Phase Shift Analysis of Cryosat-2 SARin Waveforms: Inland Water Off-Pointing Corrections

Highlights

- SARin data can be used to derive the roll-angle from oceanic passes and the off-pointing angle of cross-track water reflectors.

- Estimation of offset-angle enables correction for GDR altimetric height and location of inland water reflectors.

- Correction for cross track reflectors yields additional height data for inland water studies.

- Even for inland water identifiable at nadir, off-pointing considerations can improve the water height estimation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

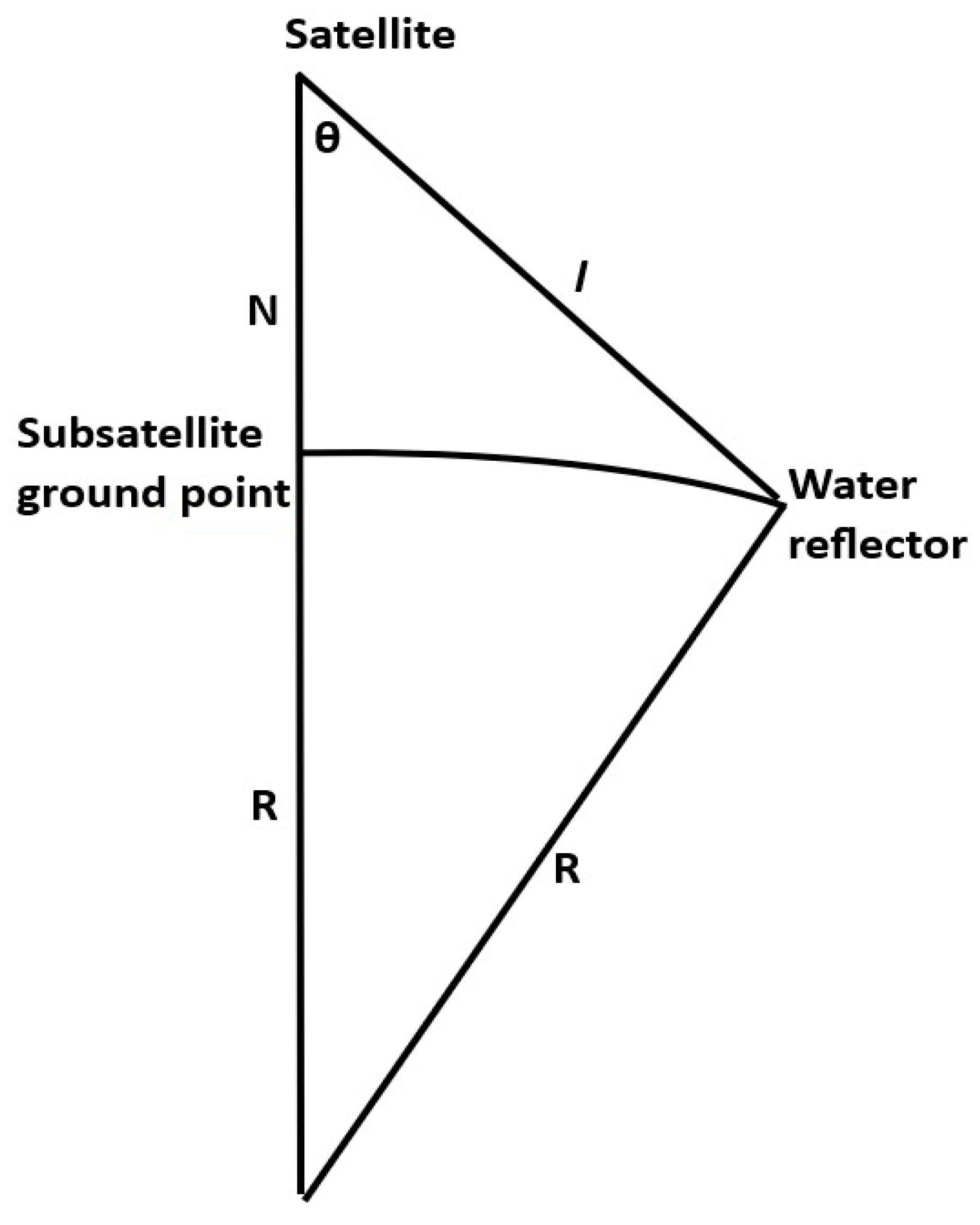

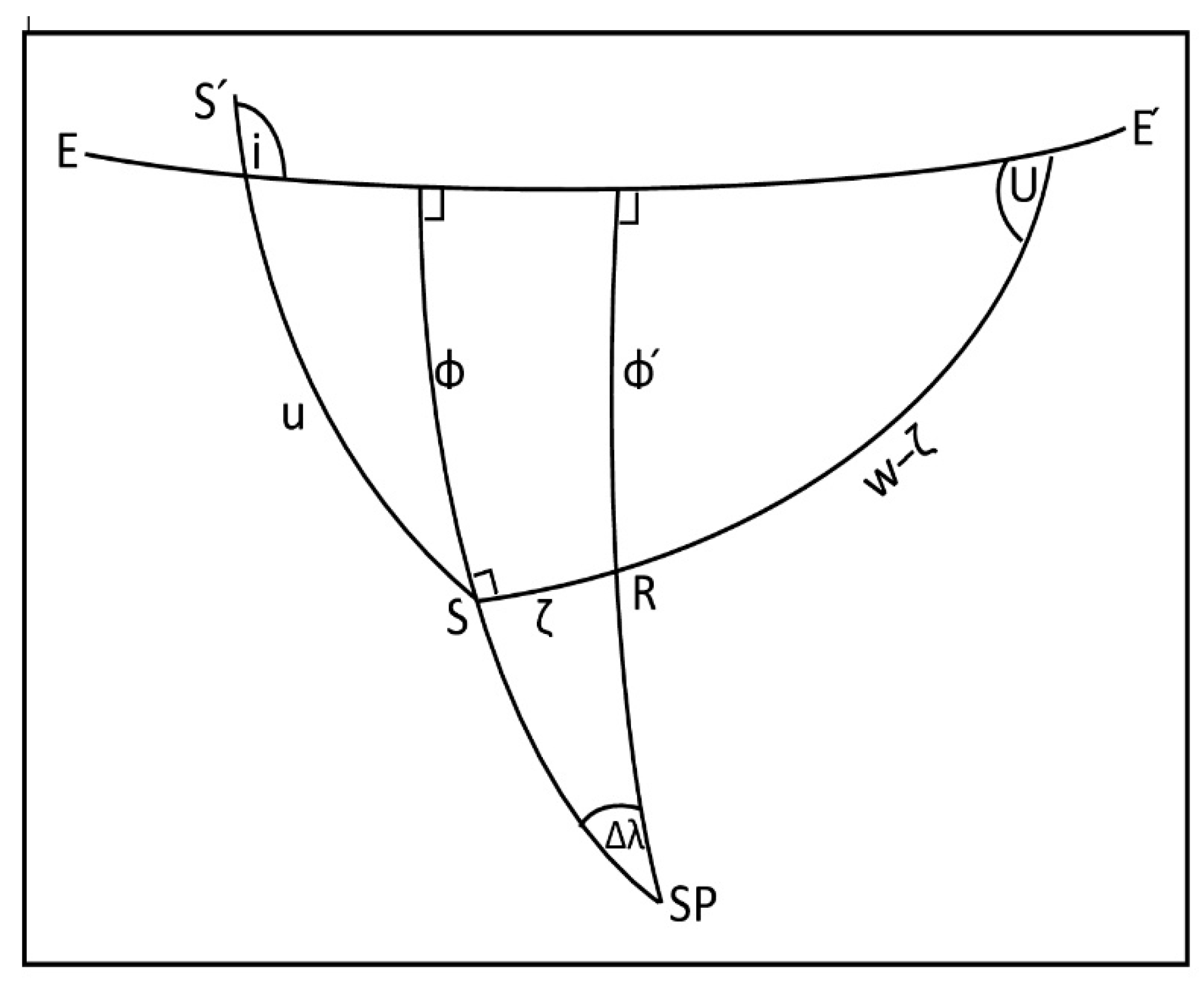

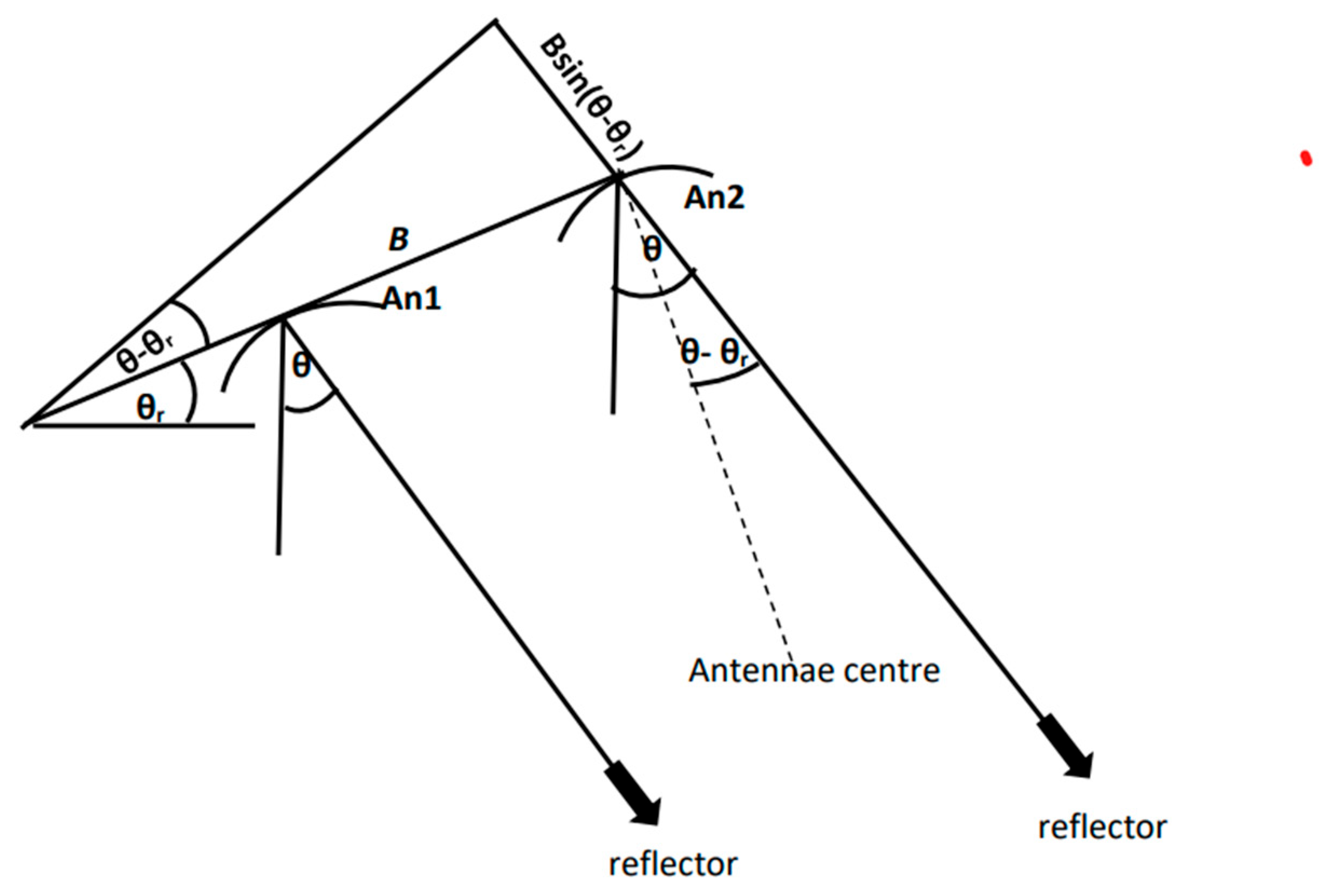

2. Cryosat-2 SARin Phase: Theory

2.1. Cryosat-2 SAR and SARin Modes

2.2. Cryosat-2 SARin Cross-Angle

- (i)

- The reflective surface is symmetrically homogeneous, ;

- (ii)

- The reflection is dominant on the + side, ;

- (iii)

- The reflection is dominant on the − side, .

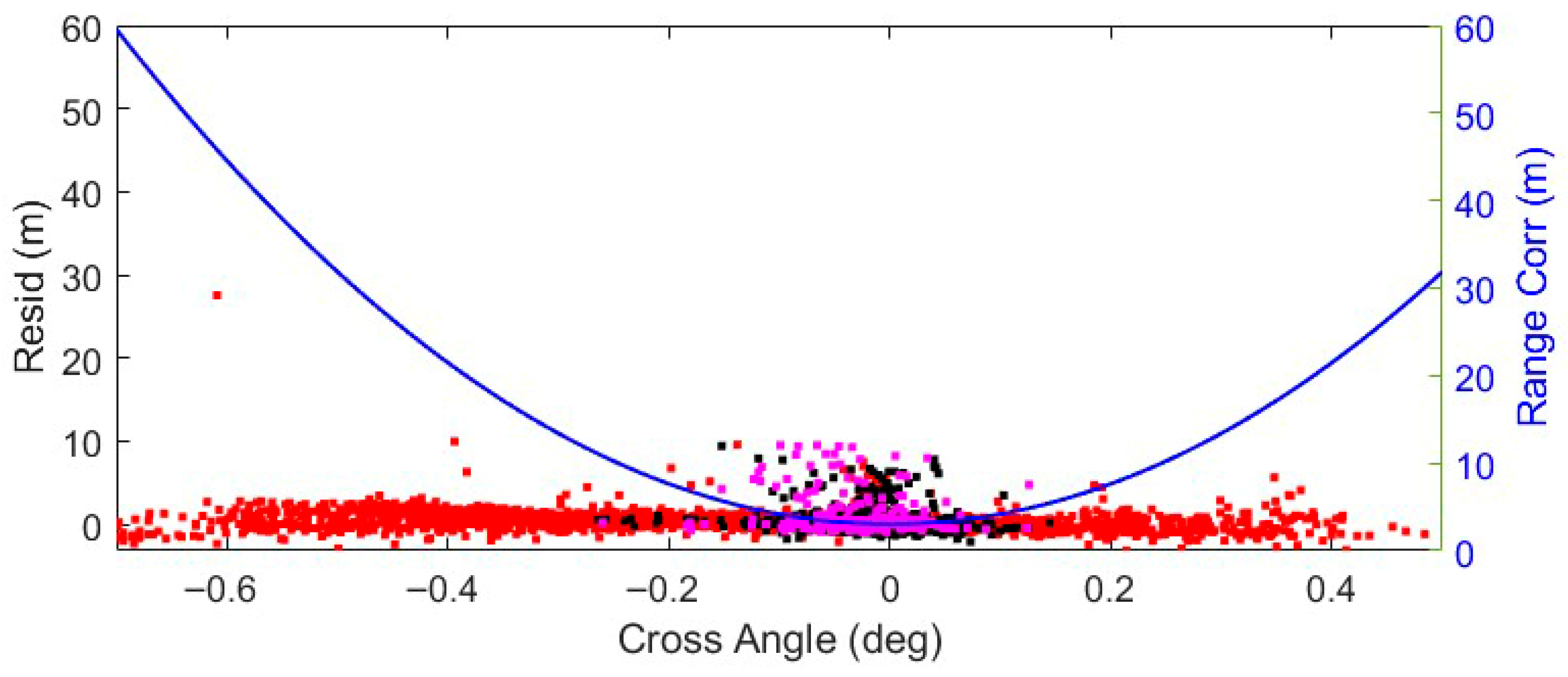

2.3. Altimetric Corrections for Non-Zero Cross-Angle

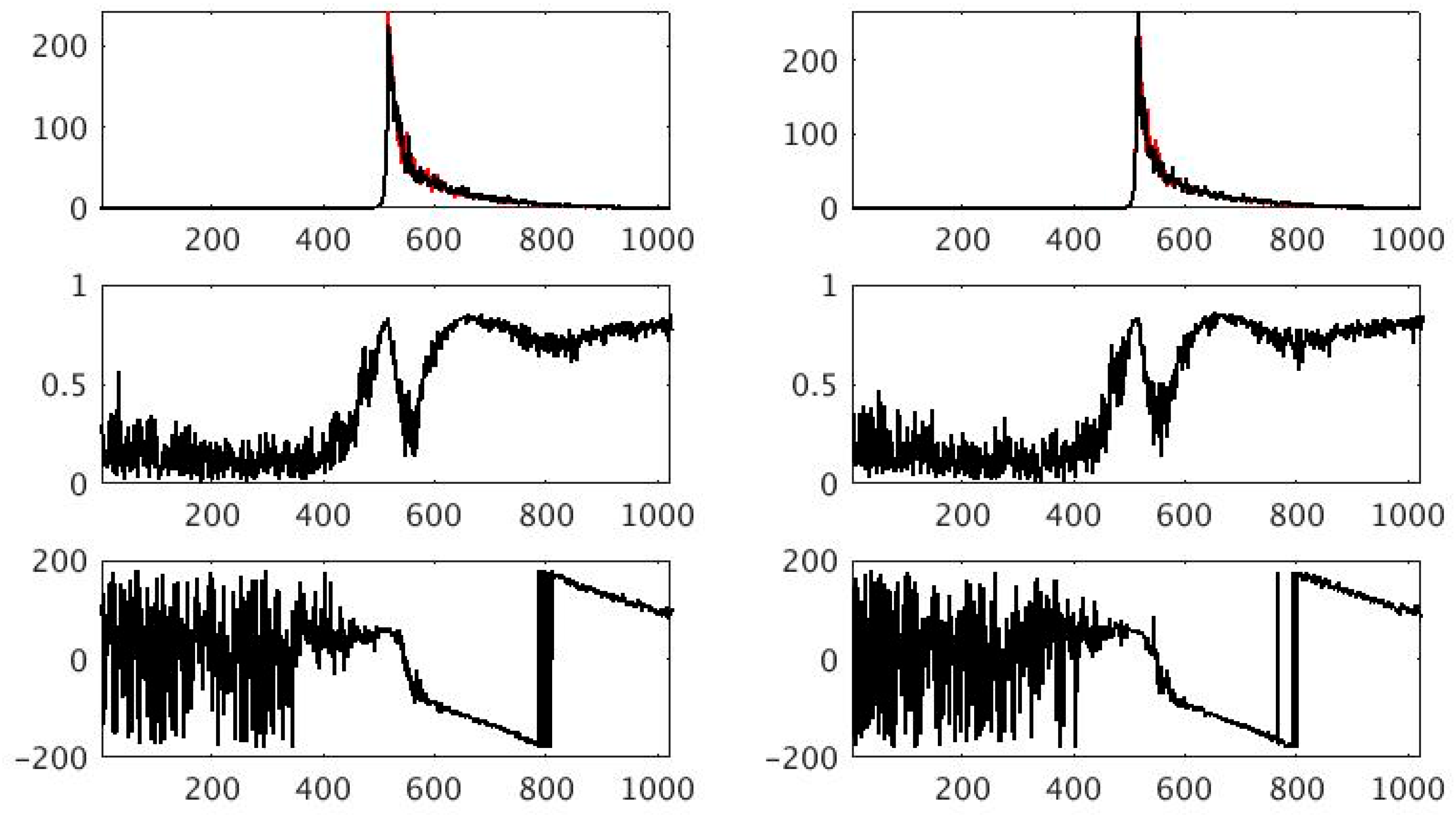

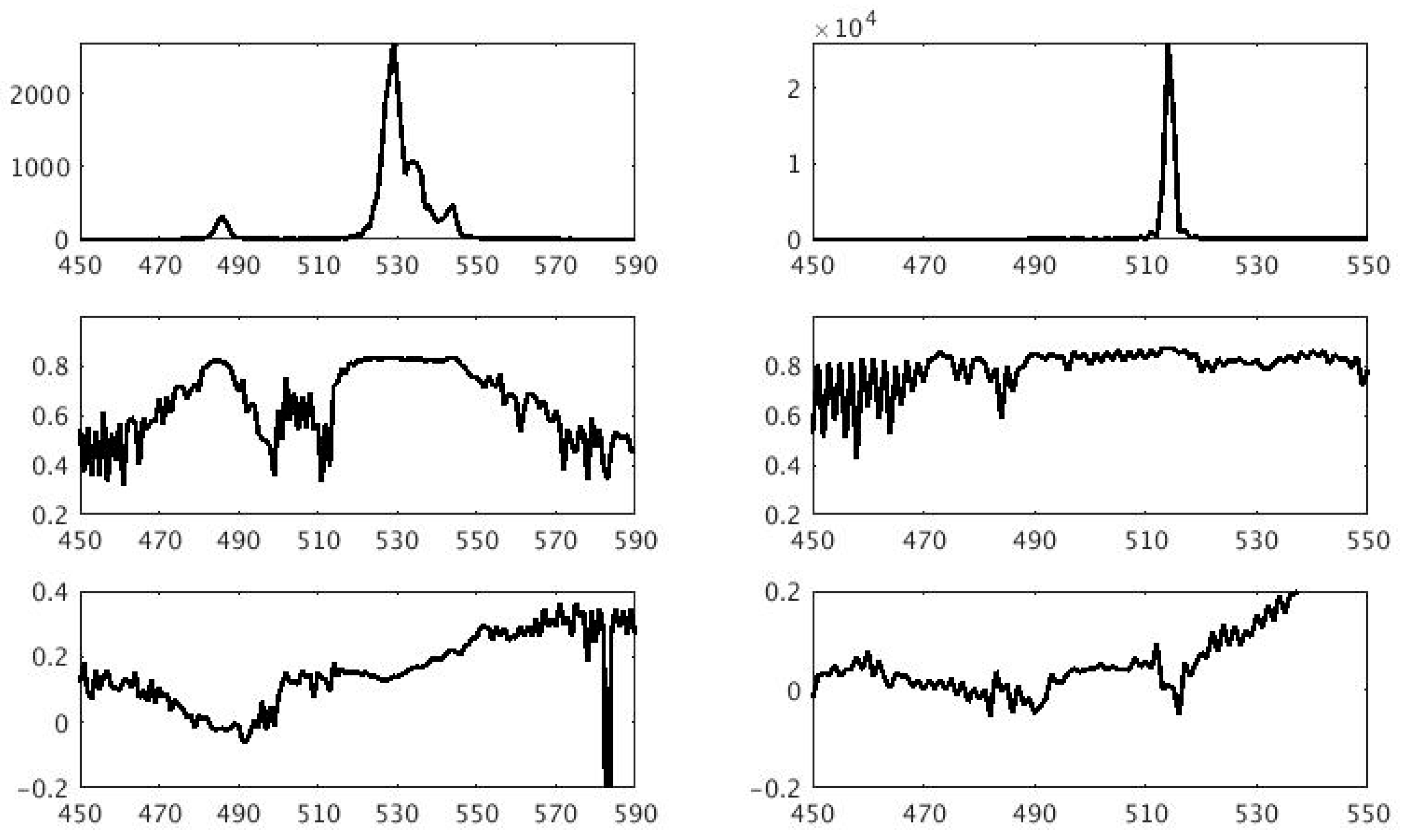

3. SARin Phase Analyses

3.1. SARin Cross-Angle over Ocean

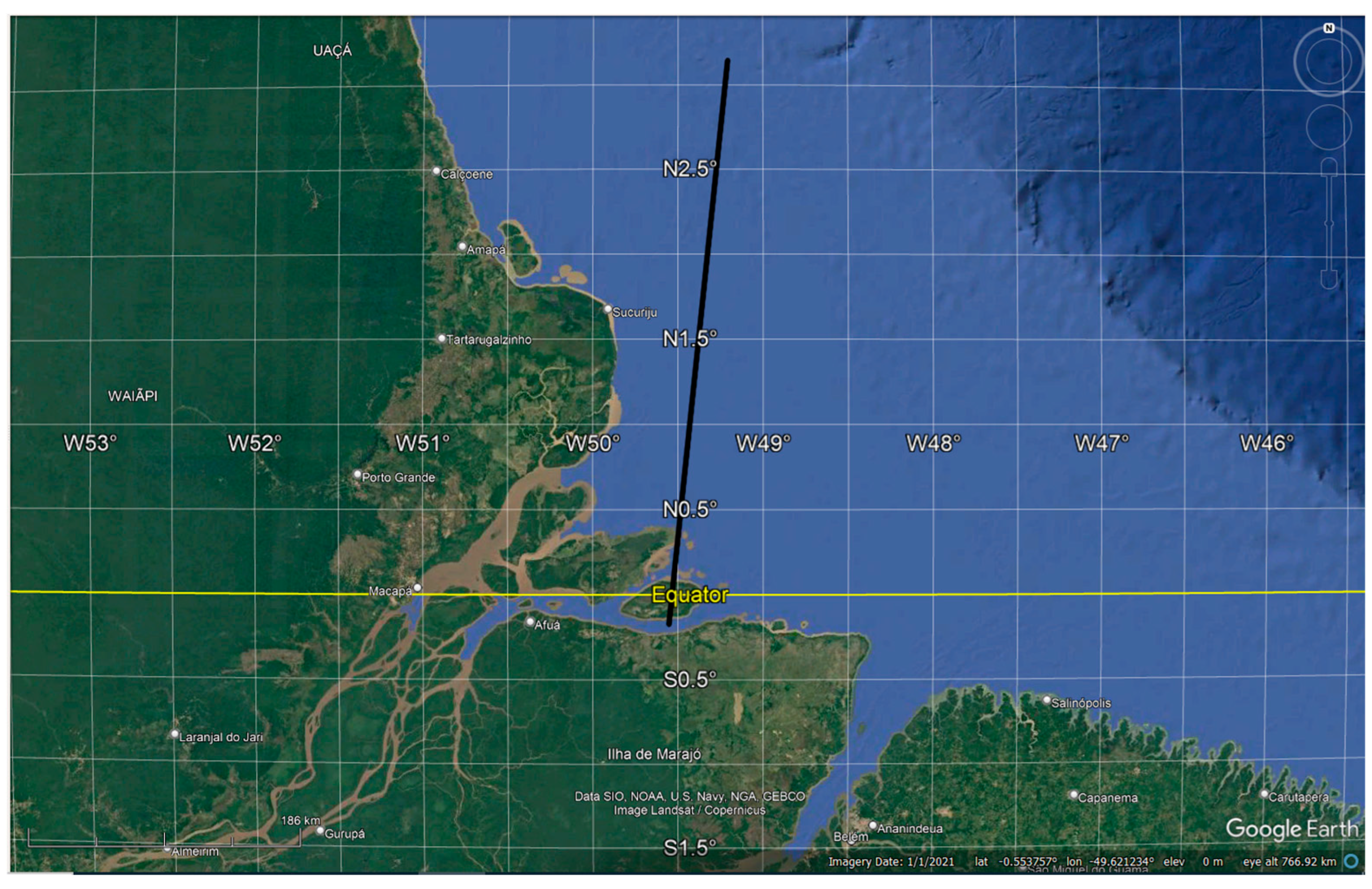

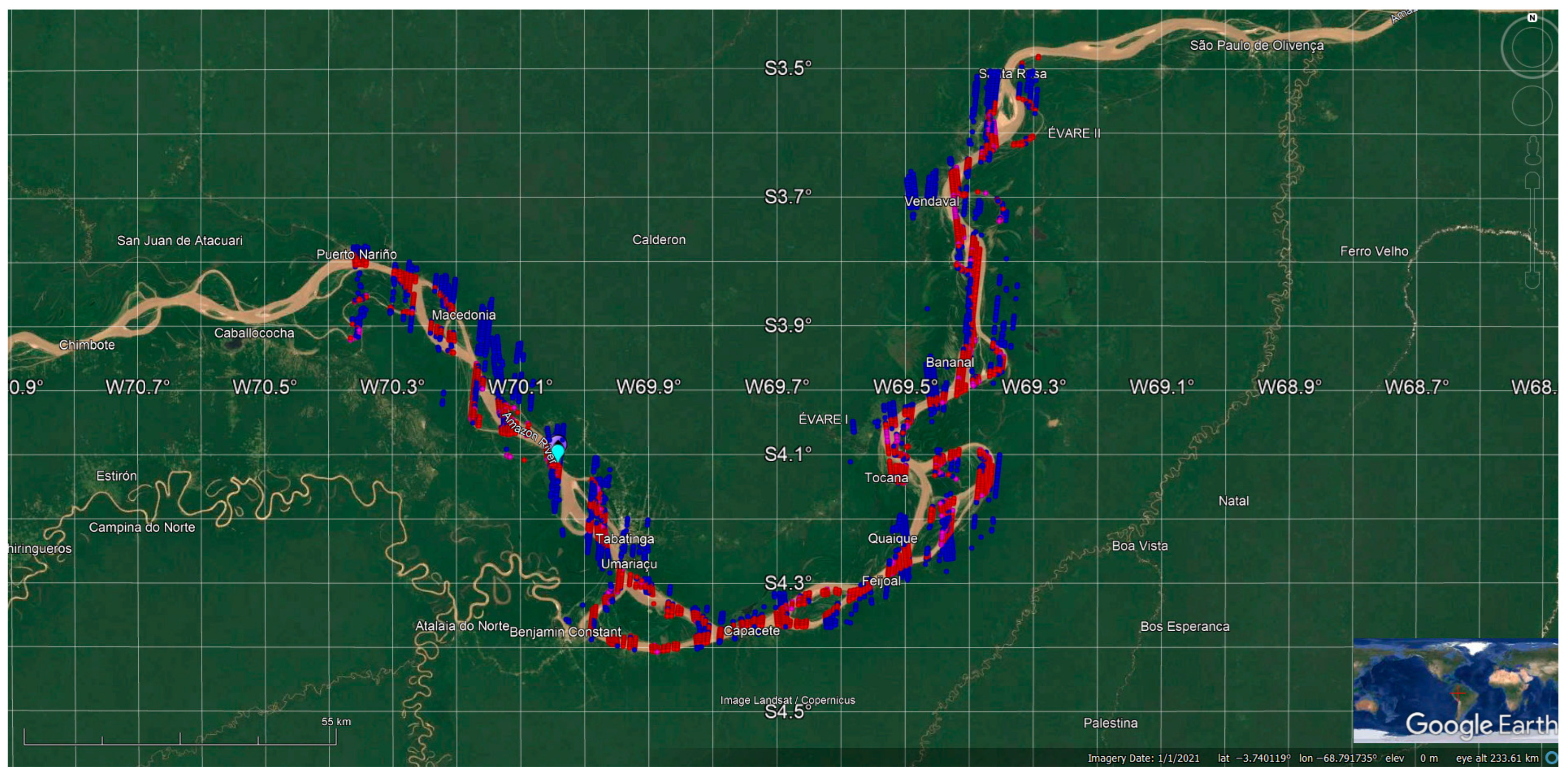

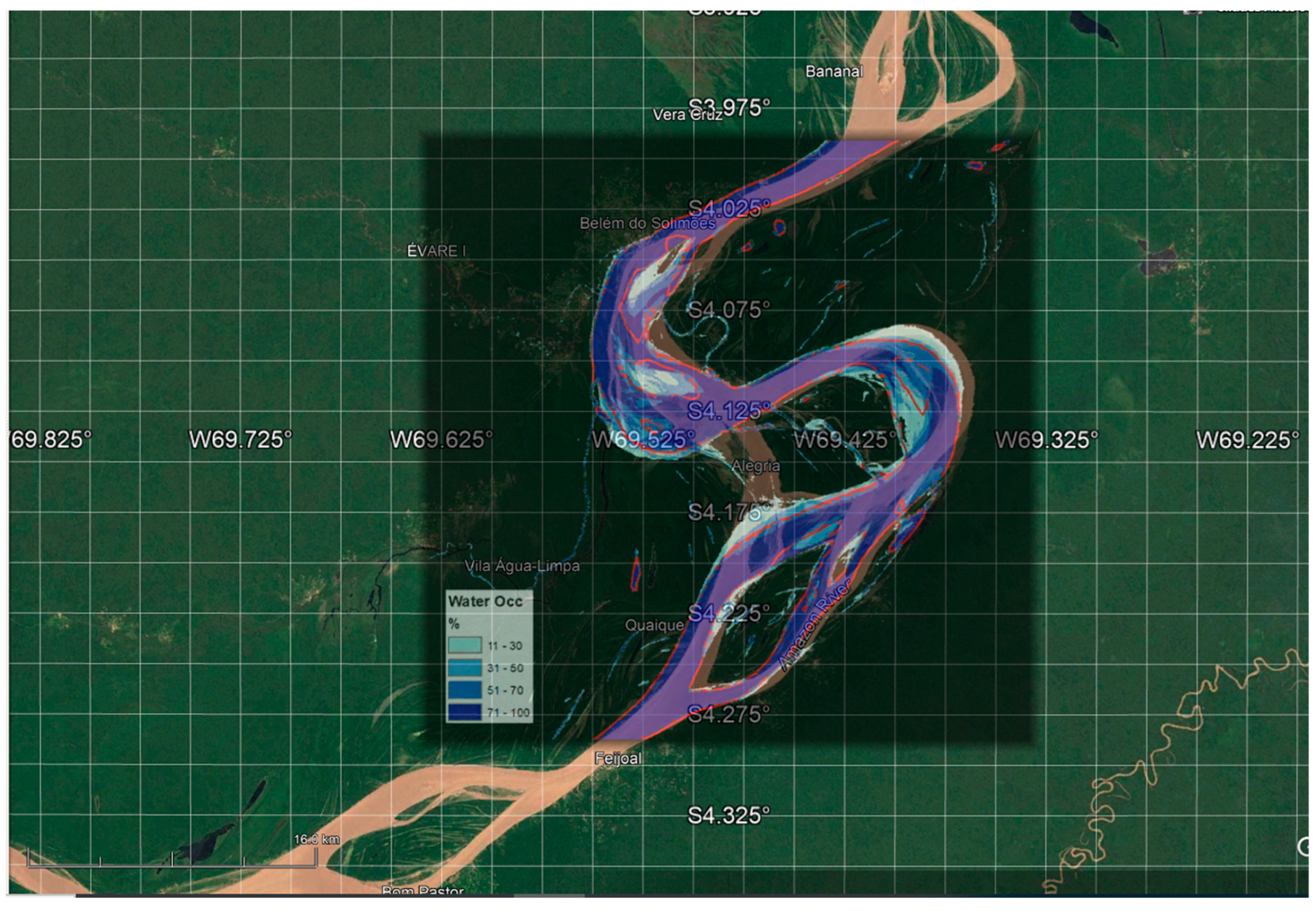

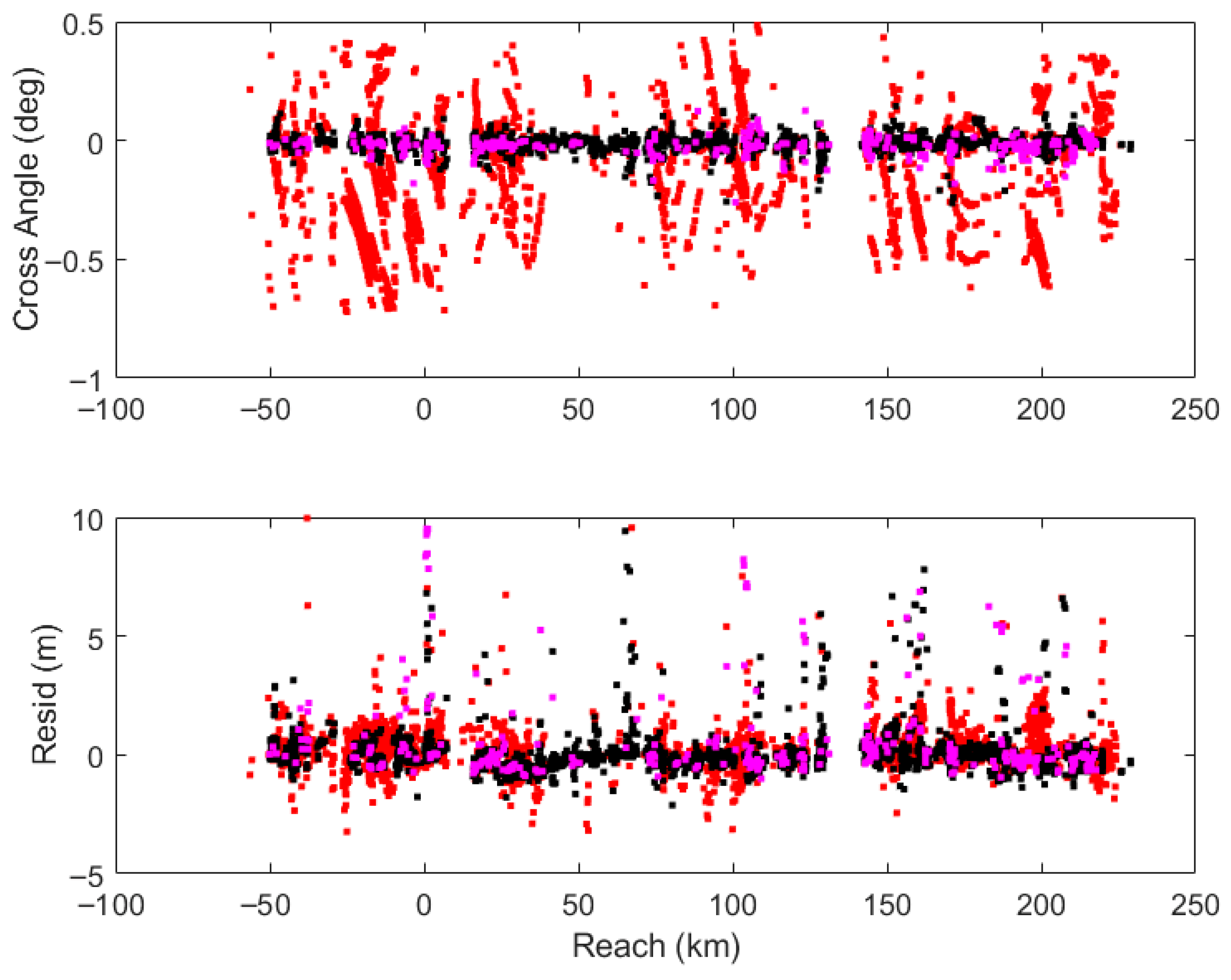

3.2. SARin Cross-Angle over Amazon near Tabatinga

4. Results

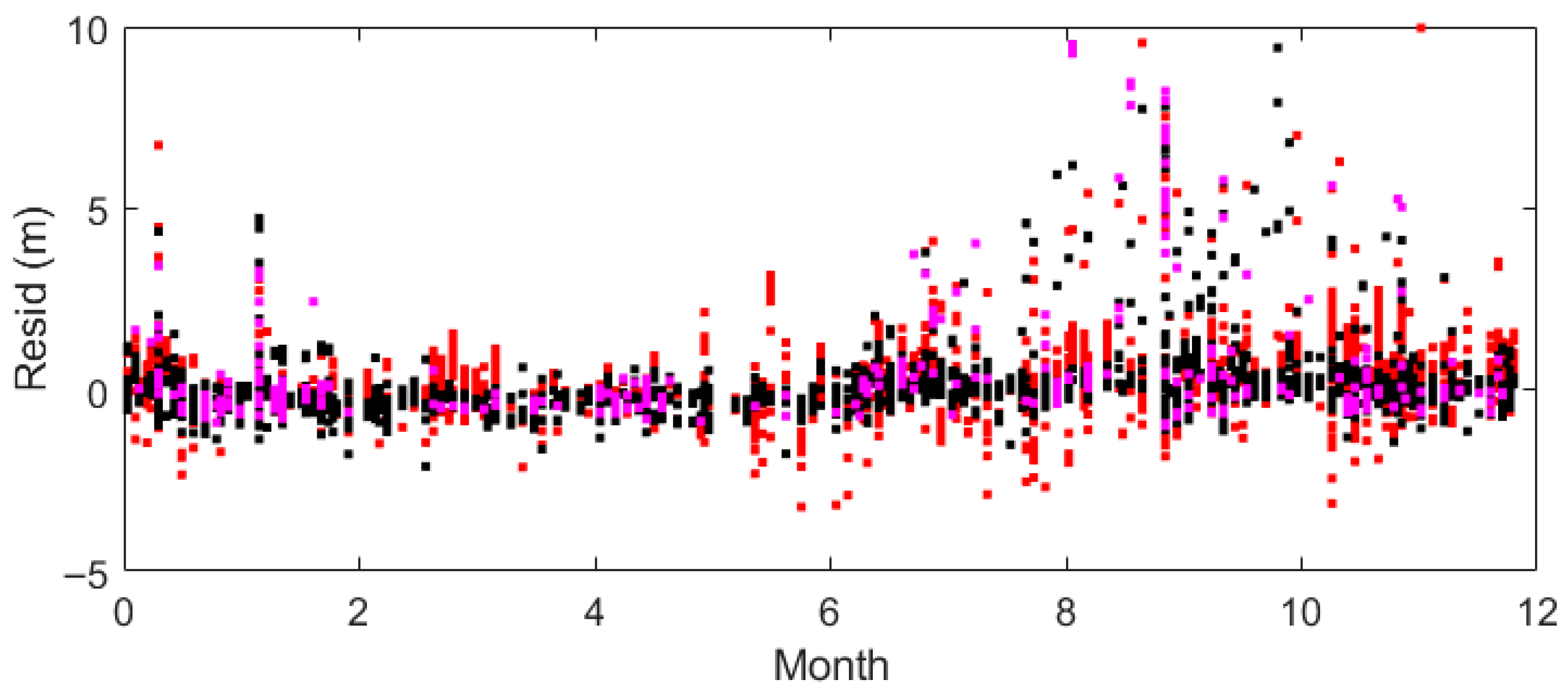

4.1. River Height

4.2. River Slope and Velocity

4.3. Roll Angle and Sigma Nought

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FBR | Full Bit Rate |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| GDR | Geophysical Data Record |

| HPF | High |

| L1A | Level 1A |

| LRM | Low Resolution Mode |

| OGOG | Offset Centre of Gravity |

| POCA | Point of Closest Approach |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SARin | Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Birkett, C.M. The contribution of TOPEX/POSEIDON to the global monitoring of climatically sensitive lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1995, 100, 25179–25204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.A.M.; Garlick, J.D.; Freeman, J.A.; Mathers, E.L. Global inland water monitoring from multi-mission altimetry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L16401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, S.J.; O’Donnell, G.M.; Moore, P.; Kilsby, C.G.; Fowler, H.J.; Berry, P.A.M. Using satellite altimetry data to augment flow estimation techniques on the Mekong River. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 3811–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwatke, C.; Dettmering, D.; Börgens, E.; Bosch, W. Potential of SARAL/AltiKa for inland water applications. Mar. Geod. 2015, 38, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, C.M.M.; Jiang, L.; Tøttrup, C.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Sentinel-3 radar altimetry for river monitoring—A catchment-scale evaluation of satellite water surface elevation from Sentinel-3A and Sentinel-3B. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlon, C.J.; Cullen, R.; Giulicchi, L.; Vuilleumier, P.; Francis, C.R.; Kuschnerus, M.; Simpson, W.; Bouridah, A.; Caleno, M.; Bertoni, R.; et al. The Copernicus Sentinel-6 mission: Enhanced continuity of satellite sea level measurements from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, H.; Andersen, O.B.; Stenseng, L.; Nielsen, K.; Knudsen, P. CryoSat-2 altimetry for river level monitoring—Evaluation in the Ganges–Brahmaputra River basin. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 168, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.; Godiksen, P.N.; Villadsen, H.; Madsen, H.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Application of CryoSat-2 altimetry data for river analysis and modelling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.; Birkinshaw, S.J.; Ambrózio, A.; Restano, M.; Benveniste, J. CryoSat-2 Full Bit Rate Level 1A processing and validation for inland water applications. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 62, 1497–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Makhoul, E.; Escorihuela, M.J.; Zribi, M.; Seguí, P.Q.; García, P.; Roca, M. Analysis of Retrackers’ Performances and Water Level Retrieval over the Ebro River Basin Using Sentinel-3. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Nielsen, K.; Andersen, O.B.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. A bigger picture of how the Tibetan lakes have changed over the past decade revealed by CryoSat-2 altimetry. J. Geophy. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2020JD033161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinherenbrink, M.; Naeije, M.; Slobbe, C.; Egido, A.; Smith, W. The performance of CryoSat-2 ful-ly-focussed SAR for inland water-level estimation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, S.; Sneeuw, N.; Benveniste, J.; Dinardo, S.; Issawy, E.; Zhang, G. Evaluation of CryoSat-2 water level derived from different retracking scenarios over selected inland water bodies. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 947–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossieris, S.; Tsiakos, V.; Tsimiklis, G.; Amditis, A. Inland Water Level Monitoring from Satellite Observations: A Scoping Review of Current Advances and Future Opportunities. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lee, H.; Shum, C.K.; Alsdorf, D.; Schwartz, F.; Tseng, K.-H.; Yi, Y.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Tseng, H.-Z.; Braun, A.; et al. Application of retracked satellite altimetry for inland hydrologic studies. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 3913–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-Y.; Kao, H.-C. Retracked Jason-2 altimetry over small water bodies: Case study of Bajhang River, Taiwan. Mar. Geod. 2011, 34, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Moore, P.; Li, Z.; Li, F. Lake Level Change From Satellite Altimetry Over Seasonally Ice-Covered Lakes in the Mackenzie River Basin. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 8143–8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, H.; Deng, X.; Andersen, O.B.; Stenseng, L.; Nielsen, K.; Knudsen, P. Improved inland water levels from SAR altimetry using novel empirical and physical retrackers. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; An, Z.; Xue, H.; Yao, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z. INPPTR: An improved retracking algorithm for inland water levels estimation using Cryosat-2 SARin data. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boergens, E.; Dettmering, D.; Schwatke, C.; Seitz, F. Water level, areal extent and volume change of Lake Tanganyika, Lake Turkana, Lake Tonle Sap and Lake Constance: Multi-year time series from satellite altimetry and remote sensing [dataset publication series]. PANGAEA 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.; Moore, P.; Edwards, S. GNSS assessment of sentinel-3A ECMWF tropospheric delays over inland waters. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 2827–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappart, F.; Calmant, S.; Cauhope, M.; Seyler, F.; Cazenave, A. Preliminary Results of ENVISAT RA-2-Derived Water Levels Validation over the Amazon Basin. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 100, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.S.; Seyler, F.; Calmant, S.; Filho, O.C.R.; Roux, E.; Araújo, A.A.M.; Guyot, J.L. Water level dynamics of Amazon wetlands at the watershed scale by satellite altimetry. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 33, 3323–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calmant, S.; Seyler, F.; Cretaux, J.F. Monitoring continental surface waters by satellite altimetry. Surv. Geophys. 2008, 29, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.S.; Calmant, S.; Seyler, F.; Filho, O.C.R.; Cochonneau, G.; Mansur, W.J. Water levels in the Amazon basin derived from the ERS 2 and ENVISAT radar altimetry missions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2160–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, P.; Bercher, N.; Calmant, S. New processing approaches on the retrieval of water levels in EN-VISAT and SARAL radar altimetry over rivers: A case study of the São Francisco River, Brazil. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 156, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappart, F.; Papa, F.; Marieu, V.; Malbeteau, Y.; Jordy, F.; Calmant, S.; Durand, F.; Bala, S. Preliminary assessment of SARAL/AltiKa observations over the Ganges-Brahmaputra and Irrawaddy Rivers. Mar. Geod. 2015, 38, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boergens, E.; Dettmering, D.; Schwatke, C.; Seitz, F. Treating the Hooking Effect in Satellite Altimetry Data: A Case Study along the Mekong River and Its Tributaries. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingham, D.; Francis, C.; Baker, S.; Bouzinac, C.; Brockley, D.; Cullen, R.; de Chateau-Thierry, P.; Laxon, S.; Mallow, U.; Mavrocordatos, C.; et al. CryoSat: A mission to determine the fluctuations in Earth’s land and marine ice fields. Adv. Space Res. 2005, 37, 841–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinherenbrink, M.; Ditmar, P.; Lindenbergh, R. Retracking Cryosat data in the SARIn mode and robust lake level extraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 152, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gommenginger, C.; Thibaut, P.; Fenoglio-Marc, L.; Quartly, G.; Deng, X.; Gomez-Enri, J.; Challenor, P.; Gao, Y. Retracking altimeter waveforms near the coasts. A review of retracking methods and some applications to coastal waveforms. In Coastal Altimetry; Vignudelli, S., Kostianoy, A.G., Cipollini, P., Benveniste, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 61–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Edward, J.W.; MacArthur, J.L. Pulse Compression and Sea Level Tracking in Satellite Al-timetry. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1989, 6, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Latrubesse, E.M. Modeling suspended sediment distribution patterns of the Amazon River using MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 147, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.-F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Shen, P.; Guan, X.; Liu, X.; Massari, C.; Wang, Z.; Feng, M.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; et al. Regional-scale intelligent optimization and topography impact in restoring global precipitation data gaps. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávarri, E.; Crave, A.; Bonnet, M.-P.; Mejía, A.; Da Silva, J.S.; Guyot, J.L. Hydrodynamic modelling of the Amazon River: Factors of uncertainty. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2013, 44, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.d.S.; Blanco, C.J.C.; Junior, A.C.P.B. Flow-velocity model for hydrokinetic energy availability assessment in the Amazon. Acta Sci. Technol. 2019, 42, e45703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFavour, G.; Alsdorf, D. Water slope and discharge in the Amazon River estimated using the shuttle radar topography mission digital elevation model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | Mask | Min/Max Gauge (km) | Nmax | Nused | Offset Δ (m) | Slope (m/km) | Velocity V (m/s) | δθr (deg) | RMSE (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No corr | 1# | −50.2/229.1 | 3415 | 3153 | 57.435 ± 0.008 | 0.03513 ± 0.00010 | 1.7909 ± 0.0007 | 0.423 | ||

| i_3 | 1# | −50.2/229.1 | 3415 | 3215 | 57.498 ± 0.007 | 0.03504 ± 0.00009 | 1.7920 ± 0.0006 | 0.408 | ||

| i_4 | 1# | −50.2/229.1 | 3415 | 3208 | 57.507 ± 0.007 | 0.03508 ± 0.00009 | 1.7962 ± 0.0006 | −0.0036 ± 0.0078 | 0.404 | |

| ii_3 | #1 | −56.3/229.1 | 5529 | 5232 | 57.555 ± 0.007 | 0.03502 ± 0.00009 | 1.8242 ± 0.0013 | 0.524 | ||

| ii_4 | #1 | −56.3/229.1 | 5529 | 5258 | 57.586 ± 0.008 | 0.03504 ± 0.00009 | 1.8132 ± 0.0013 | −0.0033 ± 0.0018 | 0.527 | |

| ii_5 | #1 | −56.3/229.1 | 5529 | 5256 | 57.589 ± 0.008 | 0.03507 ± 0.00009 | 1.8209 ± 0.0007 | −0.0030 ± 0.0024 | 0.0004 ± 0.0001 | 0.525 |

| iii_3 | 11 | −50.2/229.1 | 3122 | 2981 | 57.497 ± 0.008 | 0.03504 ± 0.00010 | 1.7932 ± 0.0006 | 0.408 | ||

| iii_4 | 11 | −50.2/229.1 | 3122 | 2976 | 57.505 ± 0.008 | 0.03508 ± 0.00010 | 1.7965 ± 0.0006 | −0.0031 ± 0.0089 | 0.404 | |

| iv_3 | 01 | −56.3/225.7 | 2397 | 2286 | 57.613 ± 0.014 | 0.03485 ± 0.00016 | 1.9028 ± 0.0030 | 0.683 | ||

| iv_4 | 01 | −56.3/225.7 | 2397 | 2301 | 57.703 ± 0.015 | 0.03483 ± 0.00016 | 1.8862 ± 0.0018 | −0.0040 ± 0.0018 | 0.664 | |

| iv_5 | 01 | −56.3/225.7 | 2397 | 2304 | 57.735 ± 0.016 | 0.03484 ± 0.00016 | 1.8898 ± 0.0018 | −0.0029 ± 0.0030 | 0.0013 ± 0.0002 | 0.664 |

| No corr | 1# | 84.2/204.9 | 1598 | 1465 | 57.383 ± 0.011 | 0.03446 ± 0.00031 | 1.7756 ± 0.0007 | 0.415 | ||

| v_3 | 1# | 84.2/204.9 | 1598 | 1483 | 57.471 ± 0.010 | 0.03461 ± 0.00027 | 1.7780 ± 0.0006 | 0.371 | ||

| v_4 | 1# | 84.2/204.9 | 1598 | 1483 | 57.480 ± 0.010 | 0.03462 ± 0.00027 | 1.7821 ± 0.0006 | −0.0028 ± 0.0091 | 0.370 | |

| vi_3 | #1 | 84.7/204.5 | 2410 | 2293 | 57.240 ± 0.010` | 0.03250 ± 0.00027 | 1.7556 ± 0.0008 | 0.476 | ||

| vi_4 | #1 | 84.7/204.5 | 2410 | 2285 | 57.246 ± 0.010 | 0.03258 ± 0.00028 | 1.7608 ± 0.0007 | 0.0009 ± 0.0003 | 0.46.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moore, P.; Pearson, C. Phase Shift Analysis of Cryosat-2 SARin Waveforms: Inland Water Off-Pointing Corrections. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213627

Moore P, Pearson C. Phase Shift Analysis of Cryosat-2 SARin Waveforms: Inland Water Off-Pointing Corrections. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(21):3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213627

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoore, Philip, and Christopher Pearson. 2025. "Phase Shift Analysis of Cryosat-2 SARin Waveforms: Inland Water Off-Pointing Corrections" Remote Sensing 17, no. 21: 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213627

APA StyleMoore, P., & Pearson, C. (2025). Phase Shift Analysis of Cryosat-2 SARin Waveforms: Inland Water Off-Pointing Corrections. Remote Sensing, 17(21), 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213627