1. Introduction

The escalating issue of marine and underwater debris pollution presents a profound threat to aquatic ecosystems, biodiversity, economic activities, and global water security [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Accurate and efficient monitoring of underwater debris, particularly plastics, is essential for environmental assessment, policy formulation, and the implementation of targeted cleanup initiatives. Traditionally, monitoring methods such as trawling, optical surveys via remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and acoustic mapping have been employed for seabed assessment [

5]. However, these methods are costly, labor-intensive, and spatially constrained, rendering them unsuitable for large-scale, long-term deployment. Furthermore, trawling causes significant habitat disruption [

6], while optical mapping via ROVs faces visibility and mobility limitations in complex underwater terrains [

7,

8,

9]. In light of these limitations, the geoscience and remote sensing communities are increasingly turning to automated, non-intrusive technologies. Unmanned systems and computer vision methods offer promising, cost-effective alternatives for aquatic debris monitoring [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The need for such innovative strategies is underscored by the growing body of legislation emphasizing long-term marine debris surveillance to support effective coastal management [

15,

16].

Deep learning, particularly object detection techniques, has emerged as a cornerstone for automated environmental surveillance [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) family of single-stage detectors is widely acknowledged for its speed-accuracy trade-off [

21,

22,

23,

24], enabling efficient deployment on low-power platforms [

21], including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) [

25,

26] and amphibious underwater imaging systems such as the Aerial-aquatic Speedy Scanner (AASS) [

27,

28]. However, underwater object detection remains challenging because raw underwater images often suffer from severe degradation. Color distortion, low contrast, scattering-induced blur, and illumination-related noise reduce the visibility of key structures [

29], leading detectors to miss objects or generate false positives. Although traditional enhancement techniques have been applied to mitigate these issues [

30], they often fail to recover fine-grained details needed for reliable detection, especially in turbid or complex underwater scenes.

A number of studies have attempted to address these challenges through computer vision-based debris detection and enhanced YOLO architectures. Early methods employed acoustic sensors such as side-scan sonar, which cover wide areas but lack the resolution necessary for discriminating debris types and fail to detect soft materials like plastic bags [

31]. Optical imaging on ROVs improved visual clarity, yet early applications relied heavily on manual annotation, resulting in limited efficiency and accuracy [

32]. With advances in deep learning, CNNs became common for underwater object detection [

33,

34,

35]. Two-stage models like Faster R-CNN provide strong accuracy [

36] but are computationally heavy, while one-stage YOLO detectors [

37,

38,

39,

40] strike a balance between speed and performance. Many versions of YOLO have been modified for underwater tasks by using new backbones, attention modules, or feature fusion [

41]. Among these enhanced YOLO variants, the latest improvement trends lie in feature alignment, multi-scale fusion, and contextual modeling. For instance, CM-YOLO [

42] introduced a context-enhanced multi-scale fusion framework that aligns multi-level features to improve detection in complex scenes. CFFDNet [

43] proposed a complementarity-aware multi-modal fusion design that integrates optical and SAR features to enhance cross-modal feature representation. Similar feature alignment techniques have been applied in other recent detectors, including DMFI-YOLO [

44], RG-YOLO [

45], and EFP-YOLO [

46]. These models demonstrate that aligned and context-aware features improve robustness in object detection scenarios.

While existing enhanced YOLO studies have shown improved performance in some tasks, they still rely on high-quality input images [

47,

48]. Many studies use clear water datasets or basic image enhancement tools like histogram equalization or the Dark Channel Prior [

49]. These tools do not work well in highly degraded conditions. Turbidity, unstable lighting, and occlusion make the image less clear and hide important features [

50]. Perspective changes, messy backgrounds, and deformable waste objects also make detection harder [

51]. This shows the need for effective image restoration methods, which serve as a foundation for reliable underwater object detection.

A growing number of studies have attempted to address image degradation by enhancing images prior to detection. GAN-based methods such as CycleGAN, UGAN, and their variants are commonly used to adjust color and contrast and are often paired with YOLO or Faster R-CNN. For example, [

52] proposed a method that integrates a GAN-based color correction model with an object detection model to analyse the effect of enhancement on underwater object detection. Another work by [

53] shows that enhanced underwater images may still yield poor detection results due to label quality issues. While these methods improve image quality, they may introduce color shifts or texture artifacts that can affect small-object detection. Transformer-based enhancement methods have also been proposed, with advantages in their self-attention mechanisms enabling them to construct a comprehensive global context [

54,

55,

56]. However, these Transformer-based enhancement models usually require large datasets and high computational cost, and still struggle to restore fine structural details lost to scattering and blur. These limitations suggest that current GAN- and Transformer-based enhancement methods do not fully address blurring issues in small-object detection scenarios such as underwater debris detection.

Given these challenges, more flexible generative restoration frameworks have recently gained attention. Diffusion model is a new type of generative method for image enhancement [

57]. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) learn to reverse a noise-adding process and have demonstrated success in super-resolution, inpainting, and color correction [

49,

58,

59]. However, DDPMs rely on Gaussian noise, which does not accurately model underwater distortions. Cold Diffusion is a new version that changes this. It removes the need for random noise and uses fixed distortions like blur as the forward process. The model then learns how to undo these distortions [

60]. This method fits underwater images well because blur and low contrast are common problems in these settings. Until now, few studies have used diffusion models in underwater remote sensing, especially for tasks like object detection [

61]. Most work is still limited to general image tasks. This study applies Cold Diffusion in a detection pipeline. Unlike basic enhancement tools, Cold Diffusion can create lost texture and structure, making the image clearer. The detector then achieves better input and works more accurately [

62]. This method helps solve the long-standing issue of poor image quality in underwater remote sensing.

To fill in the existing gaps in high-quality image enhancement and accurate object detection, this study presents UDD-YOLO, a modified YOLOv12n model for detecting underwater debris. First, it adds a Cold Diffusion model as a pre-processing step. This helps fix many of the image problems mentioned before. Then, it uses an improved detection network. This network has two new parts: (1) The original backbone is replaced with the AMC2f module. This part helps find debris of different sizes by improving multi-scale feature extraction. (2) The loss function is changed to UIoU, which improves the accuracy of bounding boxes, especially for irregular or partly hidden objects. Together, the proposed model is robust yet lightweight, which is suitable for edge-level deployment.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

Application of diffusion models: A Cold Diffusion model is introduced as a pre-processing module as part of a complete underwater detection pipeline. This application is demonstrated to be effective in mitigating severe image degradation and boosting downstream detection accuracy.

An advanced lightweight detector: An advanced lightweight detector based on a tailored YOLOv12n architecture is proposed. The architecture incorporates an AMC2f feature extraction module and a UIoU loss function to collaboratively enhance detection performance for challenging underwater targets while keeping computational cost at a reasonable level. The effectiveness of each innovative component is validated through extensive ablation studies, and the model’s superior performance is demonstrated through comparative experiments against a wide range of mainstream detectors.

In-depth robustness analysis: A series of systematic tests was carried out to assess the model’s resilience to common underwater perturbations, including variations in brightness, Gaussian blur, scattering (haze), and lens distortion. The results confirm its stability and potential for practical field applications.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the data and methods, including the open-source debris dataset, the proposed detection framework, its three key improvements, the training settings, and the evaluation metrics.

Section 3 presents the experimental results, covering the ablation analysis, comparisons with other common algorithms, and comparisons with different image enhancement methods.

Section 4 discusses the experimental findings and provides additional evaluations on model robustness and generalizability.

Section 5 concludes the study and outlines potential directions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

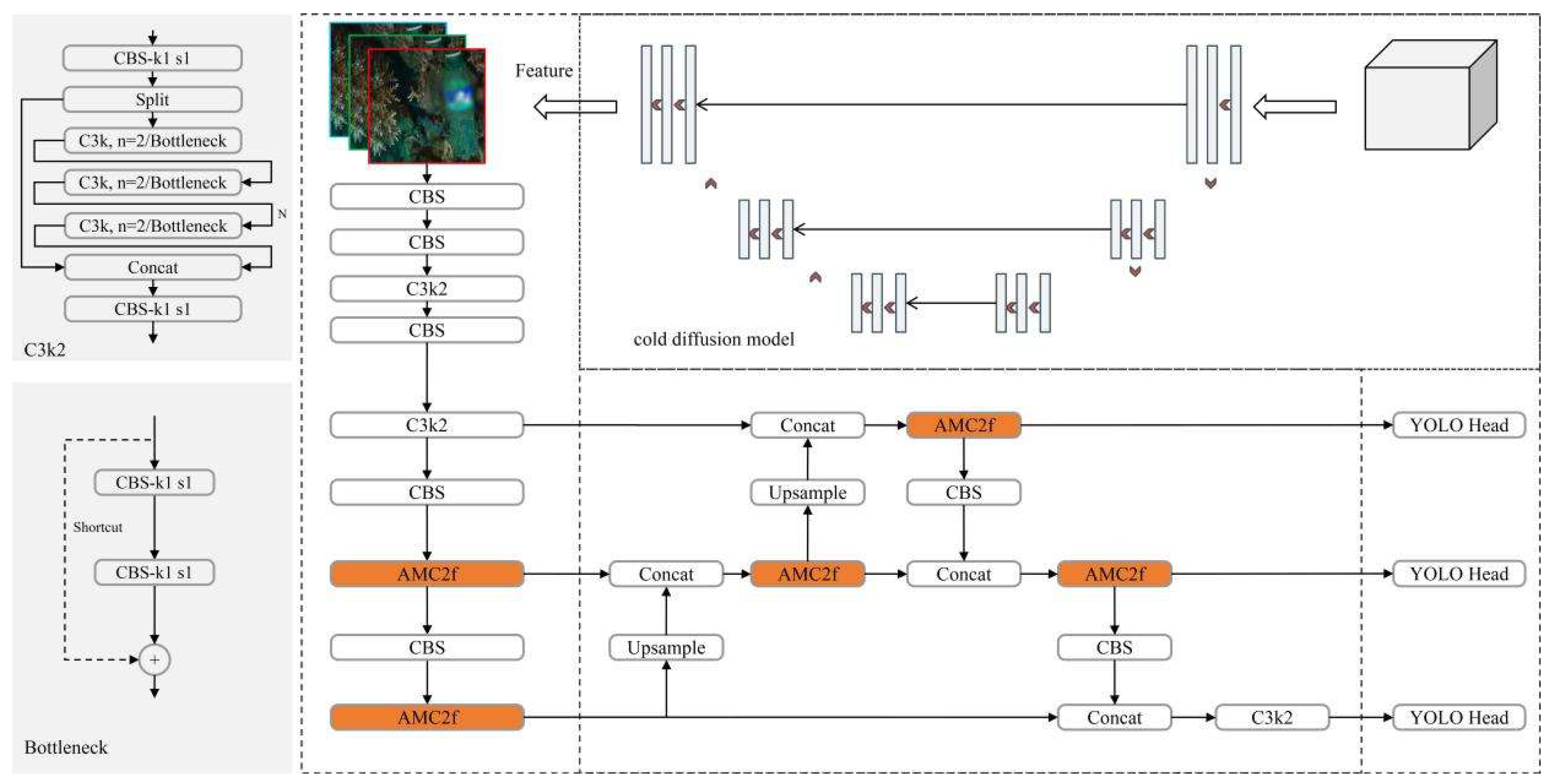

Figure 1 shows the overall framework of this study. A model integrating a Cold Diffusion module, an AMC2f module, and a UIoU loss function was developed. The model was then evaluated against other detectors, including YOLO variants, Faster R-CNN, RT-DETR-L, and MobileNetV2-SSD, as well as under different image enhancement methods. Its robustness was assessed under various degraded visual conditions such as brightness change, Gaussian blur, scattering, and lens distortion. Its transferability was examined through cross-dataset tests to determine whether the model could generalize to new underwater scenes.

2.1. Dataset

In this study, a public dataset for underwater plastic pollution detection [

47] was used. The dataset was made for detecting and monitoring many kinds of plastic and other human-made debris underwater. It has a large set of images that show polluted aquatic environments and capture human waste in different underwater scenes. To deal with the poor quality of underwater images, the Dark Channel Prior (DCP) method was used as a pre-processing step. This improved the image contrast and made it easier to recognize and detect debris.

The dataset contains 15 classes of debris: mask, can, cellphone, electronics, glass bottle (gbottle), glove, metal, misc, net, plastic bag (pbag), plastic bottle (pbottle), general plastic, rod, sunglasses, and tire.

Figure 2 presents examples with bounding boxes that indicate the position and size of objects.

For training, images were set to 640 × 640 pixels. The initial learning rate was 0.01. Optimization used Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with momentum 0.937 and weight decay 0.0005. To enlarge the training set and improve model robustness, Mosaic augmentation was applied [

63]. This method randomly chooses several images, applies flipping and scaling, and then combines them into one image. This created more variation in background and object layouts and helped the model learn better in real underwater scenes with clutter and occlusion.

2.2. Model Architecture

The core of UDD-YOLO is a detection network built on the lightweight YOLOv12n architecture. YOLOv12n is used as the baseline because it has a good balance of speed and performance. It is also suitable for deployment on underwater platforms with limited resources [

64].

Figure 3 shows that our model keeps the main structure of YOLOv12n but adds three changes for underwater debris detection. The changes are (1) an image restoration preprocessor with Cold Diffusion to improve input quality; (2) an AMC2f module to improve multi-scale feature extraction; and (3) a Unified-IoU (UIoU) loss function to make object localization more precise.

2.2.1. Cold Diffusion Model

A fundamental challenge in underwater object detection is the degradation of image quality. As shown in

Figure 2, underwater images often suffer from low contrast, color casts, and, most critically, blurring caused by light scattering and absorption. These issues obscure the essential structural details and textures of debris, significantly impairing the feature extraction capabilities of detection models like YOLOv12n and leading to reduced accuracy. Traditional enhancement techniques, such as filtering or histogram equalization, mainly adjust pixel intensity distributions, which improves contrast or color balance. However, they are unable to reconstruct lost fine structural details or severely blurred edges, resulting in limited improvement for downstream detection. To address this limitation, we introduce an advanced image enhancement preprocessor based on the principles of diffusion models. Our approach is inspired by the powerful generative framework of Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM). On the basis of DDPM, a Cold Diffusion paradigm is adapted, which replaces stochastic Gaussian noise with a deterministic degradation operator that simulates the underwater blur process. By learning to reverse this specific degradation during training, the model recovers sharper edges, clearer object boundaries, and fine textures that are typically lost to scattering and absorption. Because the degradation is deterministic rather than random, this formulation matches the physical characteristics of underwater imaging more closely. In practice, the restored structural information improves the feature extraction capability of YOLOv12n, particularly for small or low-contrast debris objects. Compared with commonly used enhancement methods, Cold Diffusion not only increases perceptual clarity but also generates features that are more aligned with the detector’s feature space, leading to consistent performance gains in our experiments.

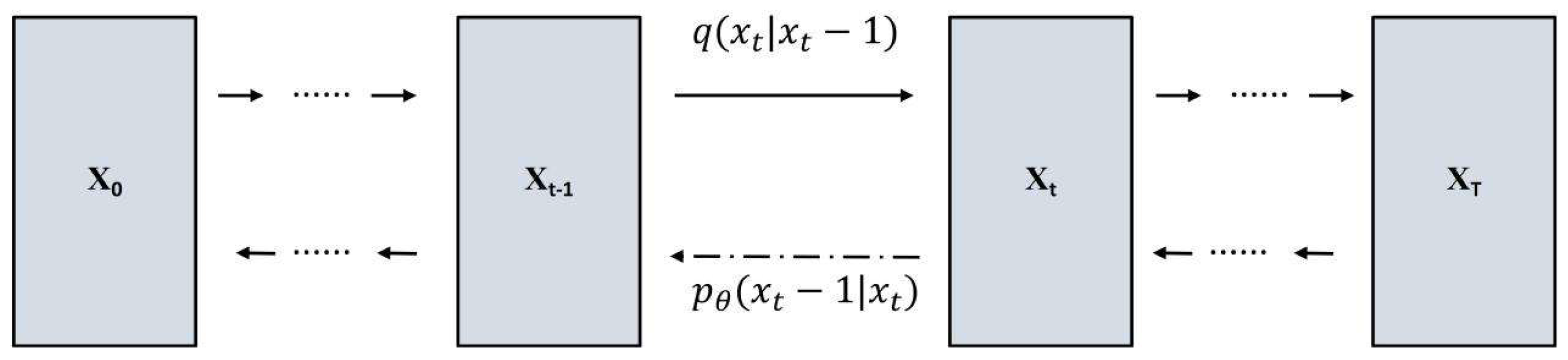

Foundational Theory: Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM)

DDPM is defined as a forward diffusion process

that gradually corrupts the original data

over T time steps [

58]. At each timestep, the data is perturbed with small noise following a predefined variance schedule, ultimately converting the clean input into an approximate Gaussian distribution. In the forward process, a clean image

is gradually perturbed over

steps by adding Gaussian noise according to a predefined variance schedule. A commonly used closed-form expression is

A parameterized reverse process is designed to recover the original data from the degraded input

.

To ensure that the forward process produces data that approximates a standard normal distribution, the noise schedule hyperparameters in the diffusion process are carefully designed. As a result, the prior distribution at the final timestep T is typically set to a standard Gaussian. The reverse process, parameterized by a neural network, is trained to recover the denoising path from the prior distribution back to the original data.

Cold Diffusion Module for Underwater Restoration

However, the Gaussian noise assumption in classical DDPMs does not match the real degradation in underwater imagery. Underwater images are mainly affected by blur, haze, and color shift caused by light scattering, rather than by pixel-wise independent Gaussian noise. Training a model to invert Gaussian noise may therefore fail to fully capture the structured distortions that are most relevant for underwater perception.

To address this mismatch, we adopt the Cold Diffusion paradigm, which replaces stochastic Gaussian noise with deterministic degradation operators that explicitly mimic underwater distortions. Instead of sampling noise, the forward trajectory is defined as

where

denotes a deterministic transform that applies progressively stronger blur and contrast reduction to the clean image

as

increases. The reverse model

is then trained to restore the degraded image toward its clean counterpart step by step. In this formulation, the diffusion mechanism is preserved, but the forward degradation is now physically motivated. Rather than undoing Gaussian noise, the model learns to invert realistic underwater degradations, making the restored images more structurally faithful and visually consistent for downstream detection. The training objective for the Cold Diffusion module is defined as a reconstruction loss:

where

predicts a refined image at timestep

that should approximate the original clean image

.

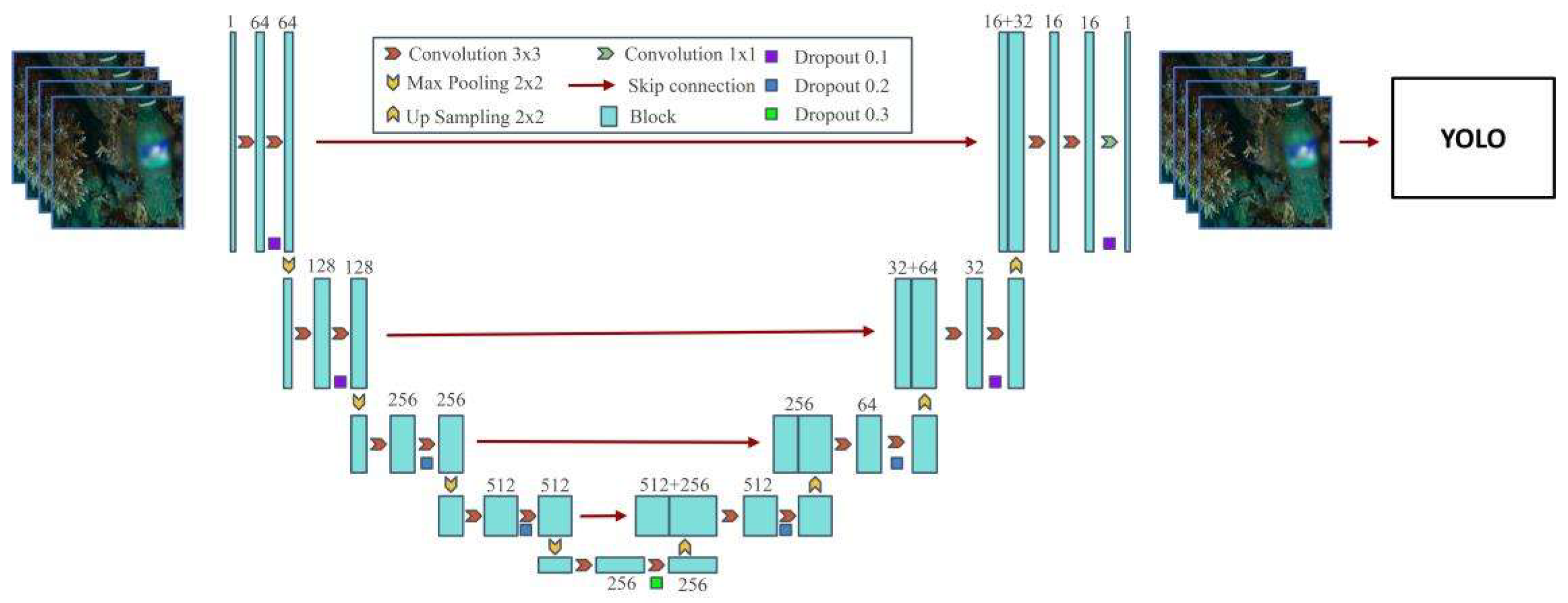

Based on the above formulation, we implement the Cold Diffusion module as a front-end restoration network for UDD-YOLO.

Figure 4 shows the overall design of the network. The network adopts an encoder–decoder architecture with skip connections, similar to U-Net structures commonly used in image restoration. The encoder gradually downsamples the input

to extract hierarchical features capturing both global context (e.g., large-scale haze and illumination gradients) and local structures (e.g., debris edges and textures). The decoder then upsamples and fuses these features, using skip connections to preserve fine details that are critical for small objects such as fishing nets or plastic bags. A lightweight embedding of the timestep

is injected into intermediate layers, enabling the same network to adapt its behavior along different points of the degradation-restoration trajectory.

Furthermore, by combining this pre-processing strategy with YOLOv12n, we effectively decouple the enhancement and detection stages, enabling the detection network to concentrate on identifying key patterns within clean inputs, while the DDPM module specializes in mitigating visual distortions introduced by underwater environments. Empirical evaluations in

Section 3 demonstrate that this joint framework achieves superior detection accuracy compared to baseline methods without pre-processing.

During the training phase of the Cold Diffusion module (illustrated in

Figure 5), a clean underwater image

is first sampled from the data distribution. A timestep

is then randomly drawn, and the corresponding degraded image

is obtained using the timestep-dependent degradation operator

defined. In our implementation,

gradually increases the blur strength and decreases the image contrast as

grows, so that larger timesteps correspond to more severe underwater degradations, consistent with the progressive scattering effects in real scenes.

Instead of injecting Gaussian noise as in classical DDPMs, we construct a degraded image

through a timestep-dependent deterministic operator

:

where

applies a Gaussian blur with a standard deviation

that increases with the timestep

, and

denotes a contrast attenuation operator with a decaying contrast factor

and global mean intensity

. Both

and

are scheduled as simple monotonic functions of the timestep

, where

increases and

decreases with

. Therefore,

gradually increases the blur strength and decreases the image contrast as

grows, so that larger timesteps correspond to more severe underwater degradations, consistent with the progressive scattering and attenuation effects in real underwater scenes. The pair

is then fed into the restoration network

, which is optimized using the Cold Diffusion reconstruction loss

introduced in this section.

This training strategy encourages the model to learn a stable reverse path that incrementally removes blur and restores local contrast, enabling it to recover fine debris details from strongly degraded underwater image inputs.

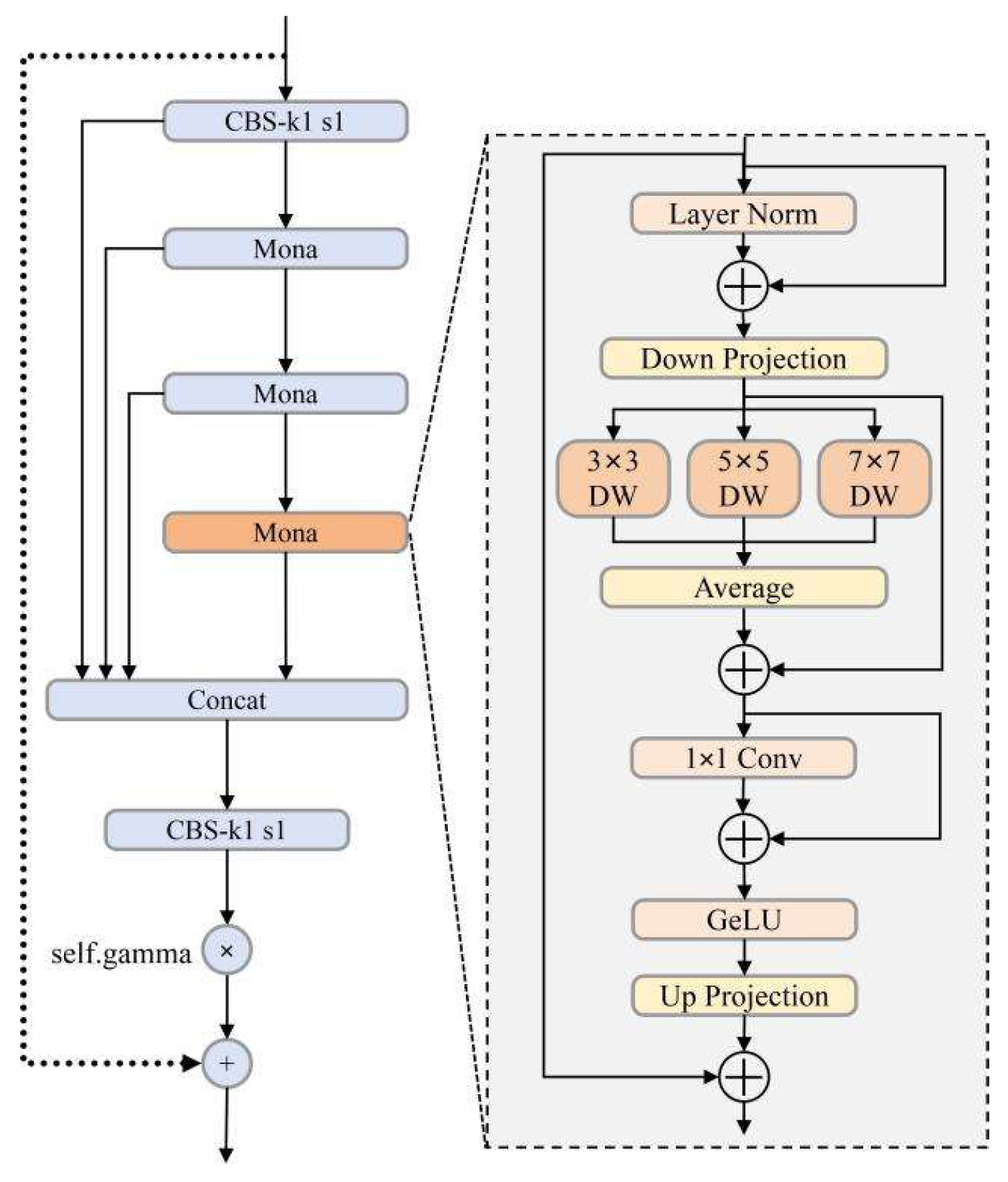

2.2.2. AMC2f Module

Although the YOLOv12n baseline is known for its lightweight and efficient design, its standard feature extraction modules still exhibit limitations in multi-scale object perception. This challenge is especially critical in underwater marine debris monitoring tasks, where objects such as plastic bottles, fishing nets, tires, and face masks differ drastically in size, shape, material, and packaging. Occlusion by algae or sediment and partial embedding in the seabed make feature extraction across scales more difficult. With fixed receptive fields in conventional convolution modules of the YOLOv12n architecture, small objects may lose fine local details, whereas large objects may lose their global structure.

To solve these problems, this study introduces a new module called AMC2f (Adapter-enhanced Multi-cognitive C2f), inspired by the Mona (Multi-cognitive Visual Adapter) mechanism [

65]. The internal architecture of the Mona block is shown on the right side of

Figure 6. Mona begins with Layer Normalization, followed by a Down Projection operation to reduce channel dimensionality. Its core multi-scale perception is enabled by three parallel depth-wise convolution branches with kernel sizes of 3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7, which capture receptive fields at different scales. Their outputs are fused via averaging and further processed by a 1 × 1 convolution, a GeLU activation, and an Up Projection layer, with residual connections ensuring stable gradient propagation. Although Mona provides multi-scale modeling and helps capture semantic information across different receptive fields, its use within underwater scenes still faces challenges. Underwater debris often has blurred boundaries and irregular shapes, and smaller receptive fields may fail to detect vague or low-contrast targets. Similarly, while the original A2C2f module in YOLOv12n has some global modeling ability, it extracts features in a coarse way and cannot capture local details well in underwater scenes.

Because of these limitations, our proposed AMC2f module modifies the feature processing pipeline rather than simply inserting a Mona block into the C2f framework. As shown on the left side of

Figure 6, input features first pass through a conventional convolutional block (CBS) before entering the core of the module, which consists of several sequential Mona blocks. The outputs from these blocks are concatenated with a skip connection from the original input and then processed by another CBS block. This result is scaled by a learnable parameter denoted as self.gamma, which adaptively scales the enhanced feature branch before it is merged with the identity branch. Self.gamma enables content-adaptive refinement according to the degradation level of underwater inputs without increasing inference complexity. Finally, the refined features are added back to the main feature stream through a residual connection. These task-specific modifications are not present in the original Mona design and were introduced to address the edge smoothing, scale variation, and high-frequency noise commonly observed in underwater debris images, making AMC2f a task-adapted extension rather than a simple combination of the Mona block and C2f.

By stacking multiple Mona blocks to benefit from their multi-scale processing capability and incorporating the adaptive self.gamma gating mechanism, AMC2f provides a stronger and more flexible feature modeling capacity than using a single Mona block alone. The residual design supports stable learning even with poor-quality underwater images, while the combination of shallow and deep features enhances robustness against occlusion, shape variations, and background clutter. These characteristics make AMC2f particularly effective for underwater debris detection, where objects exhibit diverse sizes, irregular textures, and can be partly hidden by marine snow, sediments, or algae.

2.2.3. Unified-IoU (UIoU) Loss Function

To solve the common problems in underwater object detection, such as large differences in object scale, frequent occlusion, low visibility, and background clutter, a new bounding box regression loss called Unified Intersection-over-Union (UIoU) is proposed. UIoU is based on normal IoU losses but adds adaptive weighting and geometric consistency constraints. This helps improve object localization and separation in noisy underwater scenes.

Unlike IoU, GIoU, or CIoU, which treat all localization errors the same, UIoU changes the regression gradient based on the predicted IoU score. For high-IoU predictions, the loss tightens the bounding box toward the ground truth. This makes small localization errors more visible and pushes the model to adjust more carefully. For low-quality predictions, the loss softens the penalization by expanding the predicted box and reducing its contribution to the objective function, which helps to stabilize training and prevent gradient explosion in early epochs.

To guide the training process, a cosine annealing schedule is employed to dynamically adjust the scaling ratio. In the early stages of training, the model emphasizes low-quality predictions to accelerate convergence and ensure difficult samples are not neglected. To handle occlusion and overlapping objects, UIoU uses a Focal-inv mechanism. It is similar to Focal Loss but works in the opposite way. It lowers the weight of low-confidence predictions and raises the weight of high-IoU predictions. This makes the model focus on reliable detections and reduce false positives.

UIoU also combines different IoU variants and adds more geometric information, such as IoU score, center distance, aspect ratio, box shape, and orientation. These constraints make bounding box regression stronger and more accurate when detecting debris like nets, tires, and plastic bags. UIoU improves bounding box regression with dynamic scaling. At the start of training, the model makes coarse box adjustments. Later, it makes fine adjustments. A scaling factor called ratio changes from 2.0 to 0.5 during training, which controls the resizing of predicted boxes. This is defined in the following equation:

Here,

w and

h denote the original width and height of the predicted bounding box, and

denotes the scaled box. The basic IoU regression term is

where

can follow advanced IoU variants so that center distance, aspect ratio, shape and orientation constraints are implicitly incorporated. To emphasize high-IoU and high-confidence predictions while reducing the effect of noisy predictions, the Focal-inv weight is defined by combining the IoU score and the classification confidence

:

where α balances the contribution of IoU and confidence. Finally, the Unified-IoU loss is written as follows:

Here, γ is the focusing parameter of the Focal-inv term. This adjustment enhances the model’s focus on hard examples during training. Specifically, the coefficient controls the contribution of the IoU score, while γ governs the influence of the confidence score. UIoU further adds constraints like center point alignment, width-height ratio consistency, and angular similarity. These help the model match object shapes, even for irregular debris under occlusion or complex positions.

The detection framework starts with pre-processing. A Cold Diffusion model restores underwater images and improves clarity and contrast. This reduces the effects of turbidity and poor lighting and gives a better base for feature extraction. In the backbone, the usual YOLOv12n modules are replaced with the AMC2f module. AMC2f improves multi-scale perception and extracts stronger features from both small and large debris. Finally, UIoU is used during training for bounding box regression. Its adaptive weighting and scaling make localization more precise while keeping good generalization.

These three strategies operate synergistically: the Cold Diffusion model improves image quality and supplies high-fidelity input for feature extraction; the AMC2f module extracts high-quality features from enhanced images; and the UIoU loss function optimizes localization based on these features. Together, they transform the lightweight YOLOv12n baseline into an efficient, accurate, and robust underwater object detection system, meticulously tailored for the complexities of underwater environments. The effectiveness of this integrated framework will be thoroughly validated in the subsequent experimental section.

2.3. Network Training and Optimization

Table 1 lists the experimental setup used in this study. The experiments ran on Ubuntu 22.04 with 120 GB memory and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB). The system had a 16-core Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6430 processor. Training and testing were carried out with PyTorch 2.1.0, and GPU support was provided through CUDA 12.1. The Python version was 3.10.

The Cold Diffusion restoration network is first trained independently on the UDD training split using only the reconstruction losses. After convergence, its parameters are frozen, and the network is used as a fixed preprocessing module in front of the detector. During the subsequent training of UDD-YOLO, gradients from the detection loss are not back-propagated into the diffusion module; only the YOLOv12n backbone, neck, head, and the parameters related to UIoU are updated. Both stages use the same underlying training images from the UDD training set. The Cold Diffusion stage adopts simple geometric augmentations, such as random cropping and horizontal flipping, whereas the detector training follows the standard YOLO configuration with Mosaic-based augmentation, scale jittering, and label smoothing. This two-stage strategy allows the diffusion model to specialize in underwater restoration while keeping the detector optimization focused on robust feature learning and localization.

To ensure a fair comparison, all baseline detectors were trained under a unified training protocol, as shown in

Table 2. For all YOLO-family models, the input resolution was fixed to 640

640, and training was performed for 200 epochs with a batch size of 32 and 16 data-loading workers. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) was adopted as the optimizer, with an initial learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.937, and weight decay of 0.0005, following the official YOLO training configuration. Mosaic-based data augmentation, including random flipping and scaling, was applied consistently across all YOLO-based experiments, together with label smoothing to improve generalization. Other representative baselines (Faster R-CNN, MobileNetv2-SSD, RT-DETR-L, and Mamba-YOLO-T) were retrained on the dataset using the same input resolution, number of epochs, and data augmentation policy, while keeping their remaining hyperparameters aligned with their official implementations. No early stopping was used; all models were trained for the full 200 epochs, ensuring comparable training budgets across methods.

In all experiments, each raw underwater image is first passed through a lightweight Dark Channel Prior (DCP)-based dehazing step to suppress strong surface reflections and global water haze. The resulting DCP-corrected image is then fed into the subsequent enhancement module and finally into the YOLOv12n-based detector. In our main configuration, the enhancement module is the proposed Cold Diffusion restoration network, which refines the DCP output and provides structurally clearer inputs for UDD-YOLO.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics for Object Detection

The effectiveness of an object detection model is evaluated using metrics that assess classification accuracy and localization precision [

47]. Precision and Recall are the main indicators of detection quality. Precision is defined as the ratio of true positives (TP) to all predicted positives. It shows how well the model reduces false positives (FPs). Recall is the proportion of true positives relative to the total actual positives. It shows how well the model finds relevant objects [

48]. Localization is assessed using Intersection over Union (IoU), which is the overlap area divided by the union area of the predicted and ground-truth boxes. A higher IoU means better localization [

66].

Precision, Recall, and IoU focus on single predictions or single classes. To check overall performance, Average Precision (AP) and mean Average Precision (mAP) are used. AP refers to the area under the Precision–Recall curve for a single class. mAP is obtained by averaging AP across all classes, providing an overall measure of detection performance.

The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

In this study, mAP@50 is adopted as the primary evaluation metric. This variant assesses mean Average Precision at a fixed IoU threshold of 0.5, striking a balance between strict spatial accuracy and the flexibility required for real-world object variability [

67]. The mAP@50 metric is particularly suitable for underwater environments, where object shapes, scales, and occlusion levels vary substantially. By aggregating AP across categories at this threshold, mAP@50 captures both inter-class generalization and intra-class consistency, offering a robust indicator of model effectiveness in complex scenarios. We also report the mAP@[0.5:0.95], which averages AP over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step of 0.05. Compared with mAP@50, this metric provides a stricter and more fine-grained evaluation of localization quality.

In addition to these accuracy-oriented indicators, we also report the computational complexity and runtime efficiency of each detector. Specifically, we use FLOPs, expressed in units of GFLOPs (denoted as FLOPs(G)), to quantify the number of floating-point operations required for a single forward pass at an input resolution of 640 × 640. Furthermore, FPS (frames per second) is adopted to measure the actual inference with a batch size of 1. Note that FLOPs(G) and FPS are computed only for the detector backbone, neck, and head, excluding the DCP and Cold Diffusion enhancement modules.

Collectively, these metrics provide a rigorous framework for evaluating object detection models. While Precision, Recall, and IoU assess specific aspects of detection quality, AP and mAP offer broader insights across categories. GFLOPs and FPS characterize how suitable each model is for real-time deployment on resource-constrained underwater platforms. Together, they facilitate a nuanced and balanced evaluation of a model’s strengths, weaknesses, and real-world applicability in underwater debris detection.

3. Results

3.1. Ablation Experiments

To quantitatively assess both the separate and combined effects of the proposed components, ablation experiments were carried out on three main parts: (①) the UIoU loss function, (②) the AMC2f feature extraction module, and (③) the Cold Diffusion-based image enhancement mechanism. The experimental results and corresponding performance metrics are summarized in

Table 3.

This baseline performance reflects the efficiency-oriented design of YOLOv12n, which prioritizes fast inference and compact size over complex contextual reasoning. Its high precision (80.8%) stems from its conservative bounding box regression, which favors confident, well-localized detections. However, the lower recall (68.0%) suggests a tendency to miss ambiguous or partially occluded debris, especially in underwater scenes with turbidity or overlapping objects. This trade-off is characteristic of lightweight detectors lacking deeper multi-scale or semantic modeling mechanisms, which are crucial for recovering difficult targets in visually degraded environments. The parameter count of 2.56 M remains relatively low, but this configuration does not yet benefit from targeted optimization modules (e.g., UIoU or AMC2f) that improve generalization under uncertainty or visual degradation. Despite its efficiency, this configuration exhibited limited robustness in handling visual noise, scale variation, and boundary ambiguity, which are challenges commonly encountered in underwater debris detection.

As shown in

Table 3, each proposed module contributes incrementally to performance improvement, and the full model achieves the highest mAP@50. The three components are the UIoU loss function, the AMC2f feature extractor, and the Cold Diffusion pre-processing procedure. In the YOLOv12n-1 configuration, the standard IoU-based loss was replaced with the proposed UIoU loss function. This modification resulted in a slight reduction in precision to 78.8%, while recall improved to 71.4% and mAP@50 increased to 77.9%. The number of parameters and the model size of YOLOv12n-1 remain unchanged compared with the YOLOv12 baseline.

Building upon this, the YOLOv12n-2 variant incorporated UIoU together with the AMC2f module. This configuration achieved notable gains across all key metrics, with precision reaching 82.4%, recall increasing to 77.3%, and mAP@50 improving to 81.0%. Compared with YOLOv12n-1, YOLOv12n-2 added only 3616 parameters, and the overall model size remains 5.5 MB, preserving its lightweight design.

The complete integration of all proposed components further improved overall performance. With the inclusion of Cold Diffusion pre-processing, the model achieved the best results, reaching 87.3% precision, 75.1% recall, and 81.8% mAP@50. This configuration retains the same number of parameters and the same model size as YOLOv12n-2.

Figure 7 illustrates the qualitative impact of the proposed components using representative examples of underwater debris. By comparing the confidence scores and bounding boxes across each row, it can be observed that the baseline YOLOv12n model shows limited confidence (average scores of 0.33, 0.64, and 0.72) and incomplete object localization (bounding boxes not fully aligned with the object). After introducing the UIoU loss in the YOLOv12n-1 configuration, the bounding boxes become more stable, and the confidence scores increase moderately, indicating improved localization precision. With the addition of the AMC2f module in the YOLOv12n-2 configuration, feature representation is further strengthened, yielding higher confidence and more complete object boundaries even under low contrast or partial occlusion. The full model with Cold Diffusion pre-processing achieves the highest confidence scores and the most accurate detections across all examples.

In summary, the ablation study validates the individual and combined effectiveness of the proposed components. The UIoU loss enhances localization precision through quality-aware regression; the AMC2f module improves multi-scale feature representation; and the Cold Diffusion mechanism mitigates visual degradation in underwater imagery. Together, these components form an effective framework designed to address the specific challenges of underwater debris detection, achieving high accuracy without sacrificing computational efficiency.

3.2. Comparison with Different Detectors

To assess the performance of UDD-YOLO, it was compared against several widely used detectors. These involved two-stage models like Faster R-CNN, transformer-based detectors like RT-DETR, SSD networks, and lightweight YOLO variants. All models used the same dataset, image resolution, and training setup to ensure fairness in comparison.

Table 4 reports the results, covering precision, recall, mAP@50, parameter count, model size, FPS and FLOPs. In addition, all metrics are measured for the detector (backbone + neck + head) only, with an input size of 640 × 640 and batch size = 1 on a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU; the DCP and Cold Diffusion preprocessing modules are not included in these complexity metrics.

Among the two-stage models, Faster R-CNN achieved a respectable precision of 75.6%, recall of 73.0%, and mAP@50 of 75.5%, but suffered from high computational complexity, with over 28 million parameters and a model size of 108.7 MB. Despite its accurate region proposal mechanism, the large model size and slower inference make it less suitable for real-time deployment in resource-constrained underwater environments.

Lightweight one-stage detectors like MobileNetv2-SSD and YOLOv3-tiny offer fast inference and compact size, but they deliver relatively lower detection performance, with mAP@50 of 54.3% and 65.5%. These shortcomings arise from limited representational ability and weaker robustness when detecting small or partly occluded underwater debris.

Recent YOLO family models, including YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv11n, achieved balanced results in accuracy and efficiency. Among them, YOLOv8n reached a peak mAP@50 of 78.2% and precision of 86.2%, highlighting the advantage of its updated head and neck design. YOLOv12n, the direct baseline for our study, reported mAP@50 of 76.8%, but had limited recall (68.0%) due to weaker adaptability to image degradation and inconsistency in underwater scenes.

As presented in

Table 4, the proposed UDD-YOLO surpasses multiple advanced baseline detectors with higher mAP@50, demonstrating strong detection ability under real underwater conditions. The proposed model demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving a precision of 87.3%, recall of 75.1%, and mAP@50 of 81.8%, while maintaining the same parameter size (2.56 M) and model footprint (5.5 MB) as YOLOv12n. This improvement validates the effectiveness of the three integrated components: the Cold Diffusion pre-processing helps correct brightness variations and recover structural details lost due to blur or scattering, enhancing the overall image quality prior to detection. Meanwhile, the adaptive self.gamma mechanism in AMC2f improves the model’s responsiveness to different lighting conditions. Additionally, AMC2f’s multi-branch structure enables robust feature extraction across varying levels of blur. When local details are obscured, the larger 5 × 5 and 7 × 7 kernels can still capture global patterns and object contours, compensating for the limited effectiveness of smaller kernels like 3 × 3.

As representative recent architectures, RT-DETR-L and Mamba-YOLO-T provide strong baselines in this comparison. RT-DETR-L leverages a transformer encoder–decoder with global self-attention and query-based decoding, which is well-suited for complex object interactions. However, on our dataset, it achieves only 75.1% mAP@50 with 25.7 M parameters, whereas UDD-YOLO attains 81.8% mAP@50 with only 2.56 M parameters. This indicates that a carefully tailored lightweight architecture with diffusion-based pre-processing can surpass a heavy transformer detector in both accuracy and real-time efficiency for underwater debris detection. Similarly, Mamba-YOLO-T exploits Mamba-based state space modeling and obtains 76.5% mAP@50 with 5.99 M parameters but still lags behind UDD-YOLO in precision, recall, and overall mAP@50. These comparisons highlight that, despite the advanced global modeling capabilities of transformer- and Mamba-based detectors, the proposed UDD-YOLO achieves a more favorable accuracy-efficiency trade-off by explicitly addressing underwater degradation.

In addition, our model achieves a favorable trade-off between detection accuracy and computational cost. Although integrating the enhanced modules slightly increases the FLOPs(G) (0.5 G) compared with the original YOLOv12n baseline, the overall complexity still remains in the lightweight regime and is clearly lower than that of the larger detectors considered in the comparison. At the same time, UDD-YOLO maintains real-time inference with competitive FPS, indicating that the performance gain mainly comes from more effective feature representation.

Figure 8 compares the detection outputs of various detectors, showing that several baselines either miss the target or produce less accurate bounding boxes under degraded underwater conditions. In contrast, the proposed UDD-YOLO generates clearer and more precisely localized detections with a higher confidence score, demonstrating its advantage in handling blur, low contrast, and complex backgrounds.

In conclusion, the proposed method outperforms all comparison models across key detection metrics while maintaining a lightweight and deployable architecture. These results affirm the practicality and scalability of our approach for real-time underwater garbage detection tasks, particularly in environments with complex visual noise, occlusions, and diverse object geometries.

3.3. Comparison with Different Image Enhancement Methods

To further clarify the effect of the proposed Cold Diffusion enhancement on detection performance, we conducted a comparison experiment by pairing a fixed YOLOv12n-2 in

Section 3.1 with different underwater enhancement strategies. In this experiment, the detector weights are kept unchanged, and only the input pre-processing is modified at inference time. Specifically, we evaluate six configurations on the test set: (1) YOLOv12n-2 with raw underwater images, (2) YOLOv12n-2 with global histogram equalization (HE), (3) YOLOv12n-2 with Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE), (4) YOLOv12n-2 with Dark Channel Prior (DCP)-based dehazing, (5) YOLOv12n-2 with a representative GAN-based enhancement method [

64], and (6) YOLOv12n-2 with the proposed Cold Diffusion enhancement (UDD-YOLO).

For all configurations in this subsection, the input to each enhancement module (HE, CLAHE, DCP-only, StyleGAN3, and Cold Diffusion) is the same DCP-corrected image, and the enhanced result is then fed to the same YOLOv12n-2 detector. The detection metrics, including precision, recall, mAP@50, and mAP@[0.5:0.95], are reported in

Table 5.

YOLOv12n-2 uses the raw underwater images as input and therefore reflects the intrinsic robustness of the baseline detector. As shown in

Table 5, this configuration achieves 80.9% precision, 75.3% recall, 80.1% mAP@50, and 60.1% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. Histogram Equalization (HE) is a global contrast enhancement technique that redistributes the intensity of the histogram to approximate a uniform distribution, thereby stretching frequently occurring gray levels over a wider range. When applied before detection, YOLOv12n-2 + HE yields 81.1% precision, 74.1% recall, 80.3% mAP@50, and 58.3% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. Compared with the raw baseline, mAP@50 remains similar, but recall and mAP@[0.5:0.95] decrease, indicating that HE tends to amplify background noise and haze. As a result, the detector misses more objects, especially small or distant debris.

Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) performs histogram equalization in small tiles and clips the histogram to avoid over-amplifying noise, aiming to enhance local contrast under non-uniform illumination. With CLAHE, YOLOv12n-2 attains 83.6% precision, 74.6% recall, 80.8% mAP@50, and 61.2% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. The higher precision and slightly improved mAP@50 and mAP@[0.5:0.95] compared with the raw baseline suggest that some low-visibility debris becomes more salient and better localized. However, there is a reduction in recall compared to the YOLOv12n-2 (RAW).

Dark Channel Prior (DCP)-based enhancement estimates a transmission map and ambient light under the assumption that at least one color channel is very dark in haze-free patches, thereby removing veiling light and sharpening edges. When combined with YOLOv12n-2, DCP improves precision to 82.4% and slightly increases mAP@50 to 81.0%, while recall increases to 76.3%. This modest mAP gain indicates that suppressing underwater haze and enhancing boundaries can help the detector localize clearer debris.

StyleGAN3-based underwater enhancement uses a generator-discriminator framework to learn a mapping from raw to visually improved images, focusing on correcting color casts and improving perceptual quality. In

Table 5, YOLOv12n-2 + StyleGAN3 reaches 86.5% precision, 75.6% recall, 81.5% mAP@50, and 62.1% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. The notably higher precision suggests that GAN-based enhancement makes debris visually more salient and increases the detector’s confidence. However, the recall remains lower than the baseline. Consequently, the overall gain over raw images is modest, and the enhancement is not uniformly beneficial across all debris types.

UDD-YOLO integrates a Cold Diffusion-based restoration module that performs deterministic blur-and-contrast modeling tailored to underwater degradation. With this complete design, UDD-YOLO achieves 87.3% precision, 75.1% recall, 81.8% mAP@50, and 62.3% mAP@[0.5:0.95], which is the best overall precision–recall trade-off. Compared with the YOLOv12n-2 (Raw) baseline, UDD-YOLO improves precision by 6.4 points, mAP@50 by 1.7 points, and mAP@[0.5:0.95] by 2.2 points, while maintaining a comparable recall level.

3.4. Effect of Different IoU-Based Regression Losses

To evaluate the effect of different IoU-based regression losses under a fair setting, we conduct a controlled experiment where only the bounding-box regression loss is changed while keeping the other architectures and training protocol identical. Specifically, we adopt the UDD-YOLO as the base model and compare five loss variants: the default CIoU loss [

68], GIoU [

69], SIoU [

70], and the adopted UIoU (UDD-YOLO). All models are trained on the dataset with the same input resolution (640

640), number of epochs, optimizer, and data augmentation strategy as described in

Section 2.3. The comparison results, including precision, recall, mAP@50, and mAP@[0.5:0.95], are summarized in

Table 6.

CIoU explicitly incorporates the overlap area, center distance, and aspect ratio into a unified loss and is widely used in recent YOLO variants. When the original loss is replaced by CIoU, UDD-YOLO attains 84.9% precision, 75.0% recall, 81.1% mAP@50, and 60.9% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. Compared with the original loss, this corresponds to gains of +1.1 points in precision, +1.0 points in recall, +0.3 points in mAP@50, and +0.5 points in mAP@[0.5:0.95].

GIoU extends the standard IoU by penalizing the area of the smallest enclosing box, aiming to accelerate convergence when the predicted and ground-truth boxes do not overlap. With GIoU, UDD-YOLO achieves 84.1% precision, 74.7% recall, 81.3% mAP@50, and 60.3% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. Although mAP@50 is slightly higher than that of CIoU, the recall and mAP@[0.5:0.95] are lower than those of both CIoU and the original loss.

Under SIoU, UDD-YOLO obtains 85.6% precision, 74.4% recall, 80.7% mAP@50, and 61.8% mAP@[0.5:0.95]. Compared with the original loss, SIoU markedly improves precision and increases mAP@[0.5:0.95] by 1.4 points, but slightly reduces recall and mAP@50. This pattern suggests that SIoU favors high-quality, well-aligned boxes and improves performance at stricter IoU thresholds, yet may sacrifice some detections of ambiguous or low-contrast debris, leading to a modest drop in overall detection rate.

The proposed UIoU integrates cosine-annealed scaling and Focal-inv weighting into an IoU-style loss, dynamically emphasizing high-IoU, high-confidence predictions while suppressing noisy low-IoU samples. With UIoU, UDD-YOLO achieves 87.3% precision, 75.1% recall, 81.8% mAP@50, and 62.3% mAP@[0.5:0.95], which are the best overall results among all tested losses. Relative to the original loss, UIoU improves precision by 3.5 points, recall by 1.1 points, mAP@50 by 1.0 points, and mAP@[0.5:0.95] by 1.9 points. Compared with CIoU, UIoU still gains 2.4 points in precision and 1.4 points in mAP@[0.5:0.95]. These improvements confirm that quality-aware reweighting and dynamic scaling are particularly effective for underwater debris, where many objects are small or partially occluded and accurate boundary regression is crucial.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Modifications Contributing to Performance Improvement

The ablation study, detectors comparison, image enhancement methods comparison, and loss function comparison presented in

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4 provide insight into why the proposed components contribute to improved detection performance under complex underwater conditions.

For the loss function, UIoU enhances localization robustness by dynamically reweighting predictions according to their estimated quality. Compared with CIoU, GIoU, and SIoU, UIoU provides a more stable optimization signal under irregular object shapes and partial occlusion. CIoU benefits from explicit geometric constraints, but its improvements under strict IoU thresholds remain limited in cluttered underwater scenes. GIoU adjusts boxes more aggressively when predictions and targets do not overlap, yet its advantage does not fully translate to high-IoU localization in underwater debris detection, where targets are small and frequently embedded in complex backgrounds. SIoU improves orientation and aspect-ratio consistency, but its gains remain moderate compared with the quality-aware formulation of UIoU. These comparisons collectively highlight why UIoU is better aligned with underwater debris detection, where bounding boxes often feature irregular shapes and uncertain boundaries.

The AMC2f module strengthens multi-scale feature representation by capturing both fine textures and larger structural cues. This enables the detector to maintain confident predictions even in low-contrast scenes or under partial occlusion, explaining the consistent improvements observed across the ablation results. Its adaptive multi-branch structure ensures that both coarse and fine features are preserved, providing stable representations for downstream localization and classification.

The Cold Diffusion enhancement mechanism contributes substantially to the final performance. By restoring edge sharpness and local contrast, it provides clearer visual cues that improve feature extraction and facilitate more complete object delineation. Unlike general enhancement tools such as HE, CLAHE, DCP, or GAN-based enhancement, Cold Diffusion avoids brightness inconsistency, halo artifacts, and generated textures. Instead, it performs task-oriented structural restoration, resulting in more consistent recall and higher precision across diverse underwater conditions.

Together, these three components form a complementary framework: Cold Diffusion improves the input domain, AMC2f extracts robust multi-scale features, and UIoU refines localization with high stability. Their combined effects explain the substantial improvements reported in

Section 3 and demonstrate the suitability of the proposed design for underwater debris detection.

4.2. Robustness Against Degraded Input Data

In real-world underwater environments, image quality is frequently degraded due to various factors such as illumination variation, suspended particles, optical distortion, and lens fogging. To evaluate the robustness of the proposed detection model under such adverse conditions, a series of controlled degradation tests was performed on the marine debris dataset. The performance under these conditions is visualized in

Figure 9, with subplots (a–d) corresponding to brightness, blur, scattering, and distortion perturbations, respectively.

4.2.1. Brightness Perturbation

To assess the model’s robustness under varying illumination conditions, brightness perturbations were applied by converting RGB images into the LAB color space and systematically modifying the L-channel, which encodes luminance information. By applying offset values of ΔL = {−30, −20, −10, 0, +10, +20, +30}, a wide spectrum of underwater lighting scenarios was simulated, ranging from extremely dark to overly bright environments.

As depicted in

Figure 9a, all models exhibited performance degradation at extreme luminance levels, primarily due to reduced contrast and loss of edge definition. However, the proposed UDD-YOLO model consistently achieved the highest mAP@50 across all brightness conditions, indicating superior adaptability to illumination inconsistencies. This resilience may be attributed to two key design elements: (1) the Cold Diffusion pre-processing module, which enhances local contrast and restores details lost due to underexposure or overexposure, and (2) the adaptive γ-gating mechanism within the AMC2f module, which dynamically adjusts the model’s feature response based on varying input intensities. Such adaptability is essential for real-world deployment, especially in underwater missions where natural light fluctuates with depth, turbidity, and artificial light interference [

71].

4.2.2. Gaussian Blur Perturbation

Gaussian blur with standard deviations σ = {0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5} was applied to emulate vision degradation resulting from underwater housing fogging or particulate matter in turbid water columns. This operation acts as a low-pass filter, diminishing sharp transitions and thereby degrading edge definition, as described mathematically below:

As illustrated in

Figure 9b, while detection accuracy of all models declined with increased blur intensity, the proposed model retained superior performance. This suggests that the model’s architecture effectively captures global semantic information, which is less sensitive to local texture degradation [

72].

4.2.3. Scattering and Haze Simulation

Underwater visibility is often compromised by the presence of suspended particles and dissolved organic matter, which cause forward scattering and haze effects. To simulate this phenomenon, scattering noise was applied using a synthetic scattering function, with coefficients β = {0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5}, thereby degrading image clarity in a controlled manner.

As shown in

Figure 9c, detection accuracy declined across all models with increasing haze levels due to contrast attenuation and edge softening. The proposed model maintained a notably higher detection performance, outperforming other baselines under all tested conditions. This can be largely credited to the Cold Diffusion module, which acts as an effective pre-enhancement filter by recovering degraded structural and textural information from the noisy inputs. Additionally, the multi-scale convolution branches within AMC2f help preserve coarse-to-fine object representations even in low-visibility situations, reinforcing detection accuracy in hazy scenes such as estuarine zones, harbor waters, or offshore environments impacted by sediment plumes [

68].

4.2.4. Lens Distortion

Wide-angle and fisheye lenses commonly used in underwater photography introduce nonlinear spatial distortion, leading to geometric warping effects that challenge conventional object detection networks. To replicate such conditions, increasing levels of radial distortion were simulated using coefficients k = {0.0001, 0.0002, 0.0005, 0.0010, 0.0020}, mimicking real-world optical aberrations caused by underwater dome ports or wide-angle housings.

In

Figure 9d, it is evident that most baseline detectors suffered from substantial drops in accuracy as distortion increased, with object boundaries being stretched or compressed. UDD-YOLO, however, exhibited consistent performance, showcasing its ability to tolerate moderate-to-severe geometric distortion. This robustness stems from the spatial feature alignment mechanism implicitly introduced through the AMC2f’s multi-scale structure and the residual feature aggregation in Mona blocks, which together allow the network to recalibrate feature maps and mitigate spatial inconsistencies. This property enhances its applicability in practical marine surveys where diverse optics and camera configurations are unavoidable.

4.3. Generalizability and Transferability

The proposed model demonstrates superior robustness under multiple types of image degradation. This capability enhances its applicability to real-world underwater garbage detection tasks, where environmental variables and imaging imperfections are unavoidable. The integration of Cold Diffusion pre-processing, the AMC2f module, and the Unified-IoU loss is likely responsible for this enhanced robustness across diverse visual challenges.

To further evaluate the generalizability and transferability of the proposed UDD-YOLO model in diverse underwater environments, we conducted additional experiments on two independent underwater litter datasets collected from different geographic and hydrological conditions: the Riverbed Litter Dataset from the Hongqi River in Yunnan, China [

26], and the Seafloor Debris Dataset from Koh Tao, Thailand [

5]. Remarkably, UDD-YOLO achieved a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.83 on the riverbed dataset, surpassing the best-performing model, RBL-YOLO (mAP = 0.80), proposed in the original study. Similarly, on the Koh Tao seafloor dataset, UDD-YOLO reached an mAP of 0.94, outperforming the previously reported optimal model SFD-YOLO (mAP = 0.91). These results demonstrate the strong transferability and robustness of UDD-YOLO across datasets with distinct underwater conditions, including variations in water turbidity, object morphology, and background complexity.

Notably, both RBL-YOLO and SFD-YOLO were developed by modifying the YOLOv8s architecture, which is significantly larger in model size compared to UDD-YOLO. In contrast, our proposed model maintains comparable or superior detection performance with only approximately one-fourth the model size, highlighting its potential for deployment on resource-constrained platforms such as Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), remotely operated systems, or handheld detection devices. This compact yet powerful architecture underscores the practical advantages of UDD-YOLO in real-world underwater ecological monitoring scenarios, particularly where computational and storage resources are limited.

5. Conclusions

This study presents UDD-YOLO, a novel underwater object detection framework that leverages diffusion-driven image enhancement to address the persistent challenges of poor visibility, occlusion, and morphological diversity in underwater environments. By integrating a Cold Diffusion pre-processing module, an AMC2f feature extraction backbone, and a UIoU loss function, the proposed method significantly enhances both visual quality and detection robustness in complex marine scenes.

Comprehensive tests on a public underwater plastic pollution dataset show that the proposed model outperforms other methods over eleven advanced detection frameworks, such as Faster R-CNN, RT-DETR-L, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv12n. The model reached mAP@50 of 81.8%, with 87.3% precision and 75.1% recall, while maintaining a compact design of only 2.56 M parameters and 5.5 MB in size. These results validate the effectiveness of each integrated module: the Cold Diffusion module restores structural and textural fidelity without introducing stochastic noise, the AMC2f module enables multi-scale and morphology-aware representation, and the UIoU loss strengthens localization performance under occlusion and boundary ambiguity.

The proposed architecture not only achieves high detection accuracy while keeping computational efficiency, which makes it suitable for real-time use on edge devices like underwater drones or autonomous robots. Furthermore, the diffusion-based enhancement strategy marks a paradigm shift in underwater computer vision by introducing generative restoration as a pre-detection process.

Future research will focus on expanding this framework to multi-object tracking and instance segmentation tasks in real underwater environments, as well as integrating adaptive diffusion models that can dynamically respond to scene-specific degradation levels. The promising results of this study lay the foundation for intelligent and scalable systems for marine monitoring, contributing to the long-term goal of environmental preservation and sustainable ocean resource management.