Machine Learning-Based Sea Surface Wind Speed Retrieval from Dual-Polarized Sentinel-1 SAR During Tropical Cyclones

Highlights

- Machine learning models for TC wind speed retrieval are proposed using dual-polarized S-1 SAR data after noise removal, which can reduce the impact of additive and multiplicative noise on cross-polarized data.

- The variable of SST was introduced in the proposed machine learning model for C-band SAR data and improved wind speed inversion results under TC conditions.

- The approach of fusing advanced signal processing (noise removal) with machine learning models that incorporate relevant geophysical variables can be extended to other satellite sensors and to retrieving other oceanic or atmospheric parameters.

- SST is a critical physical variable in the TC wind retrieval process that has been previously underutilized or overlooked in C-band SAR models.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Machine learning models for TC wind speed retrieval are proposed using dual-polarized S-1 SAR data after noise removal to reduce the impact of additive and multiplicative noise on cross-polarized data.

- (2)

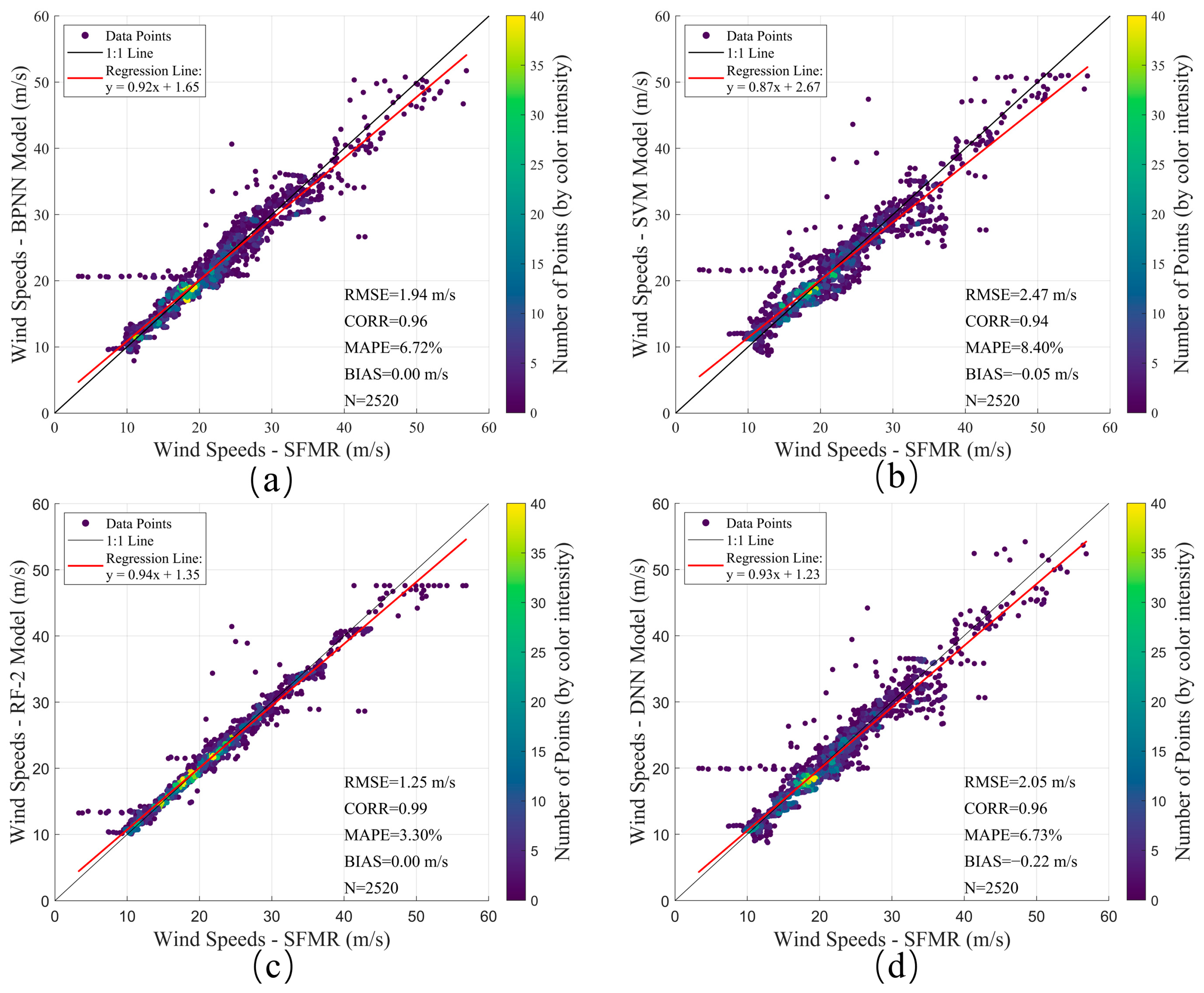

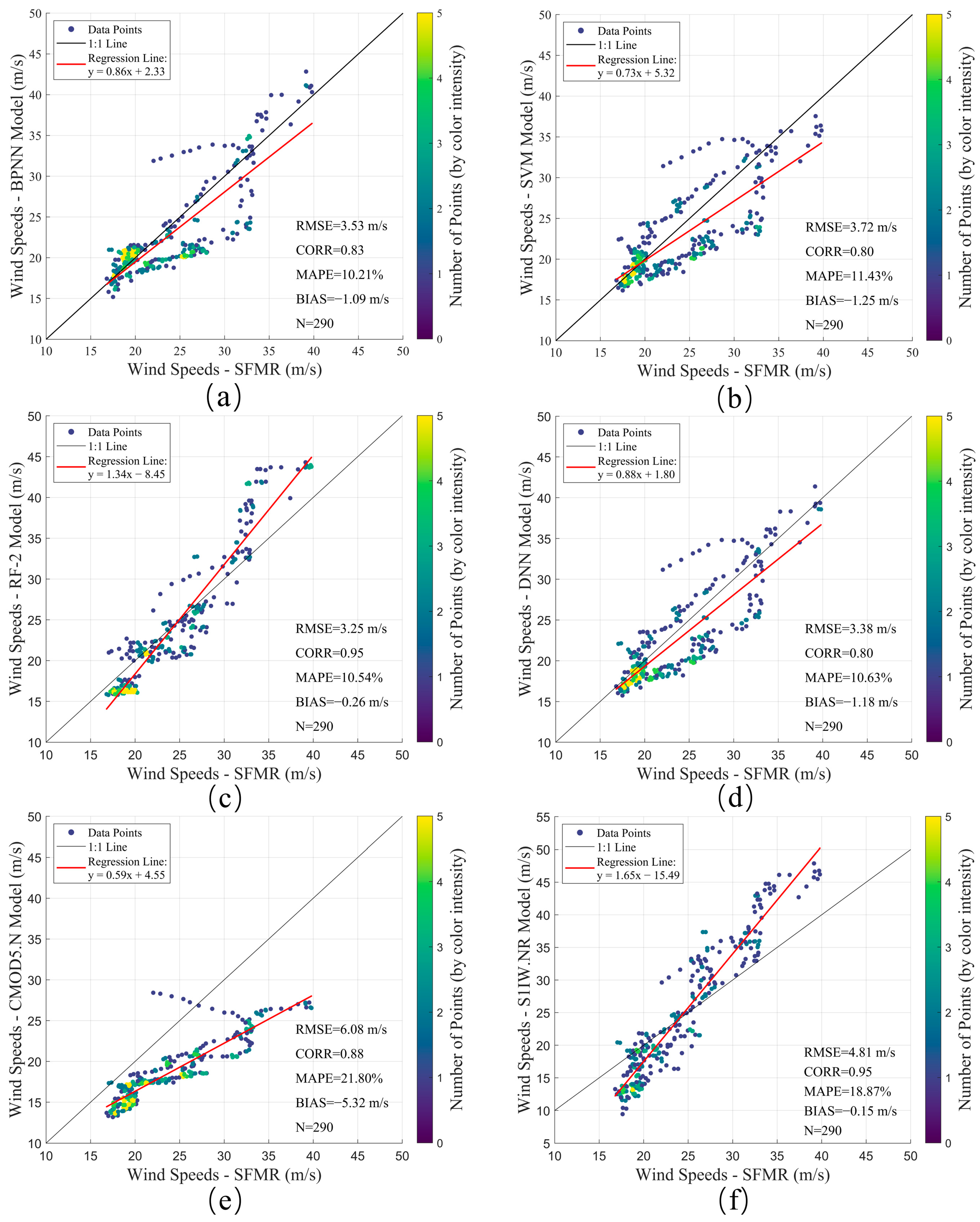

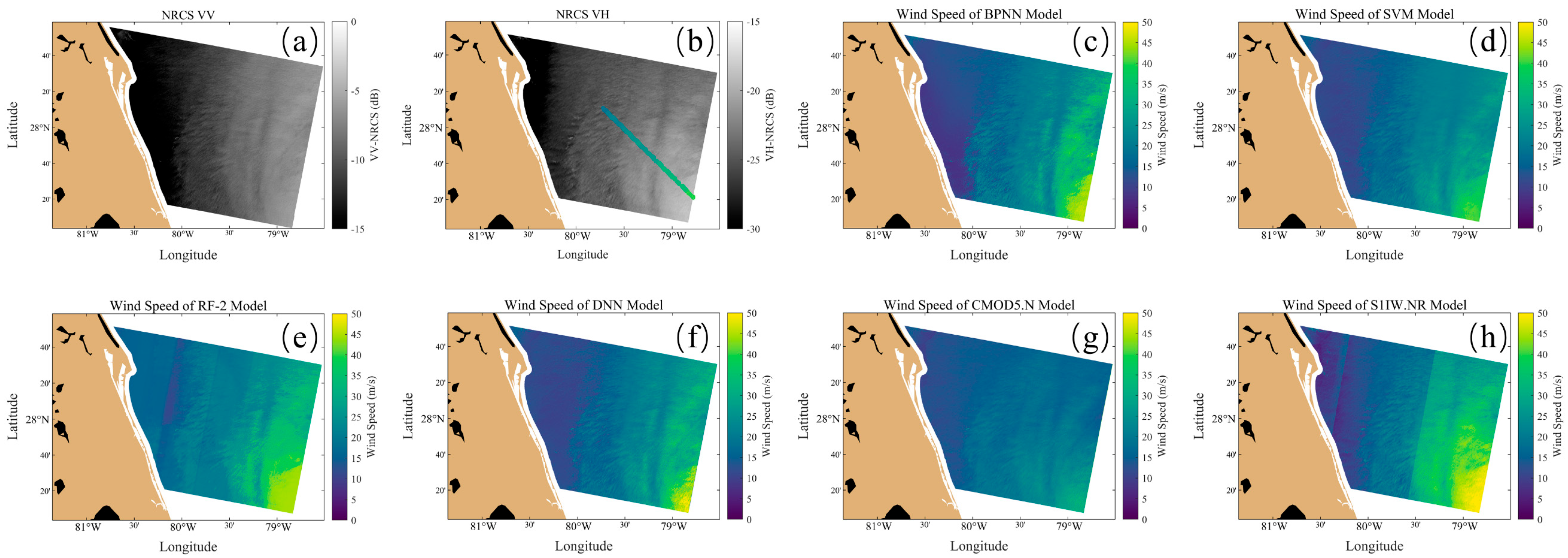

- Different SSW model results during TCs based on traditional GMFs (CMOD5.N and S1IW.NR) and machine learning methods (BPNN, RF, SVM, and DNN) are compared, whose results show that the RF model has a better performance.

- (3)

- The variable of SST was introduced in the proposed RF model, which can improve SSW inversion results under high wind conditions.

2. Datasets

2.1. Data Sets

2.1.1. S-1 SAR Data

2.1.2. SFMR Measurements

2.2. Data Pre-Processing

3. Wind Speed Inversion Model

3.1. The CMOD5.N Model

3.2. The S1IW.NR Model

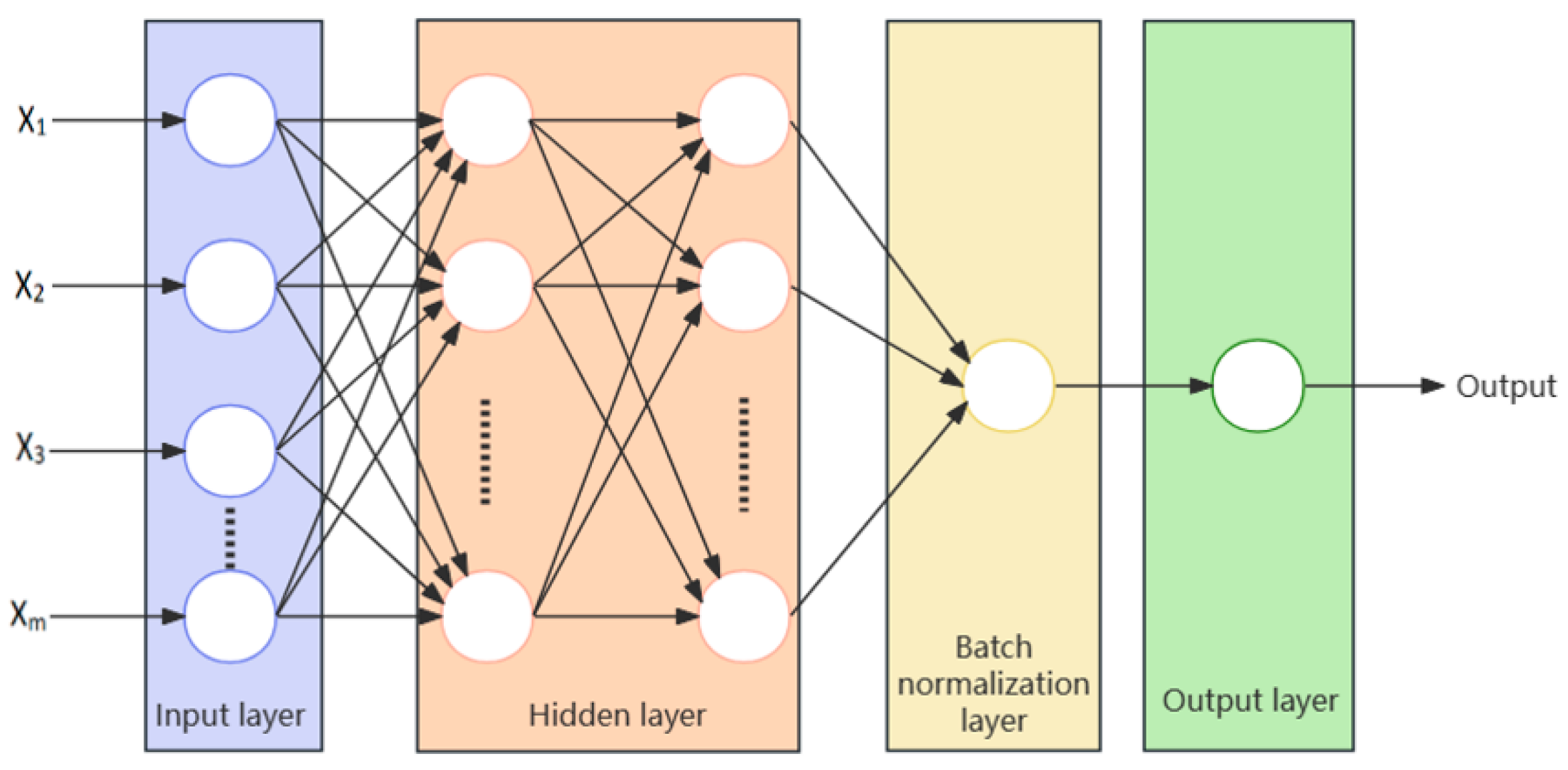

3.3. The BPNN Model

3.4. The SVM Model

3.5. The RF Model

3.6. The DNN Method

4. Results

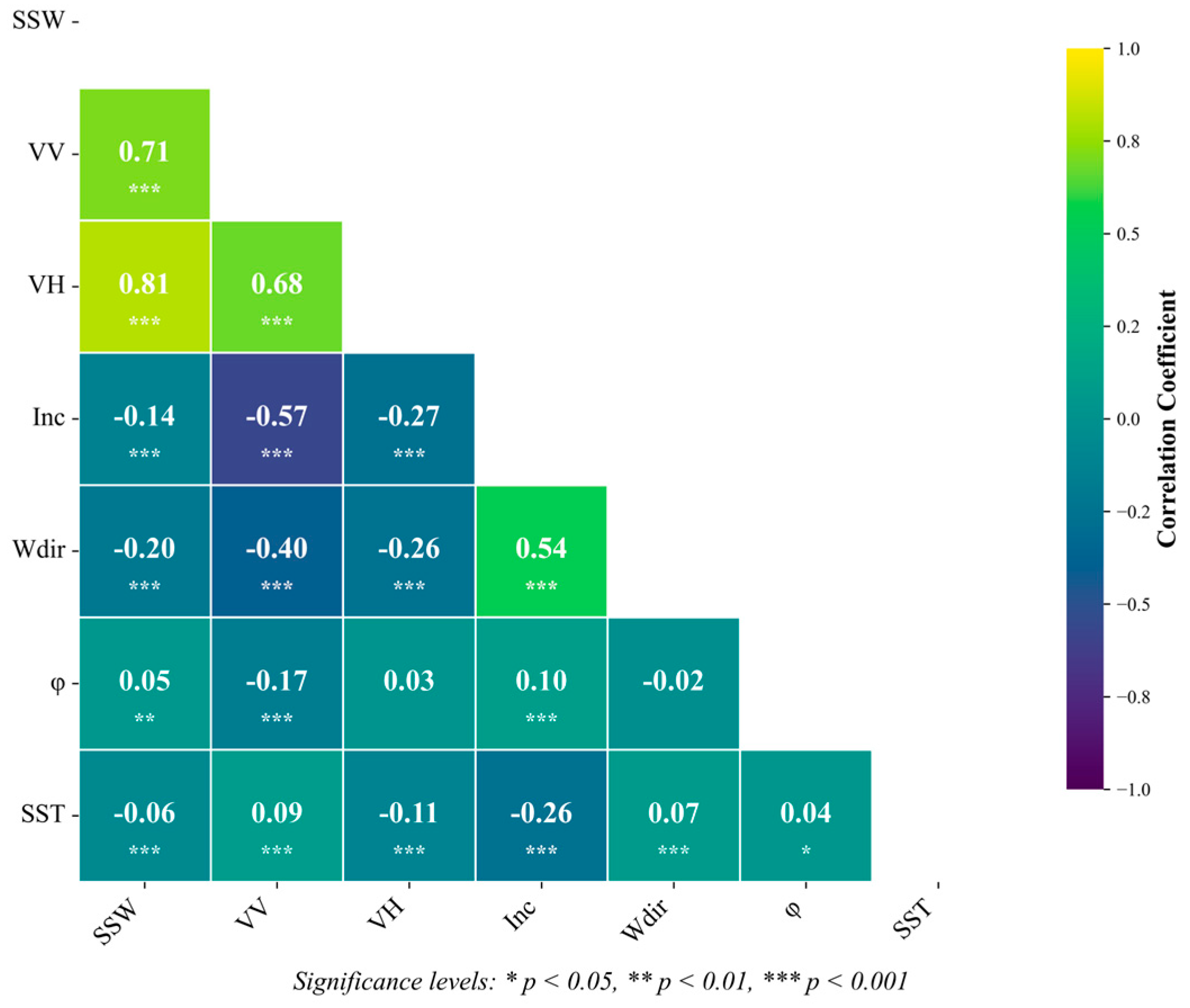

4.1. Correlation Analysis and Selection of Model Parameters

4.2. Inversion Results Based on Dual-Polarized SAR Data and Conventional Model Parameters

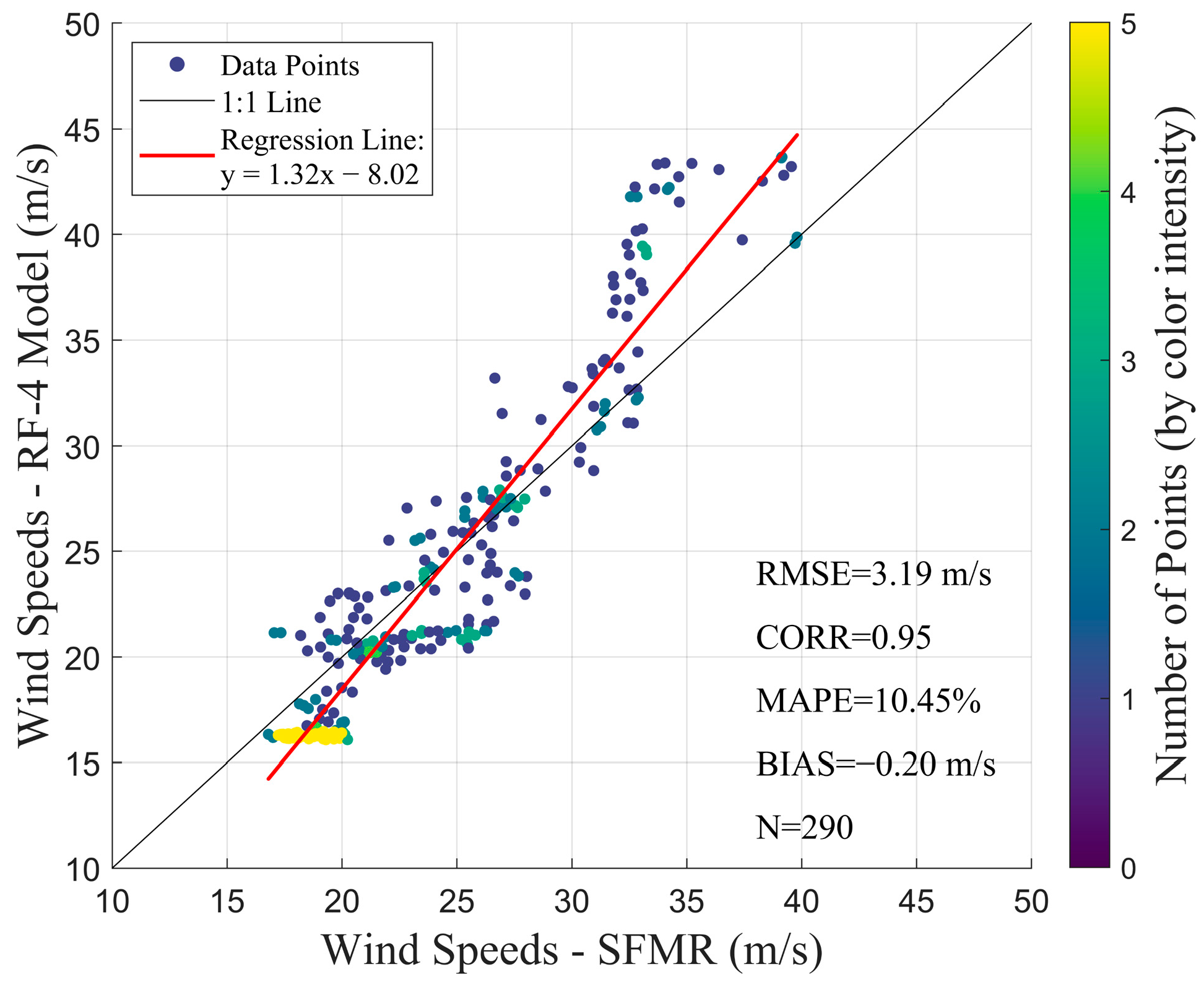

4.3. Verification and Analysis of TCs Cases Based on RF Models

4.4. Performance of Different Models on High SSWs

5. Discussion

5.1. Effect of SST on the Retrieved Model

5.2. Effect of Rainfall Rate on Retrieved Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, P.; Johannessen, J.A.; Yan, X.-H.; Geng, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhu, L. A Study of the Intensity of Tropical Cyclone Idai Using Dual-Polarization Sentinel-1 Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, R.; Heft-Neal, S.; Chavas, D.R.; Griswold, M.; Wang, Z.; Clark-Ginsberg, A.; Guha-Sapir, D.; Bendavid, E.; Wagner, Z. Global Population Profile of Tropical Cyclone Exposure from 2002 to 2019. Nature 2023, 626, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, T.W. Structure of the Surface Wind Field from the Seasat SAR. J. Geophys. Res. 1986, 91, 2308–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempreviva, A.M.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Pryor, S.C. Review of Methodologies for Offshore Wind Resource Assessment in European Seas. Surv. Geophys. 2008, 29, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubrawa, P.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Pryor, S.C.; Hasager, C.B.; Badger, M.; Karagali, I. Satellite Winds as a Tool for Offshore Wind Resource Assessment: The Great Lakes Wind Atlas. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 168, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Guo, S.; Li, L.; Qu, X.; Dai, Y. Data Quality Evaluation of Sentinel-1 and GF-3 SAR for Wind Field Inversion. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A.; Anderson, D. Scatterometer Data Interpretation: Estimation and Validation of the Transfer Function CMOD4. J. Geophys. Res. 1997, 102, 5767–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Stoffelen, A.; De Haan, S. An Improved C-Band Scatterometer Ocean Geophysical Model Function: CMOD5. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, C03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H. Comparison of C-Band Scatterometer CMOD5.N Equivalent Neutral Winds with ECMWF. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2010, 27, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A.; Verspeek, J.A.; Vogelzang, J.; Verhoef, A. The CMOD7 Geophysical Model Function for ASCAT and ERS Wind Retrievals. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Elfouhaily, T.; Chapron, B. Polarization Ratio for Microwave Backscattering from the Ocean Surface at Low to Moderate Incidence Angles. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Seattle, WA, USA, 6–10 July 1998; pp. 1671–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Mouche, A.A.; Hauser, D.; Daloze, J.F.; Guerin, C. Dual-Polarization Measurements at C-Band over the Ocean: Results from Airborne Radar Observations and Comparison with ENVISAT ASAR Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelan, M.A.; Haus, B.K.; Reul, N.; Plant, W.J.; Stiassnie, M.; Graber, H.C.; Brown, O.B.; Saltzman, E.S. On the Limiting Aerodynamic Roughness of the Ocean in Very Strong Winds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L18306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Perrie, W. Cross-Polarized Synthetic Aperture Radar: A New Potential Measurement Technique for Hurricanes. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.A.; Stoffelen, A.; van Zadelhoff, G.; Perrie, W.; Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Shen, H. Cross-Polarization Geophysical Model Function for C-Band Radar Backscattering from the Ocean Surface and Wind Speed Retrieval. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Perrie, W.; Hwang, P.A.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X. A Hurricane Wind Speed Retrieval Model for C-Band RADARSAT-2 Cross-Polarization ScanSAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 4766–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, X.M.; Feng, Q.; Ren, Y.; Shi, Y. Retrieval of Sea Surface Wind Speeds from Gaofen-3 Full Polarimetric Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Guan, C. Extreme Wind Speeds Retrieval Using Sentinel-1 IW Mode SAR Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, J.; Falchetti, S.; Wackerman, C.; Maresca, S.; Caruso, M.J.; Graber, H.C. Tropical Cyclone Winds Retrieved from C-Band Cross-Polarized Synthetic Aperture Radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 2887–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.M. Denoising Sentinel-1 Extra-Wide Mode Cross-Polarization Images Over Sea Ice. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 2116–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Won, J.S.; Korosov, A.A.; Babiker, M.; Miranda, N. Textural Noise Correction for Sentinel-1 TOPSAR Cross-Polarization Channel Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4040–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lin, M.; Zheng, Q.; Yuan, X.; Liang, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J. A Typhoon Wind-Field Retrieval Method for the Dual-Polarization SAR Imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1511–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portabella, M.; Stoffelen, A.; Johannessen, J.A. Toward an Optimal Inversion Method for Synthetic Aperture Radar Wind Retrieval. J. Geophys. Res. 2002, 107, C08011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, F.; Chen, G.; Yu, W. A Damped Newton Variational Inversion Method for SAR Wind Retrieval. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouche, A.A.; Chapron, B.; Zhang, B.; Husson, R. Combined Co- and Cross-Polarized SAR Measurements Under Extreme Wind Conditions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 6746–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouche, A.; Chapron, B.; Knaff, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Combot, C. Copolarized and Cross-Polarized SAR Measurements for High-Resolution Description of Major Hurricane Wind Structures: Application to Irma Category 5 Hurricane. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 3905–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. A New Approach for Ocean Surface Wind Speed Retrieval Using Sentinel-1 Dual-Polarized Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, S.; Ouyang, C.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Geoscience: Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Innovation 2024, 5, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, J.; Schiller, H.; Schulz-Stellenfleth, J.; Lehner, S. Global Wind Speed Retrieval from SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Jia, T.; Feng, Q.; Li, X. Sea Surface Wind Speed Retrieval from Sentinel-1 HH Polarization Data Using Conventional and Neural Network Methods. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2021, 40, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Li, X.; Wang, H. The Fusion of Physical, Textural, and Morphological Information in SAR Imagery for Hurricane Wind Speed Retrieval Based on Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4207513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Xu, W.; Zhong, X.; Johannessen, J.A.; Yan, X.-H.; Geng, X.; He, Y.; Lu, W. A Neural Network Method for Retrieving Sea Surface Wind Speed for C-Band SAR. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shao, W.; Shen, W.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, X. Machine Learning Applied to a Dual-Polarized Sentinel-1 Image for Wind Retrieval of Tropical Cyclones. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Shirooka, R.; Yoshizaki, M.; Takayabu, Y.N. Meridional SST Gradient in The Western North Pacific Warm Pool Associated with Typhoon Generation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Colon, P.; Yan, X.-H. Observations of East Coast Upwelling Conditions in Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1999, 37, 2239–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-S.; Park, K.-A.; Li, X.; Mouche, A.A.; Chapron, B.; Lee, M. Observation of Wind Direction Change on the Sea Surface Temperature Front Using High-Resolution Full Polarimetric SAR Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 2599–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Q.; Perrie, W.; Kudryavtsev, V.; He, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhang, B.; Hu, H. Radar Imaging of Intense Nonlinear Ekman Divergence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 9810–9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentamy, A.; Grodsky, S.A.; Carton, J.A.; Croize-Fillon, D.; Chapron, B. Matching ASCAT and QuikSCAT Winds. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2012, 117, C02011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodsky, S.A.; Kudryavtsev, V.N.; Bentamy, A.; Carton, J.A.; Chapron, B. Does Direct Impact of SST on Short Wind Waves Matter for Scatterometry? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Stoffelen, A.; Zhao, C.; Vogelzang, J.; Verhoef, A.; Verspeek, J. An SST-Dependent Ku-Band Geophysical Model Function for RapidScat. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 3461–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlhorn, E.W.; Black, P.G.; Franklin, J.L.; Goodberlet, M.; Carswell, J.; Goldstein, A.S. Hurricane Surface Wind Measurements. from an Operational Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer. Mon. Weather Rev. 2007, 135, 3070–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, B.W.; Uhlhorn, E.W. Improved Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer Tropical Cyclone Surface Winds in Heavy Precipitation. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2014, 31, 2392–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Guo, Q.; Chen, Y.; Mansaray, L.R.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Spatial Scale Effect on Wind Speed Retrieval Accuracy Using Sentinel-1 Copolarization SAR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yuen, K.V.; Yang, X.F.; Zhang, B. A Nonparametric Tropical Cyclone Wind Speed Estimation Model Based on Dual-Polarization SAR Observations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4208213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.G.; Wang, Q.; Feng, J.; He, L.; Li, R.; Lu, W.; Liao, E.; Lai, Z. Can Three-Dimensional Nitrate Structure Be Reconstructed from Surface Information with Artificial Intelligence?—A Proof-of-Concept Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Su, H.; Yang, X.; Yan, X.-H. Subsurface Temperature Estimation from Remote Sensing Data Using a Clustering-Neural Network Method. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 229, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Tan, S.; Ma, W.; Li, Z.; Li, X. Effects of Temperature on Sea Surface Radar Backscattering Under Neutral and Nonneutral Atmospheric Conditions for Wind Retrieval Applications: A Numerical Study. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 2727–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, Y. Impact of Ships and Ocean Fronts on Coastal Sea Surface Wind Measurements From the Advanced Scatterometer. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 2162–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpers, W.; Zhang, B.; Mouche, A.A.; Zeng, K.; Chan, P.K. Rain Footprints on C-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar Images of the Ocean—Revisited. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 187, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ai, W.; Zhang, X.; Guan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, S. Correction of Sea Surface Wind Speed Based on SAR Rainfall Grade Classification Using Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mouche, A.A.; Perrie, W. First Quasi-Synchronous Hurricane Quad-Polarization Observations by C-Band Radar Constellation Mission and RADARSAT-2. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4206510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcione, V.; Grieco, G.; Portabella, M.; Nunziata, F.; Migliaccio, M. A Novel Azimuth Cutoff Implementation to Retrieve Sea Surface Wind Speed From SAR Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 3331–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, G.; Lin, W.; Migliaccio, M.; Nirchio, F.; Portabella, M. Dependency of the Sentinel-1 azimuth wavelength cut-off on significant wave height and wind speed. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 5086–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TC Name | Time | Satellites | Mode | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darby | 22 July 2016 15:59 | S1A | IW | 1 |

| Darby | 23 July 2016 04:30 | S1A | IW | 1 |

| Franklin | 9 August 2017 12:01 | S1A | IW | 1 |

| Florence | 13 September 2018 23:12 | S1B | IW | 1 |

| Florence | 14 September 2018 11:15 | S1B | IW | 1 |

| Micheal | 8 October 2018 23:50 | S1B | EW | 1 |

| Dorian | 27 August 2019 22:19 | S1A | IW | 1 |

| Dorian | 29 August 2019 10:21 | S1B | IW | 1 |

| Dorian | 30 August 2019 22:46 | S1A | IW | 1 |

| Dorian | 31 August 2019 10:53 | S1A | IW | 2 |

| Dorian | 3 September 2019 11:17 | S1A | IW | 2 |

| Dorian | 4 September 2019 11:07 | S1B | IW | 2 |

| Dorian | 13 September 2019 11:08 | S1B | IW | 2 |

| Isais | 2 August 2020 23:20 | S1B | IW | 1 |

| Delta | 8 October 2020 00:07 | S1B | IW | 1 |

| Delta | 8 October 2020 00:08 | S1B | IW | 1 |

| Delta | 9 October 2020 12:07 | S1A | IW | 2 |

| Zeta | 28 October 2020 11:59 | S1A | IW | 2 |

| Eta | 10 November 2020 23:35 | S1A | IW | 1 |

| Category | Hyperparameter | BPNN | SVM | DNN | RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Structure | Number of hidden layers | 2 | - | 3 | - |

| Neurons per hidden layer | (3, 3) | - | (19, 18, 1) | - | |

| Neural Network Training | Epochs | 500 | - | 100 | - |

| Learning rate | 0.02 | - | 0.001 | - | |

| SVM Kernel Settings | Kernel | - | Gaussian (RBF) | - | - |

| Gamma (Kernel Coefficient) | - | 4.4 | - | - | |

| Random Forest Settings | Number of Trees (n_estimators) | - | - | - | 100 |

| Bootstrap Sampling | - | - | - | True | |

| Max Sample Ratio | - | - | - | 0.8 | |

| Min Samples per Leaf | - | - | - | 7 |

| Training Set | Validation Set | Test Set | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (m/s) | MAPE | CORR | Bias (m/s) | RMSE (m/s) | MAPE | CORR | Bias (m/s) | RMSE (m/s) | MAPE | CORR | Bias (m/s) | |

| RF-1 (σVV, σVH, Inc, and Wdir) | 1.40 | 3.79 | 0.98 | 0 | 1.00 | 3.36 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 3.40 | 10.63 | 0.94 | −0.53 |

| RF-2 (σVV, σVH, Inc, and φ) | 1.25 | 3.30 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.78 | 2.76 | 0.99 | −0.02 | 3.25 | 10.54 | 0.95 | −0.26 |

| RF-3 (σVV, σVH, Inc, φ, and SST) | 0.93 | 2.07 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.50 | 1.81 | 0.99 | −0.01 | 2.41 | 8.60 | 0.95 | −0.39 |

| RMSE (m/s) | MAPE (%) | CORR | Bias (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPNN | 6.21 | 14.00 | 0.33 | 2.34 |

| SVM | 5.50 | 13.65 | 0.76 | 4.03 |

| RF-2 | 2.28 | 3.52 | 0.93 | −0.93 |

| RF-3 | 1.74 | 2.26 | 0.96 | −0.58 |

| DNN | 5.11 | 12.59 | 0.72 | 3.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, P.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Suo, L.; Xue, S.; Zhong, X. Machine Learning-Based Sea Surface Wind Speed Retrieval from Dual-Polarized Sentinel-1 SAR During Tropical Cyclones. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213626

Yu P, Lin Y, Zhou Y, Suo L, Xue S, Zhong X. Machine Learning-Based Sea Surface Wind Speed Retrieval from Dual-Polarized Sentinel-1 SAR During Tropical Cyclones. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(21):3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213626

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Peng, Yanyan Lin, Yunxuan Zhou, Lingling Suo, Sihan Xue, and Xiaojing Zhong. 2025. "Machine Learning-Based Sea Surface Wind Speed Retrieval from Dual-Polarized Sentinel-1 SAR During Tropical Cyclones" Remote Sensing 17, no. 21: 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213626

APA StyleYu, P., Lin, Y., Zhou, Y., Suo, L., Xue, S., & Zhong, X. (2025). Machine Learning-Based Sea Surface Wind Speed Retrieval from Dual-Polarized Sentinel-1 SAR During Tropical Cyclones. Remote Sensing, 17(21), 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17213626