farmland in Southern Xinjiang. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Guo, H.; Zhu, Q.; An, D.; Song, Z.; Ma, L. Optimizing Subsurface Drainage Pipe Layout Parameters in Southern Xinjiang’s Saline–Alkali Soils: Impacts on Soil Salinity Dynamics and Oil Sunflower Growth Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriyev, M.; Mirzahmedov, I.; Boymirzaev, K.; Juraev, Z. Effects of mulching, terracing, and efficient irrigation on soil salinity reduction in Uzbekistan’s Fergana Valley. Cogent Food Agric. 2025, 11, 2449201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Depth | 0–10 cm | 10–20 cm | 20–40 cm | 40–60 cm | 60–80 cm | 80–100 cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Points | 238 | 228 | 226 | 137 | 87 | 83 |

| Environmental Covariates | Formula | References |

|---|---|---|

| Original Band | [26] | |

| NIRv | [27] | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | [26] | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) | [26] | |

| Difference Vegetation Index (DVI) | [26] | |

| Generalized Difference Vegetation Index (GDVI) | [28] | |

| Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI) | [29] | |

| Non-linear Vegetation Index (NLI) | [30] | |

| Ratio Vegetation Index (RVI) | [31] | |

| Optimized Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (OSAVI) | [26] | |

| Kernel Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (KNDVI) | [32] | |

| Enhanced Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (ENDVI) | [33] | |

| Infrared Percentage Vegetation Index (IPVI) | [34] | |

| Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index (ARVI) | [31] | |

| VSDI1 | [35] | |

| VSDI2 | [35] | |

| Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) | [31] | |

| Global Vegetation Moisture Index (GVMI) | [36] | |

| Salinity Index (S1) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (S2) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (S3) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (S5) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (S6) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (S7) | [37] | |

| Salinity Index (S8) | [38] | |

| Salinity Index (S9) | [38] | |

| Salinity Index (SI) | [39] | |

| Salinity Index (SI1) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (SI2) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (SI3) | [26] | |

| Salinity Index (SI4) | [31] | |

| Salinity Index (SIT) | 100 | [26] |

| Salinity Index (SSSI1) | [37] | |

| Salinity Index (SSSI2) | [37] | |

| Normalized Difference Bare Soil Index (NDBSI) | [40] | |

| Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI) | [26] | |

| Canopy Response Salinity Index (CRSI) | [41] | |

| Clay Index (CLEX) | 12 | [42] |

| Gypsum Index (GYEX) | 12 | [43] |

| Carbonate Exponent Index (CAEX) | [43] | |

| Normalized Difference Built-up Index (NDBI) | [44] | |

| Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) | [45] | |

| Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) | [45] | |

| Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI) | [44] | |

| TCB | [46] | |

| TCG | [46] | |

| TCW | [46] |

| Soil Depth | Max (dS/m) | Min (dS/m) | Mean (dS/m) | Standard Deviation | Kurtosis | Skewness | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10 cm | 96.4000 | 0.0032 | 13.3864 | 13.5393 | 6.9544 | 2.1136 | 1.0114 |

| 10–20 cm | 41.4000 | 0.0024 | 7.8128 | 6.7711 | 4.9828 | 1.8862 | 0.8667 |

| 20–40 cm | 25.9000 | 0.0022 | 5.7989 | 4.3117 | 2.6180 | 1.2695 | 0.7435 |

| 40–60 cm | 26.1000 | 0.1254 | 5.3446 | 4.2750 | 4.2378 | 1.7216 | 0.7999 |

| 60–80 cm | 13.8200 | 0.0952 | 4.0591 | 3.1526 | 1.2482 | 1.1850 | 0.7767 |

| 80–100 cm | 12.8800 | 0.0657 | 3.9036 | 2.5971 | 0.6996 | 0.9186 | 0.6653 |

| Soil Depth | Selected Features |

|---|---|

| 0–10 cm | |

| 10–20 cm | |

| 20–40 cm | |

| 40–60 cm | |

| 60–80 cm | |

| 80–100 cm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. Remote Sensing Inversion and Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Multi-Depth Soil Salinity in a Typical Arid Wetland: A Case Study of Ebinur Wetland Reserve, Xinjiang. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3958. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243958

Wang J, Zhang J, Zhang Z. Remote Sensing Inversion and Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Multi-Depth Soil Salinity in a Typical Arid Wetland: A Case Study of Ebinur Wetland Reserve, Xinjiang. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3958. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243958

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jinjie, Jinming Zhang, and Zihan Zhang. 2025. "Remote Sensing Inversion and Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Multi-Depth Soil Salinity in a Typical Arid Wetland: A Case Study of Ebinur Wetland Reserve, Xinjiang" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3958. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243958

APA StyleWang, J., Zhang, J., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Remote Sensing Inversion and Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Multi-Depth Soil Salinity in a Typical Arid Wetland: A Case Study of Ebinur Wetland Reserve, Xinjiang. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3958. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243958