DEM-Based UAV Geolocation of Thermal Hotspots on Complex Terrain

Highlights

- A novel DEM-based algorithm is proposed for geolocating thermal hotspots detected by UAVs over both flat and mountainous terrain.

- The method reformulates the Bresenham traversal algorithm into a direction-vector–based approach and introduces a lightweight, cell-level estimation of the optical ray altitude.

- The algorithm enables real-time or post-processed hotspot geolocation with mean positional errors below 4.2 m, even in complex topography.

- Operationally deployed by the Corsican fire services since 2024, the method has already proven effective for field intervention and hotspot monitoring, providing highly valuable operational support.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Basic Coordinate Frames and Transformations

2.2. Hotspot Geolocation Algorithm

2.2.1. Step 1—Thermal Image Acquisition

2.2.2. Step 2—Optical Sensor Pose Recording

2.2.3. Step 3—Hotspot Detection and Pixel-Level Extraction

2.2.4. Step 4—Per-Hotspot Processing

- Step 4.1—Computation of the direction vector in the camera frame

- Step 4.2—Projection of the optical center and Direction Vector in the DEM Plane (in the ENU frame)

- Step 4.3—DEM Traversal Along the Projected Direction

- A unit increment is performed along the axis;

- The variable is evaluated:

- If , the same row is maintained.Update: ;

- Otherwise, a unit step is also performed along .Update: .

| Algorithm 1 Bresenham algorithm in the first octant with a starting point and a direction vector |

| Require: Current cell , direction vector with , , and ; maximum number of steps Ensure: Cells to be successively considered

|

- Case 1—Same sign (; octants 2 and 6).

- Case 2—Opposite sign (; octants 3 and 7).

| Algorithm 2 Generalized Bresenham algorithm for all octants using a starting point and a direction vector |

| Require: Starting point , direction vector , number of iterations Ensure: Cells to be successively considered

|

- Step 4.4—Evaluation of Optical Ray–Terrain Intersection

- Step 4.4.1 Estimation of the Optical Ray Altitude within a DEM Cell

- Step 4.4.2 Maximum Error Bound and Exclusion Zone

- Step 5—Clustering of Geolocated Hotspots and Temperature Aggregation

- Step 6—Results Export

3. Experiment

3.1. Test Sites

3.2. Equipment

3.2.1. Aerial Platforms and Sensors

3.2.2. Image Exclusion Zone Parameters

3.2.3. Hotspot Simulation and Ground Truth

3.2.4. Digital Elevation Models

3.3. Flight Configurations

3.4. Computation and Algorithm Deployment

4. Results

4.1. Step-by-Step Example of DEM Traversal and Stopping Criterion

4.2. Geolocation Performance Metrics

- cluster-size weighted mean of per-cluster point positional errors (Weighted mean pt. error);

- average of per-cluster maximum point positional errors (Max pt. error);

- average centroid positional error (Centroid error);

- maximum of per-cluster mean point positional errors (Max of mean pt. error);

- maximum point positional error among all clusters (Max of max pt. error);

- maximum centroid positional error (Max centroid error).

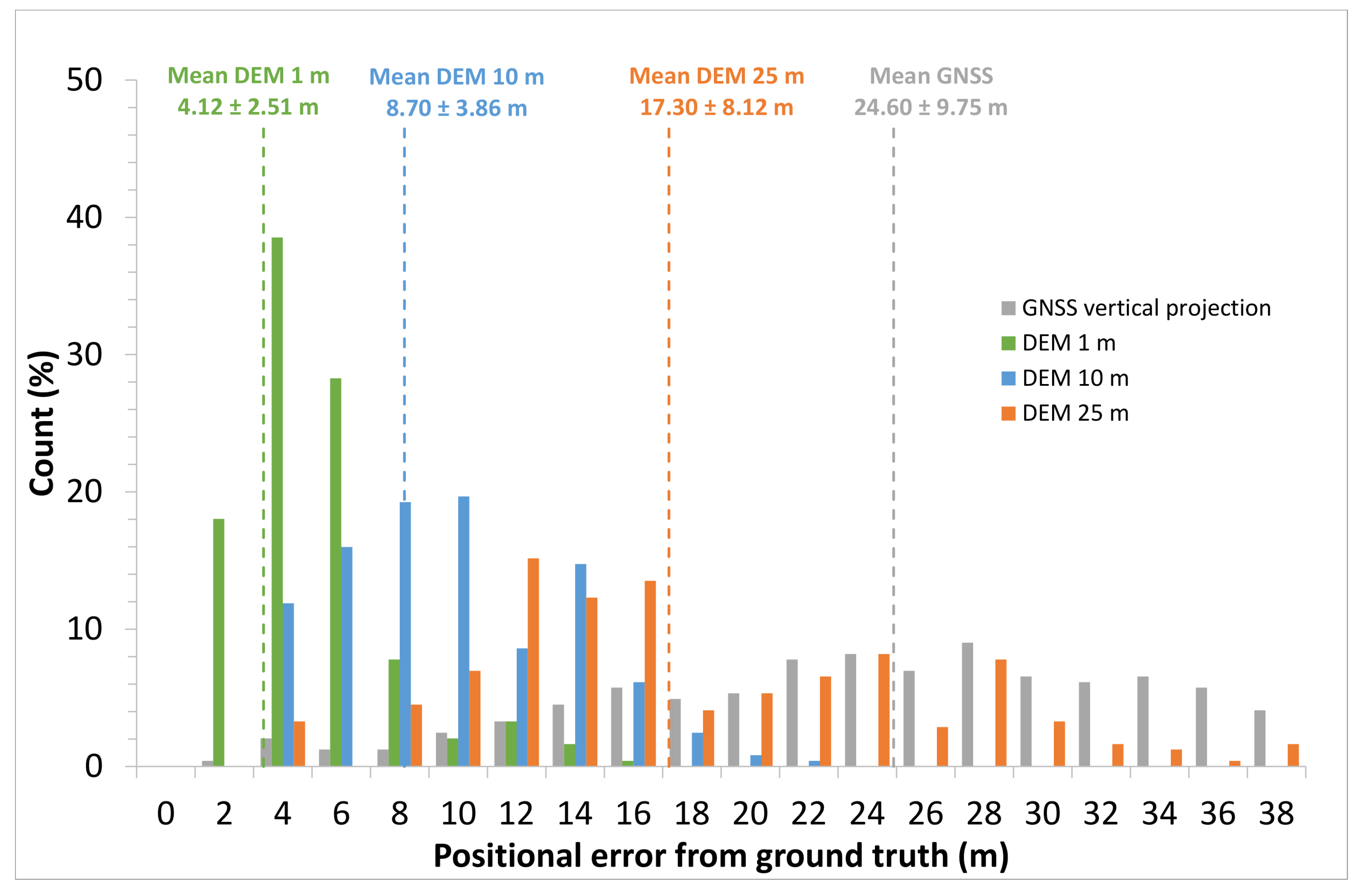

4.3. Effect of DEM Resolution and Comparison with a GNSS Baseline

4.4. Processing Time

4.5. Operational Use in Real Wildfire Events

5. Discussion

5.1. Geolocation Accuracy and Main Experimental Factors

5.2. Effect of DEM Resolution on the Proposed Method and Comparison with the GNSS Vertical-Projection Baseline

5.3. Experimental Limitations and Environmental Constraints

5.4. Processing Efficiency and Operational Deployment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Spreading Like Wildfire—The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment. Nairobi. 2022. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/spreading-wildfire-rising-threat-extraordinary-landscape-fires (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Duchelle, A. Increase in Climate-Driven Wildfires Calls for More Investment in Prevention. UN Denmark. 2024. Available online: https://un.dk/increase-in-climate-driven-wildfires-calls-for-more-investment-in-prevention/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- European Science & Technology Advisory Group (E-STAG). Evolving Risk of Wildfires in Europe: The Changing Nature of Wildfire Risk Calls for a Shift in Policy Focus from Suppression to Prevention; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR): Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.W.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Lasslop, G.; Forkel, M.; Smith, A.J.P.; Burton, C.; Betts, R.A.; van der Werf, G.R.; et al. Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2020RG000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Taming Wildfires in the Context of Climate Change; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Pellegrini, A.; Maestre, F.T.; Seddon, A.W.R.; van der Werf, G.; Canadell, J.G. Climate change is increasing the risk of extraordinary landscape fires. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. Heat Summary—Chapter 10: Wildfires and Health; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/heat-summary-chapter-10-wildfires-and-health (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Carrington, D. Summer Wildfires Increased Fourfold in England in 2022. The Guardian, 30 December 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/30/summer-wildfires-increased-fourfold-in-england-in-2022 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- International Association of Fire and Rescue Services (CTIF). The Biggest Fire in Slovenia’s History: Karst Fire 2022. CTIF, 2023. Available online: https://ctif.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/CTIF%20The%20biggest%20fire.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- European Commission. Report on the Large Wildfires of 2022 in Europe; Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://civil-protection-knowledge-network.europa.eu/system/files/2024-12/report-on-the-large-wildfires-of-2022-in-europe-kjna32034enn.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Reuters. Switzerland Fights to Contain Forest Fire near Italy Border as Winds Pick Up. Reuters. 2023. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/swiss-forest-fire-could-spread-if-winds-pick-up-authorities-warn-2023-07-18/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Le News. Firefighters Continue to Fight Swiss Forest Fire. LeNews. 2023. Available online: https://lenews.ch/2023/07/22/firefighters-continue-to-fight-swiss-forest-fire/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Indian Express. Drought, Rising Heat Bring Unusual Wildfire Warnings in Northern Europe. 19 June 2023. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/world/drought-rising-heat-bring-unusual-wildfire-warnings-northern-europe-8667188/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Arctic Council. Norwegian Chairship Launches Initiative to Address Wildland Fires. 30 May 2023. Available online: https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- La Dépêche. Incendies en Gironde: Un an et demi après, pourquoi le feu couve-t-il toujours dans les sols ? La Dépêche. 2023. Available online: https://www.ladepeche.fr/2023/11/30/incendies-en-gironde-un-an-et-demi-apres-le-brasier-pourquoi-le-feu-couve-t-il-toujours-dans-les-sols-11612692.php (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Préfecture de la Gironde. Incendies en cours en Gironde—Point du 22 juillet 2022. Gouvernement Français. 2022. Available online: https://www.gironde.gouv.fr/Actualites/Communiques-de-presse/Communiques-de-presse-2022/Juillet-2022/Incendies-en-cours-en-Gironde-point-du-22-juillet-2022-a-20h00 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Huijnen, V.; Wooster, M.J.; Kaiser, J.W.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Flemming, J.; Parrington, M.; Inness, A.; Murdiyarso, D.; Main, B.; van Weele, M. Fire carbon emissions over maritime Southeast Asia in 2015 largest since 1997. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turetsky, M.R.; Benscoter, B.; Page, S.; Rein, G.; van der Werf, G.R.; Watts, A. Global vulnerability of peatlands to fire and carbon loss. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolter, M.A.; Vice, D.H. Looking back at the Centralia coal fire: A synopsis of its present status. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2004, 59, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracher, G.B. Coal fires burning around the world: A global catastrophe. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2004, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incendies en Gironde: Des Drones Pour Repérer les Points Chauds Dans la Forêt de Cendre d’Hostens. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=441e1KyNzYI (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Advexure. Firewatch from Above: How Thermal Drones Aid Wildfire Prevention and Response. Advexure Blog. 2025. Available online: https://advexure.com/blogs/news/firwatch-from-above-how-thermal-drones-aid-wildfire-prevention-response (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Fagen, C.; Weir, J.R.; Payne, D. Using Drones with Infrared Capabilities to Monitor Fire Behavior. Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service. NREM-2907. 2021. Available online: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/using-drones-with-infrared-capabilities-to-monitor-fire-behavior.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Iizuka, K.; Watanabe, K.; Kato, T.; Putri, N.A.; Silsigia, S.; Kameoka, T.; Kozan, O. Visualizing the Spatiotemporal Trends of Thermal Characteristics in a Peatland Plantation Forest in Indonesia: Pilot Test Using Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs). Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yang, X.; Luo, Z.; Guan, T. Application of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) thermal infrared remote sensing to identify coal fires in the Huojitu coal mine in Shenmu city, China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Youmin, Z.; Zhixiang, L. A survey on technologies for automatic forest fire monitoring, detection, and fighting using unmanned aerial vehicles and remote sensing techniques. Can. J. For. Res. 2015, 45, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhloufi, M.A.; Couturier, A.; Castro, N.A. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Wildland Fires: Sensing, Perception, Cooperation and Assistance. Drones 2021, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nex, F.; Remondino, F. Preface: Latest Developments, Methodologies, and Applications Based on UAV Platforms. Drones 2019, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailon-Ruiz, R. Design of a Wildfire Monitoring System Using Fleets of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Fédérale Toulouse Midi-Pyrénées, Toulouse, France, 24 September 2020. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-02995471 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Ambrosia, V.G.; Wegener, S.S.; Sullivan, D.V.; Buechel, S.W.; Dunagan, S.E.; Brass, J.A.; Stoneburner, J.; Schoenung, S.M. Demonstrating UAV Acquired Real Time Thermal Data over Fires. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollero, A.; de Dios, J.M.; Merino, L. Unmanned aerial vehicles as tools for forest-fire fighting. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 234, S263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosia, V.G.; Wegener, S.; Zajkowski, T.; Sullivan, D.V.; Buechel, S.; Enomoto, F.; Lobitz, B.; Johan, S.; Brass, J.; Hinkley, E. The Ikhana unmanned airborne system (UAS) western states fire imaging missions: From concept to reality (2006–2010). Geocarto Int. 2011, 26, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkley, E.A.; Zajkowski, T. USDA forest service—NASA: Unmanned aerial systems demonstrations—Publishing the leading edge in fire mapping. Geocarto Int. 2011, 26, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Almeida, J.; Almeida, C.; Figueiredo, A.; Santos, F.; Bento, D.; Silva, H.; Silva, E. Forest fire detection with a small fixed wing autonomous aerial vehicle. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2007, 40, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, L.; Caballero, F.; Martínez-de Dios, J.R.; Ferruz, J.; Ollero, A. A cooperative perception system for multiple UAVs: Application to automatic detection of forest fire. J. Field Robot. 2006, 23, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailon-Ruiz, R.; Lacroix, S. Wildfire remote sensing with UAVs: A review from the autonomy point of view. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffre, F.; Hildmann, H.; Karvonen, H.; Lind, T. Monitoring and Cordoning Wildfires with an Autonomous Swarm of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2022, 6, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, E.; Barrado, C.; Royo, P.; Santamaria, E.; Lopez, J.; Salami, E. Architecture for a helicopter-based unmanned aerial systems wildfire surveillance system. Geocarto Int. 2011, 26, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthinathan, P.; Amarasingam, N.; Hamilton, G.; Gonzalez, F. Exploring unmanned aerial systems operations in wildfire management: Data types, processing algorithms and navigation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 5628–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.B.; Yotsumata, T.; El-Sheimy, N. Real time identification and location of forest fire hotspots from geo-referenced thermal images. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2004, 35, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Graml, R.; Grant, W. Bushfire Hotspot Detection Through Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles and Reconfigurable Computing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–8 March 2008; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, R.; Johnston, J.M.; Craig, G.; Jennings, S. Airborne Optical and Thermal Remote Sensing for Wildfire Detection and Monitoring. Sensors 2016, 16, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viseras, A.; Marchal, J.; Schaab, M.; Pages, J.; Estivill, L. Wildfire Monitoring and Hotspots Detection with Aerial Robots: Measurement Campaign and First Results. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR), Würzburg, Germany, 2–4 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Bohdanov, D.; Liu, H.H.T.; Wotton, M. Autonomous wildfire hotspot detection using a fixed wing UAV. Int. J. Aerosp. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y.; Qiao, P.; Zhao, J. Review of Target Geo-Location Algorithms for Aerial Remote Sensing Cameras without Control Points. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitted, T. An improved model for shaded display. Comun. ACM 1980, 23, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresenham, J.C. Algorithm for Computer Control of a Digital Plotter. IBM Syst. J. 1965, 4, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgouyres, R. Algorithmes pour la Synthèse D’images et L’animation 3D; Dunod: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R.T.; Tsin, Y.; Miller, J.R.; Lipton, A.J. Using a DEM to determine Geospatial Object Trajectories. In DARPA Image Understanding Workshop; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, B.; Cherif, E.K.; Bernardino, A.; Ribeiro, R. Real-Time Georeferencing of Fire Front Aerial Images Using Iterative Ray-Tracing and the Bearings-Range Extended Kalman Filter. Sensors 2022, 22, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Arfaoui, W. Wildfire Mapping Using Infra-Red Images Acquired by a Drone; Trainee Report; INP-ENSEEIHT: Toulouse, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DJI. Zenmuse H20 Series v1.2; SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd.: Shenzhen, China, 2021; Available online: https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/Zenmuse_H20_Series/20200824/Zenmuse_H20_Series_User_Manual-EN.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- DJI. Matrice 30 Series User Manual v2.2. 2024. Available online: https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/matrice-30-series/20230922UM/Matrice30_Series_User_Manual_v2.0_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- TERIA. Fiche Technique Récepteur GNSS PYX. 2022. Available online: https://www.reseau-teria.com/wp-content/uploads/fiche-technique-pyx.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Institut National de l’information Géographique et Forestière (IGN). RGE ALTI®—Référentiel à Grande Échelle Altimétrique. Available online: https://geoservices.ign.fr/rgealti (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- NGF-IGN 1978; Nivellement Général de la France—Réseau de Corse. IGN: Saint-Mandé, France, 1978.

- NGF-IGN 1969; Nivellement Général de la France—Réseau de Base. IGN: Saint-Mandé, France, 1969.

- Institut National de l’information Géographique et Forestière (IGN). BD ALTI®—Base de Données Altimétrique. Available online: https://geoservices.ign.fr/bdalti (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- SPH Engineering. Flight Planning Software for UAV Missions. Available online: https://www.sphengineering.com/flight-planning (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- The GOLIAT Project. Available online: https://goliat.universita.corsica/?lang=en (accessed on 15 July 2025).

| Quantity | Value |

|---|---|

| Drone GNSS (lat, lon, alt) | 42.3467572862583 °N, 9.14679921234292 °E, 824.842 m (WGS84) |

| Origin DEM cell (indices) | |

| Origin DEM cell [m] | 1,206,826.0, 6,158,264.0 (Lambert–93; bottom-left) |

| 2D direction | |

| Incidence angle |

| k | z-Terrain (m) | -Optical Ray (m) | (m) | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | (0,0) | 714.4 | 773.9 | 59.5 | continue |

| 1 | (−1,0) | 713.7 | 770.2 | 56.5 | continue |

| 2 | (−2,0) | 712.9 | 766.4 | 53.5 | continue |

| 3 | (−3,0) | 712.4 | 762.7 | 50.3 | continue |

| 4 | (−4,0) | 711.9 | 758.9 | 47.0 | continue |

| 5 | (−5,−1) | 711.4 | 754.8 | 43.4 | continue |

| 6 | (−6,−1) | 710.8 | 751.1 | 40.3 | continue |

| 7 | (−7,−1) | 710.2 | 747.4 | 37.2 | continue |

| 8 | (−8,−1) | 709.6 | 743.6 | 34.0 | continue |

| 9 | (−9,−1) | 708.9 | 739.9 | 31.0 | continue |

| 10 | (−10,−1) | 708.2 | 736.2 | 28.0 | continue |

| 11 | (−11,−1) | 707.6 | 732.4 | 24.8 | continue |

| 12 | (−12,−1) | 706.9 | 728.7 | 21.8 | continue |

| 13 | (−13,−2) | 706.3 | 724.5 | 18.2 | continue |

| 14 | (−14,−2) | 705.7 | 720.8 | 15.1 | continue |

| 15 | (−15,−2) | 705.1 | 717.0 | 11.9 | continue |

| 16 | (−16,−2) | 704.5 | 713.3 | 8.8 | continue |

| 17 | (−17,−2) | 704.0 | 709.6 | 5.6 | continue |

| 18 | (−18,−2) | 703.5 | 705.9 | 2.4 | continue |

| 19 | (−19,−2) | 702.8 | 702.1 | −0.7 | stop |

| UAV | Means [m] | Max [m] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Mean pt. | Max pt. | Centroid | Mean pt. | Max pt. | Centroid | |

| M300 without RTK | 3.6 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 4.0 |

| M30T without RTK | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 3.8 |

| UAV | Means [m] | Max [m] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Mean pt. | Max pt. | Centroid | Mean pt. | Max pt. | Centroid | |

| M300 with RTK | 3.1 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 3.7 |

| M300 without RTK | 3.3 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 3.9 |

| M30T without RTK | 4.7 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 5.7 | 9.7 | 5.4 |

| UAV | Means [m] | Max [m] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Mean pt. | Max pt. | Centroid | Mean pt. | Max pt. | Centroid | |

| M300 with RTK | 3.5 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 12.6 | 4.5 |

| M30T without RTK | 4.8 | 7.0 | 3.5 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 6.6 |

| Height (m) | Method | Mean (m) | SD (m) | Min (m) | Max (m) | CEP95 (m) | CEP50 (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 1 m DEM | 3.15 | 1.77 | 0.91 | 11.86 | 6.06 | 2.92 |

| 10 m DEM | 7.86 | 3.71 | 3.13 | 20.03 | 14.43 | 7.10 | |

| 25 m DEM | 17.80 | 7.57 | 2.27 | 37.01 | 31.24 | 16.01 | |

| GNSS vertical projection | 13.40 | 5.72 | 0.92 | 25.47 | 23.11 | 13.45 | |

| 120 | 1 m DEM | 4.12 | 2.51 | 1.04 | 14.04 | 10.39 | 3.77 |

| 10 m DEM | 8.70 | 3.86 | 3.13 | 21.99 | 15.68 | 8.07 | |

| 25 m DEM | 17.30 | 8.12 | 2.27 | 46.45 | 30.47 | 14.81 | |

| GNSS vertical projection | 24.60 | 9.75 | 0.79 | 48.00 | 40.25 | 25.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rossi, L.; Morandini, F.; Burglin, A.; Bertrand, J.; Wandon, C.; Tollard, A.; Pieri, A. DEM-Based UAV Geolocation of Thermal Hotspots on Complex Terrain. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3911. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233911

Rossi L, Morandini F, Burglin A, Bertrand J, Wandon C, Tollard A, Pieri A. DEM-Based UAV Geolocation of Thermal Hotspots on Complex Terrain. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3911. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233911

Chicago/Turabian StyleRossi, Lucile, Frédéric Morandini, Antoine Burglin, Jean Bertrand, Clément Wandon, Aurélien Tollard, and Antoine Pieri. 2025. "DEM-Based UAV Geolocation of Thermal Hotspots on Complex Terrain" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3911. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233911

APA StyleRossi, L., Morandini, F., Burglin, A., Bertrand, J., Wandon, C., Tollard, A., & Pieri, A. (2025). DEM-Based UAV Geolocation of Thermal Hotspots on Complex Terrain. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3911. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233911