3D High-Resolution Seismic Imaging of Elusive Seismogenic Faults: The Pantano-Ripa Rossa Fault, Southern Italy

Highlights

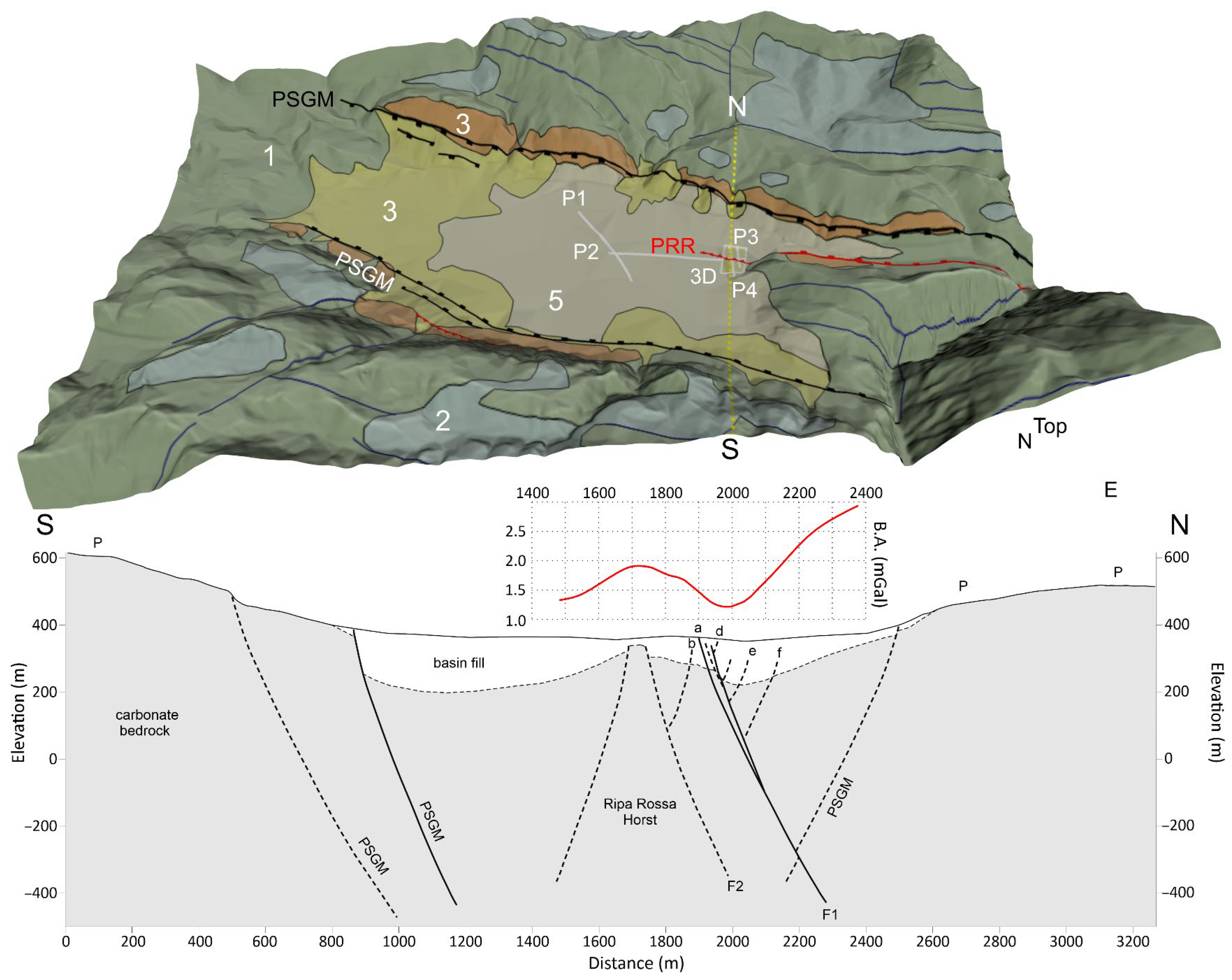

- First application of high-resolution 3D seismic imaging to a seismogenic fault in a complex intramontane basin, providing the first detailed subsurface images of a branch of the causative fault of the 1980 Mw 6.9 Irpinia Earthquake and associated depocenter.

- Integration of new 3D data with 2D legacy profiles demonstrates that 3D seismic surveys significantly outperform 2D methods in imaging subtle, shallow faults, capturing fault splays, stratigraphy, and basement depth variations unresolved by 2D approaches.

- The results show that 2D imaging alone can lead to depth inaccuracies, misinterpretations, and incomplete estimates of fault displacement in structurally complex basins, while 3D seismic data provide a robust basis for assessing fault geometry and basin evolution.

- High-resolution 3D imaging opens new opportunities for paleoseismic calibration and drilling, offering optimal targets to constrain slip rates, timing of fault activity, and basin stratigraphy—critical steps toward improving seismic hazard assessment in active intramontane systems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Settings

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Two-Dimensional Seismic Surveys

3.2. Three-Dimensional Seismic Survey

3.3. Data Processing

4. Seismic Interpretation

4.1. Seismo-Stratigraphic Features

4.2. Structural Features

4.3. The 3D Volume

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRR | Pantano Ripa-Rossa |

| PSGM | Pantano-San Gregorio Magno |

| NMO | Normal MoveOut |

| CMP | Common MidPoint |

| VMB | Velocity model-building |

| RMO | Residual Move-Out |

| PSDM | Pre-Stack Depth Migration |

References

- Collettini, C.; Chiaraluce, L.; Pucci, S.; Barchi, M.R.; Cocco, M. Looking at fault reactivation matching structural geology and seismological data. J. Struct. Geol. 2005, 27, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valoroso, L.; Chiaraluce, L.; Piccinini, D.; Di Stefano, R.; Schaff, D.; Waldhauser, F. Radiography of a normal fault system by 64,000 high-precision earthquake locations: The 2009 L’Aquila (central Italy) case study. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 1156–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civico, R.; Pucci, S.; Villani, F.; Pizzimenti, L.; De Martini, P.M.; Nappi, R.; Open EMERGEO Working Group. Surface ruptures following the 30 October 2016 Mw 6.5 Norcia earthquake, central Italy. J. Maps 2018, 14, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, F.; Pucci, S.; Civico, R.; De Martini, P.M.; Cinti, F.R.; Pantosti, D. Surface Faulting of the 30 October 2016 Mw 6.5 Central Italy Earthquake: Detailed Analysis of a Complex Coseismic Rupture. Tectonics 2018, 37, 3378–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzi, F.; Roberts, G.; Walker, J.F.; Papanikolaou, I. Occurrence of partial and total coseismic ruptures of segmented normal fault systems: Insights from the Central Apennines, Italy. J. Struct. Geol. 2019, 126, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure Walker, J.; Boncio, P.; Pace, B.; Roberts, G.; Benedetti, L.; Scotti, O.; Visini, F.; Peruzza, L. Fault2SHA Central Apennines database and structuring active fault data for seismic hazard assessment. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, S.; Lavecchia, G.; Andrenacci, C.; Ercoli, M.; Cirillo, D.; Carboni, F.; Barchi, M.R.; Brozzetti, F. Complex trans-ridge normal faults controlling large earthquakes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantosti, D.; Valensise, G. Faulting mechanism and complexity of the November 23, 1980, Campania-Lucania earthquake, inferred from surface observations. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, R.; Jackson, J. The earthquake of 1980 november 23 in campania-basilicata (southern Italy). Geophys. J. Roy. Astron. Soc. 1987, 90, 375–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Zollo, A. The Irpinia (Italy) 1980 earthquake: Detailed analysis of a complex normal faulting. J. Geophys. Res. 1989, 94, 1631–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardini, D. Teleseismic observation of the November 23 1980, Irpinia earthquake. Ann. Geophys. 1993, 36, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, S.; de Nardis, R.; Scarpa, R.; Brozzetti, F.; Cirillo, D.; Ferrarini, F.; di Lieto, B.; Arrowsmith, R.J.; Lavecchia, G. Fault pattern and seismotectonic style of the Campania–Lucania 1980 earthquake (Mw 6.9, Southern Italy): New multidisciplinary constraints. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 8, 608063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, A.; Nardò, S.; Mazzoli, S. The MS 6.9, 1980 Irpinia Earthquake from the Basement to the Surface: A Review of Tectonic Geomorphology and Geophysical Constraints, and New Data on Postseismic Deformation. Geosciences 2020, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, R.; Jackson, J. Surface faulting in the southern Italian Campania-Basilicata earthquake of 23 November 1980. Nature 1984, 312, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, A.; Cinque, A.; Improta, L.; Villani, F. Late Quaternary faulting within the Southern Apennines seismic belt: New data from Mt. Marzano area (Southern Italy). Quat. Int. 2003, 101–102, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improta, L.; Zollo, A.; Bruno, P.P.; Herrero, A.; Villani, F. High-resolution seismic tomography across the 1980 (Ms 6.9) Southern Italy earthquake fault scarp. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, P.A.C.; Giocoli, A.; Peronace, E.; Piscitelli, S.; Quadrio, B.; Bellanova, J. Integrated near surface geophysics across the active Mount Marzano Fault System (southern Italy): Seismogenic hints. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2014, 103, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, P.; Peronace, E. New paleoseismic data from the Irpinia Fault. A different seismogenic perspective for southern Apennines (Italy). Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 136, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriozzi, F.; Improta, L.; Maesano, F.E.; De Gori, P.; Basili, R. The 3D crustal structure in the epicentral region of the 1980, Mw 6.9, Southern Apennines earthquake (southern Italy): New constraints from the integration of seismic exploration data, deep wells, and local earthquake tomography. Tectonics 2024, 43, e2023TC008056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.; Spann, M.; Turner, J.; Wright, T. Fault surface detection in 3-D seismic data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hale, D. 3D seismic image processing for faults. Geophysics 2016, 81, IM1–IM11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopini, D.; Butler, R.W.H.; Purves, S.; McArdle, N.; De Freslon, N. Exploring the seismic expression of fault zones in 3D seismic volumes. J. Struct. Geol. 2016, 89, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.S. Definition of subsurface stratigraphy, structure and rock properties from 3-D seismic data. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1999, 47, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.; Huuse, M. 3D seismic technology: The geological ‘Hubble’. Basin Res. 2005, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.; Holden, C.; Beavan, J.; Beetham, D.; Benites, R.; Celentano, A.; Zhao, J. The Mw 6.2 Christchurch earthquake of February 2011: Preliminary report. N. Z. J. Geol. Geophys. 2012, 55, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, P.P.G.; Ferrara, G.; Zambrano, M.; Maraio, S.; Improta, L.; Volatili, T.; Di Fiore, V.; Florio, G.; Iacopini, D.; Accomando, F.; et al. Multidisciplinary High Resolution Geophysical Imaging of Pantano Ripa Rossa Segment of the Irpinia Fault (Southern Italy). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquini, S.; Isola, I.; Favalli, M.; Battistini, A.; Dotta, G. TINITALY, a Digital Elevation Model of Italy with a 10 Meters Cell Size (Version 1.1) [Dataset]. Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). 2023. Available online: https://tinitaly.pi.ingv.it/Download_Area1_1.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Pondrelli, S.; Salimbeni, S. Italian CMT Dataset [Data Set]; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV): Roma, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Ascione, A.; Barra, D.; Munno, R.; Petrosino, P.; Russo Ermolli, E.; Villani, F. Evolution of the late Quaternary San Gregorio Magno tectono-karstic basin (southern Italy) inferred from geomorphological, tephrostratigraphical and palaeoecological analyses: Tectonic implications. J. Quat. Sci. 2007, 22, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, P.P.; Castiello, A.; Improta, L. Ultrashallow seismic imaging of the causative fault of 1980, M6. 9, southern Italy earthquake by pre-stack depth migration of dense wide-aperture data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L19302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addezio, G.; Pantosti, D.; Valensise, G. Paleoearthquakes along the Irpinia fault at the Pantano di San Gregorio Magno (southern Italy). Il Quat. 1991, 4, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hippolyte, J.C.; Angelier, J.; Roure, F.B. A major geodynamic change revealed by Quaternary stress patterns in the Southern Apennines (Italy). Tectonophysics 1994, 230, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Montone, P. Present-day stress field and active tectonics in southern peninsular Italy. Geophys. J. Int. 1997, 130, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazzo, C.; Ascione, A.; Cinque, A. Late Tertiary–Quaternary tectonics of the Southern Apennines (Italy): New evidences from the Tyrrhenian slope. Tectonophysics 2006, 421, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarcia, S.; Mazzoli, S.; Vitale, S.; Zattin, M. On the tectonic evolution of the Ligurian accretionary complex in southern Italy. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2012, 124, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, A.; Mazzoli, S.; Petrosino, P.; Valente, E. A decoupled kinematic model for active normal faults: Insights from the 1980, MS = 6.9 Irpinia earthquake, southern Italy. GSA Bull. 2013, 125, 1239–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantosti, D.; D’Addezio, G.; Cinti, F.R. Paleoseismological evidence of repeated large earthquakes along the 1980 Irpinia earthquake fault. Ann. Geophys. 1993, 36, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, P. Nearly Simultaneous Pairs and Triplets of Historical Destructive Earthquakes with Distant Epicenters in the Italian Apennines. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2024, 95, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.J.; Waldhauser, F.; Ellsworth, W.L.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, W.; Michele, M.; Chiaraluce, L.; Beroza, G.C.; Segou, M. Machine-Learning-Based High-Resolution Earthquake Catalog Reveals How Complex Fault Structures Were Activated during the 2016–2017 Central Italy Sequence. Seism. Rec. 2021, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrullo, E.; De Matteis, R.; Satriano, C.; Amoroso, O.; Zollo, A. An improved 1-D seismic velocity model for seismological studies in the Campania–Lucania region (Southern Italy). Geophys. J. Int. 2013, 195, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, V.K.; Holden, H.D. Deconvolution of seismic data-an overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Electron. 1978, 16, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taner, M.T.; Koehler, F. Velocity spectra—Digital computer derivation applications of velocity functions. Geophysics 1969, 34, 859–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.A. Surface-consistent deconvolution. Geophysics 1989, 54, 1082–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hileman, J.A.; Embree, P.; Pflueger, J.C. Automated static corrections. Geophys. Prospect. 1968, 16, 326–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D. The Generalized Reciprocal Method of Seismic Refraction Interpretation; Society of Exploration Geophvsicists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Neidell, N.S.; Taner, M.T. Semblance and other coherency measures for multichannel data. Geophysics 1971, 36, 467–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, J.; Claerbout, J.F. Surface-consistent residual statics estimation by stack-power maximization. Geophysics 1985, 50, 2297–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, R.E.; Geldart, L.P. Exploration Seismology; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.H.; Etgen, J.; Dellinger, J.; Whitmore, D. Seismic migration problems and solutions. Geophysics 2001, 66, 1340–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondurur, D. Acquisition and Processing of Marine Seismic Data; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; p. 606. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.R.; Newton, A.M.W.; Huuse, M. An introduction to seismic reflection data: Acquisition, processing and interpretation. In Regional Geology and Tectonics: Principles of Geologic Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 571–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improta, L.; Zollo, A.; Herrero, A.; Frattini, R.; Virieux, J.; Dell’Aversana, P. Seismic imaging of complex structures by non-linear traveltime inversion of dense wide-angle data: Application to a thrust belt. Geophys. J. Int. 2002, 151, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutter, W.J.; Nowack, R.L. Inversion of crustal structure using reflections from the PASSCAL Ouachita Experiment. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 4633–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, A.; Zollo, A.; Virieux, J. Two-dimensional non linear first-arrival time inversion applied to Mt. Vesuvius active seismic data (TomoVes96). In 24th General Assembly, Abstract Book; European Geophysical Society: Hague, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic data analysis: Processing, inversion, and interpretation of seismic data. In Society of Exploration Geophysicists; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Biondi, B.L. 3D Seismic Imaging. Investig. Geophys. Ser. 2006, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deregowski, S.M. Prestack depth migration by the 2-D boundary integral method. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 1985; SEG: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1985; pp. 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deregowski, S.M. Common-offset migrations and velocity analysis. First Break. 1990, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Fagin, S. Becoming effective velocity-model builders and depth imagers, Part 1 and 2—The basics of prestack depth migration. Lead Edge 2002, 21, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.H.; Liberty, L.M.; Lyle, M.W.; Clement, W.P.; Hess, S. Imaging complex structure in shallow seismic-reflection data using pre stack depth migration. Geophysics 2006, 71, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stork, C. Making Depth Migration Work in Complex Structures. In Advance Geophysics; SEG: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, A.; Di Giuseppe, M.G.; Petrillo, Z.; Patella, D. Imaging 2D structures by the CSAMT method: Application to the Pantano di S. Gregorio Magno faulted basin (Southern Italy). J. Geophys. Eng. 2009, 6, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsayer, G.R. Seismic Stratigraphy, a Fundamental Exploration Tool. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 30 April–3 May 1979. OTC-3568-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembo, I. Stratigraphic architecture and quaternary evolution of the Val d’Agri intermontane basin (Southern Apennines, Italy). Sediment. Geol. 2010, 223, 206–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patruno, S.; Scisciani, V. Testing normal fault growth models by seismic stratigraphic architecture: The case of the Pliocene-Quaternary Fucino Basin (Central Apennines, Italy). Basin Res. 2021, 33, 2118–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercoli, M.; Carboni, F.; Akimbekova, A.; Carbonell, R.B.; Barchi, M.R. Evidencing subtle faults in deep seismic reflection profiles: Data pre-conditioning and seismic attribute analysis of the legacy CROP-04 profile. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1119554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, L.; Carboni, F.; Akimbekova, A.; Ercoli, M.; Bello, S.; Brozzetti, F.; Bacchiani, A.; Toscani, G. Structural architecture and tectonic evolution of the Campania-Lucania arc (Southern Apennines, Italy): Constraints from seismic reflection profiles, well data and structural-geologic analysis. Tectonophysics 2024, 879, 230313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchi, M.R.; Carboni, F.; Michele, M.; Ercoli, M.; Giorgetti, C.; Porreca, M.; Chiaraluce, L. The influence of subsurface geology on the distribution of earthquakes during the 2016–2017 Central Italy seismic sequence. Tectonophysics 2021, 807, 228797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldhauser, F.; Michele, M.; Chiaraluce, L.; Di Stefano, R.; Schaff, D.P. Fault planes, fault zone structure and detachment fragmentation resolved with high-precision aftershock locations of the 2016–2017 central Italy sequence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL092918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malz, A.; Madritsch, H.; Kley, J. Improving 2D seismic interpretation in challenging settings by integration of restoration techniques: A case study from the Jura fold-and-thrust belt (Switzerland). Interpretation 2015, 3, SAA37–SAA58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, D.C.; Backus, M.M. Offset-dependent mis-tie analysis at seismic line intersections. Geophysics 1989, 54, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruno, P.P.G.; Ferrara, G.; Improta, L.; Maraio, S. 3D High-Resolution Seismic Imaging of Elusive Seismogenic Faults: The Pantano-Ripa Rossa Fault, Southern Italy. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3717. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223717

Bruno PPG, Ferrara G, Improta L, Maraio S. 3D High-Resolution Seismic Imaging of Elusive Seismogenic Faults: The Pantano-Ripa Rossa Fault, Southern Italy. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(22):3717. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223717

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruno, Pier Paolo G., Giuseppe Ferrara, Luigi Improta, and Stefano Maraio. 2025. "3D High-Resolution Seismic Imaging of Elusive Seismogenic Faults: The Pantano-Ripa Rossa Fault, Southern Italy" Remote Sensing 17, no. 22: 3717. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223717

APA StyleBruno, P. P. G., Ferrara, G., Improta, L., & Maraio, S. (2025). 3D High-Resolution Seismic Imaging of Elusive Seismogenic Faults: The Pantano-Ripa Rossa Fault, Southern Italy. Remote Sensing, 17(22), 3717. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223717