1. Introduction

Glaciers are sensitive indicators of regional climate forcing, exhibiting dynamic responses to variability in air temperature and precipitation. Monitoring these responses is essential for quantifying cryospheric change and its implications for sea-level rise, regional water resources, and climate feedbacks [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In the Canadian high Arctic, logistical constraints and severe environmental conditions limit field observations. Although the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (CAA) hosts the largest glacierized area outside the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, sustained in situ mass balance records remain sparse, hindering robust regional assessments and the evaluation of climate models that require reliable observational constraints [

5,

6].

Satellite remote sensing provides synoptic observations of glacier surfaces via the following two key metrics: the snow cover ratio (SCR) and snowline altitude (SLA) [

7,

8,

9]. These serve as proxies for the field-derived accumulation-area ratio (AAR) and equilibrium-line altitude (ELA), respectively. While SCR and SLA represent transient states, they approximate the annual AAR and ELA when derived from imagery captured at the end of the ablation season. Multi-temporal analyses exploit the established monotonic relationships between these metrics to infer interannual mass balance variability and climatic controls across diverse settings [

7,

9,

10].

Despite their utility, the delineation of the SCR and SLA from satellite imagery remains challenging. Manual mapping is labour intensive (often requiring hours of expert analysis per scene) and is subject to operator variability that can introduce vertical uncertainties exceeding the sensor resolution [

7,

11]. Automated approaches, such as Otsu thresholding and the Automatic Snowline Mapping and Glacier delineation (ASMAG) workflow, reduce manual effort but rely on empirical thresholds (e.g., SCR = 0.5) that can underestimate ELA relative to in situ observations (

Figure 1) [

7,

11,

12]. Elevation binning (Bin) methods further introduce uncertainty through sensitivity to bin size, threshold selection, and post processing choices [

7,

12]. Alternatively, the snowline pixel elevation histogram (SPEH) method estimates SLA directly from the distribution of snow–ice boundary pixel elevations, but its performance across glacier geometries and melt conditions has not been systematically evaluated.

Machine learning (ML) approaches provide adaptive classification capabilities essential for analyzing large, high-dimensional datasets such as Sentinel-2 satellite image time series (SITS) [

13]. However, the application of ML in glaciology is frequently constrained by the scarcity of labelled training data. Collecting ground truth for snow and ice in remote Arctic environments is logistically prohibitive, making fully supervised models difficult to implement without extensive manual annotation [

11,

14].

To address this limitation, a practical strategy is to couple unsupervised clustering with supervised classification. In this framework, K-means clustering partitions the spectral data into coherent groups (pseudo labels), which then serve as training targets for ensemble classifiers like Random Forest (RF) or Support Vector Machines (SVMs). By treating statistically coherent spectral clusters as proxy ground truth, this method automates the generation of training samples and eliminates the bottleneck of human digitization. Recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this approach as follows: Nambiar et al. [

15] achieved high accuracy in semantic segmentation using self training, while Mirpulatov et al. [

16] showed that K-means-derived pseudo-labels substantially improve land cover classification in data-sparse regions.

The objectives of this study are therefore threefold as follows:

Develop an operational integrated workflow that couples unsupervised K-means clustering (for automated pseudo-label generation) with supervised classification, thereby eliminating the need for manual training data in data-sparse regions.

Evaluate the efficacy of statistical SLA extraction methods (SPEH vs. elevation binning) and demonstrate that a high-threshold binning strategy () is required to mitigate mixed-pixel errors inherent in Sentinel-2 imagery.

Validate the end-to-end pipeline against the long-term in situ mass balance record of White Glacier, quantifying the physical agreement between the satellite-derived SLA and the field-measured ELA.

This methodological integration offers the following distinct advantage over existing approaches: it eliminates the reliance on manual training data while simultaneously mitigating the mixed pixel bias that limits standard automated thresholding. This approach builds upon recent semi-supervised segmentation studies [

14,

15] by extending the analysis beyond classification accuracy to physical glaciological validation. This study develops a scalable hybrid ML workflow for White Glacier in the Canadian high Arctic, a benchmark glacier with continuous mass balance records since 1960. By quantifying SCR and SLA over melt seasons and comparing these with in situ mass balance-derived ELA, the approach seeks to improve the reliability of remote sensing-based glacier monitoring and reduce uncertainties associated with manual classification and empirical thresholding.

2. Study Site

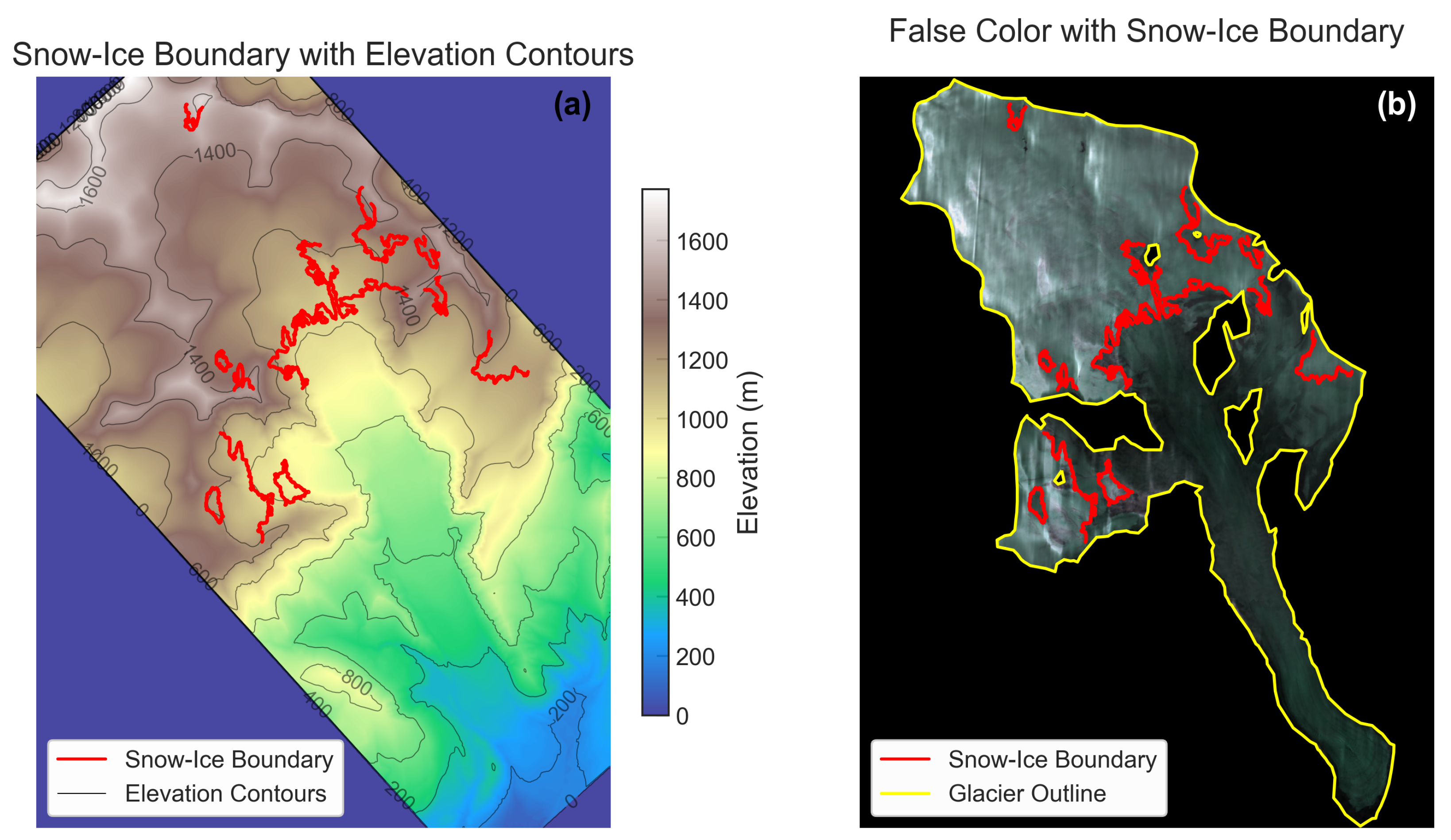

White Glacier, located on the southern margin of Axel Heiberg Island in the Canadian high Arctic (79.75°N, 90.67°W;

Figure 2), is a benchmark reference site within the Global Terrestrial Network for Glaciers (GTN-G). Continuous mass balance observations have been maintained since 1960, providing one of the longest unbroken cryospheric records in the high Arctic. These data, including annual ELA and AAR metrics, are archived by the World Glacier Monitoring Service [

17] and support regional assessments of climate-driven change.

The glacier is named for its distinctively bright, debris-free ice surface. The ablation period (typically July–August) is characterized by significant surface melt in the glacier’s lower zones, exposing bare ice and intensifying mass loss. This seasonal transition is a key driver of snowline dynamics and mass balance state observable via remote sensing [

7,

8].

White Glacier is a valley glacier extending from 1782 m above sea level at its maximum to 85 m at its terminus. The glacier is characterized by minimal supraglacial debris and an open valley geometry that reduces topographic shading in the ablation zone. These physical attributes minimize spectral ambiguity, rendering White Glacier a suitable testbed for validating optical classification algorithms. Over the past six decades, it has experienced a significant retreat, shrinking from an area of 41.07 km

2 in 1960 to 38.54 km

2, underscoring its sensitivity to regional climatic variations [

18]. The glacier is situated in an environment with a mean annual temperature of approximately −20 °C. Precipitation in the region ranges from 58 mm per year at sea level, as recorded at Eureka (100 km to the east), to 370 mm per year at 2120 m above sea level [

18]. These climatic and environmental conditions, frequented by cloud-free skies during key periods, provide a well-suited setting for optical and multispectral remote sensing analyses.

4. Method

This study proposes a hybrid, semi-supervised machine learning framework designed to overcome the scarcity of ground-truth training data in glacial environments. The workflow integrates unsupervised clustering with supervised classification to automate the delineation of the SLA from high-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the methodology comprises the following four primary algorithmic stages: (1) data acquisition and pre-processing; (2) unsupervised K-means clustering to generate pseudo-labels; (3) supervised snow–ice classification guided by the pseudo-labels; and (4) annual SLA delineation using the minimum-SCR date.

4.1. Stage 1: Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

Sentinel-2 Level-1C top-of-atmosphere reflectance data were acquired for White Glacier via the Google Earth Engine (GEE) application programming interface (API). The temporal analysis window was restricted to the ablation season (15 June–31 August) to capture the maximum retreat of the snowpack. Scenes exhibiting cloud cover > were discarded. For every valid acquisition, the native 10 m bands—blue (B2), green (B3), red (B4), and near-infrared (B8)—were extracted to characterize the glacial surface.

4.2. Stage 2: Unsupervised K-Means Clustering and Pseudo-Labelling

To prepare the spectral data for unsupervised labelling, a feature vector

x was constructed for each pixel

i. To mitigate spectral redundancy and computational cost prior to clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied, retaining the first two principal components (

). The high-dimensional spectral space

was projected onto a lower-dimensional subspace

containing the two principal components as follows:

where

X is the centred data matrix and

is the matrix of the top

eigenvectors. While PC1 (>

variance) captures the dominant albedo signal, PC2 (

variance) was retained because it encodes the spectral contrast between visible and near-infrared wavelengths. This chromatic information is essential for distinguishing surface types with similar brightness but different physical properties (e.g., wet snow vs. clean ice) [

25,

26].

To generate training samples without manual annotation, the workflow employs K-means clustering on the PCA-transformed feature space. The algorithm partitions the pixel set into

clusters. Although a statistical Elbow Method analysis suggested an inertia plateau at

, empirical validation demonstrated that this configuration failed to resolve critical internal snowpack variance, often conflating wet snow with ice. Consequently,

was selected as the optimal configuration to distinguish between Ground, Ice, and two spectral states of Snow. This choice ensures the separation of distinct snow facies (

Table 2), which are later aggregated into a single ‘Snow’ class—without over-segmenting the ‘Ground’ class. The objective function

J is defined as follows:

where

represents a pixel vector assigned to cluster

j, and

is the centroid of cluster

j. The resulting cluster assignments serve as ‘pseudo-labels’, providing an initial structural estimation of surface classes. To ensure the distinctness of these clusters prior to their use as ground truth, the Silhouette Coefficient (

s) was computed for each sample.

Class Balancing and Resampling

Glacial environments exhibit inherent class imbalance, where dominant classes (e.g., Ground or Ice) can vastly outnumber specific snow facies. To mitigate this bias and optimize training data for the subsequent supervised classifier, three resampling approaches were evaluated as follows:

Random Resampling: Samples were selected randomly from each cluster without regard for distribution.

Stratified Resampling: This approach ensured the proportional representation of each cluster based on its size. By maintaining a balance among clusters, stratified resampling effectively addresses the imbalance problem.

Cluster Resampling: A random subset of samples was extracted within each cluster, capping the maximum number of samples from larger clusters to mitigate their dominance while preserving sufficient variability.

All resampling methods were implemented with a fixed training set size of 100,000 pixels. Empirical evaluations of these resampling strategies were conducted by analyzing key performance metrics, such as accuracy and F1-score, in the final supervised classification task.

4.3. Stage 3: Supervised Snow–Ice Classification

The pseudo-labels generated in Stage 2 served as training targets for the supervised classification stage. The workflow employs a RF classifier, utilizing an ensemble of

B decision trees to mitigate overfitting. For an input vector

x, the RF prediction

is determined by the mode of the ensemble output as follows:

where

is the prediction of the

b-th tree. The model was configured with

trees and a maximum depth of 10. To ensure temporal consistency and minimize overfitting to specific atmospheric conditions, the training dataset was constructed using sampling from the entire 2019–2024 image time series. This generated a global spectral feature space, ensuring that the classifier learned decision boundaries robust to interannual variability. A SVM was also implemented as a comparative baseline.

Training the classifier on K-means outputs functions as a knowledge distillation process. Rather than predicting independent ground truth, the RF is designed to learn a robust, generalized decision boundary that reproduces the spectral partitioning of the global K-means model across the full spatial extent of the glacier.

Classification performance was evaluated through standard metrics including hlreproduction fidelity (agreement with pseudo-labels), confusion matrices, and the F1-score. The F1-score was prioritized as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing robustness against false positives and negatives in imbalanced datasets as follows:

Beyond numerical metrics, a visual comparison was conducted by overlaying the classification results on composite Sentinel-2 images to assess spatial accuracy and contextual relevance.

4.4. Stage 4: Annual End-of-Ablation SCR and SLA Delineation

The trained classifier was applied to the full Sentinel-2 time series. For each scene, the SCR was computed as follows:

where

N represents the pixel count within the glacier mask. The date corresponding to the seasonal minimum SCR (

) was identified as the end-of-ablation epoch. To derive the SLA from the

image, two complementary hypsometric methods were implemented.

- 1.

Statistical Mode (SPEH)

Adapted from Aberle et al. [

27], this method analyses the frequency distribution of the snow–ice boundary. A binary classification mask was generated to separate snow/ice pixels from non-glacial surfaces. The snow–ice boundary was then refined with a two-step morphological procedure (dilated ice mask intersection followed by morphological erosion) to suppress edge artifacts.

To minimize noise and ensure physiographic relevance, snow–ice boundary segments containing fewer than 100 valid boundary pixels or occurring below 900 m a.s.l. were excluded from analysis. The 100-pixel filter removes “salt-and-pepper” classification noise (≈1 ha), while the 900 m elevation floor is based on the long-term mass balance record of White Glacier, which indicates that the ELA has consistently remained above this altitude. This constraint prevents the algorithm from erroneously identifying late-lying snowbanks or river icing (aufeis) in the terminus zone as the snowline.

Elevation for the refined boundary pixels was sampled from ArcticDEM v4.1, co-registered to the Sentinel-2 imagery and resampled to the same 10 m grid. Pixels with invalid or missing elevations (NaN) were removed prior to subsequent analyses.

Boundary pixels transitioning from snow to ice were extracted, and their elevations (derived from co-registered ArcticDEM v4.1) were grouped into 5 m intervals to construct a histogram

. The SLA was defined as the mode of this distribution as follows:

This metric was chosen for its robustness against outliers and localized classification noise, offering a stable estimate that reflects the dominant elevation of the snow–ice transition zone (

Figure 4).

- 2.

Elevation Binning ()

Adapted from Rastner et al. [

7], this method relies on discretizing the glacier hypsometry into elevation bins

b of height

m. For each bin, a local SCR (

) was calculated as the proportion of snow-covered pixels relative to the total number of ice-and-snow pixels in that bin. The SLA was determined as the lowest elevation bin where the snow cover consistently exceeds a threshold

as follows:

where

was tested at 0.5 and 0.8. The threshold

was selected as a baseline following standard automated protocols (e.g., ASMAG; [

7]). The stricter threshold

was introduced to enforce a higher fraction of snow within the elevation bin. This conservative threshold acts as a filter for the spatially coherent snowline, rejecting transitional zones (e.g., patchy firn or mixed pixels) that frequently trigger false positives at lower thresholds.

Validation and Visualization

Delineated snowlines were validated by overlaying the mapped snow–ice boundary on ArcticDEM topography and on Sentinel-2 false-colour composites to confirm consistency with observed surface features (

Figure 5). Independent validation was performed by comparison with annual, in situ field-derived ELA. This combined approach, comprising visual inspection against topography and imagery alongside a comparison to field-derived ELA, supports the reliability of the SLA estimates.

4.5. Uncertainty Assessment

Multiple factors contribute to the overall uncertainty in the SLA estimates derived for White Glacier in this study, outlined as follows:

4.5.1. DEM Vertical Accuracy

This study utilizes the ArcticDEM Version 4.1 dataset, which has a reported vertical accuracy of approximately m. It is important to note that this value might not fully reflect local variations due to differences in topography, slope, or satellite viewing angles, potentially leading to localized inaccuracies in SLA estimation.

4.5.2. Statistical Variability in Snow–Ice Boundary Delineation

The snow–ice boundary was aggregated into 5 m elevation bins for SLA metric calculation. While this method mitigates the impact of minor outliers, it introduces an inherent variability of up to m (half the bin size). This binning strategy might obscure subtle transitions at the boundary, thus adding to the uncertainty in precise SLA determination.

4.5.3. Temporal Offset Between DEM and Imagery

A significant source of uncertainty arises from the temporal mismatch between the ArcticDEM V4.1 mosaic, covering 2011 to 2021, and the more recent Sentinel-2 imagery used for snowline detection. Elevation dynamics relating to thinning, accumulation, and mass transfer through the glacier system during this period could introduce discrepancies in elevation data. However, these unquantified shifts are excluded from uncertainty calculations, as their effect is deemed minor compared to other sources and challenging to measure.

4.5.4. Combined Uncertainty Calculation

The combined vertical uncertainty for the SLA is expressed using a root-sum-square approach that incorporates the known error sources. The equation is given by the following:

where the following hold:

is the total SLA uncertainty from the known vertical and binning error sources.

is the vertical accuracy of the ArcticDEM (approximately m).

is half the width of the 5 m elevation bin used for statistical aggregation (i.e., m).

Substituting the known values into the equation

Thus, based on the known vertical accuracy of the DEM and the binning strategy for delineating the snow–ice boundary, the combined uncertainty is approximately m.

5. Results

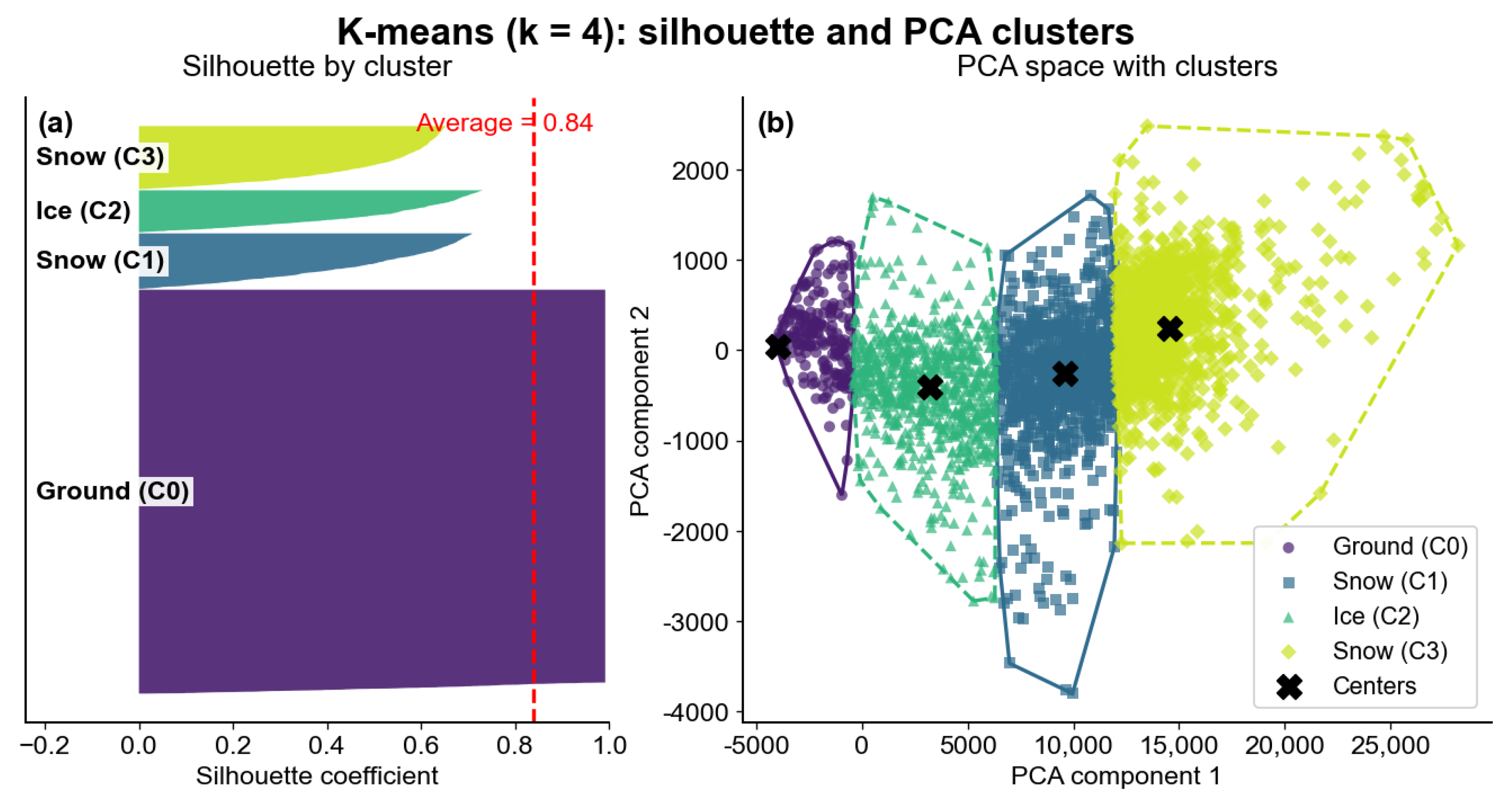

5.1. Dimensionality Reduction and Variance Retention for the Pseudo-Labels

The four-band Sentinel-2 feature space—blue (B2), green (B3), red (B4) and near-infrared (B8) reflectance, all at 10 m—was reduced to two principal components (PCs) using PCA. The first two PCs retained 99.96% of the variance (PC1: 99.65%; PC2: 0.31%), indicating negligible information loss for subsequent clustering and classification. Given the strong inter-band correlation, PCA primarily reoriented the feature space into (i) a broadband albedo axis and (ii) a minor chromatic contrast. PC1, accounting for 99.65% of the variance, represents an albedo gradient as follows: high values correspond to bright snow or clean ice, while low values indicate darker surfaces such as debris-covered ice or exposed ground. PC2 captures a weak contrast between visible and near-infrared reflectance, marginally enhancing separability among bright surfaces (e.g., wet/coarse versus dry/fine snow). The clustering structure shown in

Figure 6b is predominantly resolved along PC1, suggesting a near-univariate decision boundary.

K-means clustering with

on the PCA scores yielded compact, well-separated groups (mean silhouette coefficient

;

Figure 6). Class labels were assigned post hoc based on spectral characteristics and image context. The emergence of two distinct snow clusters (Cluster 1 and Cluster 3) validates the choice of

. These clusters likely capture internal variance within the snowpack, such as the transition between fine-grained dry snow and coarse-grained wet snow, or differences in surface illumination. This separation provides a more refined training target for the supervised classifier than a monolithic “snow” class. A summary of cluster populations is provided in

Table 2.

5.2. Pseudo-Label Resampling and Classifier Performance

The comparative analysis of three resampling methods—Random Resampling, Cluster Resampling, and Stratified Resampling—on the performance of RF and SVM classifiers is summarized in

Table 3. The metrics reported here represent the reproduction fidelity of the supervised models relative to the K-means pseudo-labels, rather than the accuracy against independent ground truth. All methods achieved high fidelity (>0.999) and perfect F1-scores (1.00) for both RF and SVM classifiers. This indicates that the supervised models successfully learned the spectral partitioning defined by the unsupervised clustering. Cluster Resampling slightly outperformed the others with a RF fidelity of 0.999 and was the fastest in terms of RF classification time at 1.7 s. In contrast, SVM classification times were substantially longer, ranging from 113.6 s for Random Resampling to 159.2 s for Cluster Resampling. This suggests that while the resampling method impacts clustering quality, it has minimal effect on classification performance, with computational efficiency being a distinguishing factor, particularly highlighting the efficiency of RF over SVM.

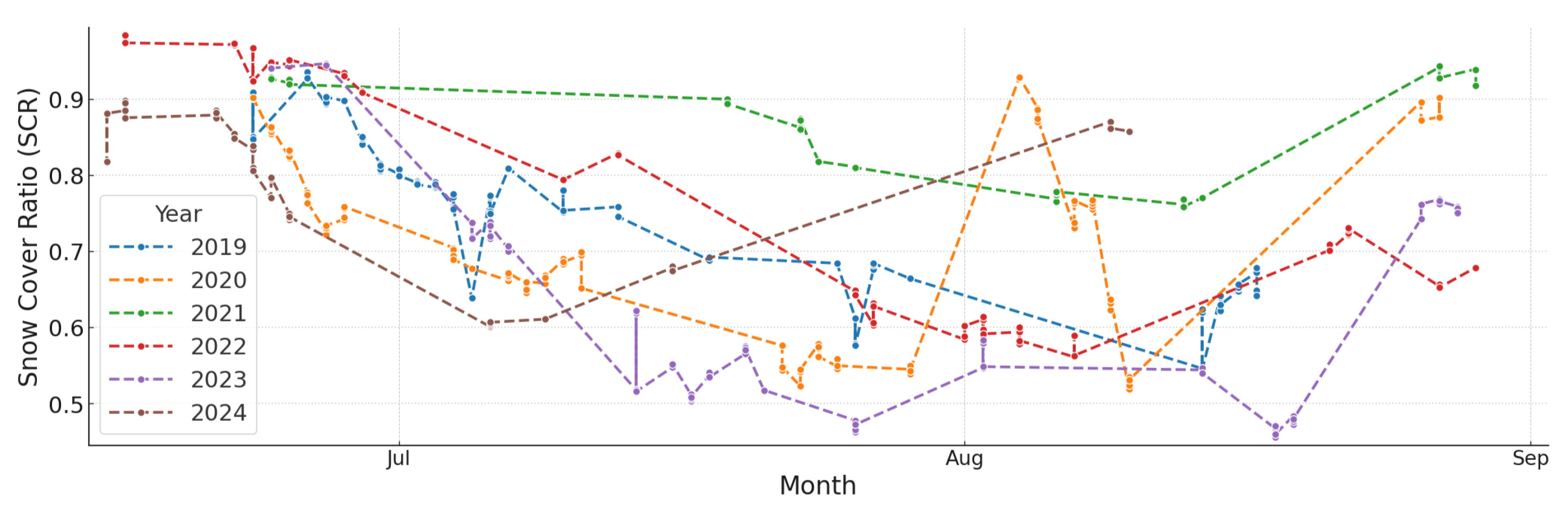

5.3. SCR Trends and SLA Variability

The analysis of White Glacier for 2019––2024 shows pronounced interannual variability in both SCR and SLA, reflecting sensitivity to summer weather (

Figure 7). The annual minimum SCR (end of ablation season) ranged from 0.46 in 2023 to 0.76 in 2021, with minimum-SCR dates varying from 18 August 2023 to 6 July 2024.

The interannual variability tracks regional climatic forcing. The anomalous conditions of 2021, characterized by the highest SCR (0.76) and lowest SLA (967 m), correspond to a regionally documented cool summer with persistent cloud cover and suppressed ablation. Conversely, the low SCR (0.46) and high SLA (1132 m) observed in 2023 reflect a high-melt season driven by elevated summer air temperatures and extended clear-sky conditions. This inverse relationship between SCR and thermal forcing underscores the sensitivity of White Glacier’s accumulation area to summer temperature anomalies.

Interpretation for 2024 is constrained by the limited image availability during the melt season. Field observations indicated an early onset of summer-like conditions, consistent with the early-season SCR decline, followed by unseasonably cool weather and intermittent snowfall that increased SCR. Overall, summer 2024 was unusually cool relative to other study years.

Table 4 summarizes end-of-season SCR, field-measured AAR, and SLA for 2019–2024. Interannual variability in both snow cover and snowline position is pronounced, reflecting changing summer ablation conditions.

The minimum SCR declined from 0.54 (2019) to 0.46 (2023) before rebounding to 0.60 in the partial 2024 record. Consistently, field AAR peaked at 0.62 in 2021—coincident with the greatest snow retention—and fell to 0.20 in 2023, indicating an extensive ablation area.

SPEH-derived SLAs ranged from

m in 2021 to

m in 2020. Lower SCR/AAR years generally correspond to higher SLAs, consistent with the inverse relationship between accumulation area and snowline height. In 2023, the lowest SCR (0.46) and AAR (0.20) coincided with a high

and the highest field ELA (1380 m), indicating strong melt (see also

Figure 8).

at thresholds of 0.5 and 0.8 fall within 20–200 m of the SPEH values. For example, in 2023 the Bin 0.5 SLA is 37 m below the SPEH mode, whereas Bin 0.8 closely matches the field-derived ELA. Agreement among , , and ELA supports the robustness of the snowline delineation framework.

Overall, years with reduced snow cover and accumulation (e.g., 2020 and 2023) produced markedly elevated snowlines, while years with greater accumulation (e.g., 2021) yielded lower snowlines. The close correspondence between remotely-sensed SLA ( and ) and in situ ELA validates the efficacy of the snowline extraction methods for White Glacier.

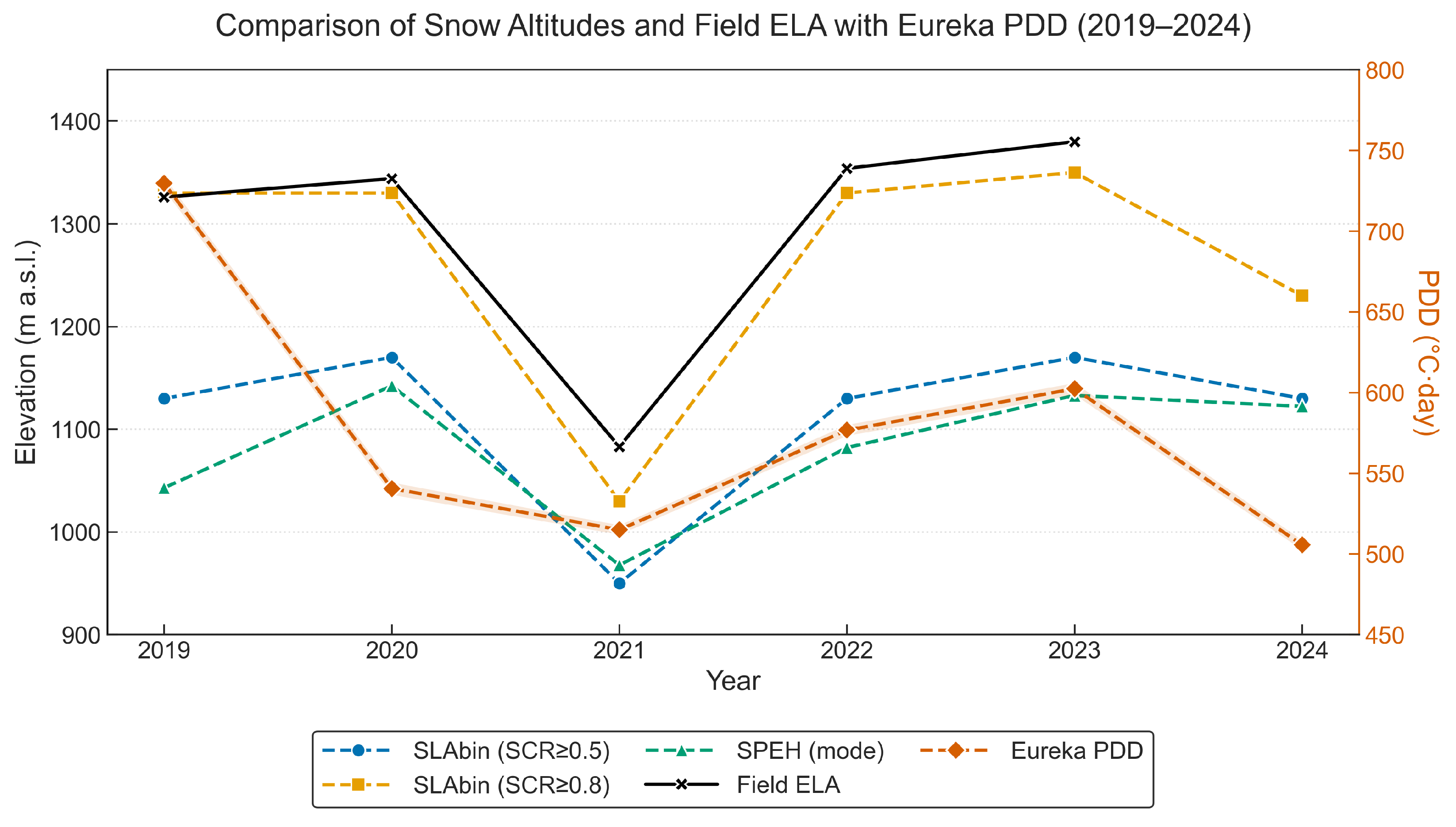

5.4. Comparison of Fieldwork-Derived ELAs and Remote Sensing SLAs

The accuracy of remote sensing-based snowline extraction was assessed by comparing SLA from the SPEH and from elevation-bin method; thresholds

and

with field-derived ELAs for 2019–2023 (

Figure 8;

Table 5). All methods show strong positive correlations with in situ ELA, indicating that interannual variability in snowline position is captured effectively. SPEH yields

(

). The elevation-bin method strengthens as the threshold increases, with

(

) for

and

(

) for

. The near-perfect agreement at

suggests that high snow cover thresholds most reliably isolate the true snow–ice transition.

Root-mean-square error (RMSE) and Mean Bias Error (MBE) further differentiate the methods. SPEH shows the largest deviation (RMSE = 231.9 m). The elevation-bin method at reduces RMSE to 190.1 m but it exhibits a large negative bias ( m). The method at yields the best performance, with the lowest RMSE (30.0 m). However, it is notable that even at this high threshold, the SLA systematically underestimates the ELA (SLA < ELA) with an MBE of m. This consistent negative offset suggests that the satellite-derived snowline generally sits slightly lower in elevation than the mass-balance equilibrium line.

5.5. Relation to Interannual Climate Forcing

To examine climatic forcing, annual PDD sums (°C·d) at Eureka were compared with snowline metrics (

,

and field-derived ELA) (

Figure 8;

Table 5 and

Table 6). PDD peaks in 2019 (729.6 °C·d) and reaches its minimum in 2024 (505.6 °C·d). These thermal maxima and minima broadly mirror the snowline variability: high PDD years (2019, 2023) coincide with elevated SLAs, while low thermal forcing (2021, 2024) corresponds to extensive snow retention (

Figure 8). Pearson correlations over 2019–2024 show weak-to-moderate positive associations between PDD and

, strongest for

(

,

,

), and weaker for

(

,

,

);

shows little linear association (

,

,

). For field-derived ELAs (2019–2023 only), the association is positive but not significant (

,

,

) (

Table 6). The modest correlations likely reflect the short record length, spatial representativeness of Eureka as a proxy for White Glacier, and additional controls (accumulation/precipitation, winds, and late-season cloud/snow affecting SLA retrievals). A longer record and a closer-site temperature index would improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

6. Discussion

The integration of a hybrid machine learning approach, combining K-means-derived pseudo-labels with a RF classifier, has demonstrated efficacy in accurately delineating the annual SCR and SLA on White Glacier. This approach highlights both significant advantages and inherent limitations that should guide its refinement and broader application in glaciological monitoring.

6.1. Advantages and Limitations of Hybrid ML in Glacier Monitoring

The primary advantage of this hybrid framework is its reduced reliance on extensive field-validated datasets, addressing a persistent limitation in Arctic remote sensing [

11,

14]. By applying K-means clustering to the full Sentinel-2 spectral dataset, the workflow generates a large volume of pseudo-labels. This approach significantly decreases the need for labour-intensive manual annotation.

Furthermore, the unsupervised clustering effectively captures within-class variability across surface types such as snow, ice, and debris. This process yields spectrally representative training data for the RF classifier, which subsequently achieved a reproduction fidelity exceeding 99.9%. These results are consistent with observed surface conditions and highlight the computational efficiency of the RF model compared to SVM; notably, RF classification runtimes were reduced by an order of magnitude.

Despite these advantages, a limitation of this approach is the reliance on pseudo-labels for training and evaluation. The high classification metrics reported (

Table 3) indicate that the RF model effectively reproduces the K-means spectral clustering, but they do not quantify pixel-level errors against independent, manually digitized ground truth. Consequently, the physical validity of the classification relies on the downstream agreement between the derived SLA and the field-measured ELA (

Table 5), rather than on direct pixel-by-pixel validation.

Additionally, the generation of pseudo-labels imposes computational demands due to the large data volumes involved, often resulting in redundant labels or outliers, even after resampling optimizations. Although classification accuracy remained consistently high across resampling schemes, the quality of input imagery remains a critical factor, particularly with respect to cloud cover and shadow contamination. Moreover, the method exhibits limitations in distinguishing spectrally similar surface types, such as snow and superimposed ice or firn, where spectral overlap can lead to subtle misclassifications. While the clustering approach captures heterogeneous surface conditions more effectively than fully supervised methods, further methodological refinement is required to resolve these ambiguities.

From a glaciological perspective, it is important to note that while the derived ELA is strongly correlated with annual mass balance, it serves as a proxy rather than a complete indicator. This method accurately delineates the transition boundary but cannot determine the magnitude of accumulation or ablation occurring respectively above and below the ELA. Finally, the operational success of this framework is strictly reliant on the availability of high-quality, cloud-free optical imagery during the end-of-season window; persistent cloud cover remains a fundamental constraint that may necessitate the integration of SAR data for all-weather monitoring.

6.2. Optimizing Snowline Altitude Extraction

Glacier surfaces in the Arctic exhibit complex topography, including steep slopes, ridges, and variable aspects. These topographic factors dictate solar radiation loading, leading to spatially heterogeneous melt patterns (e.g., differential ablation on sun-exposed versus shaded slopes) that often confound static snowline mapping techniques [

11]. The present results demonstrate that embedding a statistical validation step into snowline extraction markedly improves accuracy by smoothing these local radiative effects. Elevation binning of snow–ice boundary pixels at 5 m intervals, followed by summary statistics, effectively reduces the influence of outliers and anomalous pixels driven by local topography.

The SPEH method alone achieves a respectable yet borderline-significant correlation with field-derived ELA (

,

) but yields a high RMSE of 231.9 m. Introducing an elevation-bin threshold at a SCR of 0.5 raises correlation to

(

) and lowers RMSE to 190.1 m (

Table 5), indicating substantial error reduction. A more stringent threshold of SCR = 0.8 yields near-perfect agreement with in situ ELA (

,

) and a substantially reduced RMSE of 30.0 m. These results indicate that elevation-bin filtering, especially at higher SCR thresholds, reliably isolates the snow–ice transition zone, even under interannual variability (2019–2023). The integration of high-fidelity classification with elevation-stratified filtering thus provides a validated framework for SLA extraction in complex Arctic terrain.

As shown in

Table 5, increasing the SCR threshold from

to

improves agreement with field-derived ELA, reducing the RMSE from 190.1 m to 30.0 m and improving the correlation from

to

. This improvement reflects a substantial reduction in the systematic negative bias associated with lower thresholds.

To quantify this effect,

Table 7 lists the year-wise residuals

(from

Table 4) for both

and

.

These residuals confirm the following:

At , SLARS persistently underestimates ELA by approximately 150–220 m, indicating a strong negative bias likely attributable to mixed-pixel effects near the snow–ice boundary.

At , residuals are smaller and more symmetrically distributed around zero (e.g., +4 m in 2019, and −14 to −53 m in other years), resulting in a mean bias of −23.4 m and RMSE of approximately 30 m.

Because SLA

RS increases monotonically with an increase in SCR thresholds, further raising the threshold (e.g., to 0.85–0.90) would likely result in overestimation of SLA

RS and increase sensitivity to classification noise due to reduced sample sizes near the snow–ice transition. Given that

already yields minimal bias and high stability, it represents an effective trade-off between bias and variance. Evidence from

Table 5 and

Table 7 supports

as a near-optimal threshold for SLA mapping at White Glacier.

6.3. Validation of SLARS Against Field-Derived ELAs

Validation of remotely sensed snowline altitude (SLA

RS) using the elevation-bin method at a SCR threshold of 0.8 against field-derived ELAs on White Glacier (2019–2023) yielded a near-perfect Pearson correlation (

,

) and a RMSE of 30.0 m (

Table 5). Such a strong relationship confirms the efficacy of high-threshold SCR binning for capturing interannual SLA variability in Arctic optical imagery and aligns with previous reports of robust SLA–ELA agreement [

7,

8,

12]. Despite the strong correlation, SLA

RS consistently underestimated field-derived ELAs by an average of 30 m in this study. This systematic bias is well documented in the literature, with typical SLA underestimations ranging from 10–30 m and RMSE values of 40–60 m [

28], while a pan-Arctic analysis found a mean SLA–ELA discrepancy of approximately −100 m [

10].

The dominant contributor to this bias is the temporal mismatch between image acquisition and the true end of the ablation season. Satellite imagery often fails to capture the glacier surface precisely at the end of the ablation season, instead recording transient snowlines during late-season accumulation or refreezing events [

8]. Even small timing differences—in the order of days to weeks—can cause SLA

RS to fall tens of metres below the in situ ELA [

10].

In addition, subpixel mixing at the snow–ice boundary further biases the mapped snowline downward. In moderate-resolution imagery, a pixel straddling snow and bare ice can be classified as snow-covered, effectively placing the snowline too far into the ablation zone (e.g., a 30 m Landsat-class pixel). Additionally, thin snow layers, superimposed ice and wet snow exhibit high reflectance in Sentinel-2 bands, promoting premature delineation of the snow–ice transition [

29,

30]. Late-season snowfall or lingering firn/superimposed-ice patches can make low elevations appear snow-covered even where net balance is near zero or negative [

7]. These effects encourage automated classifiers to map snow where bare ice had emerged, thereby lowering the derived SLA.

Topographic shading and cloud contamination introduce additional uncertainty. Shadows can obscure snow, and bright cloud or cloud-shadow artifacts may be misclassified as snow, either masking the true snowline or shifting it downward [

7,

28].

Errors in the DEM used to assign elevations to mapped snow pixels also propagate into SLA estimates. Vertical uncertainties and co-registration offsets on the order of 10–20 m can shift SLA

RS by several metres [

7]. Use of DEM mosaics (e.g., 2011–2021 composites) may introduce temporal mismatches with recent surface change, although such effects are likely random rather than systematic [

21].

Taken together, the observed mean bias of −23.4 m and overall accuracy (RMSE = 30 m) are consistent with previously reported SLA–ELA agreement Rastner et al. [

7] (±19 m) and Li et al. [

12] (±24 m), underscoring the importance of acquisition timing and surface-condition variability in SLA–ELA comparisons. In years of extreme melt or rapid topographic change, these offsets can increase substantially [

31]. Future work should prioritize tighter temporal matching to the end of ablation, contemporaneous DEMs, and the integration of spectral–angular constraints (e.g., radiative-transfer or multi-angular methods) to mitigate misclassification. Despite the noted challenges, the very high correlation and modest, interpretable bias demonstrate that Sentinel-2 imagery combined with elevation-bin statistical filtering provides a repeatable and scalable proxy for in situ ELA in data-sparse Arctic settings.

6.4. Methodological Robustness and Parameter Selection

The architecture of the classification pipeline necessitates specific parameter selection to balance statistical stability with glaciological representativeness.

Cluster Selection (k = 4): Although statistical heuristics (specifically the Elbow Method) indicated an inertia plateau near , empirical validation demonstrated that this configuration conflated distinct snow facies, often merging wet snow with ice. Conversely, increasing to introduced noise by over-segmenting coherent features, such as topographic shadows. Consequently, was identified as the optimal configuration to resolve Ground, Ice, and two spectral states of Snow without inducing artificial segmentation.

PCA Dimensionality: While PC1 dominates the variance (>) and represents broadband albedo, the retention of PC2 () was essential. This second component encodes the spectral gradient between visible and near-infrared wavelengths—a critical feature for distinguishing wet snow from clean ice that is typically lost in single-component models.

Supervised Learning and Leakage: Random Forest hyperparameters (

, max depth 10) were explicitly constrained to prevent the memorization of pixel-level noise inherent in the pseudo-labels. It is acknowledged that training the RF on K-means outputs constitutes information sharing (“leakage”) by design. Within this semi-supervised framework, the high fidelity metrics (

Table 3) confirm that the RF successfully distilled the global clustering structure into a generalized decision boundary, rather than overfitting to local artifacts.

6.5. Uncertainties and Residual Bias

Uncertainties in the derived snowline altitudes arise from a combination of atmospheric conditions, sensor resolution, and the temporal offset between satellite acquisition and glaciological events. Although cloud screening using the Sentinel-2 quality-assurance band (QA60) reduced classification errors, thin clouds and topographic shadows occasionally produce subtle misclassification [

9]. Consequently, continued development of cloud/shadow masks and the integration of multi-sensor data (e.g., synthetic aperture radar, thermal infrared) are recommended to better capture ephemeral refreezing events and resolve atmospheric artifacts.

A significant source of systematic bias lies in the temporal mismatch between the satellite image acquisition and the stratigraphic end of the ablation season. The “Minimum SCR” date derived from satellite imagery serves as a proxy for the end of the melt season but rarely coincides perfectly with the true transition. In the high Arctic, ablation often continues into late August or early September, potentially occurring after the last cloud-free optical acquisition. As a result, the satellite-derived SLA frequently captures a transient snowline that has not yet reached its maximum elevation, contributing to the observed negative bias (systematic underestimation) relative to the field-derived ELA.

Structural uncertainty is introduced by the spectral ambiguity of superimposed ice (SI) and firn layers. Koerner [

32] emphasized the influence of SI on sub-polar glacier mass balance, highlighting the difficulty of delineating the late-season snowline where refrozen meltwater obscures the transition. Similarly, Woodward et al. [

33] demonstrated that superimposed-ice formation can confound both optical and radar-derived snowline mapping. In the context of this study, SI is often spectrally indistinguishable from bare ice or wet snow depending on its surface roughness and water content. If the classifier groups SI with glacier ice rather than the accumulation zone, the derived SLA will be overestimated; conversely, if SI is classified as snow, the SLA will be underestimated. This spectral ambiguity represents a physical limitation that standard multispectral classification cannot fully resolve without ancillary data.

Spatial resolution limitations at 10 m introduce mixed-pixel effects, particularly at the snowline where pixels often contain a heterogeneous mixture of firn, bare ice, and shadow. The influence of this sub-pixel mixing is underscored by the sensitivity of the SLA to the binning threshold, where the RMSE reduced from 190 m at to 30 m at . A standard majority threshold () systematically classifies these mixed pixels as snow, artificially lowering the SLA. The necessity of the higher threshold confirms that a strict “dominant snow” criterion is required to filter out this sub-pixel noise. Additionally, the use of a static ArcticDEM mosaic (derived largely from 2011–2017 data) to extract elevations for 2019–2024 imagery introduces a vertical error component due to surface drawdown. However, field observations suggest that thinning magnitude in the accumulation zone is secondary to the timing and mixed-pixel errors described above.

Finally, a limitation of this study is the absence of independent quantitative validation at the pixel level (e.g., Kappa coefficients derived from manual digitization), which was restricted by the scarcity of contemporaneous high-resolution data. While the RF classifier demonstrates high internal consistency with the pseudo-labels (

Table 3), this does not guarantee immunity to semantic errors, such as the misclassification of firn as ice or topographic shadows as wet snow. However, the impact of these potential pixel-level errors is mitigated by the aggregation strategy used to derive the SLA. The elevation binning method (

) effectively acts as a spatial filter, requiring a consistent snow cover fraction across the glacier width to define the snowline. The strong correlation with independent field-derived ELA (

) suggests that while pixel-level noise may exist, the aggregate snowline determination remains robust and physically representative.

6.6. Applicability to Complex Glacier Terrain

While the proposed workflow demonstrates high efficacy for White Glacier, it is important to contextualize this success within the glacier’s morphology. White Glacier is a predominantly clean-ice system with high spectral contrast between the glacier surface and the surrounding bedrock. For debris-covered glaciers or those with complex topography, the current feature space (Sentinel-2 bands) may be insufficient to distinguish supraglacial debris from periglacial terrain. To transfer this semi-supervised approach to such environments, specific adaptations are recommended:

Spectral Expansion: Incorporating Shortwave Infrared (SWIR) bands (e.g., Sentinel-2 B11/B12) and thermal data (e.g., Landsat TIRS) would enhance the discrimination between debris-covered ice and bedrock based on mineral composition and surface temperature.

Topographic Features: Integrating DEM derivatives, such as slope, aspect, and illumination corrections, into the feature vector could reduce misclassification in deeply shadowed accumulation zones.

Texture Analysis: Utilizing texture metrics (e.g., Grey Level Co-occurrence Matrix) may help resolve the morphological differences between hummocky debris tongues and stable ground, which spectral data alone cannot capture.

6.7. Future Research Directions in SLA and SCR Detection

To enhance the quality of the raw dataset for clustering, future research should focus on integrating multi-sensor datasets, such as Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and thermal imagery, to complement optical data and improve the detection of surface meltwater, refreezing events, and superimposed ice layers. Nambiar et al. [

15] showcased the effectiveness of a self-trained model for cloud, shadow, and snow detection in Sentinel-2 imagery of snow- and ice-covered regions, highlighting the transformative potential of automated frameworks in mitigating classification challenges. These methodologies can address persistent issues with cloud cover and shadow variability in complex, glaciated terrain. Furthermore, leveraging High-Spectral-Dimensional Neighborhood Search (HSDNS) could enhance pseudo-label creation by extracting intricate feature similarities in raw datasets, thus increasing classification accuracy and reliability.

Furthermore, while this study demonstrated the utility of a static high-confidence threshold (), future iterations of the workflow will implement an automated parameter sweep (e.g., testing SCR thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95). This would allow for dynamic threshold optimization based on scene-specific conditions, potentially minimizing the residual SLA–ELA offset.

Transitioning from static classifiers to time-resolved machine learning approaches, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs), would support explicit tracking of melt progression and refine end-of-season snowline altitude estimates. Incorporating contemporaneous elevation data from ongoing ArcticDEM updates and/or unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) surveys would reduce uncertainties associated with temporal DEM–surface mismatches. Automating the processing pipeline on scalable cloud platforms would enable near-real-time analysis of large image time series. Finally, coupling derived snowline altitudes with ELA gradients offers a pathway to infer glacier mass balance at individual and regional scales, improving the utility of the approach for Arctic cryospheric monitoring.

7. Conclusions

This study developed a hybrid machine learning framework to monitor glacier surface variables, specifically estimating SCR and SLA on White Glacier, Canadian high Arctic. The methodology combines unsupervised K-means clustering for pseudo-label generation with supervised classification using a RF algorithm, addressing limitations associated with traditional field-based monitoring in remote Arctic environments.

Satellite-derived SLAs were strongly correlated with field-derived ELAs (r = 0.99), demonstrating the potential of optical remote sensing for proxy mass balance estimation. A systematic offset between SLA and ELA was identified, indicating the need for further refinement in spectral discrimination and temporal alignment between remote sensing observations and in situ measurements.

Key contributions of this study include the following:

Automated Label Generation via Spectral Clustering: A semi-supervised classification pipeline was established wherein a Random Forest classifier reproduced unsupervised spectral clustering with >99% fidelity. This approach effectively circumvents the bottleneck of manual annotation in data-sparse regions while preserving critical spectral variance through PCA dimensionality reduction.

Operational Integration and Physical Validation: This study demonstrates that optical pseudo-labels can be converted into physically meaningful mass balance proxies (SLA) when constrained by high-threshold elevation binning (). Validation against the long-term in situ record of White Glacier confirmed a strong agreement (), establishing the workflow as a viable proxy for equilibrium line monitoring.

Characterization of Interannual Variability: The derived time series (2019–2024) effectively captured the glacier’s interannual response to climatic forcing, resolving distinct ablation regimes such as the suppressed melt of 2021 versus the intense ablation of 2023. These trends provide observational constraints for regional mass balance assessments.

Uncertainty Benchmarking: A systematic assessment of errors identified acquisition timing and mixed-pixel effects as dominant sources of bias. The quantification of the residual SLA–ELA offset (≈−30 m) provides a calibrated benchmark for transferring this methodology to unmonitored basins.

Limitations of the current framework include spectral ambiguity in superimposed ice zones, residual cloud contamination, and vertical errors associated with the static digital elevation model. Future research should prioritize the integration of multi-sensor datasets (e.g., SWIR, SAR) to resolve complex surface facies and the application of temporally resolved classification models. Furthermore, synchronizing contemporaneous elevation data with optical acquisitions is recommended to minimize geometric mismatches in rapidly thinning ablation zones.

This study demonstrates the applicability of remote sensing and machine learning for monitoring clean-ice glaciers in data-sparse polar regions. The framework offers a scalable tool for tracking glacier change in clean-ice Arctic environments and contributes to broader efforts to understand and model cryospheric responses to climate forcing. Future research should focus on improving classification accuracy, increasing temporal resolution, and integrating multi-source datasets to support glaciological analysis and climate policy development.